Abstract

Motor competence and self-regulation develop rapidly in early childhood; emerging work suggests motor competence interventions as a promising way to promote self-regulation (e.g., behavioral inhibition; cognitive flexibility) in young children. We tested the impact of a mastery-focused motor competence intervention (Children’s Health Activity Motor Program [CHAMP])1 on behavioral and cognitive aspects of self-regulation among children attending Head Start. Grounded in Achievement Goal Theory, CHAMP encourages children’s autonomy to navigate a mastery-oriented motor skill learning environment. Children (M age = 53.4 months, SD = 3.2) were cluster-randomized by classroom (6 per condition) to an intervention (n = 67) or control condition (n = 45). Behavioral self-regulation skills were assessed using the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders task (HTKS). Cognitive self-regulation skills were assessed using working memory and dimensional card-sorting executive function tasks. Random-effects hurdle models accounting for zero-inflated distributions indicated that children receiving CHAMP, versus not, were almost 3 times more likely to have non-zero HTKS scores at post-test; OR: 2.98 (CI 1.53, 5.81); however, there were no effects on any cognitive aspects of self-regulation (all p’s > 0.05). Mastery climate motor competence interventions are an ecologically valid strategy that may have a greater impact on preschoolers’ behavioral than cognitive aspects of self-regulation.

Keywords: behavior, cognition, early childhood, executive function, intervention, mastery climate, motor skills, self-regulation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Self-regulation (SR) is a multifaceted construct that can be defined as the ability to control cognition and behavior in service of an identified goal.2,3 SR emerges rapidly across the early childhood period (3–5 years of age) and includes distinct, yet interrelated cognitive and behavioral features.2 Cognitive SR reflects a child’s internal processing capacity and executive functioning skills such as working memory, whereas behavioral SR reflects a child’s capacity to harness such skills to intentionally control behavior and refrain from impulsive actions in the moment.2,3 Cognitive and behavioral SR skills often work together, and each has been associated with a range of early childhood outcomes, including academic achievement,4 visuomotor skills,5 and prosocial behavior.6

Early childhood is also a period of rapid development of motor competence, particularly motor skills such as running, jumping, and throwing.7 Motor competence in young children is often operationalized as motor skills or goal-directed movements that can be improved through practice and instruction. Although motor competence and SR share common fundamental processes such as the ability to plan sequenced actions, control body movements, and engage in goal-directed activity,8 motor competence is not considered central to most conceptualizations of early SR. Yet, motor competence and SR are each needed to successfully navigate early classroom settings,9 and emerging work suggests motor competence interventions may be a novel and developmentally appropriate method to promote both behavioral and cognitive SR in preschool-aged children.10,11 Indeed, exercise-based interventions in pediatric populations may improve a range of cognitive and psychosocial outcomes, including physical self-perceptions, but that the mechanisms remain unclear.12 Other evidence supports that exercise conditions that include a motor skill or motor competence element yield larger cognitive benefits than exercise conditions without skill learning.13 These cognitive benefits mirror the underlying facets of SR (e.g., working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition;3) supporting use of such interventions as potentially mechanisms to improve SR outcomes. Unfortunately, motor competence interventions have not typically evaluated both behavioral and cognitive aspects of SR, which would increase understanding of whether and how such interventions may support specific aspects of SR.

Motor competence interventions in a mastery climate, a child-centered environment that encourages independent navigation and choice in task, duration, and difficulty, are effective in improving motor outcomes14 and may be particularly important for SR. Mastery-oriented learners perceive success based on their individual effort and performance relative to their previous performance, compared to valuing external rewards; thus, a mastery-oriented learning climate increases children’s actual competence1,15 and self-perceptions of skill competence12,15 which should lead to greater engagement in skills and physical activity.15,16 The mastery-oriented learning climate is unique in that children gain and maintain skills across these interventions14,17 even with the independent navigation of the intervention session. Child behaviors during mastery-oriented learning environments remain relatively unexplored, but recent evidence supports that children only engage in appropriate motor behaviors for 36% of time during the motor skill practice portion of the intervention.17 Hence, there is unaccounted time during the intervention whereby children are not practicing motor tasks and are self-navigating interactions with peers, instructors, or managing their own emotions in an environment that is active and constantly changing. Therefore, motor interventions that use mastery-oriented learning climates may enhance SR not only through overlap of fundamental processes and neurological processing but also through the enactment of SR children must perform to successfully navigate these settings. Preliminary evidence suggests that children who engaged in mastery climate motor competence interventions maintained their SR skills assessed using a snack delay task, compared to children in control conditions who decreased in their skills, but this study did not examine impacts on cognitive aspects of SR.1 Mastery-oriented motor competence interventions may be an effective, yet overlooked approach for engaging and motivating children in activities that can improve SR. Mastery-oriented motor competence interventions may be a particularly important approach to enhance both motor competence and SR skills among children from low-income families, who often experience greater SR difficulties18 and motor delays19 compared to their middle-income peers.

1.1 |. Goal of current study

The goal of this study was to test the impact of a mastery climate motor competence intervention (Children’s Health Activity Motor Program [CHAMP])1 on aspects of behavioral and cognitive SR among preschool-aged children growing up in low-income families. We hypothesized that children who participated in CHAMP would show improved cognitive and behavioral SR. We also examined associations among indicators of cognitive and behavioral SR. Given identified maturational factors20 and sex differences21 related to SR during this developmental period, we also considered child age, child sex, and timepoint of assessment (Fall/pre-test vs. Spring/post-test) as covariates.

2 |. METHOD

2.1 |. Study design, eligibility, and recruitment

The Promoting Activity and Trajectory of Health (PATH) Study is a two-cohort, 16-week school-based, cluster-randomized controlled trial (RCT) that was completed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.22 PATH was conducted in two Head Start centers in the Midwestern United States. Head Start is a federally funded preschool program serving children from families living in poverty. The first cohort of children aged 3.5 years or older participating in PATH were eligible to participate in the current study, entitled PATH-Science of Behavior Change (PATH-SOBC).23 The purpose of PATH-SOBC was a supplemental study to assess the impact of the CHAMP intervention on behavioral and cognitive SR in young children. Exclusion criteria included medical and/or developmental conditions that would affect participation in CHAMP (information was obtained through school records).

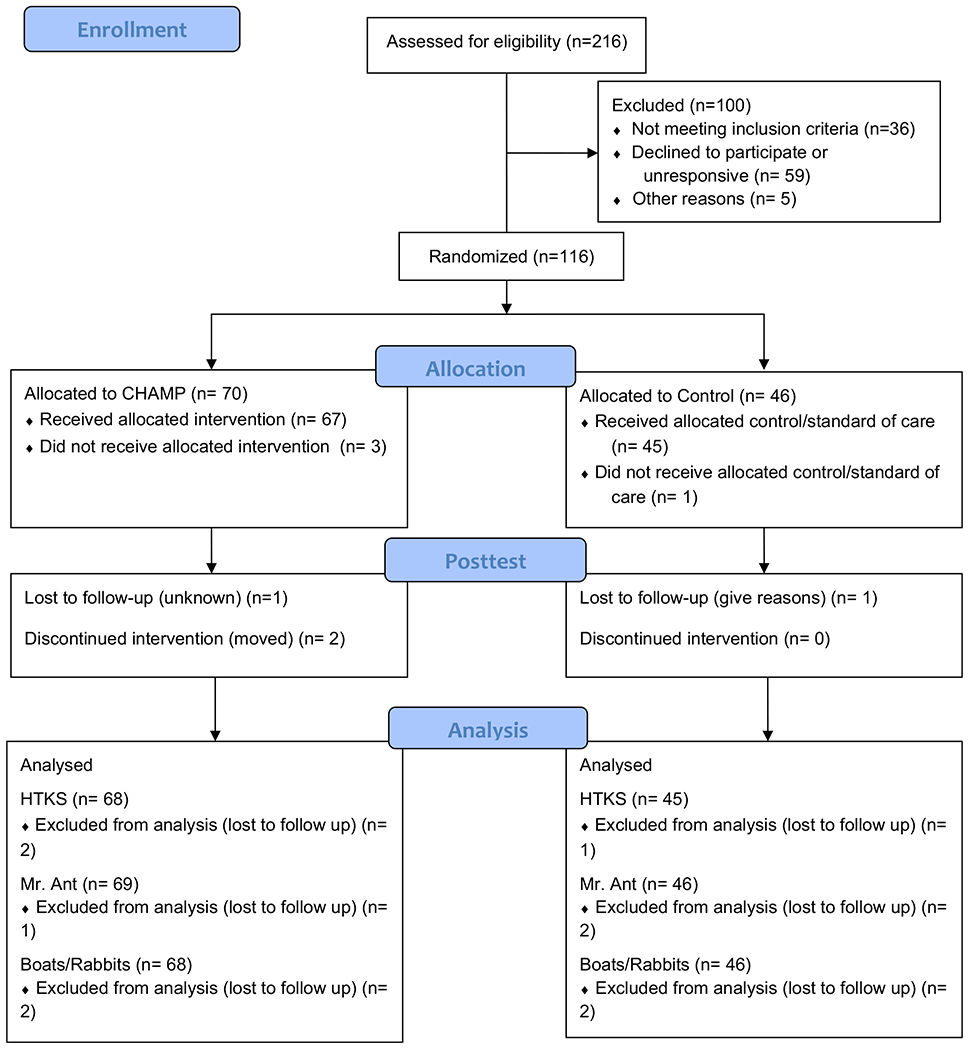

Parents/guardians received a letter introducing the study in preschool welcome packets and were compensated $5 for returning a consent form. Given the cluster randomization by classroom, children whose parents did not consent could be in CHAMP classrooms, but these children were not assessed or included as study participants. Classrooms were randomly assigned to receive either CHAMP or the control condition (outdoor recess). CHAMP was implemented during the preschool year; evaluation assessments were conducted prior to CHAMP start (pre-test; September/October) and within 2 weeks after CHAMP had concluded (post-test; April/May). See the CONSORT diagram (Figure 1) for sample and recruitment details; sample size calculations were that with 70 children in the intervention and 50 children in the control group, we would have 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.52 with a Type 1 error level of 0.05.23 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00133319) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03189862). Informed consent was obtained from parents and child verbal assent was obtained during assessments.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT Diagram

2.2 |. Participants

We enrolled 116 preschoolers (mean age = 53.4 months at enrollment; range: 45–60 months; 68 girls). Sample race/ethnicity was 68% African-American; 13% White, 5% Hispanic, 14% Bi-racial/Other.

2.3 |. Intervention

CHAMP has been shown to improve child motor skills, physical activity, and perceived motor competence.1,15 Grounded in Achievement Goal Theory, CHAMP creates a mastery climate for learning and practicing motor skills. The mastery climate encourages children to learn and develop new motor skills, increase their level of motor competence, and achieve a sense of motor skill mastery based on their perceptions. CHAMP uses specific learning environment structures that have been identified as critical for creating mastery climates. These TARGET structures (Task, Authority, Recognition, Grouping, Evaluation, and Time) encourage children to select their own activities that range in difficulty (Task), choose their own goals/activities to work on (Authority), review their own performance (Recognition), choose with whom and how they engage in the activities (Grouping), self-monitor their progress regarding their own performance and not the performance of others (Evaluation), and participate in activities as long as desired (Time).24,25 CHAMP’s application of TARGET structures may support cognitive and behavioral SR development by encouraging self-navigated engagement, planning and self-selected goal-setting, and self-paced learning (see Table 1).23

TABLE 1.

CHAMP intervention TARGET structures and links to SR

| TARGET Structure | Use of TARGET Structure in CHAMP to Promote SR |

|---|---|

| Task: Provide a variety of tasks/activities that vary in difficulty | Self-select from tasks/activities that vary in difficulty (create goals and strategies, plan and implement actions, make decisions, self-manage, self-monitor, and self-correct behavior) |

| Authority: Foster by allowing children to actively participate in the decision-making process | Self-manage and self-monitor behaviors (create goals and strategies, plan and implement actions, make decisions, self-manage, self-monitor, and self-correct behavior, manage emotions, understand and appropriately navigate social environments) |

| Recognition: Instructor and child recognize individual progress. Feedback is provided privately and individually. | Self-monitor and evaluate own performance (self-monitor behaviors, self-reflection of progress, manage emotions, focus attention, persist on a task, understand and appropriately navigate social environments, collaborative efforts) |

| Grouping: Focuses on grouping patterns Children are not grouped but given the opportunity to self-select their engagement with others | Self-select own engagement in task; give child ability to self-govern learning experience (plan actions and make decisions, self-monitor behavior, self-correct behaviors, manage emotions, appropriately navigate social environments, collaborative efforts) |

| Evaluation: Determine progress based on self-norms, not global norms | Self-evaluate own performance (self-monitor behaviors, self-reflection of progress, manage emotions, focus attention) |

| Time: Individualize the pace of instruction and learning experience | Self-direct own learning (plan actions and make decisions, self-monitor behaviors, self-correct behaviors, manage emotions) |

Due to logistical considerations at the schools, we were unable to complete the intervention dose proposed in trial registration. Instead, CHAMP was implemented 3 days a week for 16 weeks from November–April (48 sessions, 45-minute/session, total dose = 2160 min). Each session consisted of the following: (1) 2 min warm-up activity, (2) 3–4 min of motor skill instruction, (3) 32–35 min of autonomy-based motor skill engagement, in which children were free to choose which activity to practice and attempt, and (4) a 2–3 min closure activity. Two graduate student instructors led each session. One had 6 years of previous experience with CHAMP and the other had a background in physical education.

2.3.1 |. CHAMP fidelity checks

Fidelity checks were completed daily. The fidelity checklist was specifically developed for the CHAMP intervention (see supplemental material). This checklist included 10 of the 12 items from the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR).26,27 Specifically, the checklist included information on name [TIDieR #1], why/rationale/goal elements [TIDieR #2], procedures/activities/process [TIDieR #4], who provided [TIDieR #5], where [TIDieR #7], when and how much [TIDieR #8], tailoring [TIDieR #9], modification [TIDieR #10], how well/planned [TIDieR #11], and how well/actual [TIDieR #12]. TIDier #3, what/materials, was not included on the checklist, but daily photographs were recorded of the intervention setup to ensure documentation of all materials used. TIDier #6, how, was not considered needed as the mode of delivery was always in person by a trained member of the research team. To mitigate potential bias in reporting, fidelity checks were completed by two research team members who were not the primary CHAMP instructors. CHAMP was implemented with high fidelity; 100% of intervention sessions included all instructional elements and incorporated all TARGET structures properly.

2.4 |. Control condition

Children in the control group participated in the standard of care which was a daily free play session (i.e., recess). These sessions took place on either the outdoor school playground or inside a large, ample indoor open space. The playground included an open grassy area, fixed playground equipment, swings, basketball hoops, etc., while the indoor play areas included balls, hoppy balls, scooters, etc. The outdoor and indoor play areas and equipment were designed for gross motor play and appropriate physical activity engagement but no formalized motor skills instruction was provided.

2.5 |. Measures

Parents reported on child sex (male or female), age (months), and race/ethnicity. Behavioral and cognitive SR were assessed at pre-test and post-test by trained research assistants using direct assessment and standardized computer-based tasks. Standardized instructions were read aloud by the assessor or as part of the computer task. Research assistants were not blinded to participant group assignment.

2.5.1 |. Behavioral aspects of self-regulation

Behavioral SR was assessed using the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders Task (HTKS).4 The HTKS requires the child to enact behaviors in response to a series of commands, while inhibiting dominant responses. For example, children are told “Touch your head” and must touch their toes. To execute the task, children must remember the rules, inhibit their initial behavioral reaction, and change their behavioral response to the opposite of the verbal instruction. The HTKS includes three parts, each including verbal instructions and between 4–6 practice trials preceding 10 test trials. All practice and test trials are scored from 0–2 points. Children receive a 2 if they successfully complete the trial, 1 if they self-correct during a trial, or 0 if they fail to complete the trial correctly. Children advance if they receive at least 4 points during the test trials. In the first part, children touch their head and their toes. In the second part, children add their knees and shoulders so that they must touch their head when asked to touch toes and touch their knees when asked to touch shoulders. In the third and final part, the rules are switched so that head goes with knees and shoulders go with toes. HTKS trials were coded live by trained administrators who achieved inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation = 0.99) before assessment. Total number of points earned in test (not practice) trials are summed to generate HTKS score (range: 0–60), with higher scores indicating better behavioral SR. The HTKS has been shown to be reliable and valid with diverse samples of preschool-aged children.4,28

2.5.2 |. Cognitive aspects of self-regulation

Cognitive SR was assessed using computerized tasks assessing visual–spatial working memory (“Mr. Ant”) and cognitive flexibility (“Boats and Rabbits”) from the Early Years Toolbox (EYT), a normed collection of iPad-based game-like tasks. The EYT has demonstrated expected developmental sensitivity and shown good convergent validity with comparable NIH Toolbox tasks with fewer floor effects in a large, diverse sample of Australian children ages 2.5–5 years.29

Working memory

In “Mr. Ant,” children are presented with a cartoon ant figure who “puts” stickers on different body parts. Children must remember the location of each sticker and put it back on Mr. Ant. The game includes eight progressive levels with three trials each (level 1 = 1 sticker; level 8 = 8 stickers). Children must correctly place stickers in at least one trial to progress to the next level. Children advance until they fail to get all three trials correct. Children receive 1 point for each level completed with at least two correct trials and 1/3 of a point for levels with only 1 correct trial. The total number of earned points is summed across the assessment (0–8), with higher scores indicating better cognitive SR.

Cognitive flexibility

“Rabbits & Boats” is a dimensional card-sorting task. Children are shown six stimuli “cards” at a moat bifurcation and instructed to sort the cards into the correct castle at the end of each moat. Cards are sorted based on shape (rabbit vs. boat) or color (red vs. blue). The game has three series: pre-switch, post-switch, and border-task phases. Children sort by color (red vs. blue) in the pre-switch series; shape (boat vs. rabbit) in the post-switch series; and by either shape or color depending on whether a card is surrounded by a black border in the border-task series. Each series includes two practice trials and six test trials. Children receive a point for each correctly sorted card and must receive at least 5 points in both the pre-and post-switch series to progress to the border-task series. Total number of correctly sorted cards (post-switch) are summed (range: 0–12). Higher scores indicate better cognitive SR.

2.6 |. Statistics

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables, were computed to summarize characteristics of the overall sample and of the intervention and control groups. Between-group comparisons were conducted using two-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate to evaluate the success of randomization and unadjusted group differences in behavioral and cognitive aspects of SR at pre-test. Bivariate associations among pre-and post-test behavioral and cognitive SR indicators were assessed using correlations.

As initial inspection of the distributions revealed many zero scores for all SR variables, we tested the impact of CHAMP on each SR outcome using zero-inflated random effect hurdle models.30 These mixed-effect regression models can account for non-normal distributions with zero-inflated scores. They simultaneously model the likelihood that a child in the intervention condition, compared to control, will have a non-zero SR score at post-test (“zero-inflated” component of model), and that given a non-zero score, how much a child in the intervention condition compared to control will increase in SR from pre-to post-test (“conditional” component of model). Comparisons between intervention and control groups at pre- and post-test were conducted using these models, including child age, child sex, and timepoint of assessment as covariates that could predict SR. Model selection was done using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).31 A quasi-Poisson family was chosen to handle overdispersion.32

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations

See Table 2 for pre-and post-test sample sizes, means, and percent of children scoring zero on each task for the total sample and intervention and control groups. Percent of zero responses at pre-test and post-test did not differ between intervention and control groups (all p’s > 0.05). Table 3 presents bivariate correlations among SR outcomes at pre-and post-test.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics and unadjusted group comparisons for SR variables (M, SD include zero scores)

| Total Sample |

Intervention |

Control |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Wave | N | M(SD) | % scoring zero | N | M(SD) | % scoring zero | N | M(SD) | % scoring zero |

| HTKS | Pre | 114 | 4.77 (8.99) | 57 | 69 | 5.83 (10.20) | 54 | 45 | 3.16 (6.54) | 60 |

| Post | 112 | 11.0 (14.30) | 38 | 68 | 13.0 (15.00) | 31 | 44 | 8.05 (12.70) | 50 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mr. Ant | Pre | 116 | 1.64 (2.20) | 54 | 70 | 1.73 (2.28) | 51 | 46 | 1.50 (2.07) | 59 |

| Post | 112 | 2.68 (2.68) | 40 | 68 | 2.68 (2.79) | 41 | 44 | 2.68 (2.53) | 39 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Boats/Rabbits | Pre | 114 | 2.08 (3.19) | 59 | 68 | 2.25 (3.32) | 55 | 46 | 1.83 (3.01) | 63 |

| Post | 112 | 4.71 (3.97) | 27 | 68 | 4.62 (4.07) | 28 | 44 | 4.86 (3.86) | 25 | |

TABLE 3.

Bivariate correlations among behavioral and cognitive SR variables at pre-test (below diagonal) and post-test (above diagonal)

| HTKS | Mr. Ant | Boats/Rabbits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTKS | 0.59*** | 0.32*** | 0.29** |

| Mr. Ant | 0.26** | 0.54*** | 0.34*** |

| Boats/Rabbits | 0.19* | 0.29** | 0.25** |

Note: Values on the diagonal indicate autocorrelation or stability of each measure from pre- to post-test.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

3.2 |. Intervention effects

The zero-inflated random effect hurdle models simultaneously tested for impact of intervention condition on the odds of earning a non-zero score at post-test and the likelihood of increasing one’s score given that the child achieved a non-zero score. Models included child sex, age at pre-test, and timepoint of assessment (pre-test; post-test) as covariates.

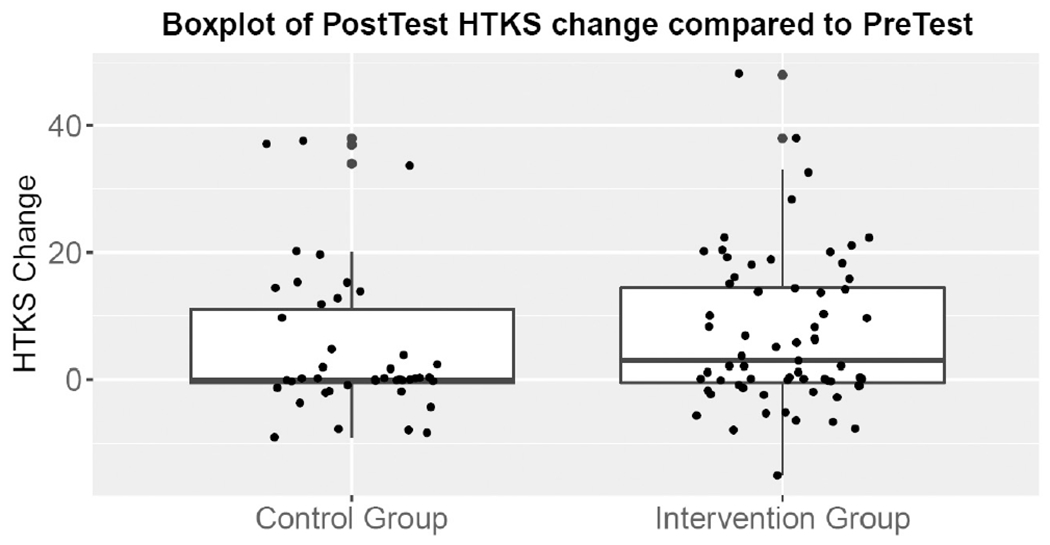

Overall, results indicated that there was an intervention effect on behavioral SR (HTKS), but only for the odds of earning a non-zero score at post-test (p < 0.001), not on cognitive SR indicators (Mr. Ant conditional model p = 0.96, zero-inflated model p = 0.15, Boats/Rabbits conditional model p = 0.94, zero-inflated model p = 0.44). Table 4 presents results of the mixed effects hurdle model estimating impact of intervention receipt on HTKS scores. Results from the zero-inflated part of the model indicate that children receiving the intervention, compared to not, were almost 3 times more likely to have non-zero scores at post-test; OR: 2.98 (CI 1.53, 5.81). Results from the conditional part of the model indicate that assuming the child achieved a non-zero score, the intervention did not have a significant impact on HTKS (RR 1.00, CI 0.63, 1.59). Figure 2 presents boxplots of the HTKS score changes after intervention compared to pre-intervention for the intervention and control groups.

TABLE 4.

Mixed-effect hurdle model results testing impact of CHAMP on HTKS (n = 112)

| Zero-Inflated Component (odds of non-zero score at post-test) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Predictor Variable | Regression Coefficient (Unstandardized B) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p value |

| Intervention Receipt | 1.09 | 2.98 (1.53, 5.81) | 0.001 |

| Conditional Component (post-test score, conditional on having non-zero score) | |||

|

| |||

| Predictor Variable | Regression Coefficient (Unstandardized B) | Relative Ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|

| |||

| Intervention Receipt | 0.002 | 1.00 (0.63, 1.59) | 0.99 |

|

| |||

| Covariates | |||

| Timepoint: Post-test vs. Pre-test | 0.57 | 1.76 (1.12, 2.77) | 0.014 |

| Child Sex: Male vs. Female | −0.49 | 0.62 (0.41, 0.93) | 0.02 |

| Child Age at Pre-test | 0.04 | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 0.24 |

FIGURE 2.

Intervention results: Boxplots of HTKS changes at post-test compared to pre-test for the intervention and control groups

3.3 |. Age, sex, and timepoint of assessment as predictors of self-regulation

Covariates were not significant predictors of odds of earning a non-zero score at post-test (all p’s < 0.05). Results from the conditional component of the model indicated that pre-test age was not significantly associated with HTKS score, but that timepoint of assessment (post vs. pre-test) and child sex (girls vs. boys) was associated with increased HTKS score, regardless of intervention condition. The timepoint of assessment finding indicates that among children who earned a non-zero HTKS score, post-test HTKS scores increased by 76% (calculated as exp(Beta 0.57)-1, p = 0.014) compared to pre-test, regardless of intervention condition. The child sex finding indicates that among children who earned a non-zero HTKS score, boys’ expected mean HTKS scores were only 62% (calculated as exp(Beta 0.49)-1, p = 0.02) as high as girls’ scores (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Boys’ and girls’ HTKS scores at pre-and post-test

4 |. DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to test the impact of a mastery-oriented motor competence intervention delivered in preschool settings serving children from low-income families on child behavioral and cognitive SR. We found that: (1) the CHAMP intervention had effects on behavioral, but not cognitive aspects of SR, and only among children who scored zero at pre-test; (2) child factors, including being a girl and having longer classroom exposure/maturation were associated with improved behavioral SR regardless of intervention condition; and (3) behavioral and cognitive SR scores were generally low, and moderately intercorrelated across domains. Results are discussed regarding implications for SR assessment and the potential for mastery-focused group learning climates and movement interventions to enhance SR during the preschool years.

4.1 |. Impacts on behavioral and cognitive aspects of self-regulation

Many interventions that have specifically targeted cognitive SR skills such as working memory have yielded mixed or limited impact; the challenge of “near” versus “far” transfer of cognitive SR skills in cognitive training studies has been well-described.33 The finding that CHAMP impacted behavioral, but not cognitive aspects of SR was consistent with these observations as well as prior literature on motor skills interventions. Motor competence requires planning, monitoring, and controlling large muscle groups, skills that are a focus of CHAMP and proximally related to behavioral SR.34 Prior motor skills interventions with children have shown impacts on behavioral SR. For example, among 107 preschoolers, children receiving a gross motor skills intervention demonstrated better behavioral SR (HTKS) 6 weeks later compared to controls,11 and a prior evaluation of CHAMP showed impacts on behavioral SR as assessed using a snack delay task.1 An 8-week intervention involving both fine and gross motor activities found impacts on both aspects of SR, but greater effects for behavioral (inhibitory control) compared to cognitive aspects (working memory) among only 53 preschoolers.10 In contrast, our 16-week intervention did not improve cognitive SR. Researchers have noted that fine motor competence and behavioral SR skills are only modestly related and that each contributes distinctly to early school achievement.9,35 Hudson et al10 may have found improvements in cognitive SR because their intervention included fine motor skill components that may be closely connected to cognitive control pathways,8 whereas CHAMP’s focus on gross motor skills may explain its impacts on behavioral SR. Motor skills interventions that integrate both fine-and gross-motor skill practice may be a promising direction for enhancing both aspects of SR9,34; to inform such work, future observational research should articulate specificity in associations of fine versus gross motor skills across different SR domains.

4.2 |. Mastery climates for motor competence

Prior classroom-based interventions that have impacted cognitive SR in young children, such as Tools of the Mind,36 seek to promote mastery by fostering autonomy and choice, similar to CHAMP, which does so in a motor context. It has been suggested that physical activity interventions that stimulate cognition may be most effective for improving SR, specifically executive functioning skills (PESCE 2021; DOI:10.1080/1750984X.2021.1929404), although results with older children have been mixed.37 Mastery-oriented interventions permit children to control their own learning experience, maintaining cognitive engagement, and motivation to learn as they focus on improving their own performance rather than making normative or social comparisons.15 In CHAMP, children select their own goals, activities, and with whom they engage in those activities. CHAMP’s mastery climate challenged children to master increasingly difficult motor skills, which engaged behavioral SR skills (e.g., inhibiting muscle movements).14,17 It is possible that CHAMP did not equally challenge working memory or cognitive flexibility, resulting in improved behavioral but not cognitive SR. The cognitive challenge of engaging in specific, mindful movements may also be important for enhancing cognitive aspects of SR;9,34,38 applying such techniques in mastery-focused learning climates may yield positive results. Mastery-focused motor competence interventions with young children could also promote cognitive SR over time through indirect pathways. For example, a mastery-oriented motor skills intervention that enhanced children’s motor competence could increase their cognitive and emotional engagement in physical activity and determination to seek out greater physical learning challenges in future, which in turn could enhance cognitive aspects of SR via neurobiological and cognitive stimulation pathways.12,38,39 Future longitudinal studies could disentangle these pathways as well as determine whether there are “sleeper effects” on cognitive aspects of SR for children who participated in mastery-oriented motor competence interventions as preschoolers.

4.3 |. Child and socialization factors predicting self-regulation growth

We found that regardless of intervention, child sex – specifically, being a girl – and timepoint of assessment – specifically, post-test compared to pre-test – were associated with increased behavioral SR. The timepoint effect suggests a strong “over time” component to behavioral SR. This finding could reflect maturation, longer exposure to the classroom context, or both. Prior work using school cutoff designs that can disentangle “schooling effects” from developmental maturation suggests that both maturation (e.g., related to brain development) and experiencing the structure of preschool (e.g., classroom routines) can promote behavioral SR.20,40 The current study design could not tease apart preschool experience and maturational factors, but this is an important question for future work. The finding that girls improved their SR more than boys could also reflect generally greater early-life immaturity of males,41 socialization of gendered expectations for behavior control,42 or their combination. Although CHAMP intervention effects on motor competence were not found to differ for boys and girls in prior work,43 other motor interventions have found sex-specific effects, including on SR outcomes. For example, among preschoolers from low-SES communities, a rhythm, and movement intervention designed to practice SR skills improved attention-shifting cognitive SR skills for boys, but not girls.44 Such individual differences in response to intervention have also been discussed in the cognitive training SR literature.45 Future research on motor skills interventions that seek to improve SR for young children thus may also benefit from unpacking how sex differences or other individual factors such as maturation and/or socialization may drive intervention impacts.

4.4 |. Assessment implications

Like other studies finding that intervention effects are stronger for children performing poorly at pre-test,10 we found that CHAMP primarily increased the odds of children obtaining non-zero HTKS scores, rather than increasing scores for children with non-zero scores. As in prior work with the HTKS35 and EYT,29 many children in our sample scored zero on SR measures. This may indicate floor effects and/or sample characteristics. Floor effects can occur particularly in young, high-poverty samples;46 recent work has sought to adapt the HTKS to address this concern.47,48 Although direct assessments like HTKS and computer-based tasks allow objective measurement, it may also be helpful to combine them with teacher reports.49 Floor effects on direct assessments may be due to competence-performance distinctions, for example, such that children who may possess SR skills cannot perform them for the examiner in the moment. Although it may be easier for young children to demonstrate SR skills in a behavioral task like HTKS compared to more abstract computer tasks, HTKS is still an individually administered assessment that may evoke anxiety, resulting in poor performance.

Although the HTKS has been validated for use in diverse samples,28 it is also increasingly recognized that SR interventions should occur in contextually meaningful contexts33; this also applies to SR assessment. Our sample of preschoolers from low-income families was challenged by these tasks, consistent with prior literature,18,35,46 but also suggesting a need for alternate assessment methods that are contextually relevant as well as easy to administer, like the HTKS-R.47 Finally, as expected and as other studies have found,50 we found that individual behavioral and cognitive SR indicators were moderately intercorrelated, confirming the multifaceted nature of the SR construct and the importance of multiple measurement approaches.

4.5 |. Strengths and limitations

The current study had several strengths, including the cluster-randomized RCT design, which allowed us to determine the effectiveness of CHAMP compared to outdoor recess. CHAMP was also administered with high fidelity, which is recommended but not always assessed in physical activity-focused interventions.38 Further, we focused on children from low-income families, who often experience SR difficulties given exposure to chronic stressors.18 As with all studies, there were also limitations. First, reflecting challenges in the field,2,3 SR assessments may overlap conceptually. For example, to successfully complete the HTKS, children must be able to enact the behavioral skills of inhibiting prepotent responses and engaging alternate responses, yet HTKS also requires cognitive SR (e.g., working memory to recall instructions; cognitive flexibility to act opposite to instructions). Thus, HTKS measures complex SR skills.47 Similarly, although working memory and cognitive flexibility index cognitive SR, they also require behavioral responses (e.g., fine motor skills). Second, although examiners were trained to reliability on SR task administration, children’s general poor performance may have reflected limited understanding. A strength of the hurdle model approach was that it allowed us to account for this non-normal distribution by simultaneously modeling non-zero and zero-value scores, which yielded unique information about both how the intervention worked among children who scored poorly and those who had non-zero scores. Finally, as our sample included only children living in poverty and attending Head Start, our findings are not generalizable beyond this population.

4.6 |. Perspective

Motor competence interventions that use mastery-oriented approaches to instruction are an appealing way to engage children in activities that may enhance behavioral aspects of SR, although effects were specific to children who received zero scores at pre-test. There was no evidence that such interventions enhanced cognitive SR. CHAMP provides a mastery-oriented approach to motor skill instruction that engages children in self-selected gross motor skill activities in a non-competitive context. It was shown to be effective for improving motor outcomes14 and, to some degree, SR.1 Current findings expand on this work and suggest that this mastery-oriented motor competence intervention effectively improves behavioral SR, but only for children who performed poorly on the behavioral SR assessments. It is important to consider mastery-oriented motor competence interventions like CHAMP as an effective approach to improving not only motor skills but also behavioral SR in young children, as each of these factors can have important and lasting impacts on children’s development and health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. The authors thank the Head Start Centers that participated in this project and the following individuals for their assistance with data collection – Katherine Scott-Andrews, Katherine Chinn, Indica Sur, Carissa Wengrovious, Emily Meng, and Sanne Veldman, along with several Undergraduate Research Assistants.

FUNDING INFORMATION

National Institutes of Health (NIH): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) / Common Fund/Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), Science of Behavior Change (SOBC) Initiative, NHLBI/OBSSR R01-HL-132979 02S1.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available from authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robinson LE, Palmer KK, Bub KL. Effect of the Children’s health activity motor program on motor skills and self-regulation in head start preschoolers: an efficacy trial. Frontiers. Public Health. 2016;4:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClelland MM, Cameron CE. Self-regulation in early childhood: improving conceptual clarity and developing ecologically valid measures. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6(2):136–142. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigg JT. Annual research review: on the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(4):361–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Duncan R, et al. Predictors of early growth in academic achievement: the head-toes-knees-shoulders task. Front Psychol. 2014;5:00599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker DR, Miao A, Duncan R, McClelland MM. Behavioral self-regulation and executive function both predict visuomotor skills and early academic achievement. Early Child Res Q. 2014;29(4):411–424. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montroy JJ, Bowles RP, Skibbe LE, Foster TD. Social skills and problem behaviors as mediators of the relationship between behavioral self-regulation and academic achievement. Early Child Res Q. 2014;29(3):298–309. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haubenstricker J, Seefeldt V. Acquisition of motor skills during childhood. In: Seefeldt V, ed. Physical Activity and Well-Being. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance; 1986:49–110. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Fels IMJ, te Wierike SCM, Hartman E, Elferink-Gemser MT, Smith J, Visscher C. The relationship between motor skills and cognitive skills in 4–16 year old typically developing children: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(6):697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClelland MM, Cameron CE. Developing together: the role of executive function and motor skills in children’s early academic lives. Early Child Res Q. 2019;46:142–151. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson KN, Ballou HM, Willoughby MT. Short report: improving motor competence skills in early childhood has corollary benefits for executive function and numeracy skills. Dev Sci. 2020;24(4):e13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulvey KL, Taunton S, Pennell A, Brian A. Head, toes, knees, SKIP! Improving preschool Children’s executive function through a motor competence intervention. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2018;40(5):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubans D, Richards J, Hillman C, et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: a systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomporowski PD, Pesce C. Exercise, Sports, and Performance Arts Benefit Cognition Via a Common Process. Psychol Bull. 2019;145(9):929–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer KK, Chinn KM, Robinson LE. Using achievement goal theory in motor skill instruction: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2017;47(12):2569–2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson LE. Effect of a mastery climate motor program on object control skills and perceived physical competence in preschoolers. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2011;82(2):355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stodden DF, Goodway JD, Langendorfer SJ, et al. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: an emergent relationship. Quest. 2008;60(2):290–306. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer KK, Cox ER, Scott-Andrews KQ, Robinson LE. Structured observations of child behaviors during a mastery-motivational climate motor skill intervention: an exploratory study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raver CC. Low-income children’s self-regulation in the classroom: scientific inquiry for social change. Am Psychol. 2012;67(8):681–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brian A, Pennell A, Taunton S, et al. Motor competence levels and developmental delay in early childhood: a multicenter cross-sectional study conducted in the USA. Sports Med. 2019;49(10):1609–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison FJ, Ponitz CC, McClelland MM. Child Development at the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition. Self-Regulation and Academic Achievement in the Transition to School. American Psychological Association; 2010:203–224. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews JS, Ponitz CC, Morrison FJ. Early gender differences in self-regulation and academic achievement. J Educ Psychol. 2009;101(3):689–704. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson LE, Wang L, Colabianchi N, Stodden DF, Ulrich D. Protocol for a two-cohort randomized cluster clinical trial of a motor skills intervention: the promoting activity and trajectories of health (PATH) study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e037497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson LE, Palmer KK, Riley HO, et al. Protocol for a two-cohort randomized cluster clinical trial of a motor skills intervention: The Promoting Activity and Trajectories of Health (PATH) Study. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(6): e037497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ames C Classrooms: goals, structures, and student motivation. J Educ Psychol. 1992;84(3):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein J Family structures and student motivation: a developmental perspective. Res on Motiv Educ. 1989;3:259–295. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotterill S, Knowles S, Martindale A-M, et al. Getting messier with TIDieR: embracing context and complexity in intervention reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caughy MOB, Brinkley DY, Pacheco D, et al. Self-regulation development among young Spanish-English dual language learners. Early Child Res Q. 2022;60:226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard SJ, Melhuish E. An early years toolbox for assessing early executive function, language, self-regulation, and social development: validity, reliability, and preliminary norms. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2016;35(3):255–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min Y, Agresti A. Random effect models for repeated measures of zero-inflated count data. Stat Modelling. 2005;5(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aho K, Derryberry D, Peterson T. Model selection for ecologists: the worldviews of AIC and BIC. Ecology. 2014;95(3):631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breslow N Tests of hypotheses in Overdispersed Poisson regression and other quasi-likelihood models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1990;85(410):565–571. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smid CR, Karbach J, Steinbeis N. Toward a science of effective cognitive training. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2020;29(6):531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leshem R, de Fano A, Ben-Soussan TD. The implications of motor and cognitive inhibition for hot and cool executive functions: the case of Quadrato motor training. Front Psychol. 2020;11:940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cameron CE, Brock LL, Murrah WM, et al. Fine motor skills and executive function both contribute to kindergarten achievement. Child Dev. 2012;83(4):1229–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blair C, Raver CC. Closing the achievement gap through modification of neurocognitive and neuroendocrine function: results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of an innovative approach to the education of children in kindergarten. PLOS One. 2014;9(11):e112393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulten R, Bedard C, Graham JD, Cairney J. Effect of cognitively engaging physical activity on executive functions in children. Front Psychol. 2022;13:841192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pesce C, Vazou S, Benzing V, et al. Effects of chronic physical activity on cognition across the lifespan: a systematic meta-review of randomized controlled trials and realist synthesis of contextualized mechanisms. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2021;1–39:1-39. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker DR, Nader PA. Run fast and sit still: connections among aerobic fitness, physical activity, and sedentary time with executive function during pre-kindergarten. Early Child Res Q. 2021;57:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skibbe LE, Connor CM, Morrison FJ, et al. Schooling effects on preschoolers’ self-regulation, early literacy, and language growth. Early Child Res Q. 2011;26(1):42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexander GM, Wilcox T. Sex differences in early infancy. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6(4):400–406. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barnett MA, Scaramella LV. Mothers’ parenting and child sex differences in behavior problems among African American preschoolers. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27(5):773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer KK, Harkavy D, Rock SM, Robinson LE. Boys and girls have similar gains in fundamental motor skills across a preschool motor skill intervention. J Mot Learn Dev. 2020;8(3):569–579. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams KE, Berthelsen D. Implementation of a rhythm and movement intervention to support self-regulation skills of preschool-aged children in disadvantaged communities. Psychol Music. 2019;47(6):800–820. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Shah P, Jonides J. The role of individual differences in cognitive training and transfer. Mem Cognit. 2014;42(3):464–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caughy MOB, Mills B, Owen MT, et al. Emergent self-regulation skills among very young ethnic minority children: a confirmatory factor model. J Exp Child Psychol. 2013;116(4):839–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzales CR, Bowles R, Geldhof GJ, Cameron CE, Tracy A, McClelland MM. The head-toes-knees-shoulders revised (HTKS-R): development and psychometric properties of a revision to reduce floor effects. Early Child Res Q. 2021;56:320–332. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McClelland MM, Gonzales CR, Cameron CE, et al. The head-toes-knees-shoulders revised: links to academic outcomes and measures of EF in young children. Front Psychol. 2021;12:72184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmitt SA, Pratt ME, McClelland MM. Examining the validity of behavioral self-regulation tools in predicting Preschoolers’ academic achievement. Early Educ Dev. 2014;25(5):641–660. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willoughby MT, Wirth RJ, Blair CB. Executive function in early childhood: longitudinal measurement invariance and developmental change. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(2):418–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available from authors upon request.