The price of prescription drugs to consumers are soaring to unaffordable levels.1 In seeking root causes, it is enlightening to examine the key role played by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMS). They are a major part of the problem.

How Did Pharmacy Benefit Managers Come About?

Almost by accident, health care in the United Sates is largely employer-based. Employer-based health insurance came about during World War II. In 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt, trying to control inflation, froze wages. War time businesses were not allowed to increase workers’ pay. In order to compete for workforces, employers began offering generous health care benefits.2

In 1943, the Internal Revenue Service decreed employer-based health insurance would be exempt from taxation. This made it cheaper to get health insurance through a job than by any other means. In 1940, about 9% of Americans had health insurance. By 2017, employer-based health insurance was the most common form of health coverage. About 167 million workers and dependents under the age of 65 had employer-based health insurance.3

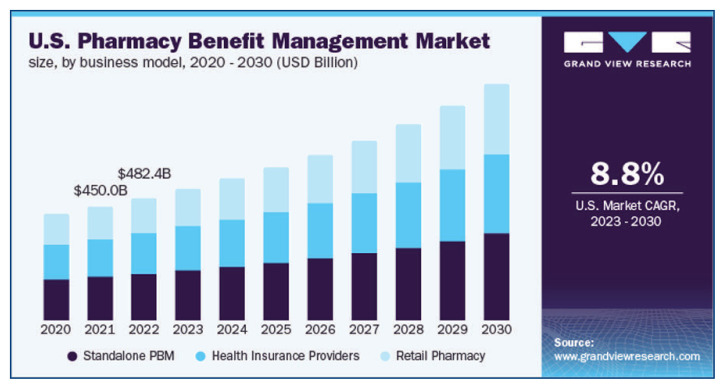

Prescription benefits are usually included with health care insurance. Over time these drug benefits have greatly expanded. For large corporations, these drug benefits have come to be managed by companies known as Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs).4

What PBMs Have Become

PBMs were supposed to lower health care costs. Due to rebates to PBMs this has not been the case. There is a growing belief, shared by the author, that PBMs increase drug costs. This has drawn the attention of Congress. In 2023, the US House of Representatives released an authoritative and insightful report on upward spiraling drug prices. The main findings are:5

PBMs affect patients’ health. PBMs often require burdensome prior authorization. This causes lengthy delays for approval of prescriptions. Patients suffer, and even die, while they wait for ‘authorization’.5 Conversely, some patients have to fail to respond to a more expensive drug even if a cheaper alternative exists. This is because the PBM has a financial incentive to compel the more expensive drug.

PBMs use their market leverage to increase their profits—not reduce costs for consumers. PBMs control which medications are included on a given health plan’s formulary. Drug manufacturers agree to discounts, or pay rebates, in order to get their products placed favorably on formularies. However, the discounts and rebates do not make their way down to the consumer. This substantial amount of money goes to the PBMs as profits. Drug manufacturers actually raise their prices due to PBMs. As PBMs demand larger and larger rebates or discounts, manufacturers offset these reductions by raising the “list” price for their drugs. PBMs encourage this practice because they receive larger financial rebates (e.g., PBM profits) from more expensive drugs.5

Incredibly PBMs own their own pharmacies. This ownership creates huge conflicts of interest, hurts competition, and distorts pricing. Another key function of PBMs is to establish a network of pharmacies where beneficiaries get can their prescriptions. The four largest PBMs: CVS, Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum Rx own their own pharmacies. This PMB group controls 80 percent of the market. Other smaller PBMs may own their own pharmacies. PBMs “steer” patients to the pharmacies they own or control making it difficult for independent pharmacies to survive.

Generally, PBMs reimburse independent pharmacies at lower rates and add additional fees. These PBM income creating fees can be for network participation or tied to PBM-generated metrics such as pharmacy rates of refills, errors, or audit compliance. These retroactive fees sometimes cost an independent pharmacy more to fill a prescription than it is reimbursed. For specialty pharmacies, they accrue fees based on irrelevant metrics.5

Driving Up the Cost

There are other ways PBMs drive up consumer costs. A ‘list price’ is similar to an automobile sticker price. Few car purchasers actually pay list price. Higher drug list prices drive up costs, even if patients pay a smaller discounted amount. Insurance premiums and copayments are based on list prices.

PBMs allegedly engage in a number of questionable practices. One of is “spread pricing” in which PBMs pay a lower amount to the pharmacist than they report to the health plan sponsor. The PBM pockets the difference. Sometimes they get caught. Using spread pricing, PBMs have overcharged state Medicaid programs in Ohio, Kentucky, Illinois, and Arkansas more than $415 million. It is difficult to determine the full extent of the impact of these PBMs practices; they certainly contribute to constantly increasing US healthcare costs.5

The report concludes greater transparency is necessary to determine the extent of the damage PBMs’ tactics are having on patients and the market place. Without further insight into PBM practices, it is difficult to determine the extent to which they create profits at the expense of patients and payors. It is essential these studies of PBMs be done expeditiously!

Billionaire Mark Cuban is taking on high drug prices and the PBMs with his company Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company. His company currently offers discount prices on 350 generic drugs. It has about 1.5 million customers. It could begin offering insulin directly to consumers in the near future.6

In July 2023 Cuban offered on his website a biosimilar version of the world’s highest grossing drug Humira at a 90% discount-about $569 vs. the current $6,922. Even with major discounts, Cuban expects to make a fair profit. Most people, especially the elderly, are not used to buying drugs on the internet. If the business model proves profitable, more companies may enter the market generating price-lowering competition.

A new paradigm in drug pricing may occur as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.7 Formerly Medicare, the largest national purchaser of drugs, could not negotiate prices on behalf of Medicare patients and US taxpayers.8 In 2026, Medicare will be able to negotiate drug prices with manufacturers without of ‘middle person’ of PBMs. This is definitely a step in the right direction.

Footnotes

Arthur H. Gale, MD, is a Missouri Medicine Contributing Editor. He is a retired Internal Medicine physician in St. Louis.

References

- 1.Blank Christine. Drug Makers Start 2023 With Price Hikes, Formulary Watch. 2023 January 4; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll Aaaron E. The Real Reason the US Has Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance. New York Times. 2017 September 5; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rook David. A Brief History of Employer-Sponsored Health Care {From the 1930s to Now}, HUB, Employees Benefits Blog. 2020 August 27; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Commonwealth Fund. Explainer, Pharmacy Benefit Managers and Their Role in Drug Spending. 2019 April 22; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comer Releases Report on PBMs’ Tactics leading To Soaring Prescription Drug Prices, Press Release. 2021 December 10; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovelace Berkeley, Jr, Dunn Lauren, McFadden Cynthia. Mark Cuban’s Next Act on Drug Costs: Tackling Insulin [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Releases Guidance For Historic Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program for Drug Program for price Applicability Year 2O26 2023 March 15; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pear Robert. Bill to Let Medicare Negotiate Prices is Blocked. New York Times; Apr 18, 2007. [Google Scholar]