Abstract

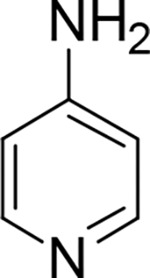

4-aminopyridine (4AP) is a potassium (K+) channel blocker used clinically to improve walking in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). 4AP binds to exposed K+ channels in demyelinated axons, reducing the leakage of intracellular K+ and enhancing impulse conduction. Multiple derivatives of 4AP capable of blocking K+ channels have been reported including three radiolabeled with positron emitting isotopes for imaging demyelinated lesions using positron emission tomography (PET). Here, we describe 3-fluoro-5-methylpyridin-4-amine (5Me3F4AP), a novel K+ channel blocker with potential application in PET. 5Me3F4AP has comparable potency to 4AP and the PET tracer 3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine (3F4AP). Compared to 3F4AP, 5Me3F4AP is more lipophilic (logD = 0.664 ± 0.005 vs. 0.414 ± 0.002) and slightly more basic (pKa = 7.46 ± 0.01 vs. 7.37 ± 0.07). In addition, 5Me3F4AP appears to be more permeable to an artificial brain membrane and more stable towards oxidation by the cytochrome P450 enzyme family 2 subfamily E member 1 (CYP2E1), responsible for the metabolism of 4AP and 3F4AP. Taken together, 5Me3F4AP has promising properties for PET imaging warranting additional investigation.

INTRODUCTION

4-aminopyridine (4AP) is a potassium channel blocker commonly used in the symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) (Stefoski et al., 1987; Goodman et al., 2009; Jensen et al., 2014). Its mechanism of action involves binding from the intracellular side to voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels exposed due to demyelination, thereby blocking the aberrant efflux of K+ ions and enhancing axonal conduction (Sherratt et al., 1980; Bostock et al., 1981; Kirsch et al., 1993; Fehlings and Nashmi, 1996; Rasband et al., 1998; Nashmi and Fehlings, 2001; Devaux et al., 2002; Arroyo et al., 2004; Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2004; Sinha et al., 2006). Additionally, 4AP has demonstrated potential clinical utility for spinal cord injury (Choquet and Korn, 1992; Hayes et al., 1993; Segal et al., 1999; Wolfe et al., 2001; Grijalva et al., 2003; Grijalva et al., 2010), traumatic brain injury (Radomski et al., 2022), and other diseases involving demyelination (Hayes, 2006). Based on the mechanism of action of 4AP, it has been proposed that upregulated K+ channels in demyelinated axons could be targeted for imaging demyelination using positron emission tomography (PET) (Brugarolas et al., 2018a; Brugarolas et al., 2018b). Thus, a radiofluorinated derivative of 4AP, [18F]3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine ([18F]3F4AP), was synthesized and evaluated for imaging demyelination (Brugarolas et al., 2016; Basuli et al., 2018; Brugarolas et al., 2018b). In those studies, [18F]3F4AP displayed high sensitivity in detecting demyelinated lesions in rodent models of MS (Brugarolas et al., 2018b) and non-human primates (Guehl et al., 2021b). Furthermore, [18F]3F4AP has shown acceptable radiation dosimetry in healthy human volunteers (Brugarolas et al., 2022) and it is currently undergoing evaluation in MS patients (Guehl et al., 2022) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04699747). Nevertheless, in humans [18F]3F4AP has shown lower metabolic stability (<50% parent fraction (PPF) remaining, 30 min post injection (Brugarolas et al., 2022)) than in monkeys (>90% PPF 2 h post injection (Guehl et al., 2021b)), which could potentially make its quantification challenging. This reduction in metabolic stability was found to arise from the inhibitory effect of isoflurane on the metabolism of [18F]3F4AP as evidenced by the fact that awake mice metabolize the tracer faster than anesthetized mice, with 20 ± 4 PPF vs. 65 ± 7 PPF respectively 35 min post-injection (Ramos-Torres et al., 2022). Additional studies indicate that [18F]3F4AP is oxidized at the 5-position to 5-hydroxy-3F4AP by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2E1 (Sun et al., 2023), which prompted us to look for more stable derivatives with suitable binding affinity and brain permeability.

Studies on 4AP derivatives including 3,4-diaminopyridine, 4-aminopyridine-3-methanol and others demonstrate that small substituents in the 3-position do not significantly impair binding to K+ channels (Kirsch and Narahashi, 1978; Berger et al., 1989; Caballero et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2009; Brugarolas et al., 2018b; Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). Based on this, several 4AP derivatives labeled with carbon-11, namely [11C]3-trifluoromethyl-4AP (Ramos-Torres et al., 2020), [11C]3-methoxy-4AP (Guehl et al., 2021a), and [11C]3-methyl-4AP (Sun et al., 2022), have also been investigated (Table 1). Although some of these derivatives possess advantages such as higher binding affinity and specific binding compared to [18F]3F4AP (Ramos-Torres et al., 2020), fluorine-18 labeled tracers are generally preferred due to their longer half-life (110 min vs. 20.3 min) (Pike, 2009). Furthermore, [18F]3F4AP displays excellent characteristics for PET imaging including a fast entry and washout from the brain mediated by a pKa value close to physiological (pKa = 7.65) and a positive logD (logD = 0.41) (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). In addition, recent studies have shown that 3-methyl-4AP has good binding affinity towards K+ channels, and thus, we hypothesized that a derivative of 3F4AP with a methyl group at the 5-position, 5Me3F4AP, would retain its ability to block Kv channels and have adequate brain permeability while exhibiting improved stability against metabolism. Herein, we characterized the pharmacological and biophysical properties of 5Me3F4AP and evaluated its in vitro metabolic stability towards CYP2E1 to investigate its potential as a PET tracer for imaging demyelination.

Table 1.

Structures of 4AP, 3F4AP, 3CF34AP, 3MeO4AP, 3Me4AP and their pKa, logD, Kv1 and EC50 values.

| drug |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| pKa | 9.58 | 7.65 | 7.17 | 9.18 | 9.82 |

| logD | −1.478 | 0.414 | 1.484 | −0.76 | −1.232 |

| IC50// M | 293 | 244 | 1061 | 807 | 40 |

| EC50//−M | 59.2 | 96.3 | --a | --a | --a |

(half-maximal inhibitory concentration) is the drug concentration at which 50% of current through Kv1 channels is blocked. EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) is the drug concentration at which the compound action potential of dysmyelinated nerves increases by 50%. All data in this table were previously reported: pKa, logD, and (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020) and EC50 values (Brugarolas et al., 2018b).

not available.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Studies Compliance:

Methods involving Xenopus laevis frogs were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and with the approval of the Comité Institucional del Cuidado y Uso de Animales en el Laboratorio at the University of Guadalajara (protocol: CUCEI/CINV/CICUAL-03/2023).

Materials:

5Me3F4AP was purchased from AmBeed Inc. (Arlington Hts, IL, USA). All other chemical compounds used for this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Merck (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) or as otherwise indicated.

Partition coefficient determination:

The octanol-water partition coefficient (logD) at pH 7.4 was determined according to our previous reported protocol (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). Briefly, PBS (900 μL), 1-octanol (900 μL), and a 10 mg/ mL aqueous solution of each compound (2 μL) were added to a 2 mL HPLC vial. The compounds were partitioned between the layers via vortexing and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 1 min to allow for phase separation. A 10 μL portion was taken from each layer (autoinjector was set up to draw volume at two different heights) and analyzed by HPLC. The relative concentration in each phase was determined by integrating the area under each peak and comparing the ratio of the areas from the octanol and aqueous layers. A calibration curve was performed to ensure that the concentrations detected were within the linear range of the detector (see Figure S1 and S2 in Supporting Information). This procedure was repeated four times for each compound.

Determination of pKa:

The pKa was determined using titration according to our previously described protocol (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). A 1 mg/mL solution of 5Me3F4AP was prepared, of which 5 ml was titrated with 0.01M HCl solution beyond the equivalence point. After each incremental addition of titrant, the sample was stirred and the pH reading was taken with a pH meter. The Gran plot of the titration was analyzed to obtain the pKa (see the plot in Supporting Information, Figure S3). A similar protocol was used to titrate 3F4AP and 4AP, respectively (Figures S4 and S5). The titration was repeated four times each for each compound.

Permeability rate determination:

The permeability rates of 5Me3F4AP and 3F4AP were determined using Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay- blood-brain barrier (BBB) kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Initially, solutions of each test compound were prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mM. These stock solutions along with the stock solutions of control compounds (high control: promazine hydrochloride, low control: diclofenac) were then diluted with PBS (pH = 7.2) to obtain the donor solutions with a final concentration of 500 μM. At the same time, 200 μM of equilibrium standards for each compound and a DMSO blank control solution were prepared.

In the experimental setup, 300 μL of PBS was added to the desired well of the acceptor plate, and 5 μL of BBB lipid solution in dodecane was added to membranes of the donor plate. Next, 200 μL of the donor solutions of each test compound and each permeability control were added to the duplicate wells of the donor plate. The donor plate was carefully placed on the acceptor plate and incubator for 18 hours at room temperature. After incubation, UV absorption measurements were conducted using 100 μL of the resulting solutions from the acceptor plate and the equilibrium standards. UV absorption of the controls was measured by running a UV scan in the range of 200 to 500 nm. UV absorption of 5Me3F4AP and 3F4AP was measured using HPLC equipped with a UV detector and C18 column. The calibration curve, demonstrating the relationship between the area under the curve (AUC) in the HPLC chromatogram and concentration, is presented in the Supporting Information (Figure S1, S2).

Cut-Open Voltage Clamp Electrophysiology:

Blocking potency of 5Me3F4AP was evaluated on the voltage-gated Shaker (homologous to mammalian Kv1.2) ion channel expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, as previously described (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). Briefly, each oocyte expressing the Shaker channel was voltage-clamped in a Cut-Open Voltage Clamp (COVC) station in order to elicit K+ currents in response to the voltage stimulus protocol, which entailed steps of 50 ms from −100 to 60 mV in increments of 10 mV. External and internal recording solutions for COVC were composed (in mM) of 12 KOH, 2 Ca(OH)2, 105 NMDG-MES, 20 HEPES and 120 KOH, 2 EGTA, and 20 HEPES, respectively, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with methylsufonate. For measurements achieved at pH = 9.1 or 6.4, HEPES was replaced by 2-(cyclohexylamino)-ethanesulfonic acid or 2-(N-Morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, respectively. Each oocyte expressing the Shaker ion channel was voltage-clamped to record K+ currents, first in the absence of 5Me3F4AP, and subsequently with the addition of 5Me3F4AP, from 0.0001 to 10 mM. Relative current (Irel) was quantified as the ratio of the current in the absence and in the presence of the indicated concentration of 5Me3F4AP. Finally, K+ currents were amplified with the Oocyte Clamp Amplifier CA-1A (Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and digitized with the USB-1604-HS-2AO Multifunction Card (Measurement Computing, Norton, MA, USA). All systems were controlled with the GpatchMC64 program (Department of Anesthesiology, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA) via a PC. Electrophysiology recordings were sampled at 100 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz.

Electrophysiology data analysis:

Data analysis was performed as previously described (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). Briefly, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 5Me3F4AP () was determined by fitting the Irel curve to the Hill equation at each value of V and pH. A Hill coefficient (h) in the range of 0.9<h<1.1 was used. Voltage and pH dependence of was analyzed by fitting the at each pH with a one-step model of inhibition (Woodhull model) which allowed the determination of the fractional distance through the membrane electrical field () that 5Me3F4AP has to cross to reach its binding site (Woodhull, 1973):

| Eqn.(1) |

where is the value of at is the Faraday constant, is the gas constant, is the room temperature, and is the apparent charge.

Mean values of data ± standard deviation (s.d.) are given or plotted and the number of experiments is denoted by n. Upper and lower limits of the 95% of confidence interval are denoted as and , respectively.

CYP2E1-mediated metabolic stability assessment:

The relative metabolic stability towards CYP2E1 was assessed with the competitive CYP2E1 inhibition assay utilizing the Life Technologies™ Vivid® CYP2E1 screening kit, as described in previous studies (Sun et al., 2023). In this assay, fluorescence emitted by the metabolic product of a specific CYP2E1 substrate included in the kit, was measured in the absence and presence of substrate competitors. Consequently, the highest fluorescence values were obtained from the blank experiments, lacking any competitors. As the concentration of competitors increased, or more potent competitors were introduced, the fluorogenic emission decreased accordingly.

Specifically, 40 μL of 2.5X (final concentration 25μM) solution of test compounds (4AP, 3F4AP, 5Me3F4AP, and positive control, i.e., tranylcypromine) in 1X Vivid® CYP2E1 reaction buffer was added to desired wells of a falcon black/clear 384-well plate in three replicates. Afterwards, 50 μL master pre-mix 2X (40 nM) CYP2E1 BACULOSOMES® and 2X (0.6 Units/mL) Vivid® regeneration system in 1X reaction buffer) was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow the compounds to interact with the CYP2E1 in the absence of enzyme turnover. Next, the reaction was initiated by adding 10μL per well of 10X (100 μM) Vivid® substrate (2H-1-benzopyran-3-carbonitrile,7-(ethoxy-methoxy)-2-oxo-(9Cl)) and 10X (300 μM) Vivid® NADP+ mixture. Immediately (in less than 2 minutes), the plate was transferred into the fluorescent plate reader and fluorescence was monitored over 60 minutes (reads in 1-minute intervals) at 415 nm as excitation wavelength and 460 nm as emission wavelength. The obtained reads were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9.

Determination of the IC50 of 5Me3F4AP to CYP2E1.

A similar Vivid® CYP2E1 assay was conducted as described above. Instead of testing a single concentration of 5Me3F4AP (final concentration 15μM), a series of concentrations (4.0 mM, 1.2 mM, 400 μM, 120 μM, 40 μM, 12 μM, 4.0 μM, 1.2 μM) were tested with three replicates for each concentration. The plate fluorescence was monitored over 60 minutes (reads in 1-minute intervals) at 415 nm as excitation wavelength and 460 nm as emission wavelength. The reads at 60 min (recalculated by the linear trend line equation) of each concentration were used and fitted with GraphPad Prism9 dose-response-inhibition (concentration is log) curve fitting to calculate the values. A similar procedure was used for determining the of 3F4AP.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

RESULTS

Basicity, lipophilicity and membrane permeability of 5Me3F4AP.

Measurements of these pharmacological parameters of 5Me3F4AP were taken and compared to those of its predecessors (Table 2). As indicated in column 2, 5Me3F4AP demonstrates slightly higher basicity in comparison to 3F4AP (7.46 ± 0.01 vs. 7.37 ± 0.07). Both compounds have pKa values that are close to the physiological pH, indicating their coexistence in both protonated and neutral forms under physiological conditions. In contrast, 4AP and 3Me4AP display greater basicity (pKa values above 9), indicating that the protonated form is predominant at physiological pH.

Table 2.

Pharmacological parameters for 5Me3F4AP, 3F4AP, 4AP and 3Me4AP.

| Drug | pKa | logD (pH 7.4) | Pe (nm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5Me3F4AP | 7.46 ± 0.01 | 0.664 ± 0.005 | 43.3 ± 0.5 |

| 4AP | 9.19 ± 0.03 | −1.478 ± 0.014a | 2.36 ± 0.03b |

| 3F4AP | 7.37 ± 0.07 | 0.414 ± 0.002a | 13.6 ± 0.5c |

| 3Me4AP | 9.82 ± 0.06a | −1.232 ± 0.008a | -- |

logD: experimental partition coefficient octanol: water at pH 7.4 (n =4).

pKa: experimental titration coefficient at room temperature (n =3).

Pe: permeability rate across the artificial membrane (n = 2).

previously reported data using the equipment and protocol (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020).

previously reported data (Brugarolas et al., 2018b).

result obtained during the present study, a value of 15.6 ± 0.6 nm/s was previously reported (Brugarolas et al., 2018b).

In terms of lipophilicity, 5Me3F4AP shows an octanol/water partition coefficient value at pH 7.4 of 0.664 ± 0.005 (Table 2. Column 3), which is higher than that of 3F4AP (logD = 0.414 ± 0.002). This result indicates that both compounds preferentially partition into the octanol layer, potentially facilitating faster permeation through a lipophilic membrane like the BBB via passive diffusion. Conversely, 4AP and 3Me4AP exhibit a preference for partitioning in the water layer (logD4AP = −1.478 ± 0.014, logD3Me4AP = −1.232 ± 0.008), suggesting slower permeation rates. This trend was further validated through a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay, which demonstrated that 5Me3F4AP permeates approximately three times faster than 3F4AP and 18 times faster than 4AP (Table 2. Column 4).

Affinity towards K+ channels.

The blocking potency at different pH conditions (6.4, 7.4 and 9.1) and voltages (−100 to 60 mV) of 5Me3F4AP was evaluated by measuring the K+ currents generated by Shaker voltage-gated potassium channel from D. melanogaster heterologously expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Figure 1). Specifically, Figure 1A shows three representative recordings elicited as a response to the voltage stimulus before and after the application of 1 mM of 5Me3F4AP under three extracellular pH conditions. From these recordings, it is clear that 1 mM 5Me3F4AP efficiently blocks the channels. Figure 1B shows the dose-response plot (relative K+ currents at 40 mV vs. 5Me3F4AP concentration) and the fitting of the experimental values to Hill equation to calculate . This plot shows that blocking is dose and pH dependent with less efficient blocking at higher pH. Figure 2C shows the calculated values at different values of pH. A model of electric field constant (Woodhull model, Equation 1) was used to determine their biophysical parameters and the electric fraction (), which represents the fraction of the electric field that the compound must cross through the channel pore to reach its binding site. This plot shows that the of 5Me3F4AP increases with voltage and pH indicating a drop in potency. and values determined from fitting the Hill and Woodhull equations are shown in Table 3 and compared to those of 4AP, 3F4AP, and 3Me4AP. These values confirm that at pH 7.4, the blocking potency of 5Me3F4AP to Kv channels is similar to that of 4AP and 3F4AP previously reported (Brugarolas et al., 2018b; Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020). In addition, when the pH was increased from 6.4 to 9.1, the of 5Me3F4AP (and 3F4AP) increased around 3-fold indicating lower potency. Conversely, the from 4AP and 3Me4AP decreased by approximately 4- and 3-fold, respectively, indicating higher potency at higher pH. These differences in pH dependence confirm that it is the protonated form that preferentially binds to channel, since 4AP and 3Me4AP exist mostly in their protonated state at this pH range, whereas 3F4AP and 5Me3F4AP are mostly protonated at pH 6.4 and predominantly neutral at pH 9.1. Finally, a δ value of ~0.4 was obtained for 5Me3F4AP; this value is consistent with the δ values of 4AP, 3F4AP and 3Me4AP previously reported (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020), and it indicates that this novel blocker binds at the same site within the Shaker pore traversing ~40% of the electric field generated across the lipid bilayer. Therefore, these findings demonstrate that the blocking potencies of these KV Shaker-related channel blockers produce a trend as follows: 3Me4AP > 3F4AP ~ 4AP ~ Me3F4AP.

Figure 1. Pharmacological and biophysical characterization of 5Me3F4AP upon Shaker KV ion channel.

(A), Representative recordings at pH values of 6.8, 7.4 and 9.1 elicited from three different oocytes expressing the Shaker channel before (upper, black) and after (lower, colored) the blockage with 1 mM of 5Me3F4AP. Currents were recorded as the response to voltage stimulus protocol that consisted of 50 ms depolarization steps from −100 to 60 mV in increments of 10 mV (top left). Dashed line represents the zero current value. Horizontal and vertical bars of 25 ms and 2 μA represent the time and current scale for all recordings. (B), Relative current vs. concentration of 5Me3F4AP curves assessed at 40 mV and (C), vs. voltage curves at different pH values. Continuous lines of panels B and C represent the fits with the Hill equation and Woodhull model (Equation 1), respectively. Fit parameters are given in Table 3.

Figure 2. Competitive inhibition of CYP2E1.

(Left) Relative fluorescence-time curves based on the 60-minute kinetic measurement of 4AP (cyan), 5Me3F4AP (green), 3F4AP (yellow), and tranylcypromine (red, positive control). (Right) fit curves for 4AP, 5Me3F4AP, 3F4AP, and tranylcypromine with the same color sets.

Table 3.

values of 5Me3F4AP: Hill and Woodhull parameters.

| Hill parameters | Woodhull parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | pH | (95% C.I.) (in μM) | IC50 (at V=0) ± s.d. (in μM) | δ ± s.d. | n |

| 5Me3F4AP | 6.4 | 220 (190–251) | 118 ± 17 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 4 |

| 7.4 | 301 (261–341) | 161 ± 25 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 6 | |

| 9.1 | 693 (523–863) | 373 ± 84 | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 5 | |

| 4AP | 6.8 | 295 (224–366) | 178 ± 5 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 4 |

| 7.4 a | 293 (258–328) | 155 ± 12 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 6 | |

| 9.1 | 65 (59–70) | 33 ± 1 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 4 | |

| 3F4AP | 6.8 | 122 (117–128) | 65 ± 3 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| 7.4 a | 244 (185–303) | 122 ± 4 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 5 | |

| 9.1 | 370 (323–417) | 159 ± 14 | 0.52 ± 0.02 | 4 | |

| 3Me4AP | 6.8 | 66 (58–75) | 44 ± 1 | 0.28 ± 0.10 | 6 |

| 7.4 a | 40 (36–43) | 21 ± 1 | 0.43 ± 0.10 | 4 | |

| 9.1 | 22 (19–24) | 10 ± 1 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 5 | |

values were determined at 40mV. A Hill parameter of h≈1 was obtained during the fitting of the data for all experimental conditions.

Data at this pH condition has been reported previously (Rodriguez-Rangel et al., 2020).

Metabolic stability towards CYP2E1 of 5Me3F4AP.

To estimate the metabolic stability of 5Me3F4AP towards CYP2E1, we conducted an in vitro investigation utilizing a competitive inhibition assay. The protocol used for this study followed a previously established method (Marks et al., 2002). According to the principle of this assay outlined in the method section, compounds that are good substrates of CYP2E1 result in greater reduction in the rate of formation of a fluorescent reporter than compounds that are poor substrates. In this study, we measured the reaction rates without competitor (blank) as well as in the presence of tranylcypromine (positive control), 4AP, 3F4AP and 5Me3F4AP. As illustrated in Figure 2, the addition of tranylcypromine, a widely recognized potent substrate of CYP2E1, resulted in the most pronounced reduction in fluorogenic emission when compared to the reaction conducted without any addition of enzyme substrates (red vs. blue lines). In comparison, 4AP exhibited a minor reduction in fluorogenic emission (cyan vs. blue lines) indicating that it is a poor substrate of CYP2E1. 3F4AP demonstrated a substantial decrease in rate (yellow vs. blue lines) indicating 3F4AP is a good substrate of CYP2E1, undergoing metabolism at a much faster rate than 4AP. In comparison, 5Me3F4AP demonstrated a reaction rate between 4AP and 3F4AP, bearing a higher resemblance to 3F4AP (Figure 2. green vs. cyan and yellow lines). To further quantify the inhibition potency of 5Me3F4AP towards CYP2E1, we measured the CYP2E1-mediated reaction rate in the presence of varying concentrations of 5Me3F4AP and 3F4AP and performed the dose-response fitting. We also compared these results with our previous results for 4AP, 3F4AP and the positive control tranylcypromine (Sun et al., 2023). This analysis showed that 5Me3F4AP has an about two times higher than 3F4AP and about 23 times lower than 4AP (Table 4, entries 1 to 3), indicating that it is more stable than 3F4AP but not as stable as 4AP.

Table 4.

values and their respective confidence interval (C.I.) for CYP2E1 substrates.

| Entry | Drug | (μM) | 95% C.I. (μM) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5Me3F4AP | 35.9 | 26.2–45.9 | 3 |

| 2 | 4APa | 831 | 605–1199 | 3 |

| 3 | 3F4AP | 17.0 | 13.9–25.2 | 6 |

| 4 | Tranylcyprominea | 2.3 | 1.5–3.4 | 3 |

Previously reported data (Sun et al., 2023).

DISCUSSION

This study identified 5Me3F4AP as novel K+ channel blocker with potential application for PET and examined critical pharmacological properties including lipophilicity, basicity, membrane permeability, target binding affinity and metabolic stability. In comparison to its predecessor 3F4AP, 5Me3F4AP was found to have higher lipophilicity (logD of 0.66 vs. 0.41) and slightly higher basicity (pKa 7.46 vs. 7.37). The lower pKa values of 3F4AP and 5Me3F4AP compared to 4AP (pKa 9.58) indicate that these compounds exist both in the neutral and protonated form at physiological pH, which facilitates the entry into the brain since only the neutral form can cross the BBB through passive diffusion. This effect was confirmed using a membrane permeability assay which showed that 5Me3F4AP cross an artificial brain membrane approximately 3 times faster than 3F4AP. These findings suggest that 5Me3F4AP will have higher brain uptake than 3F4AP.

Regarding blocking potency, it was found that at pH 7.4 the potency of 5Me3F4AP is very similar to that of 4AP and 3F4AP. At higher pH the potency of 3F4AP and 5Me3F4AP dropped significantly but not that of 4AP supporting that only the protonated form is able to block the channel (Choquet and Korn, 1992) since 3F4AP and 5Me3F4AP exist predominantly in the neutral form at basic pH. These findings suggest that 5Me3F4AP will bind to demyelinated lesions with similar sensitivity as 3F4AP.

In terms of metabolic stability, 5Me3F4AP was found to undergo CYP2E1-mediated oxidation about two times slower than 3F4AP (Figure 2, green vs. yellow lines), which was further confirmed by calculating the (35.9 vs. 17.0). Although the oxidation rate of 5Me3F4AP was still significantly faster than 4AP (Figure 2, green vs. cyan lines), this reduction in the rate of oxidation suggest that 5Me3F4AP will have greater in vivo stability than 3F4AP. A limitation of this study is that we did not test other possible metabolic enzymes, which may play a role in vivo. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to test CYP2E1 given that prior studies strongly suggest this enzyme is primarily responsible for the metabolism of 3F4AP and 4AP (Caggiano and Blight, 2013; Brugarolas et al., 2022)) and the in vivo stability of 4AP (~70% parent fraction in plasma 24 h post oral administration (Caggiano and Blight, 2013) compared to 3F4AP (< 50% parent fraction in plasma 60 min post intravenous administration (Brugarolas et al., 2022)) is consistent with the measured CYP2E1 oxidation rates for these compounds.

In sum, the favorable characteristics of 5Me3F4AP position it as an intriguing candidate worthy of further investigation as a potential alternative to [18F]3F4AP for PET imaging.

Supplementary Material

Significance Statement.

The PET tracer [18F]3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine ([18F]3F4AP) binds to K+ channels in demyelinated axons and has shown promise for imaging demyelinated lesions in animal models. However, its use in humans may be compromised due to rapid metabolism. Thus, a novel 3F4AP derivative amenable to labeling with fluorine-18 was designed and evaluated in vitro. The results indicate that 5-methyl-3F4AP exhibits high binding affinity, good physicochemical properties and slower oxidation by CYP2E1 than 3F4AP, making it a promising candidate for further PET studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01NS114066 (P.B.); PROSNI-UdeG 2022, Mexico (J.E.S.R.) and CONAHCyT, Mexico (886951) (S.R.R.).

Abbreviations:

- 4AP

4-aminopyridine

- AUC

area under curve

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CI95

95% of confidence interval

- COVC

Cut-Open Voltage Clamp

- CYP2E1

cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(ß-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid

- 3F4AP

3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethyl-piperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrometry

- IC50,

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- 5Me3F4AP

3-fluoro-5-methylpyridin-4-amine

- MES

2(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NMDG

N-methyl-D-glucamine

- 3OH4AP

3-hydroxy-4-aminopyridine

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PPF

percent of parent fraction

- RFUs

relative fluorescence units

- s.d.

standard deviation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

PB has a financial interest in Fuzionaire Diagnostics and the University of Chicago. PB is a named inventor on patents related to [18F]3F4AP owned by the University of Chicago and licensed to Fuzionaire Diagnostics. Dr. Brugarolas’ interests were reviewed and are managed by MGH and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies. A provisional patent application related to 5Me3F4AP has been filed. PB, JESR, YS and SRR are listed as inventors on this provisional patent. The other authors declare no conflict of interests.

Section: Drug Discovery and Translational Medicine

References

- Arroyo EJ, Sirkowski EE, Chitale R and Scherer SS (2004) Acute demyelination disrupts the molecular organization of peripheral nervous system nodes. The Journal of comparative neurology 479:424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basuli F, Zhang X, Brugarolas P, Reich DS and Swenson RE (2018) An efficient new method for the synthesis of 3-[18F]fluoro-4-aminopyridine via Yamada-Curtius rearrangement. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm 61:112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SG, Waser PG and Hofmann A (1989) Effects of new 4-aminopyridine derivatives on neuromuscular transmission and on smooth muscle contractility. Arzneimittelforschung 39:762–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock H, Sears TA and Sherratt RM (1981) The effects of 4-aminopyridine and tetraethylammonium ions on normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibres. J Physiol 313:301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas P, Freifelder R, Cheng S-H and Dejesus O (2016) Synthesis of meta-substituted [18F]3-fluoro-4-aminopyridine via direct radiofluorination of pyridine N-oxides. Chem Commun 52:7150–7152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas P, Reich DS and Popko B (2018a) Detecting Demyelination by PET: The Lesion as Imaging Target. Mol Imaging 17:1536012118785471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas P, Sanchez-Rodriguez JE, Tsai HM, Basuli F, Cheng SH, Zhang X, Caprariello AV, Lacroix JJ, Freifelder R, Murali D, DeJesus O, Miller RH, Swenson RE, Chen CT, Herscovitch P, Reich DS, Bezanilla F and Popko B (2018b) Development of a PET radioligand for potassium channels to image CNS demyelination. Sci Rep 8:607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas P, Wilks MQ, Noel J, Kaiser J-A, Vesper DR, Ramos-Torres KM, Guehl NJ, Macdonald-Soccorso MT, Sun Y, Rice PA, Yokell DL, Lim R, Normandin MD and El Fakhri G (2022) Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the demyelination tracer [18F]3F4AP. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 50:344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero NA, Meléndez FJ, Niño A and Muñoz-Caro C (2007) Molecular docking study of the binding of aminopyridines within the K+ channel. J Mol Model 13:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano A and Blight A (2013) Identification of metabolites of dalfampridine (4-aminopyridine) in human subjects and reaction phenotyping of relevant cytochrome P450 pathways. J Drug Assess 2:117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet D and Korn H (1992) Mechanism of 4-aminopyridine action on voltage-gated potassium channels in lymphocytes. J Gen Physiol 99:217–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux J, Gola M, Jacquet G and Crest M (2002) Effects of K+ Channel Blockers on Developing Rat Myelinated CNS Axons: Identification of Four Types of K+Channels. J Neurophysiol 87:1376–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehlings MG and Nashmi R (1996) Changes in pharmacological sensitivity of the spinal cord to potassium channel blockers following acute spinal cord injury. Brain Res 736:135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AD, Brown TR, Krupp LB, Schapiro RT, Schwid SR, Cohen R, Marinucci LN and Blight AR (2009) Sustained-release oral fampridine in multiple sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 373:732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva I, García-Pérez A, Díaz J, Aguilar S, Mino D, Santiago-Rodríguez E, Guizar-Sahagún G, Castañeda-Hernández G, Maldonado-Julián H and Madrazo I (2010) High Doses of 4-Aminopyridine Improve Functionality in Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury Patients with MRI Evidence of Cord Continuity. Arch Med Res 41:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva I, Guízar-Sahagún G, Castaneda-Hernández G, Mino D, Maldonado-Julián H, Vidal-Cantú G, Ibarra A, Serra O, Salgado-Ceballos H and Arenas-Hernández R (2003) Efficacy and Safety of 4-Aminopyridine in Patients with Long-Term Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pharmacotherapy 23:823–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guehl N, Sun Y, Russo A, Ramos-Torres K, Dhaynaut M, Klawiter E, El Fakhri G, Normandin M and Brugarolas P (2022) First-in-human brain imaging with [18F]3F4AP, a PET tracer developed for imaging demyelination. J Nucl Med 63(Sup. 2):2485. Conference Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Guehl NJ, Neelamegam R, Zhou YP, Moon SH, Dhaynaut M, El Fakhri G, Normandin MD and Brugarolas P (2021a) Radiochemical Synthesis and Evaluation in Non-Human Primates of 3-[11C]methoxy-4-aminopyridine: A Novel PET Tracer for Imaging Potassium Channels in the CNS. ACS Chem Neurosci 12:756–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guehl NJ, Ramos-Torres KM, Linnman C, Moon SH, Dhaynaut M, Wilks MQ, Han PK, Ma C, Neelamegam R, Zhou YP, Popko B, Correia JA, Reich DS, Fakhri GE, Herscovitch P, Normandin MD and Brugarolas P (2021b) Evaluation of the potassium channel tracer [18F]3F4AP in rhesus macaques. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 41:1721–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes KC (2006) The Use of 4-Aminopyridine (Fampridine) in Demyelinating Disorders. CNS Drug Rev 10:295–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes KC, Blight AR, Potter PJ, Allatt RD, Hsieh JTC, Wolfe DL, Lam S and Hamilton JT (1993) Preclinical trial of 4-aminopyridine in patients with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 31:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen HB, Ravnborg M, Dalgas U and Stenager E (2014) 4-Aminopyridine for symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 7:97–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Eftekharpour E and Fehlings MG (2004) Temporal and spatial patterns of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 protein and gene expression in spinal cord white matter after acute and chronic spinal cord injury in rats: implications for axonal pathophysiology after neurotrauma. The European journal of neuroscience 19:577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch GE and Narahashi T (1978) 3,4-diaminopyridine. A potent new potassium channel blocker. Biophys J 22:507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch GE, Shieh CC, Drewe JA, Vener DF and Brownt AM (1993) Segmental exchanges define 4-aminopyridine binding and the inner mouth of K+ pores. Neuron 11:503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks BD, Smith RW, Braun HA, Goossens TAC, Marie; and Ozers MSL, Connie S. ; Trubetskoy Olga V. (2002) A High Throughput Screening Assay to Screen for CYP2E1 Metabolism and Inhibition Using a Fluorogenic Vivid® P450 Substrate. Assay Drug Dev Technol 1:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashmi R and Fehlings MG (2001) Mechanisms of axonal dysfunction after spinal cord injury: with an emphasis on the role of voltage-gated potassium channels. Brain Res Rev 38:165–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike VW (2009) PET radiotracers: crossing the blood–brain barrier and surviving metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci 30:431–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radomski KL, Zi X, Lischka FW, Noble MD, Galdzicki Z and Armstrong RC (2022) Acute axon damage and demyelination are mitigated by 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) therapy after experimental traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 10:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Torres K, Sun Y, Takahashi K, Zhou Y-P and Brugarolas P (2022) Evaluation of anesthesia effects on the brain uptake and metabolism of demyelination tracer [18F]3F4AP. J Nucl Med 63(Sup. 2): 2956. Conference Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Torres KM, Zhou YP, Yang BY, Guehl NJ, Sung-Hyun M, Telu S, Normandin MD, Pike VW and Brugarolas P (2020) Syntheses of [11C]2- and [11C]3-trifluoromethyl-4-aminopyridine: potential PET radioligands for demyelinating diseases. RSC Med Chem 11:1161–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Trimmer JS, Schwarz TL, Levinson SR, Ellisman MH, Schachner M and Shrager P (1998) Potassium channel distribution, clustering, and function in remyelinating rat axons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 18:36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rangel S, Bravin AD, Ramos-Torres KM, Brugarolas P and Sanchez-Rodriguez JE (2020) Structure-activity relationship studies of four novel 4-aminopyridine K+ channel blockers. Sci Rep 10:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal JL, Pathak MS, Hernandez JP, Himber PL, Brunnemann SR and Charter RS (1999) Safety and Efficacy of 4-Aminopyridine in Humans with Spinal Cord Injury: A Long-Term, Controlled Trial. Pharmacotherapy 19:713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherratt RM, Bostock H and Sears TA (1980) Effects of 4-aminopyridine on normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibres. Nature 283:570–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha K, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Velumian AA and Fehlings MG (2006) Functional changes in genetically dysmyelinated spinal cord axons of shiverer mice: role of juxtaparanodal Kv1 family K+ channels. Journal of neurophysiology 95:1683–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefoski D, Davis FA, Faut M and Schauf CL (1987) 4-Aminopyridine improves clinical signs in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 21:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Smith D, Fu Y, Cheng J-X, Bryn S, Borgens R and Shi R (2009) Novel Potassium Channel Blocker, 4-AP-3-MeOH, Inhibits Fast Potassium Channels and Restores Axonal Conduction in Injured Guinea Pig Spinal Cord White Matter. J Neurophysiol 103:469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Guehl NJ, Zhou Y-P, Takahashi K, Belov V, Dhaynaut M, Moon S-H, El Fakhri G, Normandin MD and Brugarolas P (2022) Radiochemical Synthesis and Evaluation of 3-[11C]Methyl-4-aminopyridine in Rodents and Nonhuman Primates for Imaging Potassium Channels in the CNS. ACS Chem Neurosci 13:3342–3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Ramos-Torres K and Brugarolas P (2023) Metabolic Stability of the Demyelination PET Tracer [18F]3F4AP and Identification of its Metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 386(1):93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DL, Hayes KC, Hsieh JTC and Potter PJ (2001) Effects of 4-Aminopyridine on Motor Evoked Potentials in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. J Neurotrauma 18:757–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhull AM (1973) Ionic Blockage of Sodium Channels in Nerve. J Gen Physiol 61:687–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.