Abstract

Opioid misuse (OM) is a priority public health concern, especially for those in correctional settings. Understanding the etiology of OM among justice-involved children (JIC) is key to resolving this crisis. On average, 12% of all children and up to 50% of JIC in the United States have experienced household substance misuse (HSM). Theory and empirical research suggest that HSM may increase risk for OM, but these relationships have not been examined among JIC. The objective of this study was to examine the effects of sibling and parent substance misuse on OM among JIC. Cross-sectional data on 79,960 JIC from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ) were examined. Past 30-day opioid (P30D) OM was indicated by urine analysis. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed. In the total sample, nearly 3% met FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM and nearly 25% lived with a parent/caregiver or sibling who misused substances. Among opioid misusers, one third lived with a parent/caregiver who misused substances and nearly half lived with a parent/caregiver or sibling who misused substances. Compared to JIC without HSM, JIC reporting sibling substance misuse had 1.95 times higher odds of OM (95% CI, 1.63–2.33), JIC with parent substance misuse had over twice the odds of OM (95% CI, 1.89–2.31), and those with both sibling and parent had more than three times higher odds of OM (95% CI, 2.75–3.87). Family-based approaches to OM intervention and prevention initiatives may be more effective than individual-focused approaches. Implications are discussed.

Keywords: Opioid misuse, Household substance use, Juvenile justice, Family history, Adolescence

Introduction

For many adolescents in the United States (U.S.), the correctional system has become the de facto drug treatment center. The opioid misuse (OM) epidemic has accelerated this trend (O’Donnell et al., 2017). OM refers to consuming prescription opioids non-medically or using illicit opioids such as heroin (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). The recent shift from prescription opioids to heroin and other illicit opioids has resulted in more users entering the criminal justice system (O’Donnell et al., 2017). Opioid overdose is among the leading causes of death among justice-involved populations (Binswanger et al., 2013). Prevention and intervention efforts require a deeper understanding of the predictors of OM initiation among correctional populations. For example, a recent study found that reducing OM among incarcerated adults can reduce overall statewide rates of opioid overdose fatalities (Green et al., 2018). This beneficial effect on adults suggests that attention to those in the juvenile justice system is warranted, referred to herein as justice-involved children (JIC). Compared to those who have never been involved in the justice system, JIC have a higher prevalence of substance misuse, substance use disorders (Belenko et al., 2017; Johnson & Tran, 2020), and exposure to substance misuse in their homes (Baglivio et al., 2014). Experiencing household substance misuse may be a strong predictor of OM initiation among JIC, and a promising target for OM prevention.

Household substance misuse (HSM) is defined as having a sibling or parent/caregiver in the household who suffers from substance misuse. HSM is recognized as a significant type of childhood adversity. It is one of the items that comprised the renowned Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) score (Shin et al., 2017). Research has shown that ACEs are factors that can predict poor health outcomes (Baglivio & Epps, 2016; Felitti et al., 1998; Tilson, 2018). HSM is one of many factors in the ACEs measure that are associated with poor health outcomes, including substance misuse (Wolff et al., 2018). Although much is known about intergenerational misuse of some drugs, such as alcohol, there is a paucity of research on the relationship between HSM and OM among adolescents (Peisch et al., 2018). The existing research has not yet examined the link between HSM and OM among JIC.

Theory and empirical research on adolescents in the general population provide substantial evidence that suggests when children are exposed to substance misuse in their own homes they are more prone to misuse substances themselves (Nadel & Thornberry, 2017; Whiteman et al., 2013). There are several conceptual models that explain the association between HSM and adolescent OM including genetic, social structure and, commonly, social learning theories (Ashrafioun et al., 2011; Kendler et al., 2014; Krohn et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2004; McCutcheon et al., 2013; Nicholson et al., 2016; Rudolph et al., 2011).

Akers (2009) combined the criminological theory of differential association with the principles of operant conditioning to develop one of the key advances in social learning theory that focuses specifically on risk behaviors, such as substance misuse. Akers posits that substance misuse, and all other behaviors, is learned through four major constructs of social learning theory: differential association, definitions, imitation, and differential reinforcement. Differential association, the most important of these constructs, refers to the people with whom the individual is more likely to interact with and more closely connected. In the context of OM, it proposes that through interactions, individuals learn the values, attitudes, techniques, and motives for substance misuse.

According to differential association, an individual’s peers, relatives and community members may increase or decrease the likelihood of OM through their actions and attitudes towards substance misuse. Differential association also impacts the other domains of social learning theory, including definitions, imitation, and differential reinforcement. It defines the context by which individuals may a) observe others engaging in substance misuse, which relates to imitation, b) receive incentives for OM, and c) adopt favorable definitions or perceptions toward OM. Most of the evidence in support of social learning has been in support of differential association through testing the influence of delinquent peers on substance misuse (Brooks et al., 2012; Krohn et al., 2016; Pratt et al., 2010). While families and individuals are both influenced by neighborhoods, communities and the broader society, differential association addresses the variation in risk for substance misuse among adolescents in the same or similar neighbors and communities. The differential association model has not yet been directly leveraged to test the effects of differential association with siblings or parents who engage in substance misuse on risk for OM: however, there is consensus that parent and sibling substance misuse is linked to a child’s substance misuse initiation through interconnected biological and psychosocial mechanisms (Krohn et al., 2016; Nadel & Thornberry, 2017).

The preponderance of extant empirical evidence has found intergenerational patterns of substance misuse (Braitman et al., 2009; Johnson & Leff, 1999; Krohn et al., 2016; Nadel & Thornberry, 2017; Peisch et al., 2018). Based on data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, Austin and Shanahan (2017) found that opioid use was more prevalent among parents than non-parents. A considerable number of all children (Lipari & Horn, 2017) and up to 50% of certain JIC lived in families with a parent and/or sibling who misused substances (Johnson, 2018; Levenson, 2016). Parental substance misuse can have adverse effects on their children that increase their risk of OM. Ashrafioun and colleagues (2011) found that parental OM was associated with higher Brief Impairment Scale scores among their children, indicating that these youth have more risk factors for OM and more severe forms of substance misuse.

However, there are very few rigorously conducted studies examining children of parents who misuse opioids (Peisch et al., 2018). Children adopt similar substance misuse patterns of not only their parents, but also their siblings (Kendler et al., 2014; McCutcheon et al., 2013; Whiteman et al., 2013). Whiteman, Jensen, and Maggs (2013) found that older siblings’ alcohol and other substance use was positively associated with younger siblings’ patterns of use while controlling for parents’ and peers’ use. These studies indicate that the research on the etiology of OM may be improved by investigating the individual and combined effects of sibling and parent substance misuse.

Though prior research provided critical insights into intergenerational and sibling-to-sibling substance misuse, several key questions remain unanswered. Certain substance types, such as opioids, are a high-priority public health concern. Though the consequences of OM among JIC can be devastating, there is scarce research on the prevalence and predictors of OM among JIC. Data indicates that JIC have a higher prevalence of experiencing HSM (Johnson, 2017b; Levenson, 2016), substance misuse and substance use disorder (Johnson & Cottler, 2020), and other risk factors that are linked to OM (Baglivio et al., 2014). However, there is no existing research on the association between HSM and OM among JIC.

Based on the model of differential association, this study makes three hypotheses: JIC who lived with siblings who misused substances will have higher odds of OM than JIC who did not experience HSM; JIC with a parent who misused substances will have higher odds of OM than JIC who did not experience HSM; and JIC with both a sibling and parent/caregiver who misused substances will have higher odds of OM compared to both a) JIC with only a sibling or only parent who misused substances and b) JIC who did not experience HSM.

To test these hypotheses, the study leveraged statewide data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ)-the third largest juvenile justice population in the U.S. The study adjusted for sociodemographic covariates: gender, race, family income, and age. Prior research has shown that female gender, non-Latino white race, higher household incomes, and young JIC were significantly associated with higher risk of OM (Egan et al., 2019; Johnson & Cottler, 2020; Serdarevic et al., 2017; Shaw et al., 2019). These sociodemographic factors must be considered to achieve accurate estimates of the effects of HSM on OM.

Methods

Participants

The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ) is a state agency of Florida that manages juvenile justice and operates juvenile detention centers. Since 2007, FLDJJ has collected data on all youth who are arrested using a comprehensive assessment and case management process. When a minor is arrested in Florida, they complete an enrollment process to enter the FLDJJ system. As a part of the enrollment process, all youth are administered the Positive Achievement Change Tool (PACT) assessment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida and the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. The study examined an existing de-identified database. The study did not involve new data collection with human participants; therefore, informed consent was not applicable.

Procedure

The PACT instrument has been validated across multiple samples of FLDJJ data published in several peer-reviewed journals (see Baglivio & Jackowski, 2013). Trained personnel conducted semi-structured interviews using the PACT software. The interface guided all aspects of data collection; it included open-ended questions, an interview guide, the PACT manual and coding techniques. This report included 80,441 JIC in the FLDJJ PACT dataset. Less than 1% (n = 481) of the total cases were omitted due to missing data on substance misuse, resulting in a final dataset of 79,960 JIC.

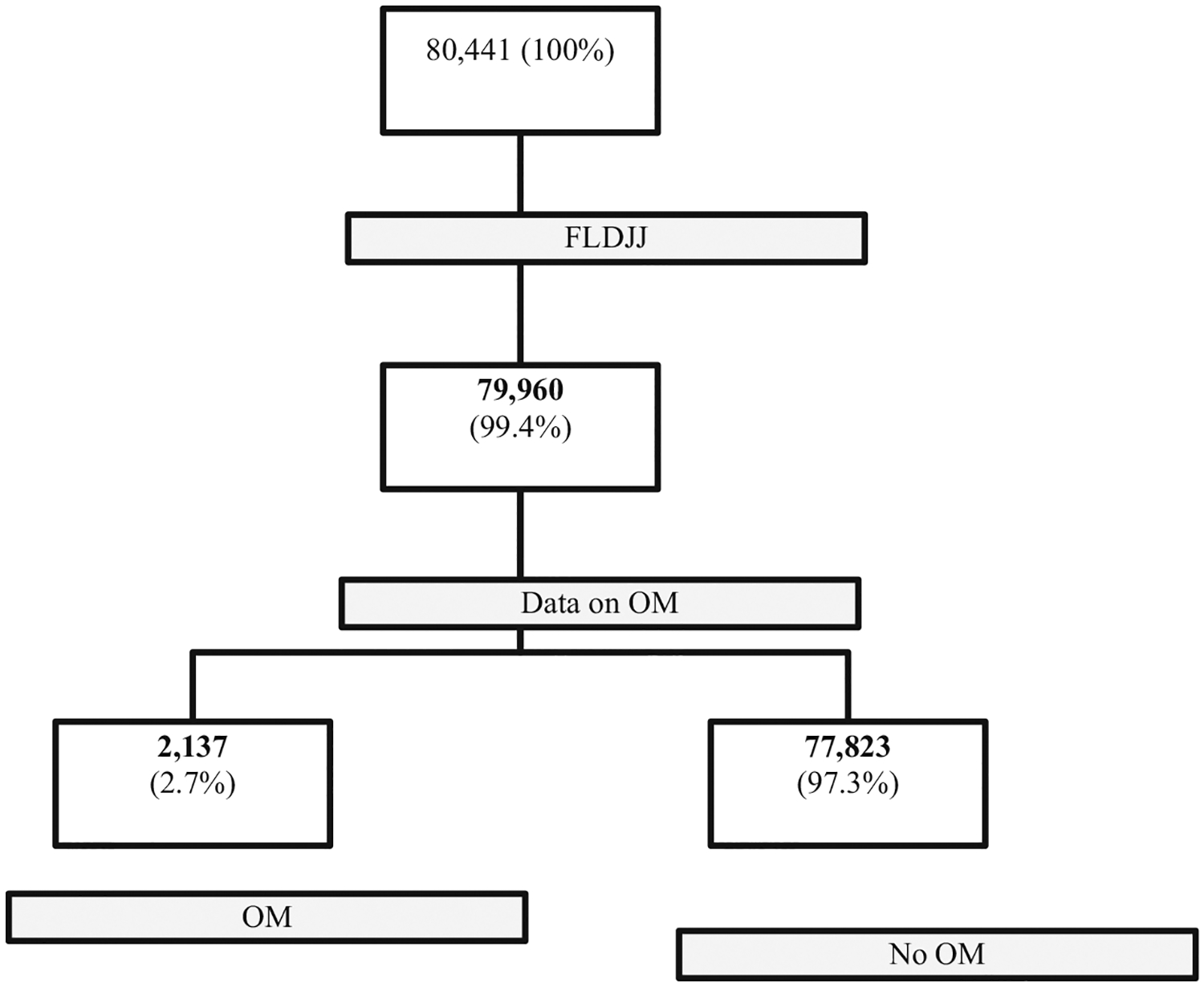

The sample represented all youth who entered the FLDJJ from 2007 to 2015, completed the PACT assessment, reached the age of 18 by year 2015, and had data on the current OM question. Nearly 38.3% were non-Latinx White (n = 30,591), 45.6% of subjects were non-Latinx Black or African American (n = 36,443), 15.7% were Latinx (n = 12,536), and 0.5% were another race (n = 390). Roughly 21.9% of the sample were females (n = 17,497) and the mode age at intake was 13–14. See Fig. 1 for a flow diagram of the sample.

Fig. 1.

Flow Diagram of FLDJJ Data. Note. <1% (n = 481) of 80,441 particpants were omitted due to missing data on opioid misuse (OM)

Measures

Opioid misuse

The construct current opioid misuse, abbreviated as OM, referred to using non-medical prescription opioids or illicit opioids. OM was operationalized by FLDJJ criteria: urinalysis indicating illicit or non-medical opioid consumption within the past 30 days, abbreviated P30D OM, at the final screen. The types of opioids included heroin and other opioids such as Dilaudid, Demerol, Percodan, Codeine, Oxycontin, etc. Responses were coded into a dichotomous measure that reported whether or not the youth met the FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM. The response items were (0) no, did not meet FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM” or (1) yes, P30D OM as indicated by urine analysis.

Household substance misuse

The construct household substance misuse (HSM) was operationalized by a four-item categorical measure of lifetime HSM that included substance misuse by parents and/or siblings. An individual would be defined as having a history of HSM if there was evidence or admission of parental alcohol problems, parental drug problems, sibling alcohol problems, and or sibling drug problems. The response items were (0) no household substance misuse, (1) sibling substance misuse, (2) parent or caregiver substance misuse, and (3) both sibling and parent/caregiver substance misuse. This data was derived from FLDJJ records of urine analysis or self-reported by the juvenile or the parent/guardian. Data on the source of the drug for parents and siblings in the house was not provided.

Control variables

The study adjusted for known predictors of OM (gender, race, age, family income). Gender was operationalized by a self-reported measure (0 = male gender, 1 = female gender). Race is a social construct that commonly includes or is used synonymously with ethnicity and national origin. Therefore, race was used to refer to race and ethnicity. Race was operationalized by a four-item nominal measure (0 = White, 1 = Black, 2 = Latinx, 3 = other). This variable was used to create three dummy variables, Blacks, Latinx and Other, with Whites serving as the reference category, coded 0. The dummy variables were created using Stata “i” commands. Age was based on Date of Birth at the intake assessment. It was reported in the dataset as a five-item ordinal variable (0 = 12 and under, 1 = 13 to 14, 2 = 15, 3 = 16 and 4 = over 16). Family income was measured by a four-item ordinal variable reporting the combined annual income of the youth and family. Response options were (0) under $15,000, (1) from $15,000 to $34,999, (2) from $35,000 to $49,999, and (3) $50,000 and above.

Data Analyses

Data analysis was conducted using STATA, version 15 SE (StataCorp, 2017). A complete case analysis was appropriate given that there was minimal missing data (<1%) that was Missing Completely at Random and the sample size was over 79,000. Demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. The criteria for statistical significance was p < 0.05. A chi-square test of independence was performed to compare whether there was a significant association between categorical variables and OM. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals. The covariates of gender, race, age, and family income were controlled in the multivariate model. OM was a limited dependent variable, therefore the Firth approach was employed to adjust for the error caused by rare events (Coveney, 2008). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to confirm adequate model fit.

Results

Univariate Analyses

The univariate analysis described the total sample of 79,960 JIC in the FLDJJ dataset. Approximately 2.7% met the FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM and nearly 25% reported HSM. Over 60% of the sample were a non-White race or ethnicity. More than 52% reported a household income range between $15,000 and $34,999. The mode age of P30D users in the sample was 13–14 years of age.

Bivariate Analyses

HSM was more prevalent among JIC who met the criteria for P30D OM when compared to the non-P30D OM group (See Table 1). There were more females in the P30D OM group than the non-P30D OM group (31.8% versus 21.6%). There were also considerably more Whites in the P30D OM group (80.6%) than Whites in the non-P30D OM group (37.1%) and considerably fewer Blacks in the P30D OM group (8.3%) compared to Blacks in the non-P30D OM group (46.6%). In addition, compared to the non-P30D OM group, those who met criteria for P30D OM had higher household incomes (11.9% versus 6.8% reporting $50,000 or more). See Table 1 for complete descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample by opioid misuse

| Total | No P30D OM | P30D OM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household substance misuse | |||

| None | 75.6 | 76.2 | 52.4 |

| Sibling | 4.7 | 4.7 | 6.7 |

| Parent | 16.8 | 16.3 | 32.6 |

| Sibling and parent | 2.9 | 2.8 | 8.3 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 78.1 | 78.4 | 68.2 |

| Female | 21.9 | 21.6 | 31.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 38.3 | 37.1 | 80.6 |

| Black | 45.6 | 46.6 | 8.3 |

| Latinx | 15.7 | 15.8 | 10.2 |

| other | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Age | |||

| 12 and under | 24.5 | 24.6 | 19.0 |

| 13–14 | 36.3 | 36.3 | 38.5 |

| 15 | 18 | 17.9 | 20.5 |

| 16 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 14.4 |

| Over 16 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.5 |

| Income | |||

| Under $15,000 | 25.9 | 26.0 | 21.9 |

| From $15,000 to $34,999 | 52.4 | 52.5 | 47.7 |

| From $35,000 to $49,999 | 14.8 | 14.7 | 18.6 |

| $50,000 and over | 6.9 | 6.8 | 11.9 |

Multivariate Analyses

Table 2 displayed the results of the multivariate logistic regression model estimating the odds of P30D OM. The model controlled for gender, race, age, and household income. Compared to JIC who did not experience HSM, JIC who had a sibling who misused substances had 1.95 times the odds of meeting criteria for P30D OM (aOR: 1.95; 95% CI 1.63, 2.33), those who had a parent who misused substances had over twice the odds of P30D OM (aOR: 2.09; 95% CI 1.89, 2.31), and those who had both a sibling and parent who misused substances had 3.3 times higher odds of P30D OM (aOR: 3.26; 95% CI 2.75, 3.87). Figure 2 displayed the adjusted odds ratios of HSM.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Estimating P30D Opioid Misuse

| aOR | CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Household Substance Misuse (Ref = None) | ||

| Sibling | 1.95 | [1.63, 2.33] |

| Parent | 2.09 | [1.89, 2.31] |

| Sibling and Parent | 3.26 | [2.75, 3.87] |

| Gender (Ref = Males) | ||

| Females | 1.49 | [1.36, 1.64] |

| Race/ethnicity (Ref = White) | ||

| Black | 0.10 | [0.08, 0.11] |

| Latinx | 0.36 | [0.31, 0.41] |

| Other | 0.95 | [0.59, 1.51] |

| Age (Ref = 12 and under) | ||

| 13–14 | 1.23 | [1.09, 1.39] |

| 15 | 1.30 | [1.13, 1.50] |

| 16 | 1.19 | [1.02, 1.39] |

| Over 16 | 1.11 | [0.92, 1.35] |

| Income (Ref = Under $15,000) | ||

| From $15,000 to $34,999 | 1.00 | [0.89, 1.12] |

| From $35,000 to $49,999 | 1.06 | [0.92, 1.22] |

| $50,000 and over | 1.25 | [1.07, 1.48] |

| Constant | 0.03 | [0.03, 0.04] |

| Observations | 79,960 |

Note. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in brackets

Fig. 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of past 30-day opioid misuse

Certain sociodemographic factors were also associated with P30D OM. Females had 1.49 times the odds of misusing opioids as males (aOR: 1.49; 95% CI 1.36, 1.64). Compared to Whites, Blacks had 90% lower odds (aOR: 0.10; 95% CI 0.08, 0.11) and Latinx had 64% lower odds (aOR: 0.36; 95% CI 0.31, 0.41), which translated into Whites having 2.8 times higher odds of P30D OM as Latinx, and over 10 times higher odds as Blacks. JIC who were in the $50,000 and over household income bracket had 25% higher odds of P30D OM than those in the under $15,000 income bracket (aOR: 1.25; 95% CI 0.03, 0.04). The FLDJJ data can be accessed by request from the FLDJJ. These findings can be reproduced using standard logistic regression procedures.

Discussion

Nearly 3% of the sample met the FLDJJ criteria for P30D OM, which is relatively consistent with rates of OM observed in national studies of adolescents and adults (SAMHSA, 2019). However, in context, this statistic is concerning given that the mode age of P30D OM users in the sample was 13 to 14 years of age. An early onset of justice involvement and OM initiation are associated with severe and lasting adverse health outcomes. Therefore, further scientific attention is needed to understand the health needs of these populations. The study found support for the basic principle of differential association theory. Parents and siblings have major influence on children and adolescents, especially among disadvantaged populations who may lack access to prosocial role models.

Sibling Substance Misuse

The first hypothesis was supported by evidence indicating that having a sibling who misused substances was associated with nearly twice the odds of OM. These findings align with previous evidence demonstrating that sibling substance misuse increases risk for substance misuse (Snyder & Howard, 2015; Whiteman et al., 2014; Whiteman et al., 2013). Whiteman and colleagues (2014) found that sibling admiration and mutual modeling was strongly linked to sibling similarities in substance misuse. Because up to 90% of JIC experience parental separation or divorce (Johnson, 2017a), sibling influence may be heighten among these populations. In addition to sibling influence, continuity of substance misuse among siblings may be linked to common social contexts, such as shared friends and shared parental characteristics (Snyder & Howard, 2015; Whiteman et al., 2014).

Parental Substance Misuse

One third of current opioid misusers had a parent who misused substances. The second hypothesis was supported by evidence indicating that having a parent who misused substances was associated with more than twice the odds of OM as having a parent who did not misuse substances. These findings were corroborated by a substantial body of research uncovering intergenerational substance misuse problems (Braitman et al., 2009; Krohn et al., 2016; Nadel & Thornberry, 2017; Peisch et al., 2018). Parents have strong potential to influence their children, whether toward positive or negative outcomes. The high prevalence of parental substance misuse among OM signifies that adolescent OM may be partly rooted in family dynamics.

Sibling and Parental Substance Misuse

Nearly half of those who misused opioids in the past 30 days lived with a parent or a sibling who misused substances. Over 8% of JIC lived in a household where both a sibling and parent suffered from substance misuse. The third hypothesis was supported by evidence showing that living in a household where both a sibling and parent misused substances was associated with more than three times the odds of OM than living in a household without any substance misuse. This is a relatively rare, but extremely problematic circumstance. Prevention and intervention efforts may benefit from household-level approaches rather than individual-level strategies.

Family-centered approaches to substance misuse prevention and treatment may be critical, given the huge influence that parents and siblings have. While family and individual substance misuse patterns are influenced by macro level factors such as drug supply, healthcare, unemployment, and other social dynamics, addressing these issues are beyond the capacity of the juvenile justice system. However, the juvenile justice system has the capacity to divert children and adolescents to substance misuse treatment services and integrate family-centered programs. This study provided some support for family-based therapies among JIC such as Functional Family Therapy, Multisystemic Therapy®, and others. Functional Family Therapy is a short-term family therapy intervention and juvenile diversion program helping at-risk children and JIC to overcome substance misuse (Lee et al., 2011). Multisystemic Therapy® is a juvenile crime prevention program designed to improve the real-world functioning of children and adolescents by changing their natural settings (home, school, and neighborhood) in ways that promote prosocial behavior while decreasing OM (Van der Stouwe et al., 2014). The Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14, deemed effective by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Model Programs and Crime Solutions, and Promising by Blueprints, targets family-level dynamics and has been shown to reduce adolescent substance misuse (Molgaard et al., 1996; Molgaard & Spoth, 2001). Though subject to critique, interventions such as the Strengthening Families Program that target parent and child outcomes may also be effective in preventing or reducing adolescent OM (Gorman et al., 2007).

Limitations

The study had limitations that provide context for discussing the interpretations and recommendations. The cross-sectional data limited the ability to establish either causal conclusions or the exact temporal sequence between HSM, and the outcome, OM. The study was not a test of differential association, but it provided a foundation for a more complete test of differential association in future research. The sample represented Florida JIC and the findings may not be generalizable to JIC in other populations. OM included heroin and prescription OM, which prevents an analysis of the potential differences between each opioid type. OM was a limited dependent variable, with less than three percent of youth reporting current OM. The Firth method, also called penalized likelihood, is a general approach to reducing small-sample bias in maximum likelihood estimation (Coveney, 2008). The Firth approach indicated that the limited variation was not problematic. However, datasets with a larger sample of current misusers may uncover important nuances between different forms and patterns of misuse. The data does not allow for distinction between the types of substances used by the parent and sibling, preventing an analysis of nuances among substance types. Understanding the etiology of OM can be materially enhanced by integrating the principles of social learning theory. However, social learning theory has been criticized as limited in scope –focusing on micro and meso level processes and paying less attention to structural factors that influence substance misuse outcomes. Future efforts to investigate HSM and risk for OM should build upon the current study and embrace interdisciplinary coalitions to address the aforementioned shortcomings.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the study contributed important information to the scientific literature that may assist in addressing a chief public health concern. The study leveraged a statewide sample of nearly 80,000 JIC to investigate the effects of sibling and parent substance misuse on the odds of OM among a critically underserved pediatric population. Identifying the predictors of OM initiation among correctional populations is a top priority for the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which awarded $141.3 million to the Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (NIH, 2019). The study leveraged urine analysis to operationalize OM, rather than solely relying on self-disclosure. This research embraced an interdisciplinary approach, fusing epidemiological methods and criminological theory to examine whether household family member substance misuse profiles are associated with higher risk of OM. The study may set the foundation for a complete test of differential association theory. The findings and interpretations provided valuable information to better understand JIC, adolescent OM and how family-based approaches may help prevent or reduce OM and related problems.

Future Research

Future research should build on the current study and conduct a complete test of differential association theory. Studies that examine differences among opioid types and the moderating effects of sociodemographic characteristics among justice-involved populations can advance the literature on OM among JIC. Longitudinal designs, comprehensive data and nationally representative samples are needed to test causal processes, such as the differential association model, and inform the development of intervention programs.

Conclusions

Children who have a record of delinquent behavior are already at a tremendous disadvantage. Many of them enter the system due to substance-related issues. Adolescent OM can have a disastrous impact on youth and their communities. Therefore, it is essential to uncover the factors linked to OM. Half of current opioid users had a sibling and/or parent who misused substances. JIC who resided in a household where parents and/or siblings misuse substances had 2–3 times the odds of meeting criteria of P30D OM, indicating that adolescent OM may be homegrown. These findings provide some support for family-centered prevention strategies. The Florida juvenile justice community can benefit from widely implementing programs that address family-level risk factors to prevent OM and related problems.

Highlights.

Having a sibling who misused substances was associated with nearly twice the odds of OM among JIC.

Having a parent who misused substances was associated with more than twice the odds of OM as having a parent who did not misuse substances among JIC.

JIC who resided in a household where parents and/or siblings misuse substances had 2–3 times the odds of meeting criteria of P30D OM, indicating that adolescent OM may be homegrown.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse under award numbers 1K01DA052679 (M.E.J., PI), R25DA050735 (M.E.J., PI), R25DA035163 (M.E.J., Sub-PI), U01DA051039 (M.E.J., Sub-PI), and T32DA035167 (Dr. Linda B. Cottler, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Florida, the National Institutes of Health or the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent was not required. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida and the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

References

- Akers RL (2009). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance (1st ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9781315129587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafioun L, Dambra CM, & Blondell RD (2011). Parental prescription opioid abuse and the impact on children. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(6), 532–536. 10.3109/00952990.2011.600387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin AE, & Shanahan ME (2017). Prescription opioid use among young parents in the united states: results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health. Pain Medicine, 18(12), 2361–2368. 10.1093/pm/pnw343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, & Epps N (2016). The interrelatedness of adverse childhood experiences among high-risk juvenile offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 14(3), 179–198. 10.1177/1541204014566286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Epps N, Swartz K, Huq MS, Sheer A, & Hardt NS (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhoodexperiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1–22. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/Prevalence_of_ACE.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, & Jackowski K (2013). Examining the validity of a juvenile offending risk assessment instrument across gender and race/ethnicity. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 11(1), 26–43. 10.1177/1541204012440107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Knight D, Wasserman GA, Dennis ML, Wiley T, Taxman FS, Oser C, Dembo R, Robertson AA, & Sales J (2017). The Juvenile Justice Behavioral Health Services Cascade: A new framework for measuring unmet substance use treatment services needs among adolescent offenders. Journal of Substance Abus Treatment, 74, 80–91. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, & Stern MF (2013). Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 592–600. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitman AL, Kelley ML, Ladage J, Schroeder V, Gumienny LA, Morrow JA, & Klostermann K (2009). Alcohol and drug use among college student adult children of alcoholics. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 53(1), 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks FM, Magnusson J, Spencer N, & Morgan A (2012). Adolescent multiple risk behaviour: An asset approach to the role of family, school and community. Journal of Public Health, 34(Suppl. 1), i48–i56. 10.1093/pubmed/fds001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coveney J (2008). Firthlogit: Stata module to calculate bias reduction in logistic regression. https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s456948.htm

- Egan KL, Gregory E, Osborne VL, & Cottler LB (2019). Power of the peer and parent: Gender differences, norms, and nonmedical prescription opioid use among adolescents in south central kentucky. Prevention Science, 20(5), 665–673. 10.1007/s11121-019-0982-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, & Williamson DF (1998). Adverse childhood experiences and health outcomes in adults: The ACE study. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 90(3), 31. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman DM, Conde E, & Huber JC Jr (2007). The creation of evidence in ‘evidence-based’drug prevention: a critique of the strengthening families program plus life skills training evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(6), 585–593. 10.1080/09595230701613544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Clarke J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Marshall BDL, Alexander-Scott N, Boss R, & Rich JD (2018). Post-incarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 405–407. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, & Leff M (1999). Children of substance abusers: overview of research findings. Pediatrics, 103(Suppl 2), 1085–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME (2017a). Childhood trauma and risk for suicidal distress in justice-involved children. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 80–84. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME (2017b). Trauma, race, and risk for violent felony arrests among florida juvenile offenders. Crime & Delinquency, 64(11), 1437–1457. 10.1177/0011128717718487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME (2018). The effects of traumatic experiences on academic relationships and expectations in justice-involved children. 10.1002/pits.22102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, & Cottler LB (2020). Optimism and opioid misuse among justice-involved children. Addictive Behaviors, 103, 106–226. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, & Tran DX (2020). Factors associated with substance use disorder treatemtn completion: a cross-sectional analysis of justice-involved adolescents. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(92). 10.1186/s13011-020-00332-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Maes HH, Sundquist K, Ohlsson H, & Sundquist J (2014). Genetic and family and community environmental effects on drug abuse in adolescence: a swedish national twin and sibling study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Loughran TA, Thornberry TP, Jang DW, Freeman-Gallant A, & Castro ED (2016). Explaining adolescent drug use in adjacent generations: testing the generality of theoretical explanations. Journal of Drug Issues, 46(4), 373–395. 10.1177/0022042616659758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, L Akers R, & J Borg M (2004). Social learning and structural factors in adolescent substance use. Western Criminology Review, 5(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Aos S, Drake E, Pennucci A, Miller M, & Anderson L (2011). Return on investment: Evidence-based options to improve statewide outcomes, April 2012 (Document No. 12-04-1201). Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy. http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/1102/Wsipp_Return-on-Investment-Evidence-Based-Options-to-Improve-Statewide-Outcomes-April-2012-Update_Full-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and subsequent substance abuse in a sample of sexual offenders: Implications for treatment and prevention. Victims & Offenders, 11(2), 199–224. 10.1080/15564886.2014.971478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, & Horn SLV (2017). Children living with parents who have a substance use disorder. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_3223/ShortReport-3223.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon VV, Scherrer JF, Grant JD, Xian H, Haber JR, Jacob T, & Bucholz KK (2013). Parent, sibling and peer associations with subtypes of psychiatric and substance use disorder comorbidity in offspring. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 128(1), 20–29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard VK, Kumpfer K, & Fleming E (1996). The strengthening families program: For parents and youth 10–14–revised. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Extension Service. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/sfp10-14/ [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard VK, & Spoth R (2001). The strengthening families program for young adolescents: Overview and outcomes. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 18(3), 15–29. 10.1300/J007v18n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel EL, & Thornberry TP (2017). Intergenerational consequences of adolescent substance use: patterns of homotypic and heterotypic continuity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(2), 200–211. 10.1037/adb0000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson J, Dawson-Edwards C, Higgins GE, & Walton IN (2016). The nonmedical use of pain relievers among africanamericans: A test of primary socialization theory. Journal of Substance Use. 10.3109/14659891.2015.1122101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2019). Justice community opioid innovation network. https://heal.nih.gov/research/research-topractice/jcoin.

- O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, & Seth P (2017). Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by census region—United States, 2006–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(34), 897–903. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6634a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisch V, D Sullivan A, Breslend NL, Benoit R, Sigmon SC, Forehand GL, & Forehand R (2018). Parental opioid abuse: a review of child outcomes, parenting, and parenting interventions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), 2082–2099. 10.1007/s10826-018-1061-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt TC, Cullen FT, Sellers CS, Thomas Winfree L, Madensen TD, Daigle LE, Fearn NE, & Gau JM (2010). The empirical status of social learning theory: A meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 27(6), 765–802. 10.1080/07418820903379610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AE, Jones KC, Latkin C, Crawford ND, & Fuller CM (2011). The association between parental risk behaviors during childhood and having high risk networks in adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2), 437–443. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the united states: Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health. (HHS Publication N. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). 2018 national survey on drug use and health: Methodological summary and definitions. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Serdarevic M, Striley CW, & Cottler LB (2017). Sex differences in prescription opioid use. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(4), 238–246. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DJ, Warren TB, & Johnson ME (2019). Family structure and past-30 day opioid misuse among justice-involved children. Substance Use and Misuse, 54(7), 1226–1235. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1573839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, McDonald SE, & Conley D (2017). Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and substance use among young adults: a latent class analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 187–192. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SM, & Howard MO (2015). Patterns of inhalant use among incarcerated youth. PLoS One, 10(9). 10.1371/journal.pone.0135303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. In. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Tilson EC (2018). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): an important element of a comprehensive approach to the opioid crisis. North Carolina Medical Journal, 79(3), 166–169. 10.18043/ncm.79.3.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Stouwe T, Asscher JJ, Stams GJJ, Deković M, & van der Laan PH (2014). The effectiveness of multisystemic therapy (MST): a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(6), 468–481. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, Jensen AC, & Maggs JL (2014). Similarities and differences in adolescent siblings’ alcohol-related attitudes, use, and delinquency: evidence for convergent and divergent influence processes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(5), 687–697. 10.1007/s10964-013-9971-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, Jensen AC, & Maggs JL (2013). Similarities in adolescent siblings’ substance use: Testing competing pathways of influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(1), 104–113. 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff KT, Cuevas C, Intravia J, Baglivio MT, & Epps N (2018). The effects of neighborhood context on exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system: Latent classes and contextual effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2279–2300. 10.1007/s10964-018-0887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]