Abstract

Background

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) have been associated with psychiatric disorders in observational studies; however, the causality of associations remains unestablished.

Methods

Specifically, cyclic nucleotide PDEs were collected from genome-wide association studies (GWASs), including PDEs obtained by hydrolyzing both cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (PDE1A, PDE2A, and PDE3A), specific to cGMP (PDE5A, PDE6D, and PDE9A) and cAMP (PDE4D and PDE7A). We performed a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to investigate the relationship between PDEs and nine psychiatric disorders. The inverse-variance-weighted (IVW) method, MR-Egger, and weighted median were used to estimate causal effects. The Cochran’s Q test, MR-Egger intercept test, MR Steiger test, leave-one-out analyses, funnel plot, and MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) were used for sensitivity analyses.

Results

The PDEs specific to cAMP were associated with higher-odds psychiatric disorders. For example, PDE4D and schizophrenia (SCZ) (odds ratios (OR) = 1.0531, PIVW = 0.0414), as well as major depressive disorder (MDD) (OR = 1.0329, PIVW = 0.0011). Similarly, PDE7A was associated with higher odds of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (OR = 1.0861, PIVW = 0.0038). Exploring specific PDE subtypes and increase intracellular cAMP levels can inform the development of targeted interventions. We also observed PDEs (which hydrolyzes both cAMP and cGMP) was associated with psychiatric disorders [OR of PDE1A was 1.0836 for autism spectrum disorder; OR of PDE2A was 0.8968 for Tourette syndrome (TS) and 0.9449 for SCZ; and OR of PDE3A was 0.9796 for MDD; P < 0.05]. Furthermore, psychiatric disorders also had some causal effects on PDEs [obsessive–compulsive disorder on increased PDE6D and decreased PDE2A and PDE4D; anorexia nervosa on decreased PDE9A]. The results of MR were found to be robust using multiple sensitivity analysis.

Conclusions

In this study, potential causal relationships between plasma PDE proteins and psychiatric disorders were established. Exploring other PDE subtypes not included in this study could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role of PDEs in psychiatric disorders. The development of specific medications targeting PDE subtypes may be a promising therapeutic approach for treating psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-023-04368-0.

Keywords: Phosphodiesterase, Psychiatric disorders, cAMP, cGMP, Mendelian randomization study

Introduction

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) hydrolyzes second messenger molecules [cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) or cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)] in cells. The balance between nucleotide cyclase synthesis and hydrolysis inactivation determines the concentration of second messengers [1]. The equilibrium between cAMP and cGMP levels within the nervous system is crucial for learning, memory, and the establishment of neuronal circuits [2, 3]. The levels of both cAMP and cGMP play essential roles in a variety of processes, including axonal development, neurogenesis, axonal neuron polarity, neuronal migration, and synaptic plasticity [2, 4–6]. Also, cAMP and cGMP play significant regulatory roles in cellular activity. Mammalian PDEs are divided into 11 protein subfamilies and are expressed by cells of all tissues [7]. PDE2A exhibits significant expression in specific regions of the human brain, namely the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices. PDE1A mRNA is widely expressed throughout the entire human brain [8].

Psychiatric disorder is one of the major public health challenges worldwide, ranking as the second most significant cause of premature death and disability. People with psychiatric disorder have cognitive, emotional or behavioral changes [9, 10]. An increasing number of studies have recently emphasized the significant impact of PDEs on neuropsychiatric disorders [1, 11]. The genetic variations in PDE genes may be related to neuropsychiatric disorders, according to genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Rs11976985 in the PDE1C gene and rs1513723 in the PDE7A gene were found to exhibit associations with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; P < 1 × 10−4) in a GWAS meta-analysis of more than 16,000 individuals [12]. Informative single-nucleotide polymorphism in PDE1C (rs4720058) and PDE4D (rs7735958) reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) with cognitive performance [13]. PDE2A mRNA expression dysregulation has been observed in the brain regions associated with the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder (BD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and schizophrenia (SCZ) [14]. Inherited missense variants in the PDE1B gene have been identified in probands with SCZ [15]. PDEs have long been recognized as a therapeutic target for a variety of neurological diseases. Recent studies have demonstrated that PDE1 inhibitors can improve both positive and negative symptoms associated with SCZ in animal models [16]. The targeted medications that focus on specific PDE subtypes could serve as a promising therapeutic approach for treating psychiatric disorders. The PDE inhibitors have a positive effect on cognitive function in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [17, 18]. A double-blind study showed that roflumilast (a PDE4 inhibitor) could enhance verbal memory in patients with SCZ [19]. Clinical studies have shown that PDE4 inhibitors can cross blood–brain barriers and provide benefits for neuroprotection and memory improvement in AD [11, 17]. PDE inhibitors hold great promise as pharmacological agents [7, 18].

Increasing evidence shows that PDEs are associated with psychiatric disorders; however, their cause–effect relationship has not been demonstrated. In these circumstances, the Mendelian randomization (MR) study used genetic variants from GWAS as instrumental variables (IVs) for environmental exposure to draw conclusions about the causality of the result [20]. To this end, a bidirectional two-sample MR study was performed to investigate the causal associations between PDEs and psychiatric disorders.

Materials and methods

Study design

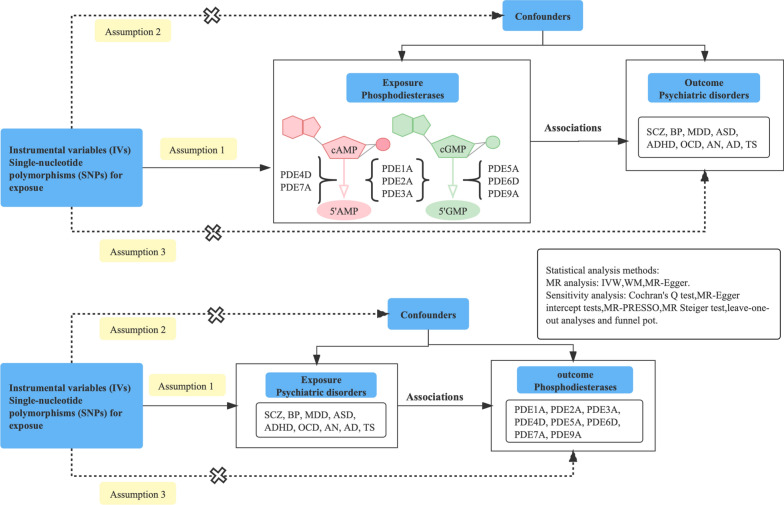

A bidirectional MR design was used to detect the causal effects of eight phosphodiesterases (PDEs) on nine psychiatric disorders. This MR analysis was based on three critical assumptions [21] (Fig. 1). A group of PDEs was obtained by hydrolyzing both cAMP and cGMP (PDE1A, PDE2A, and PDE3A), specific to cGMP (PDE5A, PDE6D, and PDE9A) and cAMP (PDE4D and PDE7A). Psychiatric disorders included AD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anorexia nervosa (AN), ASD, BD, MDD, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), SCZ, and Tourette syndrome (TS).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram. The SNPs from GWAS applied as instrumental variables (IVs) were related to exposures (assumption 1). Dash lines with a cross means that IVs must not be associated with confounders (assumption 2) and IVs affect the risk of outcome directly by exposure and not through other alternative pathways (assumption 3). The dash lines indicate irrelevance, and the solid lines indicate relevance. PDE phosphodiesterase, AD Alzheimer disease, ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, AN anorexia nervosa, ASD autism spectrum disorder, BD bipolar disorder, MDD major depressive disorder, OCD obsessive–compulsive disorder, SCZ schizophrenia, TS Tourette syndrome, IVW inverse-variance weighted, WM weighted-median, MR Mendelian randomization, MR-PRESSO MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier

Data extraction

Data on the genetic associations were obtained from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC: https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/) and the GWAS summary data (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). Only the summarized data of the European population were adopted to reduce the bias of population heterogeneity. Detailed information on the GWAS datasets is provided in Table 1. Informed consent and ethical approval can be found in the original studies.

Table 1.

Detailed information regarding studies and datasets used in the present study

| Exposure or outcome | Preferred names | Source | Ancestry | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphodiesterases | ||||

| PDE1A | Dual specificity calcium/calmodulin-dependent 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 1A | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| PDE2A | cGMP-dependent 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| PDE3A | cGMP-inhibited 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 3A | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| PDE4D | cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4D | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| PDE5A | cGMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase | PMID: 28240269 | European | 997 individuals |

| PDE6D | Retinal rod rhodopsin-sensitive cGMP 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase subunit delta | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| PDE7A | High affinity cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 7A | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| PDE9A | High affinity cGMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 9A | PMID: 29875488 | European | 3301 individuals |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease | PMID: 30617256 | European | 71,880 cases and 383,378 controls |

| ADHD | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | PMID: 29325848 | European | 20,183 cases and 35,191 controls |

| AN | Anorexia nervosa | PMID: 28494655 | European | 3495 cases and 10,982 controls |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder | PMID: 30804558 | European | 18,381 cases and 27,969 controls |

| BD | Bipolar disorder | PMID: 31043756 | European | 20,352 cases and 31,358 controls |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder | PMID: 30718901 | European | 170,756 cases and 329,443 controls |

| OCD | Obsessive–compulsive disorder | PMID: 28761083 | European | 2688 cases and 7,037 controls |

| SCZ | Schizophrenia | PMID: 25056061 | European | 35,476 cases and 46,839 controls |

| TS | Tourette syndrome | PMID: 30818990 | European | 4819 cases and 9488 controls |

We extracted the summary statistics of eight PDEs for plasma proteins from two different proteomic GWASs (accessed on 28 December 2022). The genetic predictors for PDE5A were referred from the KORA study with a sample size of 997 individuals [22]. The remaining summary statistics for PDEs (PDE1A, PDE2A, PDE3A, PDE4D, PDE6D, PDE7A, and PDE9A) were obtained from the INTERVAL study with a sample size of 3301 European participants [23]. Summary statistics for nine psychiatric disorders were obtained from the PGC website (accessed on 2 January 2023). The respective sample sizes were as follows: AD [24] (71,880 cases and 383,378 controls), ADHD [25] (20,183 cases and 35,191 controls), AN [26] (3495 cases and 10,982 controls), ASD [27] (18,381 cases and 27,969 controls), BD [28] (20,352 cases and 31,358 controls), MDD [29] (170,756 cases and 329,443 controls), OCD [30] (2688 cases and 7037 controls), SCZ [31] (35,476 cases and 46,839 controls), and TS [32] (4819 cases and 9488 controls) (Table 1).

Selection of the instrumental variables (IVs)

We selected independent SNPs (P value < 1 × 10−5) from the GWAS summary data of exposure, which allowed for a sufficient number of SNPs. Also, we collected SNPs at linkage disequilibrium (LD) r2 threshold < 0.0001 and kb > 10,000 based on the 1000 Genomes European Sample Project [33]. A minor allele frequency threshold of 0.3 was permitted for palindromic SNPs. We used the PhenoScanner V2 database to consider four potential confounders, including drinking, smoking behavior, socioeconomic status and education [34]. In this study, the IVs were not associated with confounders. SNPs with indirect effects were also removed if they were associated (P value < 0.001) with the outcome. We calculated the power using the F statistics [F = R2 × (N − 2)/(1 − R2)] for each SNP [35]. Further, we evaluated the F statistic values [F = ((R2/(1 − R2)) × ((N − K − 1)/K)] to assess instrument strength for the MR pairs. Briefly, N represents the sample size of the exposure data and the R2 represents the explained variance of genetic instruments. Based on beta (genetic effect size of the exposure) and SE (standard error of effect size), the F statistic values were also obtained using the formula: F = beta2/SE2 [36]. The general F statistic values to measure the power of IV were calculated using 2 methods, with a threshold above 10 implying smaller bias [35].

Mendelian randomization analyses

Three main MR Methods (Inverse variance weighted (IVW) [37], MR-Egger [38], and weighted median (WM) [37]) were used to investigate the causal relationship between the PDEs and psychiatric disorders. For the main IVW method, the random-effects IVW model was chosen to reduce the influence of heterogeneity on the results [37]. For the reliability of the final analysis results, the following screening criteria were used as filters for robust significant causality: (1) At least one of the three main methods (IVW, MR-Egger, and WM) suggested a significant causal relationship. (2) The direction of MR analysis results (beta value) was consistent among all three methods. (3) We apply the maximum likelihood (ML) method to replicate significant causal relationships, considering our reliance on the IVW method. The ML method is similar to IVW in that it must be presumed beforehand that there is no heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy among the IVs. If the IVs meet the assumptions, the results will be unbiased and the standard error will be lesser than with IVW [39]. The Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was conducted to correct P values. A P value less than 3.47 × 10−4 (0.05/72/2; 2 denotes both forward and reverse MR tests) was considered as strong evidence of a causal association. A P value less than 0.05 was considered as suggestive evidence for a potential causal association.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify any horizontal pleiotropy that would contradict the main MR hypotheses. Thus, we performed MR-Egger intercept tests, Cochran’s Q test, leave-one-out analyses, funnel plot, MR-PRESSO, and MR Steiger test to evaluate the robustness of the results.

The leave-one-out analysis was performed to detect the causal estimates driven by a single SNP. Specifically, the Cochran Q test was used for the IVW model to evaluate the heterogeneity [40]. The MR-Egger regression was used to examine the mean pleiotropic effect of all IVs. The global MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) (https://github.com/rondolab/MR-PRESSO/) test was introduced to explore the possible outlier SNPs and detect the presence of horizontal pleiotropy [41]. Additionally, we performed the MR Steiger directionality test to estimate the potential causal association hypothesis between PDEs and psychiatric disorders. MR analyses were conducted using the TwoSampleMR package (version 0.5.6) [42].

Results

Genetic instruments selected in MR

The study design is shown in Fig. 1. After LD pruning, the outlier IVs based on the funnel plot (Additional file 2: Figs. S1–S18) were also removed for subsequent MR analysis. The details of IVs used in the MR analysis of the association between PDE proteins and psychiatric disorders are provided in Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2. For the instrument strength for the forward and reverse MR pairs; the F statistic values were all ≥ 10 (Additional file 1: Tables S3 and S4).

Causal effect of genetically predicted PDEs on psychiatric disorders

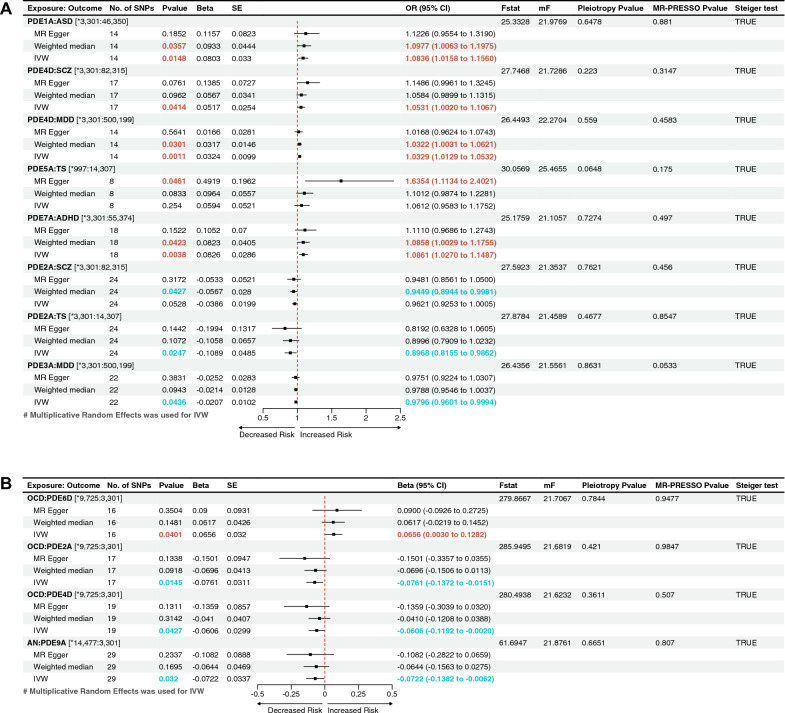

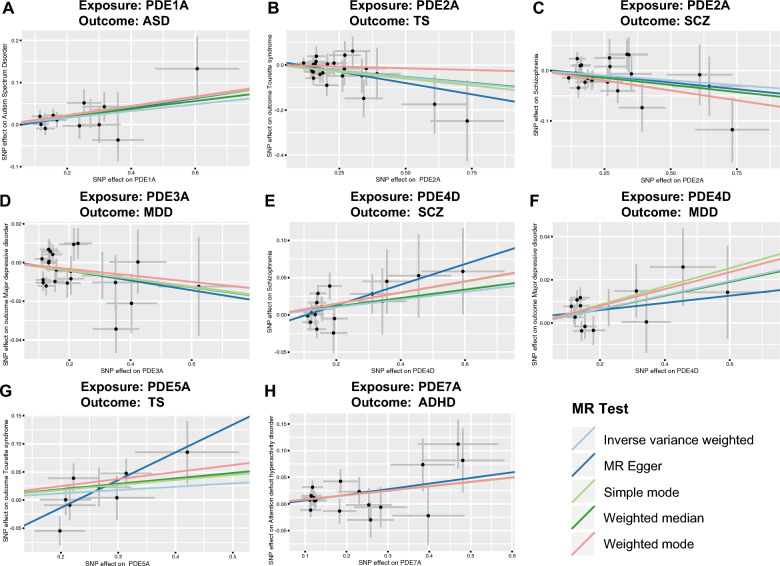

The results showed that part of the PDEs was nominally associated with the increased risk of psychiatric disorders (Fig. 2). They were as follows: PDE1A, ASD (odds ratio (OR) = 1.0836, 95% CI 1.0158–1.1560, PIVW = 0.0148); PDE4D, SCZ (OR = 1.0531, 95% CI 1.0020–1.1067, PIVW = 0.0414); PDE4D, MDD (OR = 1.0329, 95% CI 1.0129–1.0532, PIVW = 0.0011); PDE7A, ADHD (OR = 1.0861, 95% CI 1.0270–1.1487, PIVW = 0.0038); PDE5A, TS (OR = 1.6354, 95% CI 1.1134–2.4021, PMR-Egger = 0.0461). PDE2A was associated with lower-odds SCZ (OR = 0.9449, 95% CI 0.8944–0.9981, PWM = 0.0427) and lower-odds TS (OR = 0.8968, 95% CI 0.8155–0.9862; PIVW = 0.0247). PDE3A was associated with lower-odds MDD (OR = 0.9796, 95% CI 0.9601–0.9994, PIVW = 0.0436). These results of IVW, WM, and MR-Egger tests indicated consistent direction (Fig. 2A). The Bonferroni-corrected threshold (P < 3.47 × 10−4) served as the statistically significant evidence of a causal association. However, the results provided suggestive evidence of the impact of PDEs on psychiatric disorders. The scatter plots of the effect of PDEs on psychiatric disorders are shown in Fig. 3. The detailed results can be viewed in Additional file 1: Table S5.

Fig. 2.

The forest plot shows the significant causalities. Associations between genetically predicted phosphodiesterases (PDEs) and the risk of psychiatric disorders (A). Associations between genetically predicted psychiatric disorders and PDEs (B). The causal relationships between PDEs and the risk of psychiatric disorders were presented using OR and 95% CIs. Additionally, beta and 95% CIs were used to present the causal relationships between psychiatric disorders and PDEs. Both the pleiotropy p value and the MR-PRESSO p value are greater than 0.05, which means that there is no directional pleiotropy and horizontal pleiotropy. No number, SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, beta, genetic effect size from the exposure GWAS data, SE standard error of effect size, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval; F-statistic, [F = ((R2/(1 − R2)) × ((N − K − 1)/K)]; mF, F = beta2/SE2; Pleiotropy p value, Egger intercept p value; MR, Mendelian randomization; MR-PRESSO p value, MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier “Global Test” p value. *The sample size of the respective genome-wide association study (GWAS) datasets

Fig. 3.

Scatterplot of the effect of the phosphodiesterases (PDEs) on psychiatric disorders. The effect of the PDEs on psychiatric disorders is calculated through instrumental variables (IVs), which provide an association between the PDEs and psychiatric disorders through five Mendelian randomization (MR) methods (A–H). The slope value equals the b-value calculated using the five methods and represents the causal effect. Positive slope indicates that exposure is a risk factor, whereas a negative slope is the opposite. PDE phosphodiesterase, ASD autism spectrum disorder, TS Tourette syndrome, SCZ schizophrenia, MDD major depressive disorder, ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Causal effect of genetically predicted psychiatric disorders on PDEs

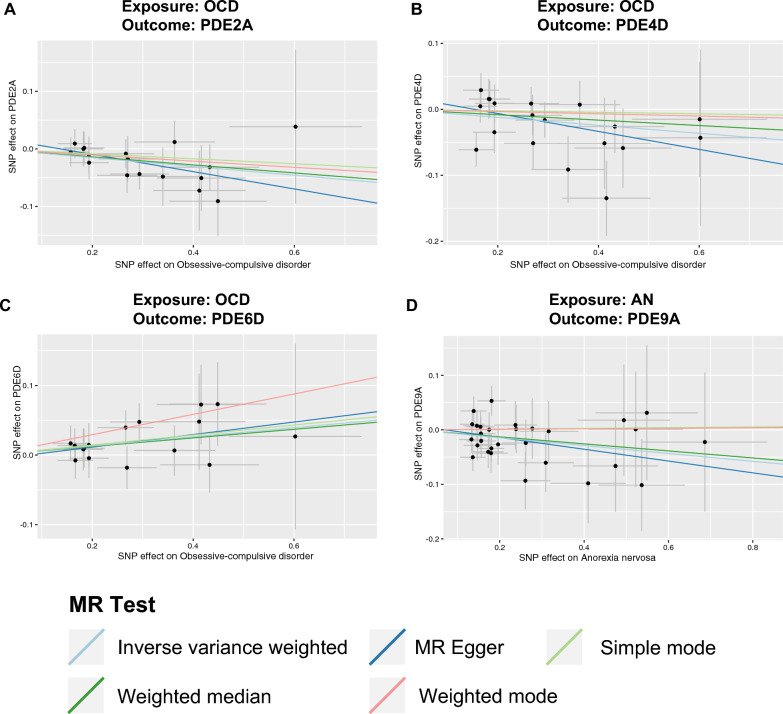

The reverse MR analysis was conducted to investigate the putative causal effects of psychiatric disorders on PDEs (Additional file 1: Table S6). A P value less than 0.05 indicated suggestive evidence (Fig. 2B). The results showed a nominal causal effect of OCD on increased PDE6D (beta = 0.0656, 95% CI 0.0030–0.1282, PIVW = 0.0401), decreased PDE2A (beta = − 0.0761, 95% CI − 0.1372 to − 0.0151, PIVW = 0.0145) and decreased PDE4D (beta = − 0.0606, 95% CI − 0.1192 to − 0.0020, PIVW = 0.0427). AN was nominally associated with decreased PDE9A (beta = − 0.0722, 95% CI − 0.1382 to − 0.0062, PIVW = 0.032). The scatter plots of the effect of PDEs on psychiatric disorders are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot of the effect of the psychiatric disorders on PDEs. An association between the psychiatric disorders on PDEs through five Mendelian randomization (MR) methods (A–D). The slope value equals the b-value calculated using the five methods and represents the causal effect. Positive slope indicates that exposure is a risk factor, whereas a negative slope is the opposite. OCD obsessive–compulsive disorder, PDE phosphodiesterase, AN anorexia nervosa

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses to verify our putative causalities obtained with bidirectional MR (Table 2). First, as shown by the funnel plot, the effect size variation around the point estimate was symmetrical after excluding outliner SNPs (Additional file 2: Figs. S1–S18). The MR-PRESSO test provided no evidence of possible outliers. Second, all P values were > 0.05 in the MR-PRESSO global tests, Cochran’s Q tests, and the MR-Egger intercept tests, manifesting no evidence of heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy. Third, the “leave-one-out” method confirmed that single SNPs did not affect the causal association (Additional file 2: Figs. S19–S30). Fourth, the directions of the estimates from the WM and MR-Egger tests were the same as those from the IVW method.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis of the causal association between PDEs proteins and psychiatric disorders

| Exposure: outcome | MR-Eegger_Intercept | Egger_intercept_pvala | IVW_Cochrane_Q | IVW_Cochrane_Q_pvalb | MR-PRESSO Pvaluec | Steiger_testd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDE1A: ASD | − 0.0069 | 0.6478 | 7.6507 | 0.8656 | 0.8810 | TRUE |

| PDE2A: SCZ | 0.0031 | 0.7621 | 23.5793 | 0.4274 | 0.4560 | TRUE |

| PDE2A: TS | 0.0190 | 0.4677 | 15.6579 | 0.8695 | 0.8547 | TRUE |

| PDE3A: MDD | 0.0008 | 0.8631 | 33.4772 | 0.0412 | 0.0533 | TRUE |

| PDE4D: MDD | 0.0027 | 0.5590 | 13.0823 | 0.4415 | 0.4583 | TRUE |

| PDE4D: SCZ | − 0.0148 | 0.2230 | 18.0200 | 0.3227 | 0.3147 | TRUE |

| PDE5A: TS | − 0.1120 | 0.0648 | 10.8504 | 0.1453 | 0.1750 | TRUE |

| PDE7A: ADHD | − 0.0039 | 0.7274 | 16.6441 | 0.4787 | 0.4970 | TRUE |

| OCD: PDE2A | 0.0205 | 0.4210 | 6.1782 | 0.9861 | 0.9847 | TRUE |

| OCD: PDE4D | 0.0208 | 0.3611 | 18.0066 | 0.4552 | 0.5070 | TRUE |

| OCD: PDE6D | − 0.0065 | 0.7844 | 6.8627 | 0.9613 | 0.9477 | TRUE |

| AN: PDE9A | 0.0077 | 0.6651 | 21.5561 | 0.8014 | 0.8070 | TRUE |

| AD: PDE7A | − 0.0022 | 0.6965 | 67.5274 | 0.4247 | 0.4727 | FALSE |

Q Cochran’s Q statistics, IVW inverse-variance weighted, MR Mendelian randomization, MR-PRESSO MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier, PDE phosphodiesterase, ASD autism spectrum disorder, SCZ schizophrenia, TS Tourette syndrome, MDD major depressive disorder, ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, OCD obsessive–compulsive disorder, AN anorexia nervosa, AD Alzheimer’s disease

aThe MR–Egger intercept quantifies the effect of directional pleiotropy (P < 0.05, which means possible directional pleiotropy)

bThe Cochrane—Q test quantifies the effect of heterogeneity (P < 0.05, which means possible heterogeneity, thus prioritizing “random—IVW” methods)

cMR-PRESSO test quantifies the effect of horizontal pleiotropy (P < 0.05, which means possible horizontal pleiotropy)

dMR-Steiger directionality test to assess the potential causal relationship (FALSE, which means an inverse causal link)

Additionally, the MR Steiger test was used to detect the reliability of the causal direction. The Steiger test result between AD and PDE7A was FALSE, suggesting an inverse causal link (Table 2). However, the results of the MR Steiger test supported our conclusions regarding 12 potential causal relationships between PDEs and psychiatric disorders (Fig. 2).

Using the ML method, we replicated the vast majority of significant causal relationships (PML < 0.05), except for the relationship from PDE5A to TS (PML = 0.241). This result supports the robustness of our analysis of the causal relationship between PDEs and psychiatric disorders, avoiding the occurrence of accidental errors. The Additional file 2: Fig. S31 shows the results of the re-MR analysis using the ML method.

Discussion

In the present study, we performed bidirectional MR analyses to systematically evaluate the causal associations between eight PDEs and nine psychiatric disorders. The forward MR analysis showed that genetically predicted PDEs specific to cAMP were associated with higher-odds psychiatric disorders. For example, PDE4D was associated with higher odds of SCZ and MDD, while PDE7A was associated with higher odds of ADHD. Additionally, suggestive evidence for PDE1A (which hydrolyzes both cAMP and cGMP) on ASD was obtained. We observed a negative association of PDE2A with SCZ, PDE2A with TS, and PDE3A with MDD. The reverse MR analysis showed that OCD was associated with increased PDE6D, and decreased PDE2A and PDE4D. AN was associated with decreased PDE9A.

The observational studies reported that PDEs were associated with psychiatric disorders. This was the first MR study to estimate the causal association between PDEs and psychiatric disorders. MR examined causality with the large-scale GWAS data using genetic polymorphisms as a proxy for exposure [43]. The suggestive causal associations were found between PDEs and psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, the consistency across sensitivity analyses further reinforces the credibility of the effect estimates. The intracellular concentrations of cyclic nucleotides are regulated by PDE hydrolases that change cAMP and cGMP into 5′AMP and 5′GMP [1]. These associations suggest that the dysregulation between PDEs and cAMP/cGMP signaling as a potential cause of psychiatric disorders. The improved effects of PDE activity regulation on cognitive symptoms and depressive behavior have also gained attention, supporting the notion that PDEs play a role in the pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of psychosis [18, 44]. The pharmacological effects of PDE inhibitors have also been investigated [44], and the clinical trials for PDE target-specific drugs are still ongoing [18].

In this study, PDE4D protein was positively correlated with both the risk of SCZ and the risk of MDD. Our findings provided evidence that PDE4 was a potential therapeutic drug target. PDE4 is an isoenzyme with multiple isoforms, which is widely expressed in a variety of tissues and primarily hydrolyzes cAMP. Previously studied antipsychotics can increase intracellular cAMP levels by antagonizing neurotransmitter receptors [45]. Inhibition of PDE4 can increase intracellular cAMP levels while functionally salvaging synaptic defects [46]. The activity of PDE regulates cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB) and cAMP-activating protein kinase A (PKA) [47]. Numerous studies on animals have demonstrated the potent antidepressant effects of PDE4 inhibitors [44, 48]. Rolipram, a PDE4 inhibitor, increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression through cAMP/CREB and exerts antidepressant effects [49, 50]. The genetic factors disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) and PDE4 collaborate to regulate cAMP signaling in schizophrenia [46, 51]. Roflumilast (a PDE4 inhibitor) can enhance verbal and working memory in patients with SCZ [19]. The second messengers, cAMP and cGMP, influence a wide range of physiological processes, including neurotransmitter signaling, inflammation, molecular signal transduction, and the transcription of many genes [2, 52, 53]. Significantly, a majority of PDEs, which belong to an enzyme family that controls cAMP and cGMP levels, are found in the nervous system and all neurons [54].

PDE7 inhibitors promote neural differentiation and neuroprotection by activating the cAMP/PKA signaling [55]. In this study, PDE7A was associated with an increased risk of ADHD. Inhibiting PDE7A improves cAMP/CREB signaling, encourages the differentiation of neural stem cells, and improves memory and learning, according to rodent model studies [56, 57]. PDE7A and PDE7B play a role in regulating dopaminergic signaling and are primarily expressed in the striatum. Studies have also revealed the therapeutic potential of S14, a small-molecule inhibitor of PDE7, in treating neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Parkinson’s disease [57]. PDE7 is a new potential immunopharmacological anti-inflammatory target for treating chronic inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases [58]. Exploring specific PDE isoforms and increase intracellular cAMP levels can deepen our understanding and inform the development of targeted interventions.

Psychiatric medications have shown inconsistent responses to the cAMP cascade. Previous study demonstrated that haloperidol increased cAMP levels, chronic usage of clozapine has been found to decrease cAMP levels [59]. The forward MR analysis identified PDE1A as a risk factors for ASD, while suggesting potential protective effects of PDE2A in SCZ and TS. The genetic variations in PDE1C and PDE7A were found to be associated with ASD in the GWAS study, which examined 7387 cases of ASD and 8567 controls [12]. Decreased PDE2A mRNA levels were found in BD and SCZ, with changes most pronounced in the frontal cortical regions of SCZ patients and the hippocampus and striatum of BD patients [14]. A link between SCZ and MDD and the levels of the PDE2A protein was not established in this study using reverse MR analysis. Homozygous mutations in PDE2A have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental and intellectual disability [60, 61]. This study found that alterations in PDE protein levels were associated with OCD and AN, but they were not identified as risk or protective factors. In association studies of Chinese populations, rs1838733 in the PDE4D gene was found to be associated with OCD [62]. However, more research is needed to fully understand the role of PDEs in psychiatric disorders and to determine whether targeting this enzyme could be a viable treatment option for individuals with the disorder. PDE tracers can allow specific changes in different brain regions to be observed by PET imaging in vivo, while nanomedicines can target and release drugs [63–65]. There is potential to evaluate potential PDE drugs for different psychiatric disorders in the future and combine them with new technologies. Much directed laboratory and clinical studies in humans are needed to fully understand the impact of PDE subtypes in psychiatric disorders.

The present study had several advantages. First, nine psychiatric disorders and eight PDEs were included, making it the first comprehensive MR study on the association between the PDE system and psychiatric disorders. Second, multiple sensitivity analyses provided evidence that the assumed causal effect in our MR results was reliable. However, this study also had some limitations. First, the P-value threshold was set at 1 × 10−5 to ensure that sufficient SNPs were included to maintain the study power. The study had no weak IVs according to the F statistics. The GWAS studies included in this research are based on European populations. Second, other PDEs that were not included in the analysis might also have importance in psychiatric disorders. Further, the potential causal associations reported in this study should be interpreted with caution, given that the P values were almost at nominal levels. Third, MR analysis uses exposure risk SNPs to examine the impact of lifetime exposure on outcomes, and the effect sizes of MR analyses may be different from those of randomized controlled trials of short-term interventions. To address the limitations mentioned, larger and more diverse datasets, conduct replication studies are required to fully comprehend the genetic implications on exposures. And future research could include populations with different characteristics (such as race and age) in MR studies may increase the representation of different populations. Exploring other PDE subtypes not included in this study could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role of PDEs in psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach involving functional studies, genetic investigations and clinical trials can investigate the mechanisms through which PDEs influence psychiatric disorders could offer insights into potential therapeutic targets and pathways.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this bidirectional MR study provided additional insights into the relationships between PDEs and psychiatric disorders. Our findings implied that PDEs and cAMP/cGMP defense might be useful in etiological research and personalized medicine in psychiatric disorders. The PDEs are potential candidates as novel drug targets for psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Instrumental variables used in MR analysis of the association between PDEs protein and psychosis. Table S2. Instrumental variables used in MR analysis of the association between psychosis and PDEs protein. Table S3. Sensitivity analysis of the causal association between PDEs protein on psychosis. Table S4. Sensitivity analysis of the causal association between psychosis on PDEs protein. Table S5. Mendelian Randomization estimation for PDEs on the risk of psychosis. Table S6. Mendelian Randomization estimation for psychosis on the risk of PDEs.

Additional file 2: Figures S1–S30. The Funnel plot and Leave-one-out analysis between PDEs protein and psychosis. Figure S31. The forest plot shows the significant causalities by maximum likelihood (ML) methods.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge all of the participants and investigators for contributing and sharing summary-level data on GWAS.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- AN

Anorexia nervosa

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- BD

Bipolar disorder

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- cGMP

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- IVW

Inverse variance weighted method

- MDD

Major depressive disorder

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- OCD

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

- OR

Odds ratios

- PDE

Phosphodiesterase

- SCZ

Schizophrenia

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TS

Tourette syndrome

Author contributions

MJ, DZ, JL, and LW conceived and designed the study. MJ, WY, YZ, LZ and TL contributed to data curation. MJ and WY contributed to methodology and visualization. MJ wrote the original manuscript. DZ, JL, and LW revised the article and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2019B030335001), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 81971283, 82171537, 82071541, 81671363, and 81730037).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Additional files. The code for this article can be found online at: https://github.com/YWH199310/MR_-process_code, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Consent for publication

All authors read the final version and approved it.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Miaomiao Jiang and Weiheng Yan contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jun Li, Email: junli1985@bjmu.edu.cn.

Lifang Wang, Email: lifangwang@bjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Azevedo MF, Faucz FR, Bimpaki E, Horvath A, Levy I, de Alexandre RB, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of the phosphodiesterases (PDEs) Endocr Rev. 2014;35:195–233. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Averaimo S, Nicol X. Intermingled cAMP, cGMP and calcium spatiotemporal dynamics in developing neuronal circuits. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:376. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Son H, Lu YF, Zhuo M, Arancio O, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. The specific role of cGMP in hippocampal LTP. Learn Mem. 1998;5:231–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelly M, Lim BK, Cancedda L, Heilshorn SC, Gao H, Poo MM. Local and long-range reciprocal regulation of cAMP and cGMP in axon/dendrite formation. Science. 2010;327:547–552. doi: 10.1126/science.1179735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechay KR, Abduljawad N, Latifi S, Suzuki K, Iwashita H, Carmichael ST. PDE2A inhibition enhances axonal sprouting, functional connectivity, and recovery after stroke. J Neurosci. 2022;42:8225–8236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-22.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urrutia PJ, Gonzalez-Billault C. A role for second messengers in axodendritic neuronal polarity. J Neurosci. 2023;43:2037–2052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1065-19.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakics V, Karran EH, Boess FG. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:240–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat A, Ray B, Mahalakshmi AM, Tuladhar S, Nandakumar DN, Srinivasan M, et al. Phosphodiesterase-4 enzyme as a therapeutic target in neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2020;160:105078. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Autism Spectrum Disorders Working Group of The Psychiatric Genomics C Meta-analysis of GWAS of over 16,000 individuals with autism spectrum disorder highlights a novel locus at 10q24.32 and a significant overlap with schizophrenia. Mol Autism. 2017;8:21. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurney ME. Genetic association of phosphodiesterases with human cognitive performance. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:22. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer R, Burbano SD, Patel NS, Sarmiento A, Smith AJ, Kelly MP. Phosphodiesterases PDE2A and PDE10A both change mRNA expression in the human brain with age, but only PDE2A changes in a region-specific manner with psychiatric disease. Cell Signal. 2020;70:109592. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John J, Bhattacharyya U, Yadav N, Kukshal P, Bhatia T, Nimgaonkar VL, et al. Multiple rare inherited variants in a four generation schizophrenia family offer leads for complex mode of disease inheritance. Schizophr Res. 2020;216:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enomoto T, Tatara A, Goda M, Nishizato Y, Nishigori K, Kitamura A, et al. A novel phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitor DSR-141562 exhibits efficacies in animal models for positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms associated with schizophrenia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371:692–702. doi: 10.1124/jpet.119.260869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li YF, Cheng YF, Huang Y, Conti M, Wilson SP, O'Donnell JM, et al. Phosphodiesterase-4D knock-out and RNA interference-mediated knock-down enhance memory and increase hippocampal neurogenesis via increased cAMP signaling. J Neurosci. 2011;31:172–183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5236-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prickaerts J, Heckman PRA, Blokland A. Investigational phosphodiesterase inhibitors in phase I and phase II clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:1033–1048. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1364360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilleen J, Farah Y, Davison C, Kerins S, Valdearenas L, Uz T, et al. An experimental medicine study of the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, roflumilast, on working memory-related brain activity and episodic memory in schizophrenia patients. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238:1279–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-5134-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey SG. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27:1133–1163. doi: 10.1002/sim.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawlor DA. Commentary: Two-sample Mendelian randomization: opportunities and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:908–915. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suhre K, Arnold M, Bhagwat AM, Cotton RJ, Engelke R, Raffler J, et al. Connecting genetic risk to disease end points through the human blood plasma proteome. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature. 2018;558:73–79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin J, Walters RK, Demontis D, Mattheisen M, Lee SH, Robinson E, et al. A genetic investigation of sex bias in the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duncan L, Yilmaz Z, Gaspar H, Walters R, Goldstein J, Anttila V, et al. Significant locus and metabolic genetic correlations revealed in genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:850–858. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grove J, Ripke S, Als TD, Mattheisen M, Walters RK, Won H, et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:431–444. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stahl EA, Breen G, Forstner AJ, McQuillin A, Ripke S, Trubetskoy V, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:793–803. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:343–352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics C. Studies OCDCGA Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive–compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1181–1188. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu D, Sul JH, Tsetsos F, Nawaz MS, Huang AY, Zelaya I, et al. Interrogating the genetic determinants of Tourette’s syndrome and other tic disorders through genome-wide association studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:217–227. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genomes Project C. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamat MA, Blackshaw JA, Young R, Surendran P, Burgess S, Danesh J, et al. PhenoScanner V2: an expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4851–4853. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess S, Thompson SG, Collaboration CCG. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–764. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie J, Huang H, Liu Z, Li Y, Yu C, Xu L, et al. The associations between modifiable risk factors and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2023;77:949–964. doi: 10.1002/hep.32728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgess S, Dudbridge F, Thompson SG. Combining information on multiple instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization: comparison of allele score and summarized data methods. Stat Med. 2016;35:1880–1906. doi: 10.1002/sim.6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierce BL, Burgess S. Efficient design for Mendelian randomization studies: subsample and 2-sample instrumental variable estimators. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1177–1184. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greco MF, Minelli C, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Detecting pleiotropy in Mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome. Stat Med. 2015;34:2926–2940. doi: 10.1002/sim.6522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu X, Dou M, Cao B, Jiang Z, Chen Y. Peripheral level of CD33 and Alzheimer’s disease: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:427. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02205-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:R89–98. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang HT, Huang Y, Jin SL, Frith SA, Suvarna N, Conti M, et al. Antidepressant-like profile and reduced sensitivity to rolipram in mice deficient in the PDE4D phosphodiesterase enzyme. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:587–595. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanes SJ, Tokarczyk J, Siegel SJ, Bilker W, Abel T, Kelly MP. Rolipram: a specific phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor with potential antipsychotic activity. Neuroscience. 2007;144:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim NS, Wen Z, Liu J, Zhou Y, Guo Z, Xu C, et al. Pharmacological rescue in patient iPSC and mouse models with a rare DISC1 mutation. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1398. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21713-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang ZZ, Yang WX, Zhang Y, Zhao N, Zhang YZ, Liu YQ, et al. Phosphodiesterase-4D knock-down in the prefrontal cortex alleviates chronic unpredictable stress-induced depressive-like behaviors and memory deficits in mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11332. doi: 10.1038/srep11332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Itoh T, Abe K, Tokumura M, Horiuchi M, Inoue O, Ibii N. Different regulation of adenylyl cyclase and rolipram-sensitive phosphodiesterase activity on the frontal cortex and hippocampus in learned helplessness rats. Brain Res. 2003;991:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Houslay MD, Schafer P, Zhang KY. Keynote review: phosphodiesterase-4 as a therapeutic target. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1503–1519. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Millar JK, Pickard BS, Mackie S, James R, Christie S, Buchanan SR, et al. DISC1 and PDE4B are interacting genetic factors in schizophrenia that regulate cAMP signaling. Science. 2005;310:1187–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1112915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biel M, Michalakis S. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Berlin: Springer; 2009. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels; pp. 111–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houslay MD, Milligan G. Tailoring cAMP-signalling responses through isoform multiplicity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menniti FS, Faraci WS, Schmidt CJ. Phosphodiesterases in the CNS: targets for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:660–670. doi: 10.1038/nrd2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sasaki T, Kotera J, Omori K. Transcriptional activation of phosphodiesterase 7B1 by dopamine D1 receptor stimulation through the cyclic AMP/cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase/cyclic AMP-response element binding protein pathway in primary striatal neurons. J Neurochem. 2004;89:474–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Y, Chen Y, Kang Z, Li S. Inhibiting PDE7A enhances the protective effects of neural stem cells on neurodegeneration and memory deficits in sevoflurane-exposed mice. eNeuro. 2021 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0071-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morales-Garcia JA, Redondo M, Alonso-Gil S, Gil C, Perez C, Martinez A, et al. Phosphodiesterase 7 inhibition preserves dopaminergic neurons in cellular and rodent models of Parkinson disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Safavi M, Baeeri M, Abdollahi M. New methods for the discovery and synthesis of PDE7 inhibitors as new drugs for neurological and inflammatory disorders. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2013;8:733–751. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2013.787986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seo MS, Scarr E, Lai CY, Dean B. Potential molecular and cellular mechanism of psychotropic drugs. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2014;12:94–110. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2014.12.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haidar Z, Jalkh N, Corbani S, Abou-Ghoch J, Fawaz A, Mehawej C, et al. A homozygous splicing mutation in PDE2A in a family with atypical rett syndrome. Mov Disord. 2020;35:896–899. doi: 10.1002/mds.28023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salpietro V, Perez-Duenas B, Nakashima K, San Antonio-Arce V, Manole A, Efthymiou S, et al. A homozygous loss-of-function mutation in PDE2A associated to early-onset hereditary chorea. Mov Disord. 2018;33:482–488. doi: 10.1002/mds.27286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang X, Zhang J, Liu J, Zhang X. Association study of the PDE4D gene and obsessive-compulsive disorder in a Chinese Han population. Psychiatr Genet. 2019;29:226–231. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naganawa M, Waterhouse RN, Nabulsi N, Lin SF, Labaree D, Ropchan J, et al. First-in-human assessment of the novel PDE2A PET radiotracer 18F-PF-05270430. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1388–1395. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.166850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khalilov R. A comprehensive review of advanced nano-biomaterials in regenerative medicine and drug delivery. Adv Biol Earth Sci. 2023;8(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hasanzadeh A, et al. Development of doxorubicin-adsorbed magnetic nanoparticles modified with biocompatible copolymers for targeted drug delivery in lung cancer. Adv Biol Earth Sci. 2017;2(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Instrumental variables used in MR analysis of the association between PDEs protein and psychosis. Table S2. Instrumental variables used in MR analysis of the association between psychosis and PDEs protein. Table S3. Sensitivity analysis of the causal association between PDEs protein on psychosis. Table S4. Sensitivity analysis of the causal association between psychosis on PDEs protein. Table S5. Mendelian Randomization estimation for PDEs on the risk of psychosis. Table S6. Mendelian Randomization estimation for psychosis on the risk of PDEs.

Additional file 2: Figures S1–S30. The Funnel plot and Leave-one-out analysis between PDEs protein and psychosis. Figure S31. The forest plot shows the significant causalities by maximum likelihood (ML) methods.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Additional files. The code for this article can be found online at: https://github.com/YWH199310/MR_-process_code, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.