Abstract

Background

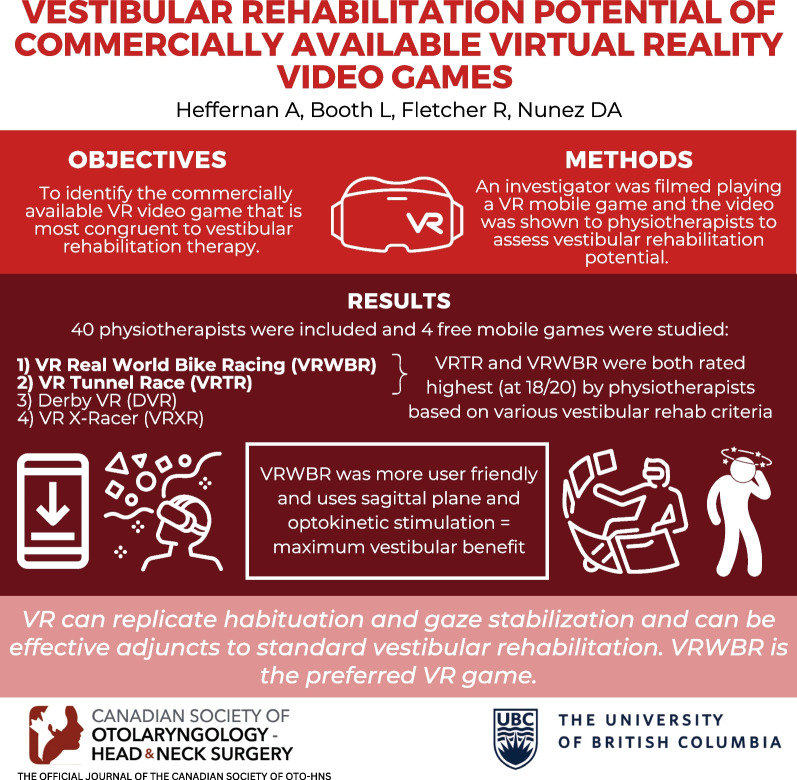

Peripheral vestibular disorders affect 2.8–6.5% of people. Standard treatment is vestibular rehabilitation therapy, and virtual reality (VR) could improve outcomes. The objective of this study was to identify the commercially available VR video game that is most congruent to vestibular rehabilitation therapy.

Methods

A term search “virtual reality racing” was performed on the App Store in March 2022. Results were screened for free point-of-view racing games compatible with Android and iOS devices. An investigator was filmed playing each game and videos were distributed to 237 physiotherapists. Physiotherapists completed a survey of 5-point Likert scale questions that assessed the video games vestibular rehabilitation potential. Survey responses were analyzed using Friedman Two-Way ANOVA (alpha = 0.05) and paired samples sign test with Bonferroni correction.

Results

The search yielded 58 games, 4 were included. Forty physiotherapists participated. VR Tunnel Race (VRTR) and VR Real World Bike Racing (VRWBR) had the greatest vestibular rehabilitation potential (median global scores = 18.00). VRTR replicated habituation exercises significantly (p < 0.001) better than Derby VR, and VRWBR replicated physiotherapist-prescribed exercises significantly (p < 0.001) better than VR X-Racer. There were no discernable significant differences between VRWBR and VRTR.

Conclusions

VRTR and VRWBR are the most congruent VR games to standard vestibular rehabilitation. VRWBR is preferable to VRTR with respect to ease of use and the ability to alter the amount of optokinetic stimulation. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of these videos games and to determine if they could be used as solitary treatments.

Trial registration: Not applicable.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Vestibular rehabilitation, Virtual reality, Head-mounted device, Video game, Vestibular hypofunction, Peripheral vestibular disorder, Physiotherapy

Background

Peripheral vestibular disorders are highly morbid conditions that affect 2.8–6.5% of the population (women more frequently than men) and become more prevalent with age [1, 2]. The inner ear, specifically the vestibular apparatus and or its innervations are the site of pathology in these disorders. Dysfunction of different parts of the vestibular apparatus presents as several different peripheral vestibular disorders, including benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Menière’s disease and vestibular neuritis. These can lead to symptoms of dizziness, imbalance, nausea, oscillopsia and occasional falling which can greatly reduce a patient’s quality of life [3]. In addition, the majority of patients with chronic symptoms develop depression and anxiety associated with their peripheral vestibular disorder [4, 5].

Current treatments for peripheral vestibular disorders are pharmacological, surgical, or physical including repositioning maneuvers and standard vestibular rehabilitation (SVR). The latter involves a range of exercises that include habituation, substitution, and adaptation exercises, where there is moderate evidence in support of virtual reality (VR) as a mode of delivering these exercises [6]. The interventions range from generic Cooksey Cawthorne to patient customized exercises [7]. These exert their effects by promoting adaptation of residual vestibular function, substitution of alternative strategies for lost vestibular function and habituation to unpleasant sensations [8, 9]. These mechanisms help to achieve the goals of SVR; namely to enhance postural stability, improve gaze, reduce vertigo, and improve the scope and scale of activities of daily living [10]. Despite these intentions, SVR is considered physical rehabilitation (PR), thus it is subject to the same factors that affect PR adherence including preconceptions of PR, perceived exertion during sessions, financial barriers, and inconvenience for the patient [11, 12].

VR could serve as an adjunctive therapy to SVR and may address adherence issues while improving outcomes. VR is defined as technology that immerses the wearer into an interactive environment that mimics reality [13]. This technology has been used in research as an adjunct to SVR sessions in both hospital and home settings. Studies of in hospital VR in patients with vestibular disease have involved the completion of SVR exercises while immersed in a VR environment with or without additional co-interventions [14–16]. In hospital VR has been shown to successfully improve stability, reduce dizziness, enhance quality of life, and reduce visual vertigo symptoms in these patients [14–16]. Recent meta-analyses support hospital VR as an effective and well tolerated intervention for vestibular disorders [17, 18]. Home based VR (HBVR) studies have required patients to play a 3D game utilizing a head mounted display (HMD) device in addition to completing in-clinic SVR and at home exercises [19, 20]. The addition of the HBVR gaming procedure to SVR significantly improved vestibular ocular reflex (VOR) gain, stability, balance confidence and patient quality of life compared to SVR and at home exercises [18–20].

HBVR video game exercises are thus a promising adjunct to SVR. However, there is a paucity of literature on which VR games are best suited for SVR, with Micarelli et al. utilizing a point-of-view VR racing game based on their judgment that it replicated SVR exercises [19, 20]. However, their video game selection was not conducted systematically and there is no consensus on what types of commercially available VR video games best replicate SVR exercises. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine which commercially available VR video game is most congruent with SVR exercises for peripheral vestibular disorders.

Methods

Video game selection

Virtual reality is defined as the immersion of the user in a digital environment that mimics the real world [13]. In contrast, augmented reality alters reality by projecting computer-generated sound, text and graphics onto the user’s natural visual and auditory fields [21]. Previous studies demonstrated that at home virtual reality racing games were effective as adjunctive vestibular rehabilitation [19, 20], hence racing games were the type of virtual reality games adopted for this study. Virtual reality video game selection was conducted systematically by searching “virtual reality racing” on the iOS App Store in March 2022. Video games were eligible if they were considered virtual reality point-of-view racing games that were free, had smooth functionality and were compatible with both iOS and Android. Video games were excluded if they required a joystick or were augmented reality video games. These video games were played on an iOS device placed in VR Shinecon G10 Virtual Reality Glasses. Copyright © (2022) Shinecon (Dongguan, China).

Survey design

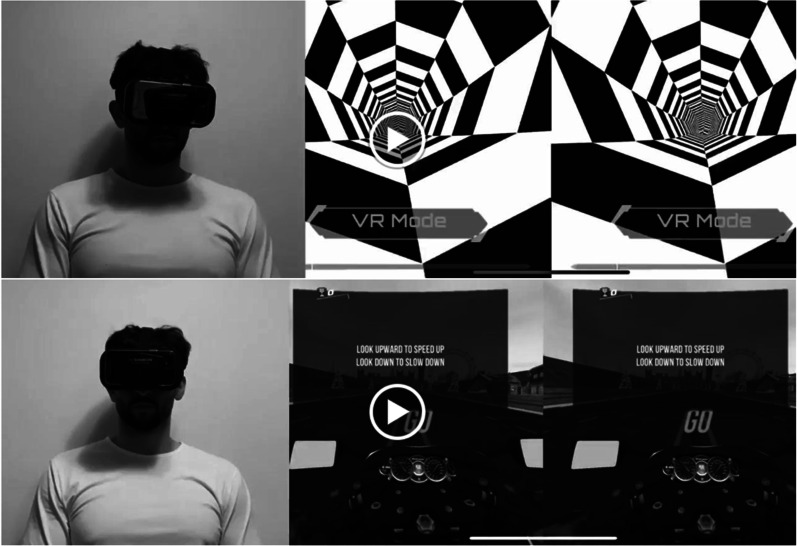

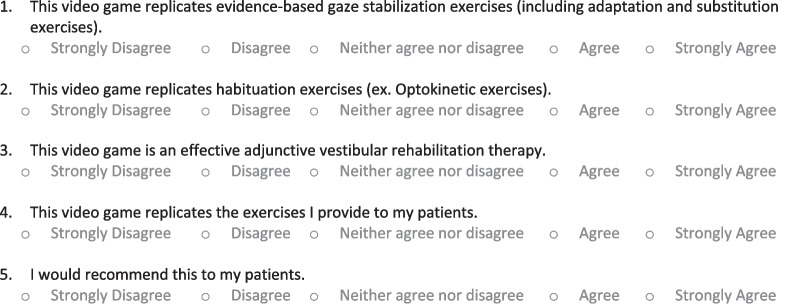

Sample videos of a member of the research team playing the eligible video games along with a screen recording of the video game itself were included in the survey (Fig. 1) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79q7bh3PbsA&ab_channel=AustinHeffernan). Physiotherapists were asked to watch each game and provide a response on a five-point Likert scale to the statements listed in Fig. 2. The five-point Likert-scale responses were scored as follows: strongly disagree (1 point), disagree (2 points), neither agree nor disagree (3 points), agree (4 points), and strongly agree (5 points). Surveys were delivered using the Qualtrics Software, Version 0822 of Qualtrics. Copyright © (2022) Qualtrics (Provo, UT).

Fig. 1.

VR X-Racer and virtual reality tunnel racing and VR real world bike racing games. Anterior view of the user and the point-of-view of the user is displayed

Fig. 2.

Virtual reality video game validation survey

Physiotherapist recruitment

Physiotherapist recruitment was conducted using the Physiotherapy Association of British Columbia (PABC) website. Physiotherapists who self-identified as having training and/or experience in SVR were identified using the PABC website “Find a Physio” function. Eligible physiotherapists who held valid licensure with the College of Physiotherapists of British Columbia, were actively practicing, and who provided SVR were contacted through email to participate in the survey.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24. Medians and interquartile ranges are reported for the scored physiotherapists’ responses to each video game’s survey statement and for global scores. Global scores were calculated for each survey, which is defined as the sum of the scored responses to each survey statement. A Friedman Two-Way ANOVA (a-priori alpha = 0.05) was used to compare the scored physiotherapists’ survey responses given for each of the video games assessed. If a statistically significant difference was identified, a paired samples sign test was used as a post hoc exploratory procedure to identify which video games differ based on the physiotherapists’ responses. Significance values for the sign test were adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests, resulting in a significance level set at p < 0.002.

Results

The search yielded 58 games, of which 4 games met the eligibility criteria, namely VR Tunnel Race (VRTR), VR Real World Bike Racing (VRWBR), Derby VR (DVR) and VR X-Racer (VRXR). A total of 237 physiotherapists were contacted and 40 (17%) consented to complete the survey in full. Survey results indicated that the largest fraction of physiotherapist responses was “agree” for VRXR, DVR, VRTR, and VRWBR replicating gaze stabilization exercises, matching habituation exercises, being effective adjunctive therapies and for recommending these games to their patients (Table 1). Additionally, the largest proportion of physiotherapists agreed that DVR, VRTR and VRWBR replicated physiotherapist prescribed exercises, however physiotherapists opinions on VRXR replicating physiotherapist prescribed exercises were almost evenly divided between disagreed (32.5%) and agreed (30%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey subscale response percentages for each of the four virtual reality video games

| Statement | Game | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

| Replicates gaze stabilization exercises | VRXR | 12.5 | 25 | 15 | 40 | 7.5 |

| DVR | 7.5 | 20 | 10 | 50 | 12.5 | |

| VRTR | 7.5 | 30 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 12.5 | |

| VRWBR | 5 | 15 | 20 | 37.5 | 22.5 | |

| Replicates habituation exercises | VRXR | 0 | 5 | 15 | 60 | 20 |

| DVR | 0 | 5 | 25 | 57.5 | 12.5 | |

| VRTR | 0 | 0 | 10 | 45 | 45 | |

| VRWBR | 0 | 7.5 | 15 | 62.5 | 15 | |

| Effective adjunct therapy | VRXR | 2.5 | 15 | 22.5 | 50 | 10 |

| DVR | 2.5 | 10 | 32.5 | 47.5 | 7.5 | |

| VRTR | 2.5 | 2.5 | 20 | 60 | 15 | |

| VRWBR | 0 | 7.5 | 22.5 | 60 | 10 | |

| Replicates physiotherapist prescribed exercises | VRXR | 12.5 | 32.5 | 25 | 30 | 0 |

| DVR | 5 | 30 | 22.5 | 40 | 2.5 | |

| VRTR | 5 | 25 | 22.5 | 37.5 | 10 | |

| VRWBR | 2.5 | 25 | 17.5 | 45 | 10 | |

| Would you recommend it to your patients? | VRXR | 10 | 12.5 | 30 | 37.5 | 10 |

| DVR | 2.5 | 30 | 27.5 | 32.5 | 7.5 | |

| VRTR | 5 | 17.5 | 20 | 42.5 | 15 | |

| VRWBR | 0 | 15 | 22.5 | 52.5 | 10 | |

DVR Derby Virtual Reality, PT Physiotherapist, VR Virtual Reality, VRTR Virtual Reality Tunnel Racing, VRWBR Virtual Reality Real World Bike Racing, VRXR Virtual Reality X-Racer

Among all four games, Friedman Two-Way ANOVA demonstrated significant differences in gaze stabilization exercise replication (p = 0.013), habituation exercise replication (p < 0.001), effective adjunctive therapy (p = 0.045) and physiotherapist prescribed exercise replication scores (p < 0.001) (Table 2). In terms of collated median global scores, VRTR and VRWBR were tied for the highest median score of 18 (Table 2). Paired samples sign test analysis indicated that VRTR replicated habituation exercises significantly (p < 0.001) better than DVR however VRTR and VRWBR did not differ significantly in their ability to replicate habituation exercises (Table 3). While VRWBR replicated physiotherapist-prescribed exercises significantly (p < 0.001) better than VRXR there was once again no discernable difference between VRWBR and VRTR (Table 3).

Table 2.

Survey subscale median values and confidence intervals for all four virtual reality racing games

| Subscale | VRXR [Median (IQR)] | DVR [Median (IQR)] | VRTR [Median (IQR)] | VRWBR [Median (IQR)] | Friedman’s ANOVA p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicates gaze stabilization exercises | 3.00 (2.00) | 4.00 (2.00) | 3.50 (2.00) | 4.00 (1.00) | 0.013* |

| Replicates habituation exercises | 4.00 (0.00) | 4.00 (1.00) | 4.00 (1.00) | 4.00 (0.00) | < 0.001* |

| Effective adjunctive therapy | 4.00 (1.00) | 4.00 (1.00) | 4.00 (0.25) | 4.00 (1.00) | 0.045* |

| Replicates exercises prescribed by PT | 3.00 (2.00) | 3.00 (2.00) | 3.00 (2.00) | 4.00 (2.00) | < 0.001* |

| Would recommend to patient | 3.00 (1.00) | 3.00 (2.00) | 4.00 (1.00) | 4.00 (1.00) | 0.150 |

DVR Derby Virtual Reality, IQR Interquartile range, PT Physiotherapist, VR Virtual Reality, VRTR Virtual Reality Tunnel Racing, VRWBR Virtual, Reality Real World Bike Racing, VRXR Virtual Reality X-Racer

*A-priori alpha value = 0.05 for Freidman’s Two-Way ANOVA

Table 3.

Post-hoc pairwise sign test results values for all four virtual reality racing games

| Subscale | VRXR (A) versus DVR (B) | VRXR (A) versus VRTR (C) | VRXR (A) versus VRWBR (D) | DVR (B) versus VRTR (C) | DVR (B) versus VRWBR (D) | VRTR (C) versus VRWBR (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicates gaze stabilization exercises | A > B = 4 | C < A = 5 | A > D = 3 | C < B = 10 | D < B = 8 | D < C = 4 |

| A < B = 12 | C > A = 9 | A < D = 17 | C > B = 6 | D > B = 10 | D > C = 11 | |

| Tie = 24 | Tie = 26 | Tie = 20 | Tie = 24 | Tie = 22 | Tie = 25 | |

| p = 0.077 | p = 0.424 | p = 0.003 | p = 0.454 | p = 0.815 | p = 0.118 | |

| Replicates habituation exercises | A > B = 9 | C < A = 3 | A > D = 9 | C < B = 1 | D < B = 4 | D < C = 16 |

| A < B = 2 | C > A = 15 | A < D = 6 | C > B = 19 | D > B = 7 | D > C = 3 | |

| Tie = 29 | Tie = 22 | Tie = 25 | Tie = 20 | Tie = 29 | Tie = 21 | |

| p = 0.065 | p = 0.008 | p = 0.607 | p = < 0.001* | p = 0.549 | p = 0.004 | |

| Effective adjunctive therapy | A > B = 10 | C < A = 7 | A > D = 6 | C < B = 4 | D < B = 5 | D < C = 6 |

| A < B = 7 | C > A = 16 | A < D = 13 | C > B = 13 | D > B = 12 | D > C = 4 | |

| Tie = 23 | Tie = 17 | Tie = 21 | Tie = 23 | Tie = 23 | Tie = 30 | |

| p = 0.629 | p = 0.093 | p = 0.167 | p = 0.049 | p = 0.143 | p = 0.754 | |

| Replicates exercises prescribed by PT | A > B = 5 | C < A = 6 | A > D = 3 | C < B = 11 | D < B = 7 | D < C = 6 |

| A < B = 15 | C > A = 19 | A < D = 22 | C > B = 14 | D > B = 14 | D > C = 9 | |

| Tie = 20 | Tie = 15 | Tie = 15 | Tie = 15 | Tie = 19 | Tie = 25 | |

| p = 0.041 | p = 0.015 | p = < 0.001* | p = 0.690 | p = 0.189 | p = 0.607 | |

| Would recommend to patient | – | – | – | – | – | – |

DVR Derby Virtual Reality, PT Physiotherapist, VR Virtual Reality, VRTR Virtual Reality Tunnel Racing, VRWBR Virtual Reality Real World Bike Racing, VRXR Virtual Reality X-Racer

*A-priori Bonferroni corrected two-tailed p value < 0.002

Discussion

This is the first study that assessed licensed physiotherapists’ opinion on the vestibular rehabilitation potential of commercially available virtual reality videos games. They determined that VRWBR and VRTR were the two VR video games with the highest vestibular rehabilitation potential. Deciding between these two games could not be done based on study results and statistical analyses alone. While this study did not seek to determine user’s preferences for different videogames, their preferences will likely play a large role in treatment adherence, especially for older patients who are known to report reduced usability of new gaming technology [22]. One of the investigators (AH) who tried all videogames assessed, found VRWBR easier to use than VRTR on an iOS device, suggesting that VRWBR is the preferable game of choice for further clinical trial analysis in a cohort of older patients. Virtual reality has previously been shown to improve enjoyment and motivation during vestibular rehabilitation in young and middle-aged adults and thus has the potential to increase treatment adherence [18, 23].

For many chronic peripheral vestibular disorders, it is established that vestibular rehabilitation improves symptom scores and quality of life, however studies comparing the relative importance of gaze stabilization, habituation, and substitution exercises for specific vestibular pathologies are scarce and of poor quality [24, 25]. VRTR, in contrast to VRWBR, lacks the ability to alter the amount of optokinetic stimulation which prevents progressive grading of exercise difficulty, which is considered a therapeutic program requirement for effective recovery [26]. Additionally, this lack of grading could cause it to be visually over stimulating especially in patients who start this treatment soon after the onset of dizziness or vertigo symptoms. This may lead to reduced adherence to virtual reality vestibular therapy. These considerations together suggest that VRWBR is the preferred game of choice for clinical trialling.

Gaze stabilization exercises involve head movements in the vertical plane (pitch) and horizontal plane (yaw) to induce vestibular adaptation and to achieve substitution through enhanced VOR gain [12]. These exercises are used as the foundation of vestibular rehabilitation for bilateral and unilateral vestibular hypofunction [27–29]. In contrast to standard gaze stabilization exercises, both VRWBR and VRTR utilize user pitch head movements and movements in a sagittal plane (roll) to control the game. This difference could result in less effective vestibular substitution due to roll movements eliciting less enhancement in VOR gain [30]. Despite this, the combination of these movements and optokinetic stimulation from VRTR or VRWBR could benefit patients suffering from peripheral vestibular pathologies as the combination of habituation, adaptation and substitution exercises have been shown to elicit maximum benefit [25, 27]. This is evidenced by Micarelli et al. 2017 who demonstrated that a user’s pitch and roll movement based virtual reality video game combined with SVR improved dizziness handicap scores significantly more than SVR alone [19].

The demonstrable differences between some virtual reality programs, and SVR leaves the opportunity for innovation. Recently, a smartphone-based gaming system for vestibular rehabilitation has been developed which consists of two games with graded levels of difficulty that utilize optokinetic stimulation and discrete head movements in the pitch and yaw planes to achieve rehabilitation [31]. The games’ difficulty is determined by a performance-based algorithm [31]. This system was determined to be useable and safe to use in patients with unilateral vestibular dysfunction, however a randomized controlled trial testing its efficacy as an adjunct or sole treatment for chronic peripheral vestibular pathologies is lacking. This gaming system is a preliminary step in the development of an additional and more motivating treatment option for patients diagnosed with a chronic peripheral vestibular disorder. The results of the current study will determine how the assessed localization of vestibular pathology impacts the therapeutic effect of at-home adjunct virtual reality therapy. This will better inform the development and implementation of at-home virtual reality-based treatments for vestibular pathologies.

This study introduces the option of using VRWBR as an adjunctive treatment, however there are limitations to the conclusions drawn. The study by design is unable to provide a robust clinical recommendation for the use of VRWBR. A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial of VRWBR is required to arrive at a robust recommendation. The results are hindered by the lack of validated surveys that assess video games for their vestibular rehabilitation potential. The survey utilized in this study was created by medical students, a neurotologist, and a physiotherapist with a special interest in vestibular rehabilitation and was not subjected to validation testing prior to its use. The physiotherapists based their assessments on video recordings of an individual playing each video game; they did not personally use each video game. It is uncertain how this affects the accuracy of their responses. The licensed physiotherapists surveyed were recruited through the PABC website where physiotherapists can self-select interest/training areas. No attempt was made to select physiotherapists based on objective measures of vestibular education, knowledge, or documented experience. The low response rate is however likely a reflection of participant physiotherapists self selection as Balance and Dizziness Canada lists only 28 therapists in British Columbia who have completed at least one competency-certified formal exam or have taken multiple in-person post-professional courses without formal exams [32]. Future studies that survey objectively verified vestibular physiotherapists using a validated virtual reality video game questionnaire and that provides respondents with direct exposure to the games are needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, according to the opinions of licensed physiotherapists, VRTR and VRWBR are the most congruent VR video games to SVR. These video games replicate both habituation and gaze stabilization exercises, could be effective adjunctive therapies to vestibular rehabilitation and would be recommended by physiotherapists to their patients. VRWBR is preferable to VRTR with respect to ease of use and the ability to alter the amount of optokinetic stimulation. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of these videos games and to determine if they could be used as solitary treatments. These games could lay the foundation for the development of virtual reality video games that replicate vestibular rehabilitation exercises.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Reyhaneh Abgoon for assistance with administrative tasks.

Abbreviations

- DVR

Derby VR

- HMD

Head mounted display

- PABC

Physiotherapy Association of British Columbia

- SVR

Standard vestibular rehabilitation

- VR

Virtual reality

- VOR

Vestibular ocular reflex

- VRTR

VR Tunnel Race

- VRWBR

VR Real World Bike Racing

- VRXR

VR X-Racer

Author contributions

The senior author conceptualized the work and contributed to study design and manuscript preparation. The third author contributed to manuscript preparation. The second author contributed to protocol development, data extraction and manuscript approval. The first author conceptualized the work and contributed to data extraction, data analysis and prepared manuscript drafts.

Funding

The authors report no sources of funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (H21-01535) as part of a larger clinical trial. Informed consent was received prior to survey completion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hülse R, Biesdorf A, Hörmann K, Stuck B, Erhart M, Hülse M, et al. Peripheral vestibular disorders: an epidemiologic survey in 70 million individuals. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(1):88–95. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang T, Xirasagar S, Cheng Y, Wu C, Kuo N, Lin H. Peripheral vestibular disorders: nationwide evidence from Taiwan. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(3):639–643. doi: 10.1002/lary.28877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitney SL, Herdman SJ. Physical therapy assessment of vestibular hypofunction. 35.

- 4.Hilber P, Cendelin J, Le Gall A, Machado ML, Tuma J, Besnard S. Cooperation of the vestibular and cerebellar networks in anxiety disorders and depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;89:310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon N, Pollack M, Tuby K, Stern T. Dizziness and panic disorder: a review of the association between vestibular dysfunction and anxiety. Ann of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;10(2):75–80. doi: 10.3109/10401239809147746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall CD. Vestibular rehabilitation for peripheral vestibular hypofunction: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.McDonnell MN, Hillier SL. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane ENT Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2015 Jan 13 [cited 2020 Nov 27]; 10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Herdman SJ. Treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Phys Ther. 1990 doi: 10.1093/ptj/70.6.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert MC, Migliaccio AA, Clendaniel RA, Allak A, Carey JP. Mechanism of dynamic visual acuity recovery with vestibular rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herdman SJ. Advances in the treatment of vestibular disorders. Phys Ther. 1997;77(6):602–618. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.6.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brewer BW. Adherence to sport injury rehabilitation programs. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1998;10(1):70–82. doi: 10.1080/10413209808406378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen PY, Hsieh WL, Wei SH, Kao CL. Interactive wiimote gaze stabilization exercise training system for patients with vestibular hypofunction. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil. 2012;9(1):77. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maggio MG, Latella D, Maresca G, Sciarrone F, Manuli A, Naro A, et al. Virtual reality and cognitive rehabilitation in people with stroke: an overview. J Neurosci Nurs. 2019;51(2):101–105. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia AP, Ganança MM, Cusin FS, Tomaz A, Ganança FF, Caovilla HH. Vestibular rehabilitation with virtual reality in Ménière’s disease. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79(3):366–374. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20130064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu SY, Fang TY, Yeh SC, Su MC, Wang PC, Wang VY. Three-dimensional, virtual reality vestibular rehabilitation for chronic imbalance problem caused by Ménière’s disease: a pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(16):1601–1606. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1203027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlou M, Kanegaonkar RG, Swapp D, Bamiou DE, Slater M, Luxon LM. The effect of virtual reality on visual vertigo symptoms in patients with peripheral vestibular dysfunction: a pilot study. J Vestib Res. 2012;22(5,6):273–281. doi: 10.3233/VES-120462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergeron M, Lortie CL, Guitton MJ. Use of virtual reality tools for vestibular disorders rehabilitation: a comprehensive analysis. Advances in Medicine. 2015;2015:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2015/916735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heffernan A, Abdelmalek M, Nunez DA. Virtual and augmented reality in the vestibular rehabilitation of peripheral vestibular disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17843. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97370-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micarelli A, Viziano A, Augimeri I, Micarelli D, Alessandrini M. Three-dimensional head-mounted gaming task procedure maximizes effects of vestibular rehabilitation in unilateral vestibular hypofunction: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Int J Rehabil Res. 2017;40(4):325–332. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Micarelli A, Viziano A, Micarelli B, Augimeri I, Alessandrini M. Vestibular rehabilitation in older adults with and without mild cognitive impairment: effects of virtual reality using a head-mounted display. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;83:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong K, Yee HM, Xavier BA, Grillone GA. Applications of augmented reality in otolaryngology: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(6):956–967. doi: 10.1177/0194599818796476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller KJ, Adair BS, Pearce AJ, Said CM, Ozanne E, Morris MM. Effectiveness and feasibility of virtual reality and gaming system use at home by older adults for enabling physical activity to improve health-related domains: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(2):188–195. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meldrum D, Herdman S, Vance R, Murray D, Malone K, Duffy D, et al. Effectiveness of conventional versus virtual reality-based balance exercises in vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular loss: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(7):1319–1328.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Esch BF, van der Scheer-Horst ES, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Bruintjes TD, van Benthem PPG. The effect of vestibular rehabilitation in patients with Ménière’s disease: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(3):426–434. doi: 10.1177/0194599816678386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma KG, Gupta AK. Efficacy and comparison of vestibular rehabilitation exercises on quality of life in patients with vestibular disorders. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;72(4):474–479. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01920-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han BI, Song HS, Kim JS. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy: review of indications, mechanisms, and key exercises. J Clin Neurol. 2011;7(4):184. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2011.7.4.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall CD, Herdman SJ, Whitney SL, Anson ER, Carender WJ, Hoppes CW, et al. Vestibular rehabilitation for peripheral vestibular hypofunction: an updated clinical practice guideline from the academy of neurologic physical therapy of the American physical therapy association. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2022;46(2):118–177. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabrera Kang C, Tusa R. Vestibular rehabilitation: rationale and indications. Semin Neurol. 2013;33(03):276–285. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1354593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermann R, Pelisson D, Dumas O, Urquizar C, Truy E, Tilikete C. Are covert saccade functionally relevant in vestibular hypofunction? Cerebellum. 2018;17(3):300–307. doi: 10.1007/s12311-017-0907-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herdman SJ. Role of vestibular adaptation in vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nehrujee A, Vasanthan L, Lepcha A, Balasubramanian S. A Smartphone-based gaming system for vestibular rehabilitation: a usability study. VES. 2019;29(2–3):147–160. doi: 10.3233/VES-190660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrea Wilson (2022). Practitioners List [Internet]. Balance & Dizziness Canada. https://balanceanddizziness.org/diagnosis-and-treatment/other-health-professionals/practitioners-list/?fwp_location=bc_lower_mainland&fwp_paged=2&fbclid=IwAR1jdvWll0tycXiyoqSqfOlSBkXnM96piJgGFgd4UarAXJ1kqvsCmplqPWc

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.