Abstract

In many cases of neurological disease associated with viral infection, such as measles virus (MV)-induced subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in children, it is unclear whether the virus or the antiviral immune response within the brain is the cause of disease. MV inoculation of transgenic mice expressing the human MV receptor, CD46, exclusively in neurons resulted in neuronal infection and fatal encephalitis within 2 weeks in neonates, while mice older than 3 weeks of age were resistant to both infection and disease. At all ages, T lymphocytes infiltrated the brain in response to inoculation. To determine the role of lymphocytes in disease progression, CD46+ mice were back-crossed to T- and B-cell-deficient RAG-2 knockout mice. The lymphocyte deficiency did not affect the outcome of disease in neonates, but adult CD46+ RAG-2− mice were much more susceptible to both neuronal infection and central nervous system disease than their immunocompetent littermates. These results indicate that CD46-dependent MV infection of neurons, rather than the antiviral immune response in the brain, produces neurological disease in this model system and that immunocompetent adult mice, but not immunologically compromised or immature mice, are protected from infection.

The restriction of immune function within the brain due to the presence of the blood brain barrier, a lack of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression, and an absence of lymphatic drainage has led to the presumption that the central nervous system (CNS) is a site of immune privilege (7, 37, 43). However, it is clear that activated leukocytes and immune mediators can access the brain (18, 47) and that inflammatory responses are associated with numerous CNS disorders, including multiple sclerosis (9), Alzheimer’s disease (31), and many neurotropic viral infections (26, 36, 39, 46, 48). While the antiviral immune response may help control infection in the CNS, often it is this response, rather than the infection alone, that results in disease. How the balance between neuroprotection and immunopathogenesis is regulated in the CNS remains an unresolved, yet clinically relevant issue.

Measles virus (MV) is a member of the paramyxovirus family which causes an acute infection in humans and primates; usually the acute disease is resolved uneventfully with lifelong immunity. However, in rare cases, mostly in children, MV can persistently infect neurons and oligodendrocytes within the CNS, leading to the progressive and fatal CNS disease subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) (4, 17, 21, 45). SSPE often begins months to years after the acute infection, and postmortem specimens reveal massive CNS damage, including cell death and astrogliosis (4, 11, 25). In addition, lymphocyte infiltration of the brain and high titers of MV-specific antibodies are found in SSPE; yet whether the immune response is involved in disease progression remains unresolved (4, 11). The basis for these MV-associated CNS diseases is unclear, and the role which the host immune response plays in either neuroprotection or disease is not understood. Interestingly, a study of random autopsy brain tissues showed evidence of MV in the brains of 20% of adults who never showed symptoms of CNS disease (24). These data raise the possibility that measles infection of the brain does not invariably lead to CNS disease or that CNS disease mediated by MV is age dependent.

Although small animal models of MV infection of the CNS exist (2, 19, 28), these systems use rodent-adapted strains of measles whose sequence, cell tropism, receptor usage, and extracellular virus production differ markedly from wild-type infection of the CNS (28, 29, 40). To more closely parallel the human CNS infection caused by measles, we established a transgenic mouse model system in which the human high-affinity measles virus receptor, CD46 (12, 33), was expressed under the transcriptional control of the neuron-specific enolase promoter (38). Intracerebral infection of NSE-CD46 transgenic mice with MV-Edmonston, a CD46-dependent vaccine strain of measles, produced severe CNS disease associated with extensive neuronal infection in neonates, yet adult transgenic mice were resistant to both infection and disease (38). Importantly, while virus clearly replicates and spreads within the CNS of transgenic neonates, no infectious virus can be isolated from infected brains, a phenomenon that is a hallmark feature of SSPE (25).

In this study, a genetic approach was taken to determine the contribution of the immune response to disease progression in infected neonatal and adult transgenic mice. The data indicate that the adult immune response, but not the neonatal response, can protect mice from both infection and disease. Furthermore, the abrogation of this immune response in adults leads to infection and CNS disease similar to that in neonates. The implications of this work for measles infection of the human CNS are discussed, and it is suggested that host factors, including immunocompetence and postnatal age when infected, are major determinants in the outcome of chronic neurotropic infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were obtained from the closed breeding facility of The Fox Chase Cancer Center. All mice were maintained in conditions consistent with the facility animal care regulations (AAALAC) throughout the course of investigation.

The establishment of transgenic mice expressing the human MV receptor, CD46, in CNS neurons has been described previously (38). Transgenic mice were identified by hybridization of tail DNA to a transgene-specific 32P-labeled probe. DNA was isolated from a tail biopsy and 10 μg was transferred onto a nylon filter (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.). Mice from two independently derived lineages (lines 18 and 52) were used in these experiments; data presented are from line 18 transgenic mice unless otherwise indicated. RAG-2 knockout mice (H-2b) were a generous gift of F. W. Alt (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Boston, Mass.).

Homozygous NSE-CD46+ and homozygous RAG-2−/− mice were intercrossed for two generations. RAG-2−/− progeny were identified by flow cytometry on peripheral blood lymphocytes stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies to mouse CD4 and CD8 antigens. In some cases, the RAG-2 genotype was confirmed by postmortem immunohistochemical staining of frozen spleen sections with antibodies specific for B- and T-lymphocyte markers.

Virus and infection of mice.

All mice were infected with the specified doses of MV-Edmonston (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.). This virus was amplified three times in Vero fibroblasts. The inoculum was diluted as needed in phosphate-buffered saline and administered intracerebrally to metofane-anesthetized mice along the midline, in a volume of 10 μl (for neonates) and 30 μl (for adults) with a 27-gauge needle.

Northern blot analysis of CD46 mRNA expression.

Organs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until homogenized with a Virtishear (Virtis, Gardiner, N.Y.) for 30 s in 1 ml of Tri-Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per 100 mg of tissue. For Northern blot analysis of CD46 expression, 10-μg samples of purified total RNA were denatured and run on a 1% agarose formaldehyde gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, UV cross-linked, and hybridized overnight at 65°C with 32P-labeled probes specific for either CD46 or GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). DNA fragments were labeled with the Prime-It II random hexamer labeling kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and probes with specific activities of at least 5 × 108 cpm/μg were used.

Immunohistochemical analysis of mouse tissues.

Organs were snap-frozen in dry ice-isopentane and stored at −70°C. Horizontal cryosections (10 μm) were air dried and stored at −70°C. On the day of staining, sections were fixed in ice-cold 95% ethanol and blocked for 20 min with 2% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) for MV staining, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for CD4 and CD8 T-cell staining, or 2% calf serum (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) for B-cell staining. Avidin and biotin were used for blocking when required (Vector Laboratories). Primary antibodies (incubated for 2 h at room temperature, diluted in blocking buffer as indicated) included human SSPE immune serum Vasquez (1:750) for MV, clone RM4-5 rat anti-mouse CD4 (1:50), clone 53-6.7 rat anti-mouse CD8α plus clone 53-5.8 rat anti-mouse CD8β (1:50 each), and clone RA3-6B2 rat anti-mouse CD45R/B220 (1:1,000 for B cells) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Secondary antibodies (incubated for 1 h at room temperature, 1:200 dilution in blocking buffer) included biotinylated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) for MV staining and biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG for CD4, CD8, and B-cell staining (Vector Laboratories). All sections were peroxidase labeled with the ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories) and 0.7 mg of diaminobenzidine per ml in 60 mM Tris buffer with 1.6 mg of H2O2 per ml (Sigma). Uninfected tissues or omission of the primary antibody served as negative controls.

RESULTS

Host age and susceptibility to MV-induced CNS disease are inversely correlated.

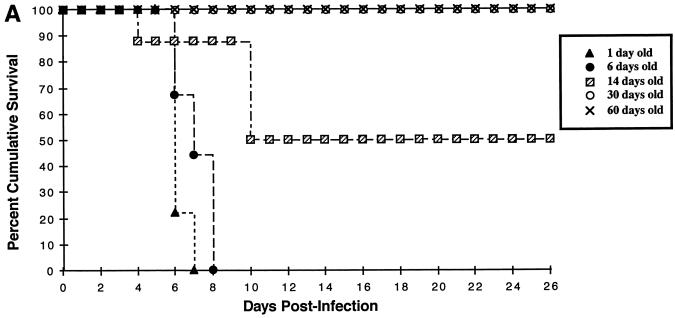

We previously reported (38) that intracerebral (i.c.) infection of NSE-CD46+ neonatal mice with 105 PFU of MV-Edmonston caused extensive neuronal infection, CNS disease, and death. Conversely, inoculation of transgenic adults (greater than 4 weeks of age) failed to induce illness (38). To further define the age dependence of susceptibility to MV-induced disease, several litters of homozygous NSE-CD46+ mice at various ages were inoculated i.c. with 3 × 104 PFU of MV-Edmonston. As indicated in Fig. 1A, mice inoculated on postnatal day 1 or day 6 showed the fastest kinetics of disease, with all mice dead by 7 to 8 days postinfection. Signs of CNS disease (tremors, ataxia, a hunched appearance, and paralysis) appeared 1 to 2 days prior to death. None of the mice inoculated at 30 days or older showed signs of disease, and all of them survived. Importantly, when mice were inoculated at 14 days of age, only 50% of mice showed signs of disease, and the average onset of disease was delayed until 10 days postinfection. In each age group, there were no differences in outcome between male and female mice (data not shown). Figure 1B shows that, in transgenic mice, CD46 mRNA expression in the brain is maintained in adult mice, suggesting that the lack of MV-induced disease in adults is not likely due to downregulation of receptor expression.

FIG. 1.

(A) Neuronal MV infection is lethal only in neonatal mice. Homozygous line 18 NSE-CD46+ mice, from 1 day to 60 days of age, were inoculated i.c. with 3 × 104 PFU of MV-Edmonston and monitored daily for disease and death. Data represent the percent survival within each group of 7 to 9 mice. Similar results were obtained in at least two additional experiments for each age group and in line 52 mice. (B) CD46 mRNA expression is maintained into adulthood in transgenic mice. Total mRNA was isolated from brains of NSE-CD46 transgenic mice as described in Materials and Methods. Northern blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled probes specific for either CD46 (upper panel) or GAPDH (lower panel). For each age group, two mice were tested in separate lanes as follows: e16, embryonic day 16; p1, postnatal day 1; p3, postnatal day 3; p10, postnatal day 10; and p23, postnatal day 23.

MV-induced neurological disease in NSE-CD46+ transgenic mice is dose dependent.

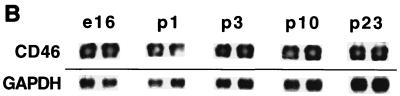

To assess the minimum dose of virus needed to produce CNS disease in neonates, 5-day-old homozygous NSE-CD46+ mice (line 18) were infected i.c. with various doses (30 to 3 × 104 PFU) of MV-Edmonston in a constant volume (10 μl). All neonates inoculated with the two highest doses of MV died by 8 days postinfection (Fig. 2). At the 300-PFU dose, 5 of 6 infected mice succumbed to MV infection, with a time course of disease similar to the higher doses. Only at the lowest dose, 30 PFU, were the kinetics of mortality slower and more variable; death occurred in 66% of inoculated mice between 8 and 14 days postinfection, although 100% of the animals showed signs of illness, suggesting that some of these mice were infected but recovered. Adult mice showed no disease signs with infectious doses 3,000-fold higher than that required to cause disease in neonates, indicating that differences in brain volume cannot account for the age difference in susceptibility to MV-induced CNS disease and death (data not shown). These data, together with the age-dependent susceptibility to illness (Fig. 1A), indicate that the outcome of CNS infection represents a balance of multiple factors, including viral dose, host age, and possibly immunocompetence.

FIG. 2.

Lethality of neuronal MV infection is dose dependent. Five-day-old homozygous line 18 NSE-CD46+ mice were inoculated i.c. with 30 to 3 × 104 PFU of MV-Edmonston. The mice were monitored daily for evidence of disease (tremors, seizures, paralysis, and weight loss), and mortality was recorded. Data represent the percent survival within each group of five to six mice.

The kinetics of disease onset and death in transgenic neonates were highly reproducible, with either heterozygous and homozygous mice from independently derived lines 18 and 52, and no signs of illness were observed in either nontransgenic mice or transgenic neonates infected with UV-inactivated virus (data not shown).

Neuronal MV infection and immune response in neonates versus adults.

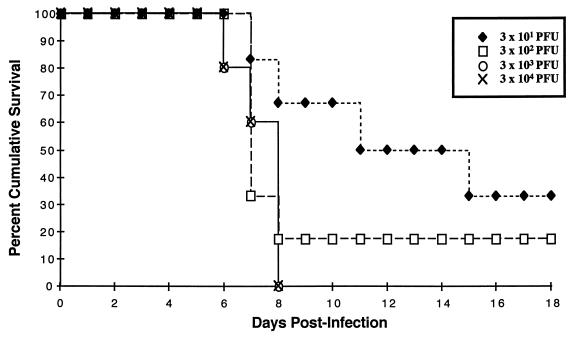

We next examined whether there were age differences in neuronal infection and the immune response to infection. Since extracellular MV could not be detected in infected brains (38), we used immunohistochemical analysis to compare viral protein expression, as well as T- and B-cell infiltration in brains from infected neonates (5 to 6 days of age) and adults (45 to 60 days of age), at two time points. Figure 3 shows representative micrographs of MV, CD4, and CD8 staining; Table 1 presents a quantification of infected cells and infiltrating lymphocytes in at least four mice from multiple levels throughout the brain.

FIG. 3.

Time course of MV infection and CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte infiltration in brains of neonates and adult NSE-CD46+ mice. Homozygous line 18 mice were inoculated as neonates (5 to 6 days old) or adults (45 to 60 days old) and sacrificed at either 3 or 6 days postinfection. Frozen brain sections from these mice were peroxidase stained for MV antigen (A, D, G, and J; ×40), CD4+ T lymphocytes (B, E, H, and K; ×100), and CD8+ T lymphocytes (C, F, I, and L; ×100) as described in Materials and Methods. Panels: A to C, neonatal brain, 3 days postinfection; D to F, neonatal brain, 6 days postinfection; G to I, adult brain, 3 days postinfection; J to L, adult brain, 6 days postinfection.

TABLE 1.

Quantification of neuronal MV infection and lymphocyte infiltration in neonate and adult micea

| Days p.i. | Site | Neonates (5 to 6 days)

|

Adults (45 to 60 days)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV | CD4+ | CD8+ | MV | CD4+ | CD8+ | ||

| 3 | Parenchyma | ++ | + | − | − | ++ | + |

| Meninges and ventricles | − | ++ | − | − | ++ | + | |

| 6 | Parenchyma | +++ | ++ | + | − | +++ | +++ |

| Meninges and ventricles | − | ++ | + | − | +++ | +++ | |

At least four mice each of neonatal and adult line 18 NSE-CD46+ mice were inoculated i.c. with 3 × 104 PFU MV-Edmonston. After 3 or 6 days postinfection, mice were sacrificed and brains were collected for cryostat sectioning. Frozen brain sections from each mouse were stained as described in Fig. 3 and in Materials and Methods. Positively labeled cells were counted over the entire section, and assigned to a range as follows: −, 0 to 10 cells; +, 11 to 50 cells; ++, 51 to 250 cells; +++, >250 cells. The data shown are average results from multiple levels of at least two brains per group. Similar results were obtained with line 52 transgenic mice.

By 3 days postinfection, all neonates and adults appeared healthy: body weight, activity level, and limb mobility were normal. MV antigen was detected in neonatal brains (Fig. 3A) but very rarely in adults (Fig. 3G). Patches of focal infection in neonates appeared in the hippocampus, cortex, inferior colliculus, and paraventricular regions and occasionally in the Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum. At 6 days postinfection, adults remained healthy but, consistent with the survival studies described above, most of the neonates showed signs of CNS disease. The magnitude of infection in neonates had increased by this time (Fig. 3D, Table 1) but still was not apparent in adults (Fig. 3J, Table 1). Replicating virus, viral RNA, and viral proteins were never detected in nonneuronal tissues by plaque assay, Northern blot analysis, and immunohistochemistry, respectively (data not shown). Thus, the neuronal infection progressed over time in neonates but not in adults, and CNS disease signs only occurred in mice with neuronal MV infection. The lack of infection in adults could be explained either by a resistance of the adult neurons to infection or by rapid clearance of MV from the infected CNS.

In contrast to the age difference in neuronal infection, T lymphocytes were detected in the brains of mice at any age (Fig. 3B and C, E and F, H and I, and K and L) for several weeks after inoculation. In most cases, CD4+ cells were more abundant than CD8+ cells, and the numbers of both T-cell subsets increased over time in neonatal and adult brain (Table 1). The magnitude of the antiviral T-lymphocyte infiltration in adults was greater than in neonates at both time points (Table 1). B cells were never detected in brain tissue after inoculation (data not shown). Inoculation of nontransgenic neonates, as well as UV-inactivated virus inoculation of transgenic neonates, produced no T-cell infiltration within the brain (data not shown). Thus, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte infiltration of neonatal brains occurred in response to neuronal MV infection rather than as a general inflammatory response to i.c. inoculation. These results demonstrate that both adult and neonatal mice are infected but that viral spread and subsequent CNS disease occur only in neonates.

T lymphocytes protect against MV-induced disease in adults but not in neonates.

Although T lymphocytes infiltrated the brain in response to neuronal infection at all ages, it was unclear whether lymphocytes played any role in disease progression. If so, differences must exist between the neonatal and adult T-cell response: either neonatal lymphocytes contribute to disease signs or the adult lymphocyte response prevents disease. To establish the role of lymphocytes in MV-induced CNS disease, NSE-CD46+ mice were backcrossed for two generations to RAG-2−/− mice, which lack mature T and B cells due to a deletion of recombination activating gene-2 (3). The resulting F2 litters consisted of four genotype combinations: transgenic immunocompetent (CD46+/−, RAG-2+/−), transgenic lymphocyte deficient (CD46+/−, RAG-2−/−), nontransgenic immunocompetent (CD46−/−, RAG-2+/−), and nontransgenic lymphocyte deficient (CD46−/−, RAG-2−/−). These litters were infected at various ages and monitored daily; scoring of sickness was completed without prior knowledge of each mouse’s genotype. Mice were sacrificed when they showed signs of disease, and brain tissue was analyzed by immunohistochemistry for MV antigen, as well as for CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes. Mice that did not become sick were sacrificed at 3 to 5 weeks postinfection. As expected, none of the nontransgenic mice became sick; the summary for NSE-CD46+ mice, both RAG-2+/− and RAG-2−/−, is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Age dependence of lymphocyte protection from MV-induced CNS diseasea

| Genotype | No. sick/total no. (%) at age of MV inoculationb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonate (1 to 3 days) | Adolescent (11 to 17 days) | Adult (26 to 80 days) | |

| CD46+ RAG2+ | 13/15 (87) [6.2 ± 0.6 days] | 3/6 (50) [9.5 ± 1.4 days] | 0/10 (0) [NA] |

| CD46+ RAG2− | 10/11 (91) [7.2 ± 0.5 days] | 11/13 (85) [16.0 ± 2.0 days] | 10/14 (71) [19.3 ± 2.3 days] |

NSE-CD46+/+ mice were backcrossed two generations with RAG-2−/− mice, and the resulting litters were inoculated at various ages with 3 × 104 PFU of MV-Edmonston. Mice were monitored daily for the onset of CNS disease (tremors, seizures, paralysis, and weight loss). Mice that appeared close to death were sacrificed, and tissues were collected for analysis of genotype, as well as for immunohistochemical analysis of brain tissue. Mice which did not become sick were sacrificed 3 to 4 weeks postinfection. Data shown for NSE-CD46+/−, RAG-2+/− (immunocompetent), and NSE-CD46+/−, RAG-2−/− (lymphocyte-deficient) mice represent the mean time to disease in mice that became sick.

The mean age of disease onset ± the standard error of the mean is shown in brackets.

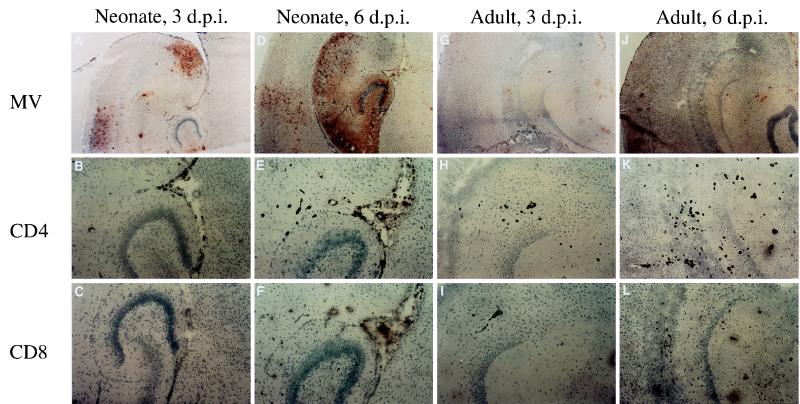

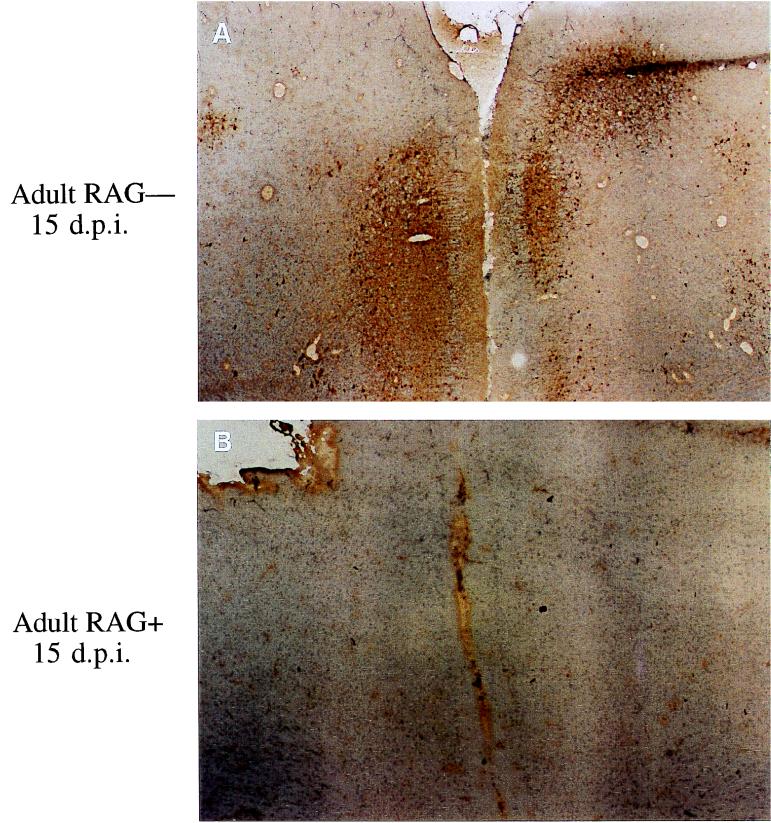

RAG-2+/− and RAG-2−/− neonates developed CNS disease with the same kinetics. However, unlike the immunocompetent mice, most of the “adolescents” (infected at 11 to 17 days of age) and adults (infected at >26 days of age) in the RAG-2−/− category also became moribund (Table 2). Immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections from RAG-2−/− adolescent and adult mice showed extensive neuronal MV infection (Fig. 4A), which was not detected in age-matched RAG-2+/− mice (Fig. 4B) or surviving RAG-2−/− mice. These results confirm that neuronal MV infection, and not the presence of an antiviral response within the brain, is directly associated with CNS disease. In addition, these studies show that an intact immune system provided protection from this infection in adults but not in neonates. Finally, comparison of RAG-2−/− mice of different ages showed a delayed disease onset and enhanced survival in adolescent and adult mice compared to neonates (Table 2). This observation suggests that other factors, in addition to the lymphocyte-mediated protection in adults, such as components of the innate immune response or the developmental status of the brain, also contribute to the pathogenesis of MV-induced CNS disease.

FIG. 4.

MV infection in RAG-2−/− versus immunocompetent adult transgenic mice. F2 litters of CD46 mice backcrossed to RAG-2−/− mice were inoculated as adults and sacrificed at 15 days postinfection. Frozen brain sections from these mice were peroxidase stained for MV antigen. Panels: A, RAG-2−/− adult, showing signs of CNS disease; B, immunocompetent, healthy adult.

DISCUSSION

Three conclusions can be drawn from the work presented here. (i) MV-Edmonston inoculation of NSE-CD46 transgenic mice produces a dose-dependent, CD46-dependent neuronal infection with concomitant CNS disease and death in neonates but not in immunocompetent adults. (ii) CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltrate the brain parenchyma in response to neuronal measles infection at all ages. (iii) Lymphocyte-deficient NSE-CD46 transgenic adult mice are susceptible to neuronal MV infection and disease. Thus, although the immune response contributes to CNS disease in other model systems of neurotropic viral infections (18, 20, 30, 47), in this model of neuronal MV infection, T cells appear to serve a solely beneficial function in adult mice.

Our genetic approach for evaluating the role of the lymphocyte response in neuropathology after MV infection of the brain employed RAG-2−/− mice, which are deficient in both T and B cells (3). Based on our immunohistochemical findings, it is unlikely that B-cell responses are involved in the protection in transgenic adults, since no B cells enter the brain after infection, and in humans and in mouse models of MV encephalitis the antibody response to MV infection is too slow to prevent infection by 3 days, as observed in our adult mice (17, 28). Our finding that only T cells enter the brain parenchyma also supports the hypothesis that infection leads to specific infiltration of T lymphocytes; if a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier were responsible for lymphocyte entry into the brain, intraparenchymal B cells would be expected as well. Thus, the T-lymphocyte response, consisting of CD4+ helper T cells and/or CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, is responsible for the protection of adult mice.

In general, human and mouse lymphocytes are thought to be functionally immature at birth (5, 32), so it was surprising to see any immune response in the brains of infected neonatal mice. However, recent studies have shown that neonatal immune responses can be raised but may require extra stimulation and are biased toward a Th2 cytokine profile (1, 27), leaving neonates potentially more susceptible to infections which can be controlled in adults by a Th1 response. This concept is applicable to the CNS in that gamma interferon, a Th1 cytokine, is critical for resistance to a number of neurotropic viral infections (13, 14). It is unclear whether the Th1-Th2 balance is involved in the protection from measles infection in our model system, but our results suggest that age differences in either the magnitude or the function of the antiviral lymphocyte response, possibly cytokine production or the cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) response, may explain the age dependence of susceptibility to neuronal MV infection. Cytotoxic T cells are needed for protection against a number of neurotropic infections, including those caused by HSV-1 (34) and mouse-adapted strains of MV (35). CTL recognition of viral antigen requires MHC class I expression, which is generally thought to be absent in neurons (23); however, there is evidence for upregulation of class I expression in neurons of SSPE patients and in a rat model of experimental subacute measles encephalitis (15), as well as in mouse neuroblastoma cells persistently infected with measles virus (16). Current studies in our laboratory with NSE-CD46+ mice backcrossed with β2-microglobulin−/− mice will help to elucidate the roles of MHC class I and CTL in response to neuronal measles infection.

If there are no age differences found in the antiviral immune response to infection, an alternative hypothesis to explain the age dependence of susceptibility is that the neonatal response is functionally indistinguishable from the adult response but that viral spread within the neonatal CNS may occur more rapidly than the neonatal immune response can clear virus, shifting the balance in favor of viral replication. Adoptive-transfer experiments of adult T cells into virally infected neonates would help establish whether the “adult” response can protect infected neonates. If so, this would further support the concept that the outcome of a viral infection is predicated on the interaction of multiple factors, including viral replication rate, mechanism of cell-to-cell spread, tissue type infected, host age, and host immunocompetence.

In RAG-2−/− mice, there was a difference between neonates and adults in the percentage of mice experiencing disease signs (91 versus 71%, respectively) and in the latency of disease onset (7 versus 19 days postinfection, respectively) (Table 2). In addition, the number of infected neurons was significantly reduced in adult mice compared to neonates by as early as 3 days postinfection (Table 1). Thus, some factor other than lymphocyte-mediated protection delays disease progression in adults and allows more mice to survive. This factor may be a component of the innate immune system which is intact in the RAG-2−/− mice, such as natural killer cell cytotoxicity or inflammatory cytokine secretion by macrophages or microglia. Alternatively, brain developmental factors or age differences in neuronal function may affect the rate of viral replication and/or spread within the CNS. Neuronal maturation has been implicated in age-dependent outcomes of other CNS infections, such as hamster-adapted MV infection of neurons in mice (41), reovirus encephalitis in mice (44), and encephalomyocarditis virus infection in rat brain (22). Finally, we need to consider the possibility that the CNS disease in neonates and immunocompromised adult mice may be different and that the difference in disease kinetics reflects the distinct pathogeneses of these infections. In support of this hypothesis, preliminary data from our laboratory suggest that the adult RAG-2−/− spinal cord, but not the neonatal spinal cord, is susceptible to infection; whether spinal cord lesions such as demyelination influence the adult disease remains to be determined.

SSPE, the human disease associated with protracted MV infection of CNS neurons, is a very rare disease of children. Interestingly, very few adults have been diagnosed with SSPE, despite extensive acute measles infections in people of all ages. Sequence analysis of viral RNA isolated from brain biopsies of children with SSPE has revealed a large number of point mutations within the envelope-associated genes (6, 8, 10, 42), and it has been proposed that these viral mutants may be either more neurotropic or neuropathogenic than wild-type strains. While we are currently testing the effects of neuronal infection by wild-type strains of MV, in our model system infection of the adult or neonatal CNS by the vaccine strain MV-Edmonston was sufficient to cause disease. Protection from infection and disease was conferred by a mature and competent lymphocyte response. Perhaps the association of SSPE with MV infection in children is not due to an age-dependent access of the virus to the CNS or to the selection for neurotropic or neurotoxic viral variants but rather to the ability of the host immune response to appropriately recognize and resolve neuronal infection. Future studies should take into account the contribution of both immune and CNS developmental differences in the pathogenesis of measles and other neurotropic viral infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants MH56951 and CA06927, as well as by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship, T32-AI07429 (D.M.P.L.), and a grant from the Kirby Foundation (G.F.R.).

We wish to thank Frederick Alt for providing RAG-2 knockout mice, Sarah Berman for secretarial assistance, and Mari Manchester, Michael B. A. Oldstone, Bill Mason, Erica Golemis, Dave Wiest, and John Taylor for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins B, Ghanei A, Hamilton K. Developmental regulation of IL-4, IL-2 and IFN-gamma production by murine peripheral T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:6617–6626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht P, Schumacher H P. Neurotropic properties of measles virus in hamsters and mice. J Infect Dis. 1971;124:86–93. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alt F W, Rathbun G, Oltz E, Taccioli G, Shinkai Y. Function and control of recombination-activating gene activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;651:277–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anlar B. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: diagnosis and drug treatment options. CNS Drugs. 1997;7:111–120. doi: 10.2165/00023210-199707020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvin A M. Viral infections of the fetus and neonate. In: Nathanson N, editor. Viral pathogenesis. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 801–814. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baczko K, Liebert U G, Billeter M, Cattaneo R, Budka H, ter Meulen V. Expression of defective measles virus genes in brain tissues of patients with SSPE. J Virol. 1986;59:472–478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.472-478.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartlett P F, Kerr R S C, Bailey K A. Expression of major histocompatibility antigens in the central nervous system. Transplant Proc. 1989;21:3163–3165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billeter M A, Cattaneo R, Spielhofer P, Kaelin K, Huber M, Schmid A, Baczko K, ter Meulen V. Generation and properties of measles virus mutations typically associated with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;724:367–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb38934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosnan C F, Raine C S. Mechanisms of immune injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:243–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cattaneo R, Schmid A, Eschle D, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Billeter M A. Biased hypermutation and other genetic changes in defective measles viruses in human brain infections. Cell. 1988;55:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90048-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhib-Jalbut S, Johnson K P. Measles virus diseases. In: McKendall R R, Stroop W G, editors. Handbook of neurovirology. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 539–554. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorig R E, Marcil A, Chopra A, Richardson C D. The human CD46 molecule is a receptor for measles virus (Edmonston strain) Cell. 1993;75:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finke D, Brinckmann U G, ter Meulen V, Liebert U G. Gamma interferon is a major mediator of antiviral defense in experimental measles virus-induced encephalitis. J Virol. 1995;69:5469–5474. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5469-5474.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger K D, Nash T C, Sawyer S, Krahl T, Patstone G, Reed J C, Krajewski S, Dalton D, Buchmeier M J, Sarvetnick N. Interferon-gamma protects against herpes simplex virus type 1-mediated neuronal death. Virology. 1997;238:189–197. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gogate N, Swoveland P, Yamabe T, Verma L, Woyciechowska J, Tarnowska-Dziduszko E, Dymecki J, Dhib-Jalbut S. MHC class I expression on neurons in SSPE and experimental subacute measles encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1986;55:435–443. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopas J, Itzhaky D, Segev Y, Salzberg S, Trink B, Isakov N, Rager-Zisman B. Persistent measles virus infection enhances class I MHC expression and immunogenicity of murine neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1992;34:313–320. doi: 10.1007/BF01741552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin D E, Bellini W J. Measles virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1267–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin D E, Hess J L, Moench T R. Immune responses in the central nervous system. Toxicol Pathol. 1987;15:294–302. doi: 10.1177/019262338701500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffin D E, Mullinix J, Narayan O, Johnson R T. Age dependence of viral expression: comparative pathogenesis of two rodent-adapted strains of measles virus in mice. Infect Immun. 1974;9:690–695. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.4.690-695.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hallensleben W, Schwemmle M, Hausmann J, Stitz L, Volk B, Pagenstecher A, Staeheli P. Borna disease virus-induced neurological disorder in mice: infection of neonates results in immunopathology. J Virol. 1998;72:4379–4386. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4379-4386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herndon R M, Rubinstein L J. Light and electron microscopy observations in the development of viral particles in the inclusions of Dawson’s encephalitis (subacute sclerosing panencephalitis) Neurology. 1967;18:8–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.18.1_part_2.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikegami H, Takeda M, Doi K. An age-related change in susceptibility of rat brain to encephalomyocarditis virus infection. Int J Exp Pathol. 1997;78:101–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1997.d01-245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joly E, Mucke L, Oldstone M B A. Viral persistence in neurons explained by a lack of MHC class I expression. Science. 1991;253:1283–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.1891717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katayama Y, Hotta H, Nishimura A, Tatsuno Y, Homma M. Detection of measles virus nucleoprotein mRNA in autopsied brain tissues. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:3201–3204. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-12-3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz M. Clinical spectrum of measles. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;191:1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78621-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koprowski H, Dietzschold B. Rabies: lessons from the past and a glimpse into the future. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;232:239–257. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovarik J, Siegrist C-A. Immunity in early life. Immunol Today. 1998;19:150–152. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liebert U G, Finke D. Measles virus infections in rodents. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;191:149–166. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78621-1_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebert U G, Flanagan S G, Loffler S, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Rima B K. Antigenic determinants of measles virus hemagglutinin associated with neurovirulence. J Virol. 1994;68:1486–1493. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1486-1493.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipkin W I, Tyler K L, Waksman B H. Viruses, the immune system and central nervous system diseases. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:43–45. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGeer P L, McGeer E G. The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;21:195–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosier D E, Cohen P L. Ontogeny of mouse T-lymphocyte function. Fed Proc. 1975;34:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naniche D, Varior-Krishnan G, Cervoni F, Wild T F, Rossi B, Rabourdin-Combe C, Gerlier D. Human membrane cofactor protein (CD46) acts as a cellular receptor for measles virus. J Virol. 1993;67:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6025-6032.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nash A A, Jayasuriya A, Phelan J, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H, Prospero T. Different roles for L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ T cell subsets in the control of an acute herpes simplex virus infection in skin and nervous system. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:825–833. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-3-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niewiesk S, Brinckmann U, Bankamp B, Sirak S, Liebert U G, ter Meulen V. Susceptibility to measles virus-induced encephalitis in mice correlates with impaired antigen presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1993;67:75–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.75-81.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pachner A R. The immune response to infectious diseases of the central nervous system: a tenuous balance. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1996;18:25–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00792606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rall G F. CNS neurons: the basis and benefits of low class I major histocompatibility complex expression. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;232:115–134. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72045-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rall G F, Manchester M, Daniels L R, Callahan E M, Belman A R, Oldstone M B A. A transgenic mouse model for measles virus infection of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4659–4663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rall G F, Oldstone M B A. Virus-neuron-cytotoxic T lymphocyte interactions. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;202:261–273. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79657-9_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rima B K, Earle J A P, Baczko K, Rota P A, Bellini W J. Measles virus strain variations. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;191:65–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78621-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roos R P, Griffin D E, Johnson R T. Determinants of measles virus (hamster neurotropic strain) replication in mouse brain. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:722–727. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.6.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sidhu M S, Crowley J, Lowenthal A, Karcher D, Menonna J, Cook S, Udem S, Dowling P. Defective measles virus in human subacute sclerosing panencephalitis brain. Virology. 1994;202:631–641. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Streilein J W. Immune privilege as the result of local tissue barriers and immunosuppressive microenvironments. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:428–432. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tardieu M, Powers M L, Weiner H L. Age-dependent susceptibility to reovirus type 3 encephalitis: role of viral and host factors. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:602–607. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tellez-Nagel I, Harter D H. Subacute sclerosing leukoencephalitis: ultrastructure of intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions. Science. 1966;154:899–901. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3751.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner L P, Fleming J O. Viral infections of the nervous system. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:207–224. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.2.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wekerle H, Linington C, Lassman H, Meyermann R. Cellular immune reactivity within the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitley R J, Arvin A. Herpes simplex infections of the central nervous system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;232:258–272. [Google Scholar]