Abstract

Background

High levels of macrolide resistance and increasing fluoroquinolone resistance are making Mycoplasma genitalium increasingly difficult to treat. Minocycline is an alternative treatment for patients with macrolide-resistant M genitalium infections that have failed moxifloxacin, or for those with fluoroquinolone contraindications or resistance. Published efficacy data for minocycline for M genitalium are limited.

Methods

We evaluated minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC). Microbial cure was defined as a negative test of cure within 14–90 days after completing minocycline. The proportion cured and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated, and logistic regression was used to explore factors associated with treatment failure. We pooled data from the current study with a prior adjacent case series of patients with M genitalium who had received minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days at MSHC.

Results

Minocycline cured 60 of 90 (67% [95% CI, 56%–76%]) infections. Adherence was high (96%) and side effects were mild and self-limiting. No demographic or clinical characteristics were associated with minocycline failure in regression analyses. In the pooled analyses of 123 patients, 83 (68% [95% CI, 58%–76%]) were cured following minocycline.

Conclusions

Minocycline cured 68% of macrolide-resistant M genitalium infections. These data provide tighter precision around the efficacy of minocycline for macrolide-resistant M genitalium and show that it is a well-tolerated regimen. With high levels of macrolide resistance, increasing fluoroquinolone resistance, and the high cost of moxifloxacin, access to nonquinolone options such as minocycline is increasingly important for the clinical management of M genitalium.

Keywords: antibacterial agents, minocycline, moxifloxacin, Mycoplasma genitalium, sexually transmitted infections

Minocycline is well tolerated, inexpensive, and widely accessible and has 67% efficacy for the treatment of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium.

Mycoplasma genitalium is a sexually transmissible pathogen and is an established cause of nongonococcal urethritis in men [1, 2] and cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and adverse obstetric outcomes in women [3]. Mycoplasma genitalium is becoming increasingly difficult to treat. Macrolide resistance exceeds 50% in some regions [4] and has been shown to exceed 80% among men who have sex with men (MSM) attending Australia's largest sexual health service, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC) [5]. At MSHC, moxifloxacin is used as first-line treatment for macrolide-resistant M genitalium [6]. If this regimen fails or moxifloxacin is contraindicated, clinicians select from minocycline, pristinamycin, or sitafloxacin, depending on tolerability and contraindications [7–9]. In many settings, access to these options is limited and the cost for some of these drugs is prohibitive. Fluoroquinolone resistance is also on the rise and has reached 25% (ie, for parC S83I) in urban Melbourne, further impacting drug selection and cure [10]. As such, nonfluoroquinolone alternatives are being sought.

Minocycline is an option for patients with macrolide-resistant M genitalium infections that have failed treatment with fluoroquinolones or for those situations in which fluoroquinolones are contraindicated or not locally accessible. It is widely available, inexpensive, and off-patent. Existing data around the efficacy of minocycline for M genitalium are limited to case reports and our previous small series of 35 patients [8]. Our study seeks to provide contemporary estimates around microbial cure, incidence of adverse effects, and adherence to the required 14-day regimen to inform clinician use of this therapeutic option. To provide tighter precision around microbial cure, we pooled our data with a previously reported small case series from our group that immediately preceded this study [8].

METHODS

We undertook a retrospective analysis of all patients who were prescribed 14 days of minocycline for the treatment of M genitalium infection at MSHC between 1 February 2020 and 17 May 2022. Ethics approval was provided by the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number 232/16).

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the analysis if they had M genitalium detected on a urogenital or anal sample prior to commencing treatment, were treated with minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days for the first time for this infection, completed >50% of the prescribed treatment regimen, completed a test of cure 14–90 days after completion of treatment, and were not deemed to be at high risk for reinfection. In keeping with our previous studies, risk of reinfection was classified as high risk if cases reported condomless penetrative vaginal and/or anal intercourse with an untested and/or untreated or partially treated ongoing partner [6, 11, 12]. Only the first M genitalium infection treated with minocycline for each individual during the study period was included in the study, and any subsequent infections were excluded.

It is routine practice at MSHC to be reviewed for an M genitalium test of cure 14–28 days after completing any treatment regimen. At the test of cure consultation, clinicians complete a standardized electronic template that captures information regarding resolution of symptoms, adherence, adverse events, sexual activity during and following treatment, and testing and treatment status of sex partner(s).

During the study period, there was a change in the assay used for the diagnosis of M genitalium at MSHC. From 1 February 2020 to 28 February 2021, all samples were tested for M genitalium and M genitalium macrolide resistance using the ResistancePlus MG assay (SpeeDx Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia), and from 1 March 2021 to 17 May 2022, all samples were tested for M genitalium using the M genitalium transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) assay (Aptima Hologic Gen-Probe Panther System; Hologic, San Diego, California), which is somewhat more sensitive, detecting lower-load infection [13]. Samples that tested positive for M genitalium by TMA were then tested using the ResistancePlus MG assay, so that a macrolide resistance profile was available. MSHC routinely generates a macrolide resistance result for M genitalium infections at the time of diagnosis and uses resistance-guided therapy for the treatment of M genitalium infections [6, 12]. Microbial cure was defined as a negative test of cure within 14–90 days of completing treatment. The proportion with microbial cure and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by exact methods. Logistic regression was used to explore characteristics associated with treatment failure.

To provide greater precision around microbial cure, we then pooled data from the current study with a prior case series of 35 patients with M genitalium infection, who had been treated with minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days using the same inclusion criteria as above. This series immediately preceded the current study (May 2018 to February 2020) and had the same eligibility criteria [8].

RESULTS

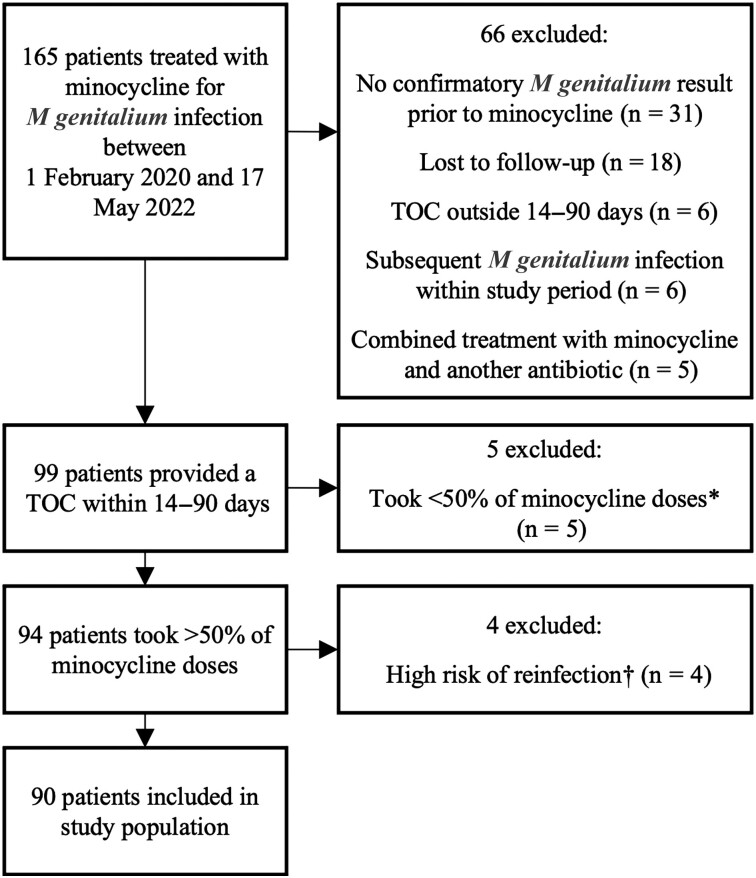

From 1 February 2020 to 17 May 2022, 165 patients with macrolide-resistant M genitalium were treated with minocycline for 14 days. Patients were excluded from the analysis for the following reasons: no confirmatory test for M genitalium undertaken at MSHC prior to receiving minocycline (n = 31), did not return for a test of cure (ie, lost to follow-up, n = 18), did not have a test of cure within the period 14–90 days from treatment completion (n = 6), treatment with minocycline was administered in combination with another antibiotic (n = 5), at high risk of reinfection (n = 4), or took <50% of the 14-day minocycline regimen (n = 5) (Figure 1). In addition, 6 patients received minocycline twice during the study period and their second treatment event was excluded. As a result, 90 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection. *Two patients stopped medication due to side effects (headaches and blurred vision). †Reported condomless penetrative intercourse with an untreated/partially treated ongoing partner. Abbreviation: TOC, test of cure.

Population Characteristics

The study population had a median age of 29 years (range, 19–53 years) (Table 1). Of the 90 patients included in the study, 25 (27%) were women, 34 (38%) were heterosexual men, and 31 (34%) were MSM. All patients had macrolide-resistant M genitalium infections. Two women had multisite infections (cervicovaginal and anal); therefore, the total number of M genitalium infections included in the study was 92. A total of 58 (63%) infections were male urethral (diagnosed with first-pass urine samples), 25 (27%) were cervicovaginal (diagnosed with 21 cervicovaginal swabs and 4 first-pass urine samples), and 9 (10%) were anorectal.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (range) | 29 (19–53) |

| Gender/sexual orientation (n = 90) | |

| Femalea | 25 (27.2) |

| Heterosexual male | 34 (37.8) |

| MSMb | 31 (34.4) |

| Site of infection (n = 92) | |

| Cervicovaginalc | 25 (27.2) |

| Anorectal | 9 (9.8) |

| Urethral (all male FPU) | 58 (63) |

| Indication for minocycline (n = 90) | |

| Persistent Mycoplasma genitalium, failed prior treatment | |

| Asymptomatic | 18 (20) |

| Male urethritis | 36 (40) |

| Rectal symptomsd | 2 (2.2) |

| Female genital/pelvic symptomse | 9 (10) |

| First treatment for M genitalium | |

| Male urethritis | 18 (20) |

| Rectal symptomsf | 2 (2.2) |

| Female genital/pelvic symptomsg | 1 (1.1) |

| Asymptomatic | 4 (4.4) |

| Prior antibiotic treatment (n = 90) | |

| No prior treatmenth | 25 (27.8) |

| Prior treatmenti | 65 (72.2) |

| 1 prior treatment regimen | 35 (38.9) |

| ≥2 prior treatment regimens | 30 (33.3) |

| Adherence | |

| No missed doses documented | 86 (95.6) |

| Missed 1–6 doses | 4 (4.4) |

| Side effects | |

| Dizziness/lightheadedness | 8 (8.9) |

| Nausea | 5 (5.6) |

| Headache | 5 (5.6) |

| Fatigue/lethargy | 4 (4.4) |

| Derealization/“brain fog”/low mood | 4 (4.4) |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (3.3) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (2.2) |

| Reflux/heartburn | 2 (2.2) |

| Otherj | 7 (7.8) |

Abbreviations: FPU, first-pass urine; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Two patients had multisite infections.

Includes 1 man having sex with a transgender woman.

Represents 21 cervicovaginal swabs and 4 FPU samples.

Mild dyschezia (n = 1), discharge (n = 1).

Urinary symptoms (n = 1), abnormal bleeding (n = 3), abnormal bleeding + discharge (n = 1), pelvic pain + abnormal bleeding + altered vaginal discharge (n = 1), pelvic pain (n = 2), altered vaginal discharge (n = 1).

Itch (n = 1), mild discomfort (n = 1).

Pelvic pain (n = 1).

Sixteen of 25 patients had received doxycycline prior to commencing minocycline (median, 7 days). Fourteen were symptomatic and 2 were contacts of infection.

Six of 65 patients had received doxycycline prior to commencing minocycline (median, 7 days). Sixty-four of these patients had previously received and failed treatment with moxifloxacin. Additional antibiotics that patients had been exposed to included azithromycin (n = 25), sitafloxacin (n = 12), pristinamycin (n = 9), and lefamulin (n = 2).

Includes rash, bloating, sleep disturbance, dry eyes, and sun sensitivity.

For 25 (28%) patients, minocycline was their first treatment for macrolide-resistant M genitalium. The most common reasons that minocycline was used for first-line treatment were drug–drug interactions with moxifloxacin, previous adverse reactions to quinolones, or other medical contraindications. Of these, 18 (20%) were men who presented with urethritis, 4 patients were asymptomatic contacts, 2 men presented with mild rectal symptoms, and 1 woman presented with pelvic pain. The remaining 65 (72%) patients were treated with minocycline for a persistent M genitalium infection that had failed other antimicrobials: 36 (40%) men presented with urethritis, 18 (20%) men were asymptomatic, 2 men had rectal symptoms, and 9 (10%) were women with genital/pelvic symptoms. Of these 9 women, 3 presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding, 2 with pelvic pain, 1 with altered vaginal discharge, 1 with urinary symptoms, 1 with abnormal vaginal discharge and bleeding, and 1 with pelvic pain, abnormal bleeding, and vaginal discharge.

Of the 65 (72%) patients who had failed a prior antibiotic regimen(s), 35 (39%) had received 1 prior regimen, and 30 (33%) patients had received ≥2 prior regimens. A total of 62 (69%) patients had failed a moxifloxacin-containing regimen. Other prior regimens received contained sitafloxacin, azithromycin, pristinamycin, and lefamulin.

Microbial Cure

Of the 90 patients included in the study population, 60 (66.7% [95% CI, 53.3%–78.3%]) experienced microbial cure within 14–90 days of completing minocycline. We next examined the impact of epidemiological, clinical, and behavioral factors on microbial cure by logistic regression analysis (Table 2). While small numbers limited our ability to determine impact of gender/sexual orientation on cure, the odds of failing minocycline were similar in all 3 subgroups (P > .7): 17 of 25 females (68% [95% CI, 46.5%–85.1%]) experienced microbial cure, along with 22 of 34 heterosexual males (64.7% [95% CI, 46.5%–80.3%]) and 21 of 31 MSM (67.7% [95% CI, 48.6%–83.3%]). When examining microbial cure by anatomical site, 17 of 25 cervicovaginal infections (68.0% [95% CI, 46.5%–85.1%]), 7 of 9 rectal infections (77.8% [95% CI, 40.0%–97.2%]), and 38 of 58 male urethral infections (65.6% [95% CI, 51.9%–77.5%]) were cured. There was no significant difference in odds of minocycline failure between these 3 sites (P > .5). There was also no significant difference in the odds of failure between individuals with and without symptoms (63.6% [95% CI, 40.7%–82.8%] and 67.6% [95% CI, 55.2%–78.5%], respectively; odds ratio [OR], 0.84 [95% CI, .31–2.29]; P = .729). Of the 25 patients who had not received any prior treatment for M genitalium, 18 experienced microbial cure (72% [95% CI, 50.1%–87.9%]) compared to 42 of the 65 previously treated patients (64.6 [95% CI, 51.8%–76.1%]). There was no statistical difference in the odds of failure between these 2 groups (OR, 1.41 [95% CI, .51–3.87]; P = .507). Last, of the 86 patients who did not report any missed doses of minocycline, 59 experienced microbial cure (68.6% [95% CI, 57.7%–78.2%]), whereas only 1 of the 4 patients who reported missing 1–6 doses of minocycline experienced microbial cure (25% [95% CI, .6%–80.1%]); there was no significant difference in the odds of failure between these 2 groups (OR, 6.55 [95% CI, .65–65.95]; P = .121), but small numbers again affected this comparison.

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Failure (N = 90)

| Factor | Cured | Failed | OR (95% CI) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (% [95% CI]) | No. (% [95% CI]) | |||

| Total patients | 60 (66.7 [53.3–78.3]) | 30 (33.3 [17.3–52.8]) | … | |

| Gender/sexual orientation | ||||

| Female | 17 (28.3 [17.5–41.4]) | 8 (26.7 [12.3–45.9]) | Ref | |

| Heterosexual male | 22 (36.7 [24.6–50.1]) | 12 (40 [22.7–59.4]) | 1.16 (.39–3.47) | .792 |

| MSMb | 21 (35 [23.1–48.4]) | 10 (33.3 [17.3–52.8]) | 1.01 (.33–3.13) | .984 |

| Site of infectionc | ||||

| Cervicovaginal | 17 (27.4 [16.9–40.2]) | 8 (26.7 [12.3–45.9]) | Ref | |

| Anorectal | 7 (11.3 [4.7–21.9]) | 2 (6.7 [.8–22.1]) | 0.71 (.11–4.47) | .719 |

| Urethral (male FPU) | 38 (61.3 [48.1–73.4]) | 20 (66.7 [47.2–82.7]) | 1.38 (.47–4.05) | .563 |

| Presence of symptoms | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 14 (23.3 [13.4–36.0]) | 8 (26.7 [12.3–45.9]) | Ref | |

| Symptomatic | 46 (76.7 [64.0–86.6]) | 22 (73.3 [54.1–87.7]) | 0.84 (.31–2.29) | .729 |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| No prior treatment | 18 (30 [18.8–43.2]) | 7 (23.3 [9.9–42.3]) | Ref | |

| Any prior treatment | 42 (70 [56.8–81.2]) | 23 (76.7 [57.7–90.1]) | 1.41 (.51–3.87) | .507 |

| Adherence | ||||

| No reported missed doses | 59 (98.3 [91.1–100]) | 27 (90 [73.5–97.9]) | Ref | |

| Missed 1–6 doses | 1 (1.7 [.4–8.9]) | 3 (10 [2.1–26.5]) | 6.55 (.65–65.95) | .121 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FPU, first-pass urine; MSM, men who have sex with men; OR, odds ratio.

P values calculated using logistic regression. For site of infection, the analysis was clustered by participant.

Includes 1 man having sex with a transgender woman.

For site of infection, the sample size is 92.

Adherence to Treatment and Adverse Effects

Adherence and adverse effects were reported in the final study population where >50% adherence to minocycline was required. Among the final study population, 86 patients (96%) reported taking all minocycline doses. Side effects were mostly mild and self-limiting and predominantly affected the gastrointestinal or central nervous systems. A total of 8 patients reported dizziness, 5 patients reported nausea, 5 reported headache, 4 reported fatigue/lethargy, and 4 reported a feeling of derealization, “brain fog,” or low mood (Table 1). Interestingly, of the 165 prescriptions of minocycline provided by MSHC between 1 February 2020 and 17 May 2022 before assessment for eligibility for this study (Figure 1), only 5 (3%) people reported <50% adherence and were excluded from this study, and 2 of these 5 patients had stopped the medication prematurely due to side effects (reported headache and/or blurred vision, which resolved).

Pooled Data

With the aim of increasing accuracy around efficacy estimates for 14 days of minocycline, we pooled data with our prior case series of 35 patients who had been treated with the same regimen at MSHC in the period that immediately preceded this study (ie, May 2018–February 2020) [8]. Of the 35 patients in that series, 33 fulfilled the eligibility criteria for the current study, creating a pooled dataset of 123 patients with macrolide-resistant M genitalium who were treated with minocycline (Table 3). Of the 123 patients, overall cure was 67.5% (95% CI, 58.4%–75.6%). We undertook logistic regression analyses in this larger dataset to determine if any factors were associated with microbial failure, but no statistically significant associations between patient characteristics and treatment failure were found (P > .169).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Failure When Pooled With a Prior Population

| Factor | Pooled Data (n = 123) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cured | Failed | OR (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

| No. (% [95% CI]) | No. (% [95% CI]) | |||

| Total patients | 83 (67.5 [58.4–75.6]) | 40 (32.5 [24.4–41.6]) | … | |

| Gender/sexual orientation | ||||

| Female | 27 (32.5 [22.6–43.7]) | 11 (27.5 [14.6–43.9]) | Ref | |

| Heterosexual male | 30 (36.1 [25.9–47.4]) | 17 (42.5 [27–59.1]) | 1.39 (.55–3.49) | .482 |

| MSMb | 26 (31.3 [21.6–42.4]) | 12 (30 [16.6–46.5]) | 1.13 (.43–3.02) | .803 |

| Site of infectionc | ||||

| Cervicovaginal | 27 (31.8 [22.1–42.8]) | 11 (27.5 [14.6–43.9]) | Ref | |

| Anorectal | 7 (8.2 [3.3–16.2]) | 2 (5.0 [.6–16.9]) | 0.70 (.13–3.85) | .683 |

| Urethral (male FPU) | 51 (60 [48.8–70.5]) | 27 (67.5 [50.9–81.4]) | 1.30 (.56–3.03) | .544 |

| Presence of symptoms | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 17 (20.5 [12.4–30.8]) | 9 (22.5 [10.8–38.5]) | Ref | |

| Symptomatic | 66 (79.5 [69.2–87.6]) | 31 (77.5 [61.5–89.2]) | 0.89 (.36–2.21) | .797 |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| No prior treatment | 22 (26.5 [17.4–37.3]) | 8 (20 [9.1–35.6]) | Ref | |

| Any prior treatment | 61 (73.5 [62.7–82.6]) | 32 (80 [64.4–90.9]) | 1.35 (.54–3.40) | .517 |

| Adherence | ||||

| No reported missed doses | 80 (96.4 [89.8–99.2]) | 36 (90 [76.3–97.2]) | Ref | |

| Missed 1–6 doses | 3 (3.6 [.8–10.2]) | 4 (10 [2.8–23.7]) | 2.96 (.63–13.93) | .169 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FPU, first-pass urine; MSM, men who have sex with men; OR, odds ratio.

P values calculated using logistic regression. For site of infection, the analysis was clustered by participant.

Includes 1 man having sex with a transgender woman.

For site of infection, the sample size is 125 for the pooled population.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective real-world analysis of the effectiveness of minocycline found that 66.7% (95% CI, 53.3%–78.3%) of macrolide-resistant M genitalium infections were cured with a 14-day regimen of minocycline. While this case series of 90 patients is the largest reported to date, our findings are consistent with the previous published series of 35 patients, which reported that 71% (95% CI, 54%–85%) were cured following minocycline [8]. This finding of 67% cure following minocycline is slightly lower than the cure reported following pristinamycin (75% [95% CI, 66%–82%]) [8, 9] and, importantly, slightly higher than cure following moxifloxacin (59% [95% CI, 46.7%–69.9%]) in the presence of S83I parC mutations [10].

In the era of rising macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance, clinicians increasingly need to access alternatives to fluoroquinolones. Having more confidence and precision around cure for minocycline enables clinicians to discuss treatment options with patients who have persistent M genitalium infections or drug contraindications, as well as in settings with limited drug options and/or high prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance.

Minocycline is a second-generation, semi-synthetic tetracycline analogue that has been on the market since the late 1960s [14, 15], and there is a long history of data on minocycline safety and tolerability [14, 15]. Minocycline is generally well tolerated. Common side effects tend to be neurological (eg, weakness, dizziness, headache) and gastrointestinal (eg, abdominal cramps) [16]. Product labeling states the incidence of common side effects as 9% for dizziness, 9% for fatigue, 5% for pruritus, and 4% for malaise [17]. There is a known risk of idiopathic intracranial hypertension with tetracyclines, which presents as headache, tinnitus, and transient visual obscurations; however, this is a rare adverse effect. A systematic review of available literature from 1900 through 2019 identified 32 cases of idiopathic intracranial hypertension associated with minocycline use, almost all of which were associated with long-term use for acne treatment [18]. Patients in our analysis reported mostly mild and self-limiting adverse effects and we found that the incidence of reported adverse effects in the study population was similar to available published data outlined above. Reassuringly, of the 165 prescriptions of minocycline provided by MSHC between February 2020 and May 2022, only 2 patients stopped their medication prematurely due to side effects (headaches and blurred vision, which resolved completely and were not deemed to be idiopathic intracranial hypertension).

A considerable advantage of minocycline compared to moxifloxacin, sitafloxacin, and pristinamycin is that it is widely accessible at low cost. A course of minocycline comes at a direct cost of AU$9 (US$6.4) to pharmacies in Australia. In contrast, antibiotics such as moxifloxacin and pristinamycin cost up to AU$87 (US$61) and AU$207 (US$146), respectively. In addition to this, the majority of these alternative regimens are not readily available in community pharmacies. Furthermore, pristinamycin and sitafloxacin both require an application to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, the equivalent of the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration and the United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, limiting access to these drugs to specialized services. In other countries, alternative regimens may not be accessible at all; for example, at the time of writing, pristinamycin is not available in the US and sitafloxacin is not available in the US or Europe. Based on these reasons, minocycline offers genuine opportunities for clinicians in high-, low-, and middle-income countries to treat macrolide-resistant M genitalium.

In contrast to macrolides and quinolones, the mechanisms of tetracycline failure in the treatment of M genitalium are not well understood. Based on in vitro data, tetracyclines appeared highly promising for the treatment of M genitalium, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) indicating that many isolates of M genitalium should be doxycycline susceptible [19, 20]. The MICs of minocycline for reference and clinical strains were slightly lower than those of doxycycline [21], indicating it may be more effective, although structural differences between the 2 antibiotics also likely impact the efficacy of each drug in vivo [21]. While there are no large clinical studies using minocycline for the treatment of M genitalium, randomized trials largely conducted over a decade ago consistently found that the tetracycline doxycycline was inferior to azithromycin in eradicating M genitalium with proportion cured in the order of 20%–40% [4]. However, no molecular mechanisms of resistance in the 16S ribosomal RNA gene have been found to consistently explain the low efficacy of doxycycline [22], and no correlation between MICs and microbial cure has been demonstrated [20].

Importantly, our analysis did not find any statistically significant associations with minocycline failure, although our sample size is likely to have impacted on these comparisons. It is interesting to note that of the 9 anorectal infections, 7 (77.8%) were cured compared to the 17 of 25 (68.0%) cervicovaginal infections (OR, 0.71 [95% CI, .11–4.47]; P = .719). It would be important to establish if there is indeed a difference in efficacy by anatomical site with a larger sample size. It has been shown that minocycline is more lipophilic than tetracycline and demonstrates greater tissue penetration, including into the intestinal epithelium [14, 23, 24], which could support a potential increased efficacy for anorectal infections.

In addition to sample size, this study has other limitations. This was a retrospective analysis that relied upon patients’ self-reported recall of information regarding adherence, sexual activity, and adverse effects of treatment. There is also the possibility of attrition bias, as 18 of the initial population of 165 patients (10.9%) were lost to follow-up. This could result in an overreporting of failures, as those with persistent symptoms might be more likely to attend follow-up, although based on our prior studies this cohort had a very high rate of return for test of cure. As participants comprised of sexually transmitted infection clinic attendees, these findings may not be generalizable to the community.

In conclusion, our study provides clinicians with increased precision and confidence around microbial cure (68%) for minocycline for macrolide-resistant infection and shows that it is a well-tolerated regimen associated with predominantly mild side effects in a minority of patients. In the context of rising quinolone resistance, which has reached 25% (ie, for parC S83I) in urban Melbourne [10], the availability of nonquinolone agents such as minocycline is becoming increasingly important. In some regions, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, we may have already reached a point where the efficacy of minocycline is equal to or superior to moxifloxacin [25, 26]. For low- and middle-income countries, the availability of an inexpensive generic that will cure in the order of 2 of 3 macrolide-resistant infections may be welcomed by clinicians and patients.

Contributor Information

Emily J Clarke, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia.

Lenka A Vodstrcil, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia; Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Erica L Plummer, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia; Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Ivette Aguirre, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia.

Ranjit S Samra, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia; Department of Infectious Diseases, Alfred Hospital, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Christopher K Fairley, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia; Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Eric P F Chow, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia; Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Catriona S Bradshaw, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Alfred Health, Carlton, Victoria, Australia; Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We sincerely thank the staff at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre for collecting the clinical data used in analyses, as well as Michelle Doyle, who conducted the earlier series with which we pooled data. E. J. C. is a fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and an advanced trainee with the Australasia Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine.

Patient consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the Alfred Health ethics committee (approval number 232/16). Written patient consent was not required as this was a retrospective audit.

Financial support. C. K. F. and C. S. B. are supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Leadership Investigator Grants (grant numbers GNT1172900 and GNT1173361, respectively), and E. P. F. C. is supported by an NHMRC Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (grant number 1172873).

References

- 1. Horner PJ, Gilroy CB, Thomas BJ, Naidoo RO, Taylor-Robinson D. Association of Mycoplasma genitalium with acute non-gonococcal urethritis. Lancet 1993; 342:582–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradshaw CS, Tabrizi SN, Read TRH, et al. Etiologies of nongonococcal urethritis: bacteria, viruses, and the association with orogenital exposure. J Infect Dis 2006; 193:336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lis R, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and female reproductive tract disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manhart LE, Gillespie CW, Lowens MS, et al. Standard treatment regimens for nongonococcal urethritis have similar but declining cure rates: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:934–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Read TRH, Murray GL, Danielewski JA, et al. Symptoms, sites, and significance of Mycoplasma genitalium in men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25:719–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Durukan D, Read TRH, Murray G, et al. Resistance-guided antimicrobial therapy using doxycycline-moxifloxacin and doxycycline-2.5 g azithromycin for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infection: efficacy and tolerability. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Durukan D, Doyle M, Murray G, et al. Doxycycline and sitafloxacin combination therapy for treating highly resistant Mycoplasma genitalium. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26:1870–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doyle M, Vodstrcil LA, Plummer EL, Aguirre I, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS. Nonquinolone options for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium in the era of increased resistance. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:ofaa291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Read TRH, Jensen JS, Fairley CK, et al. Use of pristinamycin for macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2018; 24:328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murray GL, Bodiyabadu K, Vodstrcil LA, et al. parC variants in Mycoplasma genitalium: trends over time and association with moxifloxacin failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022; 66:e0027822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vodstrcil LA, Plummer EL, Doyle M, et al. Combination therapy for Mycoplasma genitalium, and new insights into the utility of parC mutant detection to improve cure. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Read TRH, Fairley CK, Murray GL, et al. Outcomes of resistance-guided sequential treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infections: a prospective evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:554–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salado-Rasmussen K, Tolstrup J, Sedeh FB, Larsen HK, Unemo M, Jensen JS. Clinical importance of superior sensitivity of the Aptima TMA-based assays for Mycoplasma genitalium detection. J Clin Microbiol 2022; 60:e0236921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jonas M, Cunha BA. Minocycline. Ther Drug Monit 1982; 4:137–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garrido-Mesa N, Zarzuelo A, Gálvez J. Minocycline: far beyond an antibiotic. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 169:337–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. AMH Pty Ltd . Australian medicines handbook 2020. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd;2020.

- 17. US Food and Drug Administration . Solodyn (minocycline HCl).2011. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/050808s014lbl.pdf. Accessed December 2022.

- 18. Tan MG, Worley B, Kim WB, Ten Hove M, Beecker J. Drug-induced intracranial hypertension: a systematic review and critical assessment of drug-induced causes. Am J Clin Dermatol 2020; 21:163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jensen JS, Nørgaard C, Scangarella-Oman N, Unemo M. In vitro activity of the first-in-class triazaacenaphthylene gepotidacin alone and in combination with doxycycline against drug-resistant and -susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020; 9:1388–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wood GE, Jensen NL, Astete S, et al. Azithromycin and doxycycline resistance profiles of U.S. Mycoplasma genitalium strains and their association with treatment outcomes. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59:e0081921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hamasuna R, Jensen JS, Osada Y. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Mycoplasma genitalium strains examined by broth dilution and quantitative PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:4938–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chua TP, Danielewski J, Bodiyabadu K, et al. Impact of 16S rRNA single nucleotide polymorphisms on Mycoplasma genitalium organism load with doxycycline treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022; 66:e0024322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhanel GG, Homenuik K, Nichol K, et al. The glycylcyclines: a comparative review with the tetracyclines. Drugs 2004; 64:63–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aronson AL. Pharmacotherapeutics of the newer tetracyclines. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1980; 176(10 Spec No):1061–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ando N, Mizushima D, Takano M, et al. High prevalence of circulating dual-class resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in asymptomatic MSM in Tokyo. Japan. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2021; 3:dlab091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamasuna R, Le PT, Kutsuna S, et al. Mutations in ParC and GyrA of moxifloxacin-resistant and susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0198355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]