Abstract

Background

Secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure during pregnancy increases the risk of infant stillbirth, congenital malformations, low birth weight and respiratory illnesses. However, little is known about the extent of SHS exposure during pregnancy. We assessed the prevalence of SHS exposure in pregnant women in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

We used Demographic and Health Survey data collected between 2008 and 2013 from 30 LMICs. We estimated weighted country-specific prevalence of SHS exposure among 37 427 pregnant women. We accounted for sampling weights, clustering and stratification in the sampling methods. We also explored associations between sociodemographic variables and SHS exposure in pregnant women using pairwise multinomial regression model.

Findings

The prevalence of daily SHS exposure during pregnancy ranged from 6% (95% CI 5% to 7%) (Nigeria) to 73% (95% CI 62% to 81%) (Armenia) and was greater than active tobacco use in pregnancy across all countries studied. Being wealthier, maternal employment, higher education and urban households were associated with lower SHS exposure in full regression models. SHS exposure in pregnant women closely mirrors WHO Global Adult Tobacco Survey male active smoking patterns. Daily SHS exposure accounted for a greater population attributable fraction of stillbirths than active smoking, ranging from 1% of stillbirths (Nigeria) to 14% (Indonesia).

Interpretation

We have demonstrated that SHS exposure during pregnancy is far more common than active smoking in LMICs, accounting for more stillbirths than active smoking. Protecting pregnant women from SHS exposure should be a key strategy to improve maternal and child health.

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy is an important and avoidable risk to fetal development and contributes to adverse perinatal and postnatal outcomes, often with a lasting and negative impact during infancy and beyond.1 The prevalence of active smoking during pregnancy and its associated risks are well documented in existing literature.2 However, the evidence on the effect of secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure during pregnancy is still growing.3 Published research suggests that exposure to SHS can increase the risk of stillbirth (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.38), congenital malformation (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.26),4 and low birthweight infants (risk ratio (RR) 1.16; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.36).5 Tobacco control is recognised as an important contributor to overall health and as a contributor to non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention through the inclusion of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) as one of the means of implementation to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3, ‘Good Health and Wellbeing’.6 This issue highlights that tobacco control impacts more than just NCDs, including the more traditional development goals such as maternal and child health, poverty reduction and reduced inequalities.

Global prevalence estimates for active smoking during pregnancy have been published7 but there are no existing global estimates of the prevalence of SHS exposure in pregnancy in the literature. Based on the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in 51 low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), the pooled prevalence of any tobacco use in pregnant women was found to be 2.6% (95% CI 1.8 to 3.6).7 Conversely, only one report exists of an international survey of SHS exposure in pregnant women, conducted in nine LMICs, suggesting that the prevalence of SHS exposure could range between 17.1% in Democratic Republic of Congo and 91.6% in Pakistan.8 While data already exist on SHS exposure among women of reproductive age,9 10 evidence suggests that smoking behaviours can change during pregnancy; including asking smokers to refrain from smoking indoors where a pregnant women may reside.11–14 SHS exposure among women of reproductive age is therefore a reasonable proxy but is not the same as exposure during pregnancy.

There are several reasons to believe that for many LMICs, SHS exposure could pose a larger attributable risk to pregnancy and birth outcomes than active smoking. First, some of the risks of antenatal outcomes associated with SHS exposure are comparable with the risks associated with other modifiable factors; for example, the risk of stillbirth with active smoking (OR 1.4) and with a body mass index of greater than 30 kg/m2 (OR 1.6) are comparable with the risk associated with passive smoking (OR 1.23).4 Second, evidence suggests that more than a third of non-smoking women (35%) in their reproductive age could be exposed to SHS in LMICs.15 This indicates the potential for SHS exposure in pregnancy. Consequently, the attributable risk and population attributable fraction (PAF) due to passive smoking could be compared with active smoking in pregnancy.7 However, before reaching this conclusion, better global estimates of the prevalence of SHS exposure in pregnancy are required.

Our paper addresses this particular gap in knowledge. We estimated the prevalence of SHS exposure in households with pregnant women in 30 LMICs. Recently, DHS included a question on the frequency of smoking inside households in phase 6 of their questionnaire. This provided an opportunity to estimate SHS prevalence in pregnancy and compare it with active smoking rates.16 17 We also explored variables associated with SHS exposure in pregnant women and a PAF for passive smoking for stillbirths in selected countries.

METHODS

Data source

We conducted a secondary analysis of the most recent (phase 6) DHS data collected between 2008 and 2013 from all LMICs using DHS standard household questionnaires. DHS are nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys that collect information on populations and their health. The DHS Program is a United States Agency for International Development funded project and is implemented by ICF International. Surveys are conducted at 5-year intervals across LMICs, using model questionnaires designed to collect comparable data.18

National samples are selected based on a stratified two-stage cluster design. Enumeration areas are determined, and a representative sample of households is selected from each enumeration area. Eligible members of each selected household are then interviewed as appropriate using household, woman’s and man’s questionnaires as required. It is assumed that the nationally representative samples of women are also nationally representative of pregnant women.

The household questionnaire is used to collect information on characteristics of the household’s dwelling unit and characteristics of usual residents and visitors. It is also used to identify members of the household who are eligible for an individual interview. Eligible respondents are then interviewed using a woman’s or a man’s questionnaire. Eligibility for interview includes adults between the ages of 15 and 49 years who slept in the household the night before the survey. All eligible participants from each household are included in the data collection process for DHS Program. Data are anonymised at the point of collection, and interviews are only conducted if the participant provides informed consent.

Study indicators

The primary outcome of this study was to determine the prevalence of exposure to household SHS in pregnancy. Pregnancy status is self-reported and established from question 226 from the Women’s Model Questionnaire ‘Are you pregnant now?’ with the option of a yes or no answer. Prevalence and frequency of household SHS exposure were determined using question 101 of the DHS Household Standard Questionnaire, ‘How often does anyone smoke inside your house? Would you say daily, weekly, monthly, less than monthly, or never?’ Active smoking status was self-reported and determined from question 1004, ‘Do you currently smoke cigarettes?’ with the option of a yes or no answer and question 1007, ‘What (other) types of tobacco do you currently smoke or use?’ (pipe, chewing tobacco, cigar, snuff, other country-specific). For this analysis, active smoking was limited to smoked tobacco products (cigarettes, pipes, cigars and country-specific smoked tobaccos). Active smokers Were excluded from SHS calculations. Age, urban residence, wealth index, occupational status and educational status were also extracted from the dataset for all pregnant women for each country. This provided a comparison between pregnant women who were exposed to household SHS versus those who were not exposed and those who smoked firsthand.

For the purpose of this analysis, relevant variables (table 1) from the Women’s Model and the Household Standard Questionnaires were merged together. Countries with an insufficient response rate (<80%) to question 101 were excluded from the analysis to avoid imputations for the missing data. Comparison of prevalence estimates between complete case and imputed datasets are described. The 30 individual country databases were then merged into a single database for analysis.

Table 1.

Variables included for analysis and their definition taken from the DHS Household and Women's Model Questionnaires

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Household Questionnaire | |

| Number of household members | Discrete count of total individuals living in the household. |

| Total adults measured | Discrete count of total adults living in the household. |

| Type of place of residence | Type of place of residence where the household resides as either urban or rural. |

| Wealth index | The wealth index is a composite measure of a household's cumulative living standard. The wealth index is calculated by DHS using household's ownership of selected assets, such as televisions and bicycles; materials used for housing construction; and types of water access and sanitation facilities. Generated with a statistical procedure known as principal components analysis, the wealth index places individual households on a continuous scale of relative wealth. DHS separates all interviewed households into five wealth quintiles to compare the influence of wealth on various population, health and nutrition indicators (1 being the poorest group and 5 the richest). |

| Number of rooms used for sleeping | Discrete count of total number of rooms used for sleeping in the household. |

| Land used for agriculture | Own land usable for agriculture. |

| Place food cooked | Food cooked in the house, in separate building, or outdoors. |

| Household has a separate room used as a kitchen | Whether household has a separate room that is used as a kitchen. |

| Food cooked on stove or open fire | Food cooked on stove or open fire. |

| Household has a chimney, hood or neither | Presence of a chimney, hood or neither in the household. |

| Type of cooking fuel | Type of cooking fuel presented as unordered categorical data: electricity, LPG, natural gas, biogas, kerosene, coal, lignite. |

| Household smoking | Frequency household members smoke inside the house: daily, weekly, monthly, less than monthly, never. |

| Women’s Model Questionnaire | |

| Maternal age | Current age in completed years is calculated from the century month code of the date of birth of the respondent (MV011) and the century month code of the date of interview (MV008). |

| Pregnancy status | Whether the respondent is currently pregnant: yes, no. |

| Marital status | Current marital status of the respondent presented as unordered categorical data: never in union, married, living with partner, widowed, divorced, no longer living together/separated. |

| Maternal occupation | Standardised respondent’s occupation groups presented as unordered categorical data: not working, professional/ technical/managerial, clerical, sales, agricultural employee, household and domestic, skilled manual, unskilled manual, don’t know. |

| Highest educational level | Highest education level attained. This is a standardised variable providing level of education in the following ordered categories: no education, primary, secondary, higher. |

| Maternal tobacco use | Whether respondent currently classifies herself as a smoker of tobacco: yes, no. |

DHS, Demographic Health Surveys; LPG, liquefied petroleum gas.

Statistical analyses

Analysis was conducted using StataSE V.14 software. The samples for DHS surveys were designed to permit data analysis of regional subsets within the sample population and therefore required the use of sample weights during analysis to ensure samples were representative. StataSE SVY and SVYSET commands were used to account for sampling weights, clustering and stratification in the sampling design. Continuous measures were reported as means with 95% CIs, and categorical data were reported as counts and percentages. Response rates were summarised descriptively with the data.

We used a pairwise multinomial regression model to assess variation in the risk of household SHS exposure among the sociodemographic variables of interest. Bivariate coefficients were calculated for each explanatory variable of interest (urban vs rural dwelling, education level obtained, working vs not working and wealth quintile) and the outcome variable (frequency of exposure to household SHS). We collapsed frequency of exposure outcome into three categories: daily, some (which included ‘weekly’, ‘monthly’ and ‘less than monthly’) and never. We included each of these variables in the full model, as none were collinear and all except urban dwelling had significant bivariate associations. Urban dwelling was kept in the full model, as it is an important cofactor with the other covariates.

We then calculated predictive margins from the pairwise regression to obtain the probabilities of each level of household SHS exposure (daily, some, never) for each value of each covariate, given all of the covariates included in the model.19

We calculated the PAF of stillbirths due to active smoking and due to daily household SHS exposure for 30 LMICs. We used respective estimates of the OR of stillbirth due to active smoking (OR1.36)20 and SHS (OR 1.23)4 from meta-analyses and the prevalence of each found in this study, using the formula for PAF21:

We used OR in place of relative risk, as stillbirth is a low-frequency outcome and available meta-analyses present OR. Collected prevalence data for active smoking in pregnancy were used to provide a comparison with household SHS exposure.

RESULTS

Thirty-six countries in the DHS database completed the phase 6 of the questionnaire. Thirty countries were included in our analysis: 19 from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA); 3 each from Southeast Asia (SEA), Europe (EURO) and the Eastern Mediterranean (MENA); and 2 from Latin America/Caribbean (LAC).22 These countries had 100% response rate to question 101 of the DHS Household Standard Questionnaire. Six countries (Cameroon, Dominican Republic, Malawi, Niger, Philippines and Senegal) did not include question 101 in their DHS Household Standard Questionnaire and therefore did not collect data for this question (0% response rate) and were excluded from the analysis. The demographics of pregnant women according to smoking status by country studied can be found in online supplementary file 1.

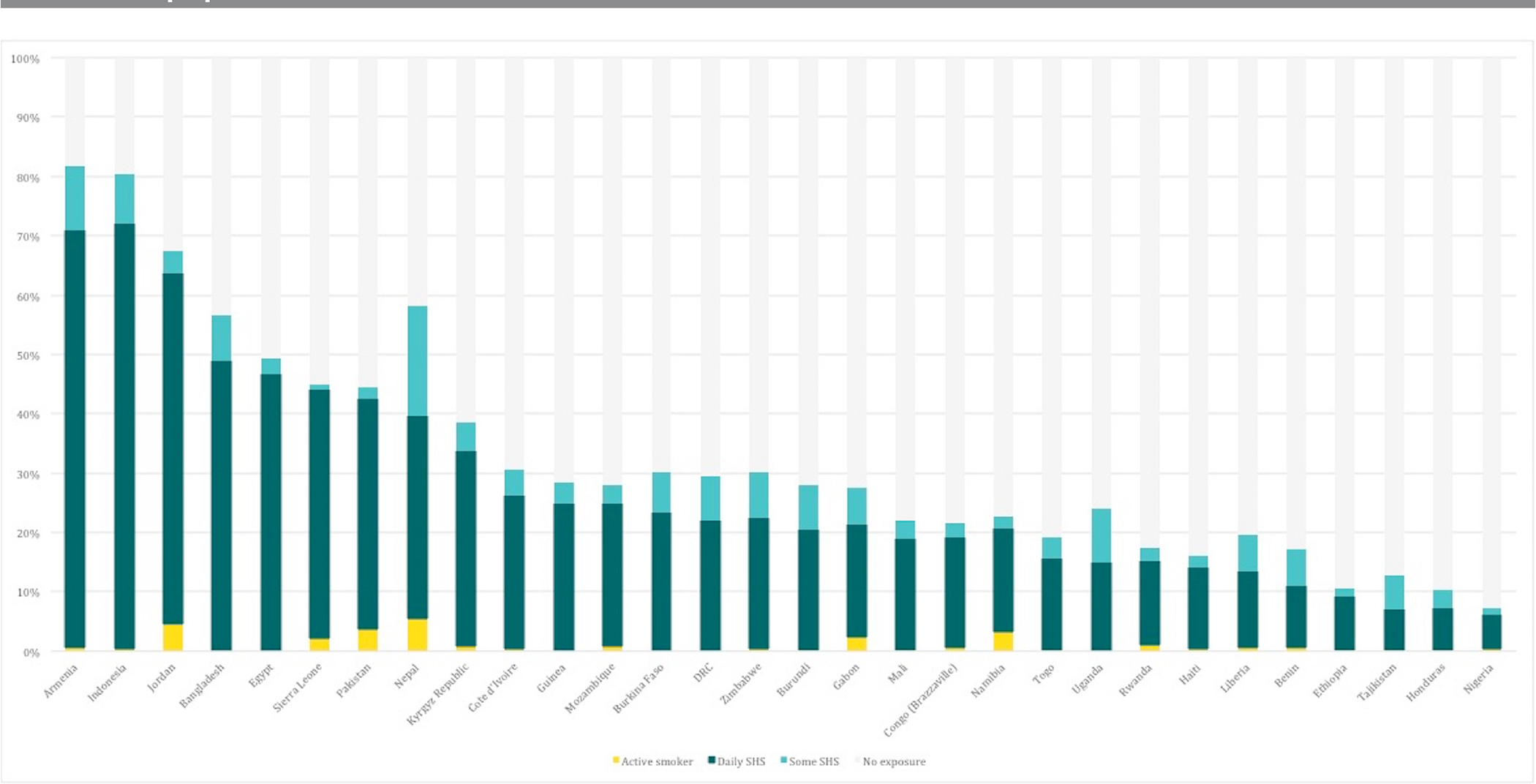

Any exposure to household SHS ranged from 7% (6% to 9%) of pregnant women (Nigeria) to 81% (72% to 88%) (Armenia) of pregnant women (figure 1). In all 30 countries studied, daily was the most common frequency of exposure reported which ranged from 6% (5% to 7%) of pregnant women (Nigeria) to 73% (62% to 81%) (Armenia) (figure 1). In five countries, Jordan, Armenia, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Nepal, more than 50% of pregnant women were exposed at any frequency, and in three countries, Jordan, Armenia and Indonesia, more than 50% of pregnant women reported daily SHS exposure. In all countries studied, the prevalence of SHS exposure during pregnancy is substantially greater than the prevalence of active smoking in pregnancy. Cumulative regional estimates of daily SHS exposure were highest in countries studied in SEA (57% (55% to 60%) of pregnant women), and lowest in countries studied in LAC (10% (8% to 11%) of pregnant women) (table 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of active smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) in pregnancy.

Table 2.

Regional household SHS exposure prevalence

| Pregnant women (n) | Active smoker (95% CI) | Daily sHs (95% CI) | some shs (95% CI) | Never exposed (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| EURO | 1462 | 0.39% (0.16% to 0.98%) | 24.78% (21.57% to 28.3%) | 5.59% (4.38% to 7.11%) | 69.24% (65.6% to 72.65%) |

| LAC | 2148 | 0.84% (0.46% to 1.54%) | 9.64% (8.14% to 11.37%) | 4.67% (3.76% to 5.79%) | 84.85% (82.92% to 86.6%) |

| MENA | 5421 | 2.21% (1.63% to 3.01%) | 47.08% (45.17% to 49.00%) | 2.71% (2.09% to 3.50%) | 48% (46.03% to 49.97%) |

| SEA | 3188 | 1.33% (0.96% to 1.84%) | 57.23% (54.87% to 59.55%) | 11.36% (9.92% to 12.98%) | 30.08% (27.94% to 32.32%) |

| SSA | 25 208 | 0.53% (0.42% to 0.66%) | 17.97% (17.27% to 18.69%) | 4.01% (3.67% to 4.39%) | 77.49% (76.69% to 78.27%) |

| Total | 37 427 | 0.80% (0.69% to 0.94%) | 24.65% (23.97% to 25.33%) | 4.61% (4.31% to 4.93%) | 69.94% (69.19% to 70.68%) |

EURO, Europe; LAC, Latin America and Caribbean; MENA, Middle East and North Africa; SEA, South East Asia; SHS, secondhand smoke; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa.

The mean age of SHS-exposed pregnant women ranged from 22.5 (Nepal) to 27.9 (Ethiopia), while the mean age of active smoking pregnant women ranged from 23.7 (Liberia) to 35 (Tajikistan) (see online supplementary file 1). The percentage of SHS-exposed pregnant women with no education ranged from 0% (Armenia, Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan) to 85% (79% to 90%) (Benin) (see online supplementary file 1). The percentage of pregnant women with no education increased from non-smokers to SHS-exposed to active smokers as a consistent trend in 25 of 30 countries (except for Gabon, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria and Togo). The percentage of pregnant women with no employment ranged from 10% (6% to 17%) in Burundi to 92% (90% to 94%) in Egypt, with no consistent trend between smoking and working status across the countries. The percentage of pregnant women in the lowest wealth quintile exposed to SHS ranged from 13% (5% to 27%) (Tajikistan) to 35% (29% to 42%) (Mozambique). The percentage of women in the lowest wealth quintile increased from non-smoking to SHS-exposed to active smoking in 20 of 30 countries. Lastly, the percentage of SHS-exposed pregnant women in urban areas ranged from 6% (4% to 10%) (Burundi) to 82% (78% to 85%) (Jordan). In 16 of 30 countries, the percentage of pregnant women in urban areas decreased from non-smoking to SHS-exposed to active smoking.

Regression results

Given the covariates in the model, the highest probabilities for daily household SHS exposure in pregnant women was for women in the SEA countries studied (0.60, 0.58 to 0.62) and in the MENA countries studied (0.50, 0.48 to 0.52), and the lowest probability was for women in LAC countries studied (table 3). The probability of daily household SHS exposure decreased with increasing wealth, from 0.31 (0.30 to 0.32) in the poorest wealth quintile to 0.17 (0.16 to 0.19) in the wealthiest quintile. Within educational attainment, a primary school education was associated with the highest probability for daily household SHS exposure, followed by no education (0.26, 0.25 to 0.27) and then secondary and higher. A higher probability for daily exposure was observed for pregnant women in households in urban areas (0.28, 0.27 to 0.29) than for women in rural households (0.23, 0.23 to 0.24). No difference in exposure was observed between pregnant women who had an occupation and women who did not work, given all covariates.

Table 3.

Pairwise multinomial logistic regression according to employment, educational attainment, wealth quintile, location and region with 95% CIs

| Household sHs exposure |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women (n) | Daily (95% CI) | some (95% CI) | Never (95% CI) | ||

|

| |||||

| Employment | Working | 23 449 | 0.25 (0.24 to 0.25) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.71) |

| Not working | 17 516 | 0.25 (0.24 to 0.26) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.71) | |

| Educational attainment | No education | 14 490 | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.27) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.71) |

| Primary | 11 709 | 0.27 (0.26 to 0.28) | 0.05 (0.05 to 0.06) | 0.68 (0.67 to 0.69) | |

| Secondary | 12 016 | 0.24 (0.23 to 0.25) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 0.71 (0.70 to 0.72) | |

| Higher | 2748 | 0.20 (0.18 to 0.22) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 0.75 (0.73 to 0.77) | |

| Wealth quintile | Poorest | 9825 | 0.31 (0.30 to 0.32) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.66) |

| Poorer | 8895 | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.27) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) | |

| Middle | 8077 | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.27) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) | |

| Richer | 7527 | 0.22 (0.21 to 0.23) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.74) | |

| Richest | 6641 | 0.17 (0.16 to 0.19) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.78 (0.77 to 0.80) | |

| Location | Urban | 13 393 | 0.28 (0.27 to 0.29) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.68 (0.67 to 0.69) |

| Rural | 27 572 | 0.23 (0.23 to 0.24) | 0.05 (0.05 to 0.05) | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.72) | |

| Region | SSA | 28 745 | 0.18 (0.17 to 0.18) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.04) | 0.78 (0.78 to 0.79) |

| SEA | 3753 | 0.60 (0.58 to 0.62) | 0.11 (0.09 to 0.12) | 0.30 (0.28 to 0.32) | |

| MENA | 4857 | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.52) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.50) | |

| LAC | 2148 | 0.09 (0.08 to 0.11) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) | |

| EURO | 1462 | 0.28 (0.25 to 0.31) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.07) | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.70) | |

EURO, Europe; LAC, Latin America and Caribbean; MENA, Middle East and North Africa; SEA, South East Asia; SHS, secondhand smoke; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa.

Population attributable fraction

The PAF of stillbirths ranged from 0.01 in Nigeria to 0.14 in Armenia (table 4). In each of the 30 countries, the PAF of stillbirths due to household SHS exposure was comparable with the PAF of stillbirths due to active smoking. This highlights that addressing both active smoking and household SHS exposure during pregnancy should be of priority for healthcare professionals and policy-makers.

Table 4.

Population-attributable fractions for stillbirth due to active smoked tobacco use and daily household SHS exposure

| Country | Rounded PAF Daily household sHs exposure | Rounded PAF Active smoking |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Indonesia | 0.14 (0.06, 0.2) | 0.002 (0.002, 0.002) |

| Armenia | 0.13 (0.06, 0.19) | 0.001 (0.001,0.001) |

| Jordan | 0.11 (0.05, 0.16) | 0.012 (0.01,0.014) |

| Bangladesh | 0.09 (0.04, 0.13) | Not available |

| Egypt | 0.09 (0.04, 0.13) | Not available |

| Sierra Leone | 0.08 (0.03, 0.12) | 0.006 (0.005, 0.007) |

| Pakistan | 0.07 (0.03, 0.1 1) | 0.01 (0.008, 0.012) |

| Nepal | 0.06 (0.03, 0.09) | 0.014 (0.012, 0.017) |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 0.06 (0.03, 0.09) | 0.002 (0.002, 0.002) |

| Cote d'Ivoire | 0.05 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.001 (0.001,0.002) |

| Guinea | 0.05 (0.02, 0.07) | Not available |

| Mozambique | 0.05 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.002 (0.002, 0.002) |

| Burkina Faso | 0.04 (0.02,0.06) | No data |

| Zimbabwe | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | No data |

| Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | 0.04 (0.02,0.06) | 0.001 (0.001,0.001) |

| Burundi | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 0.001 (0, 0.001) |

| Gabon | 0.04 (0.02, 0.05) | 0.006 (0.005, 0.007) |

| Mali | 0.04 (0.02, 0.05) | 0.0002 (0.0002, 0.0003) |

| Congo (Brazzaville) | 0.03 (0.02,0.05) | 0.001 (0.001,0.002) |

| Namibia | 0.03 (0.01,0.05) | 0.009 (0.007, 0.01) |

| Togo | 0.03 (0.01,0.04) | 0.0002 (0.0001,0.0002) |

| Uganda | 0.03 (0.01,0.04) | 0.001 (0.001,0.001) |

| Haiti | 0.03 (0.01,0.04) | 0.003 (0.002, 0.003) |

| Rwanda | 0.03 (0.01,0.04) | 0.001 (0.001,0.001) |

| Ethiopia | 0.03 (0.01,0.04) | 0.001 (0.001,0.002) |

| Honduras | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 0.002 (0.002, 0.002) |

| Liberia | 0.02 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.0003 (0.0003, 0.0004) |

| Tajikistan | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.0003 (0.0002, 0.0003) |

| Benin | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.0004 (0.0003, 0.0005) |

| Nigeria | 0.01 (0, 0.02) | 0.001 (0.001,0.001) |

SHS, secondhand smoke; PAF, population attributable factor.

DISCUSSION

In many LMICs, prenatal exposure to tobacco smoke appears more common than previously thought when household SHS exposure is taken into account. In 5 of 30 countries (Armenia, Indonesia, Jordan, Bangladesh and Nepal), more than 50% of pregnant women reported exposure to household SHS. Furthermore, most exposure was reported at a daily frequency, rather than at lower frequency. Regional patterns of household SHS exposure were strong: EURO, MENA and SEA countries showed much higher prevalence of exposure than SSA countries. In 13 countries (Guinea, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Burundi, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Rwanda, Indonesia, Namibia, Jordan, Kyrgyz Republic, Egypt), household SHS exposure was greater than 10 times more prevalent than active smoking. In Egypt, household SHS exposure was 156 times more prevalent than active smoking. In only 5 out of 30 countries (Congo Brazzaville, Gabon, Benin, Mali and Zimbabwe), household SHS exposure was twice as common as active smoking.

The regression model brought out important attributes of household SHS exposure: we observed that pregnant women who worked in any capacity (manual, clerical or other) did not have a different probability for exposure than women who did not work. This suggests that employed women had similar circumstances at home as those who did not work with regard to household SHS exposure. We also found that the probability for household SHS exposure varied by educational attainment, but non-linearly; pregnant women with up to a primary school education had the highest probability for exposure, even compared with pregnant women with no education. Probability for household SHS exposure decreased with increasing wealth, with pregnant women in the lowest wealth quintile at nearly double the probability for SHS exposure than women in the highest wealth quintile. This is consistent with findings that tobacco use and exposure is generally higher in lower income populations, even within LMICs.23 Lastly, household SHS exposure varied by location, both by region and within countries. Pregnant women in urban areas had a higher probability for household SHS exposure than pregnant women in rural areas, and pregnant women in the SEA countries studied had the highest probability of exposure, while pregnant women in the SSA countries studied had the lowest probability of being exposed.

The PAF of stillbirths due to daily household SHS exposure was comparable with the PAF for active smoking during pregnancy. The PAF for other birth complications likely resembles this trend, highlighting that addressing both active smoking and household SHS exposure during pregnancy are important health priorities for healthcare professionals and policy-makers.

While mothers and children in LMICs are exposed to household SHS, many are also regularly exposed to smoke from solid fuel use in the household from activities such as cooking or heating. Solid fuel contains a large number of harmful pollutants (including carbon monoxide, benzene and 1,3-butadiene) and is associated with adverse health and birth outcomes.24 25 The PAF for stillbirth due to exposure to biomass cooking fuel-related household air pollution has been calculated between 0.05 and 0.18.24 25 This is comparable with the burden posed by exposure to SHS with the PAF of stillbirths due to SHS exposure ranging from 0.01 in Nigeria to 0.14 in Armenia and Indonesia.

Previous multinational analyses using DHS data have found low prevalence of active smoking by pregnant women. While Caleyachetty et al7 similarly found highest prevalence in SEA and lowest prevalence in SSA, the study found low prevalence of active smoking in the same Eastern European countries (Armenia, Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan) while our study found high prevalence of daily household SHS exposure among pregnant women in these countries. This suggests active and passive smoking patterns may follow similar trends in some regions, but may diverge in others, underscoring the importance of studying both active and passive smoking.

While this is the first multinational study to assess household SHS exposure in pregnant women, previous studies have assessed household SHS exposure in single countries. Fischer et al found prevalence of daily household SHS exposure among pregnant women in Bangladesh to be 46.7% using the 2011 Bangladesh DHS.26 Our finding of 48.9% (45.26% to 52.55%) from the 2014 Bangladesh DHS suggests prevalence of household SHS exposure has remained constant. This is similarly reflected in previous studies conducted in Jordan that have reported 50.4% of pregnant women are exposed to SHS in the home,27compared with the higher prevalence of 63.4% reported in this study. Fischer et al also found low educational attainment and low wealth to be associated with increased daily SHS exposure.26

Rates of exposure to household SHS in pregnancy compared with active smoking are consistently higher across all countries in our analysis. Smoking has traditionally been viewed as culturally inappropriate for women in many LMICs which has been beneficial as a protector against smoking uptake. However, male smoking prevalence remains high in many LMICs. It is highly likely that the higher rates of household SHS exposure reflected in the analysis are reflecting male smoking behaviours, the rates for which28–33 are similar to our SHS exposure findings.

Household SHS exposure during pregnancy poses a particular challenge for LMICs. Awareness of the harms associated with SHS is often lower in LMICs,34 and in some LMICs, due to patriarchal family structures, women may not feel comfortable challenging male smoking behaviour, even if they are aware of potential harm.34 Furthermore, weak tobacco control policies or implementation result in fewer protections against household SHS exposure and persistence of protobacco social norms. In such environments, with fewer controls on tobacco industry marketing, there is also a potential for future increases in women tobacco users.

LIMITATIONS

While DHS data provide nationally representative estimates, the surveys are self-reported and subject to underestimation. Previous research has found pregnant women may under-report tobacco use, especially women with limited educational attainment and women exposed to SHS. This would lead to a higher prevalence of active and passive smoking than found in this analysis.

The distribution of countries across regions is another limitation of this study, as each region was not represented by an equal number of countries. Except for SSA (19 countries), all regions were represented by two or three countries, based on countries that are included in the DHS study and had completed phase 6 of the survey. Additionally, in calculating the PAF, we were limited to relying on relative risk estimates from pooled meta-analyses that found only four studies that met inclusion criteria. Country-specific relative risks were not available for most countries and highlight a need for future research. Analyses were therefore made on best estimates available from the meta-analyses available in the current literature. However, application of these relative risk estimates may have generated results that may not be representative of these countries.

Furthermore, as this study relies on a secondary analysis of existing DHS data, there are some determinants of exposure that we have not been able to explore, as these were not explored in the existing DHS questionnaires. It was not possible to determine the timing of SHS exposure during pregnancy and therefore how exposure correlates with fetal development. It was also not possible to determine the proximity of the pregnant women to the smoker, the volume of the room or the room’s ventilation system which are all important modifiers of the degree of exposure.35 In addition, residual nicotine can persist in the environment after visible smoke has cleared on interior surfaces, including furniture and clothes.36

Research, policy and practice implications

The interplay of various cultural, economic and political factors creates a challenging environment to address household SHS exposure. Strong, effectively implemented smoke-free policies have been shown to reduce household SHS exposure in workplaces and public spaces.37 38 We explored the relationship between household SHS exposure and the available data on smoke-free legislation and party or signature status to the FCTC by country (see online supplementary file 2). Where data were available there did not appear to be any meaningful and consistent correlation between prevalence of household SHS exposure and either smoke-free legislation or party or signature status to the FCTC. This might suggest that legislation changes are either not comprehensive or not effectively implemented to influence societal norms and thereby reducing SHS exposure at home. However, it is important to note the importance of the inclusion of policies to promote smoke-free environments in multiunit housing and in vehicles which may limit SHS exposure in certain populations outside of the household environment. Ongoing monitoring of tobacco smoking and exposure during pregnancy is important, in addition to tracking tobacco industry efforts to market cigarettes to women. However, this suggests that further efforts may be needed to explore the relationship between household SHS and smoke-free legislation and whether more can be done to reduce household SHS exposure through effective implementation of smoke-free legislation.

Existing international guidelines for the prevention and management of tobacco use and SHS exposure during pregnancy provide recommendations for screening and intervention.39 Healthcare professionals working with pregnant women in antenatal settings should be aware of these issues and should be proactive in raising issues where support can be provided in relation to household SHS exposure during pregnancy. Further research is needed to develop and evaluate novel interventions to reduce household SHS exposure and its related adverse health outcomes for pregnant women.40

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Three primary research articles are published describing the prevalence of secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure in pregnancy in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) that focus on 11 countries in total.

These papers demonstrate that in the countries studied, maternal exposure to SHS is common, from 17.1% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 91.6% in Pakistan. This represents an emerging problem for LMICs in tackling maternal and child health.

Only one research article from Bangladesh provided prevalence data on country-level nationally representative samples.

While national prevalence estimates are available for active smoking during pregnancy for many LMICs, such data are not available to describe the prevalence of SHS exposure during pregnancy.

This is the first study which provides national estimates for 30 LMICs on SHS exposure in pregnancy and shows that these estimates are much higher than active smoking during pregnancy.

For these countries, the estimated population attributable risk due to SHS exposure during pregnancy could be higher than that due to active smoking.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the UK Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

Disclaimer Data collected by the Demographic Health Surveys is anonymised at the point of collection and interviews are only conducted if the participant provides informed consent. This study did not apply for ethics review given its utilisation of secondary anonymous data.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement

Approval has been granted for the use of this data from Demographic Health Surveys for the purposes of this study. Additional unpublished data from this study are available upon request from Demographic Health Surveys.

© Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rogers JM. Tobacco and pregnancy: overview of exposures and effects. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2008;84:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cnattingius S The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004;6:125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonardi-Bee J, Smyth A, Britton J, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and fetal health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2008;93:F351–F361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonardi-Bee J, Britton J, Venn A. Secondhand smoke and adverse fetal outcomes in nonsmoking pregnant women: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011;127:734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salmasi G, Grady R, Jones J, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:423–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations. Sustainable development goals. 2017. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed Sep 2017).

- 7.Caleyachetty R, Tait CA, Kengne AP, et al. Tobacco use in pregnant women: analysis of data from Demographic and Health Surveys from 54 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e513–e520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloch M, Althabe F, Onyamboko M, et al. Tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy: an investigative survey of women in 9 developing nations. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1833–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberg M, Woodward A, Jaakkola MS, et al. Global estimate of the burden of disease from second-hand smoke. 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44426/1/9789241564076_eng.pdf (accessed 12 Jan 2018).

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure among women of reproductive age–14 countries, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:877–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyssälä L, Rautava P, Sillanpää M, et al. Changes in the smoking and drinking habits of future fathers from the onset of their wives’ pregnancies. J Adv Nurs 1992;17:849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollak KI, Mullen PD. An exploration of the effects of partner smoking, type of social support, and stress on postpartum smoking in married women who stopped smoking during pregnancy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 1997;11:182–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett KD, Gage J, Bullock L, et al. A pilot study of smoking and associated behaviors of low-income expectant fathers. Nicotine Tob Res 2005;7:269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gage JD, Everett KD, Bullock L. A review of research literature addressing male partners and smoking during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2007;36:574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, et al. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 2011;377:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The DHS Program. DHS-Questionnaires. http://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/DHS-Questionnaires.cfm (accessed Mar 2016).

- 17.The DHS Program. DHS Model Questionnaire – Phase 6 (2008–2013) (French, English). http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-dhsq6-dhs-questionnaires-and-manuals.cfm (accessed Mar 2016).

- 18.The DHS Program. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). http://www.dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/DHS.cfm (accessed Jan 2016).

- 19.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics 1999;55:652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;377:1331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flegal KM, Panagiotou OA, Graubard BI. Estimating population attributable fractions to quantify the health burden of obesity. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:201–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. WHO regional offices. 2017. http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/ (accessed Aug 2017).

- 23.World Health Organisation. Tobacco and poverty: a vicious circle. Geneva 2004. http://www.who.int/tobacco/communications/events/wntd/2004/en/wntd2004_brochure_en.pdf (accessed Aug 27, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sehgal M, Rizwan SA, Krishnan A. Disease burden due to biomass cooking-fuel-related household air pollution among women in India. Glob Health Action 2014;7:25326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakshmi PV, Virdi NK, Sharma A, et al. Household air pollution and stillbirths in India: analysis of the DLHS-II National Survey. Environ Res 2013;121:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer F, Minnwegen M, Kaneider U, et al. Prevalence and determinants of secondhand smoke exposure among women in Bangladesh, 2011. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azab M, Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH, et al. Exposure of pregnant women to waterpipe and cigarette smoke. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:231–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). 2015. http://gatsatlas.org/#section_read (accessed Aug 2017).

- 29.World Health Organization. Tobacco control country profiles. 2017. http://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/policy/country_profile/en/ (accessed Jan 2018).

- 30.World Health Organization. Guinea tobacco country profile. 2002. http://www.who.int/tobacco/media/en/Guinea.pdf (accessed Jan 2018).

- 31.World Health Organization. Jordan tobacco country profile. 1999. http://www.who.int/tobacco/media/en/Jordan.pdf (accessed Jan 2018).

- 32.World Health Organization. Tobacco control fact sheet: Tajikistan. 2016. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/337435/Tobacco-Control-Fact-Sheet-Tajikistan.pdf (accessed Jan 2018).

- 33.Index Mundi. Mali - smoking prevalence. 2018. https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/mali/smoking-prevalence (accessed Jan 2018).

- 34.Passey ME, Longman JM, Robinson J, et al. Smoke-free homes: what are the barriers, motivators and enablers? A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintana PJ, Matt GE, Chatfield D, et al. Wipe sampling for nicotine as a marker of thirdhand tobacco smoke contamination on surfaces in homes, cars, and hotels. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaleta D, Polanska K, Usidame B. Smoke-free workplaces are associated with protection from second-hand smoke at homes in nigeria: evidence for population-level decisions. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierce JP, White VM, Emery SL. What public health strategies are needed to reduce smoking initiation? Tob Control 2012;21:258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and management of tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in pregnancy. 2013. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/pregnancy/guidelinestobaccosmokeexposure/en/ (accessed Aug 2017). [PubMed]

- 40.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Rolle IV, et al. Clinical interventions to reduce secondhand smoke exposure among pregnant women: a systematic review. Tob Control 2015;24:217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Approval has been granted for the use of this data from Demographic Health Surveys for the purposes of this study. Additional unpublished data from this study are available upon request from Demographic Health Surveys.

© Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted.