Abstract

Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease remains a challenge, and the development and validation of novel cognitive markers of Alzheimer’s disease is critical to earlier disease detection. The goal of the present study is to examine brain-behavior relationships of translational cognitive paradigms dependent on the medial temporal lobes and prefrontal cortices, regions that are first to undergo Alzheimer’s-associated changes. We employed multi-modal structural and functional MRI to examine brain-behavior relationships in a healthy, middle-aged sample (N=133; 40–60 years). Participants completed two medial temporal lobe-dependent tasks (virtual Morris Water Task and Transverse Patterning Discriminations Task), and a prefrontal cortex-dependent task (Reversal Learning Task). No associations were found between various MRI measures of brain integrity and the Transverse Patterning or Reversal Learning tasks (p’s>.05). We report associations between virtual Morris Water Task performance and medial temporal lobe volume, hippocampal microstructural organization, fornix integrity, and functional connectivity within the executive control and frontoparietal control resting state networks (all p’s<0.05; did not survive correction for multiple comparisons). This study suggests that virtual Morris Water Task performance is associated with medial temporal lobe integrity in middle age, a critical window for detection and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease, and may be useful as an early cognitive marker of Alzheimer’s disease risk.

Keywords: middle age, virtual Morris Water Task, transverse patterning, reversal learning, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Despite considerable advances in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers to facilitate preclinical detection (Jack et al., 2016), early detection of AD-associated cognitive dysfunction remains a challenge. Conventional neuropsychological measures of memory and executive functioning, the primary cognitive domains affected by AD, have high sensitivity and specificity to detect mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and predict conversion from MCI to dementia (Bondi et al., 2014). However, they are less useful in distinguishing healthy aging from subtle cognitive changes in preclinical AD (Greenwood, Lambert, Sunderland, & Parasuraman, 2005). Translational paradigms tightly tied to the neural circuits known to be affected in AD may reveal subtle cognitive dysfunction, serving as inexpensive and non-invasive markers of risk for AD-associated cognitive decline.

AD preferentially targets the medial temporal lobe (MTL) and prefrontal cortex, including MTL atrophy (Barnes et al., 2009), altered hippocampal biochemistry (Dixon, Bradley, Budge, Styles, & Smith, 2002; Parnetti et al., 1996), disrupted white matter integrity of corticolimbic tracts (Acosta-Cabronero & Nestor, 2014; Amlien & Fjell, 2014), and aberrant fronto-temporal functional connectivity (Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2006; Zarei et al., 2013). Thus, we would predict that MTL- and prefrontal cortex-dependent cognitive functions would be among the first to be disrupted by AD. Lesion studies in non-human animals have identified discrete processes that depend on the MTL and prefrontal cortex (Kesner & Churchwell, 2011; Olsen, Moses, Riggs, & Ryan, 2012; Strange, Witter, Lein, & Moser, 2014). Here, we focus our investigation on three paradigms translated from animal models that have been proposed as potential AD markers: 1) the virtual Morris Water Task (vMWT), a spatial MTL-dependent task; 2) the Transverse Patterning Discriminations Task (TPDT), a non-spatial MTL-dependent task; and 3) the Reversal Learning Task (RLT), a task dependent on the prefrontal cortex. Each task has been extensively studied in rodent models and validated in healthy young adults (Astur, Ortiz, & Sutherland, 1998; Cornwell, Johnson, Holroyd, Carver, & Grillon, 2008; Fellows & Farah, 2003), cognitively normal older adults (Antonova et al., 2009; Driscoll et al., 2003; Driscoll, Hamilton, Yeo, Brooks, & Sutherland, 2005; Ostreicher, Moses, Rosenbaum, & Ryan, 2010), and patients with MCI and dementia (Laczó et al., 2010; Laczó et al., 2009). However, existing studies have largely neglected middle-aged individuals, who may be vulnerable to and already accumulating AD pathology. Understanding brain-behavior associations within this middle-aged group is critically important to guide early detection and intervention efforts.

The purpose of this study was to use multi-modal MR imaging to examine the neural underpinnings of translational cognitive paradigms in cognitively normal middle-aged adults. Specifically, we hypothesized that vMWT and TPDT performance would be associated with structural and functional measures of MTL integrity, while RLT performance would be associated with measures of prefrontal cortical integrity. We have previously reported that the ApoE ε4 allele, the largest known genetic risk factor for AD, is not associated with poorer performance on the vMWT, TPDT, or RLT in middle-aged adults (Korthauer, Awe, Frahmand, & Driscoll, 2018). However, we hypothesized that ApoE genotype would moderate associations between brain integrity and cognitive performance, with ε4 carriers showing stronger brain-behavior relationships given their greater vulnerability to early AD neuropathology. By focusing on healthy middle-aged adults, this study represents an important step in validating novel paradigms as potential cognitive markers of AD-associated cognitive impairment.

Method

Study Design

133 community-dwelling, White, right-handed adults aged 40 to 60 years (M=50.0 years, SD=6.2; 50 men; M=15.2 years education, SD=2.3) underwent cognitive testing and MR imaging. Exclusion criteria included a history of central nervous system disease (e.g., dementia, Parkinson’s disease, stroke), severe cardiac disease, metastatic cancer, serious mental illness, substance use disorder, or contraindication to MRI. Participants were screened for cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975; one participant excluded due to score <25) and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS-2; Mattis, 1988; four participants excluded due to score < 135).

Cognitive Measures

Computerized cognitive tasks were administered on a Dell computer with a 17-inch monitor. The vMWT, TPDT, and RLT have been described in detail elsewhere (Korthauer et al., 2018); brief descriptions appear below.

Virtual Morris Water Task (vMWT)

The vMWT featured a circular pool of opaque water in a square room with four distal cues. Participants completed five blocks of four learning trials. They began in a random location in the pool and were instructed to find the hidden platform as quickly as possible. Latency, path length, and heading error were calculated for each trial and summed across learning trials to create summary measures of performance. After the learning trials, participants completed a 60-second probe trial in which the hidden platform was removed without their knowledge. The proportion of latency and distance spent in the goal quadrant were measures of memory for the platform location.

Transverse Patterning Discriminations Test (TPDT)

The TPDT consisted of six stepwise phases. Two non-nameable black stimuli were presented on a white background. Participants pressed a left or right response key to indicate one stimulus of the pair. Visual and auditory feedback indicated correct versus incorrect trials. Participants were not informed of the response contingencies but were told to try to get as many correct as possible. Phases 1–3 were elemental discriminations (Phase 1: A+B-, Phase 2: A+B-, C+D−; Phase 3: A+B-, C+D−, E+F-). Phases 4–6 were transverse patterning discriminations (Phase 4: G+H-; Phase 5: G+H-, H+I-; Phase 6: G+H-, H+I-, I+G-). Each phase continued until participants reached 11 correct out of 12 trials (maximum 400 trials across all phases). Dependent variables included total number of trials and total errors for phases 4–6.

Reversal Learning Task (RLT)

The RLT consisted of six stepwise phases. Phases 1–3 were elemental discriminations (A+B-, C+D−, E+F-). Phases 4–6 were reversed contingencies (Phase 4: A-B+; Phase 5: A-B+, C-D+; Phase 6: A-B+, C-D+, E-F+). Dependent variables included total number of trials and total errors for phases 4–6.

Multi-Modal MRI

Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired on a GE Signa 3T scanner (Waukesha, WI) with a quad-split quadrature transmit/receive head coil. The multi-modal imaging paradigm included: 1) T1-weighted imaging (‘spoiled grass’ [SPGR] sequence with axial acquisition, TR=35 ms, TE=5 ms, flip angle=45°, matrix=256×256, field of view=24 cm, Nex=1); 2) diffusion tensor imaging (spin echo single shot, echo-planar imaging sequence with sensitivity [SENSE=2.5] encoding, 2.2 mm isotropic voxels, 212×212 mm FOV, 96×96 acquired matrix, TR/TE=6338/69 ms, 60 slices for whole brain coverage, with diffusion gradients applied along 32 non-collinear directions at a b-factor of 700 s/mm2, including one minimally weighted image with b=0 s/mm2); 3) 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (spectra acquired from two 2×2×2 cm voxels placed in the posterior left and right hippocampus, respectively, with PRESS TR=2000 ms, TE=35 ms, 1024 points, 200 Hz spectral width, 256 averages, and 16 averages of unsuppressed water spectra with the same parameters); and 4) eyes-closed resting state fMRI (an 8-minute T2*-weighted functional scan obtained with echo-planar pulse imaging, 28 axial slices, 20×20 cm2 FOV, 64×64 matrix, 3.125 mmx3.125 mmx4 mm voxels, TE=40 ms, TR=2,000 ms).

Data Processing

Regional Brain Volumes.

Freesurfer cortical parcellation and subcortical segmentation (Dale, Fischl, & Sereno, 1999; Fischl et al., 2002; Fischl et al., 2004) was performed to define 80 ROIs (Freesurfer v6.0). All cortical and subcortical surface representations were manually inspected and edited by a trained rater to ensure accurate volumetric estimates. Volumes of the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal cortex were summed to create a summary measure of the right and left medial temporal lobe volume. A summary measure of prefrontal cortical volume was created by summing volumes of the bilateral lateral and medial orbitofrontal cortex, rostral and caudal anterior cingulate cortex, rostral and caudal middle frontal cortex, superior frontal cortex, and frontal poles. Regional volumes were normalized by dividing by total intracranial volume.

Hippocampal Microstructural Organization.

DTI B0 images were skull-stripped using FSL’s BET (Smith, 2002); the resulting mask was applied to diffusion-weighted images. The “eddy” tool (Andersson & Sotiropoulos, 2016) was used to correct eddy current-induced distortions and subject movement. DTIFIT (Behrens, Berg, Jbabdi, Rushworth, & Woolrich, 2007) was used to fit a diffusion tensor model at each voxel. Hippocampal masks (from Freesurfer segmentation, described above) were used to extract FA and MD as measures of hippocampal microstructural organization.

Hippocampal Biochemistry.

Water suppressed single voxel spectra were analyzed LCModel (Provencher, 2001), a fully automated, standard curve fitting software. The area under the peak was normalized to the unsuppressed water peak. Metabolite concentrations of N-acetyl aspartate (neuron-axonal compound), Glx (glutamine + glutamate), mI (myo-inositol, predominantly present in glial cells), and Cr (creatine, a measure of cellular energy currency) were calculated. Metabolite concentrations were estimated with Cramer Rao lower bounds lower than 20% of the calculated concentrations. Values were expressed as ratios with creatine.

Microstructural Organization of Hippocampal-Associated White Matter Tracts.

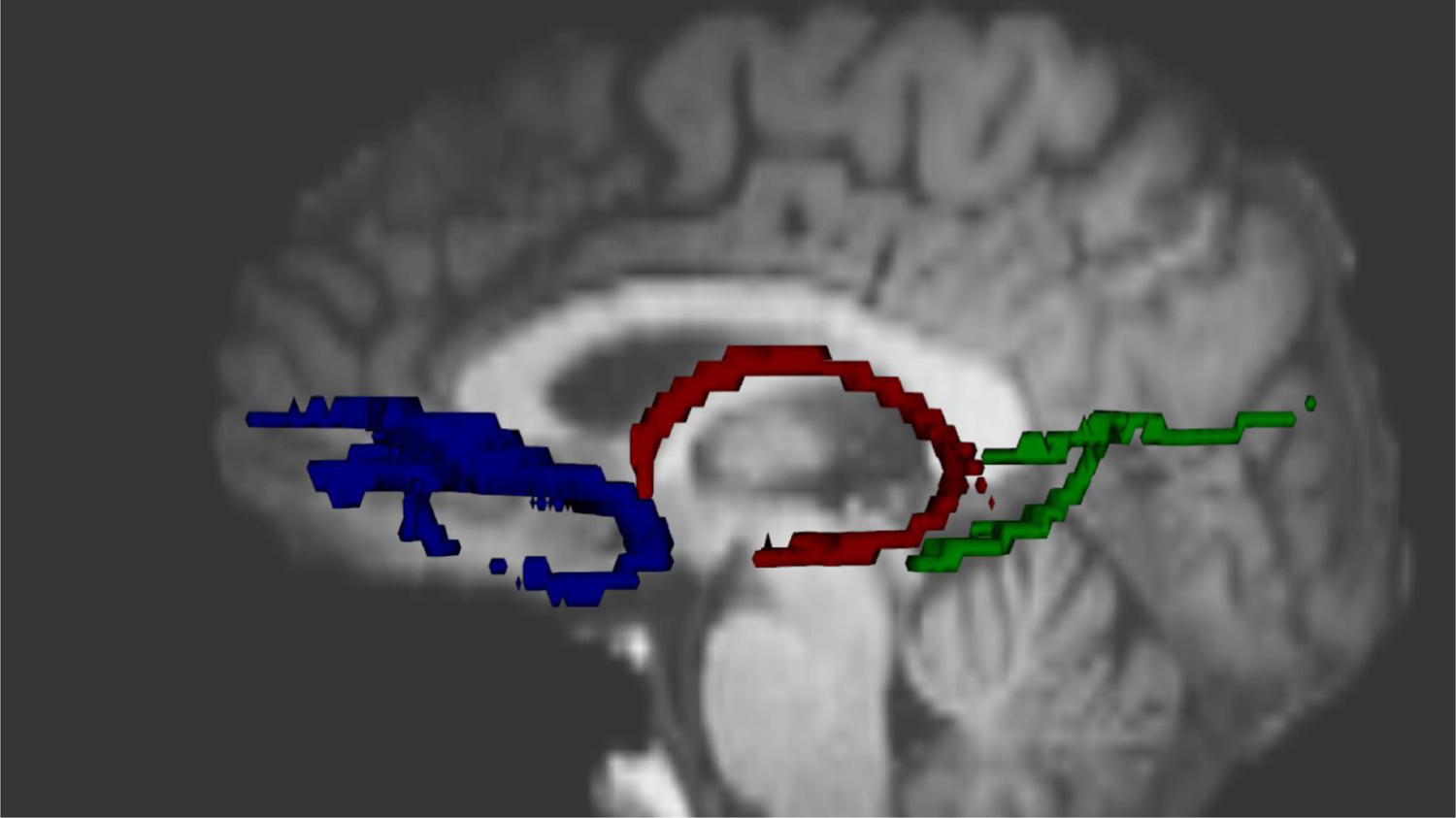

A probability distribution of fiber direction was generated at each voxel of the eddy current-corrected DTI images using BEDPOSTX (Behrens et al., 2003). Probabilistic tractography was used to derive three MTL-associated white matter tracts (uncinate fasciculus, posterior/parahippocampal cingulum bundle, and fornix; see Figure 1) using previously published methods (Kiuchi et al., 2009; Metzler-Baddeley, Baddeley, Jones, Aggleton, & O’Sullivan, 2013). The resulting tracts were normalized by dividing by the proportion of total streamlines sent from the respective seed regions and thresholded to exclude the lowest 5% of streamlines. Resulting masks were used to extract FA and MD as measures of white matter microstructural organization.

Figure 1.

Hippocampal-associated white matter tracts. Prototypical reconstructions of the uncinate fasciculus (blue), fornix (red), and parahippocampal portion of the cingulum bundle (green) are depicted.

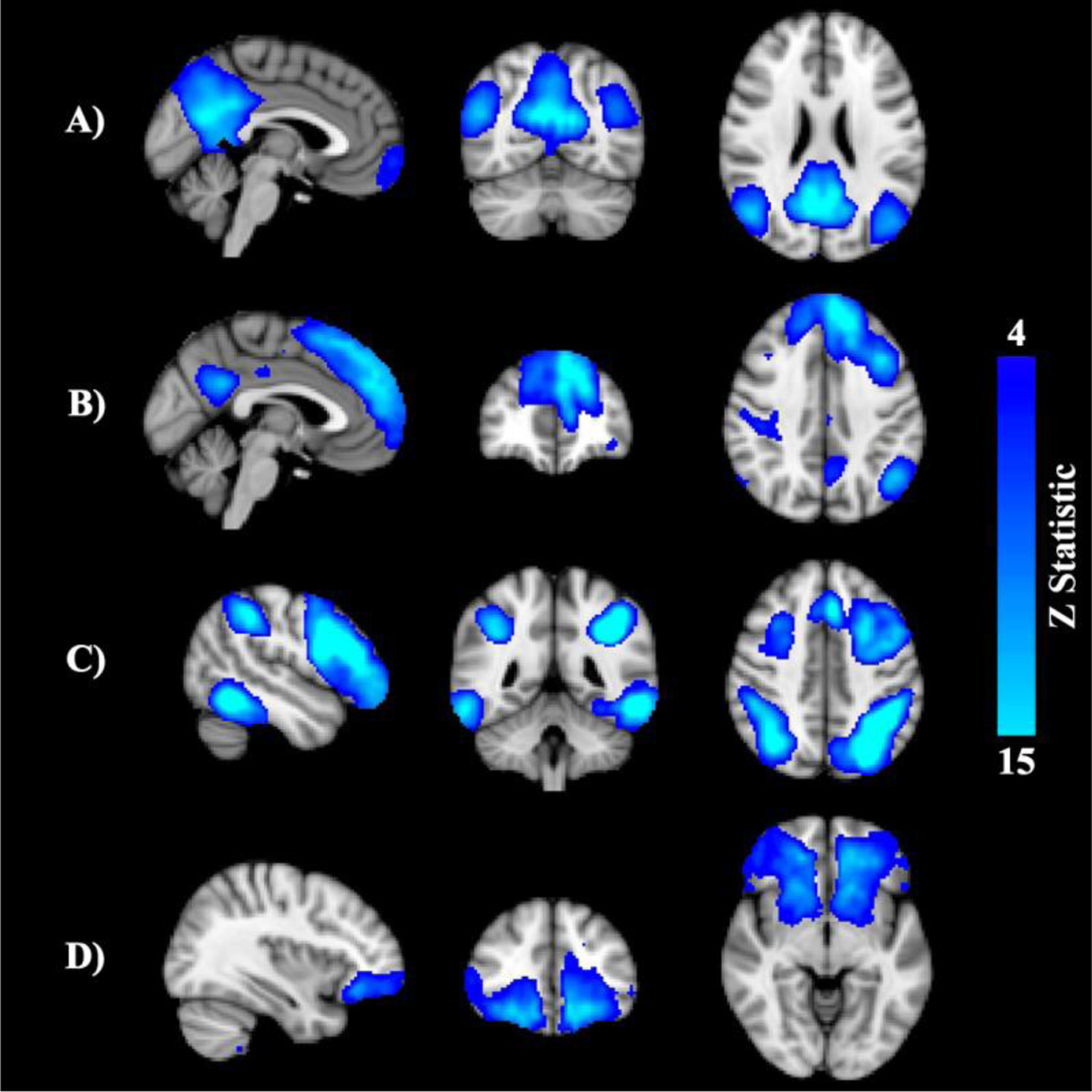

Resting State Networks.

rsfMRI processing was carried out using AFNI (Cox, 1996) and FSL (Smith et al., 2004) based on the Human Connectome Project pipeline (Smith et al., 2013). Following preprocessing, each subject’s 4D dataset underwent linear decomposition through independent component analysis (ICA) using FSL’s MELODIC (Beckmann, DeLuca, Devlin, & Smith, 2005). Results were visually inspected by two independent raters to identify artefactual components (Cohen’s κ for inter-rater agreement=.85), which were regressed out. Denoised data were entered into group ICA and decomposed into 20 independent components, followed by dual regression to yield subject-specific spatial maps and associated time series for each component (Nickerson, Smith, Öngür, & Beckmann, 2017). Networks of interest (i.e., anterior default mode network [DMN], posterior DMN, executive control network, frontoparietal control network; see Figure 2) were identified using a template matching procedure (Greicius et al., 2007). Subject-specific maps for each component of interest were fed into FSL’s randomise (Winkler, Ridgway, Webster, Smith, & Nichols, 2014) for nonparametric permutation inference. Threshold-free cluster enhancement was used to determine statistical significance at p<.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using familywise error.

Figure 2.

Resting state networks of interest: posterior default mode network (DMN; A), anterior DMN (B), frontoparietal network (C), executive control network (D).

Statistical and Power Analysis

Associations between vMWT, TPDT, and RLT performance and demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, education) have been reported elsewhere (Korthauer et al., 2018). Results showed that older age was associated with worse performance on the vMWT and TPDT; thus, associations between imaging metrics and task performance in the present study were assessed using partial correlation, controlling for age. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (v26.0).A power analysis was conducted using G*Power for partial correlation. Assuming α=.05 and a two-tailed test, the study had a power of .95 to detect a moderate-sized effect (ρ=.3). To control for multiple comparisons, we applied a false discovery rate (FDR) of q<.05 for each behavioral task (i.e., vMWT, TPDT, and RLT).

Results

vMWT

Larger left MTL volume was associated with lower distance (r=−.22, p=.02) and heading error (r=−.20, p=.03) on vMWT hidden platform trials as well as more time spent in the goal quadrant on the probe trial (r=.25, p=.01), while larger right MTL volume was associated with lower distance (r=−.24, p=.01) on hidden platform trials (Table 1). Higher left hippocampal MD, a measure of greater microstructural disorganization, was associated with greater latency (r=.18, p=.04) and a trend toward greater distance (r=.17, p=.06) on hidden platform trials and greater probe trial heading error (r=.20, p=.03). Higher right hippocampal MD was associated with greater distance on hidden platform trials (r=.17, p=.05) and greater heading error on the probe trial (r=.17, p=.05). There were no significant associations between 1H MRS measures of hippocampal metabolite concentrations and performance on the vMWT. Regarding MTL-associated white matter tracts, higher FA of the fornix was associated with lower heading error on the vMWT probe trial (r=.19, p=.04), but no other associations were significant. For the resting state networks, connectivity within the executive control network was related to vMWT latency, such that shorter latency on hidden platform trials and more time spent in the goal quadrant on the probe trial was associated with higher connectivity within the right inferior frontal gyrus (p’s<.05). Shorter distance on hidden platform trials was associated with higher connectivity within the left lateral occipital cortex in the right frontoparietal control network (p < .05).

Table 1.

Associations between vMWT and TPDT and MTL Structural Integrity

| vMWT | TPDT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Latency | Total Distance | Total Heading Error | Probe Latency | Probe Distance | Probe Heading Error | Total Trials | Total Errors | |

| Left MTL Volume | r=−.14 | r=−.22* | r=−.20* | r=.25** | r=−.23* | r=.13 | r=.08 | r=.10 |

| Right MTL Volume | r=−.13 | r=−.24* | r=−.08 | r=.03 | r=−.18 | r=−.03 | r=.01 | r=−.02 |

| Right Hippocampus FA | r=.01 | r=.03 | r=.03 | r=−.17 | r=−.04 | r=.07 | r=−.01 | r=.02 |

| Left Hippocampus FA | r=−.03 | r=.07 | r=.04 | r=−.15 | r=.05 | r=.09 | r=−.01 | r=−.01 |

| Left Hippocampus MD | r=.18* | r=.17 | r=.10 | r=.01 | r=.06 | r=.20* | r=.09 | r=.18* |

| Right Hippocampus MD | r=.08 | r=.17* | r=.08 | r=.04 | r=.11 | r=.17* | r=.13 | r=.14 |

Note.

p<.05

p<.01

TPDT

Higher left hippocampal MD was associated with more errors on the TPDT (r=.18, p=.05) (Table 1). There were no significant associations between TPDT performance and MTL volume, 1H MRS measures of hippocampal metabolite concentrations, microstructural organization of MTL-associated white matter tracts, or RSN integrity.

RLT

There were no significant associations between the RLT and prefrontal cortical volume or any other measures of structural and functional integrity (p’s>.05).

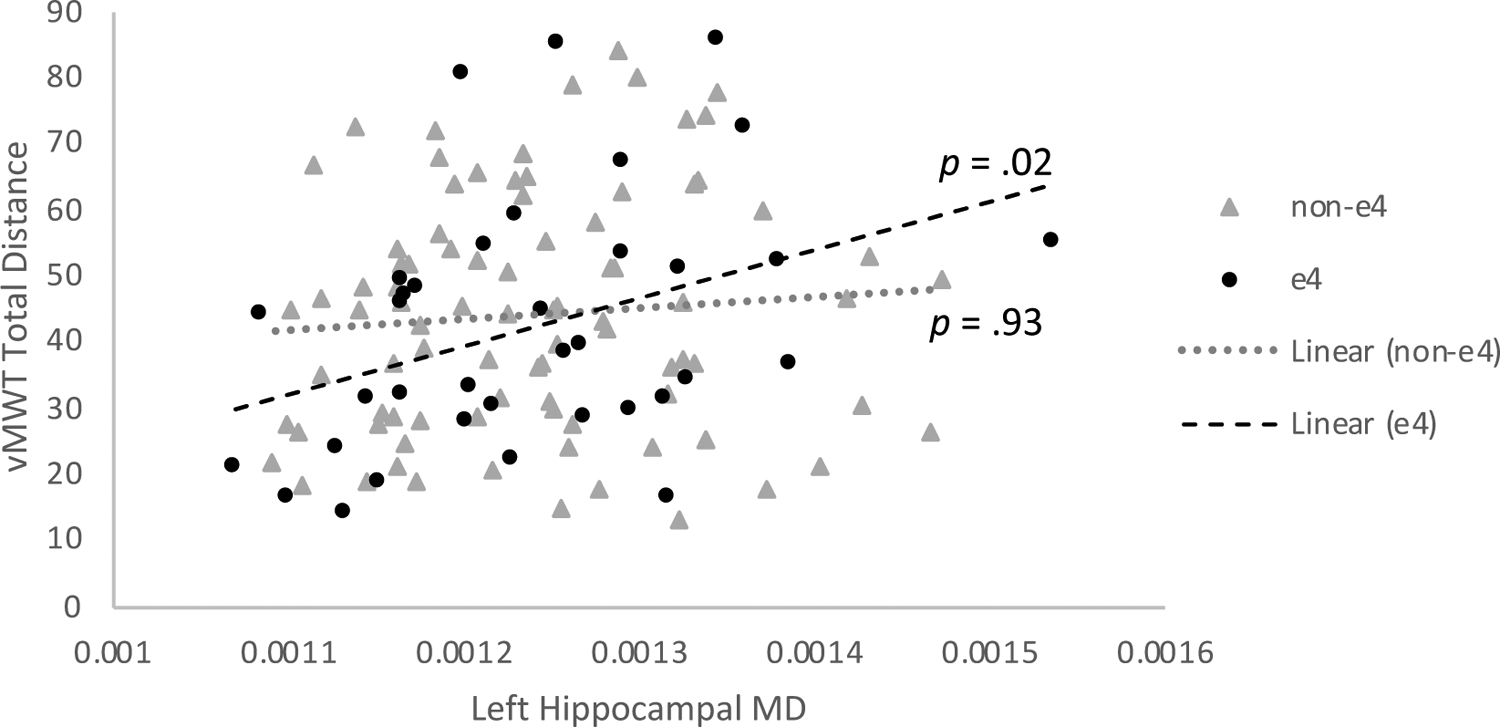

Interactions with ApoE Genotype

We examined ApoE genotype as a moderator of the significant associations reported above. ApoE ε4 genotype moderated the association between left hippocampal MD and vMWT distance traveled on learning trials, R2=.04, F(1, 117)=3.74, p=.05 (Figure 3). Post-hoc correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between hippocampal MD and vMWT performance in ApoE ε4 carriers, r=.38, p=.02, but not in ε4 non-carriers, r=−.01, p=.93. APOE did not significantly moderate any of the other associations examined.

Figure 3.

ApoE genotype moderates the association between hippocampal microstructural integrity and vMWT performance

Given our a priori hypotheses, we set ⍺=05; however, none of the reported associations survived FDR correction for multiple comparisons, q<.05.

Discussion

This is the first known study to demonstrate associations between translational MTL- and PFC-dependent tasks and brain integrity in middle age, a critically important window for demonstrating the clinical utility of potential AD markers. We report a pattern of brain-behavior associations between MTL integrity and performance on the vMWT and TPDT, two translational tasks shown to be dependent on the MTL in non-human animal studies. A major strength of our study is the use of multi-modal MRI to conduct a thorough investigation of MTL and PFC integrity, including regional gray matter volumes, hippocampal microstructural organization, hippocampal biochemistry, microstructural integrity of fronto-temporal white matter tracts, and resting state functional connectivity. We also report that ApoE allele moderates the association between vMWT performance and hippocampal MD (a measure of microstructural integrity), with a significant relationship observed only in ε4-carriers who are at genetic risk for AD. Although none of our reported associations survived correction for multiple comparisons, when examined in light of our a priori hypotheses and the existing literature, this study provides preliminary evidence that the vMWT and TPDT may be inexpensive and non-invasive markers of MTL integrity in middle-aged adults.

Although we examined three cognitive tasks dependent on MTL and prefrontal cortical functioning, the majority of our significant findings were associations between brain integrity and vMWT performance. Specifically, better performance on the vMWT was associated with larger MTL volume, more coherent hippocampal microstructural organization, higher FA within the fornix, and higher connectivity of the inferior frontal gyrus and lateral occipital cortex within key resting state networks. This is consistent with evidence from rodents that vMWT performance depends on intact MTL integrity (Florian & Roullet, 2004; R. G. Morris, Garrud, Rawlins, & O’Keefe, 1982; Redish & Touretzky, 1998). In human imaging studies of younger and older adults, effective vMWT performance has been associated with a broad network of brain regions, including MTL structures, thalamus, caudate nucleus, medial prefrontal cortex, and occipital cortex (Bohbot, Lerch, Thorndycraft, Iaria, & Zijdenbos, 2007; Dahmani & Bohbot, 2015; Driscoll et al., 2003; Korthauer et al., 2016; Moffat, Kennedy, Rodrigue, & Raz, 2007). Our findings add to the evidence that this network of MTL-prefrontal structures also support spatial navigation in middle age.

While we did not assess AD biomarkers directly, we examined APOE genotype as a risk factor for AD, as middle-aged carriers of the ε4 allele have higher amyloid burden (Jack et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2010), more MTL tau pathology (Kok et al., 2009), and lower functional connectivity of the hippocampus (Heise et al., 2014) compared to non-carriers. We found that APOE ε4 carriers with higher hippocampal MD, a measure of microstructural disorganization, performed more poorly on the vMWT whereas non-ε4 carriers showed no significant association. This suggests that APOE ε4 carriers may be more cognitively vulnerable due to early accumulation of AD pathology in the MTL or longstanding differences in organization of memory structures.

We observed few significant brain-behavior associations with the TPDT, another translational MTL-dependent task, or the PFC-dependent RLT. Poorer TPDT performance was associated with higher left hippocampal MD. While the magnitude and direction of this effect were congruent with our hypotheses, it did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. In prior studies, age-associated hippocampal atrophy (Driscoll et al., 2003) and hippocampal lesions (Rickard & Grafman, 1998) have been associated with impaired ability to learn transverse patterning discriminations. There are several possible reasons that we did not observe robust brain-behavior relationships for the TPDT or RLT. Overall performance in this cognitively normal middle-aged population was relatively high (TPDT accuracy IQR = [.83, .92]; RLT accuracy IQR = [.88, .93]). As these tasks were developed for use in older adults and cognitively impaired patients, they may be too easy for middle-aged individuals. Additionally, performance on both the TPDT and RLT benefits from insight learning; once the participant gains insight into the response contingencies, accuracy on remaining trials tends to be high as the person applies the same rules to novel combinations of stimuli. Thus, ceiling effects may have limited the range of performance, reducing power to observe brain-behavior correlations.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design makes it impossible to evaluate intra-individual cognitive trajectories, which are likely more informative than a single time point. Future longitudinal studies are needed to identify whether baseline performance on these tasks are associated with age-related cognitive decline and conversion to MCI or dementia. Additionally, though the study was adequately powered, using multi-modal imaging increased the number of overall statistical comparisons. This raises concern about type 1 error, and none of the reported associations survived correction for multiple comparisons. Despite these limitations and the need to interpret results with caution, we believe that this study provides important information about the neural underpinnings of three translational paradigms that may serve as potential cognitive markers of AD.

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, we report a pattern of brain-behavior associations between multimodal measures of functional and structural brain integrity and performance on the vMWT and TPDT. This is the first known study to investigate the neural underpinnings of performance on MTL- or PFC-dependent tasks in a cognitively normal, middle-aged sample. Although the effects were modest and did not survive correction for multiple comparisons, our findings add to the literature suggesting that the vMWT may be a non-invasive cognitive marker of MTL integrity with potential utility for detecting early AD-associated change.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) R00-AG032361 (Driscoll) and F31-AG050407 (Korthauer).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with guidelines set by the institutional review boards at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Medical College of Wisconsin.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- Acosta-Cabronero J, & Nestor PJ (2014). Diffusion tensor imaging in Alzheimer’s disease: insights into the limbic-diencephalic network and methodological considerations. Front Aging Neurosci, 6, 266. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlien IK, & Fjell AM (2014). Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroscience. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JL, & Sotiropoulos SN (2016). An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage, 125, 1063–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova E, Parslow D, Brammer M, Dawson GR, Jackson SH, & Morris RG (2009). Age-related neural activity during allocentric spatial memory. Memory, 17(2), 125–143. doi: 10.1080/09658210802077348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astur RS, Ortiz ML, & Sutherland RJ (1998). A characterization of performance by men and women in a virtual Morris water task: a large and reliable sex difference. Behav Brain Res, 93(1–2), 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Bartlett JW, van de Pol LA, Loy CT, Scahill RI, Frost C, … Fox NC (2009). A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging, 30(11), 1711–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, & Smith SM (2005). Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 360(1457), 1001–1013. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TE, Berg HJ, Jbabdi S, Rushworth MF, & Woolrich MW (2007). Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: What can we gain? Neuroimage, 34(1), 144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG, Clare S, … Smith SM (2003). Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med, 50(5), 1077–1088. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohbot VD, Lerch J, Thorndycraft B, Iaria G, & Zijdenbos AP (2007). Gray matter differences correlate with spontaneous strategies in a human virtual navigation task. J Neurosci, 27(38), 10078–10083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1763-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, McDonald CR, … Salmon DP (2014). Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and progression rates. J Alzheimers Dis, 42(1), 275–289. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell BR, Johnson LL, Holroyd T, Carver FW, & Grillon C (2008). Human hippocampal and parahippocampal theta during goal-directed spatial navigation predicts performance on a virtual Morris water maze. J Neurosci, 28(23), 5983–5990. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5001-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW (1996). AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res, 29(3), 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmani L, & Bohbot VD (2015). Dissociable contributions of the prefrontal cortex to hippocampus- and caudate nucleus-dependent virtual navigation strategies. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 117, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, & Sereno MI (1999). Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage, 9(2), 179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP, Pradhaban G, Liu X, Khandji A, De Santi S, Segal S, … de Leon MJ (2007). Hippocampal and entorhinal atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: prediction of Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 68(11), 828–836. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256697.20968.d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RM, Bradley KM, Budge MM, Styles P, & Smith AD (2002). Longitudinal quantitative proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, 125(Pt 10), 2332–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Hamilton DA, Petropoulos H, Yeo RA, Brooks WM, Baumgartner RN, & Sutherland RJ (2003). The aging hippocampus: cognitive, biochemical and structural findings. Cereb Cortex, 13(12), 1344–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Hamilton DA, Yeo RA, Brooks WM, & Sutherland RJ (2005). Virtual navigation in humans: the impact of age, sex, and hormones on place learning. Horm Behav, 47(3), 326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows LK, & Farah MJ (2003). Ventromedial frontal cortex mediates affective shifting in humans: evidence from a reversal learning paradigm. Brain, 126(Pt 8), 1830–1837. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, … Dale AM (2002). Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron, 33(3), 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, Halgren E, Ségonne F, Salat DH, … Dale AM (2004). Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex, 14(1), 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian C, & Roullet P (2004). Hippocampal CA3-region is crucial for acquisition and memory consolidation in Morris water maze task in mice. Behav Brain Res, 154(2), 365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res, 12(3), 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PM, Lambert C, Sunderland T, & Parasuraman R (2005). Effects of apolipoprotein E genotype on spatial attention, working memory, and their interaction in healthy, middle-aged adults: results From the National Institute of Mental Health’s BIOCARD study. Neuropsychology, 19(2), 199–211. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.2.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, Glover GH, Solvason HB, Kenna H, … Schatzberg AF (2007). Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol Psychiatry, 62(5), 429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise V, Filippini N, Trachtenberg AJ, Suri S, Ebmeier KP, & Mackay CE (2014). Apolipoprotein E genotype, gender and age modulate connectivity of the hippocampus in healthy adults. Neuroimage, 98, 23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, … Dubois B (2016). A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology, 87(5), 539–547. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Mielke MM, … Petersen RC (2015). Age, Sex, and APOE ε4 Effects on Memory, Brain Structure, and β-Amyloid Across the Adult Life Span. JAMA Neurol, 72(5), 511–519. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, & Churchwell JC (2011). An analysis of rat prefrontal cortex in mediating executive function. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 96(3), 417–431. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi K, Morikawa M, Taoka T, Nagashima T, Yamauchi T, Makinodan M, … Kishimoto T (2009). Abnormalities of the uncinate fasciculus and posterior cingulate fasciculus in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease: a diffusion tensor tractography study. Brain Res, 1287, 184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok E, Haikonen S, Luoto T, Huhtala H, Goebeler S, Haapasalo H, & Karhunen PJ (2009). Apolipoprotein E-dependent accumulation of Alzheimer disease-related lesions begins in middle age. Ann Neurol, 65(6), 650–657. doi: 10.1002/ana.21696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthauer LE, Awe E, Frahmand M, & Driscoll I (2018). Genetic Risk for Age-Related Cognitive Impairment Does Not Predict Cognitive Performance in Middle Age. J Alzheimers Dis, 64(2), 459–471. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthauer LE, Nowak NT, Moffat SD, An Y, Rowland LM, Barker PB, … Driscoll I (2016). Correlates of virtual navigation performance in older adults. Neurobiol Aging, 39, 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laczó J, Andel R, Vyhnalek M, Vlcek K, Magerova H, Varjassyova A, … Hort J (2010). Human analogue of the morris water maze for testing subjects at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis, 7(1–3), 148–152. doi: 10.1159/000289226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laczó J, Vlcek K, Vyhnálek M, Vajnerová O, Ort M, Holmerová I, … Hort J (2009). Spatial navigation testing discriminates two types of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Behav Brain Res, 202(2), 252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S (1988). Dementia rating scale (DRS). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler-Baddeley C, Baddeley RJ, Jones DK, Aggleton JP, & O’Sullivan MJ (2013). Individual differences in fornix microstructure and body mass index. PLoS One, 8(3), e59849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Kennedy KM, Rodrigue KM, & Raz N (2007). Extrahippocampal contributions to age differences in human spatial navigation. Cereb Cortex, 17(6), 1274–1282. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, & Mintun MA (2010). APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol, 67(1), 122–131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, & O’Keefe J (1982). Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature, 297(5868), 681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson LD, Smith SM, Öngür D, & Beckmann CF (2017). Using Dual Regression to Investigate Network Shape and Amplitude in Functional Connectivity Analyses. Front Neurosci, 11, 115. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RK, Moses SN, Riggs L, & Ryan JD (2012). The hippocampus supports multiple cognitive processes through relational binding and comparison. Front Hum Neurosci, 6, 146. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostreicher ML, Moses SN, Rosenbaum RS, & Ryan JD (2010). Prior experience supports new learning of relations in aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 65B(1), 32–41. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnetti L, Lowenthal DT, Presciutti O, Pelliccioli GP, Palumbo R, Gobbi G, … Senin U (1996). 1H-MRS, MRI-based hippocampal volumetry, and 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT in normal aging, age-associated memory impairment, and probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc, 44(2), 133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW (2001). Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed, 14(4), 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish AD, & Touretzky DS (1998). The role of the hippocampus in solving the Morris water maze. Neural Comput, 10(1), 73–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard TC, & Grafman J (1998). Losing their configural mind. Amnesic patients fail on transverse patterning. J Cogn Neurosci, 10(4), 509–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM (2002). Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp, 17(3), 143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Beckmann CF, Andersson J, Auerbach EJ, Bijsterbosch J, Douaud G, … Consortium, W.-M. H. (2013). Resting-state fMRI in the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage, 80, 144–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, … Matthews PM (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage, 23 Suppl 1, S208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Witter MP, Lein ES, & Moser EI (2014). Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat Rev Neurosci, 15(10), 655–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Liang M, Wang L, Tian L, Zhang X, Li K, & Jiang T (2007). Altered functional connectivity in early Alzheimer’s disease: a resting-state fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp, 28(10), 967–978. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zang Y, He Y, Liang M, Zhang X, Tian L, … Li K (2006). Changes in hippocampal connectivity in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from resting state fMRI. Neuroimage, 31(2), 496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, & Nichols TE (2014). Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage, 92, 381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei M, Beckmann CF, Binnewijzend MA, Schoonheim MM, Oghabian MA, Sanz-Arigita EJ, … Barkhof F (2013). Functional segmentation of the hippocampus in the healthy human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage, 66, 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]