Abstract

Background:

Although the recommended minimal examined lymph node (ELN) number in rectal cancer (RC) is 12, this standard remains controversial because of insufficient evidence. We aimed to refine this definition by quantifying the relationship between ELN number, stage migration and long-term survival in RC.

Methods:

Data from a Chinese multi-institutional registry (2009-2018) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (2008-2017) on stages I–III resected RC were analysed to determine the relationship between ELN count, stage migration, and overall survival (OS) using multivariable models. The series of odds ratios (ORs) for negative-to-positive node stage migration and hazard ratios (HRs) for survival with more ELNs were fitted using a Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) smoother, and structural breakpoints were determined using the Chow test. The relationship between ELN and survival was evaluated on a continuous scale using restricted cubic splines (RCS).

Results:

The distribution of ELN count between the Chinese registry (n=7694) and SEER database (n=21 332) was similar. With increasing ELN count, both cohorts exhibited significant proportional increases from node-negative to node-positive disease (SEER, OR, 1.012, P<0.001; Chinese registry, OR, 1.016, P=0.014) and serial improvements in OS (SEER: HR, 0.982; Chinese registry: HR, 0.975; both P<0.001) after controlling for confounders. Cut-point analysis showed an optimal threshold ELN count of 15, which was validated in the two cohorts, with the ability to properly discriminate probabilities of survival.

Conclusions:

A higher ELN count is associated with more precise nodal staging and better survival. Our results robustly conclude that 15 ELNs are the optimal cut-off point for evaluating the quality of lymph node examination and stratification of prognosis.

Keywords: examined lymph node count, rectal cancer, stage migration, survival, threshold

Introduction

Highlights

Accurate lymph node examination is crucial for cancer staging and prognostic prediction for rectal cancer (RC).

Fifteen examined lymph nodes (ELNs) are the optimal cut-off point for RC staging.

Examination of a larger number of ELNs could contribute to improved survival for RC patients.

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for rectal cancer (RC)1. Cancer staging plays a key role in the choice of treatment strategy postoperatively; it also helps predict the long-term survival of patients with RC2. Presently, the TNM staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is the most recognised system for classifying the extent of the spread of colorectal cancer3. The examined lymph node (ELN) is associated with the prognosis of RC patients and a minimum of 12 ELNs has been considered the standard yield in colorectal cancer by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and AJCC4. The prognostic impact of these criteria has been confirmed in several clinical studies5–7. However, survival prediction by the N category is always affected by stage migration because the total number of ELNs could contribute to the change in metastatic lymph nodes, which leads to up-migration or down-migration in the pathological N category8. Therefore, to achieve optimum reliability of the pathological N category, the optimal number of ELN to be surgically removed and pathologically examined needs to be carefully determined9,10.

Owing to the differences in various methodological approaches and study populations, the recommended optimal number of ELNs is significantly heterogenous in RC11,12. Furthermore, ELN count is affected by a single factor or a combination of factors, including characteristics of the primary tumour, status of immune activation, extent of surgical resection, hospital volume and pathological examine methods, which could influence stage migration and tumour staging of RC patients13. Therefore, it is difficult to draw a favourable conclusion on the optimal ELN count from a small sample size or a single-centre study10,14. As a result, optimal ELN count needs to be determined and validated in large population-based cohorts.

In the present study, we hypothesised that there was an optimal ELN count to be examined for accurate staging and prognostic prediction in RC. Hence, we performed this longitudinal international cohort study to explore the ELN count after RC resection and assess the effects of ELN count on tumour stage migration and the long-term survival of RC patients.

Method

Study population

Data from a multi-institutional registry of patients with RC who underwent surgical resection between January 2009 and December 2018 at the departments of colorectal surgery at five medical institutions in China were collected. ELNs were harvested during surgical resection of the RC, and the tissue was examined postoperatively by pathologists. The ELN count was determined based on pathological findings. The patients were staged according to TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th edition. This study was retrospectively registered with the Clinical Trials (NCT05572151). This work has been reported in line with the STROCSS (strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case–control studies in surgery) criteria15 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A757).

In addition, data were collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, an open-access database containing patient demographics, tumour data, perioperative treatment data, and survival data. The database includes ~28% of the U.S. population, with patient-level data abstracted from 18 geographically diverse populations that represent rural, urban, and regional populations. Data on RC cases diagnosed between January 2008 and December 2017 in the SEER database were extracted to match the time span of the Chinese cohort. Patients were uniformly reviewed and staged according to TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th edition. The details were retrieved using SEER*Stat version 8.1.5.

Patient selection

Because preoperative chemo/radiotherapy is a common cause of ELN shrinkage16, patients who received preoperative therapy were excluded from this study. Patients with stages I–III RC who underwent surgical resection for the first primary RC with at least one ELN were eligible. Patients with missing ELN counts or clinical features were excluded. Patients information (age, sex and year of diagnosis), tumour data (TNM stage, histology, size and differentiation), treatments (resection type and chemotherapy) and outcome variables (follow-up time and survival status) were obtained from the SEER and China registries.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were presented as whole numbers and proportions, and continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). The 5-year overall survival (OS) of the study population was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in OS were assessed using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to determine the effect of ELN count on OS and to visualise survival curves, which were adjusted for other significant prognostic factors (age, sex, tumour stage, grade, histology type, tumour size and adjuvant chemotherapy).

In addition, the relationships between ELN and OS were evaluated on a continuous scale with restricted cubic splines (RCS) based on a multivariable Cox model with three knots at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles of ELN. The use of RCS has been widely described as a valid strategy for analysing the relationship between survival and independent variables17. RCS are a smoothly joined sum of polynomial functions that do not assume linearity of the relationship between variables and the response (i.e. survival)18. In addition, the use of RCS allows the identification of the risk function inflexion point (i.e. threshold)19.

Based on the assumption that more ELNs present a greater opportunity to identify positive ELNs, a binary logistic regression model was used to assess stage migration through the correlation of the ELN number and proportion of each node stage category (node-negative versus node-positive)20 after adjusting for other potential confounders associated with ELN count and node stage.

The curves of odds ratios (ORs; stage migration) of each ELN count compared with one ELN (as a reference) and the curves of hazard ratios (HRs; OS) of each ELN count compared with five or fewer ELNs (as a reference) were fitted using the Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) smoother with a bandwidth of 2/3 (default)21. Afterwards, structural breakpoints were determined by the Chow test and piecewise linear regression with the use of ‘strucchange’ and ‘segmented’ R packages. The breakpoints were considered the threshold for clinical impact. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.4; http://www.r-project.org). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and distribution of ELN

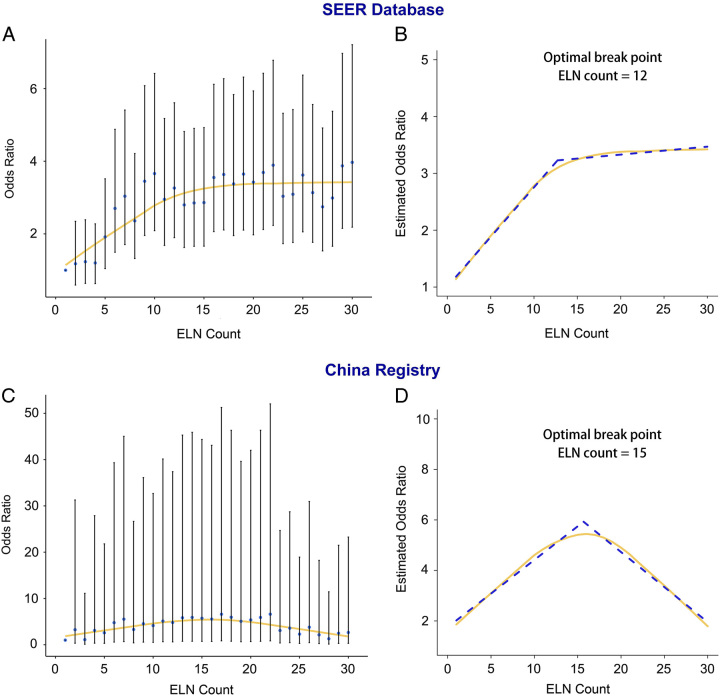

A total of 21 332 and 7694 patients with RC in the SEER and Chinese cohorts, respectively, who met the eligibility criteria were included in this study. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of each cohort. Of these patients, the proportion of men was greater than that of women in both the Chinese (60.4%, 4649/7694) and SEER (55.8%, 11 907/21 332) cohorts. The distribution of ELN counts (Fig. 1) was largely consistent between the cohorts; the median number of ELN counts in the Chinese cohort was 15 (IQR, 13–19) and that in the SEER cohort was 16 (IQR, 12–22). Besides, at least 12 lymph nodes (LNs) were retrieved in most patients in both the Chinese (85.8%, 6598/7694) and SEER cohorts (81.9%, 17 475/21 332).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in SEER database and China registry.

| SEER database | China registry | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N (%) | N (%) |

| Total | 21 332 (100) | 7694 (100) |

| Age, years | ||

| <65 | 9796 (45.9) | 4900 (63.7) |

| ≥65 | 11 534 (54.1) | 2794 (36.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 9425 (44.2) | 3045 (39.6) |

| Male | 11 907 (55.8) | 4649 (60.4) |

| AJCC T stage | ||

| T1–T2 | 9476 (44.4) | 2337 (30.4) |

| T3–T4 | 11 856 (55.6) | 5357 (69.6) |

| AJCC N stage | ||

| N0 | 13 933 (65.3) | 5068 (65.9) |

| N1/2 | 7399 (34.7) | 2626 (34.1) |

| AJCC stage | ||

| Stage 1 | 7993 (37.5) | 1879 (24.4) |

| Stage 2 | 5940 (27.8) | 3189 (41.4) |

| Stage 3 | 7399 (34.7) | 2626 (34.1) |

| Grade | ||

| Well/moderately | 18 501 (86.7) | 6791 (88.3) |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 2831 (13.3) | 903 (11.7) |

| Histology type | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 007 (93.8) | 6883 (89.5) |

| Mucinous/signet | 1062 (5.0) | 672 (8.7) |

| Others | 263 (1.2) | 139 (1.8) |

| Tumour size, cm (IQR) | 3.8 (2.5–5.2) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| No/unknown | 16 012 (75.1) | 3387 (44.0) |

| Yes | 5320 (24.9) | 4307 (56.0) |

| Median ELN count (IQR) | 16 (12–22) | 15 (13–19) |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ELN, examined lymph node; IQR, interquartile range; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the number of harvested lymph nodes in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (A) and the China registry (B). ELN, examined lymph node.

Number of ELNs and stage migration

The association of ELNs with the detection rate of positive LNs was assessed to clarify the relationship between ELN count and stage migration. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A758) a higher number of ELNs was correlated with a higher LN positivity rate. Furthermore, after adjusting for potential confounders (age, sex, T stage, N stage, grade, histology and tumour size), both cohorts showed a significantly proportional increase in N stage (from N0 to N1 and N2) with increasing ELN count (Chinese registry: OR, 1.016; 95% CI, 1.003–1.029; P=0.014; SEER: OR, 1.012; 95% CI, 1.009–1.015; P<0.001; Table 2, and Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A759).

Table 2.

Effect of number of examined lymph nodes on stage migration and patient survival.

| Stage migration | Overall survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| SEER database | ||||||

| Overall | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.98–0.99 | <0.001 |

| Node-negative disease | – | – | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 | <0.001 | |

| Node-positive disease | – | – | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99 | <0.001 | |

| China registry | ||||||

| Overall | 1.02 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.014 | 0.98 | 0.96–0.99 | <0.001 |

| Node-negative disease | – | – | 0.98 | 0.96–1.00 | 0.014 | |

| Node-positive disease | – | – | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.005 | |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio.

Number of ELNs and OS

After controlling for other prognostic factors, including age, sex, T stage, N stage, grade, histology, tumour size and adjuvant chemotherapy, a higher ELN number was positively correlated with better OS in patients in the SEER (HR, 0.982; 95% CI, 0.979–0.985; P<0.001) and in the Chinese cohorts (HR, 0.975; 95% CI, 0.963–0.987; P<0.001), with a similar reduction in mortality risk. Notably, a consistent trend was observed (Table 2 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A759) among patients with node-negative (N0) disease (SEER: HR, 0.978; 95% CI, 0.974–0.982; P<0.001; Chinese registry: HR, 0.980; 95% CI, 0.964–0.996; P=0.014) and those with node-positive (N1 and N2) disease (SEER: HR, 0.987; 95% CI, 0.983–0.991; P<0.001; Chinese registry: HR, 0.972; 95% CI, 0.954–0.991; P=0.005).

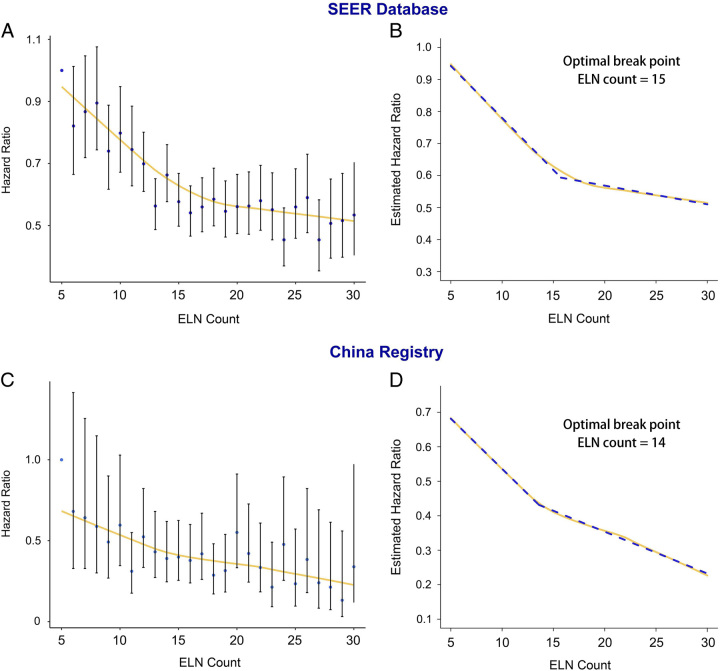

Cut-point analysis

For a more rigorous evaluation, a Cox model with RCS was created to flexibly model and visualise the relationship between ELN and OS risk (Fig. 2). The results were adjusted for age, sex, T stage, grade, histology, tumour size, and adjuvant chemotherapy. The relationship between ELN on a continuous scale and the risk of OS was L-shaped. The risk of OS decreased rapidly until ~15 ELN counts and afterwards, the risk was relatively flat (P for nonlinearity <0.001) both cohorts. For patients with an ELN count <15, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio for OS was 0.957 (95% CI, 0.947–0.968, P<0.001) in the SEER cohort and 0.932 (95% CI, 0.898–0.967, P<0.001) in the Chinese cohort. For patients with an ELN count of at least 15, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio for OS was 0.993 (95% CI, 0.989–0.997, P=0.001) in the SEER cohort and 0.992 (95% CI, 0.975–1.008, P=0.322) in the Chinese cohort.

Figure 2.

Association between ELN count and survival using restricted cubic splines model in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and the China registry. Hazard ratios are indicated by solid lines and 95% CIs by shaded areas. The range of ELN count was restricted to 1–59 in the SEER database (1–55 in the China registry) because predictions greater than 59 and 55 (95th percentile) are based on too few data points. ELN, examined lymph node.

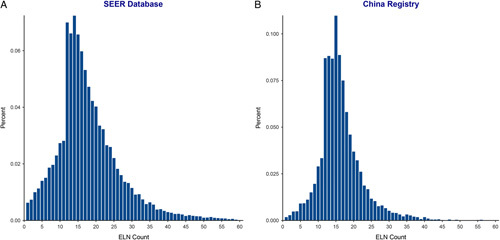

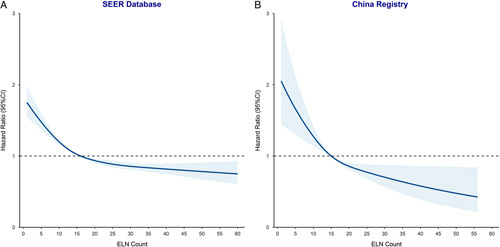

Figures 3 and 4 show the fitting curves and corresponding structural breakpoints for the OR of stage migration and HR of OS after adjusting for other potential confounders in the two cohorts. All breakpoints were essentially consistent with each other (varied from 12 to 15). Because survival is the most crucial issue and for representativeness and generalisability, we recommend 15 ELNs as the optimal threshold based on the RCS curve in the two cohorts and the fitting curve of HR, which was generated from the SEER cohort.

Figure 3.

Associations of odds ratio for stage migration (negative-to-positive node) and number of examined lymph nodes. Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) smoothing fitting curves with a fitting bandwidth of 2/3 are shown in yellow, and the structural breakpoint was determined with the use of the Chow test in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (A and B) and the China registry (C and D). ELN, examined lymph node.

Figure 4.

Associations of the hazard ratio for overall survival and number of examined lymph nodes. Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) smoothing fitting curves with a fitting bandwidth of 2/3 are shown in yellow and the structural breakpoint was determined with use of the Chow test in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (A and B) and the China registry (C and D). ELN, examined lymph node.

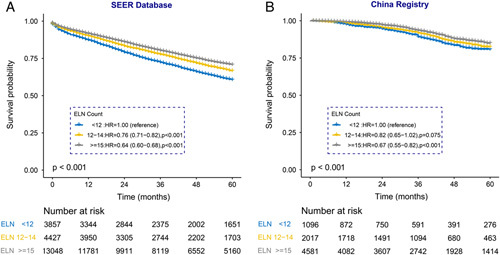

Comparison of optimal thresholds

As international guidelines have uniformly adopted 12 ELNs as the proposed threshold for colorectal cancer, which originated from the 1990 World Congress of Gastroenterology, and the ELN count was divided into three populations (ELN<12, ELN: 12–14, ELN≥15) into two cohorts. Survival analysis confirmed a significantly reduced all-cause mortality hazard for patients with at least 15 ELNs harvested in two cohorts (SEER database: HR12–14, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.71–0.82; P<0.001; HR≥15, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.60–0.68; P<0.001; Chinese registry: HR12–14, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.65–1.02; P=0.075; HR≥15, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.55–0.82; P<0.001) after adjusting for other prognostic factors (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the association remained significant in declared node-negative (SEER database: HR12–14, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69–0.84; P<0.001; HR≥15, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.56–0.67; P<0.001; Chinese registry: HR12–14, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.73–1.42; P=0.918; HR≥15, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.49–0.92; P=0.012) and node-positive patients (SEER database: HR12–14, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.70–0.89; P<0.001; HR≥15, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.63–0.77; P<0.001; Chinese registry: HR12–14, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.51–0.94; P=0.017; HR≥15, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.53–0.90; P=0.006) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A760).

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival are shown for different groups of ELNs in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and the China registry. ELN, examined lymph node.

Notably, although patients with at least 15 LNs harvested had better survival outcomes than those with <12 LNs, no significant differences in OS were observed between patients with 12–14 LNs harvested and those with <12 LNs in the Chinese cohort and node-negative disease patients.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the largest population-based study of two real-world international cohorts. Although several studies have identified the optimal ELN number for colorectal cancer, most studies did not consider RC as an isolated tumour site22,23. In addition, a large number of studies have focused on RC patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy, and no relevant study has explored the optimal ELN number in RC patients without neoadjuvant therapy based on a large population-based study14,24.

Our findings indicated that a minimum of 15 ELNs were associated with increased detection of metastatic ELN and improved survival for RC patients, which was confirmed in the U.S. and Chinese large population-based cohorts. The total number of ELN is considered a powerful indicator of stage migration and survival prediction in RC patients in clinical practice. The data provide strong support for retrieving a minimum of 15 ELNs in the context of potentially curative proctectomy for RC. According to our findings, ELNs count was associated with a decreased risk of stage migration and improved long-term survival in RC patients, which encourages surgeons and pathologists to pursue a maximal effort of ELNs.

The strengths of the present study include a long follow-up period as well as a large observational population with relatively homogeneous treatment exposure identified from the SEER database and Chinese multi-institutional registry. In addition, the statistical methods used for the analysis were essential for interpreting the results. In the present study, several key statistical methods were used to obtain strong evidence for the selection of the optimal number of ELNs for RC, which could provide a more valuable reference for the treatment of patients with RC in clinical practice.

In the present study, the total number of ELNs was associated with stage migration, which was confirmed by the consistent positive correlation between a larger ELN number and a higher proportion of advanced N categories in the U.S. and Chinese populations. It is known that the detection of more ELNs in rectal specimens could increase the likelihood of positive ELNs being detected, leading to an accurate N stage and the necessary implementation of adjuvant chemotherapy, thereby promoting the long-term survival of RC patients. Therefore, in the U.S. and Chinese cohorts, there were similar positive trends between a larger number of ELNs and better OS in RC patients with both metastatic and non-metastatic ELNs.

Stage migration due to insufficient ELNs may partly explain the improved survival of patients with a larger number of ELN. In addition to the reason for stage migration, a larger number of ELNs is related to a stronger anti-tumour immune response, which is considered a prognostic predictor for cancer patients25. Robust anti-tumour immune responses will lead to LNs enlargement, which is easily detected by surgeons and pathologists in clinical practice. This also partly explains our previous findings that LNs were more likely to be detected in younger patients than in older patients because of the stronger anti-tumour immune responses of the younger hosts26. Therefore, the examination of a larger number of ELNs may contribute to improved survival due to a stronger immune response27. Although the interplay between tumour biology and host that may confer this survival improvement needs to be explained, native host’s anti-tumour immune response may play a key role28. Further studies are warranted to explore the biological reasons underlying the prognosis of patients with ELNs and anti-tumour immune responses.

However, several limitations of this study should be noted when interpreting the results. First, although the two international cohorts provided large population-based analyses with long-term follow-up information enabling the assessment of the association between optimal ELN and patient outcome after adjusting for several confounding factors, we cannot overcome the retrospective nature of selection bias. Second, it is well known that the number of ELN is affected by the shared responsibility of both surgeons and pathologists. However, because of the retrospective design of the study, information regarding the surgeon for lymphadenectomy and the pathological evaluation of postoperative rectal specimen could not be included and analysed in this study, which led to the inability to evaluate the influence of surgeons and pathologists on the number of ELN. Third, the change in the number of ELN over time contributed to unavoidable bias because of the long period of spanning years in these two cohorts. However, we performed several statistical methods and checks to evaluate the feasibility of our findings. Fourth, because this study was based on two real-world cohorts, the surgical procedures and pathological assessments of ELNs vary among surgeons, pathologists and regions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a minimum of 15 ELNs was associated with more accurate tumour staging and favourable long-term survival of RC patients. We recommend 15 ELNs as the optimal cut-off point for the assessment of the quality of postoperative pathological examination and prognostic stratification for RC patients. The novel optimal cut-off point has imposed an increased requirement for the routinely used AJCC nodal evaluation and has demonstrated compelling results based on external validation in a large cohort of the Chinese population, which suggest wide clinical applicability in different populations of RC patients.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Approval No. 17-116/1439).

Source of funding

This study was supported by the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (Grant Number: SZSM201911012), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 82100598 and 82072750), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2021JJA140081), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (48804), Shanghai Sailing Program (Grant Number: 21YF1459300), and National Key R&D Program for Young Scientists (Grant Number: 2022YFC2505700).

Author contribution

X.G.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and study design; S.J.: data curation, data analysis, and writing; R.W. and G.Y.: data curation, statistical analysis, and writing; J.L., D.M., S.L., and G.W.: data collections; R.W., W.Z., L.H., L.Z., Z.L., and E.Z.: data analysis; W.Z. and X.W.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: https://register.clinicaltrials.gov/.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: NCT05572151.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT05572151.

Guarantor

Xu Guan.

Data availability statement

All data generated during the study process are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) for their kind work in data collection and delivery.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

X.G., S.J., R.W. and G.Y. contributed equally to this study.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 7 July 2023

Contributor Information

Xu Guan, Email: drguanxu@163.com.

Shuai Jiao, Email: jiaoshuai1114@163.com.

Rongbo Wen, Email: wrb1213@hotmail.com.

Guanyu Yu, Email: yuguanyu0451@163.com.

Jungang Liu, Email: liujungang@gxmu.edu.cn.

Dazhuang Miao, Email: drmiao1988@hotmail.com.

Ran Wei, Email: 251447286@qq.com.

Weiyuan Zhang, Email: weiyuanzhang817@163.com.

Liqiang Hao, Email: 13918125628@139.com.

Leqi Zhou, Email: richard12@126.com.

Zheng Lou, Email: louzhengpro@126.com.

Shucheng Liu, Email: liushucheng_10@163.com.

Enliang Zhao, Email: zhaoenliang666@163.com.

Guiyu Wang, Email: guiywang@163.com.

Wei Zhang, Email: weizhang2000cn@163.com.

Xishan Wang, Email: wxshan1208@126.com.

References

- 1.Keller DS, Berho M, Perez RO, et al. The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;17:414–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans J, Patel U, Brown G. Rectal cancer: primary staging and assessment after chemoradiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2011;21:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, et al. Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton CC, Greene FL. The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raoof M, Nelson RA, Nfonsam VN, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node yield in ypN0 rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2016;103:1731–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mekenkamp LJ, van Krieken JH, Marijnen CA, et al. Lymph node retrieval in rectal cancer is dependent on many factors – the role of the tumor, the patient, the surgeon, the radiotherapist, and the pathologist. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1547–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betge J, Harbaum L, Pollheimer MJ, et al. Lymph node retrieval in colorectal cancer: determining factors and prognostic significance. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:991–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong SH, Lee HJ, Ahn HS, et al. Stage migration effect on survival in gastric cancer surgery with extended lymphadenectomy: the reappraisal of positive lymph node ratio as a proper N-staging. Ann Surg 2012;255:50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi HK, Law WL, Poon JT. The optimal number of lymph nodes examined in stage II colorectal cancer and its impact of on outcomes. BMC Cancer 2010;10:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng H, Lyu Z, Liang W, et al. Optimal examined lymph node count in node-negative colon cancer should be determined. Future Oncol 2021;17:3865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein NS. Lymph node recoveries from 2427 pT3 colorectal resection specimens spanning 45 years: recommendations for a minimum number of recovered lymph nodes based on predictive probabilities. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan DKH, Tan KK. Lower lymph node yield following neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer has no clinical significance. J Gastrointest Oncol 2019;10:42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballanamada Appaiah NN, Rafaih Iqbal M, Kafayat Lesi O, et al. Clinicopathological factors affecting lymph node yield and positivity in left-sided colon and rectal cancers. Cureus 2021;13:e19115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeo CS, Syn N, Liu H, et al. A lower cut-off for lymph node harvest predicts for poorer overall survival after rectal surgery post neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. World J Surg Oncol 2020;18:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathew G, Agha R. STROCSS 2021: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case–control studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asli LM, Johannesen TB, Myklebust TA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer and impact on outcomes – a population-based study. Radiother Oncol 2017;123:446–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salazar MC, Rosen JE, Wang Z, et al. Association of delayed adjuvant chemotherapy with survival after lung cancer surgery. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauthier J, Wu QV, Gooley TA. Cubic splines to model relationships between continuous variables and outcomes: a guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant 2020;55:675–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molinari N, Daures JP, Durand JF. Regression splines for threshold selection in survival data analysis. Stat Med 2001;20:237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med 1985;312:1604–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang W, He J, Shen Y, et al. Impact of examined lymph node count on precise staging and long-term survival of resected non-small-cell lung cancer: a population study of the US SEER database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaker H, Hildebrandt B, Riess H, et al. Lymph node count and prognosis in colorectal cancer: the influence of examination quality. Int J Cancer 2015;136:1957–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vather R, Sammour T, Kahokehr A, et al. Lymph node evaluation and long-term survival in Stage II and Stage III colon cancer: a national study. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Zhou M, Yang J, et al. Increased lymph node yield indicates improved survival in locally advanced rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Med 2019;8:4615–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinato DJ, Howlett S, Ottaviani D, et al. Association of prior antibiotic treatment with survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1774–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan X, Chen W, Li S, et al. Alterations of lymph nodes evaluation after colon cancer resection: patient and tumor heterogeneity should be taken into consideration. Oncotarget 2016;7:62664–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ning FL, Pei JP, Zhang NN, et al. Harvest of at least 18 lymph nodes is associated with improved survival in patients with pN0 colon cancer: a retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2020;146:2117–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Paggio JC, Peng Y, Wei X, et al. Population-based study to re-evaluate optimal lymph node yield in colonic cancer. Br J Surg 2017;104:1087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during the study process are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.