Abstract

Background

Cesarean section is a common surgical procedure that may be considered a safe alternative to natural birth and helps to resolve numerous obstetric conditions. Still, the Cesarean section is painful; relieving pain after a Cesarean section is crucial, therefore analgesia is necessary for the postoperative period. However, analgesia is not free of complications and contraindications, so massage may be a cost-effective method for decreasing pain post-Cesarean. Our study aims to determine the massage role in pain intensity after Cesarean sections.

Methods

We searched five electronic databases for relevant studies. Data were extracted from the included studies after screening procedures. We calculated the pooled mean difference (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD) for our continuous outcomes, using random or fixed-effect meta-analysis according to heterogenicity status. Interventional studies were assessed for methodological quality using the Cochrane risk-of-bias assessment tool, while observational studies were assessed using the National Institutes of Health’s tools.

Results

Our study included 10 RCTs and five observational studies conducted with over 1,595 post-Cesarean women. The pooled MDs for pain intensity considering baseline values either immediately or post 60–90 minutes were favoring the massagegroup over the control group as follows:(stand. MD = −2.64, 95% CI [−3.80, −1.48], p >.00001; MD = −2.64, 95% CI [−3.80, −1.48], p >.00001, respectively). While pooled MDsregarding post-intervention only eitherimmediately or post 60–90 minutes were:(stand. MD = −2.04, 95% CI [−3.26, −0.82], p =.001; stand. MD = −2.62, 95% CI [−3.52, −1.72],p > .00001, respectively).

Conclusion

Our study found that using massage was superior to the control groups in decreasing pain intensity either when the pain was assessed immediately after or 60–90 minutes post-massage application.

Keywords: massage, post-Cesarean, pain, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

A Cesarean section (CS) is a common surgical procedure to deliver a baby through incisions in the abdominal and uterine walls.(1) It is a safe alternative to natural birth and helps resolve obstetric conditions such as cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal malposition, and fetal distress, reducing maternal and neonatal mortality.(2)

After the surgery, the anesthetic effect wears off, and pain in the lower abdominal incision begins to emerge, usually within 24 hours.(3) Anesthesia can cause discomfort and psychological harm.(3) Pain is considered the fifth vital sign after body temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure.(4) Relieving incisional pain after a CS is crucial, so analgesia is necessary for post-operative recovery. The common methods of analgesia include epidural and intravenous analgesia, each with its drawbacks such as epidural catheter displacement and urine retention. (5)

Additionally, opioid analgesics are associated with respiratory depression, excessive sedation, nausea, vomiting, and other unpleasant responses.(5) Multimodal analgesia is increasingly used to improve the analgesic effect and reduce adverse reactions, but there is still room for improvement. Even with regular analgesics, pain management is inadequate in some cases.(3)

Massage is a low-cost, widely used alternative therapy that benefits various biological systems and promotes local and general circulation, immune function, natural healing, and homeostasis.(6) Local massage can also reduce pain by stimulating non-painful nerve fibers and interfering with pain transmission in the spinal cord.(6) Foot and hand massage has effectively reduced post-operative incision pain.(7) They are ideal locations for massage because they have many mechanoreceptors stimulating non-painful nerve fibers and reducing pain.(7)

Many studies have been published since the last meta-analysis, which discussed the effect of massage on decreasing pain after CS.(7–11) In our study, we aim mainly to assess the efficacy of massage on pain post-CS to determine its role in everyday practice. Additionally, we aim to include all massage types, not only hand and foot massage.

METHODS

The study was designed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and reported under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.(12,13)

Literature Search

We searched Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane CENTRAL, and EMBASE from inception until February 2023. Additionally, all references listed in all eligible articles and prior meta-analyses on the same topic were retrieved to identify any other missed relevant citations. The following search terms were used: (“Cesarean section” OR “abdominal Deliver*” OR “caesarean Section” OR cesarian OR cesarean OR “c-section” OR csection OR “c section” OR “surgical delivery” OR “surgical birth”) AND (massage OR massages OR “zone therapy” OR Qigong OR “Ch’i Kung” OR “Tui na”).

Eligibility Criteria

Two reviewers independently screened the retrieved references according to the eligibility criteria. The following criteria were applied to include the studies in our systematic review: 1) studies whose patients are post-CS females; 2) studies whose intervention was massage (any type); 3) studies in which the comparator or a control group did not receive any type of massage; 4) studies that assessed any of the following outcomes: pain (the primary outcome), systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate; and 5) any study design comparing massage versus control group. We excluded different studies for the following reasons: 1) animal studies; 2) studies that were not in English; 3) abstracts only; and 4) study data that were not published yet.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed using an offline data extraction sheet. The following data were extracted: study ID (first author and publication year), country, study design, age of participants, description of massage, the protocol for tacking additional pain killer, inclusion criteria, conclusions, and main outcomes, which were as follows: pain intensity, sleep quality, fatigue severity, Post-partum Comfort Questionnaire Anxiety, opioid and NSAID use, stress, relaxation, the effect of massage on abdominal pain, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, the effect of massage on breastfeeding, headache, need for breastfeeding support, breastfeeding success score, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and prevent urinary retention after Cesarean delivery.

Risk of Bias Evaluation

Two authors independently assessed observational studies for their methodological quality using the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) tool.(14) The authors’ opinion is classified as “good”, “fair”, or “poor” according to scores obtained during the assessment. As for RCTs, the quality of the included trials was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias assessment tool (ROB) for interventional studies.(15) This tool comprises the following parameters: selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other possible sources of bias. The authors’ judgment was categorized as “high”, “low”, and “unclear” risk of bias. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by a third assessor.

Data Synthesis

Our assessed outcomes were continuous and were pooled as mean differences (MDs) between the two groups with 95% CIs using the inverse variance method. When applicable, we calculated and pooled the change between before and after the massage or the control; otherwise, we analyzed the post-intervention only when the pre-intervention data were unavailable. We also used standardized MD when different scales were used to assess the same outcome. The fixed effects model was first applied if the effect estimate was pooled from homogenous studies; otherwise, the random effects model was applied. We investigated the statistical heterogeneity between studies using the I2 statistics chi-squared test, with p < .1 considered heterogeneous and I2 ≥ 50% suggestive of high heterogeneity. The Review Manager Software (RevMan) version 5.4 (London, UK; www.cochrane.org ) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Results of Literature Search

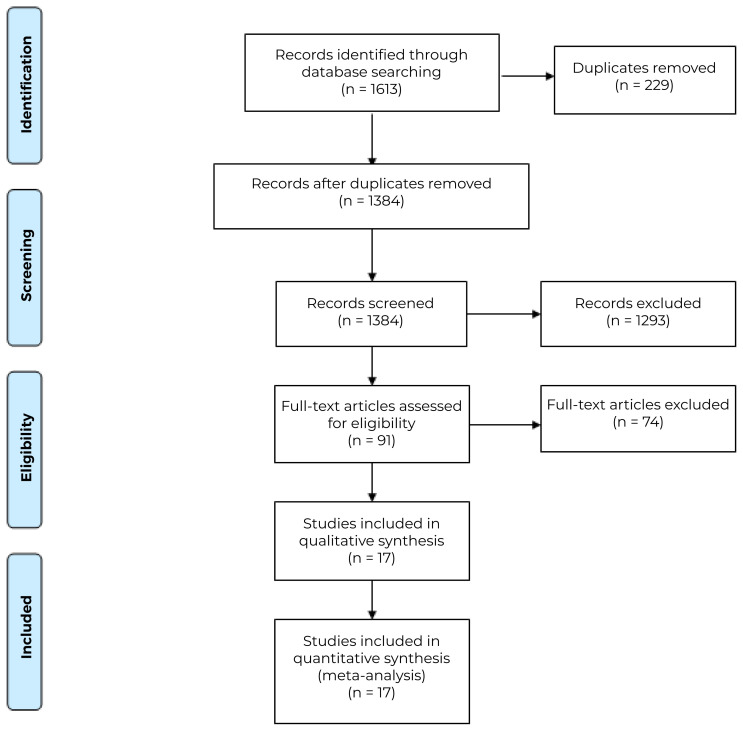

Our search method using four databases resulted in 1,363 studies. After duplicate elimination, 904 studies were eligible for screening. After title and abstract screening, 46 articles were found reliable for full-text screening. We rejected 31 of these; eventually, 10 articles met our criteria and were included in our meta-analysis, while five studies were only included as a systematic review.(8,9, 10,11,16–21,22–26) Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the study selection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart

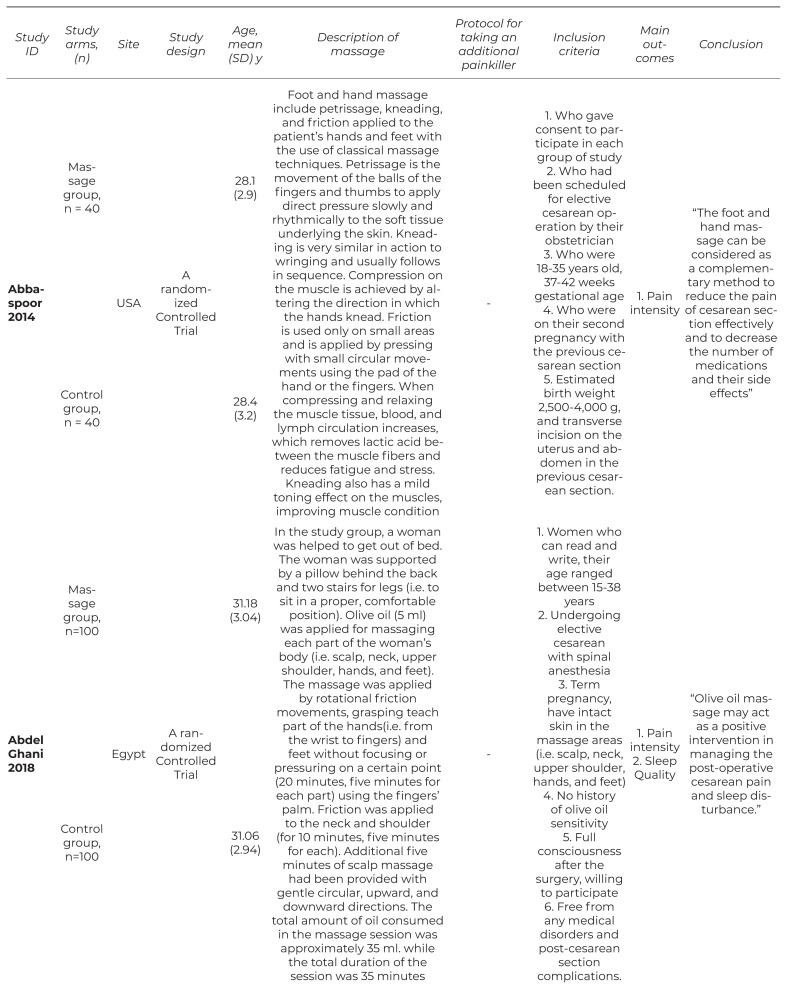

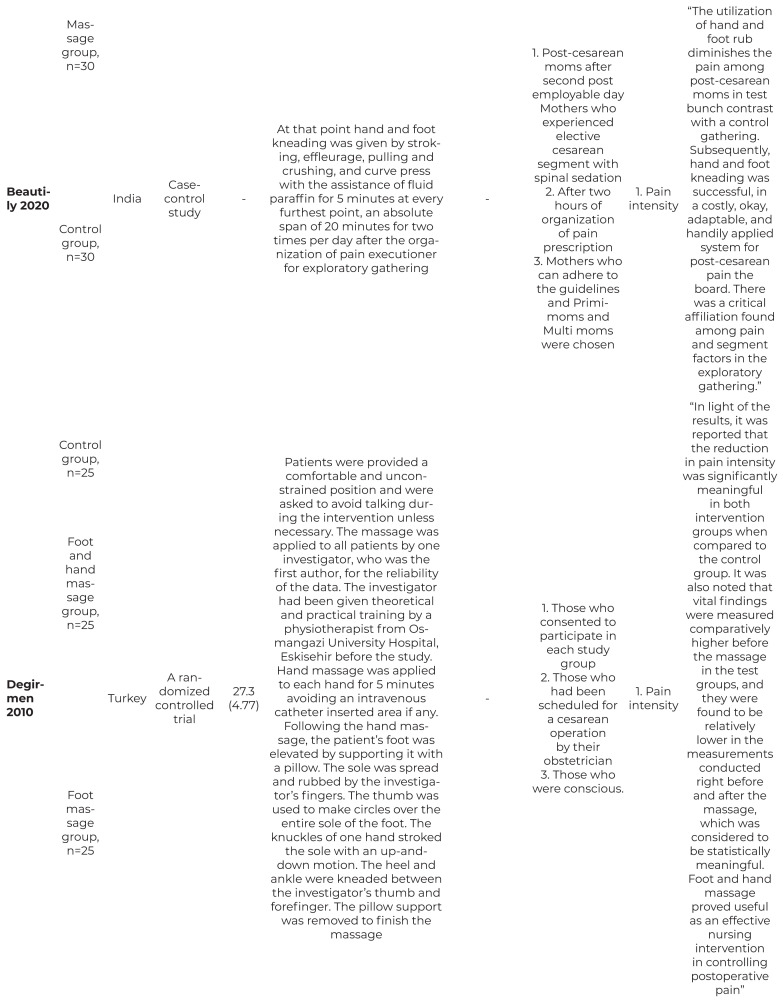

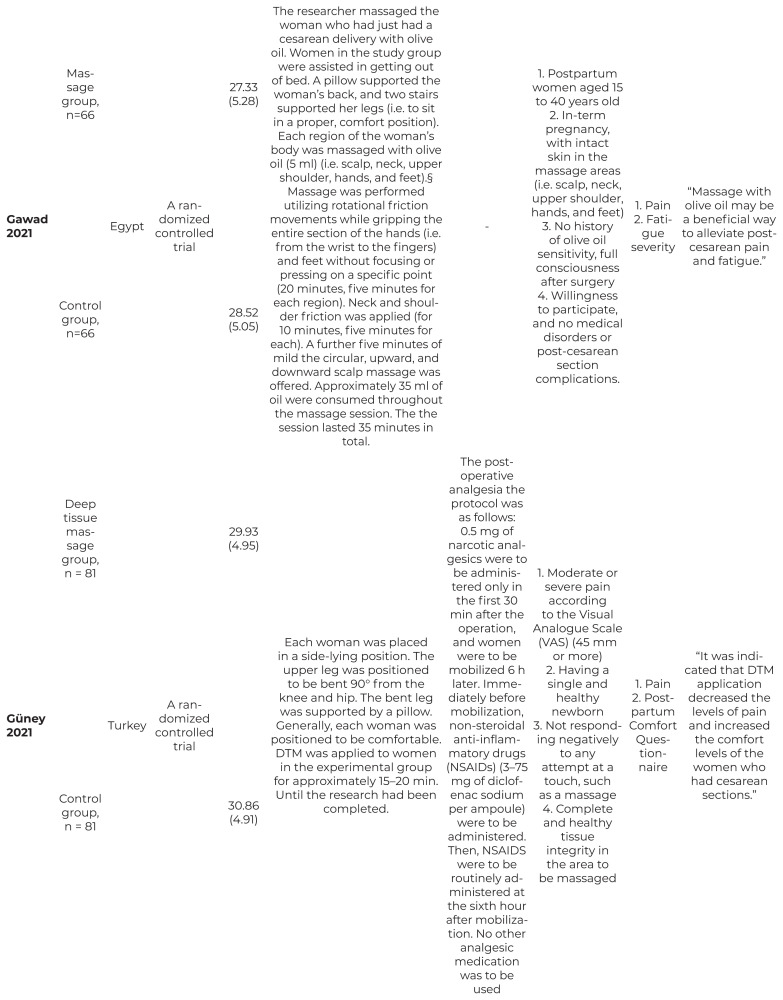

Study Characteristics

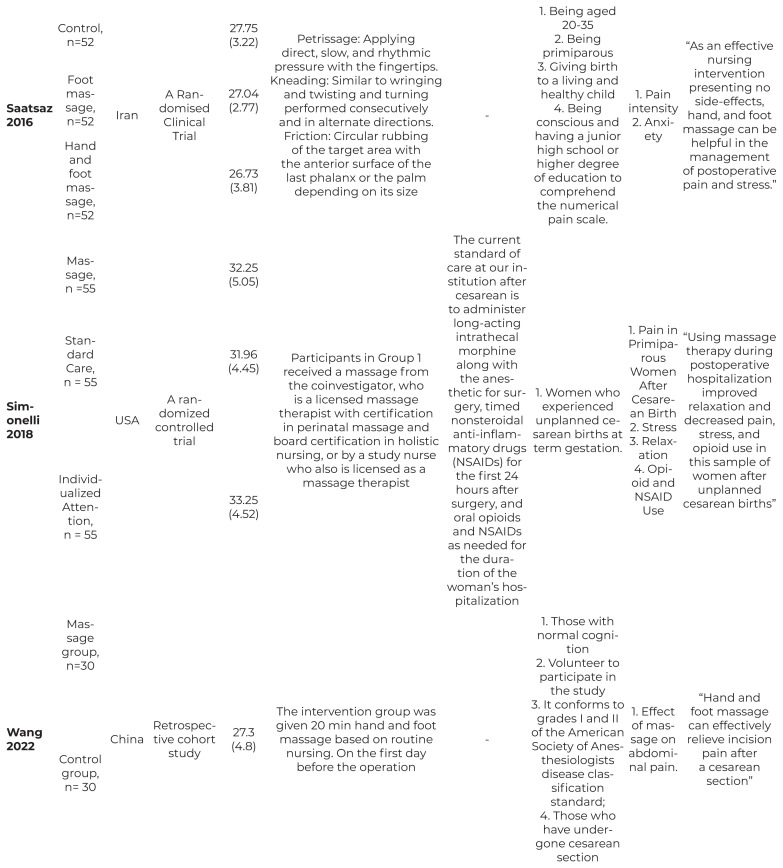

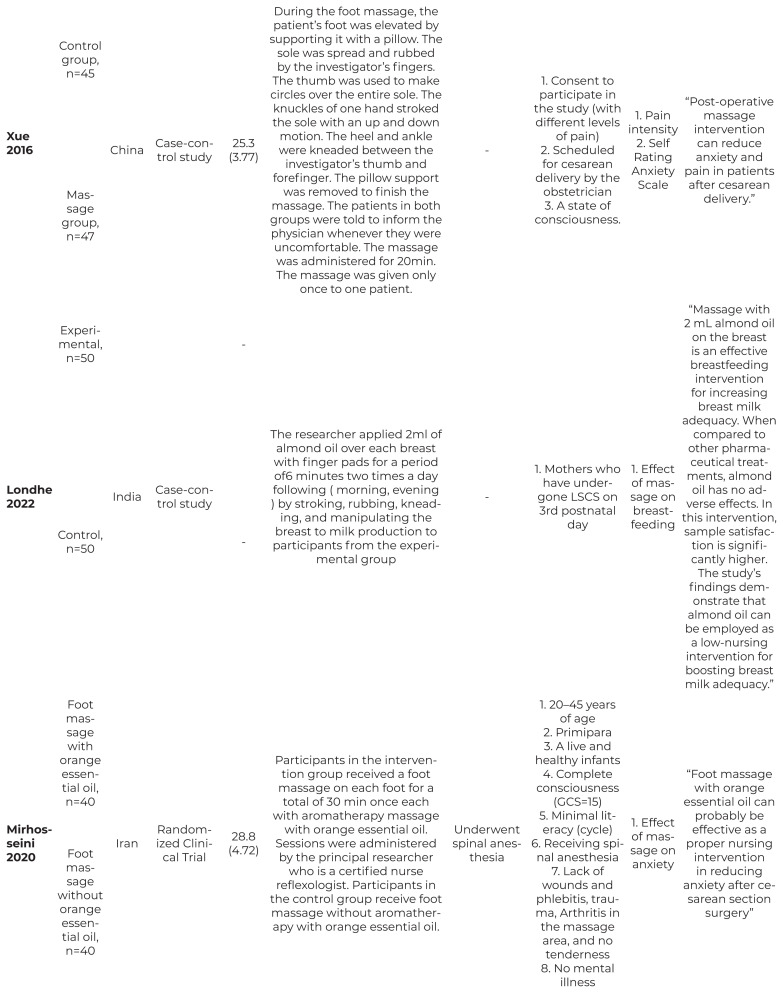

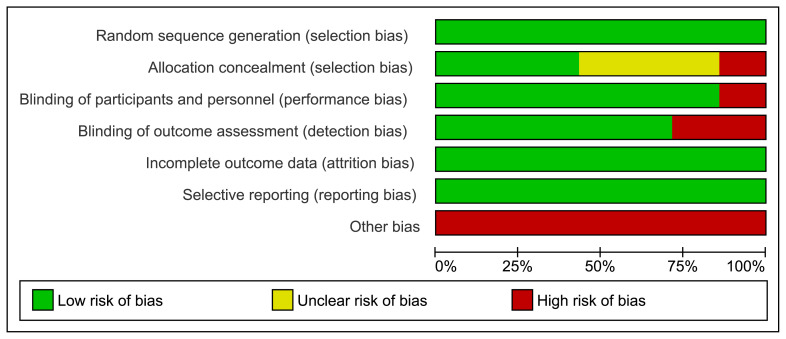

Our study included 10 RCTs and five observational studies conducted in six countries with over 1,595 post-CS women.(8,9,10,11,16,17–20,23,25) The main outcome in most of the studies was pain intensity. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics and summary of included studies.

Table 1.

Summary and Baseline Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Study ID | Study arms, (n) | Site | Study design | Age, mean (SD) y | Description of massage | Protocol for taking an additional painkiller | Inclusion criteria | Main outcomes | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbaspoor 2014 | Massage group, n = 40 | USA | A randomized Controlled Trial | 28.1 (2.9) | Foot and hand massage include petrissage, kneading, and friction applied to the patient’s hands and feet with the use of classical massage techniques. Petrissage is the movement of the balls of the fingers and thumbs to apply direct pressure slowly and rhythmically to the soft tissue underlying the skin. Kneading is very similar in action to wringing and usually follows in sequence. Compression on the muscle is achieved by altering the direction in which the hands knead. Friction is used only on small areas and is applied by pressing with small circular movements using the pad of the hand or the fingers. When compressing and relaxing the muscle tissue, blood, and lymph circulation increases, which removes lactic acid between the muscle fibers and reduces fatigue and stress. Kneading also has a mild toning effect on the muscles, improving muscle condition | - | 1. Who gave consent to participate in each group of study 2. Who had been scheduled for elective cesarean operation by their obstetrician 3. Who were 18–35 years old, 37–42 weeks gestational age 4. Who were on their second pregnancy with the previous cesarean section 5. Estimated birth weight 2,500–4,000 g, and transverse incision on the uterus and abdomen in the previous cesarean section. |

1. Pain intensity | “The foot and hand massage can be considered as a complementary method to reduce the pain of cesarean section effectively and to decrease the number of medications and their side effects” |

| Control group, n = 40 | 28.4 (3.2) | ||||||||

| Abdel Ghani 2018 | Massage group, n=100 | Egypt | A randomized Controlled Trial | 31.18 (3.04) | In the study group, a woman was helped to get out of bed. The woman was supported by a pillow behind the back and two stairs for legs (i.e. to sit in a proper, comfortable position). Olive oil (5 ml) was applied for massaging each part of the woman’s body (i.e. scalp, neck, upper shoulder, hands, and feet). The massage was applied by rotational friction movements, grasping teach part of the hands(i.e. from the wrist to fingers) and feet without focusing or pressuring on a certain point (20 minutes, five minutes for each part) using the fingers’ palm. Friction was applied to the neck and shoulder (for 10 minutes, five minutes for each). Additional five minutes of scalp massage had been provided with gentle circular, upward, and downward directions. The total amount of oil consumed in the massage session was approximately 35 ml. while the total duration of the session was 35 minutes | - | 1. Women who can read and write, their age ranged between 15–38 years 2. Undergoing elective cesarean with spinal anesthesia 3. Term pregnancy, have intact skin in the massage areas (i.e. scalp, neck, upper shoulder, hands, and feet) 4. No history of olive oil sensitivity 5. Full consciousness after the surgery, willing to participate 6. Free from any medical disorders and post-cesarean section complications. |

1. Pain intensity 2. Sleep Quality |

“Olive oil massage may act as a positive intervention in managing the post-operative cesarean pain and sleep disturbance.” |

| Control group, n=100 | 31.06 (2.94) | ||||||||

| Beautily 2020 | Massage group, n=30 | India | Case-control study | - | At that point hand and foot kneading was given by stroking, effleurage, pulling and crushing, and curve press with the assistance of fluid paraffin for 5 minutes at every furthest point, an absolute span of 20 minutes for two times per day after the organization of pain executioner for exploratory gathering | - | 1. Post-cesarean moms after second post employable day Mothers who experienced elective cesarean segment with spinal sedation 2. After two hours of organization of pain prescription 3. Mothers who can adhere to the guidelines and Primi-moms and Multi moms were chosen |

1. Pain intensity | “The utilization of hand and foot rub diminishes the pain among post-cesarean moms in test bunch contrast with a control gathering. Subsequently, hand and foot kneading was successful, in a costly, okay, adaptable, and handily applied system for post-cesarean pain the board. There was a critical affiliation found among pain and segment factors in the exploratory gathering.” |

| Control group, n=30 | |||||||||

| Degirmen 2010 | Control group, n=25 | Turkey | A randomized controlled trial | 27.3 (4.77) | Patients were provided a comfortable and unconstrained position and were asked to avoid talking during the intervention unless necessary. The massage was applied to all patients by one investigator, who was the first author, for the reliability of the data. The investigator had been given theoretical and practical training by a physiotherapist from Osmangazi University Hospital, Eskisehir before the study. Hand massage was applied to each hand for 5 minutes avoiding an intravenous catheter inserted area if any. Following the hand massage, the patient’s foot was elevated by supporting it with a pillow. The sole was spread and rubbed by the investigator’s fingers. The thumb was used to make circles over the entire sole of the foot. The knuckles of one hand stroked the sole with an up-and-down motion. The heel and ankle were kneaded between the investigator’s thumb and forefinger. The pillow support was removed to finish the massage | - | 1. Those who consented to participate in each study group 2. Those who had been scheduled for a cesarean operation by their obstetrician 3. Those who were conscious. |

1. Pain intensity | “In light of the results, it was reported that the reduction in pain intensity was significantly meaningful in both intervention groups when compared to the control group. It was also noted that vital findings were measured comparatively higher before the massage in the test groups, and they were found to be relatively lower in the measurements conducted right before and after the massage, which was considered to be statistically meaningful. Foot and hand massage proved useful as an effective nursing intervention in controlling postoperative pain” |

| Foot and hand massage group, n=25 | |||||||||

| Foot massage group, n=25 | |||||||||

| Gawad 2021 | Massage group, n=66 | Egypt | A randomized controlled trial | 27.33 (5.28) | The researcher massaged the woman who had just had a cesarean delivery with olive oil. Women in the study group were assisted in getting out of bed. A pillow supported the woman’s back, and two stairs supported her legs (i.e. to sit in a proper, comfort position). Each region of the woman’s body was massaged with olive oil (5 ml) (i.e. scalp, neck, upper shoulder, hands, and feet).§ Massage was performed utilizing rotational friction movements while gripping the entire section of the hands (i.e. from the wrist to the fingers) and feet without focusing or pressing on a specific point (20 minutes, five minutes for each region). Neck and shoulder friction was applied (for 10 minutes, five minutes for each). A further five minutes of mild the circular, upward, and downward scalp massage was offered. Approximately 35 ml of oil were consumed throughout the massage session. The the session lasted 35 minutes in total. | - | 1. Postpartum women aged 15 to 40 years old 2. In-term pregnancy, with intact skin in the massage areas (i.e. scalp, neck, upper shoulder, hands, and feet) 3. No history of olive oil sensitivity, full consciousness after surgery 4. Willingness to participate, and no medical disorders or post-cesarean section complications. |

1. Pain 2. Fatigue severity |

“Massage with olive oil may be a beneficial way to alleviate post-cesarean pain and fatigue.” |

| Control group, n=66 | 28.52 (5.05) | ||||||||

| Güney 2021 | Deep tissue massage group, n = 81 | Turkey | A randomized controlled trial | 29.93 (4.95) | Each woman was placed in a side-lying position. The upper leg was positioned to be bent 90° from the knee and hip. The bent leg was supported by a pillow. Generally, each woman was positioned to be comfortable. DTM was applied to women in the experimental group for approximately 15–20 min. Until the research had been completed. | The postoperative analgesia the protocol was as follows: 0.5 mg of narcotic analgesics were to be administered only in the first 30 min after the operation, and women were to be mobilized 6 h later. Immediately before mobilization, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (3–75 mg of diclofenac sodium per ampoule) were to be administered. Then, NSAIDS were to be routinely administered at the sixth hour after mobilization. No other analgesic medication was to be used | 1. Moderate or severe pain according to the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (45 mm or more) 2. Having a single and healthy newborn 3. Not responding negatively to any attempt at a touch, such as a massage 4. Complete and healthy tissue integrity in the area to be massaged |

1. Pain 2. Postpartum Comfort Questionnaire |

“It was indicated that DTM application decreased the levels of pain and increased the comfort levels of the women who had cesarean sections.” |

| Control group, n = 81 | 30.86 (4.91) | ||||||||

| Saatsaz 2016 | Control, n=52 | Iran | A Randomised Clinical Trial | 27.75 (3.22) | Petrissage: Applying direct, slow, and rhythmic pressure with the fingertips. Kneading: Similar to wringing and twisting and turning performed consecutively and in alternate directions. Friction: Circular rubbing of the target area with the anterior surface of the last phalanx or the palm depending on its size | - | 1. Being aged 20–35 2. Being primiparous 3. Giving birth to a living and healthy child 4. Being conscious and having a junior high school or higher degree of education to comprehend the numerical pain scale. |

1. Pain intensity 2. Anxiety | “As an effective nursing intervention presenting no side-effects, hand, and foot massage can be helpful in the management of postoperative pain and stress.” |

| Foot massage, n=52 | 27.04 (2.77) | ||||||||

| Hand and foot massage, n=52 | 26.73 (3.81) | ||||||||

| Simonelli 2018 | Massage, n =55 | USA | A randomized controlled trial | 32.25 (5.05) | Participants in Group 1 received a massage from the coinvestigator, who is a licensed massage therapist with certification in perinatal massage and board certification in holistic nursing, or by a study nurse who also is licensed as a massage therapist | The current standard of care at our institution after cesarean is to administer long-acting intrathecal morphine along with the anesthetic for surgery, timed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the first 24 hours after surgery, and oral opioids and NSAIDs as needed for the duration of the woman’s hospitalization | 1. Women who experienced unplanned cesarean births at term gestation. | 1. Pain in Primiparous Women After Cesarean Birth 2. Stress 3. Relaxation 4. Opioid and NSAID Use |

“Using massage therapy during postoperative hospitalization improved relaxation and decreased pain, stress, and opioid use in this sample of women after unplanned cesarean births” |

| Standard Care, n = 55 | 31.96 (4.45) | ||||||||

| Individualized Attention, n = 55 | 33.25 (4.52) | ||||||||

| Wang 2022 | Massage group, n=30 | China | Retrospective cohort study | 27.3 (4.8) | The intervention group was given 20 min hand and foot massage based on routine nursing. On the first day before the operation | - | 1. Those with normal cognition 2. Volunteer to participate in the study 3. It conforms to grades I and II of the American Society of Anesthesiologists disease classification standard; 4. Those who have undergone cesarean section |

1. Effect of massage on abdominal pain. | “Hand and foot massage can effectively relieve incision pain after a cesarean section” |

| Control group, n= 30 | |||||||||

| Xue 2016 | Control group, n=45 | China | Case-control study | 25.3 (3.77) | During the foot massage, the patient’s foot was elevated by supporting it with a pillow. The sole was spread and rubbed by the investigator’s fingers. The thumb was used to make circles over the entire sole. The knuckles of one hand stroked the sole with an up and down motion. The heel and ankle were kneaded between the investigator’s thumb and forefinger. The pillow support was removed to finish the massage. The patients in both groups were told to inform the physician whenever they were uncomfortable. The massage was administered for 20min. The massage was given only once to one patient. | - | 1. Consent to participate in the study (with different levels of pain) 2. Scheduled for cesarean delivery by the obstetrician 3. A state of consciousness. |

1. Pain intensity 2. Self Rating Anxiety Scale |

“Post-operative massage intervention can reduce anxiety and pain in patients after cesarean delivery.” |

| Massage group, n=47 | |||||||||

| Londhe 2022 | Experimental, n=50 | India | Case-control study | - | The researcher applied 2ml of almond oil over each breast with finger pads for a period of6 minutes two times a day following ( morning, evening ) by stroking, rubbing, kneading, and manipulating the breast to milk production to participants from the experimental group | - | 1. Mothers who have undergone LSCS on 3rd postnatal day | 1. Effect of massage on breastfeeding | “Massage with 2 mL almond oil on the breast is an effective breastfeeding intervention for increasing breast milk adequacy. When compared to other pharmaceutical treatments, almond oil has no adverse effects. In this intervention, sample satisfaction is significantly higher. The study’s findings demonstrate that almond oil can be employed as a low-nursing intervention for boosting breast milk adequacy.” |

| Control, n=50 | - | ||||||||

| Mirhosseini 2020 | Foot massage with orange essential oil, n=40 | Iran | Randomized Clinical Trial | 28.8 (4.72) | Participants in the intervention group received a foot massage on each foot for a total of 30 min once each with aromatherapy massage with orange essential oil. Sessions were administered by the principal researcher who is a certified nurse reflexologist. Participants in the control group receive foot massage without aromatherapy with orange essential oil. | Underwent spinal anesthesia | 1. 20–45 years of age 2. Primipara 3. A live and healthy infants 4. Complete consciousness (GCS=15) 5. Minimal literacy (cycle) 6. Receiving spinal anesthesia 7. Lack of wounds and phlebitis, trauma, Arthritis in the massage area, and no tenderness 8. No mental illness |

1. Effect of massage on anxiety | “Foot massage with orange essential oil can probably be effective as a proper nursing intervention in reducing anxiety after cesarean section surgery” |

| Foot massage without orange essential oil, n=40 | |||||||||

| Rasooli 2019 | Hand massage group, n=20 | Iran | Randomized Clinical Trial | 27.45 (5.32) | The massage was used 3 times per day for 15 minutes at hours of 11.30, 16.30, and 20.30 on the pressure points of the hands (Zhong Zhu, Yang Chi, Thai Ling, Shen Men) | underwent cesarean section using spinal anesthesia | 1. Women aged between 18 and 40 years 2. Who underwent cesarean section using spinal anesthesia 3. The same anesthesiologist (For all patients) 4. Lack of visual impairment, and having the reading/writing literacy |

1. Effect of massage on headache | “Findings of this research suggest that massage therapy affects the severity of headache caused by spinal anesthesia in patients underwent cesarean section surgery” |

| Head-neck massage group, n=20 | 26.85 (5.44) | The massage was used 3 times per day for 15 minutes during 2 consecutive days on the pressure points of head and neck (Masseter, Trapezius Sternomastoid, and Temporalis) | |||||||

| Control group, n=20 | 27.8 (7) | - | |||||||

| Shahri 2021 | Massage group, n=55 | Iran | Randomized Clinical Trial | 29.85 (4.43) | Oketani breast massage was performed using eight different manual techniques. Steps 1 to 7 are called “course of treatment” and Step 8, “expressing or milking”. A set of operations and expressing are completed within one minute and this is repeated for 15 to 20 minutes. | - | 1. Mothers aged between 18 to 35 years 2. Singleton pregnancy 3. Absence of physical and mental illness that prevented breastfeeding based on the available medical records 4. Gestational age of 38 to 42 weeks 5. No history of breast surgery and breast tumor 6. The absence of disorders such as placental abruption, placenta previa, heart, and respiratory diseases during pregnancy 7. Lack of hepatitis and AIDS during pregnancy and afterward 8. The birth of a healthy and mature baby weighing more than 2500 grams 9. The first- and fifth-minute Apgar a score of above 7 10. The absence of the need for any postnatal medical intervention based on the medical records and the absence of any cleft palate and cleft lip in the infant. |

1. Effect of massage on breastfeeding 2. Need for breastfeeding support (LATCH) 3. Breastfeeding success score (IBFAT) 4. Breastfeeding self-efficacy (BSES) |

“Oketani massage can be used as a care intervention by nurses to improve breastfeeding in mothers who undergo cesarean sections.” |

| Control group, n=58 | 28.95 (5.33) | ||||||||

| Dal 2013 | Intervention group 1, n=20 | Turkey | Cross-sectional study | 29.7 (5.8) | The first intervention group consisted of women who were given effleurage and friction massages for 10–15 min by the researcher each hour after completion of the cesarean section. The second intervention group consisted of women who were given effleurage and friction massages after cesarean section for 10–15 min every 30 min after they reported having a voiding sensation. Routine clinical services (having women listen to the sound of water, provide a bedpan, emptying the urinary bladder with a urinary catheter when needed) were provided for the control group in cases of difficulty in voiding | - | 1. Patients who had undergone cesarean delivery 2. Who did not have urinary or neurological problems 3. Who was able to verbally communicate 4. Who had volunteered to participate in this study 5. Who had not had urinary catheters inserted 6. Who had not experienced contraindications for massage were included in the study |

1. Prevent urinary retention after cesarian delivery | “To facilitate voiding and prevent urinary retention, which is seen as a post-cesarean complication, massaging the sacral region could be recommended instead of urinary catheter insertion.” |

| Intervention group 2, n=20 | 31.8 (5.8) | ||||||||

| Control group, n=20 | 30.9 (6.1) |

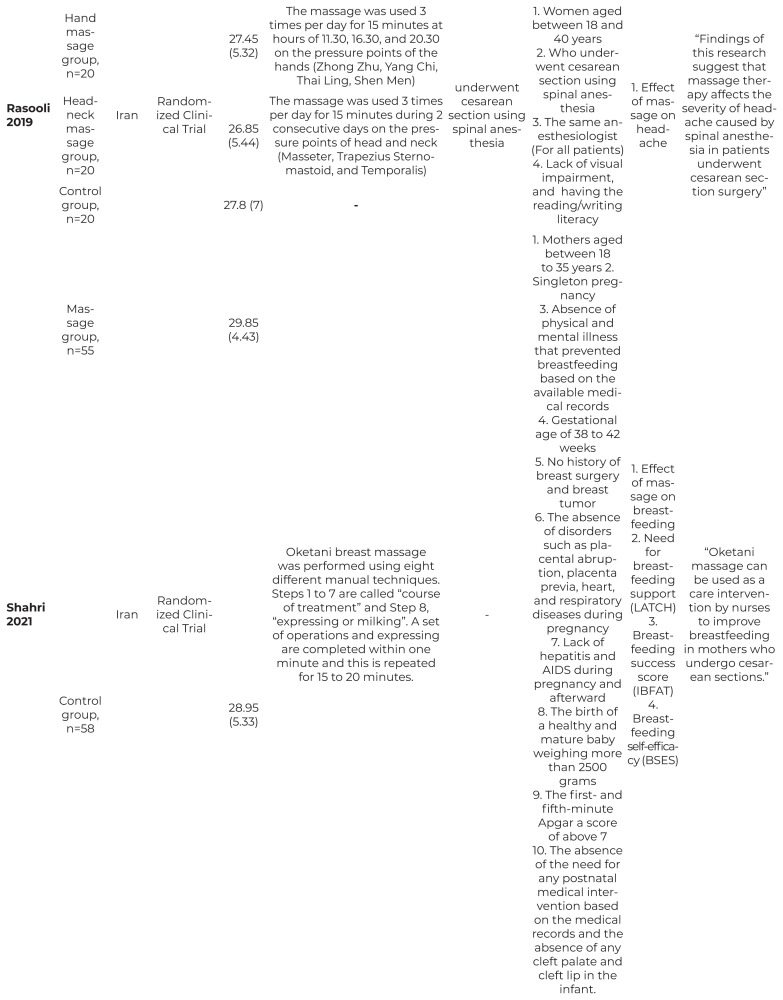

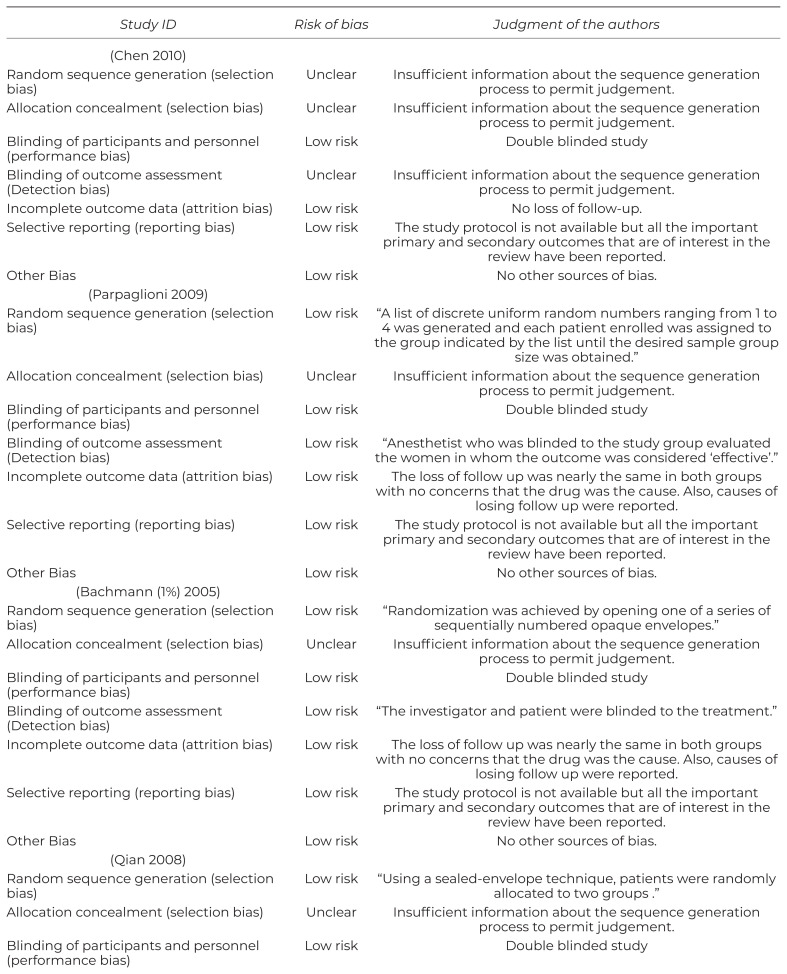

Risk of Bias Assessment

According to the NIH tool, observational studies showed a fair risk of bias. As for trials, the overall authors’ judgment was high to moderate quality according to the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. Although all of the trials showed a low risk of bias regarding random sequence generation (except Abdel-Ghani et al.(16) which did not declare their randomization status), blinding in most of them was unclear, and it is considered here a key domain for potential bias. Figure 2 shows the summary of the risk of bias in interventional trials, while the summary of observational studies is shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph summary for RCTs

Table 2.

Quality assessment of RCTs by Cochrane tool

| Study ID | Risk of bias | Judgment of the authors |

|---|---|---|

| (Chen 2010) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No loss of follow-up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

| (Parpaglioni 2009) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “A list of discrete uniform random numbers ranging from 1 to 4 was generated and each patient enrolled was assigned to the group indicated by the list until the desired sample group size was obtained.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Low risk | “Anesthetist who was blinded to the study group evaluated the women in whom the outcome was considered ‘effective’.” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The loss of follow up was nearly the same in both groups with no concerns that the drug was the cause. Also, causes of losing follow up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

| (Bachmann (1%) 2005) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomization was achieved by opening one of a series of sequentially numbered opaque envelopes.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Low risk | “The investigator and patient were blinded to the treatment.” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The loss of follow up was nearly the same in both groups with no concerns that the drug was the cause. Also, causes of losing follow up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

| (Qian 2008) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Using a sealed-envelope technique, patients were randomly allocated to two groups.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Low risk | “Patients were assessed and cared for, and the study data recorded by a blinded researcher.” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The loss of follow up was nearly the same in both groups with no concerns that the drug was the cause. Also, causes of losing follow up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

| (Bachmann (0.75%) 2005) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The loss of follow up was nearly the same in both groups with no concerns that the drug was the cause. Also, causes of losing follow up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

| (Chen 2021) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Not reported but the study seemed to be noon-blinded (an open label study). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The loss of follow up was nearly the same in both groups with no concerns that the drug was the cause. Also, causes of losing follow up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

| (Miao 2021) | ||

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Patients were randomized to the receipt of a continuous epidural infusion with PCEA of one of the four solutions using the sealed-envelope technique.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double blinded study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Low risk | “A blinded observer evaluated the patients.” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The loss of follow up was nearly the same in both groups with no concerns that the drug was the cause. Also, causes of losing follow up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but all the important primary and secondary outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported. |

| Other Bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias. |

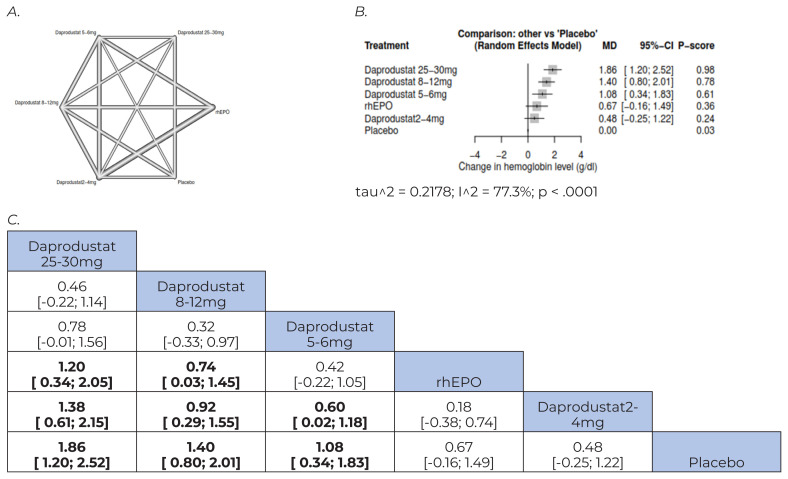

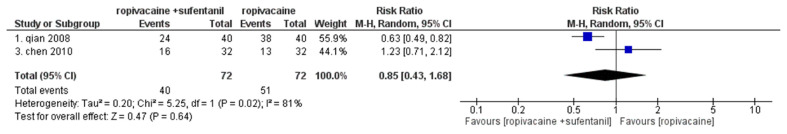

Primary Outcomes

Pain intensity assessed right after massage

Pain intensity pre and post-massage were reported in six studies with 688 patients included.(9,11,16,18,19,21) The pooled standardized MD showed a significant difference, favoring the massage group (stand. MD = −2.64, 95% CI [−3.80, −1.48], p > .00001). The pooled studies were heterogenous (χ2 p > .00001, I2 = 97%); however, we could not resolve heterogenicity by the sensitivity analyses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of change in pain intensity between pre and post-massage (assessed right after massage)

Pain intensity post-massage only was reported in seven studies with 798 patients included.(8–11,16,18,19) The pooled standardized MD showed a significant difference, favoring the massage group (stand. MD = −2.04, 95% CI [−3.26, −0.82], p = .001). The pooled studies were heterogenous (χ2 p > .00001, I2 = 98%); we could not resolve heterogenicity by the sensitivity analyses (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of pain intensity post-massage only (assessed right after massage)

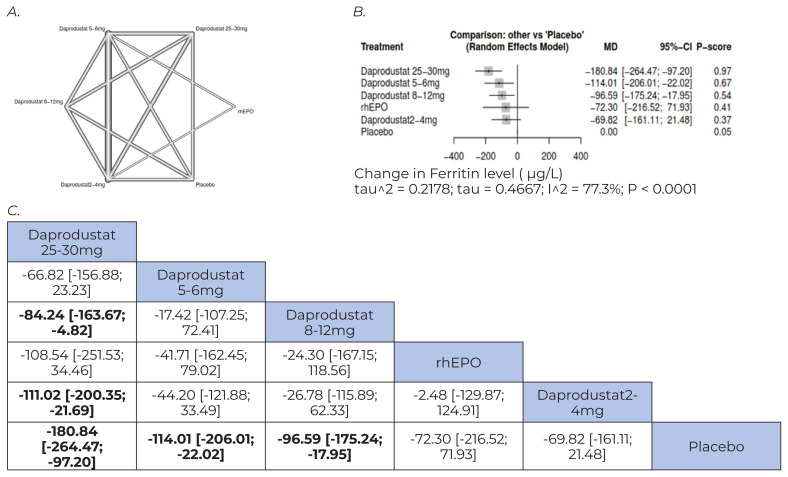

Pain intensity assessed 60–90 minutes after massage

Pain intensity pre- and post-60–90 minutes after massage was reported in six studies with 518 patients included.(9,11,17–20) The pooled MD favored the massage group over the control (MD = −2.50, 95% CI [−2.73, −2.27], p > .00001). The pooled studies were homogenous (χ2 p = .60, I2 = 0%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of change in pain intensity between pre and post-massage (assessed 60–90 minutes after massage)

Pain intensity post-60–90 minutes after massage only was reported in six studies with 518 patients included. (9,11,17–20) The pooled standardized MD showed a significant difference in favor of the massage group (stand. MD = −2.62, 95% CI [−3.52, −1.72], p > .00001). The pooled studies were heterogenous (χ2 p > .00001, I2 = 93%); nevertheless, we could not resolve heterogenicity by any means of sensitivity analyses (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of pain intensity post-massage only (assessed 60–90 minutes after massage)

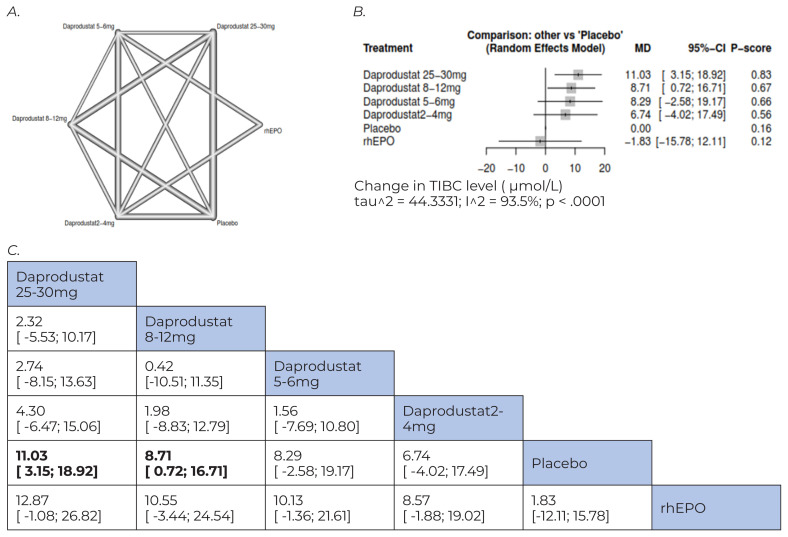

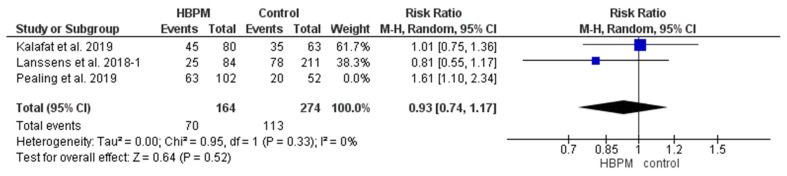

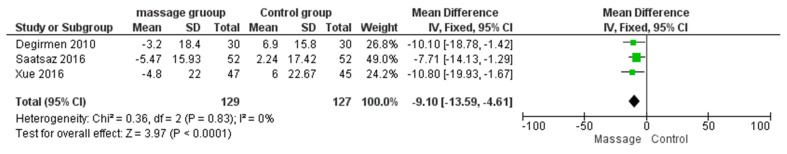

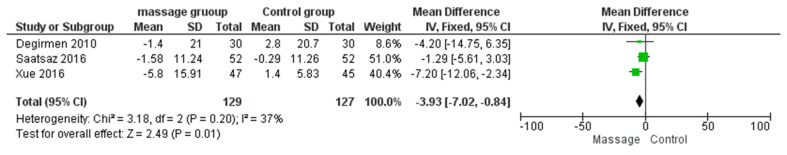

Secondary Outcomes

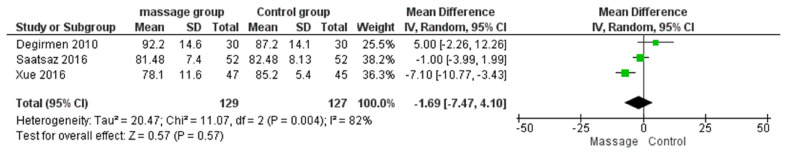

Change of systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate from the baseline was assessed after 60–90 minutes of massage in three studies with 256 patients included; the pooled MDs showed significant difference (p > .05) favoring the massage group, as follows: (MD = −9.10, −7.25, −3.93, and −2.21, respectively) (Figures 7–10).

Figure 7.

Change of systolic blood pressure from the baseline was assessed after 60–90 minutes of massage

Figure 8.

Forest plot of change of diastolic blood pressure from the baseline was assessed after 60–90 minutes of massage

Figure 9.

Forest plot of change of pulse from the baseline was assessed after 60–90 minutes of massage

Figure 10.

Forest plot of change of respiratory rate from the baseline was assessed after 60–90 minutes of massage

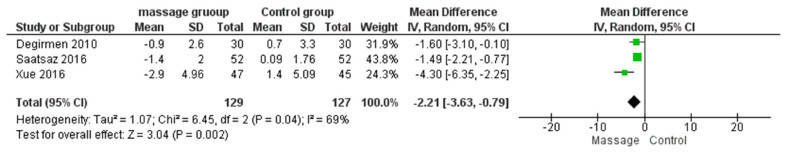

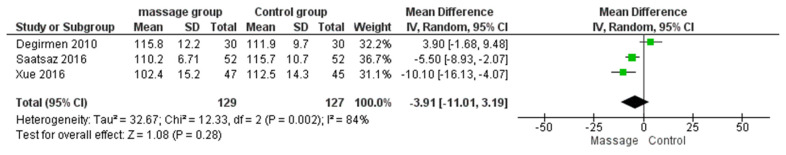

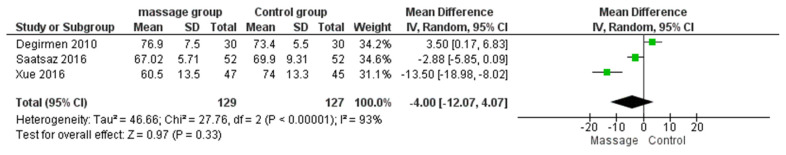

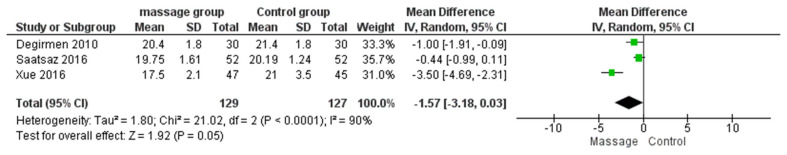

Additionally, we analyzed the latter secondary outcomes regarding post-massage values only, and the pooled MDs were as follows: (−3.91, −4.00, −1.69, and −1.57, respectively). They all showed significantly different outcomes towards massage groups, except for respiratory rate (Figures 11–14).

Figure 11.

Forest plot of systolic blood pressure that was assessed post-massage only

Figure 12.

Forest plot of diastolic blood pressure that was assessed post-massage only

Figure 13.

Forest plot of pulse that was assessed post-massage only

Figure 14.

Forest plot of the respiratory rate that was assessed post-massage only

DISCUSSION

Our study included 15 studies; 10 RCTs and five observational studies with 1,595 post-CS women who underwent different types and sites of massages. We excluded different populations as dialysis patients, which led to homogeneity of the population. Only 10 of our included studies were included in the quantitative analysis. The main outcome of our study is pain intensity. All of our pooled results showed significant improvement in the massage over the control groups regarding decreasing pain post-CS, whether the assessment was immediately after the massage or 60–90 minutes post-massage.

Our findings could be justified by the holistic nature of that massage therapy that incorporates several theories, such as the meridian theory, modern pathophysiology, bio-holographic embryo theory, and the reflection theory.(27,28) Suppose we applied some of these theories to Cesarean delivery as an example. In that case, the blood after the procedure is mainly outside the veins and remains in the skin, causing stagnation, blood stasis, and obstructed channels, which result in pain according to traditional Chinese medicine.(27,28) Massage can help promote blood circulation, clear the meridians, and alleviate pain. Pain receptors are found primarily in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with a high concentration in the hands and feet.(27,28) These receptors are mechanically stimulated and send signals to the brain through the spinal cord, which excites the vagus nerve influencing the hypothalamus.(27,28) This leads to an increase use of painkillers, such as enkephalins and dynorphins, and a decrease in pain-causing substances, which affects the secretion and metabolism of pain-related neurotransmitters and hormones, resulting in an analgesic effect.(27,28) Furthermore, massage therapy provides relaxation for the patient, allowing them to focus on the sensations caused by the massage and reducing pain by distracting their attention from it.(11,27,28)

Zimpel et al., in their recent meta-analysis, compared many complementariness and alternative therapies for post-CS pain, including hand and foot massage, and they were in line with our results regarding the efficacy of massage in decreasing pain.(29) Still, many studies were conducted afterward that were not included in their study.(8–11,23) They also were restricted in their analysis on hand foot massage, unlike our study, which comprised different types of massages. Furthermore, they did not standardize their MD, although their included studies used different scales to assess pain intensity.

Our study included all types of massage—foot and hand, all-body, deep-tissue, and massage with olive oil—in the analysis, trying to declare its role in decreasing pain and consequently improving the quality of life of women post-CS. Several studies have come to the same conclusions as ours, reinforcing our results; for example, researchers who utilized olive oil for post-Cesarean section massages showed a statistically significant difference between the study group and the control group.(9,16) Additionally, Pruyadarsini demonstrated a significant difference between the pre-and post-test results. Over half of the women studied had a severe pain level in the pre-test, but after receiving an olive oil massage, this pain level decreased to zero in the post-test.(30)

A qualitative study was conducted to investigate the impact of therapeutic massage therapy on pain levels after obstetric surgery. During the study, therapeutic massage was administered to the patient’s head, neck, shoulder, and back. The patients reported decreased pain levels at the end of the study.(31) These results, along with those of Güney et al., demonstrated that massage treatments in general, and deep tissue massage specifically, can effectively reduce pain levels among various patient groups.(10)

Additionally, our findings could be supported by other studies that did not target post-CS women but assessed the effect of massage on pain. A randomized controlled trial was conducted on participants with chronic low back pain; deep-tissue massage was just as effective as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.(32) In a case study of a pregnant woman, deep-tissue massage was used to alleviate low back pain and improve functional capacity. The study reported that massage therapy was associated with a reduction in low back pain and an improvement in functional capacity.(33) All the massage therapies discussed earlier are believed to improve circulation and lymphatic flow, which could potentially quicken the elimination of metabolic waste products and reduce fatigue.(34)

Our study had some limitations. 1) The assessment of the main outcome in the study is subjective, and this may make the same outcome varies, so we suggest coming studies choose another objective method to assess the efficacy of massage in decreasing pain as trying to measure the level of endogenous endorphins before and after massage or link between massage and the levels of inflammatory mediators. 2) The duration of massage varies across the studies, so it needs to be more stratification in further analyses when become available with sufficient data. 3) Also, in our study, we could not consider the analgesia in our analysis, and this is a major confounder that may affect the results, so future studies should stratify analgesia in their analyses with massage to exclude the confounding bias that may result from analgesia. 4) There was heterogenicity between the pooled studies and this may be mainly to different scales used, different study designs and the type of analgesia used among participants. 5) Lack of data sufficient for subgroup analysis according to the type of massage. 6) There were not enough studies available with longer follow-up durations to consider the true effectiveness of massage therapy not influenced by the negative effects of massage therapy as it is common that the patient may feel muscle soreness at the following day, lasting for two to four days as a result of the massage treatment itself, especially if the pressure was deep. 7) We found only one paper on the prevention of urinary retention after Cesarian section which wasn’t considered a clear indicator of the effectiveness of massage therapy. So, future studies should be done to prove this point.

Despite these previous limitations, we included all relevant published studies in the literature and all types of massage (all-body, hand and foot, deep-tissue, with olive oil) in our analyses. We also do subgroups according to the time of pain assessment post-massage, either immediately or 60–90 minutes post-massage, and we consider the change in MD from baseline whenever it was applicable in the analysis. Also, we limited our study to post-CS women to make the population as homogenous as possible.

CONCLUSION

In our study, we tried to clarify the role of massage on pain intensity in post-CS women. Our results favored massage over the control in decreasing post-CS pain immediately after the massage or 60–90 minutes post-massage application. We recommend further studies to stratify confounding associated with assessment and standardize measuring tools across studies, and the use of more objective tools to detect the role of massage in pain post-CS to build stronger evidence that could be generalized to improve everyday health practice and post-partum period management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships with other individuals or organizations that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, their work.

FUNDING

This study was not funded by any public, commercial, or non-profit organizations. The authors received no financial support or grants for the completion of this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venturella R, Quaresima P, Micieli M, Rania E, Palumbo A, Visconti F, et al. Non-obstetrical indications for cesarean section: a state-of-the-art review Arch Gynecol Obstetr 2018. Jul2981:9–16. 10.1007/s00404-018-4742-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Athiel Y, Girault A, Le Ray C, Goffinet F. Association between hospitals’ cesarean delivery rates for breech presentation and their success rates for external cephalic version. Eur J Obstetr Gynecol Repro Biol. 2022 Mar;270:156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greer A, Ramos L, Dubin J, Ramasamy R.118: Effect of limiting narcotic prescription on pain control following ambulatory scrotal surgery [conference abstract] J Sexual Med 2020. Jan17Suppl 1: S30–S31. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.11.064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers MP, Kuo PC.Pain as the fifth vital sign J Am Coll Surg 2020. Nov2315:601–602. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.07.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong M, Li X, Shen J, Ye M, Xiang H, Ma D.The effectiveness of preemptive analgesia for relieving postoperative pain after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS): a prospective, non-randomized controlled trial J Thorac Dis 2020. Sep129:4930–4940. 10.21037/jtd-20-2500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson NL.Massage therapy: understanding the mechanisms of action on blood pressure. A scoping review J Am Soc Hyperten 2015. Oct910: 785–793. 10.1016/j.jash.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimpel SA, Torloni MR, Porfirio G, da Silva EM. Complementary and alternative therapies for post-caesarean pain. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2014 Jul 24; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beautily V, Sharmila R.Adequacy of hand and foot massage on post cesarean pain among postnatal mothers Int J Res Pharmaceut Sci 202011SPL4:12–15. 10.26452/ijrps.v11iSPL4.3727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gawad S, Hassan M.Effect of Olive Oil Massage on the Severity of Post-Cesarean Pain and Fatigue Assiut Sci Nurs J 2021926:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Güney E, Uçar T.Effects of deep tissue massage on pain and comfort after cesarean: a randomized controlled trial Complement Ther Clin Pract 202143101320. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YQ, Jiang R, Pan J. Effect of foot and hand massage on abdominal pain of cesarean section incision under ultrasound guidance. Scanning. 2022 Jul;2022:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2022/8356256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar;:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd edition. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute. Study Assessment Tools. Bethesda, MD: NHLBI; 2021. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials [Internet] BMJ. 2019 Aug;:366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Ghani RM, Elmonem AS.Effect of olive oil massage on postoperative cesarean pain and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial IOSR J Nurs Health Sci 201872:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue M, Fan L, Ge LN, Zhang Y, Ge JL, Gu J, et al. Postoperative foot massage for patients after caesarean delivery Zeitschrift fur Geburtshilfe und Neonatologie 20162204:173–178. 10.1055/s-0042-104802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbaspoor Z, Akbari M, Najar S.Effect of foot and hand massage in post-cesarean section pain control: a randomized control trial Pain Manage Nurs 2014151:132–136. 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saatsaz S, Rezaei R, Alipour A, Beheshti Z. Massage as adjuvant therapy in the management of post-cesarean pain and anxiety: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;24:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degirmen N, Ozerdogan N, Sayiner D, Kosgeroglu N, Ayranci U.Effectiveness of foot and hand massage in postcesarean pain control in a group of Turkish pregnant women Appl Nurs Res 2010233:153–158. 10.1016/j.apnr.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simonelli MC, Doyle LT, Columbia MA, Wells PD, Benson KV, Lee CS.Effects of connective tissue massage on pain in primiparous women after cesarean birth J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2018475:591–601. 10.1016/j.jogn.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasooli AS, Atashkhoei S, Ghahramanian A, Goljaryan S, Zarie L.The effect of head-neck and hand massage on spinal headache after cesarean section: randomized clinical trial J Res Med Dent Sci 201862:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahdizadeh-Shahri M, Nourian M, Varzeshnejad M, Nasiri M.The effect of oketani breast massage on successful breastfeeding, mothers’ need for breastfeeding support, and breastfeeding self-efficacy: an experimental study Int J Therapeut Massage Bodywork 2021143:4–14. 10.3822/ijtmb.v14i3.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ümram DA, Korucu AE, Eroĝlu K, Karataş B, Yalçin A.Sacral region massage as an alternative to the urinary catheter used to prevent urinary retention after cesarean delivery Balkan Med J 2013301: 58–63. 10.5152/balkanmedj.2012.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Londhe NP, Bhore NR.Effectiveness of almond oil massage on breast feeding adequacy amongpostnatal mothers who are undergone LSCS from selected hospitals J Pharmaceut Negative Results 2022138:1181–1185. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirhosseini S, Abbasi A, Norouzi N, Mobaraki F, Basirinezhad MH, Mohammadpourhodki R.Effect of aromatherapy massage by orange essential oil on post-cesarean anxiety: a randomized clinical trial J Complement Integrat Med 2021183:579–583. 10.1515/jcim-2020-0138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu C, Lin M, Rauf HL, Shareef SS.Parameter simulation of multidimensional urban landscape design based on nonlinear theory Nonlinear Eng 2021. Jan101:583–591. 10.1515/nleng-2021-0049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou W, Gao B. Innovation and exploration of computer-aided new media translation course teaching mode under the ecological environment. J Environment Public Health. 2022 Oct;2022:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2022/6305590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Zimpel SA, Torloni MR, Porfírio GJ, Flumignan RL, da Silva EM.Complementary and alternative therapies for post-caesarean pain Cochrane Database System Rev 20209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruyadarsin IR. Effectiveness of olive oil massage on post caesarean pain and quality of sleep among primigravida mothers. Int J Pharmaceut Res. 2021;13(1) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams R, White B, Beckett C.The effects of massage therapy on pain management in the acute care setting Int J Therapeut Massage Bodywork 2010. Mar31:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majchrzycki M, Kocur P, Kotwicki T. Deep tissue massage and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a prospective randomized trial. Sci World J. 2014;2014:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/287597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romanowski MW, Spiritovic M.Deep tissue massage and its effect on low back pain and functional capacity of pregnant women—a case study J Novel Physiother 20160603. 10.4172/2165-7025.1000295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunes GS, Bender PU, de Menezes FS, Yamashitafuji I, Vargas VZ, Wageck B.Massage therapy decreases pain and perceived fatigue after long-distance Ironman triathlon: a randomised trial J Physiother 2016. Apr622:83–87. 10.1016/j.jphys.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]