Abstract

The viral replication factors E1 and E2 of papillomaviruses are necessary and sufficient to replicate plasmids containing the minimal origin of DNA replication in transient assays. Under physiological conditions, the upstream regulatory region (URR) governs expression of the early viral genes. To determine the effect of URR elements on E1 and E2 expression specifically, and on the regulation of DNA replication during the various phases of the viral life cycle, we carried out a systematic replication study with entire genomes of human papillomavirus type 31 (HPV31), a high-risk oncogenic type. We constructed a series of URR deletions, spacer replacements, and point mutations to analyze the role of the keratinocyte enhancer (KE) element, the auxiliary enhancer (AE) domain, and the L1-proximal end of the URR (5′-URR domain) in DNA replication during establishment, maintenance, and vegetative viral DNA amplification. Using transient and stable replication assays, we demonstrate that the KE and AE are necessary for efficient E1 and E2 gene expression and that the KE can also directly modulate viral replication. KE-mediated activation of replication is dependent on the position and orientation of the element. Mutation of either one of the four Ap1 sites, the single Sp1 site, or the binding site for the uncharacterized footprint factor 1 reduced replication efficiency through decreased expression of E1 and E2. Furthermore, the 5′-URR domain and the Oct1 DNA binding site are dispensable for viral replication, since such HPV31 mutants are able to replicate efficiently in a transient assay, maintain a stable copy number over several cell generations, and amplify viral DNA under vegetative conditions. Interestingly, deletion of the 5′-URR domain leads to increased transient and stable replication levels. These findings suggest that elements in the HPV31 URR outside the minimal origin modulate viral replication through both direct and indirect mechanisms.

Papillomaviruses are small viruses that contain circular, double-stranded DNA genomes of about 8,000 bp and infect the cutaneous or mucosal epithelium. More than 70 types of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) have been identified to date. These viral genomes have a common genetic and functional organization, reflecting the use of common strategies during viral pathogenesis (12). Infection by HPVs leads to benign proliferative lesions or warts, which generally regress spontaneously. However, a subset of HPVs, referred to as high-risk HPVs are causally associated with the development of anogenital neoplasia (38). The productive life cycle of HPVs begins with infection of basal keratinocytes, where the viral DNA is established as an autonomously replicating nuclear plasmid with a low copy number. Expression of the viral early or regulatory genes leads to an expansion of the infected keratinocyte population and an alteration of the cellular differentiation program. Upon differentiation, the late or structural genes of HPVs are expressed, viral DNA is amplified to a high copy number, and progeny virions are produced (12).

Persistence of HPV DNA in the dividing basal cells is regulated by viral trans-acting factors which bind to sequences in the upstream regulatory region (URR) of the viral genome. These factors include the E1 and E2 proteins, which are necessary for viral replication (36). The URR of HPV31 can be divided into several functional segments (Fig. 1A): a 5′ region (5′-URR domain), an auxiliary enhancer (AE) domain, the cell-specific keratinocyte enhancer (KE) element, the minimal origin, and the P97 promoter region where early transcripts originate. The minimal origin was identified in transient replication assays and consists of an E1 binding site (E1BS), flanked upstream by E2BS2 and downstream by E2BS3 and E2BS4 (5). Replication studies with HPV11, -16, and -18 have identified similar elements (3). In HPV31, the KE (nucleotides [nt] 7495 to 7789) is the major transcriptional activator of viral early gene expression and contains binding sites for Ap1 and Oct1. In addition, a footprint which binds an uncharacterized factor (footprint 1 [Fp1] [14, 16]) is located at the 5′ terminus of the KE. Directly upstream of the KE is an AE domain comprised of E2BS1 and YY1 and TEF1 sites that augments KE function (14). Such factor binding sites are found in the URRs of related HPVs and have been characterized for their role in transcription (for a review, see reference 22). To date, the transcriptional activities of these elements in HPV31 have only been analyzed in transient transfection assays (14, 16, 17).

FIG. 1.

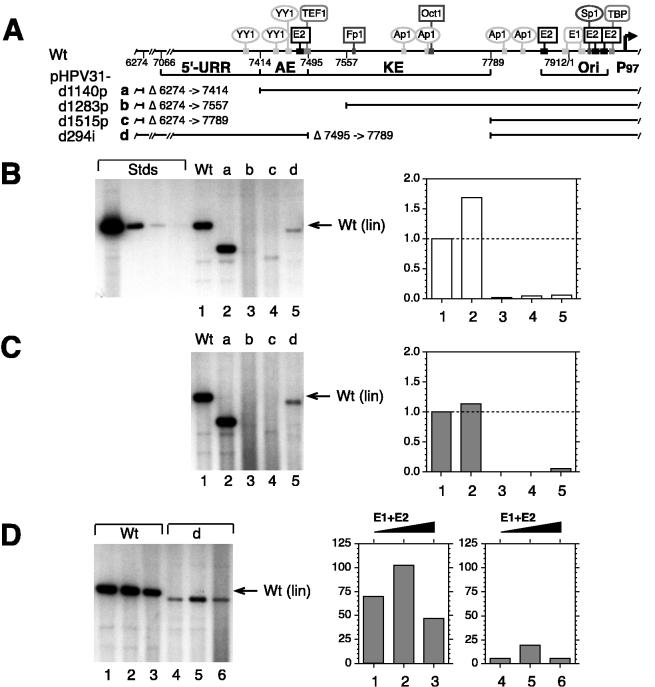

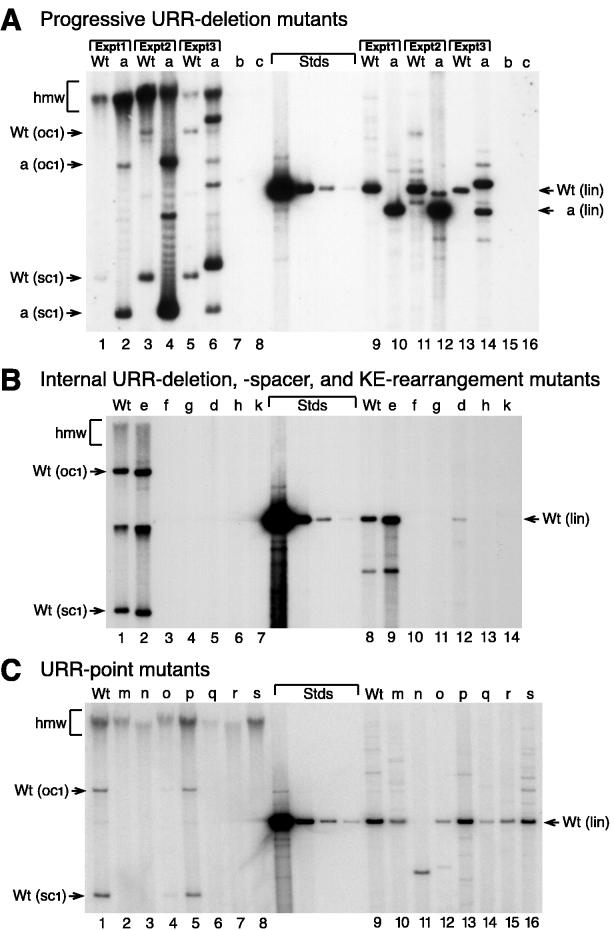

Transient DNA replication of HPV31 mutants with progressive or internal URR-deletions. (A) The schematic shows the HPV31 URR with DNA binding sites for viral and cellular factors. The positions of known URR elements, such as the 5′-URR domain, AE domain, KE element, and minimal origin of DNA replication (Ori) are indicated by brackets. Solid bars denote the retained DNA sequences, and the numbers refer to deleted nucleotide positions (described in Materials and Methods). Deletion (d) mutants of HPV31 contain progressive (p) or internal (i) URR deletions of the indicated size: a, pHPV31-d1140p (Δ6274 to 7414); b, pHPV31-d1283p (Δ6274 to 7557); c, pHPV31-d1515p (Δ6274 to 7789); and d, pHPV31-d294i (Δ7495 to 7789). (B) Autoradiogram of representative Southern blot of replicated (DpnI-resistant) viral DNAs from a transient replication assay with HPV31 wt and mutants in SCC13 cells (50% of total sample analyzed for each). Viral DNAs (equimolar amounts based on 3 μg of 7,912-bp wt HPV31) were excised from vector sequences, unimolecularly ligated, and transfected without E1 or E2 expression vectors (see Materials and Methods). DNA standards (Stds) with linearized wt HPV31, shown on the left, contain 500, 25, 2.5, and 0.5 pg of 7,912-bp DNA, respectively. The arrow on the right denotes the migration of linearized (lin) wt DNA. The graph shows the relative (to wt) replication activities, quantified from a phosphorimage of the Southern blot. Relative replication activities were comparable in four independent transfections. (C) Autoradiogram and graph from cotransfections of viral DNAs with equimolar amounts of E1 and E2 expression vectors. The graph shows relative (to wt) replication activities, quantified as described for panel B. (D) Increasing amounts of E1 and E2 expression vectors were titrated (molar ratios of expression vector to viral DNA of 0.33, 1.0, and 3.0) in the presence of constant amounts of viral wt and mutant d DNAs. Graphs show amounts of replicated DNA as a function of expression vector ratio, quantified from a phosphorimage of the Southern blot.

Studies with the fibropapillomavirus bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV1) have identified the minimal URR sequences for stable plasmid replication, consisting of six binding sites for E2 and one for E1 (24). However, the functional organization of the URR of BPV1 is significantly different from that of the high-risk genital HPVs (22, 37). Genital HPVs have four E2BS in this region, and it has been shown that only three of these sites are required for stable replication (33). The structure of the URR may reflect the different mechanisms of pathogenesis for these viruses; BPV1 infects both dermal and cutaneous epithelial cells, while genital HPVs persist exclusively in the mucosal epithelium. Methods for the genetic analysis of the productive viral life cycle of HPV31 and HPV18 have recently been developed. In these stable replication assays, cloned HPV DNA is excised from vector sequences, unimolecularly ligated, and transfected into normal human keratinocytes. Immortalized cell lines can be established, which maintain the viral DNA as stably replicating plasmids (6, 7). Upon differentiation in organotypic raft culture or suspension in methylcellulose, these cells induce viral late functions, including activation of late gene expression and genome amplification (7, 28).

Using these methods, we have systematically analyzed the role of URR sequences 5′ to the minimal origin in plasmid replication during different phases of the HPV31 life cycle. Previous studies have relied largely on transient assays using heterologous expression vectors for E1 and E2. Our replication studies with entire HPV31 genomes indicate that the KE directly modulates replication efficiency and is essential for expression of E1 and E2. Multiple binding sites in the URR for Ap1, Sp1, and Fp1 are necessary for transient and stable replication of HPV31 genomes. In contrast, the 5′-URR domain and the Oct1 DNA binding site were found to be dispensable for transient and stable viral replication as well as for viral DNA amplification under vegetative conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

All wild-type (wt) and mutated plasmids, are numbered according to the standard nucleotide number assignment as published for HPV31 (8). Three parental HPV31 wt DNAs were used in this study to facilitate the construction of mutants: (i) pBR322-HPV31 (7), which contains the pBR322 vector at the unique EcoRI site of HPV31; (ii) pBRmin-HPV31, which contains a pBR322 vector fragment (ClaI to Eco47III) at the unique EcoRI site of HPV31; and (iii) pUCmin-HPV31, which contains a pUC vector fragment (AflIII to SspI) at the unique XbaI site of HPV31. A schematic map of the URR is shown for each set of mutants in panels A of Fig. 1 through 4. The locations of all DNA binding sites for cellular and viral factors in the URR are numbered ascendingly in the sense direction of viral transcription (5′ to 3′). The plasmid nomenclature for the HPV31 genomes used in this study specifies the nature of a mutation: deletion (d), spacer replacement (s), rearrangement (r), insertion (i), or point mutation (p). The size of a deletion, spacer, rearranged fragment, or insertion is indicated by the number of base pairs. Finally, deletions in the URR are classified as progressive (p) or internal (i), insertions are indicated as upstream (u) or downstream (d) with respect to the origin, and rearrangements of the KE are designated sense (s) or antisense (a). Mutations in DNA binding sites are denoted with the name of the transcription factor.

FIG. 4.

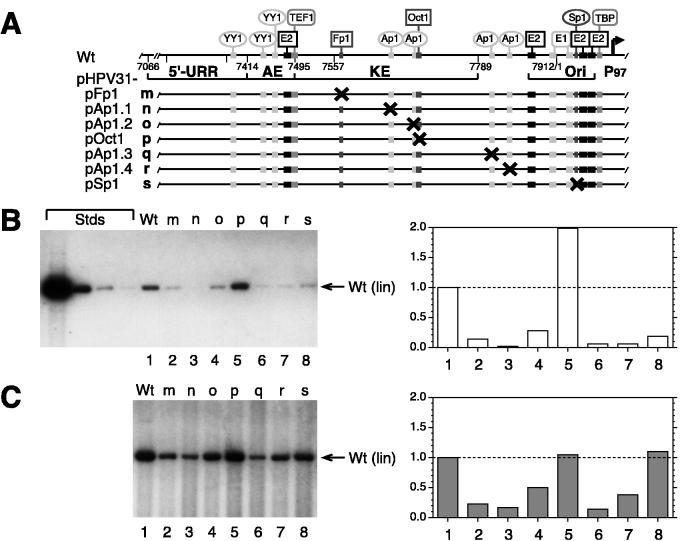

Transient replication of HPV31 DNAs with point mutations in the URR. (A) The schematic elements of the HPV31 URR are the same as described in the legend to Fig. 1. In addition, specific DNA binding sites of transcription factors marked with × are mutated (described in Materials and Methods). Point mutations (p) are designated with factor name and binding site number (5′ to 3′ on HPV31 sense strand): m, pHPV31-pFp1; n, pHPV31-pAp1.1; o, pHPV31-Ap1.2; p, pHPV31-Oct1; q, pHPV31-Ap1.3; r pHPV31-Ap1.4; s, pHPV31-Sp1. (B) Autoradiogram of representative Southern blot of replicated (DpnI-resistant) viral DNAs from a transient replication assay with HPV31 wt and mutants in SCC13 cells (50% of total sample analyzed for each). Viral DNAs (equimolar amounts based on 3 μg of 7,912-bp wt HPV31) were transfected without expression vectors. (C) Autoradiogram and graph from cotransfections of viral DNAs with equimolar amounts of E1 and E2 expression vectors. DNA standards (Stds), migration of viral DNA, and quantification of the relative replication levels (B and C) are described for Fig. 1B.

(i) Deletions.

pBR322-HPV31 was used as the parental DNA for the following URR deletions (Δ) between unique restriction sites: pHPV31-d1140p (ΔBlpI to RsrII, Δnt 6274 to 7414), pHPV31-d1283p (ΔBlpI to SpeI, Δnt 6274 to 7557), pHPV31-d1515p (ΔBlpI to 3′-PmeI, Δnt 6274 to 7789), and pHPV31-d294i (Δ5′-PmeI to 3′-PmeI, Δnt 7495 to 7789). In each plasmid, the deletions were replaced with a BamHI linker (5′-dCGGATCCG). pHPV31-d143i (ΔRsrII to SpeI, nt 7414 to 7557) was prepared similarly but without a linker at the deletion. pHPV31-d102i was prepared by replacing the corresponding wt sequences in pUCmin-HPV31 with the Bst 1 107I-SpeI fragment from pBas102del (14).

(ii) Spacer replacements.

pUCmin-HPV31 was used as parental DNA for the following spacer replacement mutants. pHPV31-s143i contains a PCR-generated DNA spacer from the hygromycin resistance gene (nt 133 to 268 of aminoglycoside phosphotransferase [Aph] coding sequence [9]) inserted between the RsrII and SpeI sites. pHPV31-s294i was prepared by inserting a spacer (nt 133 to 412 of Aph coding sequence) into the BamHI site of pHPV31-d294i and then transferring the BlpI-to-HindIII fragment into pUCmin-HPV31. The DNA spacers do not contain consensus sites for the common transcription factors that bind to the HPV31 URR.

(iii) KE rearrangements and duplications.

pBRmin-HPV31 was used as parental DNA for the following mutants. The KE fragment (5′-PmeI to 3′-PmeI, nt 7495 to 7789) was deleted and inserted at HpaI (nt 215) in sense orientation for pHPV31-r294s and in antisense orientation for pHPV31-r294a. Duplication of the KE was performed with pBR322-HPV31. A second KE element was inserted in sense orientation at RsrII (nt 7414) for pHPV31-i294u or at HpaI for pHPV31-i294d.

(iv) URR binding site mutants.

All mutants in this panel are based on pBR322-HPV31. pHPV31-pFp1 (defective Fp1 [17]), -pAp1.1 (defective Ap1 binding site 1 [Ap1BS1]), -pAp1.2, -pOct1, -pAp1.3, -pAp1.4, and -pSp1 contain multiple point mutations within the indicated factor binding site and were previously characterized in transient URR reporter and gel mobility shift assays (14, 17).

(v) Expression vectors.

pSG-E1 and pSG-E2 are pSG5-based expression vectors (Stratagene) containing the HPV31 E1 and E2 coding sequences, respectively. These expression vectors support replication of HPV31 origin plasmids in transient assays (5).

Transient replication assay. (i) DNA preparations.

Bacterial vector sequences were first cleaved from the viral DNA (3 μg of 7,912-kbp wt or equimolar amounts of mutant) with the appropriate restriction enzyme. Digested DNAs were unimolecularly ligated at 15°C overnight (850 μl, 7.5 Weiss units of T4 DNA ligase in 1× reaction buffer; GIBCO-BRL). Ligated DNAs were precipitated with 20 μg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA (Sigma), NaCl to 1 M (final concentration), and 0.6 volume of 2-propanol. DNAs were pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). For transfections with expression vectors, equimolar (based on 7,912-kbp HPV31) amounts of pSG-E1 and pSG-E2 were included in the final DNA mixture (20 μl).

(ii) Transient transfections and DNA isolation.

Human squamous cell carcinoma (SCC13 [25]) cells were maintained in E medium on cocultured, mitomycin-treated J2-3T3 fibroblast feeders as described previously (18). Transfection by electroporation was carried out as described previously (5, 36), with the following modifications. SCC13 cells (5 × 106; 200 μl) in electroporation medium (complete E medium supplemented with HEPES [pH 7.2] to 25 mM) were mixed with DNA in electroporation cuvettes (0.4-cm gap width) on ice, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, pulsed once (250 V, 960 μF; Bio-Rad GenePulser), and immediately plated onto 10-cm-diameter dishes containing mitomycin-treated J2 feeder cells and electroporation medium. At 1, 2, and 4 days after transfection, cells were refed with fresh E medium. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated at 5 days posttransfection with a modified Hirt protocol (11). Sample dishes were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and placed on ice. Cells were scraped in resuspension buffer (0.6 ml; 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA), and transferred to an ultracentrifuge tube (11 by 34 mm, thick-walled polycarbonate; Beckman). Samples were digested at 37°C for at least 3 h with proteinase K (to 0.2 μg/μl) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; to 0.2% [wt/vol]). The NaCl concentration of samples was adjusted to 1 M, high-molecular-weight DNA and cellular debris was precipitated by overnight incubation on ice. After ultracentrifugation (100,000 rpm, 20 min at 4°C, TLA100.2 rotor; Beckman), supernatants were extracted with phenol and chloroform and precipitated with 0.6 volume of 2-propanol. Samples were collected by centrifugation, washed with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and resuspended in TE (20 μl) with RNase A (to 20 μg/ml). One half of each sample was digested overnight with 8 U of DpnI and 7 U of linearizing enzyme (either HpaI, BanII, or AatII).

(iii) DNA analysis.

Digested DNAs were resolved on 0.8% agarose gels, blotted onto a neutral nylon membrane (Magna) by high-salt transfer (2), and immobilized by UV cross-linking (Stratagene). Hybridization was carried out with a subgenomic HPV31 DNA probe (HpaI-EcoRI fragment) radiolabeled by random priming (Pharmacia) in a nonaqueous solution (50% [vol/vol] formamide, SSC [850 mM sodium chloride, 100 mM sodium citrate {pH 7.0}], Denhardt’s solution [0.1% {wt/vol} each of bovine serum albumin, polyvinyl alcohol, and Ficoll], 5% [wt/vol] dextran sulfate, 1% [wt/vol] SDS, 100 μg of denatured sonicated salmon sperm DNA per ml) at 42°C. Blots were washed under stringent conditions (Magna), autoradiographed (Amersham Hyperfilm MP), and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Four independent transfections per sample were analyzed in separate transient replication assays which produced comparable relative replication activities. To allow comparison between different transfections, all Southern blots contained DNA standards (500, 25, 2.5, and 0.5 pg of 7,912-bp HPV31 DNA). Since not all cells take up DNA in transient transfections, these standards do not represent copy numbers per cell.

Stable replication assay. (i) Stable transfections.

Viral DNAs were digested and unimolecularly ligated as described for the transient replication assay. Transfections and drug selection were carried out as published elsewhere (7), with the following modifications. Samples were coprecipitated with equimolar amounts of the selectable marker plasmid pSV2neo (30) but without carrier DNA, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in TE (50 μl). Primary human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) were grown to 60% confluence in 6-cm-diameter dishes with KGM medium (Clonetics). Transfection mixtures (500 μl) were prepared with the sample DNAs and Lipofectamine (20 μl; GIBCO-BRL) in KGM medium and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Sample dishes were washed with KGM medium and incubated with the transfection mixture in KGM medium (1.5 ml, total volume) for 5 h at 37°C. KGM medium was added to 5 ml, and incubation continued overnight. One day posttransfection, transfected HFKs were plated into 10-cm-diameter dishes containing mitomycin-treated J2 feeder cells in E medium. Two days posttransfection, the growth medium was changed to E medium supplemented with 200 ng of murine epidermal growth factor per ml (E+EGF medium). Transfected cells were selected for 5 days with G418 sulfate (200 μg/mL [wt/vol]; GIBCO) in E+EGF medium, and treated J2 feeder cells were replenished every 2 days. After selection, cells were grown in E+EGF medium until visible colonies appeared (typically 2 weeks), trypsinized, and passed as mass cultures into several 10-cm-diameter dishes for DNA and cell stock preparation.

(ii) DNA analysis.

Total cellular DNA was isolated from nearly confluent mass cultures by lysis with proteinase K and SDS as described elsewhere (29). Sheared DNA samples (5 μg) were digested with DpnI (20 U) only; unsheared samples were digested with DpnI and a linearizing enzyme for the viral DNA (20 U of each). Samples were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Southern hybridization as described for the transient replication assay.

DNA amplification assay.

HFK-based cell lines with stably replicating wt or mutants of HPV31 were grown in semisolid medium (1.6% [wt/vol] methylcellulose in complete E medium with 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.2]) as described elsewhere (28). Cells were recovered immediately from the methylcellulose suspension (0 h) or after 24 h, and total cellular DNA was isolated and analyzed as described above.

RESULTS

Loss of the central URR domains diminishes transient DNA replication efficiency.

To investigate if URR sequences in addition to the minimal origin played a role in replication of HPV31, we constructed a series of deletion mutants in the background of the entire viral genome (Materials and Methods; Fig. 1A). Progressive deletions extended from within the L1 open reading frame (from nt 6274) to sequences in the URR: pHPV31-d1140p (to nt 7414), pHPV31-d1283p (to nt 7557), or pHPV31-d1515p (to nt 7789). A mutant with an internal deletion of the KE (pHPV31-d294i [from nt 7495 to 7789]) was also constructed. These deletions mutants were first tested in a transient replication assay using HPV-negative human squamous cell carcinoma (SCC13) cells. Transient replication assays most closely mimic the establishment phase of the HPV life cycle. Therefore, analysis of transient replication activities of mutant viral genomes identifies cis and trans replication defects. A previous study demonstrated that the transient replication behavior of HPV31 mutants in SCC13 cells is comparable to that in primary human keratinocytes (15). Unimolecularly ligated HPV31 DNAs without bacterial vector sequences were transfected into 5 × 106 SCC13 cells by electroporation, either by themselves or with expression vectors for E1 and E2. Heterologous expression of the viral replication factors was necessary for those HPV31 mutants where mutation of the known transcriptional control elements was expected to diminish E1 and E2 expression and thus lead to loss of replication. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated from cells 5 days posttransfection, and one half of each sample was analyzed by Southern blotting, autoradiography, and phosphorimaging (Materials and Methods).

As shown in Fig. 1B, replication efficiencies of HPV31 mutants with deletions that included the AE domain and/or the KE element were less than 10% of the wt level (lanes/columns 3 and 4). Similarly, the mutant with a deleted KE element also replicated at a low level (lane/column 5), indicating that deletion of the central URR domains can affect viral plasmid replication. To determine if the replication phenotype of these deletion mutants was the result of reduced E1 and E2 expression, or rather reflected a direct modulation of replication, transient assays were also performed with cotransfected expression vectors for E1 and E2. As shown in Fig. 1C, mutants with progressive deletions that include the AE domain (pHPV31-d1283p) and the KE element (pHPV31-d1515p) or the KE alone (pHPV31-d294i) had much lower than wt levels of replication when cotransfected with E1 and E2 vectors (lanes/columns 3 to 5). All transient replication studies were carried out with four independent transfections per sample which produced comparable relative replication activities.

To test if the low replication efficiency of pHPV31-d294i in the presence of expression E1 and E2 vectors was caused by insufficient amounts of the viral replication factors, we performed titrations with increasing molar ratios of E1 and E2 vector DNAs based on a constant amount of viral genome. As shown in Fig. 1D, the replication efficiency of the KE deletion mutant was not restored to wt levels even when the ratio was increased 10-fold, from 0.33 to 3 (lanes/columns 4 to 6). In contrast to the phenotypes of the central URR deletion mutants, removal of the 5′ region from the viral genome (pHPV31-d1140p) increased replication efficiency above wt levels (Fig. 1B and C, lanes/columns 2), indicating that these DNA sequences may contain elements that negatively regulate viral replication. The behavior of the URR deletion mutants indicates that both the AE domain and the KE element are necessary for efficient transient plasmid replication of HPV31. Mutants with AE and KE deletions also replicate significantly below wt levels when the E1 and E2 expression vectors are cotransfected with the viral genomes, suggesting that the central URR domains can regulate expression of the viral replication factors as well as modulate replication directly.

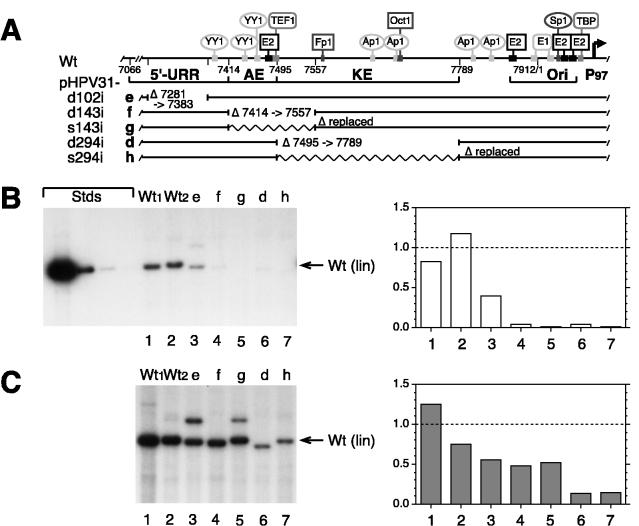

Replacement of URR deletions with spacers does not increase DNA replication efficiencies.

The low-replication phenotype of most HPV31 mutants with a KE deletion (Fig. 1A, lanes/columns 3 to 5) could also have been caused by bringing cis-acting elements closer to the minimal origin that could down-regulate E1 and E2 expression or replication. To test this possibility, we constructed a series of HPV31 genomes that contained small internal deletions in the URR. For a subset of these mutants, spacer DNA was inserted into the deletions which was derived from the Aph coding region (9). The selected regions of Aph do not contain consensus sites for the known cellular transcription factors that bind to the URR. Mutant pHPV31-d102i contains a deletion (nt 7281 to 7383) in the 5′ segment of the URR between the late polyadenylation signal and the 5′-most YY1 DNA binding site (Fig. 2A) (14). In pHPV-d143i, the AE domain (nt 7414 to 7557) was deleted. This URR domain contains two YY1 sites, one TEF1 site, and the 5′-most E2BS and functions as a transcriptional activator (14). In mutants pHPV31-s143i and pHPV31-s294i, each deletion was replaced with a DNA spacer of the same size.

FIG. 2.

Transient DNA replication of HPV31 mutants with internal URR deletions and spacer replacements. (A) The schematic elements of the HPV31 URR are the same as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Zigzag lines denote spacer DNA sequences inserted into the deletions (described in Materials and Methods). Deletion (d) and spacer (s) mutants of HPV31 with internal (i) URR deletions or spacer replacements of the indicated size: e, pHPV31-d102i (Δ7281 to 7383); f, pHPV31-d143i (Δ7414 to 7557); g, pHPV31-s143i (Δ7495 to 7557 with spacer), d, pHPV31-d294i (Δ7495 to 7789); h, pHPV31-s294i (Δ7495 to 7789 with spacer). (B) Autoradiogram of representative Southern blot of replicated (DpnI-resistant) viral DNAs from a transient replication assay with HPV31 wt and mutants in SCC13 cells (50% of total sample analyzed for each). Viral DNAs (equimolar amounts based on 3 μg of 7,912-bp wt HPV31) were transfected without expression vectors. Wt1 and Wt2 pBR-based and pUC-based wt DNAs. (C) Autoradiogram and graph from cotransfections of viral DNAs with equimolar amounts of E1 and E2 expression vectors. DNA standards (Stds), migration of viral DNA, and quantification of the relative replication levels (B and C) are described in the legend to Fig. 1B.

This panel of small deletion and spacer mutants was then analyzed in a transient replication assays. When transfected without E1 and E2 expression vectors, mutant pHPV31-d102i (Δ7281 to 7385) was found to replicate at 40% of wt levels (Fig. 2B, lane/column 3). Mutants with other deletions (pHPV31-d143i and -d294i) or spacers (pHPV31-s143i and -s294i) replicated with less than 10% of wt efficiency (lanes/columns 4 to 7). When these HPV31 DNAs were cotransfected with E1 and E2 expression vectors, the AE-specific deletion and spacer mutants were found to replicate at about 50% of wt levels, while the KE-specific mutants were below 20% of wt levels (Fig. 2C, lanes/columns 4 to 7). These observations indicate that (i) deletions of either the AE domain (nt 7414 to 7557) or the KE element (nt 7495 to 7789) diminish expression of the viral replication factors, (ii) the AE domain has a smaller direct effect on replication than the KE element, and (iii) the replication efficiencies resulting from deletion of these URR sequences cannot be restored by inserting spacer sequences.

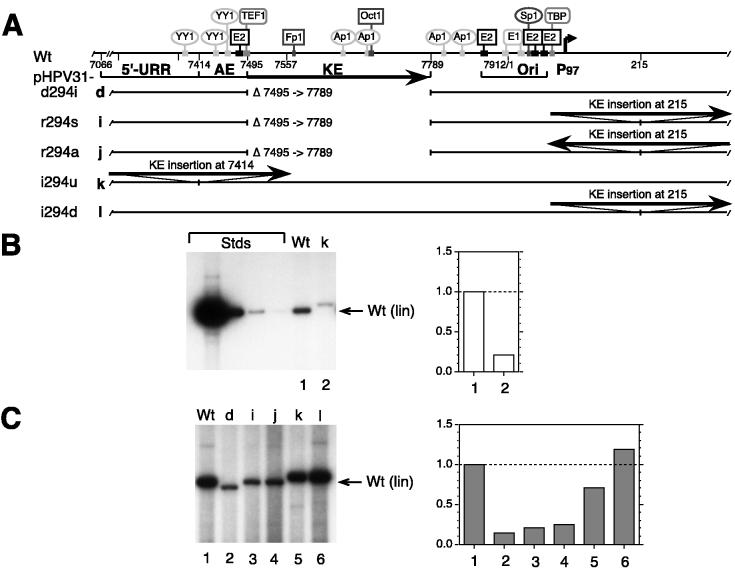

The replication function of the KE is dependent on the position and orientation of the element and is not cooperative when present in multiple copies.

Our analysis of HPV31 mutants with progressive deletions into the URR or smaller internal deletions indicated that the central URR domains contain DNA sequences that modulate replication in cis. In polyomaviruses, elements that overlap with the transcriptional enhancer and augment replication of the minimal origin have been identified. This replication enhancer activity was shown to be independent of the position or orientation of the element (4). To test if the KE (nt 7495 to 7789) of HPV31 could function as a replication enhancer, we generated a panel HPV31 mutants that contained repositioned or duplicated KE elements. In mutants pHPV31-r294s and pHPV31-r294a, the KE was deleted from its wt position and inserted at nt 215 in the same orientation as in a wt genome (sense) and antiparallel, respectively (Fig. 3A). The inserted KE element is located about 210 nt 3′ to the center of the palindromic E1BS in the origin, which is similar to the distance of a wt KE element 5′ of the origin (130 nt). To test potential cooperativity of multiple KE elements, a second KE was inserted upstream at nt 7414 (pHPV31-i294u) or downstream at nt 215 (pHPV31-i294d).

FIG. 3.

Transient DNA replication of HPV31 mutants with deletions, rearrangements, or insertions of the KE. (A) The schematic elements of the HPV31 URR are the same as described in the legend to Fig. 1. In addition, KE elements inserted into the viral DNA at given nucleotide positions are shown as solid lines with arrow tips, indicating the normal KE orientation (described in Materials and Methods). Deletion (d), rearrangement (r), or insertion (i) mutants of HPV31 where the 294-bp KE fragment is deleted or placed in sense (s) or antisense (a) orientation, upstream (u) or downstream (d) of the origin: d, pHPV31-d294i (Δ7495 to 7789); i, pHPV31-r294s (Δ7495 to 7789, KE at nt 215 in sense); j, pHPV31-r294a (Δ7495 to 7789, KE at nt 215 in antisense); k, pHPV31-i294u (new KE at nt 7414); l pHPV31-i294d (new KE at nt 215). (B) Autoradiogram of representative Southern blot of replicated (DpnI-resistant) viral DNAs from a transient replication assay with HPV31 wt and mutants in SCC13 cells (50% of total sample analyzed for each). Viral wt and mutant k DNAs (equimolar amounts based on 3 μg of 7,912-bp wt HPV31) were transfected without expression vectors. (C) Autoradiogram and graph from cotransfections of viral DNAs with equimolar amounts of E1 and E2 expression vectors. DNA standards (Stds), migration of viral DNA, and quantification of the relative replication levels (B and C) are described for Fig. 1B.

All KE rearrangement mutants were analyzed in a transient replication assay with cotransfected E1 and E2 expression vectors as described in Materials and Methods. Since pHPV31-i294u is the only mutant genome that contains an intact early transcription unit, it was also tested without E1 and E2 expression vectors. Duplication of the KE element in pHPV31-i294u diminished replication to 20% of wt levels (Fig. 3B, lane/column 2) in the absence of E1 and E2 expression vectors, indicating that viral gene expression was possibly affected by this mutation. When expression vectors were cotransfected with pHPV31-i294u, replication was not completely restored to wt levels, suggesting that the duplication of the KE element also interfered directly with replication (Fig. 3C, lane/column 5). When the KE element was duplicated at both sides of the minimal origin in pHPV31-i294d, the replication efficiency with E1 and E2 expression vectors was similar to wt levels (lane/column 6).

In cotransfections with E1 and E2 expression vectors, the mutant genomes containing a KE element downstream of the minimal origin, pHPV31-r294s and pHPV31-r294a, replicated as inefficiently as the KE deletion mutant pHPV31-d294i (Fig. 3C, lanes/columns 2 to 4). Replication of these KE rearrangement mutants at less than 20% of wt levels, therefore, indicates that the replication efficiency of HPV31 genomes that lack a wt KE cannot be restored by inserting a KE element downstream of the origin. These findings demonstrate that activation of replication by the KE element is position and orientation dependent. Since duplication of the element also did not cooperatively activate replication, it appears that the entire KE element, which was mapped in earlier transcriptional studies, does not act as a replication enhancer.

DNA binding of transcription factors to their cognate sites in the URR activates DNA replication primarily through an increase in viral gene expression.

To test if binding of specific transcription factors to the URR could contribute to the activation of DNA replication, HPV31 genomes with mutated factor binding sites were tested in a transient replication assay. Previous transient studies with reporter plasmids that contained mutated URR sequences identified specific binding sites that can activate transcription. These include four binding sites for Ap1, one each for Sp1 and Oct1, and the uncharacterized Fp1 (14, 16). The following panel of viral genomes contain point mutations which abrogate binding of the factors to the specified sites (in 5′-to-3′ direction on the HPV31 sense strand [Fig. 4A]): pHPV31-pFp1, pHPV31-pAp1.1 (Ap1BS1), pHPV31-pAp1.2, pHPV31-pOct1, pHPV31-pAp1.3, pHPV31-pAp1.4, and pHPV31-pSp1. These binding site mutations were previously tested in gel mobility shift assays and found to be defective for factor binding (14, 16).

Mutating one of the four Ap1 sites in the URR diminished replication to less than 10% (site 1, 3, or 4) or 30% (site 2) of wt levels in the absence of E1 and E2 expression vectors (Fig. 4B, lanes/columns 3, 4, 6, and 7). Similarly, abrogation of DNA binding by Sp1 or the factors comprising Fp1 also reduced replication to about 20% of wt levels (lanes/columns 8 and 2). The only mutated genome in the panel that replicated better than wt was pHPV31-pOct1 (lane/column 5). When these viral DNAs were cotransfected with E1 and E2 expression vectors, the replication efficiencies of most mutants increased to 40% or more of the wt level (Fig. 4C, lanes/columns 4, 5, 7, and 8). Only pHPV31-pFp1, -pAp1.1, and -pAp1.3 replicated inefficiently at about 20% of wt levels with E1 and E2 vectors (lanes/columns 2, 3, and 6). These results indicate that (i) most transcription factors binding in the URR of HPV31 modulate viral replication through expression of the E1 and E2 genes and (ii) mutations in Fp1, Ap1BS1, or Ap1BS3 affect viral transcription as well as replication directly.

Deletions of the 5′-URR domain do not diminish stable DNA replication.

We next sought to identify sequences within the URR that in addition to the minimal origin are required for stable replication. In contrast to transient replication assays which mimic the establishment phase of HPV infection, stable replication assays with primary human keratinocytes allow the examination of the requirements for maintenance. Stable replication of HPV genomes as autonomously replicating nuclear plasmids depends on the complex interaction of viral and cellular processes. Previous studies have demonstrated significant differences between transient and stable assays (15, 32, 33).

To test which URR sequences were necessary for stable replication, we carried out stable replication assays with a subset of the HPV31 mutants analyzed in the transient studies (see Materials and Methods). Typically, primary cell lines established by transfection with wt HPV31 contain 20 to 50 viral genomes per cell (7). The following groups of mutated HPV31 genomes all contain intact E6 and E7 genes which are required for full immortalization of primary cells (20): progressive URR deletion mutants pHPV31-d1140p, -d1283p, and -d1515p (Fig. 1A); internal URR deletion and spacer mutants pHPV31-d102i, -d143i, -s143i, -d294i, and -s294i (Fig. 2A); the KE duplication mutant pHPV31-i294u (Fig. 3A); and all of the URR point mutants pHPV31-pFp1, -pAp1.1, -pAp1.2, -pOct1, -pAp1.3, -pAp1.4, and -pSp1 (Fig. 4A). HPV31 plasmids were digested to cleave the bacterial vector sequences from the viral DNA, unimolecularly ligated, and transfected into primary HFKs with a selectable marker and no expression vectors for E1 and E2. Transfected cells were selected; drug-resistant colonies were pooled and expanded. Total cellular DNA was isolated from these mass culture cell lines at passage 3 posttransfection and analyzed by Southern blotting. Several different topological forms of viral DNA can be distinguished in sheared total cellular DNA: (i) slowly migrating, high-molecular-weight smears (hmw), (ii) open-circle monomers (oc), and (iii) fast-migrating supercoiled monomers (sc) (Fig. 5). Hybridization signals at position i generally indicate integrated or highly multimeric viral plasmid DNA, while those at positions ii and iii demonstrate autonomous viral replication. To estimate viral copy number per cell, total unsheared cellular DNA was digested with an enzyme that linearizes viral plasmid monomers or reduces tandemly integrated species to unit length.

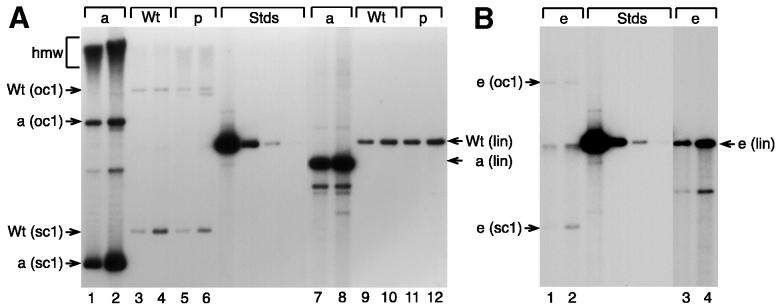

FIG. 5.

Stable DNA replication of HPV31 mutants. Autoradiograms of representative Southern blots show HPV31 mutants tested in stable replication assays. Total cellular DNA was isolated from mass cultures of stably transfected primary cells and analyzed for the presence of viral DNA (Materials and Methods). All panels show sheared/undigested DNA (5 μg) on the left, unit-length DNA standards (500, 25, 2.5, and 0.5 pg of 7,912-bp wt HPV31 DNA; equivalent to about 100, 5, 0.25, and 0.1 viral genomes per cell) in the center, and unsheared/linearized DNA (5 μg) on the right. Autonomous viral plasmid replication is indicated by supercoiled monomeric (sc1) and open-circle monomeric (oc1) bands (arrows on left). Hybridization of high-molecular-weight DNA (hmw) generally indicates the presence of plasmid multimers or integrated viral DNA. Unit-length viral DNAs (lin) from digestion with a unique restriction enzyme is obtained from autonomously replicating plasmid DNA or tandemly integrated viral DNA and is an indicator of viral copy number (arrows on the right). (A) HPV31 mutants with progressive URR deletions (maps in Fig. 1A): sheared samples (lanes 1 through 8) of wt and mutant pHPV31-d1140p (a) from three independent transfections, and mutants pHPV31-d1283p (b) and pHPV31-d1515p (c). Linearized samples are shown in the same order (9 through 16). (B) HPV31 mutants with internal URR deletions, DNA spacers, or KE insertion (maps in Fig. 2A and 3A): sheared samples (lanes 1 through 7) of wt and mutants pHPV31-d102i (e), pHPV31-d143i (f), pHPV31-s143i (g), pHPV31-d294i (d), pHPV31-s294i (h), and pHPV31-i294u (b). Linearized samples are shown in the same order (8 through 14). (C) HPV31 mutants with defective factor binding sites (maps in Fig. 4A): sheared samples (lanes 1 through 8) of wt, pHPV31-pFp1 (m), pHPV31-pAp1.1 (n), pHPV31-Ap1.2 (o), pHPV31-Oct1 (p), pHPV31-Ap1.3 (q), pHPV31-Ap1.4 (r), and pHPV31-Sp1 (s). Linearized samples are shown in the same order (9 through 16).

Deleting URR sequences 5′ of nt 7414 did not adversely affect stable replication. In three independent experiments with primary HFKs from different donors, the mutant pHPV31-d1140p replicated extrachromosomally as an intact monomeric (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 4) or, in one case, rearranged (lane 6) plasmid. Its estimated DNA copy number per cell was, on average, about 1.8-fold higher than that for wt DNA. In addition, a smaller deletion in the 5′-URR domain was found to replicate stably at wt levels (Fig. 5B, lane 2). HPV31 genomes which contained deletions of the AE domain (pHPV31-d1283p and -d143i) or the KE element (pHPV31-d1515p and -d294i) or had DNA spacers in the respective deletions (pHPV31-s143i and -s294i) did not replicate stably. Although the detection limit of our assay was better than 0.1 viral copy per cell (0.5 pg [Fig. 5A, center]), consistently, no viral signal was detectable in the total DNA samples (Fig. 5A, lanes 7 and 8; Fig. 5B, lanes 3 through 6). Similarly, the HPV31 mutant containing an upstream duplication of the KE element (pHPV31-i294u) did not replicate stably (Fig. 5B, lane 7). The inability of these mutants to replicate stably thus correlated with their low levels of replication in the transient assays without E1 and E2 expression vectors. Finally, we tested the panel of HPV31 genomes with inactivated factor binding sites (pHPV31-pFp1, -pAp1.1, -pAp1.2, -pOct1, -pAp1.3, -pAp1.4, and -pSp1 [Fig. 4A]) in a stable replication assay. Again, only pHPV31-pOct1, which could replicate efficiently in the transient assay, was also able to replicate stably (Fig. 5C, lane 5). Genomes containing mutations in other binding sites produced high-molecular-weight hybridization signals in the stable replication assay, indicating that the viral DNA was integrated into the cellular genome (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 8). In all stable replication assays that were performed, we observed some integrated viral DNA with wt DNA (Fig. 5A, lanes 1, 3, and 5; Fig. 5B, lane 1; Fig. 5C, lane 1). However in all cases, wt HPV31 replicated as a monomeric plasmid with prominent supercoiled and open-circle bands (Fig. 5). Occasionally, both monomeric and rearranged species of wt or mutant HPV31 DNA were found in the same sample (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 2), which may have been caused by improper recircularization of the viral genomes prior to transfection.

The 5′-URR domain and the Oct1 DNA binding site are not required for viral DNA amplification.

Differentiation of the HPV-infected host cells is necessary for the ability of papillomaviruses to amplify viral genomes and induce late gene expression (1, 7, 13, 19). HPV31-harboring keratinocytes grown in semisolid medium (10) undergo cellular differentiation and induce viral genome amplification in about 20% of cells (27, 28). To test the effects of specific mutations on the ability to amplify viral DNA, the cell lines that could be established with stably replicating HPV31 mutants in our preceding analyses were subjected to growth in methylcellulose (see Materials and Methods). At 0- and 24-h time points, total cellular DNA was isolated and analyzed by Southern blotting.

The HPV31 genomes that contain deletions in the 5′-URR (pHPV31-d1140p and -d102i [Fig. 1A and 2A]) were able to amplify their copy number about twofold above the levels in undifferentiated monolayer cultures (Fig. 6A and B, lanes 2 versus lanes 1). This ratio of increase was similar to the observed amplification of wt DNA (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 2 and 4) and is equivalent to about a 10-fold increase in viral genomes in amplification-competent cells. The pHPV31-pOct1 point mutant (Fig. 4A) could also amplify its copy number (Fig. 6A, lane 6 versus lane 5). We therefore conclude that the 5′-URR domain and the Oct1 binding site are nonessential for HPV31 genome amplification.

FIG. 6.

DNA amplification of stably replicating HPV31 mutants. Autoradiograms of representative Southern blots show stably replicating HPV31 mutants in differentiating primary keratinocytes. Cells were grown in semisolid medium for 0 h (odd lane numbers) and 24 h (even lane numbers) to induce differentiation and viral DNA amplification. Total cellular DNA was isolated, analyzed for viral DNA, and arranged on the blots as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 5. All panels show sheared/undigested DNA (5 μg) on the left, unit-length DNA standards (500, 25, 2.5, and 0.5 pg of 7,912-bp wt HPV31 DNA; equivalent to about 100, 5, 0.25, and 0.1 viral genomes per cell) in the center, and unsheared/linearized DNA (5 μg) on the right. (A) Sheared (lanes 1 through 6) and linearized (7 through 12) samples of mutant pHPV31-d1140p (a [Fig. 1A]), wt, and mutant pHPV31-Oct1 (p [Fig. 4A]), uninduced (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and induced (lanes 2, 4, and 6). (B) Sheared (lanes 1 and 2) and linearized (lanes 3 and 4) samples of mutant pHPV31-d102i (e [Fig. 2A]), uninduced (lanes 1 and 3) and induced (lanes 2 and 4).

DISCUSSION

We have systematically examined the effects of URR sequences outside the minimal origin on the replication activity of HPV31 in different phases of the viral life cycle by carrying out transient, stable, and DNA amplification assays with a series of viral genomes containing URR deletions, spacer replacements, or point mutations. Consistent with the previous findings that the KE is necessary for efficient transcription of the early viral genes in general, we demonstrate here that it is specifically required for expression of the replication proteins E1 and E2 and that it also modulates replication activity in cis, since addition of expression vectors for E1 and E2 does not restore the replication efficiencies of KE mutants to wt levels. The E1 and E2 expression vectors used in this study have been shown to support replication of an HPV31 minimal origin plasmid (5). While our URR mutations of the transcriptional enhancer sequences of HPV31 likely affect the expression of most early genes, the observed reduction of transient replication efficiency in SCC13 cells is, we believe, caused by decreased E1 and E2 levels. Since HPV31 mutants defective for E6 or E7 expression can replicate in transiently transfected SCC13 cells comparable to wt levels (35), altered expression of these oncoproteins does not play a major role in modulating the transient replication activities of HPV31 enhancer mutants.

Our observation that the replication activities of HPV31 genomes that contain a deletion of the KE or a neutral DNA spacer are comparable and below wt levels suggests that the KE element may contain sequences that directly activate replication. However, unlike the function of the replication enhancer in polyomavirus (21), activation of HPV31 replication by the KE is dependent on the specific position and orientation of the element in the viral genome, indicating that the KE is not a replication enhancer. The inefficient replication of HPV31 genomes containing point mutations in transcription factor binding sites demonstrated that the primary function of these sites is in the regulation of E1 and E2 expression. However, even in the presence of E1 and E2 expression vectors, viral genomes with defective Ap1BS1 or Ap1BS3 replicated only at about 30% of wt levels. These results indicate that these two Ap1 sites, which are equidistant from each other and the minimal origin, appear to modulate replication directly. Such a role for Ap1 in HPV31 replication would be consistent with the function of the murine Ap1 homologue in polyomavirus DNA replication (26). Among all of the HPV31 mutants with defective factor binding sites that were analyzed, only the Oct1 site mutant replicated similarly to wt in transient and stable replication as well as DNA amplification. While binding of Oct1 to its cognate site in the URR may not be necessary for viral DNA replication or DNA amplification, it may still play a role in the modulation of differentiation-dependent late gene expression. Further studies using a minimal origin with added factor binding sites may be necessary to determine the exact mechanism by which specific cellular factors that bind to the URR modulate origin activity. Possible mechanisms include the alteration of chromatin structure, to produce nucleosome free regions on the viral minichromosome, or DNA looping, to provide contact between origin-proximal and -distal replication factors.

Adjacent to the KE is the AE domain, which contains multiple YY1 binding sites and E2BS1. In transient reporter assays, these YY1 sites have been shown to complement KE activation of early gene expression (14). Consistent with this role, our present findings also indicate that the AE moderately affects replication function directly. A previous study demonstrated that E2BS1 is required for transient and stable replication of HPV31 (33). This E2BS could also modulate replication by augmenting viral gene expression as has been shown for the related HPV18 (31).

Our analysis of HPV31 genomes which contained deletions in the 5′-URR domain demonstrated that these DNA sequences are not essential for transient and stable replication or differentiation-dependent DNA amplification. Interestingly, we found that the HPV31 mutant with a large 5′-URR deletion consistently replicated more efficiently than wt in transient assays and maintained a higher copy number in stable replication. One plausible explanation for the increased replication efficiency of pHPV31-d1140p is that the smaller plasmid size of this mutant (6,778 bp) could result in more favorable replication kinetics than for the wt DNA (7,912 bp). More likely, however, is the possibility that the 5′-URR domain modulates either E1 and E2 expression or replication directly. Previous studies with the low-risk mucosal HPV6 have identified negative regulatory sequences in this region which bind the CCAAT displacement factor (23). In transient reporter assays with HPV31, a similar element that weakly represses transcription from P97, the major viral early promoter, was found (14). In light of these transcriptional data, the results of our replication studies suggest that the 5′-URR domain down-modulates HPV31 DNA replication through different mechanisms. Recently, an attachment site for the nuclear matrix was mapped to the 5′-URR domain in the closely related HPV16 (34). Since we demonstrated that this region of the viral genome is not required in transient or stable replication of HPV31, our data suggest that attachment to the nuclear matrix as a mechanism for plasmid segregation may be facilitated through multiple redundant sites.

In this study, we have demonstrated the importance of URR sequences other than the minimal origin in regulating HPV31 plasmid replication in keratinocytes. The AE domain and the KE element can modulate replication in two ways: (i) indirectly through specific activation of E1 and E2 expression and (ii) directly through a yet unidentified mechanism. Both enhancer regions are required for transient and stable replication, while the 5′-URR domain or binding of Oct1 to the URR was nonessential for viral replication and DNA amplification. Independent of the type of mutation, HPV31 genomes which exhibited defects in either E1 and E2 gene expression or direct activation of replication replicated at low levels in transient assays and, invariably, were unable to replicate stably. Further dissection of the cis- and trans-acting components of the viral genome that regulate plasmid replication await the development of an efficient trans-complementing transfection system for HPVs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the Laimins laboratory for advice and helpful comments, and we thank R. Longnecker and K. Rundell for critically reading the manuscript.

W.G.H. is supported by INRSA grant F32-CA73087 from the National Cancer Institute. This work was supported by a grant from the NCI (CA74202) to L.A.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bedell M A, Hudson J B, Golub T R, Turyk M E, Hosken M, Wilbanks G D, Laimins L A. Amplification of human papillomavirus genomes in vitro is dependent on epithelial differentiation. J Virol. 1991;65:2254–2260. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2254-2260.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown T. Southern blotting. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. pp. 2.9.1–2.9.15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Vecchio A M, Romanczuk H, Howley P M, Baker C C. Transient replication of human papillomavirus DNAs. J Virol. 1992;66:5949–5958. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.5949-5958.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Villiers J, Schaffner W, Tyndall C, Lupton S, Kamen R. Polyoma virus DNA replication requires an enhancer. Nature. 1984;312:242–246. doi: 10.1038/312242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frattini M G, Laimins L A. The role of the E1 and E2 proteins in the replication of human papillomavirus type 31b. Virology. 1994;204:799–804. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frattini M G, Lim H B, Doorbar J, Laimins L A. Induction of human papillomavirus type 18 late gene expression and genomic amplification in organotypic cultures from transfected DNA templates. J Virol. 1997;71:7068–7072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7068-7072.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frattini M G, Lim H B, Laimins L A. In vitro synthesis of oncogenic human papillomaviruses requires episomal genomes for differentiation-dependent late expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3062–3067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldsborough M D, DiSilvestre D, Temple G F, Lorincz A T. Nucleotide sequence papillomavirus type 31: a cervical neoplasia-associated virus. Virology. 1989;171:306–311. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90545-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham F L, Davies J. Plasmid-encoded hygromycin B resistance: the sequence of hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene and its expression in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1983;25:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green H. Terminal differentiation of cultured human epidermal cells. Cell. 1977;11:405–416. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howley P M. Papillomavirinae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fundamental virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 947–978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hummel M, Hudson J B, Laimins L A. Differentiation-induced and constitutive transcription of human papillomavirus type 31b in cell lines containing viral episomes. J Virol. 1992;66:6070–6080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6070-6080.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanaya T, Kyo S, Laimins L A. The 5′ region of the human papillomavirus type 31 upstream regulatory region acts as an enhancer which augments viral early expression through the action of YY1. Virology. 1997;237:159–169. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klumpp D J, Stubenrauch F, Laimins L A. Differential effects of the splice acceptor at nucleotide 3295 of human papillomavirus type 31 on stable and transient viral replication. J Virol. 1997;71:8186–8194. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8186-8194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyo S, Klumpp D J, Inoue M, Kanaya T, Laimins L A. Expression of AP1 during cellular differentiation determines human papillomavirus E6/E7 expression in stratified epithelial cells. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:401–411. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-2-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyo S, Tam A, Laimins L A. Transcriptional activity of human papillomavirus type 31b enhancer is regulated through synergistic interaction of AP1 with two novel cellular factors. Virology. 1995;211:184–197. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCance D J, Kopan R, Fuchs E, Laimins L A. Human papillomavirus type 16 alters human epithelial cell differentiation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7169–7173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers C, Frattini M G, Hudson J B, Laimins L A. Biosynthesis of human papillomavirus from a continuous cell line upon epithelial differentiation. Science. 1992;257:971–973. doi: 10.1126/science.1323879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munger K, Phelps W C, Bubb V, Howley P M, Schlegel R. The E6 and E7 genes of the human papillomavirus type 16 together are necessary and sufficient for transformation of primary human keratinocytes. J Virol. 1989;63:4417–4421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4417-4421.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsson M, Osterlund M, Magnusson G. Analysis of polyomavirus enhancer-effect on DNA replication and early gene expression. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:479–483. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor M, Chan S-Y, Bernard H-U. Transcription factor binding sites in the long control region of genital HPVs. In: Meyers G, Delius H, Icenogle J, Bernard H-U, Baker C, Halpern A, Wheeler C, editors. Human papillomaviruses. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. pp. III-21–III-40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pattison S, Skalnik D G, Roman A. CCAAT displacement protein, a regulator of differentiation-specific gene expression, binds a negative regulatory element within the 5′ end of the human papillomavirus type 6 long control region. J Virol. 1997;71:2013–2022. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2013-2022.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piirsoo M, Ustav E, Mandel T, Stenlund A, Ustav M. Cis and trans requirements for stable episomal maintenance of the BPV-1 replicator. EMBO J. 1996;15:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rheinwald J G, Beckett M A. Tumorigenic keratinocyte lines requiring anchorage and fibroblast support cultures from human squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1981;41:1657–1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rochford R, Davis C T, Yoshimoto K K, Villarreal L P. Minimal subenhancer requirements for high-level polyomavirus DNA replication: a cell-specific synergy of PEA3 and PEA1 sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4996–5001. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruesch, M. N., and L. A. Laimins. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 28.Ruesch M N, Stubenrauch F, Laimins L A. Activation of papillomavirus late gene transcription and genome amplification upon differentiation in semisolid medium is coincident with expression of involucrin and transglutaminase but not keratin-10. J Virol. 1998;72:5016–5024. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5016-5024.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarver N, Byrne J C, Howley P M. Transformation and replication in mouse cells of a bovine papillomavirus—pML2 plasmid vector that can be rescued in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7147–7151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Southern P J, Berg P. Transformation of mammalian cells to antibiotic resistance with a bacterial gene under control of the SV40 early region promoter. J Mol Appl Genet. 1982;1:327–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steger G, Corbach S. Dose-dependent regulation of the early promoter of human papillomavirus type 18 by the viral E2 protein. J Virol. 1997;71:50–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.50-58.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stubenrauch F, Colbert A M, Laimins L A. Transactivation by the E2 protein of oncogenic human papillomavirus type 31 is not essential for early and late viral functions. J Virol. 1998;72:8115–8123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8115-8123.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stubenrauch F, Lim H B, Laimins L A. Differential requirements for conserved E2 binding sites in the life cycle of oncogenic human papillomavirus type 31. J Virol. 1998;72:1071–1077. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1071-1077.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan S H, Bartsch D, Schwarz E, Bernard H U. Nuclear matrix attachment regions of human papillomavirus type 16 point toward conservation of these genomic elements in all genital papillomaviruses. J Virol. 1998;72:3610–3622. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3610-3622.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, J., W. G. Hubert, and L. A. Laimins. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 36.Ustav M, Stenlund A. Transient replication of BPV-1 requires two viral polypeptides encoded by the E1 and E2 open reading frames. EMBO J. 1991;10:449–457. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vande Pol S B, Howley P M. The bovine papillomavirus constitutive enhancer is essential for viral transformation, DNA replication, and the maintenance of latency. J Virol. 1992;66:2346–2358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2346-2358.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in anogenital cancer as a model to understand the role of viruses in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4677–4681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]