Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is currently regarded as a systemic inflammatory disease with a growing burden of post-diagnosis associated comorbidities. To determine the initial burden of comorbiditis we evaluated the comorbidome at PsO onset.

Methods

In a matched case–control study, we extracted data on 57,228 patients and 125 morbidities from the Clalit Health Services Israeli insurance database. PsO cases were matched with control individuals by sex and age at enrolment. As pre-existing comorbidities, we considered all conditions already present in controls at the same age as the matched PsO case at the time of their diagnosis. To test for differences in the odds of comorbidities between the case and control groups, logistic regression analyses were run to calculate the odds ratio (OR) for each comorbidity, after which the comorbidome was graphically represented.

Results

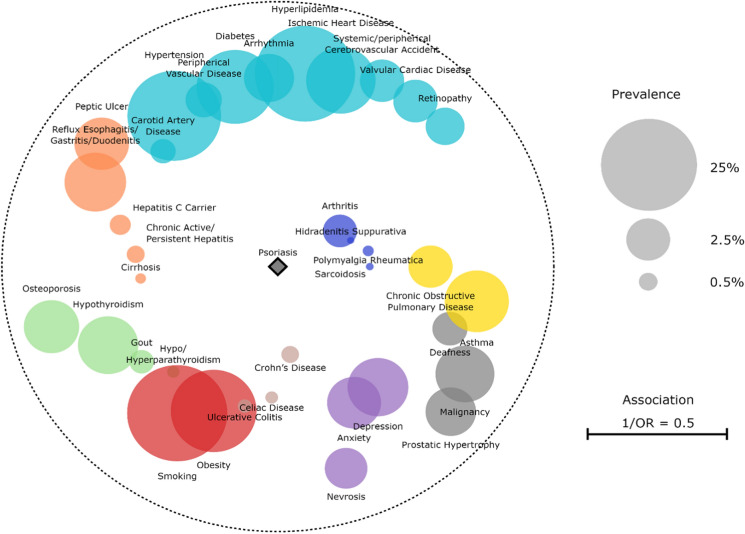

In this study we enrolled 28,614 PsO patients and 28,614 controls with an average age of 45.3 ± 19.6 years. At the time of diagnosis, PsO patients were more likely to be diagnosed with 2–4 comorbidities (28.8% vs 23.8%) and > 5 (19.6% vs 12.9%,). PsO patients’ specific comorbidomes evidenced several pathological cores: autoimmune and inflammatory systemic diseases [i.e., hidradenitis suppurativa (OR 3.55, 95% CI 1.88–7.28) or polymyalgia rheumatica (OR 3.01 95% CI 1.96–4.77)], inflammatory bowel diseases [i.e., Crohn’s disease (OR 2.99 95% CI 2.20–4.13)], pulmonary inflammatory diseases [i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR 1.81 95% CI 1.61–2.04)], hepatological diseases [i.e., cirrhosis (OR 2.00 95% CI 1.36–3.00)], endocrine diseases [dysthyroidisms (OR 1.82 95% CI 1.30–2.59)], mental disorders [i.e., depression (OR 1.72 95% CI 1.57–1.87)], and cardiovascular diseases (i.e., hypertension (OR 1.47 95% CI 1.41–1.53)].

Conclusion

The PsO-onset comorbidome may help health professionals plan more comprehensive patient management. By screening for these common PsO-linked conditions, early diagnosis and treatment may become more frequent, thus greatly benefiting patients on their medical journey.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Comorbidome, Precision medicine, Treatment, Systemic inflammation

Key Summary Points

| PsO (psoriasis) patients in the vast majority of the cases are multimorbid and clinicians have to treat a complicated patient that needs a multidisciplinary approach. |

| Unhealthy lifestyle habits are also frequent risk factors at the onset of PsO. |

| Identifying these factors can help physicians better treat patients and provide appropriate therapy. |

| Proper education of patients could develop their awareness of the comorbidities that interact with the disease, helping them to manage their condition. |

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is currently regarded as a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease [1] capable of causing several dermatologic and non-dermatologic comorbidities [2] that may influence its treatment and monitoring [2–4]. Our aging population and the spread of non-communicable diseases have made many of these comorbidities gain notoriety from a public health standpoint, due to their increasing prevalence. It is therefore important to study PsO-related multimorbidity in order to enable healthcare systems to address the growing complexities of our healthcare needs.

In a recent review by Bu and colleagues [5], the emergence of new PsO comorbidities (e.g., asthma, periodontitis, bullous diseases) was highlighted in relation to other associated pathologies (such as inflammatory bowel diseases, chronic kidney disease, and coronary artery disease). Understanding and monitoring such comorbidities, which is also known as the comorbidome, has become of paramount importance in order to choose the ideal biological therapy and customize follow-ups. Indeed, both epidemiological studies and murine models indicate that comorbidities may influence PsO progression and vice versa [6, 7]. Multidisciplinary styles and interdisciplinary teamwork are thus essential when treating people with multiple comorbidities, in order to properly manage their illnesses [8].

Although several scientific studies have analyzed the increased odds of specific comorbidities in psoriatic patients (providing possible etiological explanations for their association with PsO), epidemiological studies on the specific characteristics of the PsO comorbidome are still lacking. The aim of this research was to compare the pre-existing multimorbidity profile of psoriatic patients with that of non-psoriatic matched controls.

Methods

Clinical Data

This matched case–control study was conducted on 57,228 subjects, drawn from the Clalit Health Services Israeli database, recording all people registered to the insurance from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2017. All patients diagnosed with PsO at the time of recruitment (December 2017) were defined as a case group and a random selection of control subjects, without a diagnosis of PsO at the same time, (1:1), previously matched for sex (gender at birth) and age, were selected.

Clalit is the Israeli state’s largest health organization, charged with administering health services and funding its members. The database currently includes the healthcare records of 4.6 million patients collected over 14 hospitals and 1300 primary care clinics. Data collection captures demographic information (i.e., gender or date of birth) and diagnoses according to the methods previously described [9], including specific data related to these diagnoses. Differently from other dermatoses, PsO has its own label and its data extraction has been validated in the literature [10, 11].

Data on 125 comorbidities were also extracted from the same source, and were related to cardiovascular, endocrine, metabolic, gastrointestinal, hematologic, kidney, infection, mental health, musculoskeletal, nervous system, ocular, reproductive system, respiratory system, skin, rheumatic, autoimmune, and lifestyle related diseases and malignancies.

The current study focuses only on pre-existing comorbidities, considering all prevalent conditions that were present at the time of PsO onset. In controls, disorders that were present at the same age as when the matched psoriatic patients got their diagnosis were considered.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics on sex, age, and comorbidities were first obtained with categorical variables represented as frequencies. Means, medians, and standard deviation were applied to summarize continuous numerical variables (with SD).

The prevalence rates for each pre-existing morbidity were calculated as percentages together with their 95% binomial confidence intervals for proportions. Differences in comorbidity prevalence between case and control groups were then evaluated with a two proportion Z-test. Univariate logistic regression was performed to assess the odds ratio (OR) for each comorbidity in psoriatic subjects compared with non-psoriatic subjects. Results were considered statistically significant at 0.001, which takes into account the multiple tests performed.

The comorbidome was then plotted, graphically representing all comorbidities that had a statistically significant association with PsO onset (p < 0.001). The size of each bubble is proportional to the prevalence of the disease in the psoriatic cohort, while proximity to the center (psoriasis) expresses the strength of the association between the comorbidity and PsO diagnosis [this was numerically obtained as the inverse of the OR (1/OR)]. All circles relating to a disease with an increased occurrence in the psoriatic group fall inside the dashed orbit (1/OR < 1), while morbidities with a decreased prevalence are outside (1/OR > 1).

R 4.0.4 was used to conduct statistical analyses. Data preparation and visualization were performed in Python 3.8.8.

Ethical Approval Statement

The Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beersheba, Israel, approved this study and granted an exemption from informed consent.

Results

Demographic characteristics

PsO patients (N = 28,614) and controls (N = 28,614) were matched for age and gender. The mean age was 45.3 (SD ± 19.6) years, 50.5% of the subjects were male (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | PsO (N = 28,614) | Control (N = 28,614) | Total (N = 57,228) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value % | Value % | Value % | |

| Age | |||

| Mean ± SD | 45.30 ± 19.60 | 45.30 ± 19.60 | 45.30 ± 19.60 |

| Median (min–max) | 47.00 (0–97) | 47.00 (0–97) | 47.00 (0–97) |

| Sex | |||

| Male n (%) | 14,464 (50.50%) | 14,464 (50.50%) | 28,928 (50.50%) |

| Female n (%) | 14,150 (49.50%) | 14,150 (49.50%) | 28,300 (49.50%) |

| N. pre-existing morbidity | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.48 ± 3.01 | 1.81 ± 2.62 | 2.15 ± 2.84 |

| Median (min–max) | 1 (0–25) | 1 (0–23) | 1 (0–25) |

| N. pre-existing morbidity (classes) | |||

| 0 n (%) | 8980 (31.40%) | 12,232 (42.70%) | 21,212 (37.10%) |

| 1 n (%) | 5789 (20.20%) | 5890 (20.60%) | 11,679 (20.40%) |

| 2–4 n (%) | 8232 (28.80%) | 6797 (23.80%) | 15,029 (26.30%) |

| 5 + n (%) | 5613 (19.60%9 | 3695 (12.90%) | 9308 (16.30%) |

Table 2reports comorbidity prevalence in PsO patients and controls. The prevalence analysis revealed that, of those diagnosed with PsO, 28.70% (28.17–29.22) were smokers, 28.40% (27.87–28.92) already had hyperlipidemia, 22.10% (21.65–22.62) had hypertension, and 16.10% (15.70–16.55) were obese. Diabetes was also found to be one of the most frequent comorbidities in psoriatic patients, at 11.34% (10.98–11.72).

Table 2.

Pre-existing comorbidity prevalence rates and odd ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI) in psoriatic subjects compared to non-psoriatics

| Comorbidity | PsO (N = 28,614) | Control (N = 28,614) | OR* (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Prevalence % (95% CI) | n | Prevalence % (95% CI) | |||||

| Autoimmune and inflammatory systemic diseases | ||||||||

| Arthritis | 456 | 1.59 | (1.45; 1.75) | 121 | 0.42 | (0.35; 0.51) | 3.81 | (3.13; 4.68) |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | 39 | 0.14 | (0.10; 0.19) | 11 | 0.04 | (0.02; 0.07) | 3.55 | (1.88; 7.28) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 78 | 0.27 | (0.22; 0.34) | 26 | 0.09 | (0.06; 0.13) | 3.01 | (1.96; 4.77) |

| Sarcoidosis | 45 | 0.16 | (0.12; 0.21) | 15 | 0.05 | (0.03; 0.09) | 3.00 | (1.72; 5.57) |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | ||||||||

| Crohn’s disease | 155 | 0.54 | (0.46; 0.63) | 52 | 0.18 | (0.14; 0.24) | 2.99 | (2.20; 4.13) |

| Celiac disease | 95 | 0.33 | (0.27; 0.41) | 47 | 0.16 | (0.12; 0.22) | 2.03 | (1.44; 2.90) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 111 | 0.39 | (0.32; 0.47) | 60 | 0.21 | (0.16; 0.27) | 1.85 | (1.36; 2.55) |

| Pulmonary inflammatory diseases | ||||||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 772 | 2.70 | (2.51; 2.89) | 432 | 1.51 | (1.37; 1.66) | 1.81 | (1.61; 2.04) |

| Asthma | 1895 | 6.62 | (6.34; 6.92) | 1413 | 4.94 | (4.69; 5.20) | 1.37 | (1.27; 1.47) |

| Hepatological disease | ||||||||

| Cirrhosis | 74 | 0.26 | (0.20; 0.33) | 37 | 0.13 | (0.09; 0.18) | 2.00 | (1.36; 3.00) |

| Chronic active/persistent hepatitis | 160 | 0.56 | (0.48; 0.65) | 83 | 0.29 | (0.23; 0.36) | 1.93 | (1.49; 2.53) |

| Hepatitis C carrier | 202 | 0.71 | (0.61; 0.81) | 120 | 0.42 | (0.35; 0.50) | 1.69 | (1.35; 2.12) |

| Reflux esophagitis/gastritis/duodenitis | 1683 | 5.88 | (5.61; 6.16) | 1255 | 4.39 | (4.15; 4.63) | 1.36 | (1.26; 1.47) |

| Peptic ulcer | 1241 | 4.34 | (4.10; 4.58) | 988 | 3.45 | (3.24; 3.671) | 1.27 | (1.16; 1.38) |

| Endocrine diseases | ||||||||

| Hypo/hyperparathyroidism | 91 | 0.32 | (0.26; 0.39) | 50 | 0.18 | (0.13; 0.23) | 1.82 | (1.30; 2.59) |

| Hypothyroidism | 1599 | 5.59 | (5.33; 5.86) | 1111 | 3.88 | (3.66; 4.11) | 1.47 | (1.36; 1.59) |

| Gout | 258 | 0.90 | (0.80; 1.02) | 158 | 0.55 | (0.47; 0.65) | 1.64 | (1.35; 2.00) |

| Osteoporosis | 1293 | 4.52 | (4.28; 4.77) | 1107 | 3.87 | (3.65; 4.10) | 1.18 | (1.08; 1.28) |

| Mental disorders | ||||||||

| Depression | 1635 | 5.71 | (5.45; 5.99) | 974 | 3.4 | (3.20; 3.62) | 1.72 | (1.59; 1.87) |

| Anxiety | 1210 | 4.23 | (4.00; 4.47) | 718 | 2.51 | (2.33; 2.70) | 1.72 | (1.56; 1.89) |

| Neuroses | 715 | 2.5 | (2.32; 2.69) | 575 | 2.01 | (1.85; 2.18) | 1.25 | (1.12; 1.40) |

| Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases | ||||||||

| Carotid artery disease | 273 | 0.95 | (0.85; 1.07) | 165 | 0.58 | (0.49; 0.67) | 1.66 | (1.37; 2.02) |

| Hypertension | 6333 | 22.10 | (21.65; 22.62) | 4645 | 16.2 | (15.81; 16.67) | 1.47 | (1.41; 1.53) |

| Peripherical vascular disease | 519 | 1.81 | (1.66; 1.98) | 357 | 1.25 | (1.12; 1.38) | 1.46 | (1.28; 1.68) |

| Diabetes | 3247 | 11.40 | (10.98; 11.72) | 2339 | 8.17 | (7.86; 8.50) | 1.44 | (1.36; 1.52) |

| Arrhythmia | 1022 | 3.57 | (3.36; 3.79) | 736 | 2.57 | (2.39; 2.76) | 1.40 | (1.28; 1.55) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8124 | 28.40 | (27.87; 28.92) | 6455 | 22.60 | (22.08; 23.05) | 1.36 | (1.31; 1.41) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2355 | 8.23 | (7.91; 8.56) | 1778 | 6.21 | (5.94; 6.50) | 1.35 | (1.27; 1.44) |

| Systemic/peripherical cerebrovascular accident | 773 | 2.70 | (2.52; 2.90) | 619 | 2.16 | (2.00; 2.34) | 1.26 | (1.13; 1.40) |

| Valvular cardiac disease | 783 | 2.74 | (2.55; 2.93) | 629 | 2.20 | (2.03; 2.38) | 1.25 | (1.13; 1.39) |

| Retinopathy | 597 | 2.09 | (1.92; 2.26) | 482 | 1.68 | (1.54; 1.84) | 1.24 | (1.10; 1.40) |

| Environmental and lifestyle-related conditions | ||||||||

| Obesity | 4613 | 16.10 | (15.70; 16.55) | 2923 | 10.20 | (9.87; 10.57) | 1.69 | (1.61; 1.78) |

| Smoking | 8209 | 28.70 | (28.17; 29.22) | 6021 | 21.00 | (20.57; 21.52) | 1.51 | (1.45; 1.57) |

| Other | ||||||||

| Deafness | 487 | 1.70 | (1.56; 1.86) | 326 | 1.14 | (1.02; 1.27) | 1.50 | (1.31; 1.73) |

| Malignancy | 1515 | 5.30 | (5.04; 5.56) | 1209 | 4.23 | (3.99; 4.47) | 1.27 | (1.17; 1.37) |

| Prostatic hypertrophy | 1041 | 3.64 | (3.42; 3.86) | 871 | 3.04 | (2.85; 3.25) | 1.20 | (1.10; 1.32) |

*Reference control group, p-value < 0.001

Pathologies that were not statistically associated (p ≥ 0.001) with PsO were: oncology diseases (breast cancer, urine bladder cancer, kidney cancer, ovarian cancer, oral cancer, esophageal cancer, thyroid cancer, lung cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, liver cancer, chronic leukemia, melanoma, benign brain tumor, bone cancer, prostate cancer, cancer of genitalia, gastric cancer, laryngeal cancer, neck cancer, myeloma, sarcoma, neurofibromatosis, acute leukemia, polycythemia vera, lymphoproliferative cancer, colon cancer, myelodysplastic syndrome), chronic renal failure, aortic aneurism, irritable bowel syndrome, infertility, joint replacement, Behcet’s disease, chronic heart failure, hepatitis B carrier, muscular dystrophy, cardiomyopathy, hyperthyroidism, congenital anomalies, pemphigus vulgaris, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, familial Mediterranean fever, head of femur fracture, syphilis/gonorrhea, hereditary neurological disease, Parkinson’s disease, myasthenia gravis, dialysis, disability, tuberculosis, motor neuron disease, epilepsy, Wilson disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, glaucoma, scleroderma, psychoses, Gaucher disease, Addison’s disease, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, bronchiectasis, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, amyloidosis, idiopathic hypertrophic sub-aortic stenosis, hyperprolactinemia, pneumothorax, blindness, acromegaly, retinitis, pigmentosum, cystic fibrosis

The pathologies linked most strongly with PsO were arthritis (OR = 3.81, p < 0.001), hidradenitis suppurativa (OR = 3.55, p < 0.001), polymyalgia rheumatica (OR = 3.01, p < 0.001), sarcoidosis (OR = 3.00, p < 0.001), as well as Crohn’s disease (OR = 2.99, p < 0.001), celiac disease (OR = 2.03, p < 0.001), and cirrhosis (OR = 2.00, p < 0.001); these all had odds ratios ≥ 2.00.

These comorbidities are summarized as a graphical comorbidome (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

The PsO comorbidome. The size of each bubble is proportional to the prevalence of the disease. The proximity to the center expresses instead the strength of the association between the morbidity and the PsO diagnosis and is the inverse of the OR. The dashed orbit corresponds to a radius OR = 1. All circles relating to a disease with an increased occurrence among the psoriatic group fall inside that orbit (1/OR < 1); vice versa, morbidities with a decreased prevalence are outside (1/OR > 1)

Discussion

The present study indicates that the vast majority of psoriasis cases are multimorbid and thus, at the time of PsO diagnosis, clinicians are already having to treat a complicated patient needing a multidisciplinary approach. The conditions most associated with PsO onset were autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, hidradenitis suppurativa, polymyalgia rheumatica, sarcoidosis, and Crohn’s disease), followed by pulmonary inflammatory diseases and endocrine diseases. Looking at overall PsO, the most prevalent cluster of comorbidities included metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.

Previous research has already investigated the relationship between psoriasis and other systemic inflammatory diseases, highlighting the existence of a common pathogenic pathway in which chronic inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines play a significant role [12, 13] (as summarized in The Mosaic of Autoimmunity by Shoenfeld [14]). In line with the scientific literature, our data showed that a cluster of systemic inflammatory diseases (including arthritis, hidradenitis suppurativa, polymyalgia rheumatica, and sarcoidosis) had the strongest overall association with PsO. A quality study by Wu and colleagues [15] also confirmed this correlation, reporting an OR of 3.6 (95% CI [3.4–3.9]), which is close to the 3.81 found in our study. These inflammatory pathways may also be key in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). In a Danish study that compared patients with and without this disorder, patients with HS had an OR of 2.99 (95% CI [2.04–4.38]) of having PsO. The author found that both PsO and HS show increased levels of IL-12/23 and TNF-α, which are known important hallmarks of inflammation [16]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that psoriasis may share susceptibility genes with sarcoidosis due to the existence of polymorphisms in the IL23R gene [17, 18]. Since the TH1 and TH17 pathways are thought to play a role in many inflammatory cutaneous disorders (including psoriasis, sarcoidosis, and hidradenitis suppurativa), this association between PsO and HS may be explained by this common pathway [19, 20].

Inflammatory bowel diseases are also associated with PsO in situations such as Crohn’s disease. A previous review recognized that PsO is strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease because of genetic anomalies, immune dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and dysregulation of the gut microbiota [21]. Moreover, it has been reported that PsO and inflammatory bowel disease share genetic susceptibility loci on chromosome 6p21, which corresponds to PSORS1 in psoriasis and IBD3 in inflammatory bowel disease [22].

Our data also highlight a strong association between COPD and the onset of psoriasis. Similar to the other inflammation-related diseases previously discussed, findings by Wang and colleagues [23] confirm that patients with COPD (as well as those with psoriasis) exhibit an imbalance between T17 and Treg. Levels of IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and C-reactive protein (CRP) are highly elevated in COPD and are associated with the severity of the disease, a finding which is also seen in psoriasis [24]. Genetic susceptibility may also influence pulmonary-related diseases, with findings from previous research suggesting that loci for asthma and psoriasis may be partially overlapped [25–28]. Furthermore, the smoking habits of PsO patients, which are statistically higher than in the control group, could also directly trigger or worsen COPD, since PsO patients display subclinical airway inflammation [29].

Regarding liver diseases, the etiopathological link between these conditions and PsO is still not entirely clear, but a recent mouse model suggests a potential mutual influence in terms of flares [30]. It has also been previously reported that hepatic injury biomarkers and inflammatory biomarkers such as GM-CSF, iNOS, and ICAM-1 are increased in psoriatic inflammation [7]. Moreover, since PsO and hepatitis C virus (HCV) share pathophysiological factors, it is possible that the overproduction of TNF-α in HCV may trigger the onset of psoriasis [31]. Indeed, a study by Chun et al. [32] emphasized that patients with PsO and hepatitis C have higher levels of cutaneous inflammatory genes than patients with psoriasis alone. Compared with HCV-negative psoriatic patients, those with HCV infection have higher levels of cathelicidin, TLR9, and are IFNcofHCV-positive, suggesting that HCV infection may increase the risk of developing PsO.

Hypothyroid and parathyroid diseases were also found to be associated with PsO in our study, a finding that appears consistent with several previous studies. Indeed, one study showed that psoriatic patients have higher levels of thyroid peroxidase antibodies and thyroglobulin antibodies [33]. Psoriasis has also been successfully treated with propylthiouracil (an antithyroid preparation) on both the local [34] and systemic levels [35]. Other researchers found that patients with unbalanced thyroid function had a more severe form of PsO than those with euthyroid psoriasis. This may be due to direct or indirect effects of thyroid hormones on PsO, as well as the fact that excessive production of thyroid hormones could aggravate PsO due to their proliferation-promoting effects [36]. Similarly, there have been reported cases of generalized PsO associated with hypoparathyroidism, in which patients have benefited from calcium and vitamin D5 treatment [4, 37, 38]. These hormonal imbalances that influence the onset and development of psoriasis, although rare, have not yet been fully explained.

The association between PsO development and osteoporosis, although statistically significant, appears to be on the weak side in our cohort of patients. Limited studies have analyzed this association, and the results are controversial [18, 39]. Data from our study suggest that osteoporosis could be a facilitating factor for the development of PsO. Similarly, previous research has suggested that a lack of vitamin D (a vitamin which helps the body absorb calcium) could affect the development of PsO due to its impact on the immune chain as well as proliferative modulative effects [40, 41]. It should be noted that both psoriasis and osteoporosis have been proven to be associated with TNF-α and IL-6 dysregulation, as well as with metabolic syndrome [40, 42, 43]. These findings may suggest a common pathogenetic pathway underlying these two conditions.

Continuing further with this PsO/inflammation link, our data also suggest an association between PsO and mental disorders. Indeed, it has been found that a pre-existing diagnosis of major depressive disorder is a significant risk factor for the diagnosis of PsO [44]. One hypothesis is that a systemic inflammatory component is involved in the etiology of depression in both humans and mice. Proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin IL-1 and IL-6 are elevated in subjects with depression, suggesting that the inflammatory process contributes to these psychological comorbidities rather than psoriasis itself causing these disorders [45]. This means that psychiatric disorders may be triggered by PsO duration, where a state of systemic inflammation persists for a long time.

Similarly, both PsO and vascular disease are characterized by chronic inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines [46]. A number of pathogenic features shared by cardiovascular disease and PsO (including immunological processes, inflammation, and proinflammatory cytokines) contribute to the development of psoriatic lesions as well as to atherosclerotic plaques [47]. Triggered by local and systemic inflammatory cells as well as the release of proinflammatory cytokines, psoriatic lesions are a common symptom of PsO [48, 49].

Overall, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity emerged as the most frequent comorbidities among the psoriatic patients in our study. While these comorbidities are also classically associated with systemic inflammation, other possible links seem to be possible as well. In a Japanese study by Shiba et al., diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and myocardial infarction were more prevalent in patients that had psoriasis [50]. Another study showed that patients with cardiovascular disease who use beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have an increased risk of developing PsO (or to have a worsening of the disease) [51]. An association between PsO and the ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism (which is associated with a myriad of disorders, including diabetes and heart disease) was also observed in a case–control study [39].These studies indicate that there may be an indirect correlation between the use of drugs targeting these pathways and PsO onset.

Many of these metabolic issues are often related to lifestyle and environmental factors, some of which are also known risk factors for PsO onset [52]. Our data showed a very strong association between PsO and obesity, followed by smoking. Again, this can be traced back to inflammation — according to several studies, pro-inflammatory adipokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, leptin, and adiponectin secreted by adipose tissue contribute to the pathogenesis of PsO [3, 53]. Another prospective study on female nurses in the US confirmed that higher BMI and weight gain are risk factors for incident psoriasis [54]. Recent studies have also shown that obesity increases IL-17A, IL-22, and Reg3 in mice, possibly contributing to the occurrence of psoriasiform dermatitis [55], and that weight loss can be a possible method for reducing PsO severity in overweight individuals [56]. Similarly, common cytokine pathways may also explain the relationship between PsO and gout [57], where increased levels of Th1 and Th17 cytokines (as well as high serum levels of uric acid) were found in both PsO [58] and gout [59] patients. However, a convincing etiopathological explanation of the strong association between these two conditions has not yet been provided [57].

Other environmental factors can also contribute to PsO. Indeed, oxidative stress induced by air pollutants, including ultraviolet radiation, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, oxides, particulate matter, ozone, and cigarette smoke, have been identified as determinants of several human skin diseases [60]. Our study shows that approximately one out of four patients (28.7%) with PsO is a smoker. PsO is particularly common among heavy smokers as well as those who have smoked for a long time, according to a recent review and meta-analysis of 16 case–control studies [61]. A cross-sectional study in Italy also revealed that patients who smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day are twice as likely to present severe PsO compared with those who smoke less than ten cigarettes per day [62].

With regard to the association of malignancies (cancerous growths) with PsO, it has been hypothesized that immune check point inhibitors and molecular inhibitors may alter the immune system and, therefore, lead to the development of psoriasis [3]. Moreover, psoriasis can also be triggered by biologic drugs targeting tumor necrosis factor TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-23, or IL-17, through a paradoxical reaction that is thought to occur as a consequence of a cytokine imbalance caused by the blockage of immune signaling pathways [3]. Lastly, our study showed an association between deafness and PsO, suggesting that there may be a common pathogenetic pathway underlying these two diseases. To our knowledge, however, no previous scientific literature has investigated this hypothesis, leaving this as an area for future research. Another area of further investigation is a possible common pathway between prostatic hypertrophy and psoriasis, owing to recent scientific research showing that patients with prostatic hypertrophy could benefit from treatments with TNF-antagonists [63, 64].

Limitations and Strengths

Our study is based on an Israeli population that is split into Jewish and Arabic sub-populations, so future data will need to confirm our results in other patient subsets. Administrative data is usually collected for purposes other than research investigations, and thus could be less accurate than clinical data. Nevertheless, the use of such databases does have a major benefit, in that the use of routinely collected data minimizes the risk of selection bias, thus providing a useful insight into psoriasis in the general population.

Conclusion

Our current study describes the comorbidome found in PsO patients when they are first diagnosed with PsO. Psoriasis can be induced or exacerbated by a variety of factors, including genetics, comorbidities, and lifestyle. Identifying these factors can assist clinicians in better counselling patients about PsO, while simultaneously providing clues as to the pathogenesis of the disease. Due to the wide range of therapies associated with this comorbidome, all systemic PsO treatments should account for every individual’s ongoing drug prescriptions, lifestyle, and comorbidities. Lastly, by understanding the importance of major PsO comorbidities, while also being aware of their clinical interactions with PsO itself, patients could become active and well-informed participants in the management of their condition.

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

AB: conceptualization and design of the study, interpretation of results, critical revision of the article content. AM: writing and editing the manuscript. CC: preparation of figures and tables for publication, statistical analysis and modelling, data curation and management. ARB: data analysis. RLB: writing and editing the manuscript. SRM: literature review and background research. FNP: literature review and background research. KK: data collection, supervision. AC: data collection, supervision. GD: literature review and background research, critical revision of the article content.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The Human Investigation Committee of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beersheba, Israel, approved this study and granted an exemption from informed consent.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Data Availability

The authors declare that the data from their research is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Abstract book 17th World Congress on Public health Popul. Med. 2023; 5 (Supplement):A16 DOI: 10.18332/popmed/165253.

Arnon Dov Cohen and Giovanni Damiani have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Alessandra Buja, Email: alessandra.buja@unipd.it.

Giovanni Damiani, Email: giovanni.damiani1@unimi.it.

References

- 1.Damiani G, Bragazzi NL, Karimkhani Aksut C, et al. The Global, Regional, and National Burden of PsO: results and insights from the global burden of disease 2019 study. Front Med. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.743180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. PsO and comorbid diseases: Epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, et al. Risk factors for the development of PsO. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4347. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y, Nam Y-H, Lee J-H, et al. Hypocalcaemia-induced pustular PsO-like skin eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:591–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bu J, Ding R, Zhou L, et al. Epidemiology of PsO and comorbid diseases: a narrative review. Front Immunol. 2022;13:880201. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.880201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long S-Q, Fang J, Shu H-L, et al. Correlation of catecholamine content and clinical influencing factors in depression among PsO patients: a case-control study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2022;16:17. doi: 10.1186/s13030-022-00245-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadeem A, Ahmad SF, Al-Harbi NO, et al. IL-17A causes depression-like symptoms via NFκB and p38MAPK signaling pathways in mice: implications for PsO associated depression. Cytokine. 2017;97:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samarasekera E, Sawyer L, Parnham J, Smith CH. Guideline development group assessment and management of PsO summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2012;345:e6712. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.https://www.clalit.co.il. Accessed March 28th 2023 WWW Document]. URL https://www.clalit.co.il/he/Pages/default.aspx [accessed on 18 April 2023].

- 10.Kridin K, Ludwig RJ, Damiani G, Cohen AD. Increased risk of pemphigus among patients with PsO: a large-scale cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:1–4. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kridin K, Vanetik S, Damiani G, Cohen AD. Big data highlights the association between PsO and fibromyalgia: a population-based study. Immunol Res. 2020;68:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s12026-020-09135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehncke W-H, Schön MP. PsO. The Lancet. 2015;386:983–994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PsO YF. Comorbidities. J Dermatol. 2021;48:732–740. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahroum N, Elsalti A, Alwani A, et al. The mosaic of autoimmunity – finally discussing in person. The 13th International Congress on Autoimmunity (AUTO13) Athens. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;2022(21):103166. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2022.103166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon K-YT, Herrinton LJ. The association of PsO with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjærsgaard Andersen R, Saunte SK, Jemec GBE, Saunte DM. PsO as a comorbidity of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:216–220. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HS, Choi D, Lim LL, et al. Association of interleukin 23 receptor gene with sarcoidosis. Dis Markers. 2011;31:17–24. doi: 10.1155/2011/185106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy MJ, Leasure AC, Damsky W, Cohen JM. Association of sarcoidosis with PsO: a cross-sectional study in the All of Us research program. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s00403-022-02488-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanat KA, Schaffer A, Richardson V, et al. Sarcoidosis and PsO: a case series and review of the literature exploring co-incidence vs coincidence. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:848–852. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kridin K, Shani M, Schonmann Y, et al. PsO and hidradenitis suppurativa: a large-scale population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Y, Lee C-H, Chi C-C. Association of PsO with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1417–1423. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skroza N, Proietti I, Pampena R, et al. Correlations between PsO and inflammatory bowel diseases. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:983902. doi: 10.1155/2013/983902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Zhang C, Huang G, et al. Resveratrol inhibits dysfunction of dendritic cells from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients through promoting miR-34. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5145–5152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machado-Pinto J, dos Diniz M, Bavaso NC. PsO: new comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:8–14. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elder JT. Genome-wide Association Scan Yields New Insights into the Immunopathogenesis of PsO. Genes Immun. 2009;10:201–209. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weidinger S, Willis-Owen SAG, Kamatani Y, et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and PsO. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4841–4856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kere J. Mapping and identifying genes for asthma and PsO. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1551–1561. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Ke R, Shi W, et al. Association between PsO and asthma risk: a meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39:103–109. doi: 10.2500/aap.2018.39.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damiani G, Radaeli A, Olivini A, et al. Increased airway inflammation in patients with PsO. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:797–799. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Harbi NO, Nadeem A, Al-Harbi MM, et al. Psoriatic inflammation causes hepatic inflammation with concomitant dysregulation in hepatic metabolism via IL-17A/IL-17 receptor signaling in a murine model. Immunobiology. 2017;222:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imafuku S, Naito R, Nakayama J. Possible association of hepatitis C virus infection with late-onset PsO: a hospital-based observational study. J Dermatol. 2013;40:813–818. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chun K, Afshar M, Audish D, et al. Hepatitis C may enhance key amplifiers of PsO. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2017;31:672–678. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alidrisi HA, Hamdi KA, Mansour AA, et al. Is there any association between PsO and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis? Cureus. 2019 doi: 10.7759/cureus.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elias AN, Dangaran K, Barr RJ, et al. A controlled trial of topical propylthiouracil in the treatment of patients with PsO. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:455–458. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chowdhury MMU, Marks R. Oral propylthiouracil for the treatment of resistant plaque PsO. J Dermatol Treat. 2001;12:81–85. doi: 10.1080/095466301317085354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arican O, Bilgic K, Koc K. The effect of thyroid hormones in PsO vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aksoylar S, Aydinok Y, Serdaroğlu E, et al. HDR (hypoparathyroidism, sensorineural deafness, renal dysplasia) syndrome presenting with hypocalcemia-induced generalized PsO. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17:1031–1034. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2004.17.7.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vickers HR, Sneddon IB. PsO and hypoparathyroidism. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:419–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1963.tb13536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang Y, Wu W, Chen C, et al. Association between the insertion/deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene and risk for PsO in a Chinese population in Taiwan. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:642–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muñoz-Torres M, Aguado P, Daudén E, et al. Osteoporosis and PsO. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr Engl Ed. 2019;110:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kincse G, Bhattoa PH, Herédi E, et al. Vitamin D3 levels and bone mineral density in patients with PsO and/or psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatol. 2015;42:679–684. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wi D, Wilson A, Satgé F, Murrell DF. PsO and osteoporosis: a literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1438–1445. doi: 10.1111/ced.15174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Oliveira M, De FSP, De RB. PsO: classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:9–20. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y-H, Wang W-M, Li I-H, et al. Major depressive disorder increased risk of PsO: a propensity score matched cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blackstone B, Patel R, Bewley A. Assessing and improving psychological well-being in PsO: considerations for the clinician. PsO Targets Ther. 2022;12:25–33. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S328447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Späh F. Inflammation in atherosclerosis and PsO: common pathogenic mechanisms and the potential for an integrated treatment approach. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alexandroff AB, Pauriah M, Camp RDR, et al. More than skin deep: atherosclerosis as a systemic manifestation of PsO. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowes MA, Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Pathogenesis and therapy of PsO. Nature. 2007;445:866–873. doi: 10.1038/nature05663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grozdev I, Korman N, Tsankov N. PsO as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiba M, Kato T, Izumi T, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with PsO: a cross-sectional patient-population study in a Japanese hospital. J Cardiol. 2019;73:276–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering PsO: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roszkiewicz M, Dopytalska K, Szymańska E, et al. Environmental risk factors and epigenetic alternations in PsO. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2020;27:335–342. doi: 10.26444/aaem/112107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shibata S, Tada Y, Hau CS, et al. Adiponectin regulates psoriasiform skin inflammation by suppressing IL-17 production from γδ-T cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7687. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S, Han J, Li T, Qureshi AA. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change and the risk of PsO in US women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1293–1298. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanemaru K, Matsuyuki A, Nakamura Y, Fukami K. Obesity exacerbates imiquimod-induced PsO-like epidermal hyperplasia and interleukin-17 and interleukin-22 production in mice. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:436–442. doi: 10.1111/exd.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jensen P, Skov L. PsO and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633–639. doi: 10.1159/000455840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu SC-S, Lin C-L, Tu H-P. Association between PsO, psoriatic arthritis and gout: a nationwide population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:560–567. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, Bourcier M, Khalil S. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of PsO pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo G, Yi T, Zhang G, et al. Increased circulating Th22 cells in patients with acute gouty arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8329. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puri P, Nandar SK, Kathuria S, Ramesh V. Effects of air pollution on the skin: a review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:415. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.199579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou H, Wu R, Kong Y, et al. Impact of smoking on PsO risk and treatment efficacy: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:0300060520964024. doi: 10.1177/0300060520964024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Leffondré K, et al. Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of PsO. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1580–1584. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vickman RE, Aaron-Brooks L, Zhang R, et al. TNF is a potential therapeutic target to suppress prostatic inflammation and hyperplasia in autoimmune disease. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2133. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29719-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vickman RE, Aaron-Brooks L, Zhang R, et al. TNF blockade reduces prostatic hyperplasia and inflammation while limiting BPH diagnosis in patients with autoimmune disease. Cell Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.11.434972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data from their research is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.