Abstract

Purpose:

Disruptive behavioral disorders (DBDs) are common among children/adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. A 16-week manualized multiple family group (MFG) intervention called Amaka Amasanyufu designed to reduce DBDs among school-going children/adolescents in low-resource communities in Uganda was efficacious in reducing symptoms of poor mental health relative to usual care in the short-term (4 months post-intervention-initiation). We examined whether intervention effects are sustained 6 months postintervention.

Methods:

We used longitudinal data from 636 children positive for DBDs: (1) Control condition, 10 schools, n = 243; (2) MFG delivered via parent peers (MFG-PP), eight schools, n = 194 and; (3) MFG delivered via community healthcare workers (MFG-CHW), eight schools, n = 199 from the SMART Africa-Uganda study (2016–2022). All participants were blinded. We estimated three-level linear mixed-effects models and pairwise comparisons at 6 months postintervention and time-within-group effects to evaluate the impact on Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), impaired functioning, depressive symptoms, and self-concept.

Results:

At 6 months postintervention, children in MFG-PP and MFG-CHW groups had significantly lower means for ODD (mean difference [MD] = −1.08 and −1.35) impaired functioning (MD = −1.19 and −1.16), and depressive symptoms (MD = −1.06 and −0.83), than controls and higher means for self-concept (MD = 3.81 and 5.14). Most outcomes improved at 6 months compared to baseline. There were no differences between the two intervention groups.

Discussion:

The Amaka Amasanyufu intervention had sustained effects in reducing ODD, impaired functioning, and depressive symptoms and improving self-concept relative to usual care at 6 months postintervention. Our findings strengthen the evidence that the intervention effectively reduces DBDs and impaired functioning among young people in resource-limited settings and was sustained over time.

Keywords: Disruptive behavior disorders, Oppositional defiant disorder, Adolescents, Mental health, Sub-Saharan Africa, Multiple family groups, Randomized controlled trial, Intervention, SMART-Africa

Children and adolescents residing in low-resource communities in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) experience a considerable burden of mental health problems including depression, anxiety disorders, emotional and behavioral problems, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal behavior [1,2]. Emotional and behavioral problems are the most commonly reported (40.8%) across SSA countries [1,2], yet there is a paucity of mental health services [3], and culturally relevant effective evidence-based interventions available to reduce the burden of these conditions in youth populations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [3,4]. Failure to prevent and treat mental health problems in children and adolescents in low-resource communities has extensive unwanted societal consequences [5], and a substantial proportion of mental health problems are likely to continue into adulthood [6].

Risk factors contributing to the development of mental health problems in childhood and adolescence are highly prevalent in LMICs including SSA. For example, in Uganda, a SSA country with one of the largest youth populations in the world [7], many communities are heavily impacted by poverty and high levels of deprivation [8] (hence called low-resourced communities), HIV/AIDS [9,10], orphanhood [11], and exposure to violence and traumatic events [12]. Research shows young people in those communities (impacted by poverty, deprivation, and HIV/AIDS) have a higher prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems than the general adolescent population [2]. Hence, interventions that equip families to manage the multiple stressors in these low resourced and violence-exposed communities while simultaneously strengthening parent-child relationships are extremely important.

The Amaka Amasanyufu intervention is one such intervention that was implemented and tested among families with children and adolescents experiencing elevated symptoms of disruptive behavioral disorders (DBDs), and residing in low-resource communities in Uganda [4]. The Amaka Amasanyufu intervention showed positive short-term impacts on reducing Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODDs) [13], impaired functioning [13], and depressive symptoms, and significantly improved self-concept among children and adolescents with DBDs at the end of the 16-week intervention. We seek to examine whether these effects are sustained at least 6 months after the intervention ended (10 months postintervention initiation). Thus, this paper seeks to investigate the long-term (6-month postintervention) impact of the Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention on ODDs, impaired functioning, depressive symptoms and self-concept among children with DBDs in Uganda.

Methods

Study design and participants

The SMART-Africa Uganda scale-up study (2016–2022) tested a three-arm cluster-randomized controlled trial that was implemented in 26 public primary schools located within five districts of the greater Masaka region in Southwestern Uganda [4]. Schools were eligible for inclusion if their student population comprised between 350 and 600 students. A list of 42 eligible schools was created after school leadership expressed interest in participating during introductory meetings. From this list, 30 schools were randomly selected. Entire schools were randomly assigned using SPSS software by the research team to the following groups: (1) Control group comprising bolstered standard of care (BSOC) (n = 10 schools). The control group received literature on mental healthcare support usually provided to children with behavioral problems. This was bolstered with school notebooks and textbooks for all students enrolled in each of the three study groups; (2) Multiple Family Group delivered by parent peers (MFG-PP) (n = 10 schools); and (3) Multiple Family Group delivered by community healthcare workers (MFG-CHW) (n = 10 schools). Four schools (2 from each of the treatment groups [MFG-PP; and MFG-CHW]) were dropped because of COVID-19 lockdowns in the country, resulting in n = 8 schools for MFG-PP; and n = 8 schools for MFG-CHWs.

All participants were blinded. After randomization, within each school participants who met the following criteria were included: (1) child/adolescent aged 8 to 13 years in grades two to seven; (2) caregiver completed three screening measures for behavioral problems in children/adolescent (Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale [14]; Iowa Conners Scale [15]; and Impairment Rating Scale [16]); and (3) caregiver provided written consent and child/adolescent provided assent to participate. Children/adolescents were considered as having symptoms of disruptive behaviors if they scored positive on at least one of the screening measures. Further details are available in the study protocol [4]. Children/adolescents and caregivers completed assessments during the intervention (baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks) and at 6 months following the end of the intervention. Refer to Figure A1 for the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for phases of the cluster-randomized controlled trial.

Description of Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention

The Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention was designed to strengthen six key underlying principles. The 4Rs known as Rules, Responsibilities, Relationships and Respectful communication address parenting factors including family organization, discipline practices, family connectedness, support and communication. The 2Ss known as Stress and Social Support focuses on parenting stress and other life stressors and when and how to tap into support systems [4,17]. The intervention was designed to be delivered to groups of 6–20 multi-generational families (including caregivers/guardians, siblings, or other extended family members) per session [18]. Amaka Amasanyufu was culturally adapted from the ‘4Rs and 2Ss’ for the Ugandan context and delivered either by parent peer or community health worker facilitators over 16 sessions, promoting the use of task-shifting [17]. This is important since task-shifting is an approach used to improve delivery of mental health care in settings where shortages of trained health professionals exist as it shifts tasks from more highly trained providers to persons with less training (in this case, community healthcare workers and parent peers) [19].

The Amaka Amasanyufu intervention facilitated by either two parent peers or two community health workers was delivered in school settings. Sessions were normally held during breaks on school days and occasionally during weekends if the timing of the sessions conflicted with exams or other activities during that particular week. The sessions lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and consisted of group discussions, role plays, and other activities in order to facilitate support, learning, and interaction both within the family members and among the families in the group. Facilitator training was conducted separately for parent peers and community health workers. The training was delivered by team members that were trained by the study PI who developed the original intervention, and focused both on content and facilitation skills. To measure fidelity, the facilitators completed the Knowledge Skills and Attitude Test (KSAT) [20] to ensure that they mastered the content (a score of 85% or above was required). During intervention delivery, the trainers were present to observe all sessions and provided feedback to facilitators upon completion of each session.

Details on the theoretical frameworks guiding the cultural adaptation of the 4Rs and 2Ss to Amaka Amsanyufu can be found in the adaptation paper that has been previously published [17].

Ethics

The SMART Africa-Uganda study received ethical approval from the Washington University in St. Louis’s Institutional Review Board (#2016011088), the Uganda Virus Research Institute (GC/127/16/05/555), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (SS4090). The study procedures were also approved by the Data Safety and Monitoring Board at the National Institute of Mental Health. Written informed consent/assent were obtained from all study participants.

Outcomes

Four continuous outcomes were investigated, ODD and impaired functioning (from caregiver reports), and depressive symptoms, and self-concept (from child/adolescent reports). ODD was ascertained using the 5-items of the Iowa Conners rating sub-scale [15]. This scale measures the presence of oppositional-defiant rule-breaking behaviors in children/adolescents including mannerisms such as acts “smart”, temper outbursts, being defiant, and uncooperative. Each of the five items was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale. Caregivers were asked to rate their child’s behavior starting from 0 = not at all; 1 = Just a little; 2 = Pretty much; 3 = Very much. All five items were summed and analyzed as a continuous score. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.67, 0.74, 0.77, 0.79 corresponding to baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6 months postintervention. Impaired functioning was assessed using the six items of the Impairment Rating Scale by asking caregivers to rate their child’s behavior on a 6-point scale from 1 = no problem/does not need treatment/special services to 6 = extreme problem/definitely needs treatment/special services [16]. This scale assesses impaired functioning in six areas: (1) relationship with peers; (2) relationship with siblings; (3) relationship with parents; (4) academic progress; (5) self-esteem; and (6) overall family functioning. The summed total score was analyzed as a continuous variable. In the sample of adolescents who were positive for DBDs, this scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.54, 0.82, 0.79, 0.85 at each respective time point. Depressive symptoms was assessed using the 10-item Children’s Depression Inventory-short form (CDI:S) [21]. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.56, 0.66, 0.59, 0.61 for baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6 months postintervention. Children/adolescents’ perception about their identity, self-satisfaction, thoughts, and feelings about themselves, also known as Self-concept, was evaluated using the 20-item Tennessee Self-concept Scale [22]. This scale had a high Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73, 0.74, 0.75, 0.75 at baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6 months postintervention. Items were reverse coded where applicable and all items were summed to create a total summed score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptomatology or self-concept.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 17.0. At each time point, we summarized continuous outcomes within each group using means and standard deviations. We used multilevel (i.e., linear mixed effects) models to estimate and test the main effects for study group and time as well as the group-by-time interaction. For each outcome, we estimated a model comprising fixed categorical effects for study group (control, MFG-PP, and MFG-CHW), time (baseline; 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6 months postintervention), and their interaction; a random intercept for school; and unstructured correlations among subjects’ repeated measures. For all outcomes we conducted pairwise comparisons of post-baseline means using Sidak’s adjustment for multiple comparisons at 6 months only, since comparisons of postbaseline means at eight and 16 weeks have been reported in Brathwaite et al., [13]. We hypothesized that the MFG-PP and MFG-CHW group will have lower levels of ODD, impaired functioning, and depressive symptoms, and greater levels of self-concept compared to the Control group. We also hypothesized that the MFG-PP will perform better than the MFG-CHW group. Within each group, we assessed whether the means at 6-months post-intervention endpoint significantly differed from what was observed at the start of the intervention (time-within-group simple effects). We hypothesized that relative to the control group, both intervention groups would have significantly better outcomes at 6 months postintervention compared to baseline. After reporting baseline characteristics (Table 1), regression coefficients and associated test statistics for effects estimated by the main models are reported (Table 2) followed by the mean comparisons of interest comparing 6-month means to baseline means (Table 3). Both mean differences (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD) are reported. Only the 636 children and adolescents who screened positive for one of the DBDs during the screening phase were included in the analysis. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated to quantify the amount of correlation among observations within the same schools, and within participants within schools, since repeated measures were collected from the same participant four times.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and summary of outcomes among children/adolescents in each study group

| Characteristics | Control N = 243 |

MFG-PP N = 194 |

MFG-CHW N = 199 |

Total N = 636 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 10.9 (1.4) | 11.6 (1.3) | 11.8 (1.3) | 11.4 (1.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 112 (46.1) | 94 (48.5) | 102 (51.3) | 308 (48.3) |

| Female | 131 (53.9) | 100 (51.6) | 97 (48.7) | 328 (51.6) |

| Orphanhood status, n (%) | ||||

| Double orphan | 2 (0.8) | 4 (2.1) | 5 (2.5) | 11 (1.7) |

| Single orphan | 37 (15.3) | 24 (12.4) | 20 (10.1) | 81 (12.8) |

| Non-orphan | 203 (83.50) | 165 (85.5) | 168 (84.9) | 536 (84.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (3.0) | 8 (1.3) |

| Primary caregiver, n (%) | ||||

| Biological parents | 170 (70.0) | 123 (63.4) | 146 (73.4) | 439 (69.0) |

| Grandparents | 51 (21.0) | 47 (24.2) | 37 (18.6) | 135 (21.2) |

| Other relatives | 22 (9.1) | 24 (12.4) | 16 (8.1) | 62 (9.8) |

| ODD | 4.4 (3.1) | 3.8 (3.2) | 3.9 (3.0) | 4.1 (3.1) |

| Impaired functioning | 4.3 (1.4) | 4.2 (1.5) | 4.4 (1.5) | 4.3 (1.5) |

| Depressive symptoms | 3.4 (2.9) | 3.0 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.5) | 3.2 (2.7) |

| Self-concept | 73.0 (10.5) | 74.7 (10.8) | 73.9 (11.3) | 73.8 (10.8) |

Table 2.

Unstandardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for ODD, impaired functioning, depressive symptoms, and self-concept

| ODD |

Impaired functioning |

Depressive symptoms |

Self-concept |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | |

|

| ||||||||

| Time, χ2 (df) | 25.36 (3) | <.0001 | 1052.43 (3) | <.0001 | 118.44 (3) | <.0001 | 56.05 (3) | <.0001 |

| Baseline | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 8 weeks | −0.47 (−0.77, −0.17) | .002 | −2.02 (−2.20, −1.85) | <.001 | −0.01 (−0.37, 0.35) | .963 | −1.47 (−2.75, −0.19) | .025 |

| 16 weeks | −0.46 (−0.79, −0.13) | .006 | −1.85 (−2.16, −1.54) | <.001 | −0.34 (−0.64, −0.04) | .025 | 1.42 (0.06, 2.77) | .039 |

| 6 months | −0.28 (−0.79, 0.22) | .275 | −1.63 (−1.99, −1.28) | <.001 | −0.73 (−1.05, −0.40) | <.001 | 2.04 (0.75, 3.32) | .002 |

| Groups, χ2 (df) | 13.93 (2) | .0009 | 44.64 (2) | <.0001 | 22.30 (2) | <.0001 | 27.06 (2) | <.0001 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Parent peers | −0.47 (−1.17, 0.24) | .196 | −0.08 (−0.35, 0.19) | .561 | −0.39 (−0.79, 0.02) | .062 | 1.62 (−0.31, 3.56) | .100 |

| Community health workers | −0.45 (−1.47, 0.57) | .390 | −0.06 (−0.26, 0.39) | .708 | −0.27 (−0.76, 0.23) | .294 | 0.70 (−1.60, 3.00) | .549 |

| Time#groups, χ2 (df) | 7.877 (6) | .2480 | 47.08 (6) | <.0001 | 75.35 (6) | <.0001 | 30.59 (6) | <.0001 |

| 8 weeks#Parent peers | −0.07 (−0.74, 0.60) | .844 | −0.60 (−0.99, −0.21) | .002 | −0.26 (−0.88, 0.37) | .416 | 2.94 (0.45, 5.43) | .021 |

| 8 weeks#Community health workers | −0.36 (−1.29, 0.56) | .439 | −0.50 (−0.86, −0.13) | .008 | −0.71 (−1.34, −0.07) | .028 | 4.19 (2.05, 6.32) | <.001 |

| 16 weeks#Parent peers | −0.60 (−1.38, 0.17) | .129 | −1.11 (−1.67, −0.54) | <.001 | −0.25 (−0.94, 0.43) | .470 | 2.39 (0.14, 4.64) | .037 |

| 16 weeks#Community health workers | −0.63 (−1.47, 0.20) | .137 | −1.07 (−1.52, −0.62) | <.001 | −1.01 (−1.35, −0.67) | <.0001 | 3.98 (−0.66, 4.50) | .003 |

| 6 months#Parent peers | −0.52 (−1.19, 0.15) | .130 | −1.09 (−1.71, −0.47) | .001 | −0.62 (−1.13, −0.10) | .020 | 1.92 (−0.66, 4.50) | .1444 |

| 6 months#Community health workers | −0.84 (−2.02, 0.34) | .163 | −1.21 (−1.73, −0.70) | <.001 | −0.50 (−1.09, 0.09) | .097 | 4.36 (1.36, 7.37) | .004 |

| Constant | 4.33 (3.84, 4.82) | <.001 | 4.31 (4.13, 4.48) | <.001 | 3.40 (3.15, 3.65) | <.001 | 73.01 (72.27, 73.75) | <.001 |

| ICC (95% CI): schools | 0.02 (0.01, 0.06) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.07) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.06) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.07) | ||||

| ICC (95% CI): participant | 0.44 (0.40, 0.48) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.12) | 0.37 (0.33, 0.42) | 0.37 (0.33, 0.42) | ||||

| No. of participants | 636 | 636 | 630 | 630 | ||||

| No. of observations | 2,429 | 2,407 | 2,388 | 2,388 | ||||

Estimates reported above are fixed effects originating from a mixed effects model containing a random intercept for school and unstructured correlation among subjects’ repeated measures; Bolded numbers are significant.

CI = confidence interval; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; No. of observations = number of observations used in the regression analysis (across all timepoints); No. of participants = number of participants from whom data was used in the regression analysis.

Table 3.

Comparisons of means across time points within each group (time-within-group simple effects)

| Comparison across time | Study group | ODD |

Impaired functioning |

Depressive symptoms |

Self-concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast (95% CI) | Contrast (95% CI) | Contrast (95% CI) | Contrast (95% CI) | ||

|

| |||||

| 6 months versus baseline | Control | −0.28 (−0.96, 0.39) | −1.64 (−1.99, −1.28) | −0.73 (−1.05, −0.40) | 2.03 (0.75, 3.32) |

| MFG-PP | −0.80 (−1.39, −0.20) | −2.73 (−3.23, −2.22) | −134 (−1.75, −0.04) | 5.40 (3.12, 7.68) | |

| MFG-CHW | −1.12 (−2.55, 0.31) | −2.85 (−3.22, −2.47) | −1.23 (−1.73, −0.73) | 2.04 (0.75, 3.32) | |

| No. of participants | 636 | 636 | 630 | 630 | |

| No. of observations | 2,429 | 2,407 | 2,388 | 2,388 | |

Bolded numbers represent significant differences. Negative values indicate lower estimates at the follow-up time point compared to baseline, while positive values indicate higher estimates at the follow up time point compared to baseline within each group.

No. of observations = number of observations used in the regression analysis (across all timepoints); No. of participants = number of participants from whom data was used in the regression analysis.

Results

Description of sample

The description of the sample characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 1. The average age of children/adolescents was 11.4 years, and the majority were female (51.6%), not orphaned (84.3%), and cared for by biological parents (69.0%). The mean (SD) for ODD, impaired functioning, depressive symptoms, and self-concept at baseline by study group are also presented in Table 1. For the effects estimated in the main multilevel regression models, there were significant group-by-time interactions for all outcomes except ODD (Table 2).

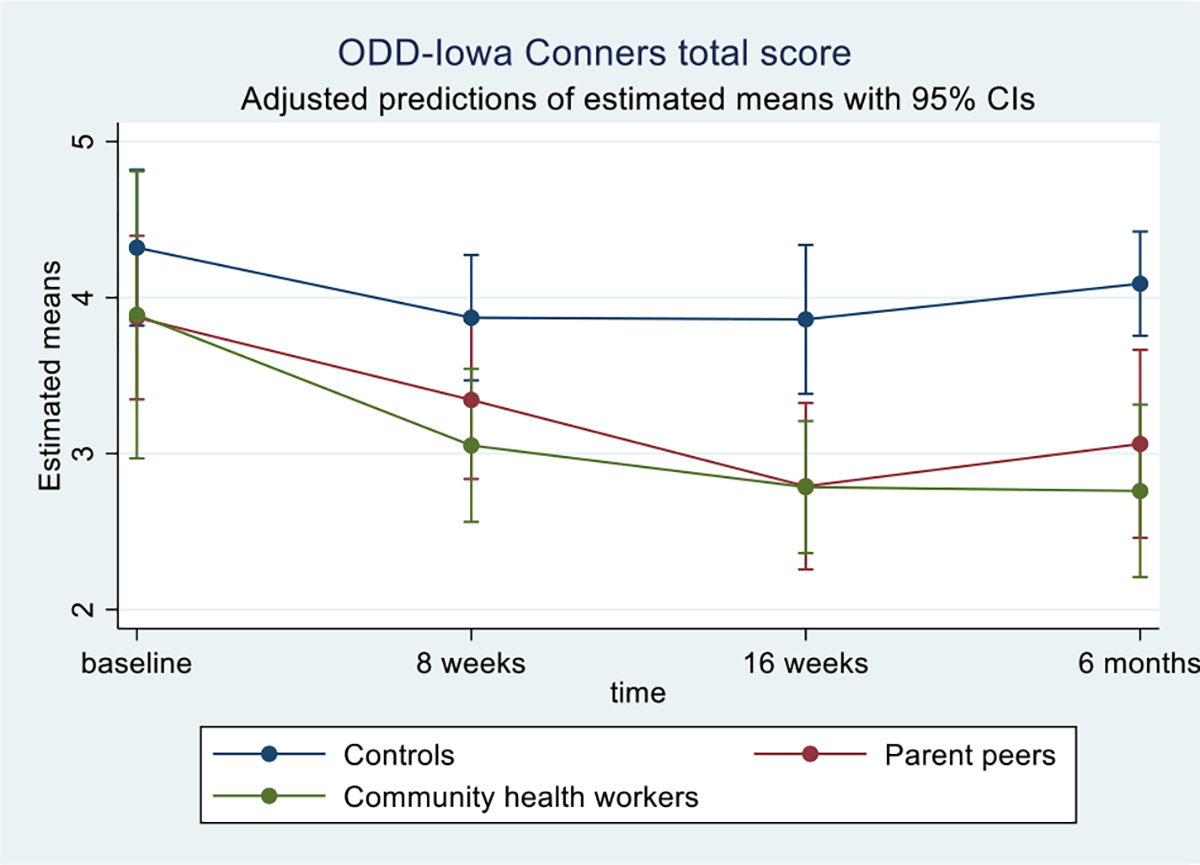

Group-within-time simple effects at 6 months postintervention

For ODD: At 6 months post-intervention, children in MFG-PP group had significantly lower mean scores on ODD than Controls, MD = −1.08, p = .002; SMD = −0.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.53, −0.13. Similarly, children/adolescents in MFG-CHW group had significantly lower mean scores on ODD, mean difference [MD] = −1.35, p < .001; SMD = −0.43, 95% CI −0.63, −0.24 than controls. However, there was no significant difference between the MFG-PP and MFG-CHW group MD = −0.28, p = .779; SMD = −0.09, 95% CI −0.30, 0.11 (MFG-CHW vs. MFG-PP) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted means for oppositional-defiant (OD) rule breaking behaviors as measured by Iowa Conners total score, by study group and time.

For Impaired functioning: At 6 months postintervention, children/adolescents in the MFG-PP group had significantly lower mean scores on Impaired functioning than Controls, MD = −1.19, p < .001; SMD = −0.57, 95% CI −0.77, −0.36. MFG-CHW also had lower scores than controls, MD = −1.16, p < .001; SMD = −0.55, 95% CI −0.75, −0.35. Therewas no difference between the MFG-PP and MFG-CHW, MD = 0.03, p = .999; SMD = 0.01, 95% CI −0.19, 0.22 (MFG-CHW vs. MFG-PP) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted means for impaired functioning as measured by Impairment Rating Scale total score, by study group and time.

For Depressive symptoms: MFG-PP had significantly lower scores than Controls, MD = −1.06, p < .001; SMD = −0.42, 95% CI −0.62, −0.22. MFG-CHW had lower scores than Controls, MD = −0.83, p = .002; SMD = −0.33, 95% CI −0.53, −0.13. There was no difference between MFG-PP and MFG-CHW groups, MD = 0.23, p = .740; SMD = 0.10; 95% CI −0.10, 0.31 (MFG-CHW vs. MFG-PP) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted means for depressive symptoms as measured by Children’s Depression Inventory total score, by study group and time.

For Self-concept: MFG-PP had higher self-concept scores than Controls, MD = 3.81, p = .003; SMD = 0.32, 95% CI 0.12, 0.52. MFG-CHW had significantly higher scores than Controls, MD = 5.14, p < .001; SMD = 0.44, 95% CI 0.24, 0.64. There was no difference between the two intervention arms, MD = 1.33, p = .616; SMD = 0.12; 95% CI −0.08, 0.33 (MFG-CHW vs. MFG-PP) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Adjusted means for self-concept as measured by Tennesse self-concept scale total score, by study group and time.

Time-within-group simple effects

For ODD, there was a significant reduction in mean scores at 6 months compared to baseline in the MFG-PP group but there was no significant difference between baseline and 6 months for MFG-CHW and Controls (Table 3). For Impaired functioning, depressive symptoms and self-concept, we observed significant changes in mean scores from baseline to 6-months across all study groups (Table 3). All groups had significantly higher mean self-concept scores at 6 months compared to baseline.

Discussion

We examined the impact of the Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention at 6 months following the end of the intervention on ODDs, impaired functioning, depressive symptoms and self-concept among children and adolescents who screened positive for DBDs in Uganda. The intervention was efficacious in reducing mental health problems among children and adolescents with DBD symptoms residing in low-income communities and environments that pose a high risk for the onset and perpetuation of mental health problems [8–12]. Compared to the control group, children and adolescents in the two intervention groups had significantly lower levels of ODD, impaired functioning, and depressive symptoms and greater self-concept that were sustained up to 6 months post intervention. However, there was no significant difference between the two intervention groups (MFG-CHW vs. MFG-PP). Comparisons of changes from baseline to 6 months postintervention revealed that all groups experienced improvements in impaired functioning, depressive symptoms, and self-concept outcomes at 6 months postintervention relative to baseline scores. However, for ODD, only children and adolescents in the MFG-PP group improved relative to baseline and there were no observable difference in ODD scores from baseline to 6 months for children and adolescents in the MFG-CHW and the control group.

The SMART Africa-Uganda study is the first to test the effect of the culturally adapted Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention that uses task-shifting approaches (mental health services being delivered by parents peers and/or community health workers instead of health care professionals) to address DBDs among children and adolescents in low-resource settings on a large scale, i.e., across 26 primary schools in Uganda. Children and adolescents in the control group received bolstered care comprising mental health support materials, school notebooks and textbooks. Although findings showed that children/adolescents in the control group benefited over time just by being in the intervention, their improvements were not comparable to the changes observed among children and adolescents in the two intervention groups.

The sustained effect of the Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention on reducing symptoms of poor mental health up to 6 months postintervention among participants in primary schools in Uganda aligns with findings reported in a systematic review of randomized controlled trials which evaluated the postintervention sustainability of the effect of mental health interventions among students in university settings across the world [23]. This review showed that symptom-reduction for combined mental illness health outcomes (which included anxiety, depression, psychological distress, fatigue, worry, sleeping problems, and perceived stress) was sustained up to 7–12 months postintervention, with symptom reduction for depression in particular extending up to 13–18 months postintervention [23]. Therefore, the sustained positive impact of the Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention 6 months after its end is encouraging and alludes to its potential to have longer-term impacts on child and adolescent mental health needs in Uganda and other SSA countries, where the burden of mental health problems is high but clinical resources are vastly limited. Hence, future studies should investigate the longer-term impact (beyond 6 months) on mental health symptom reduction in the Ugandan adolescent student population.

ODD is a known risk factor for the development of conduct disorder as well as subsequent onset of other psychiatric problems including anxiety and depression [24]. The demonstration of significant reductions in ODD symptoms that was sustained 6 months postintervention for children and adolescents in groups facilitated by parent peers (PPs) and community health workers (CHWs) are likely to translate into a range of individual, familial, and societal benefits in the long-term. Similarly, the significant sustained reduction in impaired functioning and improvement in children’s and adolescents’ relationship with siblings, peers, parents, family, as well as better academic performance, and self-esteem can drastically contribute to better mental health during young adulthood. Research shows that intervening early to improve family relationships during adolescence was associated with better mental health during adulthood and midlife [25]. Hence, the Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention’s beneficial impact on children and adolescents’ family relationships is likely to contribute to better mental health functioning later on in life.

Our findings should be considered in line with their limitations. Our sample was a young population (ages 8–13 years) who resided in rural communities in Uganda. Hence, we are unable to generalize our findings to older adolescents who may have higher rates of depressive symptoms and other psychiatric disorders [26,27], and to adolescents living in more urban areas. Furthermore, because we relied on self-reported data and the reported mental health conditions were not clinically diagnosed, there is a possibility that participants could have provided socially desirable responses. Additionally, the 6-month postintervention follow-up period is relatively medium term. We are unable to evaluate whether this intervention reduced or prevented onset of secondary disorders in late adolescence—longer term.

Given that the 16 session manualized intervention was relatively easy to administer and the MFG sessions were successfully facilitated by lay members of the community (parent peers and community health workers), this provides numerous innovative opportunities for scalability even in communities where clinically trained mental health staff are limited. The fact that there were no significant differences in child mental health outcomes at 6 months postintervention between the two intervention arms shows that both parent peers and community health workers can effectively deliver this intervention. This is particularly critical as it provides an opportunity to expand the lay workforce for the delivery of community-level mental health interventions to caregivers, especially in contexts where community health workers may already be overburdened. Moreover, in a separate study [28], we find that the cost of providing these task-shifted services is not cost prohibitive.

Conclusion

The Amaka Amasanyufu MFG intervention significantly reduced ODD, impaired functioning, and depressive symptoms and significantly improved self-concept compared to usual care among school-going children and adolescents with reported DBDs residing in low-resource communities in Uganda. The reported effects were sustained for at least 6 months postintervention. Our findings strengthen the evidence base for the Amaka Amansayufu MFG intervention being an effective intervention that can be utilized and potentially scaled up across other low-resource communities in SSA to reduce/prevent DBDs and simultaneously reduce the burden of poor mental health among children and adolescents.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

The culturally adapted MFG intervention significantly reduced symptoms of ODD, impaired functioning, and depressive symptoms and improved self-concept for children with DBDs in Uganda. This was sustained 6 months postintervention. The intervention has the potential to reduce the high burden of mental health problems among children and adolescents in SSA countries.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the 30 primary schools that agreed to participate in the study; Masaka Catholic Dioceses led, at the time of the study, by Rev. Fr. Bishop Baptist Kaggwa (RIP); Dr. Gertrude Nakigozi at RHSP; Dr. Apollo Kivumbi currently at Makerere University, Department of Psychiatry; Dr. Abel Mwebembezi at Reach The Youth-Uganda; parents and teachers who have contributed to the adaptation of the MFG content and delivery to the Uganda context; and all children and caregivers who agreed to be part of this study.

Funding Sources

The study outlined in this protocol is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) under Award Number U19 MH110001 (MPIs: Fred Ssewamala, PhD; Mary McKay, PhD). Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIMH award number R25 MH118935. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Clinical trials registry site and number: ClinicalTrials.gov, ID: NCT03081195.

Disclaimer: This article was published as part of a supplement supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. The opinions or views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funder.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.09.035.

References

- [1].Cortina MA, Sodha A, Fazel M, Ramchandani PG. Prevalence of child mental health problems in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jörns-Presentati A, Napp A-K, Dessauvagie AS, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents: A systematic review. PLoS One 2021;16:e0251689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011;378:1515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ssewamala FM, Sensoy Bahar O, McKay MM, et al. Strengthening mental health and research training in sub-Saharan Africa (SMART Africa): Uganda study protocol. Trials 2018;19:423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee S, Tsang A, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Mental disorders and termination of education in high-income and low- and middle-income countries: Epidemiological study. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Daumerie B, Madsen EL. The effects of a very young age structure in Uganda. Popul Action Int 2010:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- [8].World Bank Group. The Uganda poverty assessment report 2016. Farms, cities and good fortune: Assessing poverty reduction in Uganda from 2006 to 2013. The World Bank; 2016. Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Musumari PM, Techasrivichien T, Srithanaviboonchai K, et al. HIV epidemic in fishing communities in Uganda: A scoping review. PLoS One 2021;16:e0249465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].UNAIDS. Country factsheets Uganda 2020. HIV and AIDS estimates. 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda. Accessed December 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [11].United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF). Towards an AIDS-free generation - children and AIDS: Sixth stocktaking report, 2013. UNICEF; 2013. New York. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Naker D Violence against children: The voices of Ugandan children and adults. Kampala: Raising Voices/Save the Children; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Brathwaite R, Ssewamala F, Sensoy Bahar O, et al. The longitudinal impact of an evidence-based multiple family group intervention (Amaka Amasanyufu) on oppositional defiant disorder and impaired functioning among children in Uganda: Analysis of a cluster randomized trial from the SMART Africa-Uganda scale-up study (2016–2022). J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022;63:1252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pelham WE Jr, Fabiano GA, Massetti GM. Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2005;34:449–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Waschbusch DA, Willoughby MT. Parent and teacher ratings on the Iowa Conners rating scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2007;30:180. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, et al. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2006;35:369–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sensoy Bahar O, Byansi W, Kivumbi A, et al. From “4Rs and 2Ss” to “Amaka Amasanyufu” (happy families): Adapting a U.S.-based evidence-based intervention to the Uganda context. Fam Process 2020;59:1928–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff R, et al. Family-level impact of the CHAMP family program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Fam Process 2004;43:79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: A systematic review. J Rural Health 2018;34:48–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McKay M, Block M, Mellins C, et al. Adapting a family-based HIV prevention program for HIV-infected preadolescents and their families: Youth, families and health care providers coming together to address complex needs. Soc Work Ment Health 2007;5:355–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kovacs M Children’s depression inventory. A measure of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fitts WH, Warren WL. Tennessee self-concept scale, TSCS 2. Manual. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Winzer R, Lindberg L, Guldbrandsson K, Sidorchuk A. Effects of mental health interventions for students in higher education are sustainable over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ 2018;6:e4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Clark SE, Jerrott S. Effectiveness of day treatment for disruptive behaviour disorders: What is the long-term clinical outcome for children? J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;21:204–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen P, Harris KM. Association ofpositive family relationships with mental health Trajectories from adolescence to midlife. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:e193336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nalugya-Sserunjogi J, Rukundo GZ, Ovuga E, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression symptoms among school-going adolescents in Central Uganda. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2016;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nabunya P, Damulira C, Byansi W, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among high school adolescent girls in southern Uganda. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tozan Y, Capasso A, Namatovu P, et al. Costing of a multiple family group strengthening intervention (SMART-Africa) to improve child and adolescent behavioral health in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2022;106:1078–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.