Abstract

NMR spectra of 25 neat solvents have been recorded using No-D (no-deuterium proton) NMR, and water signals are visible in all spectra. Larger amounts of water can be measured by integration. Water can easily be detected at 0.01% (100 ppm), and amounts can be estimated by comparison with solvent 13C satellite peaks. Molecular sieves efficiently remove water from most solvents such that it cannot be detected by this NMR method. Additives in halogenated solvents and peroxides in ether and THF are also easily detected by No-D NMR.

Introduction

Water in organic solvents and the removal of this water has always been problematic. Standard methods of water removal include distillation from reactive drying agents1 and the use of molecular sieves.2 Many laboratories use commercial solvent purification systems that usually provide dry solvents. However, a classic problem that most chemists have encountered concerns an “old bottle of solvent”. How wet is this solvent? Should it be dried before using? Can it be used for a particular reaction? The answer to these questions can often be provided by using the “Gold Standard” for water determination in organic solvents, i.e., the Karl Fischer titration.3 However, many laboratories are not set up to routinely carry out Karl Fisher titrations, and this degree of accuracy is often unnecessary. An easy method for qualitatively determining water content in a variety of common organic solvents would be of value.4 Reported here is a simple and rapid No-D (no-deuterium proton) NMR method for detection of water in the organic solvents acetone, acetonitrile, benzene, tert-butyl alcohol, chloroform, dichloroethane, dichloromethane, diethyl ether, diglyme, dimethylacetamide, dimethylformamide, dimethyl sulfoxide, dioxane, ethyl acetate, ethanol, dimethoxyethane, methanol, methyl-tert-butyl ether, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, isopropyl alcohol, pyridine, tetrahydrofuran, toluene, triethylamine, and trifluoroethanol.

Results and Discussion

No-D NMR5,6 is a technique for running NMR spectra without using deuterated solvents. The major problem to be overcome with this technique is shimming the sample since there is no deuterium signal to lock on. Using a capillary tube containing a deuterated sample placed inside the undeuterated sample is one solution to the problem. Another method is to add a deuterated solvent (such as CDCl3 for locking and shimming) directly to the solvent being analyzed. However, this requires an additional step as well as meticulous drying of the deuterated solvent and these methods add complications that discourage using the technique. Another method is to gradient shim on the hydrogen (rather than deuterium) in the solvent signal. While this is easily done on some spectrometers, many are not set up with shimming on hydrogen as the default method. This obstacle could also discourage some from adopting the No-D technique.

The problem of shimming can be overcome very easily by preparing a sample of any deuterated solvent (CDCl3, CD3OD, etc.) using the same volume as the undeuterated solvent being analyzed. Note that any deuterated solvent will work for shimming. One needs to gradient shim the deuterated solvent7,8 and then replace the deuterated sample in the NMR probe with the undeuterated solvent sample to be analyzed. The shims for the two samples will be very similar as long as the volumes are the same. In fact, the spectra shown in this paper were recorded without any further shim adjustments on the undeuterated sample. The gain on the undeuterated solvent was lowered to avoid signal overloading of the spectrometer. The lock on the spectrometer was turned off,9 and the spectrum of the undeuterated solvent was recorded. The water signal can be easily identified, and the amount can often be determined by integration of this signal. In summary, recording the No-D NMR spectrum of a “wet” undeuterated solvent takes only a few minutes longer than a deuterated solvent. If one has access to a modern NMR spectrometer then semiquantitative water determination in organic solvents becomes quite easy.

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

Shown in Figure 1 is the No-D NMR spectrum of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from an old bottle found in the laboratory. The water signal can be clearly seen at δ 3.4 and is somewhat larger than the 13C satellite of the solvent signal. Integration of this signal indicates 0.9% water in the sample. Figure 2 shows the spectrum after drying with 3 Å molecular sieves. Water is not detectable by this NMR method.

Figure 1.

DMSO from a laboratory bottle.

Figure 2.

DMSO dried over 3 Å molecular sieves.

Table 1 gives the shift of the water signal in the 25 solvents studied. Spectra of all of these solvents containing water are also given as Supporting Information. The water shifts are quite solvent dependent, ranging from δ 4.9 for pyridine to δ 0.6 for toluene. They are also concentration dependent and move downfield as water becomes more concentrated. This has been previously noted,10 and indeed, a correlation exists between water concentration in acetonitrile and chemical shift. This was also observed for 5 other solvents. In fact, it has been suggested10 that water concentration can be determined from the water shift and the slope of the correlation line.

Table 1. Shifts of Water (0.1%) in Various Solvents.

| solvent | shift (ppm) | spectra |

|---|---|---|

| acetone | 2.9 | Figures S13–S15 |

| acetonitrile | 2.2 | Figures S31–S33 |

| benzene | 0.8 | Figures S34 and S35 |

| tert-butyl alcohol | 4.2 | Figure 6, Figure S30 |

| chloroform | 1.6 | Figures S27 and S28 |

| dichloroethane | 1.5 | Figures S37 and S38 |

| dichloromethane | 1.5 | Figures S25, S26, and S39 |

| diethyl ether | 2.3 | Figures 3–5, Figures S4–S6 |

| diglyme | 2.5 | Figures S40–S42 |

| dimethylacetamide | 3.6 | Figures S43–S45 |

| dimethylformamide | 3.5 | Figures S1–S3 |

| dimethyl sulfoxide | 3.4 | Figures 1 and 2 |

| dioxane | 2.6 | Figures S46–S48 |

| ethyl acetate | 2.5 | Figures S49 and S50 |

| ethanol | 3.9a | Figures S19 and S20 |

| glyme (DME) | 2.4 | Figures S51 and S52 |

| methanol | 3.9b | Figure 7, Figures S16–S18 |

| methyl-tert-butyl ether | 2.4 | Figures S53 and S54 |

| NMPc | 3.4 | Figures S29 and S30 |

| isopropyl alcohol | 4.0d | Figures S21 and S22 |

| pyridine | 4.9 | Figures S55 and S56 |

| tetrahydrofuran | 2.5 | Figure 6,Figures S8–S12 |

| toluene | 0.6 | Figures S57 and S58 |

| triethylamine | 3.2 | Figures S59–S62 |

| trifluoroethanol | 3.7e | Figures S23 and S24 |

In 50% DMSO.

In 67% DMSO.

N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone.

In 33% DMSO.

In 74% DMSO.

Dimethylformamide

Figure S1 shows the NMR spectrum of the very hygroscopic solvent dimethylformamide (DMF) from an old laboratory bottle. It contains a significant amount of water (3%) as evidenced by the large signal at δ 3.72. Molecular sieves are very effective at drying this solvent, as shown in Figure S2, where the amount of water was reduced to 0.03%. Storing this sample over molecular sieves for a day further reduced the water content to an undetectable level by this NMR method (Figure S3). Note that care must be taken to eliminate surface moisture on glassware and other sources of water, especially when using very hygroscopic solvents such as DMF and DMSO.

Diethyl Ether

The common laboratory solvent diethyl ether was next examined extensively. Figure 3 shows a sample that had been saturated with water and then extracted with a saturated NaCl solution, a common partial drying technique. The amount of water was 0.78% from integration of the water signal at δ 2.52. Adding anhydrous Na2SO4 to this solution for 15 min did not change the water concentration. Drying with a sample of old “anhydrous” MgSO4 lowered the water content to 0.44% (Figure S4). However, drying with fresh MgSO4 that had been heated to 250 °C under vacuum lowered the water content to 0.16% (Figure S5). It should be noted that a gastight syringe with a fixed fine-gauge needle was used to transfer all solvents used in this study to the NMR tube since it is quite easy to pick up small amounts of water from air when transferring volatile or hygroscopic solvents. Glove box techniques were not used. Shown in Figure 4 is a sample of ether containing 0.01% water (100 ppm) that was prepared by adding a known amount of 1.2% water in ether to a larger volume of completely anhydrous ether. The 0.01% water is clearly visible at δ 2.26. Finally, a spectrum of ether that has been dried using 3 Å molecular sieves shows no trace of water (Figure S6).

Figure 3.

Diethyl ether dried with saturated NaCl solution.

Figure 4.

Diethyl ether containing 0.01% water.

Practically speaking, what are the consequences of having 0.01% water in a solvent such as ether? We have found that Grignard formation from methyl iodide or bromobenzene and magnesium metal initiates readily using the ether shown in Figure 4 containing 0.01% water. Indeed, this amount of water is found in many commercial ether samples labeled as “anhydrous”. Although these small traces of water can be easily detected in commercial anhydrous ether by the current NMR method, these commercial solvents are quite good enough for formation of Grignard reagents without further treatment.

The presence of hydroperoxide 1 is a potential problem with diethyl ether. Figure 5 shows a spectrum of ether to which 0.5% of an independently prepared sample11 of hydroperoxide 1 has been added. Signals due to 1 can be easily identified at this concentration. Even at a concentration of 0.1%, hydroperoxide 1 can be readily observed by No-D NMR.

Figure 5.

Ether containing 0.5% hydroperoxide 1.

Tetrahydrofuran

One of the most important but problematic solvents in the organic chemist’s arsenal is tetrahydrofuran (THF). As with diethyl ether, important questions concern the presence of water as well as peroxides in THF. An authentic sample12 of this hydroperoxide 2 was also prepared. Figure S7 shows the spectrum of THF to which 0.5% hydroperoxide 2 has been added. Clearly, this hydroperoxide can be easily detected using the No-D NMR method.

How accurate is NMR integration for determining the amount of water in solvents? This was investigated using THF as solvent (Figures S8–S12). The problem involves integration of the small water peak in the presence of the large solvent signal. However, integration of the water peak is quite good for quantitative determination of water concentrations that are 1% or greater. Values are within 3% of values that are measured gravimetrically. As concentrations approach 0.1% water, the integration error increases and water concentrations are estimated to be ±10%. At concentrations below 0.1% water, integration error obviously increases and integration is not reliable. While water concentrations of 0.01% are easily detected (Figure S11), the exact amount cannot be determined by integration. While obviously not as good as a Karl Fischer titration, one should keep in mind that quantitative determination of small water concentrations is not the purpose of this NMR method. However, a number of solvents (shown in the Supporting Information) with about 0.01% water have been prepared by dilution of gravimetrically prepared more concentrated solutions. A comparison of the water signal height with solvent 13C satellite peak heights is useful for estimating water concentrations in this range.

Acetone

Figure S13 shows a spectrum of a commercial-grade acetone. Clearly visible is 0.3% water, as determined by integration. Figure S14 shows the attempt to dry this acetone using 3 Å molecular sieves. As previously reported,1 some dimerization via aldol self-addition to give diacetone alcohol can occur when drying acetone using molecular sieves. This condensation product is quite visible in the NMR spectrum. However, distillation readily removes the diacetone alcohol, giving dry acetone (Figure S15).

Alcohols

What about common alcohols that have acidic hydrogens that might rapidly exchange with the hydrogens of water and complicate NMR analysis of water content? As shown in Figure 6, the analysis of water in tert-butyl alcohol is not a problem. The exchange rate is slow enough such that the OH signal in a commercial sample of the alcohol is cleanly separated from the water signal.

Figure 6.

t-BuOH from a commercial source.

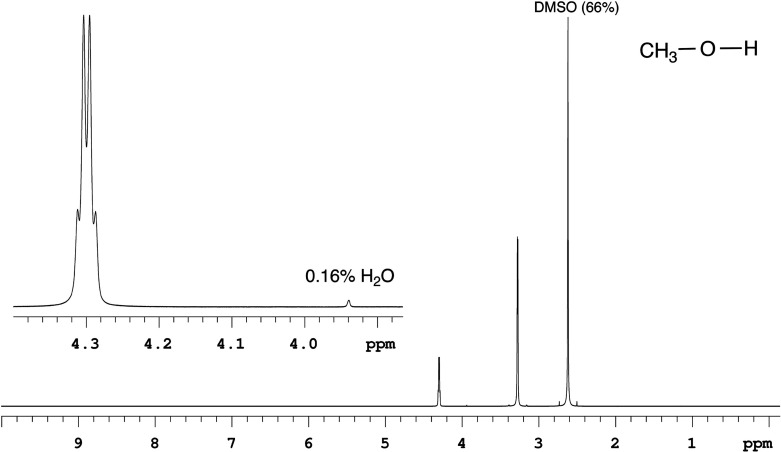

The spectrum of methanol indicates that exchange of the OH peak of this alcohol with water is a potential problem in determining the amount of water in this solvent. Figure 7 shows that this exchange can be slowed by using dry DMSO (66%) as a cosolvent. Here, the water present (0.16%) in laboratory-grade methanol can be clearly seen in the spectrum. Exchange is slow enough such that the coupling of the alcohol methyl group to the OH group can also be observed. Even when the amount of DMSO is reduced to 50%, the water signal in methanol is still discernible (Figure S16), although more rapid self-exchange among the methanol molecules removes the CH3/OH coupling. Molecular sieves (3 Å) are an effective but slow drying agent.2b However, the methanol must be distilled before NMR analysis using DMSO as a cosolvent (Figure S17). If the methanol is not distilled then the molecular sieves leave a contaminant that causes rapid exchange (even in dry DMSO) and prevents the observation of a water signal. The old method of drying methanol by refluxing with magnesium metal until the magnesium reacts and then distilling is also effective. Figure S18 shows methanol dried by this method. Note that it is necessary to distill the methanol twice since the initial distillation from magnesium leaves some trace impurity that leads to faster exchange and loss of CH3/OH coupling.

Figure 7.

Methanol with 66% DMSO cosolvent.

For analysis of water in ethanol, addition of 50% DMSO eliminates rapid exchange of the alcohol OH signal with water and permits facile determination of water content by integration of the distinct water signal (Figures S19 and S20). For analysis of isopropyl alcohol, 33% DMSO was used in the study (Figures S21 and S22). Even with the more acidic alcohol trifluoroethanol, using 74% DMSO as a solvent slows the exchange of the alcohol OH and the water so that the water signal is clearly observable at δ 3.7. While the exchange is not slow enough to observe coupling of the OH and the CH2 signals of the CF3CH2OH, it is slow enough to separate water from the alcohol OH signal (Figures S23 and S24).

Triethylamine

Figures S59–S62 show spectra of triethylamine containing various amounts of water. The water peak is somewhat broader than that in other solvents, but it is still quite discernible even at 0.1% and 0.05%. A sample of triethylamine that had been distilled (Figure S62) showed no detectable water peak. However, because the water peak is broader in triethylamine than that in other solvents, the No-D NMR method would not be able to detect water at the 0.01% level.

Additives in CH2Cl2 and HCCl3

A commercial sample of dichloromethane (Figure S25) revealed the presence of amylene, a preservative often added by suppliers as a stabilizer. Ethanol, added as a preservative, was easily detected in the spectrum of a sample of chloroform (Figure S27). The facile detection of such additives is of importance since it is not always obvious that they have been added to these commercial halogenated solvents. These additives can be easily removed by stirring with concentrated H2SO4 and distilling (Figures S26 and S28).

Exceptions

There are some notable examples where this No-D NMR method of detecting water is not completely successful. In the polar aprotic solvent N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, water is easily detected at greater than 1% (Figure S29). However, as the concentration of water drops and the signal moves upfield, the large CH2 signal at δ 3.39 begins to obscure the water signal. Therefore, while water can easily be detected at 0.1% (Figure S30), this method is not good for detecting water at much less than 0.1%. Use of dry DMSO as a cosolvent does not improve the resolution of the water signal at lower concentration.

Finally, detection of water in acetic acid was unsuccessful due to rapid exchange of the acidic hydrogen with the water signal. Addition of DMSO does not slow the exchange enough to allow separation of the two signals. Neither does use of pyridine as solvent.

Conclusions

No-D NMR is a practical and powerful way of detecting water and other additives in organic solvents. It provides an alternative when Karl Fischer titrations are unavailable or this level of accuracy is unnecessary. The most important item necessary to easily obtain well-shimmed spectra of neat undeuterated organic solvents is to use the same sample volume as a previously shimmed deuterated sample. Use of a nonspinning 3 mm NMR tube is also recommended in order to easily acquire optimally shimmed spectra.

Experimental Section

NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian DirectDrive 600 MHz spectrometer. Certain spectra were additionally recorded on a Bruker Avance III HD 500 MHz spectrometer. Spectra shown were recorded using 3 mm NMR tubes. In order to avoid spinning sidebands and artifacts, samples were not spun. NMR tubes were rinsed with acetone and anhydrous ether before being allowed to air dry. To remove surface moisture, the NMR tubes were then heated with a heat gun and flushed completely with nitrogen. Solvents were then introduced into the dry NMR tubes using a gastight 500 μL syringe with a fixed needle that had been dried in the same fashion as the NMR tube. Care was taken to fill the NMR tube to the exact height of the deuterated sample used for shimming (250 μL of solvent). When using 5 mm NMR tubes, if necessary, the Z1 and Z2 shims were manually adjusted for optimum field homogeneity after initial gradient shimming of a deuterated solvent.7 Most spectra were recorded using 16 transients with a 3 s relaxation delay.

The percent water (and percent peroxide) in solvents refers to weight percent. For example, a gravimetrically prepared solution of 1% water in THF (Figure S8) was prepared by adding 1980 mg of dry THF to 20 mg of water. Molar ratios of solvent to water can be calculated from appropriate integrals. These molar ratios were then converted to weight ratios in order to determine percent water in solvents. For example, the molar ratio of THF to H2O from the integrals in Figure S8 is 1000/4 to 20.2/2. This corresponds to 99% THF and 1.0% water by weight.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Professor Marvin J. Miller for helpful conversations and suggestions.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c00807.

Spectra of all of the solvents containing water (PDF)

FAIR data is available as Supporting Information and includes the primary NMR FID files for Figures 1–7 (1–7) and Figures S1–S29 (S1–S29). See FID for Publication for additional information (ZIP)

FAIR data is available as Supporting Information and includes the primary NMR FID files Figures S30–S62 (S30–S62). See FID for Publication for additional information (ZIP)

The author declares no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For leading references, see:; a Burfield D. R.; Lee K.-H.; Smithers R. H. Desiccant Efficiency in Solvent Drying. A Reappraisal by Application of a Novel Method for Solvent Water Assay. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 3060–3065. 10.1021/jo00438a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Burfield D. R.; Smithers R. H. Desiccant Efficiency in Solvent Drying. 3. Dipolar Aprotic Solvents. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 3966–3968. 10.1021/jo00414a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an historical perspective, see:; a Laszlo P. Two Laboratory Deaths, and Keeping Organic Solvents Dry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8822–8824. 10.1002/anie.201803276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Williams D. B. G.; Lawton M. Drying of Organic Solvents: Quantitative Evaluation of the Efficiency of Several Desiccants. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 8351–8354. 10.1021/jo101589h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fischer K. Neues Verfahren zur maßanalytischen Bestimmung des Wassergehaltes von Flüssigkeiten und festen Körpern. Angew. Chem. 1935, 48, 394–396. 10.1002/ange.19350482605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Meyer A. S.; Boyd C. M. Determination of Water by Titration with Coulometrically Generated Karl Fischer Reagent. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 215–219. 10.1021/ac60146a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Scholz E.Karl Fischer Titration; Springer: Berlin, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- For some recent methods of water determination, see:; a Sun H.; Wang B.; DiMagno S. G. A Method for Detecting Water in Organic Solvents. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4413–4416. 10.1021/ol8015429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu L.; Zhang Q.; Duan H.; Li C.; Lu Y. An ethanethiolate functionalized polythiophene as an optical probe for sensitive and fast detection of water content in organic solvents. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 3792–3798. 10.1039/D1AY00967B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kumar A.; Sahu M.; Maitra U. Water in Organic Solvents: Rapid Detection by a Terbium-based turn-off Luminescent Sensor. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1695–1699. 10.1002/ajoc.202100271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hoye T. R.; Eklov B. M.; Ryba T. D.; Voloshin M.; Yao L. J. No-D NMR (No-Deuterium Proton NMR) Spectroscopy: A Simple Yet Powerful Method for Analyzing Reaction and Reagent Solutions. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 953–956. 10.1021/ol049979+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hoye T. R.; Eklov B. M.; Voloshin M. No-D NMR Spectroscopy as a Convenient Method for Titering Organolithium (RLi), RMgX, and LDA Solutions. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2567–2570. 10.1021/ol049145r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gama L. A.; Merlo B. B.; Lacerda V. Jr; Romão W.; Neto A. C. No-deuterium proton NMR (No-D NMR): A simple, fast and powerful method for analysis of illegal drugs. Microchem. J. 2015, 118, 12–18. 10.1016/j.microc.2014.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creary X.; Jiang Z. A Simple Method for Determination of Solvolysis Rates by 1H NMR. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 5106–5108. 10.1021/jo00096a073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- In practice, a sealed sample of 250 μL of CD3OD in a 3 mm NMR tube is kept for shimming. Undeuterated solvents filled to this exact height in another 3 mm NMR tube work very well for NoD analyses. Samples in 3 mm NMR tubes usually require no further shim adjustments relative to the shimmed CD3OD sample. If one uses a 5 mm NMR tube then some minor manual adjustments of Z1 and Z2 shim settings may be necessary to obtain spectra of the quality shown in this paper. If sample volumes are slightly different from the deuterated shimming sample then peak symmetry and width can be degraded. However, when determining the amount of water present, relative integrals remain unchanged.

- A reviewer has suggested using excess NMR sample volumes such that they are outside of the probe coils but not exactly the same volume. In fact, when using 3 mm NMR tubes, this procedure gives reasonably well-shimmed spectra (but not quite as good as those presented in the Supporting Information) without needing to use exactly the same sample volumes. This shimming technique is not as successful when using 5 mm NMR tubes.

- Locking the spectrometer is unnecessary for most modern spectrometers since magnetic field drift is negligible during the few minutes needed to record spectra of typical solvents.

- Kang E.; Park H. R.; Yoon J.; Yu H.-Y.; Chang S.-K.; Kim B.; Choi K.; Ahn S. A simple method to determine the water content in organic solvents using the 1H NMR chemical shifts differences between water and solvent. Microchem. J. 2018, 138, 395–400. 10.1016/j.microc.2018.01.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milas N. A.; Peeler R. L. Jr; Mageli O. L. Organic Peroxides. XIX. α-Hydroperoxyethers and Related Peroxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 2322–2325. 10.1021/ja01638a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki Y.; Sakurai S.; Sakamoto R.; Matsumoto A.; Maruoka K. Iron-Catalyzed Radical Cleavage/C-C Bond Formation of Acetal-Derived Alkylsilyl Peroxides. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 573–576. 10.1002/asia.201901695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.