Abstract

We report a combined experimental and computational study of the mechanism of the Cu-catalyzed arylboronic acid iododeboronation reaction. A combination of structural and density functional theory (DFT) analyses has allowed determination of the identity of the reaction precatalyst with insight into each step of the catalytic cycle. Key findings include a rationale for ligand (phen) stoichiometry related to key turnover events—the ligand facilitates transmetalation via H-bonding to an organoboron boronate generated in situ and phen loss/gain is integral to the key oxidative events. These data provide a framework for understanding ligand effects on these key mechanistic processes, which underpin several classes of Cu-mediated oxidative coupling reactions.

Keywords: Cu-catalyzed iododeboronation, DFT analyses, Cu-mediated oxidative coupling reactions

Introduction

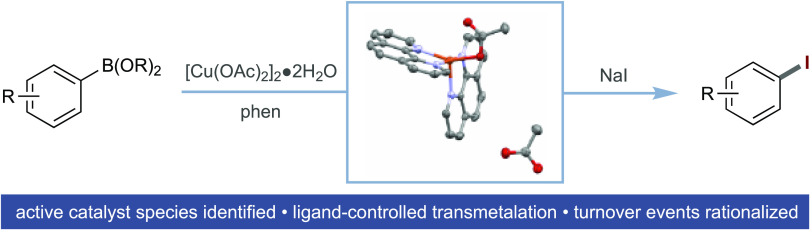

Cu-catalyzed iododeboronation of arylboronic acids using iodide is a useful reaction for the synthesis of aryl iodides (Scheme 1a).1−4 More importantly, this reaction accommodates iodide radioisotopes providing products that have important applications within in vivo imaging and radiotherapy.5−9

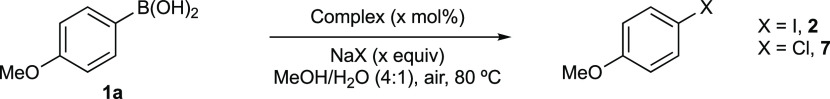

Scheme 1. (a) General Representation of Cu-Catalyzed Iododeboronation and (b) Tentative Description of the Iododeboronation Reaction9.

There are several reported methods for Cu-catalyzed iododeboronation, each with subtle variations in the copper source, ligand, and associated reaction conditions.1−4 Related copper-catalyzed or -mediated halodeboronation reactions, such as the equivalent fluorination reaction, also operate with similar reaction conditions.10−13 This general reaction class therefore has broad applications across synthetic chemistry and specific applications in bio-facing fields.

Very limited mechanistic information is available on the halodeboronation reaction in general, with a tentative mechanistic description of the iododeboronation largely based on the framework of the Chan–Lam reaction (Scheme 1b).9,14−18 This proposed mechanism involves transmetalation of the arylorganoboron compound to Cu(II), giving a Cu(II)(aryl) species, followed by disproportionation19 to Cu(III) and anion exchange/reductive elimination to give the aryl iodide product and Cu(I). Aerobic reoxidation of Cu(I) to Cu(II) closes the cycle.

Despite the importance and influence that ligand stereoelectronics exert on redox processes at metal centers, robust identification of intermediate ligand structures and speciation states remains a general problem in Cu-mediated oxidative catalysis. This renders the study of key mechanistic events, such as transmetalation, disproportionation, and oxidative turnover, difficult to understand and, therefore, control through rational catalyst design.

The main knowledge in this area arises from several key studies of catalytic reactions. Hartwig identified a Cu(III) intermediate in solution and proposed a mechanism for transmetalation of arylboronic acid pinacol (ArBpin) esters in a fluorodeboronation reaction using an F+ reagent, with ligands proposed for this key intermediate and event.11 Stahl,15,16 Watson,17,20 and Schaper21,22 proposed ligand sets for related Chan–Lam etherification and amination reactions, with broadly similar descriptions of rate-limiting transmetalation.23 Computational analysis of Chan–Lam amination reactions have aligned closely, although with some differences in the interpretation of the rate-limiting event.24 While being integral to many Cu-based oxidative coupling reactions, there is limited information on the disproportionation event or oxidative turnover.

Here, we report a detailed mechanistic description of the Cu-catalyzed iododeboronation reaction using a combination of structural, spectroscopic, and computational analyses. For the first time, this includes an assessment of ligand structures at all stages of the proposed catalytic cycle. More broadly, this analysis has provided insight into the transmetalation, disproportionation, and oxidative turnover events that underpin many Cu-mediated oxidative coupling reactions.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of Cu Complexes

For our analysis, we selected a catalytic iododeboronation system reported by Gouverneur using [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O and 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) as the catalyst/ligand system and NaI as the requisite source of iodide (Scheme 2).7 Based on these conditions, we sought to prepare complexes that may be formed in situ.

Scheme 2. Model Iododeboronation System Used in This Study.

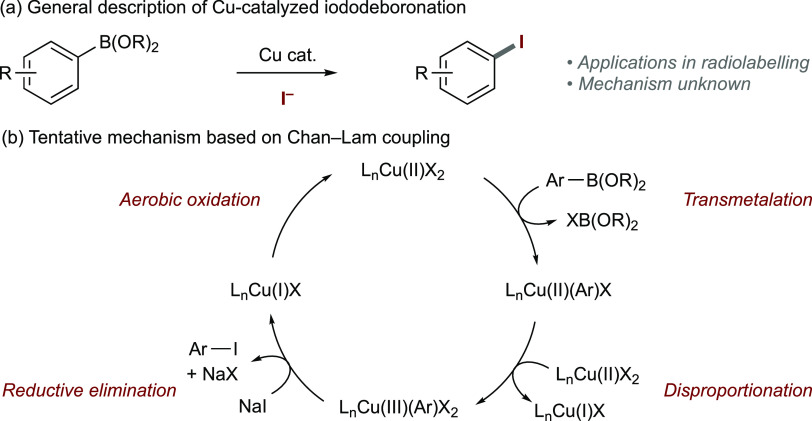

Treatment of [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O with phen delivered the monomeric complex [Cu(OAc)(phen)2]OAc ([3]OAc)25 or the dimeric complex [Cu(OAc)2(phen)]2·μ-H2O (4),26 following previous literature procedures (Scheme 3a). Recrystallization of [3]OAc in CH2Cl2 fortuitously led to the formation of [Cu(OAc)(phen)2]Cl ([3]Cl) (Scheme 3c). Treatment of [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O with phen under halodeboronation reaction conditions (NaI, MeOH/H2O) led to the formation of [Cu(I)(phen)2]I ([5]I) (Scheme 3d).27 A crystalline material from the reaction mixture of a completed iododeboronation reaction of 1a conducted under an inert atmosphere was isolated and determined to be the dimeric complex [Cu(μ-I)(phen)]2 (6) (Scheme 3e).28

Scheme 3. Formation of Cu Complexes 3–6.

Identification of Reaction-Relevant Cu Complexes

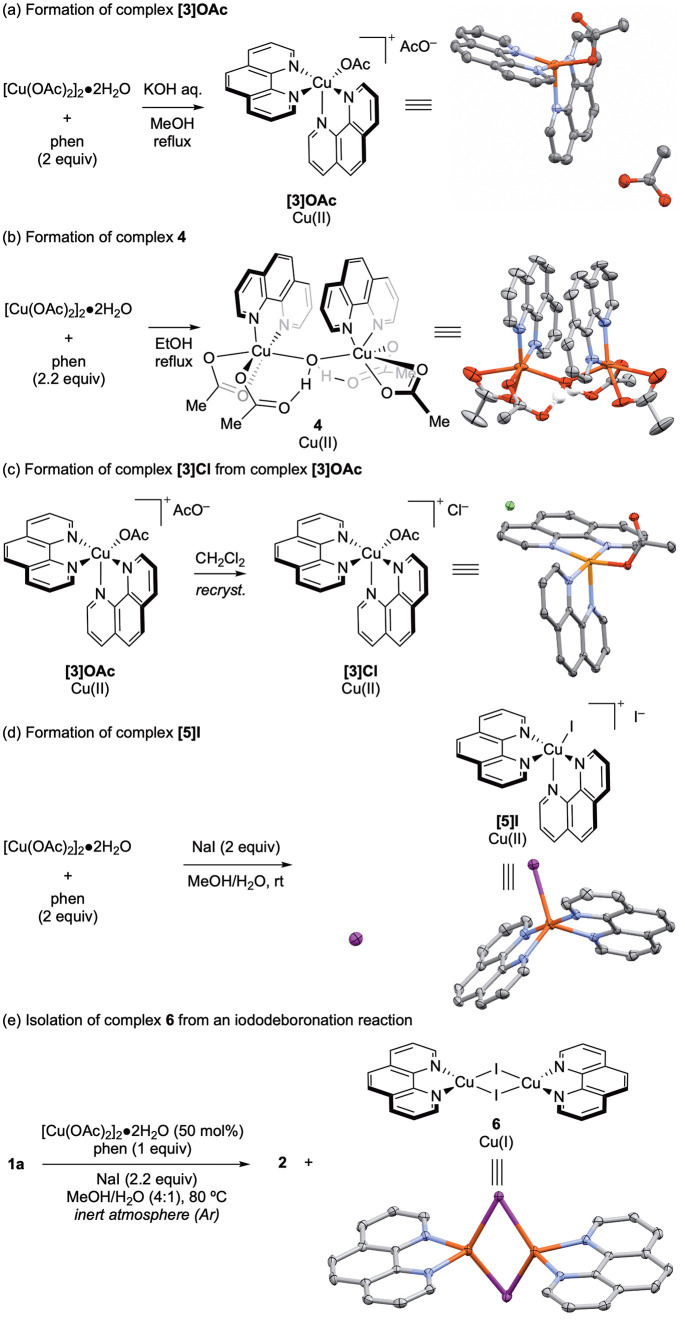

To elucidate the function of reaction components and identify reaction-relevant [Cu] + phen (2 equiv) Cu complexes, [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O was first treated with NaI; however, no reaction or denucleation of the paddlewheel was observed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (not shown, see Figure S13).

We therefore hypothesized that the reaction initiates by the formation of a Cu(II)(phen)n complex. Treatment of [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O with phen (2 equiv) and analysis by EPR spectroscopy showed the formation of a complex with a spectrum consistent with that of [3]OAc and less consistent with that of 4 (Figure 1). This suggested that [3]OAc was the dominant species arising from reaction-relevant Cu:phen stoichiometry (1:2).

Figure 1.

Overlaid EPR spectra for [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O (black), complex [3]OAc (blue), complex 4 (green), and the proposed in situ formation of a complex through complexation of [3]OAc by treatment of [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O with phen (2 equiv) (red). Solvent = MeOH/H2O (4:1). [Cu] = [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O.

Optimization of temperature and time was carried out, which allowed a range of complexes to be evaluated for catalytic performance (not shown, see SI Sections S2.2–S2.4). Using preformed [3]OAc or 4 in the iododeboronation reaction of 1a delivered the expected product 2, indicating reaction relevance and catalytic competency (Scheme 4); however, while [3]OAc exhibited catalytic turnover, 4 did not.

Scheme 4. Competency of [3]OAc and 4 in the Iododeboronation of 1a.

Yields determined by 1H NMR using an internal standard.

Note that to avoid complications in data analysis, 1a was used to avoid off-cycle inhibitory processes that are associated with release of pinacol from reactions using ArBpin (i.e., 1b; see SI Section S6).17 In addition, while it is possible to prepare Cu(II)(phen)3 complexes,29 these are not readily accessible under conditions relevant to the iododeboronation process and, as such, were discounted from this study.

Treatment of [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O with phen and NaI and analysis by EPR spectroscopy revealed a solution structure consistent with complexes [3]OAc and [3]Cl, with the observation of increased line broadening, which were significantly different to the spectrum of [5]I (Figure 2). Based on these data, we propose the formation of [3]I in situ, which subsequently proceeds to [5]I via further anionic ligand metathesis. Attempts to isolate [3]I were unsuccessful—all attempts led to isolation of [5]I.

Figure 2.

Overlaid EPR spectra for compound [3]OAc (black), complex 4 (red), complex [5]I (green), and the proposed in situ formation of [3]I through reaction of [Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O with phen (2 equiv), and NaI (2 equiv) (blue).

Use of complexes [3]Cl and [5]I in halodeboronation reactions was informative (Table 1). Stoichiometric [3]Cl delivered only 16% of the expected chloroarene product 7 while stoichiometric [5]I delivered quantitative conversion to 2 (entries 1 and 2). Similar effects were observed when using catalytic [3]Cl and [5]I in the presence of NaCl and NaI, respectively (entries 3 and 4): poor conversion was observed with [3]Cl but [5]I was competent. Interestingly, using NaI as the halide source, [3]Cl was catalytically competent and delivered exclusively the iododeboronation product 2 (7 not observed) despite the presence of 10 mol % chloride (entry 5). The reciprocal reaction using [5]I with NaCl delivered iododeboronation commensurate with the presence of 20 mol % iodide (from 10 mol % 5) as expected, but low levels of chlorodeboronation despite the presence of excess chloride (entry 6). These data suggest that (i) [3]Cl and [5]I are catalytically competent, (ii) complex [3]+ is likely a key on-cycle species and exists in equilibrium with, or is a precursor to, [5]+, and (iii) iodide transfer is more efficient than chloride. This latter point begins to impact upon understanding of halodeboronation in general, in particular aligning with the more difficult fluorodeboronation process.10−13

Table 1. Halodeboronation Competency and Halide Effect of Complexes [3]Cl and [5]I.

| entry | complex (loading) | NaX (equiv) | yield (product)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [3]Cl (1 equiv) | 16% (7) | |

| 2 | [5]I (1 equiv) | >99% (2) | |

| 3 | [3]Cl (10 mol %) | NaCl (2.2) | 20% (7) |

| 4 | [5]I (10 mol %) | NaI (2.2) | 83% (2) |

| 5 | [3]Cl (10 mol %) | NaI (2.2) | 67% (2) |

| 6 | [5]I (10 mol %) | NaCl (2.2) | 16% (2) |

| 17% (7) |

Yields determined by 1H NMR using an internal standard.

In situ reaction monitoring and sequential addition of reagents showed productive reactivity was only observed with the addition of NaI prior to 1a (not shown, see Figures S25 and S26). In addition, in the absence of NaI, low levels of side reactions were observed (ca. 18% in total, see Figure S27). Attempts to identify Cu(II)(aryl) complexes were unsuccessful. These observations were consistent with transmetalation being rate-limiting, as indicated through computational studies (vide infra), and for other reactions in this class, e.g., Chan–Lam processes.14 This suggested that the [Cu(II)(aryl)]+ complex can be intercepted by H2O or MeOH, with formation of minor side products. The effect of added I− could in principle arise from [3]I being able to undergo faster transmetalation than [3]OAc although this seems unlikely. Instead we propose that I– can competitively intercept the resulting [Cu(II)(aryl)]+ complex with the Cu(II)(aryl)(I) complex being more favorable for the subsequent mechanistic event. This last possibility is borne out by our computational studies.

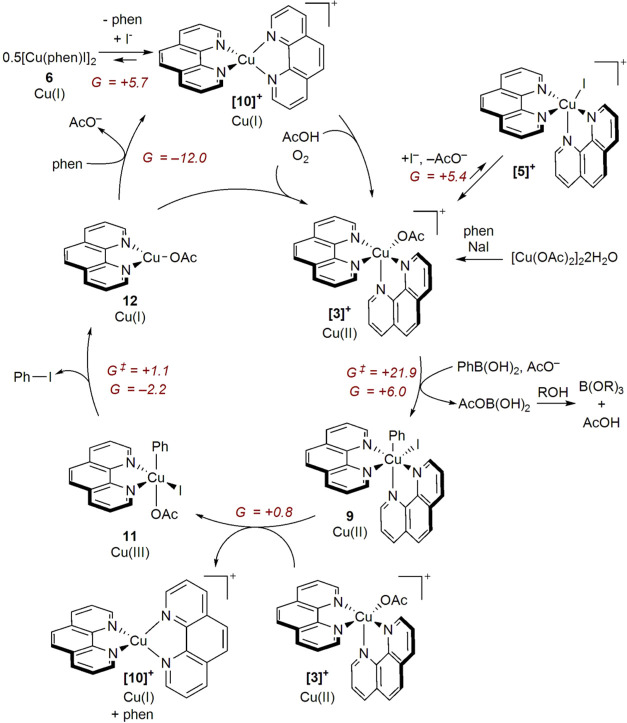

We hypothesized that Cu(I) complex 6 was produced following reductive elimination of the product from a Cu(III) intermediate. This complex was notable due to the 1:1 Cu:phen ratio, which implied loss of one phen ligand from the proposed intermediate [3]+. To enable catalysis, 6 would require oxidation to Cu(II) in the presence of air (the terminal oxidant used in the iododeboronation process). Oxidation of CuOAc under air was therefore monitored by ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis spectroscopy) (Figure 3a) and in the presence of other reaction-relevant additives. Oxidation was not observed in air or in the presence of NaOAc or substrate 1a. B(OH)3, which has been effective in promoting oxidation in Chan–Lam amination reactions, also had no effect;17 however, addition of phen (Cu:phen = 1:2) and AcOH was effective at promoting the oxidation. The effect of AcOH is consistent with previous observations in Chan–Lam reactions.15−17 The dependence on a Cu:phen ratio of 1:2 for catalyst turnover was shown by the direct use of 10 mol % 4, when a yield of 6% was obtained. Further investigation using stoichiometric 4 under an inert atmosphere resulted in a 51% yield, confirming reactivity, with catalytic turnover limited by an inability to undergo reoxidation. When an additional equivalent of phen was included (with respect to Cu loading), this enabled catalytic turnover, resulting in a 70% yield (Table S5). The effect of phen stoichiometry on oxidation was notable: oxidation of [Cu(phen)I] required an 18 h reflux, compared to [Cu(phen)2I], where oxidation was achieved within 20 mins at 70 °C.30 Heating to a minimum of 30 °C was also required for oxidation to occur (Figure S10), with a reaction yield of 9% (i.e., one catalytic cycle at 10 mol % catalyst) at room temperature and 70% at 30 °C (Table S2). Moreover, the EPR spectrum of the oxidation in the presence of phen was consistent with that of the proposed [3]I (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Oxidation of CuOAc in air and in the absence/presence of reaction components. (b) EPR spectra of oxidation of CuOAc + phen/NaI under air.

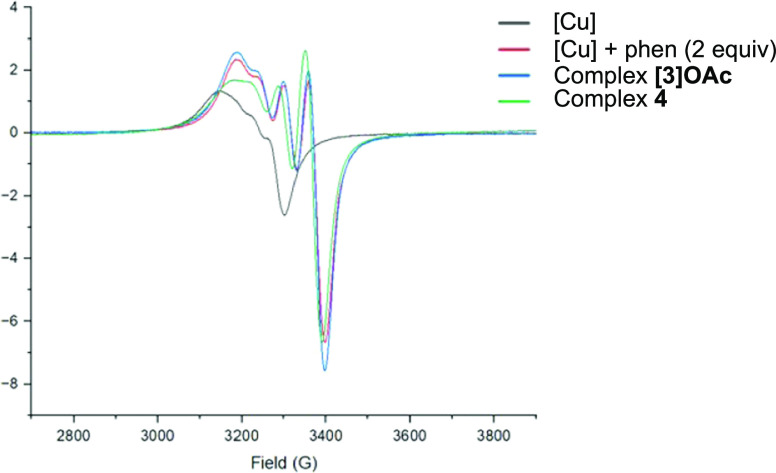

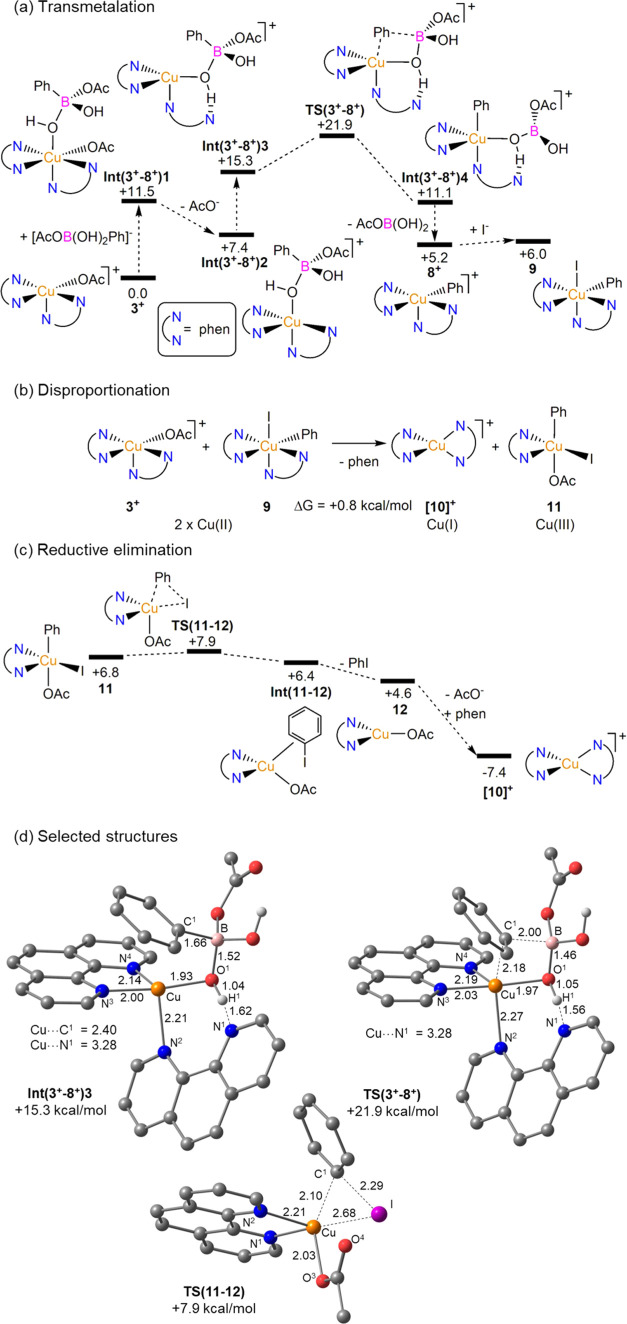

The above data indicated that ligand speciation, specifically relating to phen stoichiometry, varied during the reaction and Cu required one or two phen for specific mechanistic events. To shed more light on this issue and to clarify the details of the iododeboronation reaction mechanism, we turned to DFT calculations (Figure 4).31

Figure 4.

Computed reaction profiles (free energies, kcal/mol) for (a) the transmetalation step linking [3]+ to [8]+ and 9 with AcO– as a base, (b) disproportionation of Cu(II) intermediates [3]+ and 9, and (c) reductive elimination from Cu(III) intermediate 11. (d) Selected computed geometries with key distances in Å and nonhydroxy H atoms are omitted for clarity. See SI Section 8 for alternative pathways considered.

The geometry computed in solution for the [Cu(phen)2OAc]+ cation, [3]+, displays a distorted square-pyramidal geometry (τ = 0.2832) with an axial N-donor and a κ1-OAc ligand (Cu–O distances = 2.01 Å/2.70 Å), similar to the cation in the solid-state structure of [3]OAc (τ = 0.42, Cu–O = 2.00/2.64 Å25). A variety of alternative precursor species were also assessed: 6-coordinate Cu(phen)2(OAc)x(X)2–x (X = I, OAc; x = 0–2), cationic [Cu(phen)2(X)(S)]+ (S = MeOH, H2O), and mono-phen 4-coordinate Cu(phen)(OAc)x(I)2–x (see Tables S6 and S7). Of these, the most accessible was Cu(phen)(OAc)2 (ΔG = +3.1 kcal/mol), while OAc/I exchange in [3]+ to give 5-coordinate [Cu(phen)2I]+ ([5]+) was endergonic by 5.4 kcal/mol. The computed geometry of [5]+ is trigonal bipyramidal (τ = 0.90) in good agreement with the solid-state structure of [5]I (τ = 0.85). Similar speciation studies identified [Cu(phen)2Ph]+, [8]+, as the most stable Cu-aryl intermediate formed upon transmetalation (where Ph was used as the prototypical aryl group). [8]+ exhibits a distorted square-pyramidal geometry with an axial N-donor (τ = 0.37). Cu(phen)2(I)Ph, 9, lies only 0.8 kcal/mol above [8]+, suggesting that it would be readily accessible in solution. Loss of a phen ligand from 9 to form Cu(phen)(I)(Ph) is disfavored (ΔG = +7.5 kcal/mol).

Having identified [3]+ and [8]+ as the most likely precursor and intermediate formed in the transmetalation step, we turned to the details of that process. The most accessible computed profile is shown in Figure 4a, where the acetate present in solution engages 1a to deliver the cognate boronate.33 This first binds to [3]+ via a hydroxyl substituent to give Int(3+-8+)1 at +11.5 kcal/mol. Dissociation of the Cu-bound acetate ligand then forms Int(3+-8+)2 (+7.4 kcal/mol) from which the Cu–N1 phen arm decoordinates to form Int(3+-8+)3 (+15.3 kcal/mol), which features a strong H-bond with the Cu-bound OH of the boronate (N1···H1 = 1.62 Å, see also Figure 4d for the computed structure and atom labeling). This places the Ph group adjacent to a vacant site at Cu (Cu···C1 = 2.40 Å) from which Ph group transfer can readily occur via TS(3+-8+) with an additional barrier of only 6.6 kcal/mol. All Cu–N bonds lengthen slightly in this transition state to accommodate the transferring phenyl group, while the N1···H1 shortens further to 1.56 Å. The initial Cu–phenyl intermediate, Int(3+-8+)4 (+11.1 kcal/mol), retains the B(OH)2(OAc) side-product via Cu–O and OH···N interactions. Dissociation of this species with re-coordination of the free phen arm then forms [8]+ at +5.2 kcal/mol. Transmetalation therefore occurs with an accessible overall barrier of 21.9 kcal/mol but is endergonic by 5.2 kcal/mol. This is consistent with the nonobservation of any Cu-aryl species and low conversion to undesired products, when the reaction is performed in the absence of a halide source.34

Retention of the weakly bound κ1-N-phen ligand in TS(3+-8+) is important as in its absence, the overall barrier for an equivalent mono-phen pathway increases to 34.4 kcal/mol. Alternative transition states were also located in which MeOH or H2O solvent molecules act as H-bond acceptors to the boronate with similar overall computed barriers of 22.0 and 22.8 kcal/mol, respectively. Elongation of the Cu–N1 distance was far less marked in these cases (ca. 2.53 Å) and intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations indicated the direct formation of [8]+ with expulsion of AcOB(OH)2 (i.e., no intermediate equivalent to Int(3+-8+)4 was located). Other pathways, including those in which HO– was considered as a base, proved higher in energy; in addition, transmetalation with PhBpin gave a higher overall barrier of 26.9 kcal/mol (see SI Section S8.3).

Once [8]+ is formed, iodide can readily add to give Cu(phen)2(Ph)(I), 9, from which reductive elimination of PhI could in principle occur. However, this process would form a Cu(0) species and was shown to be thermodynamically inaccessible (ΔG = +18.1 kcal/mol). Instead, we propose that 9 undergoes disproportionation with a further equivalent of [3]+ to form Cu(I) species [Cu(phen)2]+, [10]+, and a Cu(III) species, Cu(phen)(I)(OAc)Ph, 11 (Figure 4b).

11 is the lowest of four low-spin square-pyramidal Cu(III) isomers that all lie with 4 kcal/mol; all of these structures are at least 17 kcal/mol less stable when computed as a high-spin triplet. Ph–I bond forming reductive elimination from 11 then proceeds with a minimal barrier of 1.1 kcal/mol to form an initial η2-PhI complex at +6.4 kcal/mol (see Figure 4c).35 Dissociation of the PhI product forms Cu(phen)(OAc), 12, at which AcO–/phen substitution forms [10]+ at −7.4 kcal/mol.

The DFT modeling studies indicate that bis-phen species are implicated both prior to ([3]+) and after ([8]+) the transmetalation step and that it is the disproportionation step that forms a mono-phen Cu(III) intermediate, 11. Both the transmetalation and the disproportionation steps are slightly endergonic, but the kinetically facile Ph–I reductive elimination from 11 drives the reaction to completion once coupled with the thermodynamically favorable formation of [Cu(phen)2]+, [10]+. The AcOB(OH)2 side-product formed in the computed mechanism would be readily hydrolyzed under the reaction conditions releasing AcOH. AcOH facilitates the Cu(I) oxidative turnover step with O2 to re-form [3]+ (see Figure 3)15−17 releasing AcO–, which is then available for the boronate formation that enables the transmetalation step under catalytic turnover.

Based on the totality of the dataset, an illustrative description of the proposed key events of the catalytic cycle is provided in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5. Proposed Catalytic Cycle with Computed Free Energy Changes and Activation Barriers (kcal/mol) Shown in Italics.

[Cu(OAc)2]2·2H2O undergoes denucleation in the presence of phen and NaI to give [3]+. [5]+ can, in principle, be accessed from [3]+, but the equilibrium is negligible. AcO– induces boronate formation from the arylboronic acid, facilitating transmetalation to give initially [8]+ that then adds I– to form 9. Disproportionation involving 9 and [3]+ gives 11 as the most stable Cu(III) species along with Cu(I) species [10]+ and so proceeds with loss of one phen ligand. 11 then undergoes reductive elimination, delivering the aryl iodide product and Cu(I) species 12. AcO–/phen exchange at 12 reforms [10]+ which undergoes oxidative turnover by action of AcOH and O2 to close the catalytic cycle. The Cu(I) dimer 6 can also be formed via anion metathesis at 12, although the formation of this species at 5.7 kcal/mol above [10]+ suggests that it is not directly implicated in catalysis.

In summary, a combination of experimental and computational investigations has provided the first complete description of the Cu-catalyzed iododeboronation reaction. This analysis has revealed the key role of the ligand in three critical steps—facilitating transmetalation via H-bonding to the boronate and promoting the key oxidative events (disproportionation and turnover). More specifically, ligand speciation is a key operation—ligand loss is favored at disproportionation, but gain is required at oxidative turnover, which provides a basis for understanding of ligand stoichiometry. From these data, future catalyst design principles can be constructed, with ligand stoichiometry crucial for catalytic turnover. This will be increasingly relevant in processes where turnover is a critical issue, such as the related fluorodeboronation reaction. This work therefore adds to the wider knowledge base of Cu-mediated oxidative coupling reactions and may support understanding, design, and development of related processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suzie Davison for help with control experiments. A.J.B.W. thanks the Leverhulme Trust for a Research Fellowship and the EPSRC Programme Grant “Boron: Beyond the Reagent” for support. The authors thank Dr Bela E. Bode for assistance with EPR measurements and Heriot–Watt University for a James Watt Scholarship to A.C. They also thank the Reviewers for insightful comments and helpful suggestions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Ac

acyl

- Ar

aryl

- IRC

intrinsic reaction coordinate

- phen

1,10-phenanthroline

- Ph

phenyl

- pin

pinacolato

Data Availability Statement

The research data supporting this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/8603890e-da81-4225-9343-a3f5baba470c. Crystallographic data for compounds [3]OAc, [3]Cl, 4, 5, and 6 are available from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under Deposition Numbers 2258899–2258903.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c02839.

Author Contributions

§ M.J.A. and A.C. contributed equally to this work. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Grant Nos. EP/R025754/1, EP/S027165/1, and EP/W007517/1. Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) Grant BB/R013780/1. Leverhulme Trust Grant No. RF-2022-014.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhang G.; Lv G.; Li L.; Chen F.; Cheng J. Copper-catalyzed halogenation of arylboronic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1993–1995. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.02.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Li Y.; Jiang M.; Wang J.; Fu H. General copper-catalyzed transformations of functional groups from arylboronic acids in water. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5652–5660. 10.1002/chem.201003711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge B. M.; Hartwig J. F. Sterically controlled iodination of arenes via iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 140–143. 10.1021/ol303164h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tale R. H.; Toradmal G. K.; Gopula V. B. A practical and general ipso iodination of arylboronic acids using N-iodomorpholinium iodide (NIMI) as a novel iodinating agent: mild and regioselective synthesis of aryliodides. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 84910–84919. 10.1039/C5RA18820B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heindel N. D.; Burns H. D.; Honda T.; Brady L. W.. The Chemistry of Radiopharmaceuticals; Mayson: New York, 1978; pp 1–294. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Zhuang R.; Guo Z.; Su X.; Chen X.; Zhang X. A highly efficient copper-mediated radioiodination approach using aryl boronic acids. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 16783–16786. 10.1002/chem.201604105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. C.; McSweeney G.; Preshlock S.; Verhoog S.; Tredwell M.; Cailly T.; Gouverneur V. Radiosynthesis of SPECT tracers via a copper mediated 123I iodination of (hetero)aryl boron reagents. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 13277–13280. 10.1039/C6CC07417K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S. W.; Makvandi M.; Kuiying Xu K.; Mach R. H. Rapid Cu-catalyzed [211At]astatination and [125I]iodination of boronic esters at room temperature. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1752–1755. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. C.Late Stage 18F-fluorination and 123I- iodination for PET and SPECT imaging. PhD Thesis; University of Oxford, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dong T.; Tsui G. C. Construction of carbon-fluorine bonds via copper-catalyzed/-mediated fluorination reactions. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 4015–4031. 10.1002/tcr.202100231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fier P. S.; Luo J.; Hartwig J. F. Copper-mediated fluorination of arylboronate esters. Identification of a copper(III) fluoride complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2552–2559. 10.1021/ja310909q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y.; Sanford M. S. Mild Copper-mediated fluorination of aryl stannanes and aryl trifluoroborates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4648–4651. 10.1021/ja400300g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredwell M.; Preshlock S. M.; Taylor N. J.; Gruber S.; Huiban M.; Passchier J.; Mercier J.; Génicot C.; Gouverneur V. A general copper-mediated nucleophilic 18F fluorination of arenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7751–7755. 10.1002/anie.201404436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West M. J.; Fyfe J. W. B.; Vantourout J. C.; Watson A. J. B. Mechanistic development and recent applications of the Chan–Lam amination. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 12491–12523. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. E.; Ryland B. L.; Brunold T. C.; Stahl S. S. Kinetic and spectroscopic studies of aerobic copper(II)-catalyzed methoxylation of arylboronic esters and insights into aryl transmetalation to copper(II). Organometallics 2012, 31, 7948–7957. 10.1021/om300586p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. E.; Brunold T. C.; Stahl S. S. Mechanistic study of copper-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling of arylboronic esters and methanol: Insights into an organometallic oxidase reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5044–5045. 10.1021/ja9006657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vantourout J. C.; Miras H. N.; Isidro-Llobet A.; Sproules S.; Watson A. J. B. Spectroscopic studies of the Chan–Lam amination: A mechanism-inspired solution to boronic ester reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4769–4779. 10.1021/jacs.6b12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y.; Kimura H.; Sasaki M.; Koike S.; Yagi Y.; Hattori Y.; Kawashima H.; Yasui H. Effect of water on direct radioiodination of small molecules/peptides using copper-mediated iododeboronation in water-alcohol solvent. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24418–24425. 10.1021/acsomega.3c01974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In this study ’disproportionation’ is taken to mean the reaction of two Cu(II) species that are not necessarily the same to give Cu(I) and Cu(III) intermediates.

- Vantourout J. C.; Li L.; Bendito-Moll E.; Chabbra S.; Arrington K.; Bode B. E.; Isidro-Llobet A.; Kowalski J. A.; Nilson M.; Wheelhouse K.; Woodward J. L.; Xie S.; Leitch D. C.; Watson A. J. B. Mechanistic insight enables practical, scalable, room temperature Chan-Lam N-arylation of N-aryl sulfonamides. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9560–9566. 10.1021/acscatal.8b0323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duparc V. H.; Schaper F. Sulfonato-diketimine copper(II) complexes: Synthesis and application as catalysts in Chan–Evans–Lam couplings. Organometallics 2017, 36, 3053–3060. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duparc V. H.; Bano G. L.; Schaper F. Chan–Evans–Lam couplings with copper iminoarylsulfonate complexes: Scope and mechanism. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7308–7325. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For stoichiometric Cu(III) complexes relevant to Chan–Lam chemistry, see:; a Ribas X.; Jackson D. A.; Donnadieu B.; Mahía J.; Parella T.; Xifra R.; Hedman B.; Hodgson K. O.; Llobet A.; Stack T. D. P. Aryl C–H activation by Cu(II) to form an organometallic aryl–Cu(III) species: A novel twist on copper disproportionation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2991–2994. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xifra R.; Ribas X.; Llobet A.; Poater A.; Duran M.; Sola M.; Stack T. D. P.; Benet-Buchholz J.; Donnadieu B.; Mahía J.; Parella T. Fine-tuning the electronic properties of highly stable organometallic CuIII complexes containing monoanionic macrocyclic ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2005, 11, 5146–5156. 10.1002/chem.200500088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S.; Dutta S.; Koley D. Entering chemical space with theoretical underpinning of the mechanistic pathways in the Chan–Lam amination. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 1461–1474. 10.1021/acscatal.1c04479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jing B.; Li L.; Dong J.; Xu T. (Acetato-κO)bis(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N’)copper(II) acetate heptahydrate. Acta Cryst. 2011, E67, m464 10.1107/S1600536811009676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux M.; O’Shea D.; O’Connor M.; Grehan H.; Connor G.; McCann M.; Rosair G.; Lyng F.; Kellett A.; Walsh M.; Egan D.; Thati B. Synthesis, catalase, superoxide dismutase and antitumour activities of copper(II) carboxylate complexes incorporating benzimidazole, 1,10-phenanthroline and bipyridine ligands: X-ray crystal structures of [Cu(BZA)2(bipy)(H2O)], [Cu(SalH)2(BZDH)2] and [Cu(CH3COO)2(5,6-DMBZDH)2] (SalH2 = salicylic acid; BZAH = benzoic acid; BZDH = benzimidazole and 5,6-DMBZDH = 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole). Polyhedron 2007, 26, 4073–4084. 10.1016/j.poly.2007.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle P.; Hathaway B. J. Structure of iodobis(1,10-phenanthroline)copper(II) iodide monohydrate. Acta Cryst. 1991, 47, 1386–1389. 10.1107/S0108270190014081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.-H.; Lü Z.-L.; Xu J.-Q.; Bie H.-Y.; Lu J.; Zhang X. Synthesis, characterization and optical properties of some copper(I) halides with 1,10-phenanthroline ligand. New J. Chem. 2004, 28, 940–945. 10.1039/B314974A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seco J. M.; Quirós M.; Garmendia M. J. G. Synthesis, X-ray crystal structure and spectroscopic, magnetic and EPR studies of Cu(II) dimers with methoxy-di-2-pyridyl)methoxide as bridging ligand. Polyhedron 2000, 19, 1005–1013. 10.1016/S0277-5387(00)00356-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latham K.; Mensforth E. J.; Rixa C. J.; White J. M. Synthesis of supramolecular metallo-amine-oxy acid systems via crystal disassembly/reassembly. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 1343–1351. 10.1039/b822193f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DFT calculations employed Gaussian16 with geometries optimized with the BP86 functional including methanol solvent through the PCM approach. An SDD pseudopotential and basis set was employed for Cu and 6-31g** for all other atoms. Electronic energies were corrected for dispersion (BJD3) and basis set effects (def2tzvp) and combined with the thermochemical corrections from the initial optimizations to give the free energies in the text. See SI for full details and references.

- Addison W.; Rao T. N.; Reedijk J.; van Rijn J.; Verschoor G. C. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; The crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984, 1984, 1349–1356. 10.1039/DT9840001349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy J. J.; O’Rourke K. M.; Frias C. P.; Sloan N.; West M. J.; Pimlott S. L.; Sutherland A.; Watson A. J. B. Mechanism of Cu-catalyzed aryl boronic acid halodeboronation using electrophilic halogen: Development of a base-catalyzed iododeboronation for radiolabeling applications. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2488–2492. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In contrast, Koley and co-workers in their study of the Chan–Lam reaction found the rate-limiting transition state corresponded to reductive elimination (see ref (24)). In that study the B3LYP functional was employed. Accordingly, to assess any functional dependency, we recomputed our results with B3LYP and found that transmetalation remains rate-limiting.

- Disproportionation to give [Cu(phen)2(Ph)I)]+ and [Cu(phen)2]+ is 1.7 kcal/mol less accessible than the process in Figure 4b; Ph-I reductive elimination from [Cu(phen)2(Ph)I)]+ involves a transition state at +12.4 kcal/mol.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The research data supporting this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/8603890e-da81-4225-9343-a3f5baba470c. Crystallographic data for compounds [3]OAc, [3]Cl, 4, 5, and 6 are available from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under Deposition Numbers 2258899–2258903.