Summary

Globally, the need to enhance the diversity of trial participants is receiving increasingly urgent attention. We wanted to know whether trials run in India had adequately sampled the country's enormous ethnic diversity. We accessed the Clinical Trials Registry-India website to determine whether each interventional drug or biologic Phase 2 or 3 study, registered in a recent five-year period had run in each of six geographic zones. As regards Phase 3 trials conducted only in India, 61.4% ran in a single zone and just 6.8% were conducted in all six zones. Multinational Phase 3 trials had a better distribution since 3.6% had run in just one zone and 7.1% in all six. India's diverse ethnic groups are underrepresented in the majority of trials covered in this study. A trial that is conducted on non-representative groups and later discovered to be harmful or ineffective in parts of the population, is unethical. We propose various remedial steps.

Keywords: Ethnicity, Clinical trials, Trial registries, CTRI, Equity

Introduction

Several categories of individuals tend to be underrepresented in clinical trials. These include children, sexual minorities, etc. This has real consequences for medical care.1 In the United States (US), guidelines, legislation and enrollment tactics have attempted to remedy the situation1,2 and trials have become more inclusive over the past 25 years.3

Here we focus on ethnic diversity. The International Conference on Harmonization issued the ICH E5 guidelines in 1998, that described intrinsic (such as genetic or physiologic) and extrinsic causes (such as cultural practices) for ethnic differences between populations.4 In order to ensure that drugs developed in the West could be sold in Asia, for instance, without repeating a large trial in the new region, bridging studies were designed that would test for safety, efficacy, suitable dose etc. in the new region. The need to include various ethnic groups in clinical research has been emphasized in India as well. Both the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare in 2012,5 and the Ranjit Roy Chaudhury Committee in 20136 mentioned the need to include different ethnicities in trials. In this study, we accessed the Clinical Trials Registry - India (CTRI) and investigated whether interventional drug and biological Phase 2 and Phase 3 studies had run in the six zones of the country, ie., Eastern, Western, Northern, Southern, Central, and North-Eastern. We also examined which zones, and which cities in each zone, had hosted the maximum number of trials.

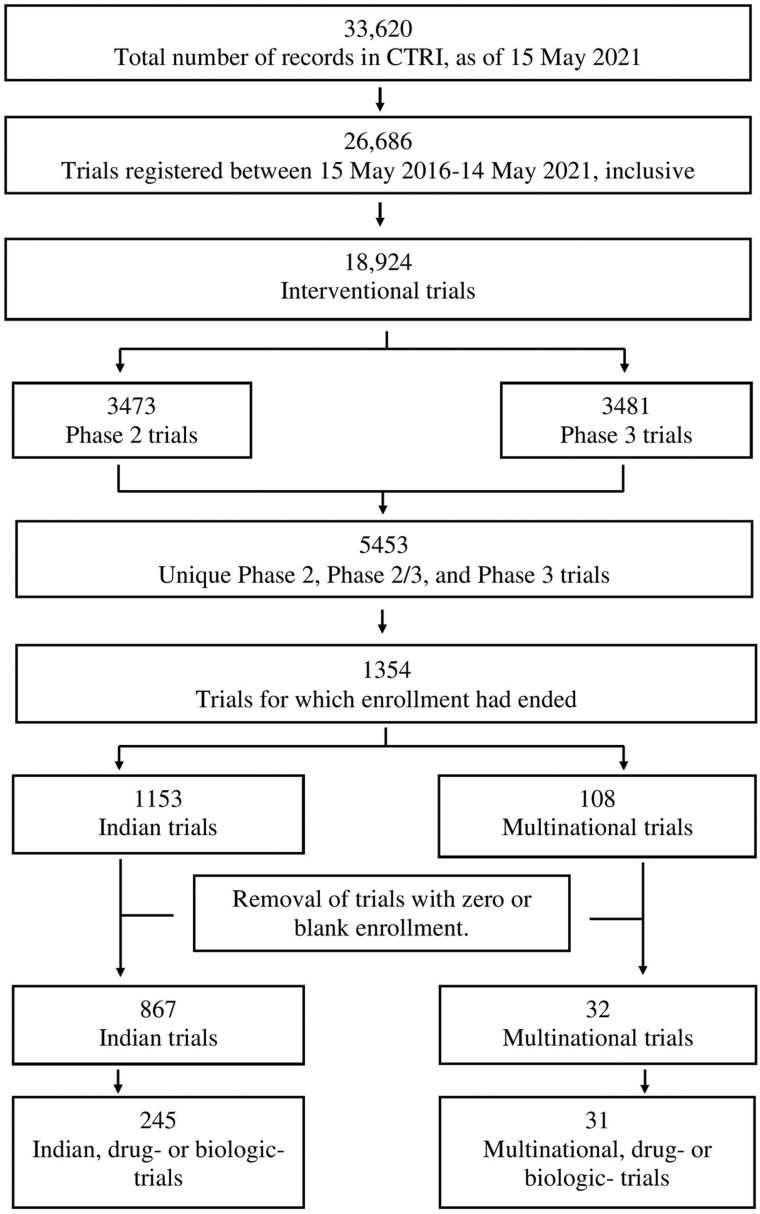

We accessed the CTRI website (http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/advancesearchmain.php) on 15 May 2021. We went on to process the data as shown in Fig. 1. Further details of the methodology are available in Appendix 1 File (https://osf.io/jxpkm), which refers to Appendix 2–5 Files, and Appendix 1–8 Tables.

Fig. 1.

Process of identifying the interventional drug and biological Phase 2 or Phase 3 trials that ran in India in a recent 5-year period.

Our dataset comprised interventional drug or biological Phase 2 or Phase 3 trials for which enrollment was complete, and that had run in India in a recent five-year period. Phase 3 trials included Phase 2/3 trials. Some results are presented briefly below. Data related to the Indian trials (ITs) and the Multinational trials (MTs) are presented in greater detail in Appendix 5 Table (https://osf.io/eyv3a) and Appendix 6 Table (https://osf.io/bwxaf) respectively.

The 163 Phase 3 ITs had 1049 sites, and the 28 Phase 3 MTs had 349 sites. The number (and percentage) of trials with sites in different numbers of zones is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

For the Indian and multinational trials in Phase 3, the number of zones in which each trial had run.

| Number of zones | 163 Indian trials |

28 multinational trials |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of trials | Percentage | Number of trials | Percentage | |

| 1 | 100 | 61.4 | 1 | 3.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 1.8 | 3 | 10.7 |

| 3 | 9 | 5.5 | 8 | 28.6 |

| 4 | 13 | 8.0 | 7 | 25.0 |

| 5 | 27 | 16.6 | 7 | 25.0 |

| 6 | 11 | 6.8 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Total | 163 | 100 | 28 | 100 |

For both the ITs and MTs, the Western and Southern zones have the most sites, and the Eastern, Central and North-Eastern, the least, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

For the Indian and multinational trials in Phase 3, the number and percentage of sites in each zone.

| Trials in each zone | 163 Indian trials |

28 multinational trials |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of sites | Percentage | Number of sites | Percentage | |

| Western | 362 | 34.5 | 110 | 31.5 |

| Southern | 254 | 24.2 | 132 | 37.8 |

| Northern | 195 | 18.6 | 52 | 14.9 |

| Central | 113 | 10.8 | 22 | 6.3 |

| Eastern | 107 | 10.2 | 31 | 8.9 |

| North-Eastern | 18 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Total | 1049 | 100 | 349 | 100 |

For both sets of trials, 1–4 cities accounted for 50% or more of the trials in a given zone, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

For the Indian and multinational trials in Phase 3, the top cities that accounted for 50% or more of the trials in a given zone.

| Zone | Top cities for 163 Indian trials | Top cities for 28 multinational trials |

|---|---|---|

| Central | Lucknow (48.7%), Kanpur Nagar (20.4%) | Lucknow (31.8%), Indore (22.7%) |

| Eastern | Kolkata (57.9%) | Kolkata (64.5%) |

| North-Eastern | Kamrup (83.3%) | Kamrup (50%), Jorhat (50%) |

| Northern | Delhi (37.9%), Jaipur (31.3%) | Delhi (48.1%), Jaipur (19.2%) |

| Southern | Hyderabad (21.3%), Bangalore (21.3%), Srikakulam (8.3%) | Hyderabad (19.7%), Bangalore (15.9%), Chennai (10.6%), Coimbatore (6.8%) |

| Western | Ahmedabad (19.9%), Pune (16.6%), Mumbai (15.5%) | Pune (25.5%), Ahmedabad (19.1%), Mumbai (18.2%) |

Also, we have analyzed Census 2011 data and found that the Scheduled Tribe population was 10% or more of the total population in 238 (37.2%) of the 640 districts in India. The distribution of such districts per zone is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Per zone, the number of districts with a Scheduled Tribe population that is 10% or more of the total population, and the fraction per zone.

| Zone | Number of districts | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| North-Eastern | 69 | 29.0 |

| Central | 53 | 22.3 |

| Eastern | 44 | 18.5 |

| Northern | 28 | 11.8 |

| Western | 25 | 10.5 |

| Southern | 17 | 7.1 |

| Islands | 2 | 0.8 |

| Total | 238 | 100 |

We see that the fraction of tribal population was higher in zones with the fewest trials, ie North-Eastern, Central and Eastern.

Finally, we characterized each (a) Phase 2 and Phase 3 and (b) Phase 3 trial from the viewpoint of type of study, intervention, year of registration, the health condition investigated, the sponsor, and the PI. Details are available in Appendix 7 Table (https://osf.io/p7vkw) and Appendix 8 Table (https://osf.io/2ghnm) for the ITs and MTs respectively, and are discussed in Appendix 6 File (https://osf.io/r7mhp).

Discussion

Why should studies sample a range of ethnicities? Around 20% of the drugs approved in recent years in the US have had differential outcomes based on ethnicity.7 The difference in outcomes between different groups may be in the efficacy of the drug, or in the incidence of side effects, or their nature and severity.8 Some of these differential outcomes are due to genetic factors, and others to lifestyle.9 For these reasons, and due to the growing number of Asians living in Western nations, the regulators in those countries also seek wider ethnic representation in trials, and welcome data from the Asia–Pacific region, for example.10

The Government of India's Indian Council of Medical Research has indicated that adequate sampling of ethnicities requires enrollment from six zones of the country.11 Therefore, we set out to examine whether each Phase 2 or Phase 3 interventional drug or biologic study had run in each of these six zones. Although each zone had a mix of ethnicities, the dominant ethnicity per zone varied.12 In this study, we assumed that each zone had a different ethnicity from the others. As such, this was a top-level assessment of whether each study had sampled a broad enough set of ethnicities.

For the Phase 3 ITs, it is astounding that 61.4% ran in a single zone, and a minuscule 6.8% ran in all six zones. Although the MTs did better, both were a far cry from the ideal situation, where each study would have run in all six zones. For both the ITs and the MTs, the Southern and Western zones have the most sites, and the Eastern, Central and North-Eastern, the least. Whereas some of these data are understandable – the North-Eastern region has fewer medical facilities than big metropolises such as Bangalore and Mumbai,13 and is also known to have poor connectivity14 – some of them are not as clear.

Going beyond the number of zones sampled, we would have liked to determine the fraction of participation from each zone in a given study. However, CTRI provided the enrollment per study and not per site, and so we were unable to pursue that angle.

Within each zone, the trials cluster in certain cities, but it is again not always clear why these particular cities were popular. Some cities are easily understood: Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Bangalore are large cities with a large number of hospitals. However, for example, Indore (Central zone), Jaipur (Northern zone) and Kamrup (North-Eastern zone) could probably have been substituted by Bhopal, Chandigarh and Guwahati respectively. It is known14 that there are particular criteria that sponsors use to identify suitable sites in India. However, it is not known why particular cities were not popular amongst sponsors.

It is concerning that most interventional drug or biologic trials did not adequately sample the very wide range of ethnicities in India, even at a top-level consideration of these ethnicities. In large trials in particular, it is important to have wider ethnic representation so that the possibility of different treatment effects in different ethnic groups can be explored. Providing patients with ineffective drugs, exposing them to unnecessary toxicity, denying particular groups of patients the opportunity to benefit from a trial and post-trial access, and wasting the efforts of volunteers are all ethical transgressions. We realize that increasing the ethnic diversity of trials may increase trial costs. Whether such increased costs would lead to fewer treatments being developed is a question that would need separate investigation. Further, we should also bear in mind there are costs to developing drugs that have safety or efficacy concerns in parts of the population.

Although both the 59th Parliamentary Standing Committee Report and the Ranjit Roy Chaudhury Committee report emphasized the need to sample a wide variety of ethnicities, this is not mandated by the Government of India's New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules, 2019.15 Also, unlike many other registries, and in contradiction to WHO recommendations, CTRI does not have a field for the reporting of trial results.16 Since 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has required that the race and ethnicity of each participant, if captured, needs to be submitted. This led to a big upsurge in the reporting of such data in registry records.17 As such, if the government required it, this data could also be captured by CTRI. However, to its credit, and consistent with WHO requirements, CTRI does have a field asking for a data sharing plan for Individual Participant Data (IPD). Although stating a willingness to share IPD does not always translate to sharing this data,18 if sponsors do share IPD, some ethnicity data may become available.

In earlier work we have made various recommendations that would make CTRI world class.16 For instance, the managers of CTRI could easily include a ‘Results’ field in a trial record. These results could require disaggregated data based on ethnicity and other demographic indicators. The Indian government could also make explicit its expectations in terms of wider ethnic representation—and reporting—in Phase 3 trials in particular. In the medium term, the Indian regulator should—like the USFDA—make public the regulatory documents pertinent to a drug's approval.16 These would contain summary demographic details of those who participated in the trial(s). Furthermore, such documents need to be searchable and user-friendly. In the medium to long term, under-served regions of the country need to have more medical facilities. Whereas the primary reason for such facilities would be regular medical care, they could also be used to improve the diversity of ethnic representation in trials.

Finally, this study had certain limitations. First, we only examined whether each trial had run in six zones of the country. Ideally, one would have liked to determine whether it had sampled ethnicities at much greater granularity. However, such information is unavailable in the public domain and may not exist at all. Second, due to the many categories of Type of Study, we probably missed some of the relevant drug or biologic studies. We do not know whether our results are mirrored by the trials that were left out. And third, we examined records that were registered only in a recent five-year period, and do not know whether earlier records would have similar results.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined trials registered with CTRI in a recent 5-year period to investigate whether each Phase 2 or Phase 3 interventional drug or biologic trial had run in the six zones of the country, thereby sampling the diverse ethnicities of India. Most had not. We have suggested various steps that could be taken to improve the situation. Also, similar analyses probably need to be carried out in other countries in which particular regions are dominated by specific ethnicities, if wide ethnic representation in each trial has not been ensured by other means.

Contributors

GS – conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. JM – Data curation, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, writing - review & editing. IC – data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing - review & editing. MP – investigation, software, writing - review & editing. MK - formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing - review & editing. SV – formal analysis, writing - review & editing. RV – formal analysis, methodology, validation, writing - review & editing. All authors (a) contributed to, and approved, the final version of the manuscript, (b) had access to all the data in the study and (c) had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by internal funding of the Institute of Bioinformatics and Applied Biotechnology, from the Department of Electronics, Information Technology, Biotechnology and S&T of the Government of Karnataka, India. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100230.

Contributor Information

Jaishree Mendiratta, Email: mendiratta.jaishree@yahoo.com.

Mounika Pillamarapu, Email: mounikarp95@gmail.com.

Indraneel Chakraborty, Email: indraneel0207@gmail.com.

Ravi Vaswani, Email: ravi.vaswani@yenepoya.edu.in.

Mudit Kapoor, Email: mudit.kapoor@gmail.com.

Sreekar Vadlamani, Email: sreekar@tifrbng.res.in.

Gayatri Saberwal, Email: gayatri@ibab.ac.in, gayatri.saberwal@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Aronson L. A new NIH rule won't be enough to make clinical research more inclusive. [Internet] STAT. 2019. https://www.statnews.com/2019/01/31/nih-rule-make-clinical-research-inclusive/ [cited 2023 May 4] Available from:

- 2.Kennedy E.M. S.1 - 103rd Congress (1993-1994): National institutes of health revitalization act of 1993. [Internet] 1993. https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/senate-bill/1 [cited 2023 May 4] Available from:

- 3.May M. Twenty-five ways clinical trials have changed in the last 25 years. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):2–5. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow S.C., Shao J., Hu O.Y.P. Assessing sensitivity and similarity in bridging studies. J Biopharm Stat. 2002;12(3):385–400. doi: 10.1081/bip-120014567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of India, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare . Rajya Sabha Secretariat; New Delhi: 2012. Fifty-ninth report on the functioning of the central drugs standard control organisation (CDSCO)http://164.100.47.5/newcommittee/reports/englishcommittees/committee%20on%20health%20and%20family%20welfare/59.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Government of India . 2013. Report of the Prof. Ranjit Roy Chaudhury Expert Committee to formulate policy and guidelines for approval of new drugs clinical trials and banning of drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bumpus N.N. For better drugs, diversify clinical trials. Science. 2021;371(6529):570–571. doi: 10.1126/science.abe2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knepper T.C., McLeod H.L. When will clinical trials finally reflect diversity? Nature. 2018;557(7704):157–159. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abroad Indians. NDTV.com; 2020. Indian-origin doctors warn of racial bias in medical research in UK [Internet]https://www.ndtv.com/indians-abroad/indian-origin-doctors-warn-of-racial-bias-in-medical-research-in-uk-2265389 [cited 2023 May 4]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost & Sullivan . 2020. Asia: preferred destination for clinical trials. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A. To conduct large scale clinical trials, ICMR calls for entries in Indian Clinical Trial & Education Network. [Internet] 2021. https://www.timesnownews.com/mirror-now/in-focus/article/to-conduct-large-scale-clinical-trials-icmr-calls-for-entries-in-indian-clinical-trial-education-network/816533 [cited 2023 May 4]. Available from:

- 12.Majumder P.P., Basu A. A genomic view of the peopling and population structure of India. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2015;7(a008540) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapoor G., Hauck S., Sriram A., et al. State-wise estimates of current hospital beds, intensive care unit (ICU) beds and ventilators in India: are we prepared for a surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations? [Internet] medRxiv. 2020 https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.16.20132787v1 2020.06.16.20132787[cited 2023 May 4] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bangera S., Latha M.S. Site selection for clinical research in India. Asian J Pharmaceut Clin Res. 2015;10–4 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Govt of India. Notification The Gazette of India: Extraordinary, Part II, Section 3, Subsection (i), New Delhi. 2019. https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/export/sites/CDSCO_WEB/Pdf-documents/NewDrugs_CTRules_2019.pdf pgs 1–264. [Internet]. Ministry of Health GSR Notification #227; 2019. Available from:

- 16.Saberwal G. How to make clinical trials registry-India world class. Curr Sci. 2023;124(7):785–789. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fain K.M., Nelson J.T., Tse T., Williams R.J. Race and ethnicity reporting for clinical trials in ClinicalTrials.gov and publications. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;101 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esmail L.C., Kapp P., Assi R., et al. Sharing of individual patient-level data by trialists of randomized clinical trials of pharmacological treatments for COVID-19. JAMA. 2023 doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.