ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Violence against physicians is a global issue that causes impaired physical and mental health, declined work quality, resignations, and even suicides. Studies regarding violence against physicians are very limited. Therefore, our aim is to investigate the physical violence incidents against physicians presented in print media between 2008 and 2018.

METHODS:

A total of 8612 news reports acquired in national news database via 45 keywords were assessed. Five hundred and sixty-four of the reports met the inclusion criteria and were retrospectively analyzed.

RESULTS:

Of 5964 news reports, 3754 (62.9%) were reprimands and protests against violence incidents. In 11 years, 560 individual incidents occurred where 647 physicians were physically assaulted, with 2267 news reports written on those incidents. The number of incidents increased over the years, and in 2012 both the number of incidents (n=91) and news reports count per incident were found highest. About 77.7% of assaulted physicians were male, and incident rate was higher in Western Turkey (42.15%). In 11 years, ten dedicated physicians have lost their lives in the line of duty. Emergency medicine (20.4%), primary care (9.89%) were the departments most exposed to physical violence. The claim of receiving inadequate medical attention was noted to be the primary allegation of the assailants.

CONCLUSION:

The frequency of physical violence incidents against physicians is increasing. Throughout the study period, news reports containing condemnations, critiques, and protests are also more frequently, yet not adequately, placed in print media. Thus, social and public awareness ought to be enhanced through national and global media outlets. Furthermore, extensive measures must be taken by governments in order to prevent and eliminate violence.

Keywords: Doctors, healthcare workers, physical assault, physicians, violence, workplace violence

INTRODUCTION

Physicians, along with other healthcare workers (HCW) are victims of workplace violence (WPV) with an increasing incidence while trying to serve their community.[1–3] To this day, many studies have been conducted to reveal just how big of current problem violence in healthcare is, in both developed and developing countries.[4,5] Physical violence against physicians in hospital settings is an ever-increasing issue in Turkey.[6,7] According to a research with a sample size of 1209; 49.5% of HCW reported that they have experienced at least one form of violence in the previous year; verbal violence rate was 72.4%, whereas physical violence rate was found 11.4%.[8] Another study involving 713 physicians in the emergency department (ED), reports of a 31.1% physical violence rate.[9]

The World Health Organization defines violence as: “The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either result in or have a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.” Various outcomes have been associated with violence against physicians; physical injury rates were found between 49 and 65%, whereas 15–60.4% of the victims received medical treatment.[10] Burnout, depersonalization, decreased sleep quality and subjective health, increases in resignations, and negative economic impacts were some of the other outcomes listed in various studies.[1,10,11]

In many cases, violence against physicians is underreported due to feelings of incompetence, shame, and fear of being impugned.[1] The misbelief that violence is an occupational hazard is one of the most dangerous reasons for underreporting; hence, it is crucial to consider the provoking effects of the media on this matter. A significant number of physicians are subjected to WPV, which is suggested in numerous studies, yet the reflection of these numbers onto public through media channels is unclear although the impact of the media in the process is mentioned by few authors.[7,8,12,13] Li et al.[12] report that while 68.6% of the study sample in Chinese Children’s Hospital staff was exposed to at least one WPV incident during the previous year, only seven cases of serious injuries have been reported in the media in 18 months. Wu et al.[14] analyzed 124 online newspaper reports which were mentioned to be “tip of the iceberg.” Data that would clarify the frequency and extension of the printed media concerning physical violence against physicians, is however lacking.

To the best of our knowledge, while previous studies have investigated the incidence of violence against physicians in Turkey, a systematical research regarding the reflection of such incidents in the media is lacking. This study aims to investigate the total number of physical violence against physicians in the printed media. We also aim to evaluate how many times each incident was mentioned throughout the study period, and how much attention they have attracted among the community and government through protests and/or condemnations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study investigating how often news regarding physical violence against physicians takes place in local and national printed media in Turkey. Data regarding violence against physicians was obtained through a nationwide print media archive, a database containing each and every news reported in print, audio, and visual media outlets; printed media being newspapers and journals. The news between January 2008 and December 2018 was scanned using 45 keywords including synonyms and combinations of research topics such as “violence against physician, physicians and hitting, physicians and beating, violence to physicians, injuries of physicians, and violence in medicine.”

A total of 8612 news were obtained which included a broad range of news in relevant topics. News reports were evaluated according to inclusion and exclusion criteria by three independent researchers. Within these, news about violence against HCWs that did not include physicians, news about incidents that took place earlier than determined dates, verbal or psychological violence incidents with no mention of physical violence was excluded from the study. While news directly about physical violence against physicians; news about the follow-up trial on an incident that took place within 2008–2018; news condemning violence against physicians through a commentary; news about protests and condemnations of violence against physicians were included in the study.

After checking for suitability, a total of 5964 news reports were included in the study. Each report was meticulously reviewed and sorted according to whether the reports are of actual violence acts, or articles including condemnations and protests. The violence acts were then reviewed according to the date of the incident, gender, department, and title of the physician, gender of the assailant, number of assailants, the hospital and city the incident took place, and reasons for the violence. Any data lacking in reports were marked as not given while and in case of questionable information a group concensus was reached.

RESULTS

A total of 8612 news reports related to physical violence against physicians were found via national media archive. Five hundred and sixty-four of these reports met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated. Two hundred and sixty-seven (38%) of them were directly about physical violence against physicians, and 3754 (62.9%) news included condemnation. A total of 560 individual incidents was reported in printed media between 2008 and 2018, where 647 physicians were physically assaulted. At this period of time, 10 physicians (1.54%) have lost their lives to vicious assaults, and three of the assaults occurred in 2015. Violence incidents mostly took place in 2012 (16.25%) and 2013 (15.53%). The years that printed media most frequently featured reports regarding violence were 2015 (18.8%), 2013 (18%), and 2012 (16%), respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A general outlook at distribution of physical violence against physicians’ news between 2008 and 2018.

When specialities of the physicians were analyzed, emergency medicine physicians (30.84%) were found to have suffered from violence the most who were followed by primary care physicians (14.95%) and pediatricians (7%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of violence cases by specialties of physicians

| Speciality | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency | 132 | 20.4 |

| Primary care | 64 | 9.89 |

| Pediatrics | 30 | 4.64 |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 29 | 4.48 |

| Orthopaedics | 18 | 2.78 |

| Ambulance | 17 | 2.63 |

| Psychiatry | 17 | 2.63 |

| Others | 122 | 18.86 |

| Total | 647 | 100 |

Majority of the assault victims were male (77.7%). Although the majority of the perpetrators’ gender was not defined in the news reports, remaining reports that gender was revealed, 90% of the assailants were reported male (n=195). In addition, the number of incidents with single perpetrators (n=374) was twice as much as of those with multiple assailants (n=186).

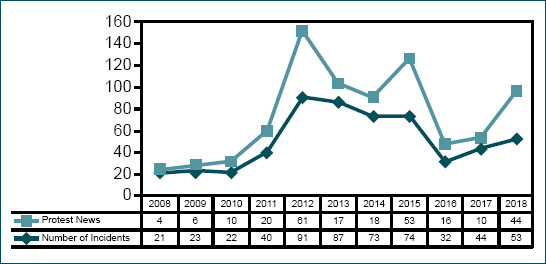

Physical violence against physicians has been reported in 67 of 81 provinces of Turkey. Istanbul had the highest number of incidents with 59 cases. 42.15% of the assaults occurred in Western regions of Turkey which include Marmara (28.04%) and Aegean Regions (14.11%), while 15.56% occurred in Southeastern regions. Investigation of the allegations of the assailants indicates that the claim of receiving inadequate medical attention (18.21%) was noted to be the primary reason for resorting to violence, followed by being rejected of demands for illegal procedures (14.46%) (Table 2). The claim of receiving inadequate medical attention had been explained by patients as supposedly waiting a long time for examination or late interventions. Demands for illegal procedures include mostly wrongful medical reports and prescriptions or drugs requests (59.25%). In 28.92% of cases, the underlying reason for the violence could not be acquired from the news reports. The correlance between the number of incidents and the frequency of protests against violence incident that took part in the media varies by years. Between 2008 and 2018, 259 news regarding those protests were published, most of which were published in years 2012 (23.55%), 2015 (20.46%), and 2018 (16.98%), respectively (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Reasons for physical violence against physicians

| Reason for violence | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| The claim of receiving inadequate | 102 | 18.21 |

| medical attention | ||

| Being rejected of demands for illegal | 81 | 14.46 |

| procedures | ||

| Argument between physician and | 77 | 13.75 |

| patient and/or relatives | ||

| Holding physician responsible for | 49 | 8.75 |

| patient’s death | ||

| Dissatisfaction about treatment | 47 | 8.39 |

| Being under the influence of alcohol | 25 | 4.46 |

| Having a psychiatric illness | 8 | 1.43 |

| Unknown | 162 | 28.93 |

| Total | 560 | 100 |

Figure 2.

Correlation between number of protest news and number of incidents by years.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that 2267 written news about 560 individual cases of physical violence against physicians have been reported in 11 years. They were sorted according to sociodemographic properties of the assailants and physicians, region, department, date, and the reasons for the violent acts.

Even though violence against physicians has global significance, there is yet no consensus on evaluation, and classification of WPV in healthcare settings.[4] In India, 40.8% of resident physicians were reported to have experienced violence, while the incidence rate was found to be 83.4% in China, and 50.6% in Norway.[5,15]

Numerous studies have been conducted in Turkey in order to objectively enlighten this matter of violence. Pinar et al.[16] reported one of the most extensive studies of Turkey revealing that 44.7% of 12.944 HCWs who participated in the survey have been subjected to violence incidents while on duty within last year; among which 43.2% of these were of verbal violence incidents, where 6.8% were physical assaults.

Although female physicians were found to have a higher risk of exposure to aggressive behavior in previous studies and reviews, physical assaults are more likely to be subjected upon males, which also is in compliance with our study revealed that the majority of the physicians physically assaulted were male. [15,17,18] Incidents involving a single perpetrator were found to be more common, and the majority of the assaults are conducted by male perpetrators, according to reviews.[8,12,13]

ED physicians constitute approximately one-third of all violence victims of the incidents reported, with twice as much frequency compared to primary care physicians. This finding is in accordance with several other studies.[4,8,15] Li et al.[12] reported that while the oncology department has the highest rates of overall violence, cases of physical violence are more frequent in EDs. Anand et al.[15] draw attention that physicians who are involved with a patient’s loss, are more likely to get assaulted by the relatives of the deceased patients, who tend to be more stressed, anxious, and aggressive. According to a study among ED physicians from across Turkey, 78.6% of them reported to have experienced WPV; 65.9% of which were recurring incidents, and physical violence was a third common form of violence with an incidence of 31.1%.[9] Another study reveals that WPV is the most frequent cause of resignation among ED residents in Turkey.[19] In the USA, a survey has been conducted with 263 participants, reporting that 78% of them having experienced at least one kind of violence in the previous year, with 21% of the incidents being physical assaults, wherein another study from Iran, physical violence against resident physicians in ED was reported as 68.6% of the study population.[17,20]

Evaluation of the causes and alleged reasons of the assaults revealed that the assailants mainly claimed that care and attention of the physician was inadequate, which was most frequently a conclusion based on long waiting periods. The assailants’ second most common motives were being denied of demands for illegal procedures such as; forging a medical report, unnecessary and/or illegal drug prescriptions. Kumar et al.[3] also report long waiting periods as the most common cause of violence incidents, while Bayram et al.[9] reports that in the ED, overcrowded emergency rooms were blamed in violence. Insufficient knowledge and awareness of the community regarding the duties of the resident physicians were reported as predisposing factors for violence.[20] Hacer and Ali[21] reported that low socio-cultural status and inadequate education are important underlying reasons. Emam et al.[20] report that effective use of police forces combined with increased security measures substantially prevent WPV against physicians. Issues such as inadequate healthcare policies, long waiting periods, and overcrowded emergency rooms all could only be resolved and ameliorated by firstly investigating and understanding the underlying causes, defects, and faults of the healthcare system, and then developing and executing new and improved policies. People should be well informed that it is beyond physicians’ powers to change and improve the healthcare policies without a full support and proper regulations provided by governments.

Our data indicate that violence incidents against physicians most frequently occurred in Western Turkey, which correlates with the distribution of population, confirming that the relation between overpopulation and controversially insufficient healthcare settings are thought to be important factors related with violence. Considering seven regions of Turkey, Southeastern Anatolia region had the second-highest rates of violence cases following the Marmara Region, which contains the highest number of population. Southeastern Anatolia, on the other hand, has the lowest overall average of educational levels, which unfortunately indicates the magnitude of illiteracy and ignorance having such crucial impacts on the well-being of both public and HCW.[22] Hence, it is vital to develop new methods in order to enhance the education of the people. Lack of communicational skills of both victims and perpetrators also has a huge impact on escalating violence, which means that HCW ought to be educated and prepared against severely stressful situations. However, it should be remembered that violence against physicians is still an issue in developed countries with higher socio-economical conditions.

The consequences of violence against physicians are serious, bearing psychological, occupational, and physical outcomes. [11,19] As indicated in previous studies, many of the victims might have feelings such as depression, anxiety, and humiliation.[23] Yet, underreporting is a significant issue which is caused by the belief that nothing would change.[9] This belief also triggers feelings of worthlessness, anger, self-distrust, burn- out, while affecting HCWs decision-making; leading to, absences from the workplace, reduced work performance, acute traumatic syndrome, traumatic injuries, and even suicidal attempts.[2,19–21]

Underreporting violence incidents in healthcare settings still remains as a global unresolved matter.[4,16] According to Furin et al.[24] only 76 (48.7%) out of 156 emergency medical personnel have reported violence while even fewer of them seeked medical care. In another study, only 30.9% of victims have reported the attacks to their supervisors and the most common causes of underreporting were; the thought of that reporting would not have an efficient or adequate outcome and that the violence itself is a common occupational hazard, thus reporting would be useless.[2,25] There is no definitive study about people’s general perception and awareness of violence against physicians, but it is highly possible to witness a considerable amount of people accepting violence as usual or even necessary. According to an online poling in China, only 6.8% of 6.161 respondents did not approve violence against physicians while a majority was satisfied with it.[13]

Our study also puts emphasis on media’s stand towards physical violence against physicians. A total of 3754 news reports were condemning the violence against physicians, and 241 protest actions were covered in media in 11 years. Protest actions reached a peak in 2012 with 61 gatherings, which was followed by 2015 (n=53) and 2018 (n=44). 2012 holds the highest number of assaults, with also the highest number of protest events. 2015 was the year that three physicians were murdered in vicious attacks, thus it was the year that the highest media coverage per incident was achieved. It is possible to consider these as proof that the level of perception on WPV against physicians is mostly proportional to how much attention was paid to these incidents in the media. However, in 2017 that two physicians were murdered, only 10 protests took place. Even though news reports per incident were higher than those in 2012; protest numbers remained low. This might be associated with the current political and economical status of the country during those years, although there is no certainty of it.

Violence against physicians is supposed to be preventable, yet in eleven years, ten physicians were failed to be saved and lost their lives against violence. This number may be low compared to mortality rates in China (6.8%), but it still represents ten individual lives taken while serving the people of our community.[13]

There were a total of 144.327 registered physicians in Turkey, according to 2016 data; 40.544 of them being specialists, 37.173 being primary healthcare physicians, and 8.615 being residents.[26] According to the previous studies from Turkey, about 10% of HCWs experience physical violence in one year; which represents approximately 14.000 physicians who were assumed to be victims of physical violence; some having experienced more than one assault.[8,9,16,27] Our study has the maximum number of printed media news per year of 427 which was in 2015, reporting 74 individual incidents. This number is nowhere near the estimated physical violence cases against physicians. Considering that verbal and psychological assaults are more commonly seen, this gap between the true situation in hospitals and public knowledge is probably wider.

Our study has some limitations that deserve to be mentioned. First, all the data we obtained was limited to the information given in news reports which were not at all standardized across each variable. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind we had a substantial amount of missing data in the specification of incidents. Second, we have only investigated physical violence cases as they are more objectively evaluated, and more frequently reported. Thus, this study should not be generalized for all violence types. We aimed to minimize bias by strictly following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, though incidents that take place on the media generally tend to be excessive in nature.

This is a novel study as it gathers information regarding not only the distribution of physical violence incidents against physicians but also the reflections of those incidents among printed media. We have used an extensive database and a wide range of keywords minimalizing the possibility of missing any related news reports. This study presents an in-depth analysis of printed media reports regarding 11 years. Therefore, it provides an important resource to estimate the current course of events and the general outlook on physical violence against physicians.

Conclusion

Violence against physicians is a global problem which must be placed with utmost importance. Our study reveals that public awareness could be raised by the power of media. A total number of news reports evaluated is very few in comparison to violence acts towards physicians. Hence, further investigations regarding the impact of media on people should be made. It is also crucial to understand the real magnitude of the matter and the factors that have effect on it; such as the characteristics of assailants, susceptible conditions that lead to violence, and risk factors. The impacts of violence on HCWs and the public’s level of education on this regard must be determined and evaluated. Therefore not only analytical studies concerning the relationship between individual, environmental, and sociocultural risk factors and the characteristics of violence incidents should be conducted, but also qualitative studies regarding the personal opinions and suggestions of the physicians are necessary. Only then, effective strategies regarding prevention, punishment, education, and awareness might be achieved and executed.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Internally peer-reviewed.

Authorship Contributions: Concept: D.B., O.A.; Design: D.B., O.A.; Supervision: D.B., O.A.; Resource: D.B., F.K., İ.M.T.; Materials: D.B., F.K., İ.M.T.; Data: D.B., F.K., İ.M.T.; Analysis: D.B., F.K., İ.M.T.; Literature search: D.B., F.K., İ.M.T.; Writing: D.B., F.K., İ.M.T.; Critical revision: D.B., O.A.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berlanda S, Pedrazza M, Fraizzoli M, De Cordova F. Addressing risks of violence against healthcare staff in emergency departments:The effects of job satisfaction and attachment style. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5430870. doi: 10.1155/2019/5430870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Turki N, Afify AA, Alateeq M. Violence against health workers in family medicine centers. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:257–66. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S105407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar M, Verma M, Das T, Pardeshi G, Kishore J, Padmanandan A. A study of workplace violence experienced by doctors and associated risk factors in a tertiary care hospital of South Delhi, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:LC06–10. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22306.8895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen IH, Baste V, Rosta J, Aasland OG, Morken T. Changes in prevalence of workplace violence against doctors in all medical specialties in Norway between 1993 and 2014:A repeated cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017757. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baykan Z, Oktem IS, Cetinkaya F, Nacar M. Physician exposure to violence:A study performed in Turkey. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2015;21:291–7. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2015.1073008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaya S, Demir IB, Karsavuran S, Ürek D, Ilgün G. Violence against doctors and nurses in Hospitals in Turkey. J Forensic Nurs. 2016;12:26–34. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayranci U, Yenilmez C, Balci Y. Identification of violence in Turkish health care settings. J. Interpers. Violence. 2006;21:276–96. doi: 10.1177/0886260505282565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayram B, Çetin M, Oray NC, Can IO. Workplace violence against physicians in Turkey's emergency departments:A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanctôt N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers:A systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19:492–501. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun T, Gao L, Li F, Shi Y, Xie F, et al. Workplace violence, psychological stress, sleep quality and subjective health in Chinese doctors:A large cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z, Yan CM, Shi L, Mu HT, Li X, Li AQ, et al. Workplace violence against medical staff of Chinese children's hospitals:A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teoh RJ, Lu F, Zhang XQ. Workplace violence against healthcare professionals in China:A content analysis of media reports. Indian J Med Ethics. 2019;4:95–100. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2019.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu D, Hesketh T, Zhou XD. Media contribution to violence against health workers in China:A content analysis study of 124 online media reports. Lancet. 2015;386:S81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand T, Grover S, Kumar R, Kumar M, Ingle GK. Workplace violence against resident doctors in a tertiary care hospital in Delhi. Natl Med J India. 2016;29:344–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinar T, Acikel C, Pinar G, Karabulut E, Saygun M, Bariskin E, Guidotti TL, et al. Workplace violence in the health sector in Turkey:A national study. J Interpers Violence. 2017;32:2345–65. doi: 10.1177/0886260515591976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behnam M, Tillotson RD, Davis SM, Hobbs GR. Violence:Recognition, management, and prevention. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:565–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hills D, Joyce CM. Life satisfaction and self-rated health. 2014;201:535–40. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cetin M, Bicakci S, Canakci ME, Aydin MO, Bayram B. A critical appraisal of emergency medicine specialty training and resignation among residents in emergency medicine in Turkey. Emerg Med Int. 2019;2019:6197618. doi: 10.1155/2019/6197618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emam GH, Alimohammadi H, Sadrabad AZ, Hatamabadi H. Workplace violence against residents in emergency department and reasons for not reporting them;a cross sectional study. Emerg (Tehran, Iran) 2018;6:e7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hacer TY, Ali A. Burnout in physicians who are exposed to workplace violence. J Forensic Leg Med. 2020;69:101874. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabalci M. Education Level İndicators by Province and Regions. Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu, Ankara Bölge Müdürlüğü. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferri P, Silvestri M, Artoni C, Di Lorenzo R. Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital:A cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:263–75. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S114870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furin M, Eliseo LJ, Langlois B, Fernandez WG, Mitchell P, Dyer KS. Self-reported provider safety in an Urban emergency medical system. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:459–64. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.2.24124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowrouzi-Kia B, Chai E, Usuba K, Nowrouzi-Kia B, Casole J. Prevalence of Type II and Type III workplace violence against physicians:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2019;10:99–110. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2019.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turkish Ministry of Health. General Statistics in Medicine. Available from: https://rapor.saglik.gov.tr. Accessed March 8, 2022 .

- 27.Ayranci U. Violence toward health care workers in emergency departments in west Turkey. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:361–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]