ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an important human rights problem faced by one in three women worldwide. The aim of this study is to evaluate the demographic, trauma, and radiological characteristics of patients admitted to a tertiary emergency department due to IPV.

METHODS:

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education level, and marital status), trauma characteristics (severity, type, and location), radiological imaging findings (radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging) of patients diagnosed with IPV were evaluated.

RESULTS:

In the study, 1225 patients were evaluated, and 98.7% of them were women (mean age 35 [IQR: 17] years). Of the patients, 63.1% were high school and university graduates. The rate of married women was 74.6%. No relationship was found between gender, age, educational status, and marital status (p>0.05). Most of the traumas were minor (85.4%) and blunt (81.9%) trauma, and the most common types of trauma were kicking (49.9%) and punching (47.3%). It was found that the most frequently affected areas of the patients were the head and neck (76.7%), and the frequency of pelvic trauma was high in male patients (p<0.05). The most common bone fracture was nasal (40.5%) followed by ulna fractures (14.5%). The left-sided diaphyseal fractures were the most common in patients exposed to IPV. In our study, the frequency of mortality was 12.9%, and it was found to be significantly higher in males (p<0.05).

CONCLUSION:

Female patients are more frequently exposed to IPV. Specific injury characteristics can be detected in patients diagnosed with IPV and old fractures detected in these patients should alert the clinician about IPV.

Keywords: Abuse, emergency department, intimate partner violence, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a fundamental public health and human rights problem. IPV is defined as exposure to psychological, physical, or sexual assault by a current or former partner.[1,2] IPV victims often hesitate to explain that they live for reasons such as social stigmatization or fear of being re-exposed to violence by the abusing partner. Therefore, they are exposed to repetitive IPV, and this situation can be overlooked amid clinical confusion.[2]

The World Health Organization reported that one out of every three women worldwide has been subjected to physical or sexual violence at least once in their lifetime, and most of these cases are caused by their intimate partners.[3] Similarly, in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control has reported that one in four men was a victim of rape and physical abuse.[1]

IPV processes have been reported to lead to short- and long-term health consequences in victims, such as asthma-like attacks, irritable bowel syndrome, diabetes mellitus, chronic pain, memory loss, neurological symptoms, and poor reproductive health. IPV can also bring along psychological health problems such as emotional stress, suicide, and attempts.[1,4] Although imaging has increased the detection of IPV cases, it is being reported that the number of female cases elucidated is still less than the expected incidence.[5] The United States Preventive Services Task Force has notified clinicians that there will be large differences across the country if they request imaging from every woman of childbearing age as needed and refer those with imaging findings to support services.[6] The inability to elucidate these cases is explained by the idea that there are problems with the effective and supportive use of imaging and evaluation tools in clinical practice.[7]

It has been reported that radiologists play an important role in non-accidental child traumas and have potential importance in the detection of elderly abuse. It has also been reported in the literature that the imaging findings of IPV are reported, and functional imaging is used to evaluate IPV-related brain damage.[1,8]

We believe that IPV is related to imaging findings and that being radiologically defined of these findings will be potential determinants in the clinical process. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the demographic, trauma, and radiological characteristics of patients admitted to a tertiary emergency department (ED) for IPV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

The study was conducted retrospectively in cooperation with the emergency and the radiology department of the third step training and research hospital. The study was approved by the hospital’s local ethical committee (Ethical committee approval date and no.; February 17, 2020-82/05).

Selection of Participants

All patients above 18 years of age who were admitted to the ED for IPV between January 1, 2010, and January 1, 2020, were enrolled in the study. Patients who were assaulted by anybody other than the victims intimate partner and those whose radiological imaging studies (radiography, computed tomography [CT], and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) were not requested were excluded from the study.

Methods and Measurements

The information of patients diagnosed with assault (W50 and W51) on the relevant dates was evaluated using the International Classification of Diseases-10 diagnostic code in the hospital medical registration system. The medical records of patients were accessed through the hospital automation system and patient follow-up cards. Sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education level, and marital status), trauma characteristics (severity, type, and localization), and radiological imaging findings of patients diagnosed with IPV were evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using The SPSS package (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, Version 24.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of sociodemographic data was analyzed using a histogram. Quantitative variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR), qualitative variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare nonparametric variables. Pearson and Fisher’s Chi-square tests were used to analyze qualitative data. All analyses were performed at a 95% confidence interval and p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

IPV patients of 1225 were evaluated. Of the patients, 98.7% (n=1209) were female. The median age was 35 (IQR: 17) years. The median age of males and females exposed to IPV was found to be similar (p>0.05). Patients exposed to IPV are often high school graduates (34%); no relationship was found between gender and education level (p>0.05). It was found that the patients exposed to violence were often married (74.6%), there was no relationship between marital status and gender (p>0.05). It was detected that only 14.6% of the cases were suffering from major trauma and males were exposed to major trauma at a higher rate (p<0.05). It was determined that 81.9% of the patients were injured by blunt trauma and that more male patients were exposed to penetrating trauma (p<0.05). It was found that the patients were most frequently injured by kick and punch, females were injured more frequently by punch, and males were injured most frequently by gunshot wounds (p<0.05). The most common trauma localization was head and neck (76.7%), then upper extremity (51.6%). Pelvic injuries were more common in the males (p<0.05). The mortality rate in patients was 12.9%, and it was found to be significantly higher in males (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and trauma characteristics

| Total (n=1225) | Male (n=16) | Female (n=1209) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 35 (17) | 42.5 (22) | 35 (17) | 0.279 | |

| Education, n (%) | None | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (0.3) | >0.999 |

| Primary school | 172 (14) | 4 (25) | 168 (13.9) | ||

| Middle School | 277 (22.6) | 5 (31.3) | 272 (22.5) | ||

| High school | 416 (34) | 3 (18.8) | 413 (34.2) | ||

| University | 356 (29.1) | 4 (25) | 352 (29.1) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | Married | 914 (74.6) | 14 (87.5) | 900 (74.4) | 0.066 |

| Engaged | 137 (11.2) | 0 (0) | 137 (11.3) | ||

| Single | 174 (14.2) | 2 (12.5) | 172 (14.2) | ||

| Trauma severity, n (%) | Minor | 1046 (85.4) | 5 (31.3) | 1041 (86.1) | <0.001 |

| Major | 179 (14.6) | 11 (68.8) | 168 (13.9) | ||

| Trauma mechanism, n (%) | Blunt | 1003 (81.9) | 7 (43.8) | 996 (82.4) | 0.001 |

| Penetran | 205 (16.7) | 8 (50) | 197 (16.3) | ||

| Mixed | 17 (1.4) | 1 (6.3) | 16 (1.3) | ||

| Trauma type, n (%)* | Kicking | 608 (49.9) | 7 (43.8) | 601 (49.7) | 0.636* |

| Punching | 580 (47.3) | 0 | 580 (48) | <0.001 | |

| Slapping | 549 (44.8) | 6 (37.5) | 543 (44.9) | 0.554* | |

| Hitting with a blunt object | 457 (37.3) | 6 (37.5) | 451 (37.3) | 0.987* | |

| Pushing | 390 (31.8) | 7 (43.8) | 383 (31.7) | 0.303* | |

| Gun-shot wound | 145 (11.8) | 9 (56.3) | 136 (11.2) | <0.001 | |

| Hitting with a penetrating object | 77 (6.3) | 0 | 77 (6.4) | 0.618 | |

| Scratching | 54 (4.4) | 0 | 54 (4.5) | >0.999 | |

| Trauma localization, n (%)* | Head and neck | 940 (76.7) | 14 (87.5) | 926 (76.6) | 0.305 |

| Thorax | 282 (23) | 4 (25) | 278 (23) | 0.850 | |

| Abdomen | 214 (17.5) | 4 (25) | 213 (17.6) | 0.442 | |

| Pelvic | 4 (0.3) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (0.2) | <0.001 | |

| Upper extremity | 632 (51.6) | 11 (68.8) | 621 (51.4) | 0.167 | |

| Lower extremity | 359 (29.3) | 3 (18.8) | 356 (29.4) | 0.350 | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 158 (12.9) | 9 (56.3) | 149 (12.3) | <0.001 |

Frequency and percentage values show the ratio of the number of patients and the total number of patients.

Because some patients had more than one trauma, the total number of traumas was higher than the number of patients.

It was found that 401 patients (32.7%) had radiography. It was observed that 46 patients (3.8%) had more than 1 radiography. It was found that the MRI was applied to 39 (3.2%) patients. It was observed that 980 (80%) patients were performed CT and 43 (3.5%) patients were performed different or repeated CT examinations.

It was observed that CT was performed on 82.3% and different or repeated CT examinations were performed in 43 (3.5%) patients. Soft-tissue lesions without bone fracture (n=1007; 82.2%) were found the most common lesions in the patients and other lesion distributions are presented in Table 2. The most common bone fracture was in the nasal bone (40.5%). About 63.3% of the patients had head-and-neck fractures, 5.2% thorax, 0.2% pelvis, 26.5% upper extremity, and 9.5% lower extremity fractures. In upper extremity fractures, 230 (18.8%) were on the left, 135 (11%) were on the right, while 64 (5.2%) of the lower extremity fractures were on the left and 62 (5.1%) were on the right. The most common fractures of the upper extremity were in the ulna (14.5%) and the lower extremity in the tibia (5.9%) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Details of trauma localizations and soft tissue injury characteristics in imaging

| Trauma localization* | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Head and neck injury | 940 | 76.7 |

| Fracture (single and multiple) | 776 | 63.3 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 140 | 11.4 |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 116 | 9.5 |

| Epidural hemorrhage | 19 | 1.6 |

| Soft tissue lesion without a bone fracture | 656 | 53.6 |

| Thorax injury | 282 | 23 |

| Rib fracture | 62 | 5.1 |

| Pneumothorax | 58 | 4.7 |

| Hemothorax | 24 | 2 |

| Vascular injury | 13 | 1.1 |

| Pulmonary contusion | 7 | 0.6 |

| Vertebra fracture | 2 | 0.2 |

| Soft tissue lesion without a bone fracture | 152 | 12.4 |

| Abdomen injury | 214 | 17.5 |

| Free intraperitoneal fluid | 86 | 7 |

| Spleen | 46 | 3.8 |

| Small bowel | 32 | 2.6 |

| Liver | 12 | 1 |

| Large bowel | 2 | 0.2 |

| Soft tissue lesion without a bone fracture | 123 | 10 |

| Pelvic injury | 4 | 0.3 |

| Scrotal injury | 2 | 0.2 |

| Pelvic fracture | 2 | 0.2 |

| Soft tissue lesion without a bone fracture | 4 | 0.3 |

| Upper extremity injury | 632 | 51.6 |

| Fracture | 325 | 26.5 |

| Soft tissue lesion without a bone fracture | 561 | 45.8 |

| Lower extremity injury | 359 | 29.3 |

| Fracture | 116 | 9.5 |

| Soft tissue lesion without a bone fracture | 290 | 23.7 |

Frequency and percentage values show the ratio of the number of patients and the total number of patients.

Because some patients had more than one lesion, the total number of lesions was higher than the number of patients with lesions.

Table 3.

Details of bone fractures in imaging

| Fracture characteristics* | n (%) | Fracture characteristics* | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck fracture | 776 (63.3) | Upper extremity fracture | 325 (26.5) |

| Temporal fracture | 91 (7.4) | Scapula | 2 (0.2) |

| Nasal fracture | 496 (40.5) | Clavicle | 2 (0.2) |

| Maxilla fracture | 211 (17.2) | Isolated humerus fracture | 37 (3) |

| Vertebra fracture | 3 (0.2) | Isolated ulna fracture | 138 (11.3) |

| Mandibular fracture | 51 (4.2) | Isolated radius fracture | 80 (6.5) |

| Orbital fracture | 313 (25.6) | Ulna and radius fracture | 40 (3.3) |

| Zygoma fracture | 128 (10.4) | Isolated Phalanx | 26 (2.1) |

| Frontal fracture | 102 (8.3) | Scapula | 2 (0.2) |

| Parietal fracture | 16 (1.3) | Right | 0 |

| Occipital fracture | 3 (0.2) | Left | 2 (0.2) |

| Thorax fracture | 64 (5.2) | Clavicle | 2 (0.2) |

| Rib fracture | 62 (5.1) | Right | 2 (0.2) |

| Vertebra fracture | 2 (0.2) | Left | 0 |

| Pelvic fracture | 2 (0.2) | Diaphysis | 2 (0.2) |

| Pelvic fracture | 2 (0.2) | Metaphysis | 0 |

| Lower extremity fracture | 116 (9.5) | Proximal | 0 |

| Isolated femur fracture | 1 (0.1) | Distal | 0 |

| Isolated tibia fracture | 62 (5.1) | Midshaft | 2 (0.2) |

| Isolated fibula fracture | 43 (3.5) | Humerus fracture | 37 (3) |

| Tibia and fibula fracture | 10 (0.8) | Right | 9 (0.7) |

| Femur fracture | 1 (0.1) | Left | 28 (2.3) |

| Right | 0 | Diaphysis | 16 (1.3) |

| Left | 1 (0.1) | Metaphysis | 21 (1.7) |

| Diaphysis | 0 | Proximal | 9 (0.7) |

| Metaphysis | 1 (0.1) | Distal | 25 (2) |

| Proximal | 0 | Midshaft | 3 (0.2) |

| Distal | 1 (0.1) | Ulna fracture | 178 (14.5) |

| Midshaft | 0 | Right | 72 (5.9) |

| Tibia fracture | 72 (5.9) | Left | 106 (8.7) |

| Right | 37 (3.0) | Diaphysis | 97 (7.9) |

| Left | 35 (2.9) | Metaphysis | 81 (6.6) |

| Diaphysis | 28 (2.3) | Proximal | 26 (2.1) |

| Metaphysis | 44 (3.6) | Distal | 89 (7.3) |

| Proximal | 24 (2.0) | Midshaft | 63 (5.1) |

| Distal | 34 (2.8) | Radius fracture | 120 (9.8) |

| Midshaft | 14 (1.1) | Right | 32 (2.6) |

| Fibula fracture | 53 (4.3) | Left | 88 (7,2) |

| Right | 25 (2.0) | Diaphysis | 72 (5.9) |

| Left | 28 (2.3) | Metaphysis | 48 (3.9) |

| Diaphysis | 31 (2.5) | Proximal | 21 (1.6) |

| Metaphysis | 22 (1.8) | Distal | 63 (5.3) |

| Proximal | 17 (1.4) | Midshaft | 36 (2.9) |

| Distal | 18 (1.5) | Phalanx | 26 (2.1) |

| Midshaft | 18 (1.5) | Right | 20 (1.6) |

| Left | 6 (0.5) | ||

| Diaphysis | 16 (1.3) | ||

| Metaphysis | 10 (0.8) | ||

| Proximal | 9 (0.7) | ||

| Distal | 6 (0.5) | ||

| Midshaft | 11 (0.9) |

Frequency and percentage values show the ratio of the number of patients and the total number of patients. *Because some patients had more than one lesion, the total number of lesions was higher than the number of patients with lesions.

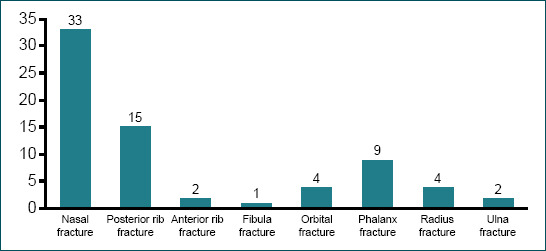

Old fractures were detected in the radiograph of 70 (5.7%) of the patients (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Old traumatic fractures localization.

DISCUSSION

Emergency physicians are in an important position to identify patients at risk of IPV. In the United States alone, it is evaluated that 4.5 million cases are exposed to IPV annually, only one-third of these cases seek medical help, and most of them are misdiagnosed.[9] Our study is one of the studies with the highest number of cases combining imaging findings associated with IPV and sociodemographic factors in patients applied to ED.

George et al.[1] have stated in their study that 96.2% of the patients exposed to IPV were females and the mean age of the patients was 34. In a similar study conducted by Choi et al.,[10] it was determined that 84% of the patients were female and that the population exposed to IPV is generally young adults. In our study, the median age of the cases was 35 years, and 98.7% of the cases were female, and no significant relationship was found between age and gender. We think that women are more subjected to violence because men are physically stronger than women, women are considered normal to be beaten in male-dominated societies, even they think that women will be disciplined by beating, and they see women as a burden and binding factor. Again, we think that due to these reasons and the negative elements that occur in both genders within the family over time, its transformation into verbal and physical abuse over time is more in the 3rd and 4th decades.

In the studies conducted, it has been stated that although IPV is seen in every part of the society, it is more common in groups with poor economic and social structure. It has been emphasized that men with low socioeconomic levels, unemployed, uneducated, and with psychological problems are more prone to IPV.[11,12] Choi et al.[10] have stated in their study that individuals exposed to IPV are mostly married, and their education level is at the secondary education level. Cunha and Gonçalves,[13] in their study, have emphasized that the duration of the marriage is an important criterion. Similar to the literature, the patients in our study were found to be married and have a high school education level. It was found that gender was independent of demographic data such as education and marital status. We are of the opinion that especially the financial and moral problems of married individuals over time result in harming each other in both genders. The level of education, on the other hand, may have established a ground for IPV as being directly related to materiality and indirectly related to social rights.

Although radiologists have been shown to play a key role in the diagnosis of child and elderly abuse,[2,14] fewer studies have been published to identify imaging characteristics specific to non-spontaneous trauma in adults with IPV.[2] George et al.,[1] in their study, where they have emphasized the role of radiology in imaging patients with IPV, have tried to draw a roadmap on how radiologists could work with other clinicians to identify IPV victims. When the number of imaging performed in IPV patients in the past 5 years and in their ED applications at the time of the event, it has been reported that 4 times more imaging were performed on these patients, and the majority of them were female with musculoskeletal system imaging.[2] In our study, the rate of radiography performed was approximately 33%, and the rate of repetitive radiography was approximately 4%. It was found that CT scans were performed in 80% of the patients, and CT imaging was performed again in 3.5% of the patients. We are of the opinion that the rate of CT scans is high due to the fact that all of the patients are forensic, the lesion is followed up due to the high rate of head trauma, and more than half of them have a brain and solid organ injuries.

Studies have stated that blunt trauma caused by an open hand or fist is the most common form of IPV.[9,15] Wu et al.[9] have associated this situation with the more comfortable use of the upper extremity of the individual who makes IPV. Most of the traumas were minor (85.4%) and blunt (81.9%) trauma, and the most common trauma types were kicking and punching. The frequency of minor injuries, penetrating injuries, and punch in female patients was significantly higher. In accordance with the previous studies, the most common form of trauma was found to be kicked and punch in our study. This may be related to the fact that the injuries of the individuals that will occur with such traumas do not cause serious lesions and are easy for the assailant. As a matter of fact, the high frequency of minor trauma in the cases supports our thesis.

Again, in many studies related to IPV, it has been stated that victims were injured mostly in the head, face, and neck region.[16–19] Sheridan and Nash[15] have reported that the incidence of injuries with slap or punch to the face was high in IPV cases. Although Wu et al.[9] have thought that upper extremity injuries were an important marker for IPV, they have stated that in cases where the patient defended himself/herself against the assailant with his/her arms or hands, he/she did not stop the attack before the damage occurred in the intended area such as the face and that maxillofacial trauma was more common. Muelleman et al.[19] and Petridou et al.[20] have stated in their studies that the frequency of extremity trauma was relatively lower in women. In our study, it was found that the most injured areas were the head and neck, in accordance with the literature. Considering that the most common form of trauma is fists and palms, we can explain why the frequency of head-and-neck injuries is high. In addition, we also believe that the head region is targeted for possible foreign body throwing in these patients.

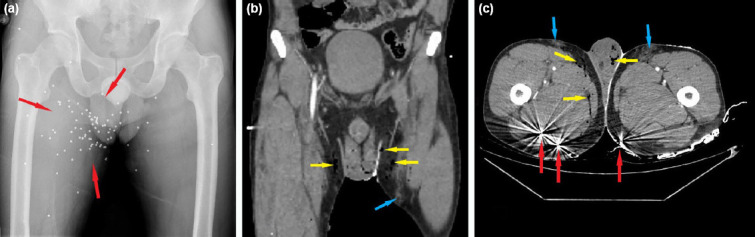

The frequency of pelvic injuries in male patients was found to be significantly higher (Fig. 2). The main reason why male patients are mostly injured in the pelvic area may be due to the fact that women think of this area as a weak point in men to survive the assault and also that women who have been sexually abused prefer this area to take revenge.

Figure 2.

An anteroposterior radiograph (a), coronal computed tomography section (b), and axial computed tomography section (c) of a 35-year-old man with pellet injury. There are multiple round opacities (red arrows) accompanied by hemorrhage (blue arrows) and emphysema (yellow arrows) in the right thigh and both hemiscrota.

In studies conducted in either adults or elderly population, while the frequency of soft-tissue trauma was in the first place, it has been stated that there were also fatal injuries that can lead to mortality.[1,2,14] These injuries include sprains, fractures/dislocations, burns, lacerations, stab wounds, chest contusions, and gastrointestinal pathologies.[9] Kavak and Özdemir,[14] in their study, have reported the soft-tissue injury rate in the elderly abuse as 54.3%, excluding fracture areas. George et al.[1] have reported that imaging findings associated with IPV include soft tissue and musculoskeletal injuries as well as obstetric and gynecological findings related to violence. Le et al.,[21] in their study evaluating domestic violence, have found maxillofacial fractures in 30% of 236 abused females and have reported that 40% of these facial fractures were nasal fractures. In this study, it has been stated that the frequency of fractures in the ribs and upper extremity was high. Sutherland et al.[22] and Tjaden and Thoennes[23] have reported in their study that the frequency of fractures due to IPV is approximately 11%. Murphy et al.[24] have reported posterior rib fractures, posterior lower extremity injuries, and injuries of the inner part of the thigh and the back or lower side (plantar) of the foot as indicators of physical abuse. It has been recognized that these areas are unlikely to be impact points in accidental injury. In our study, soft-tissue lesions without bone fracture were found the most common (Fig. 3), and the nasal fracture was detected as the most common fracture, consistent with the literature. We are of the opinion that an individual who performs IPV has made a habit of assaulting and causes crushing in the body and especially fractures in the nasal bone due to the frequent use of punches and slaps.

Figure 3.

Maxillofacial computed tomography section of a 30-year-old woman beaten by her husband. Severe soft-tissue injury without any bone fracture is evident in the left facial region (arrow).

For the long bones of the extremities, fractures in the middle and lower ends of the bones have been reported to be an indicator of abuse rather than accidents.[25] Distal radial metaphyseal fractures are much more common in accidental falls than distal ulnar diaphyseal fractures. It has been reported that distal ulnar diaphyseal fractures generally occur during the defense.[8,14] In our study, similar to the literature, it was found that an individual exposed to IPV mostly developed left and diaphyseal fractures. We think that the ulnar diaphyseal fractures caused by low-energy trauma suggest that it is the consequence of an assault (Fig. 4). The fact that most of the lesions of our patients are on the left supports this observation. This may be because the perpetrator uses his/her right side dominantly, and the victim resists with his/her left arm for protection.

Figure 4.

Anteroposterior left forearm radiograph of a 41-year-old woman who was attacked by her husband with a stick and whose arm was broken during self-defense. There is a fracture line at the distal ulnar diaphysis (arrow).

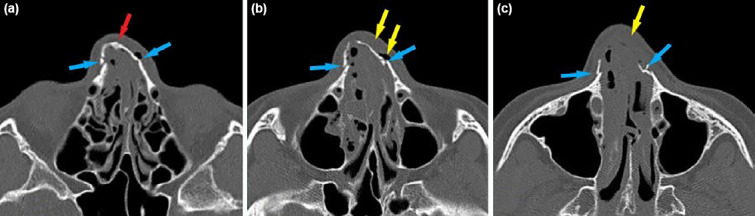

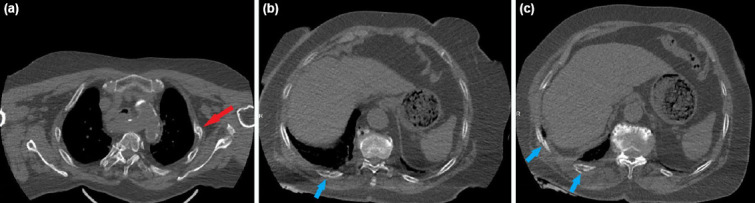

Soft-tissue injuries in the form of crushing or superficial injuries in different stages of recovery in different parts of the body have been reported in cases with the elderly abuse at a rate of up to 15%.[26] In different sources, it has been reported that most of these injuries are in the form of maxillofacial and upper extremity injuries that are in the recovery phase or bruising on the wrist and forearm.[14,25,27] Rosen et al.[25] have reported that radiologists do not look for old lesions in trauma patients; they often report lesions that are the subject of active complaints; Wong et al.[8] have stated that radiologists mention the old fractures very briefly in their reports or they do not care. Correcting these two factors will be extremely important in elucidating repetitive violence in either the elderly abuse or IPV cases. In our study, the rate of old fracture detection was 5.7%, and it was most common in the nasal and posterior rib (Figs. 5 and 6). We think that bruises and superficial scars in the body at different stages of recovery may also be descriptive for IPV patients, as detected in the elderly abuse. Although it may be accidental, finding old fractures in these two bones should remind doctors of repetitive trauma. We consider that old fractures are also important in the identification of IPV cases, similar to those in the elderly abuse.

Figure 5.

(a-c) Consecutive computed tomography sections of a 36-year-old woman’s nasal bone obtained after a physical fight with her partner. An old nasal fracture characterized by thickened sclerotic cortical bone is evident at the left nasal bone (red arrow). There are also multiple new fracture lines at both nasal bones (blue arrows) accompanied by emphysema and edema in soft tissues (yellow arrows).

Figure 6.

(a-c) Consecutive thoracic axial computed tomography sections of a 69-year-old male patient with multiple fractures on the posterior arches of his ribs as a result of his wife hitting repeatedly with a shovel. There is an old fracture (red arrow) as well as multiple new fractures (blue arrows).

If the victim tries to protect them because of their dependence on their partner, this may lead to the abusive relationship continuing, and the abuse will increase.[9] In a study, the records of the cases who died as a result of IPV have been examined, and it has been shown that most of the victims applied at least once due to trauma in their history.[28] In a study conducted in the United States, it has been reported that approximately 11% of all femicide were committed by their partner.[29] In a study conducted in England, 198 femicide over the age of 16 have been examined, and it has been found that 54% were killed by their spouse, ex-partner, or lover.[30] Savall et al.[31] have stated that although women were exposed to IPV more frequently, the severity of trauma experienced by men was higher. In our study, the frequency of mortality was 12.9%, and it was found to be significantly higher in males. We are of the opinion that the hidden IPV causes irreversible damages and mortality in the person as to its dose and severity increase over time. The reason for the higher mortality of male patients may be thought that the only way to get rid of the abuser is to kill the abuser, as the woman does not want to be exposed to constant trauma after a while and cannot find help she demands.

The first limitation of the study is the lack of a control group of trauma cases without IPV. This fact limits the precise definition of IPV-associated lesions. The second limitation of the study is that it has a retrospective, non-blind design performed on patients derived from single-center ED data. Therefore, some patient information such as ethnicity, number of previous emergency visits, and lesions other than lesions in the files could not be recorded. Conversely, it may have led to a more aggressive review to identify patients’ acute and subacute injuries associated with IPV.

Conclusion

Radiology applications have unique opportunities to develop clinical and imaging pathways to help identify IPV victims. The collaboration of emergency medicine physicians and radiologists can reduce overlook for IPV patients and prevent further harm.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: This study was approved by the Dışkapı Yıldırım Beyazıt Training and Research Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Date: 17.02.2020, Decision No: 82/05).

Peer-review: Internally peer-reviewed.

Authorship Contributions: Concept: N.K., R.P.K.; Design: N.K., R.P.K.; Supervision: N.K., R.P.K.; Resource: N.K., R.P.K., M.Ö., M.S., N.E.; Data: N.K., R.P.K., M.Ö., M.S., N.E.; Analysis: N.K., R.P.K., M.Ö., M.S., N.E., A.S.; Literature search: N.K., R.P.K., M.Ö., M.S., N.E., A.S.; Writing: N.K.; Critical revision: N.K., R.P.K., M.Ö., M.S.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.George E, Phillips CH, Shah N, Lewis-O'Connor A, Rosner B, Stoklosa HM, et al. Radiologic findings in intimate partner violence. Radiology. 2019;291:62–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019180801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores EJ, Narayan AK. The role of radiology in intimate partner violence. Radiology. 2019;291:70–1. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Violence against Women. World Health Organization. 2017. [Accessed Aug 02, 2020]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/.

- 4.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence:Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, Davidson LL, Feder G, Taft A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD007007. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007007.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Preventive Services Task Force. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults:US preventive services task force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dicola D, Spaar E. Intimate partner violence. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:646–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong NZ, Rosen T, Sanchez AM, Bloemen EM, Mennitt KW, Hentel K, et al. Imaging findings in elder abuse:A role for radiologists in detection. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2017;68:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu V, Huff H, Bhandari M. Pattern of physical injury associated with intimate partner violence in women presenting to the emergency department:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11:71–82. doi: 10.1177/1524838010367503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi AW, Wong JY, Lo RT, Chan PY, Wong JK, Lau CL, et al. Intimate partner violence victims'acceptance and refusal of on-site counseling in emergency departments:Predictors of help-seeking behavior explored through a 5-year medical chart review. Prev Med. 2018;108:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–80. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali TS, Asad N, Mogren I, Krantz G. Intimate partner violence in urban Pakistan:Prevalence, frequency, and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2011;3:105–15. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S17016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunha OS, Gonçalves RA. Predictors of intimate partner homicide in a sample of portuguese male domestic offenders. J Interpers Violence. 2019;34:2573–98. doi: 10.1177/0886260516662304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavak RP, Özdemir M. Radiological appearance of physical elder abuse. Eur Geriatr Med. 2019;10:871–8. doi: 10.1007/s41999-019-00246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheridan DJ, Nash KR. Acute injury patterns of intimate partner violence victims. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:281–9. doi: 10.1177/1524838007303504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhandari M, Dosanjh S, Tornetta P, 3rd, Matthews D. Violence Against Women Health Research Collaborative. Musculoskeletal manifestations of physical abuse after intimate partner violence. J Trauma. 2006;61:1473–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196419.36019.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perciaccante VJ, Carey JW, Susarla SM, Dodson TB. Markers for intimate partner violence in the emergency department setting. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spedding RL, McWilliams M, McNicholl BP, Dearden CH. Markers for domestic violence in women. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:400–2. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.6.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muelleman RL, Lenaghan PA, Pakieser RA. Battered women:Injury locations and types. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:486–92. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petridou E, Browne A, Lichter E, Dedoukou X, Alexe D, Dessypris N. What distinguishes unintentional injuries from injuries due to intimate partner violence:A study in Greek ambulatory care settings. Inj Prev. 2002;8:197–201. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le BT, Dierks EJ, Ueeck BA, Homer LD, Potter BF. Maxillofacial injuries associated with domestic violence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1277–83. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.27490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland CA, Bybee DI, Sullivan CM. Beyond bruises and broken bones:The joint effects of stress and injuries on battered women's health. Am J Community Psychol. 2002;30:609–36. doi: 10.1023/A:1016317130710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence and Consequences of Violence against Women Survey. Washington DC: Department of Justice, Publication Number NCJ; 2000. p. 183781. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy K, Waa S, Jaffer H, Sauter A, Chan A. A literature review of findings in physical elder abuse. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013;64:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen T, Bloemen EM, Harpe J, Sanchez AM, Mennitt KW, McCarthy TJ, et al. Radiologists'training, experience, and attitudes about elder abuse detection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:1210–4. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans CS, Hunold KM, Rosen T, Platts-Mills TF. Diagnosis of elder abuse in U. S. emergency departments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:91–7. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiglesworth A, Austin R, Corona M, Schneider D, Liao S, Gibbs L, et al. Bruising as a marker of physical elder abuse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1191–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadman MC, Muelleman RL. Domestic violence homicides:ED use before victimization. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:689–91. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholls A, Gibson L, McKenna K, Gray M, Wielandt T. Assessment of standing in Functional Capacity Evaluations:An exploration of methods used by a sample of occupational therapists. Work. 2011;38:145–53. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2011-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall P. Intimate violence 2009/10 BCS. Homicides, Firearm Offences and Intimate Violence 2009/10. In: Smith K, editor. Supplementary Volume 2 to Crime in England and Wales. 2nd ed. London, England: Home Office Statistics; 2011. pp. 68–95. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savall F, Lechevalier A, Hérin F, Vergnault M, Telmon N, Bartoli C. A ten-year experience of physical Intimate partner violence (IPV) in a French forensic unit. J Forensic Leg Med. 2017;46:12–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]