Abstract

Background

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux (GOR) is characterised by the regurgitation of gastric contents into the oesophagus. GOR is a common presentation in infancy, both in primary and secondary care, affecting approximately 50% of infants under three months old. The natural history of GOR in infancy is generally of a self‐limiting condition that improves with age, but older children and children with co‐existing medical conditions can have more protracted symptoms. The distinction between gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and GOR is debated. Current National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines define GORD as GOR causing symptoms severe enough to merit treatment. This is an update of a review first published in 2014.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological treatments for GOR in infants and children.

Search methods

For this update, we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science up to 17 September 2022. We also searched for ongoing trials in clinical trials registries, contacted experts in the field, and searched the reference lists of trials and reviews for any additional trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared any currently‐available pharmacological treatment for GOR in children with placebo or another medication. We excluded studies assessing dietary management of GORD and studies of thickened feeds. We included studies in infants and children up to 16 years old.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodology expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 36 RCTs involving 2251 children and infants. We were able to extract summary data from 14 RCTs; the remaining trials had insufficient data for extraction. We were unable to pool results in a meta‐analysis due to methodological differences in the included studies (including heterogeneous outcomes, study populations, and study design).

We present the results in two groups by age: infants up to 12 months old, and children aged 12 months to 16 years old.

Infants

Omeprazole versus placebo: there is no clear effect on symptoms from omeprazole. One study (30 infants; very low‐certainty evidence) showed cry/fuss time in infants aged three to 12 months had altered from 246 ± 105 minutes/day at baseline (mean +/‐ standard deviation (SD)) to 191 ± 120 minutes/day in the omeprazole group and from 287 ± 132 minutes/day to 201 ± 100 minutes/day in the placebo group (mean difference (MD) 10 minutes/day lower (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐89.1 to 69.1)). The reflux index changed in the omeprazole group from 9.9 ± 5.8% in 24 hours to 1.0 ± 1.3% and in the placebo group from 7.2 ± 6.0% to 5.3 ± 4.9% in 24 hours (MD 7% lower, 95% CI ‐4.7 to ‐9.3).

Omeprazole versus ranitidine: one study (76 infants; very low‐certainty evidence) showed omeprazole may or may not provide symptomatic benefit equivalent to ranitidine. Symptom scores in the omeprazole group changed from 51.9 ± 5.4 to 2.4 ± 1.2, and in the ranitidine group from 47 ± 5.6 to 2.5 ± 0.6 after two weeks: MD ‐4.97 (95% CI ‐7.33 to ‐2.61).

Esomeprazole versus placebo: esomeprazole appeared to show no additional reduction in the number of GORD symptoms compared to placebo (1 study, 52 neonates; very low‐certainty evidence): both the esomeprazole group (184.7 ± 78.5 to 156.7 ± 75.1) and placebo group (183.1 ± 77.5 to 158.3 ± 75.9) improved: MD ‐3.2 (95% CI ‐4.6 to ‐1.8).

Children

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at different doses may provide little to no symptomatic and endoscopic benefit.

Rabeprazole given at different doses (0.5 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg) may provide similar symptom improvement (127 children in total; very low‐certainty evidence). In the lower‐dose group (0.5 mg/kg), symptom scores improved in both a low‐weight group of children (< 15 kg) (mean ‐10.6 ± SD 11.13) and a high‐weight group of children (> 15 kg) (mean ‐13.6 ± 13.1). In the higher‐dose groups (1 mg/kg), scores improved in the low‐weight (‐9 ± 11.2) and higher‐weight groups (‐8.3 ± 9.2). For the higher‐weight group, symptom score mean difference between the two different dosing regimens was 2.3 (95% CI ‐2 to 6.6), and for the lower‐weight group, symptom score MD was 4.6 (95% CI ‐2.9 to 12).

Pantoprazole: pantoprazole may or may not improve symptom scores at 0.3 mg/kg, 0.6 mg/kg, and 1.2 mg/kg pantoprazole in children aged one to five years by week eight, with no difference between 0.3 mg/kg and 1.2 mg/kg dosing (0.3 mg/kg mean −2.4 ± 1.7; 1.2 mg/kg −1.7 ± 1.2: MD 0.7 (95% CI ‐0.4 to 1.8)) (one study, 60 children; very low‐certainty evidence).

There were insufficient summary data to assess other medications.

Authors' conclusions

There is very low‐certainty evidence about symptom improvements and changes in pH indices for infants. There are no summary data for endoscopic changes. Medications may or may not provide a benefit (based on very low‐certainty evidence) for infants whose symptoms remain bothersome, despite nonmedical interventions or parental reassurance. If a medication is required, there is no clear evidence based on summary data for omeprazole, esomeprazole (in neonates), H₂antagonists, and alginates for symptom improvements (very low‐certainty evidence). Further studies with longer follow‐up are needed.

In older children with GORD, in studies with summary data extracted, there is very low‐certainty evidence that PPIs (rabeprazole and pantoprazole) may or may not improve GORD outcomes. No robust data exist for other medications.

Further RCT evidence is required in all areas, including subgroups (preterm babies and children with neurodisabilities).

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Humans; Infant; Infant, Newborn; Esomeprazole; Gastroesophageal Reflux; Gastroesophageal Reflux/complications; Gastroesophageal Reflux/drug therapy; Omeprazole; Pantoprazole; Proton Pump Inhibitors; Proton Pump Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Rabeprazole; Ranitidine

Plain language summary

Medicines for children with reflux

Review question

What is the best and safest treatment for babies and children with gastro‐oesophageal reflux?

Key messages:

‐ the evidence for medications for babies with gastro‐oesophageal reflux/reflux disease is very uncertain;

‐ for children with gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease, the evidence is very uncertain regarding the effects of proton pump inhibitors. There was no adequate evidence to draw conclusions regarding other medications.

What is gastro‐oesophageal reflux?

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux happens when stomach contents come back up into the oesophagus (food pipe). Most babies (under 1 year) grow out of reflux symptoms, but does medicine help? Children (older than 1 year) can have reflux just like adults. Reflux can be normal ('physiological reflux'), but in babies and children, it can cause symptoms, including pain or weight loss, as the oesophagus becomes inflamed (oesophagitis). Bothersome symptoms of reflux are called 'gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease' (GORD).

How is gastro‐oesophageal reflux treated?

Medicines can thicken the stomach contents (alginates), neutralise stomach acid (ranitidine, omeprazole, lansoprazole), or help the stomach to empty faster (domperidone, erythromycin).

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to learn the best way to reduce reflux in babies and children. We wanted to see if medicines help infants and children to feel better (symptom scores), heal the oesophagus (which is checked by using endoscopy, where a tiny camera is put down the oesophagus), or lower the time the oesophagus is exposed to stomach acid. We also investigated whether the medicines were safe by considering the harmful or unwanted effects reported in the studies.

What did we do?

We searched for studies testing gastro‐oesophageal reflux medicines in babies and children. We included all studies comparing these medicines, or comparing them to an inactive medicine (placebo). We assessed results which are important to doctors, nurses, and parents, and performed our own analysis of the results. We rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 36 suitable studies (involving 2251 babies and children), conducted worldwide, with most in the USA. The largest study recruited 268 babies, the smallest, 16 children. Fifteen studies compared an active medicine to placebo; 8 compared one active medication to another; and 11 studies gave the same medication at different doses. We found useable outcome information in 14 of the 36 studies. The remaining studies either did not report outcomes we were interested in or did not report them in a way we could analyse. We could not combine the results of any studies because they were too different (in terms of how long they followed participants up and the outcomes they investigated) to use in a meaningful way.

Key results

Babies. There is no clear effect on symptoms or measured acidity (one measure is reflux index, which is the percentage of time in 24 hours the oesophagus is exposed to stomach acid) between babies given omeprazole or placebo. One study (30 babies) showed cry/fuss time went down from 287 to 201 minutes/day in the placebo group and 246 to 191 minutes/day in the omeprazole group. Reflux index changed in the omeprazole group from 9.9% to 1.0% in 24 hours, and in the placebo group from 7.2% to 5.3%. One study (76 babies) showed that omeprazole and ranitidine may have a similar benefit for symptoms after 2 weeks: symptom scores (higher scores mean worse symptoms) in the omeprazole group dropped from 51.9 to 2.4, and in the ranitidine group, from 47 to 2.5. In one study of 52 newborn babies, esomeprazole appeared to show no reduction in the number of symptoms (184.7 to 156.7) compared to placebo (183.1 to 158.3). None of the studies reported harmful events or results about changes to babies' oesophaguses.

Children. In children older than 1 year of age, no studies assessed medical treatment versus placebo. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which block stomach acid production, at different doses may provide little to no improvements in symptoms or oesophagus healing. In one study (127 children), both lower‐weight and higher‐weight children given rabeprazole at lower and higher doses had both minimal – probably unimportant – changes in symptom scores and endoscopic scores (which indicate whether healing of the oesophagus has occurred). Pantoprazole may or may not improve symptom scores in children aged 1 to 5 years by week 8: there was no difference between lower and higher dosing in one study (60 children). Studies investigating other medications did not report enough information for us to assess their results properly.

Quality of the evidence

We are not confident in the evidence, which was mainly based on single studies with few babies and children. Several studies had pharmaceutical company help with manuscript writing. The question of how best to treat children with disabilities, and whether any PPIs are better than other medicines remain. The evidence is current to 17 September 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Omeprazole compared to placebo for GORD in infants.

| Omeprazole compared to placebo for GORD in infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants with GORD Setting: outpatients Intervention: omeprazole Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with omeprazole | |||||

| Improvement in symptoms in infants assessed with: cry/fuss diary (minutes/day) Follow‐up: mean 2 weeks | The mean improvement in symptoms in infants was ‐66 minutes/day | MD 10 minutes/day lower (89.1 lower to 69.1 higher) | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Cry/fuss time in infants between 3 and 12 months of age (mean 5.4 months) improved from 246 ± 105 minutes/day at baseline (mean +/‐ SD) to 191 ± 120 minutes/day in the omeprazole group and from 287 ± 132 minutes/day to 201 ± 100 minutes/day in the placebo group (mean difference (MD) 10 minutes/day lower (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐89.1 to 69.1)) |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | There were no reports of adverse events in either the omeprazole or placebo group | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Improvement in pH metrics in infants assessed with: reflux index Follow‐up: mean 2 weeks | The mean improvement in pH metrics in infants was 1.9 % of time in 24 hours | MD 7% of time in 24 hours lower (4.66 lower to 9.34 lower) | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | In the omeprazole group, the reflux index improved from 9.9 ± 5.8% in 24 hours to 1.0 ± 1.3% in 24 hours. In the placebo group, the reflux index improved from 7.2 ± 6.0% in 24 hours to 5.3 ± 4.9% in 24 hours. |

| Endoscopic metrics ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | There were no data to assess this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429021146969853213. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: outcomes were assessed with behaviour diary (potential for recall bias) and visual analogue score (potential for parental observer bias). There were concerns that some of these infants may not have had significant endoscopic or reflux index changes at inclusion. North American Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) guidance in place at the time considered reflux index > 10% to be pathological in infants, and no evidence of reflux oesophagitis was seen (erosions or ulcers) at entry endoscopy. The inclusion criteria considered loss of vascular pattern or friability enough for inclusion. Only seven infants had both endoscopic changes and reflux index > 5%. With these concerns, we have downgraded the evidence by one step. bImprecision: for Moore 2003, there was a wide confidence interval crossing the clinical decision threshold and only 15 infants in each group so we have downgraded the evidence by two steps. cRisk of bias: there were concerns that some of these infants may not have had significant endoscopic or reflux index changes at inclusion. NASPGHAN guidance in place at the time considered reflux index > 10% to be pathological in infants, and no evidence of reflux oesophagitis was seen (erosions or ulcers) at entry endoscopy. The inclusion criteria considered loss of vascular pattern or friability enough for inclusion. Only seven infants had both endoscopic changes and reflux index.

Summary of findings 2. Omeprazole compared to ranitidine for GORD in infants.

| Omeprazole compared to ranitidine for GORD in infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: GORD in infants Setting: outpatients Intervention: omeprazole Comparison: ranitidine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with ranitidine | Risk with omeprazole | |||||

| Improvement in symptoms in infants assessed with: weekly gastro‐oesophageal reflux score (WGSS) Follow‐up: mean 2 weeks | The mean improvement in symptoms in infants was ‐44.5 points | MD 4.97 points lower (2.47 lower to 7.33 lower) | ‐ | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Omeprazole (0.5 mg/kg/day) appears to provide some symptomatic benefit in infants between 2 and 12 months old, with improved scores after 2 weeks (51.93 ± 5.42 to 2.43 ± 1.15) equivalent to ranitidine (2 to 4 mg/kg/day) with scores improving (47 ± 5.6 to 2.47 ± 0.58): no differences between omeprazole and ranitidine were noted: MD ‐4.97 (95% CI ‐2.47 to ‐7.33). |

| Adverse events in infants ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome | |||

| Improvement in pH metrics in infants ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome | |||

| Improvement in endoscopic findings in infants ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429020868699799221. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by two steps due to issues with blinding (performance bias) as omeprazole was delivered as a capsule and ranitidine as a syrup so parents would be aware which medication was being offered. In addition, 16 infants were lost to follow‐up (attrition bias), severe pneumonia, premature discontinued drugs, and parental issues with the questionnaire bImprecision: as the confidence intervals do not overlap the clinical decision threshold between recommending and not recommending treatment, and the study had very small numbers, we downgraded the certainty of evidence by two steps (very serious), but the certainty of evidence was already very low.

Summary of findings 3. Esomeprazole compared to placebo for GORD in infants.

| Esomeprazole compared to placebo for GORD in infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: GORD in infants Setting: inpatients in 3 neonatal intensive care units Intervention: esomeprazole Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with esomeprazole | |||||

| Improvement in symptoms and signs in infants assessed with: total number of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) symptoms Follow‐up: mean 2 weeks | The mean improvement in symptoms and signs in infants was ‐24.5 episodes | MD 3.2 episodes fewer (4.6 fewer to 1.8 fewer) | ‐ | 52 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c,d | Included data from premature babies to 1 m corrected gestational age. No data in older infants. For total number of GORD symptoms (from video monitoring) and GORD‐related signs (from cardiorespiratory monitoring), the esomeprazole group improved from baseline 184.7 (78.5) to 156.7 (75.1) and placebo group improved from 183.1 (77.5) to 158.3 (75.9). |

| Adverse events ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | It was not possible to extract summary data, although there were no reported differences between the placebo and esomeprazole groups. |

| pH indices ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome | |||

| Endoscopic metrics ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429020489057615413. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by one step as the study was terminated early due to poor recruitment (the power calculation estimated needing 38 neonates in each group). bIndirectness: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by one step as the population studied (neonates) is only a part of the population under assessment (infants). cImprecision: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by two steps due to small numbers and wide confidence intervals crossing the clinical decision threshold. dPublication bias: this single study was industry‐funded, with support for manuscript‐writing, but the certainty of evidence was not downgraded by one step, as already at 'very low'

Summary of findings 4. Rabeprazole at higher doses (1 mg/kg) compared to rabeprazole at lower doses (0.5 mg/kg) for GORD in children over 1 year of age.

| Rabeprazole at higher doses (1 mg/kg) compared to rabeprazole at lower doses (0.5 mg/kg) for GORD in children over 1 year of age | ||||||

| Patient or population: GORD in children over 1 year of age Setting: outpatients Intervention: rabeprazole at higher doses (1 mg/kg) Comparison: rabeprazole at lower doses (0.5 mg/kg) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with rabeprazole at lower doses (0.5 mg/kg) | Risk with rabeprazole at higher doses (1 mg/kg) | |||||

| Improvement in symptoms assessed with: 'Total GORD Symptoms and Severity' score Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean improvement in symptoms was ‐9.9 points | MD 2.3 points higher (2 lower to 6.6 higher) | ‐ | 127 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Rabeprazole at 0.5 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg may provide similar symptom improvement: in the 0.5 mg/kg group, symptom score improved in both the low‐weight (< 15 kg) (n = 21 mean ‐10.6 ± SD 11.13)) and high‐weight (> 15 kg) groups (n = 44 mean ‐13.6 ± 13.1). In the 1 mg/kg group, scores improved in the low‐weight (n = 19, ‐9 ± 11.2)) and higher‐weight groups (n = 43, ‐8.3 ± 9.2). For the higher‐weight group, MD 2.3 (95% CI ‐2 to 6.6), and low‐weight group: 0.5 mg/kg vs 1 mg/kg: MD 4.6 (95% CI ‐2.9 to 12). |

| Adverse events assessed with: parent‐reported events | Rabeprazole at 0.5 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg may lead to some adverse events: 95 (84%) children had adverse events, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bronchopneumonia, gastroenteritis, cough, and choking. | 127 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | There was no difference between the groups. | ||

| Improvement in endoscopic appearances assessed with: Hetzel‐Dent score Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean improvement in endoscopic appearances was ‐1.4 points | MD 0.1 points higher (0.23 lower to 0.43 higher) | ‐ | 127 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | In the 0.5 mg/kg group, endoscopic appearances improved in both the low‐weight (‐1.4 ± 1.06) and higher‐weight groups (‐1.2 ± 0.75). In the 1 mg/kg group, endoscopic appearances also improved in the low‐weight (‐1.1 ± 0.72) and high‐weight groups (‐1.0 ± 0.85). In the low‐weight group: 0.5 mg/kg vs 1 mg/kg: MD 0.30 (95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.87) and in the higher‐weight group MD 0.1 (95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.43). |

| pH indices ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome. | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429021824944230742. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by one step for selection bias: 30% of children had already received proton pump inhibitors, 15% H2 antagonists, and 2% prokinetics. 15% of participants had also withdrawn. bImprecision: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by one step as the wide confidence intervals crossed the clinical decision threshold. cPublication bias: the certainty of evidence was downgraded by one step as this was a single study and was industry‐funded, with assistance in manuscript preparation, and authors were employed by a pharmaceutical company. The study design involved the same medication at different doses which is less clinically useful than comparison to placebo or an alternative medication. We do not have other studies to assess whether this would have had a material impact.

Summary of findings 5. Pantoprazole in higher doses (1.2 mg/kg) compared to pantoprazole at lower doses (0.3 mg/kg) for GORD in children over 1 year of age.

| Pantoprazole in higher doses (1.2 mg/kg) compared to pantoprazole at lower doses (0.3 mg/kg) for GORD in children over 1 year of age | ||||||

| Patient or population: GORD in children over 1 year of age Setting: outpatients Intervention: pantoprazole in higher doses (1.2 mg/kg) Comparison: pantoprazole at lower doses (0.3 mg/kg) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with pantoprazole at lower doses (0.3 mg/kg) | Risk with Pantoprazole in higher doses (1.2 mg/kg) | |||||

| Improvement in symptoms assessed with: weekly gastro‐oesophageal reflux score (WGSS) Follow‐up: mean 8 weeks | The mean improvement in symptoms was ‐2.37 points | MD 0.7 points higher (0.4 lower to 1.8 higher) | ‐ | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Pantoprazole appears to improve symptoms at 0.3 mg/kg, 0.6 mg/kg, and 1.2 mg/kg pantoprazole in 60 children aged 1 to 5 years. Symptom scores improved from baseline to week 8 (0.3 mg/kg MD ‐2.4, 95% CI ‐3.2 to ‐1.5; 1.2 mg/kg ‐1.7, 95% CI ‐2.9 to ‐0.39). There was no difference between 0.3 mg/kg and 1.2 mg/kg dosing: MD 0.7 (95% CI ‐0.4 to 1.8). Individual symptoms (abdominal pain, burping, heartburn, pain after eating and difficulty swallowing) improved in all groups after 8 weeks. |

| Adverse events assessed with: individual symptom reporting Follow‐up: 8 weeks | Pantoprazole at all doses investigated may lead to adverse events: in the 0.3 mg/kg group, 1 child developed diarrhoea and nappy rash; in the 0.6 mg/kg group, 1 child had sleep disturbance and 1 developed abdominal pain; and in the 1.2 mg/kg group, 1 child had rectal bleeding. | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | There was no difference between the groups. | ||

| Improvement in pH indices ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome. | |||

| Improvement in endoscopic metrics ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | No data were available for this outcome. | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429032441167302611. | ||||||

aRisk of bias: we downgraded the certainty of evidence by one step as no comment was made about blinding and randomisation technique. bImprecision: we downgraded the certainty of evidence due to the small sample size, which would not meet the optimal information size, and confidence intervals that cross the decision‐making threshold. We would have downgraded by two steps but the certainty of evidence was already 'very low'. cPublication bias: we downgraded the certainty of evidence by one step as this study was industry‐funded with support with manuscript writing. The study design involved the same medication at different doses which is less clinically useful than comparison to placebo or an alternative medication. It is difficult to estimate the degree of effect given other studies were not available to compare.

Background

Description of the condition

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux (GOR) occurs when gastric contents come back up into the oesophagus (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018). GOR is a very common presentation, both in primary and secondary care settings. Symptoms of GOR can affect approximately 50% of infants aged one to three months old (Miyazawa 2002; Nelson 1997). The natural history of GOR is generally of improvement with age, with less than 5% to 10% of children with vomiting or regurgitation in infancy continuing to have symptoms after the age of 12 to 14 months (Campanozzi 2009; Martin 2002). This is due to a combination of growth in length of the oesophagus, a more upright posture, increased tone of the lower oesophageal sphincter, and a more solid diet.

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is defined as "GOR associated with bothersome symptoms or complications" (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018; Sherman 2009). Sherman and colleagues caution that this definition is complicated by unreliable reporting of symptoms in children under eight years of age (Sherman 2009). Gastrointestinal sequelae include oesophagitis, haematemesis, oesophageal stricture formation, and Barrett's oesophagitis. Extraintestinal sequelae can include acute life‐threatening events, apnoea, chronic otitis media, sinusitis, secondary anaemia, and chronic respiratory disease (chronic wheezing/coughing or aspiration), as well as failure to thrive. The presence of severe oesophagitis has historically been shown to predict the need for surgical reconstruction (Hyams 1988).

GOR is distinguished from vomiting physiologically by the absence of (1) a central nervous system emetic reflex, (2) retrograde upper intestinal contractions, (3) nausea, and (4) retching. GOR is generally characterised as effortless and non‐projectile, although it may be forceful in infants (Sherman 2009). Other conditions, such as rumination syndrome, are distinguished by the absence of nighttime symptoms, and features such as early satiety and bloating may point to functional dyspepsia (Hyams 2016).

Children with certain predisposing conditions are more prone to severe GORD. These conditions include neurological impairment (e.g. cerebral palsy), repaired oesophageal atresia or congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and chronic lung disease.

Diagnosis of physiological or functional GOR (i.e. reflux symptoms that are likely to improve with gut maturation) in infants is usually made based on the symptoms alone, avoiding the need for expensive and possibly harmful investigations. Investigations to assess the severity of GORD, or in cases where GOR cannot be diagnosed on clinical grounds, include 24‐hour oesophageal pH monitoring, which can be combined with impedance monitoring, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, scintigraphy, or oesophageal manometry. All have been shown to correlate poorly with symptomatology, and may not accurately predict the degree of improvement with treatment (Augood 2003; NICE 2019).

Clinical symptoms are commonly scored and reported individually. These symptoms include:

number of vomiting episodes, back arching, regurgitation, failure to thrive, feeding difficulties, and abdominal pain in infants;

heartburn, epigastric pain, and regurgitation symptoms in older children.

Common scoring systems include the Paediatric Gastro‐oesophageal Symptom Questionnaire (PGSQ) for older children (Kleinman 2011), the GORD Assessment of Symptoms in Pediatrics Questionnaire (GASP‐Q) for younger children (Fitzgerald 2003), and the Infant Gastro‐oesophageal Reflux Questionnaire Revised (I‐GERQ‐R) for infants (Orenstein 2010).

Normal gastric juices are acidic in nature, with a pH of approximately 1 to 3. The pH scale goes from 1 (strongly acidic) through 7 (neutral), to 14 (strongly alkaline).

Investigations to assess disease severity include:

pH‐impedance indices over 24 hours, including: reflux index on pH probe (percentage of time that oesophageal pH < 4 in 24 hours); number of acid reflux/impedance episodes; and time length of reflux episodes where oesophageal pH is less than 4;

endoscopic findings, including macroscopic appearance of oesophagus on endoscopy, and histological appearances.

Consensus exists that there are insufficient data to recommend histology as a tool to diagnose or exclude GORD in children, but that histology is useful in confirming the presence of oesophagitis and ruling out other conditions, such as eosinophilic oesophagitis, Barrett's oesophagus, Crohn's disease, infection, and graft‐versus‐host disease (NICE 2019). Histological scoring scales (e.g. the Hetzel‐Dent classification) are also commonly utilised to help assess improvement (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018).

Description of the intervention

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs, such as omeprazole and lansoprazole, are a group of drugs that irreversibly inactivate H+/K+ ATPase, in the parietal cells of the stomach. There are five PPIs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in adults: omeprazole (since 1988), lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole (the pure S‐isomer of omeprazole). The current National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend only a two‐week trial of a PPI or a histamine receptor antagonist (H₂RA) for infants whose symptoms fail to improve with nonmedical interventions (NICE 2019). Omeprazole is licensed for use in children over one year of age in the UK, with a half‐life of one hour, but due to the permanent receptor block, the effect can last for five to seven days. The dose range is 5 mg to 10 mg daily in infants, 10 mg to 20 mg daily in young children, and 20 mg to 40 mg daily in older children and adolescents. Lansoprazole is only recommended by the British National Formulary for children when treatment with the available formulations of omeprazole is unsuitable (BNFc 2021). It is used in doses of 7.5 mg to 15 mg in young children, and 15 mg to 30 mg in older children. The average elimination half‐life is 1.5 hours in infants and young children. The inhibition of acid secretion is about 50% of maximum at 24 hours and the duration of action is approximately 72 hours (Ward 2013). Esomeprazole is also licensed for GORD: for children aged one to 11 years with a body‐weight of 10 kg to 19 kg, 10 mg once daily; for children aged one to 11 years with a body‐weight of 20 kg and above, 10 mg to 20 mg once daily; for children aged 12 to 17 years, 20 mg to 40 mg once daily, and a maintenance dose of generally 20 mg daily. Pantoprazole and rabeprazole are not currently licensed for use in children.

Gastric pH provides some protection against infection in children. Thus, there is evidence that potentiating the hypochlorhydria (low levels of stomach acid) in neonates further with PPIs can result in bacterial overgrowth (De Bruyne 2018). Increases in respiratory infections in critically‐ill inpatients have been identified, but in infants and children who are otherwise well, no clear ill effects have been demonstrated from this overgrowth. A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) alert in 2012 highlighted that PPIs used for longer than three months may be associated with hypomagnesaemia (especially in those on therapy lasting for more than five years), and a possible increased risk of fractures (Fleishmann 2021; MHRA 2012). Since then, concerns have been raised about hypergastrinaemia (but the risk of cancer is not thought to be increased), Clostridioides difficile colitis, vitamin B12 deficiency (due to atrophic gastritis and hypochlorhydria, which produce bacterial overgrowth promoting increased digestion of cobalamin), and acute interstitial nephritis (a hypersensitivity reaction that can occur within days to 18 months of starting treatment and resolves on discontinuing the PPI) (BNFc 2021; NICE 2019). There have been a handful of cases reported of PPI‐induced systemic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and significant drug interactions (itraconazole, ketoconazole, isoniazid, oral iron supplements) (Schoenfeld 2016). PPIs are metabolised by the cytochrome P450 system in the liver and interactions include those medications that inhibit or enhance cytochrome P450 metabolism (listed in BNFc 2021).

Histamine (H₂) receptor antagonists (H2RAs)

The most commonly used H2RA is ranitidine, which competitively blocks selective histamine receptors. Ranitidine is metabolised in the liver and renally excreted with a half‐life of two to four hours and length of action of 12 to 24 hours. Ranitidine is well‐tolerated and has a low incidence of side effects; these commonly include fatigue, dizziness, and diarrhoea (Tighe 2009). It also affects metabolism of other drugs by the cytochrome P450 system (BNFc 2021). Ranitidine has been withdrawn worldwide due to concerns regarding a low level of impurity of N‐nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) (MHRA 2019). Cimetidine is rarely used clinically because of concerns about its greater effects on the cytochrome P450, which cause multiple drug interactions, as well as its interference with vitamin D metabolism and endocrine function. Famotidine is a recently‐developed H₂ antagonist not commonly used in children but with similar pharmacodynamics to ranitidine. Tachyphylaxis from H₂ antagonists has been reported (McRorie 2014).

Magnesium hydroxide and aluminium hydroxide (MHAH)

Magnesium hydroxide and aluminium hydroxide reduce gastric pH and are commercially available as Maalox. Aluminium should be avoided in chronic use, especially in infants and children with chronic renal failure, due to the risk of aluminium accumulation.

Prokinetics

Domperidone is a dopamine‐receptor (D‐2) blocker that has relatively few side effects, but case reports of extrapyramidal side effects exist (Franckx 1984; Shafrir 1985), and there is concern about the risk of cardiac side effects (EMA 2014b). Its use has declined except in specialist indications, since the publication of NICE guidance (NICE 2019). Current advice is to not use it in children with co‐existing cardiac disease or in those taking CYP3A4 inhibitors, and not to exceed a daily dose of 30 mg/day in children over 12 years old and 250 micrograms/kg three times a day in younger children (EMA 2014b). Domperidone is no longer marketed in the USA (Bashashati 2016), but can be used as an investigational new drug and should not be used for nausea and vomiting for more than one week.

Erythromycin is a macrolide antibiotic; its use as a prokinetic is as an unlicensed indication (BNFc 2021).

Metoclopramide has been the subject of an FDA 'black box' warning (FDA 2009). In August 2013, the European Medicines Agency released a statement that the risk of neurological adverse events (such as short‐term extrapyramidal disorders and tardive dyskinesia) with metoclopramide outweighed the benefit, when taken for a prolonged period at a high dose (EMA 2014a). Metoclopramide has also been assessed in a separate Cochrane Review (Craig 2004), so we did not review the associated literature for metoclopramide as it is not used to treat reflux in children, given the adverse event profile and NICE guidance (NICE 2019).

At its peak use, cisapride was prescribed to over 36 million children worldwide for GOR (Vandenplas 1999). However, concerns about the effect of cisapride in prolonging the QT interval led to its removal from general paediatric use (Com Safety Med 2000). A Cochrane Review found that there was no clear evidence that cisapride reduces symptoms of GOR, and found evidence of substantial publication bias favouring studies showing a positive effect of cisapride (Augood 2003). Given the known risks of toxicity and its suspension of manufacture, further trials of cisapride are unlikely.

Quince syrup (heated extract of Cydonia oblonga Mill.) belongs to the rose family (Rosacea) as a traditional Persian medicine to treat GORD (Zohalinezhad 2015). It is unlicensed in the UK.

Alginates

Compound alginate preparations differ from other alginate preparations, which can also contain sodium bicarbonate or potassium bicarbonate (BNFc 2021).

Caution should be used with alginates that contain aluminium (see below), and in children with vomiting or diarrhoea, or children at risk of intestinal obstruction (Gaviscon Product Information 2021). In children whose feeds are already thickened (e.g. Enfamil AR/SMA Staydown), coexistent Gaviscon Infant could potentially cause intestinal obstruction (Keady 2007). Some alginate preparations contain sodium: for example, Gaviscon Infant contains 0.92 mmol Na+/dose, which should be considered if a child’s sodium intake needs to be monitored with caution (e.g. renal impairment, congestive cardiac failure, preterm infants, or children with diarrhoea and vomiting) (BNFc 2021). Gaviscon Infant has changed to become aluminium‐free, with different proportions of alginate, and other forms are now available (Gastrotuss and Refluxsan Nipio). Alginates for infants are generally prescribed at up to six doses per day with half a dual sachet in formula bottles of less than 210 mL and one dual sachet in formula bottles of more than 210 mL of milk. Breastfed babies have a dose mixed with expressed breast milk and given before or with a breastfeed by syringe.

Two other Cochrane Reviews have assessed thickened feeds (Craig 2004; Kwok 2017).

Antispasmodics

Baclofen is primarily an antispasmodic acting on gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, commonly used in children with neurodisability, such as cerebral palsy (Omari 2006). It is not licensed for children with GORD (BNFc 2021).

Conservative options

These include reassurance of parents, and positioning of the baby to reduce gastro‐oesophageal reflux, through the effect of gravity on gastric contents. This can include elevating the head of the cot or basket in which the baby is placed to sleep, or keeping the baby upright after a feed.

Altering the feed's consistency can be achieved with feed thickeners (e.g. with rice starch/carob bean gum) and may reduce the reflux of gastric contents with increased viscosity. Some feeds are manufactured with a thickening agent added. Weaning also has a similar effect by increasing the viscosity of gastric contents, and gastro‐oesophageal reflux is known to improve with weaning. We have considered compound alginates in this review, but not other feed‐thickeners, which are assessed elsewhere (Craig 2004; Kwok 2017).

Changes in feeding can also improve GOR. For breastfed babies, a breastfeeding assessment by health professionals experienced in breastfeeding is recommended initially, then elimination of cow's milk from the maternal diet can be trialled. For formula‐fed infants, after assessing for and correcting overfeeding, clinicians can consider recommendations supporting two to four weeks of a protein hydrolysate or amino acid‐based formula (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018; NICE 2019).

Surgical options

Surgery is used to limit GORD. The most common strategy is a Nissen's fundoplication involving a 360º wrap (Hassall 2005). This aims to combine antireflux factors, including creation of a high pressure zone at the distal oesophagus and recreation of the diaphragmatic crural mechanism. However, underlying dysmotility may persist and retching may continue as a prominent feature. Comparisons of these techniques are considered elsewhere (NICE 2019). We have not assessed conservative and surgical strategies in this Cochrane Review, which seeks to assess medical treatments, to better inform medical practitioners (GPs/paediatricians). Surgery relates to a small minority of children with gastro‐oesophageal reflux and is beyond the scope of this review.

How the intervention might work

Pharmacological treatments work by altering the gastric pH (e.g. PPIs, H₂ antagonists) and reducing the acidity of refluxate, by promoting gut motility (prokinetics), or by altering the viscosity of refluxate (alginates). Pharmacological treatments are considered if nonmedical measures have been ineffective. Dosing, metabolism interactions, and associated adverse events are described above.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs irreversibly inactivate H+/K+ ATPase, at the level of the parietal cell membrane transporter. This increases the pH of gastric contents and decreases the total volume of gastric secretion. Of the five PPIs approved by the FDA, three are licensed in the UK for children: omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole. PPIs were the subject of a 'Pediatric Written Request' (PWR) made by the FDA to improve our knowledge of PPIs in children and infants. There is good clinical experience with PPIs in children, and an excellent evidence‐base of efficacy in adults (NICE 2019).

H₂ receptor antagonists (H2RAs)

H₂ antagonists also aim to increase the pH of gastric contents in children, and there is good clinical experience with H₂ antagonists in infants, children, and adults (NICE 2019).

Magnesium hydroxide and aluminium hydroxide (MHAH)

MHAH is designed to reduce gastric acid, and forms water as a by‐product. Its use in children is unlicensed.

Prokinetics

Prokinetics are considered when GOR fails to improve with conservative measures. There are several classes of drugs designed to increase gastrointestinal motility.

Domperidone acts to increase motility and gastric emptying through acting on dopamine receptors and decreases post‐prandial reflux time (Franckx 1984; Shafrir 1985). Domperidone had been commonly used in clinical practice, either as part of empirical medical therapy of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease or if delayed gastric emptying has been demonstrated on a barium swallow or milk scan.

Erythromycin binds to motilin receptors to promote peristalsis and gastric emptying, to decrease post‐prandial reflux time. Its use as a prokinetic is unlicensed.

Metoclopramide has also been assessed in a separate Cochrane Review (Craig 2004), so we did not review the associated literature for metoclopramide as it is not used to treat reflux in children, given the adverse event profile and NICE guidance (NICE 2019).

Cisapride is a gastro‐oesophageal prokinetic agent which stimulates motility in the gastrointestinal tract by increasing acetylcholine release in the myenteric plexus, controlling smooth muscle. As cisapride has been the subject of a separate Cochrane Review (Augood 2003), and is now no longer manufactured, we have not reviewed the literature for this drug.

Quince syrup has ulcer‐healing properties and is thought to increase the lower oesophageal sphincter tone (Zohalinezhad 2015).

Alginates

Compound alginate preparations prevent reflux in infants by increasing the viscosity of gastric contents (BNFc 2021). This contrasts with other Gaviscon preparations, which can also contain sodium bicarbonate/potassium bicarbonate that – in the presence of gastric acid – forms a gel in which carbon dioxide (derived from the breakdown of bicarbonate) is trapped. This 'foam raft' floats on top of the gastric contents and is designed to neutralise gastric acid (providing symptomatic relief), to thicken the feed (to reduce reflux), and to reduce oesophageal irritation (Mandel 2000).

Sodium and magnesium alginate (Gaviscon Infant) is a thickener, and other forms are now available (Gastrotuss and Refluxsan Nipio).

Other thickening agents, such as carob bean gum (Carobel), have been assessed separately (Craig 2004; Kwok 2017). Current NICE guidance recommends discontinuing pre‐thickened formulas if alginates are trialled (NICE 2019).

Antispasmodics

Baclofen has been used to treat co‐existing reflux by aiming to improve the incoordination of the lower oesophageal sphincter, reducing the number of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) (Omari 2006). It is not part of clinical GORD consensus guidelines (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux in children is a common condition. Healthcare professionals frequently use pharmacological treatment of this condition for symptom relief. New studies have been published since the original version of this review (Tighe 2014), and new medicines to treat gastro‐oesophageal reflux are available. Thus, an up‐to‐date synthesis of the evidence, including the current balance of benefits and harms of these treatments, is required.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological treatments for GOR in infants and children.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for inclusion.

Types of participants

We included all children (aged 0 to 16 years) with "GOR associated with bothersome symptoms or complications" (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018; see also Sherman 2009).

We predefined two groups organised by age: infants up to 12 months old, and children aged 12 months to 16 years old. We included studies assessing preterm neonates and children with a neurodisability.

Types of interventions

We included all currently available medical treatments for gastro‐oesophageal reflux in children.

We considered all RCTs that compared a medication for GOR with a placebo or another medication. We imposed no restrictions on dosage, frequency, or duration of pharmacological treatment.

We attempted comparisons of all active treatments versus placebo, by treatment class:

proton pump inhibitors (PPIs: omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole) versus placebo;

H₂ antagonists (ranitidine, famotidine, cimetidine) versus placebo;

prokinetics (domperidone, erythromycin, bethanechol) versus placebo;

compound alginate preparations versus placebo

sucralfate versus placebo.

We included studies assessing quince syrup, a traditional Persian medicine to treat GOR. We outline the evidence base, but note that quince syrup is not currently a prescribable medicine in many countries, including the United Kingdom.

We excluded studies assessing metoclopramide, thickened feeds, or using thickened feeds as a comparator. (In a 2004 Cochrane Review, Craig and colleagues assessed metoclopramide and thickened feeds for GOR in children under two years of age (Craig 2004); this review has since been withdrawn.) We excluded studies employing conservative treatment and surgical techniques for GOR, as well as studies assessing dietary management of GORD. We excluded studies assessing pharmacological treatments for GORD in people with coexistent conditions, such as tracheo‐oesophageal fistula (TOF) or asthma, that predispose them to GORD, to avoid heterogeneity between participants.

Types of outcome measures

To make this update as robust as possible, and to assist the potential for meta‐analysis, we selected the same outcome measures in this updated review as in the previous version (Tighe 2014). We included all reported outcomes that are likely to be meaningful to clinicians making medical decisions about treating gastro‐oesophageal reflux. We included all time points for assessments. We identified studies with very short follow‐up periods (fewer than two weeks) as a potential source of bias.

We did not exclude studies based on outcomes measured. However, we excluded studies assessing purely pharmacokinetic outcomes or taste, as these were not considered as primary or secondary outcome measures of interest. Nevertheless, to exclude outcome bias, we contacted corresponding authors of such trials to establish if there were any relevant data that had not been published. In cases of uncertainty, we contacted corresponding authors for clarification.

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was improvement in clinical symptoms, which was usually assessed through questionnaires completed by parents and childcare providers. The symptoms monitored included:

number of vomiting episodes (continuous data);

episodes of back arching (continuous data);

number of regurgitation episodes (continuous data);

failure to thrive (binary outcome);

feeding difficulties (binary outcome);

abdominal pain in infants (continuous data).

In older children, the number of episodes of heartburn, epigastric pain, or regurgitation (continuous data) were again assessed through questionnaires completed by participants, parents, and health professionals. These included, for example, the Paediatric Gastro‐oesophageal Symptom Questionnaire (PGSQ) and the Infant Gastro‐oesophageal Reflux Questionnaire–Revised (I‐GER‐Q), which were completed daily by parents and health professionals to provide quantitative data through validated symptom scores.

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcomes were: adverse effects, 24‐hour pH‐impedance indices, and endoscopic metrics.

Adverse effects

We explored all studies for any adverse effects, as defined by the Medicines Health Regulation Authority (MHRA 2012). In cases of uncertainty, we contacted corresponding authors for clarification. This exploratory approach aimed to identify unanticipated and rare adverse effects of an intervention and to look for data on possible associations between an intervention and a list of observed adverse events, to add to existing safety profiles. We assessed and reported adverse effects, and studies reporting the absence of adverse effects without separate data extraction, in line with Cochrane guidance (Higgins 2022).

24‐hour pH‐impedance indices

Reflux monitoring measures the amount of reflux in the oesophagus during a 24‐hour period. The test is carried out by placing a catheter in the oesophagus. These indices assess:

improvement in the reflux index (continuous data);

number and duration of reflux episodes on a 24‐hour pH‐impedance probe (continuous data);

results of non‐acid impedance studies (continuous data).

Endoscopic metrics

Improvement of oesophagitis on endoscopy (visual appearance – this can be a binary outcome or continuous data if scored (e.g. Hetzel‐Dent classification));

Histology (continuous data).

Different grading scales currently exist for classifying macroscopic appearances of the oesophagus, but no one grading scale has been demonstrated to show superior validity to the alternatives. We considered the description of histological changes, and histological scoring scales, and where relevant to help clinicians, we describe useful findings below. However, we did not include histological data in the summary of findings tables.

The number of children within a study population who failed to improve and required fundoplication was considered a potential secondary outcome (binary outcome).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 17 September 2022:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via Ovid Evidence‐Based Medicine Reviews Database (EBMR) (from inception to 2022) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946 to 17 September 2022) (Appendix 2);

Embase via Ovid (from 1974 to 17 September 2022) (Appendix 3);

Science Citation Index via Web of Science (from inception to 17 September 2022) (Appendix 4).

We searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.ClinicalTrials.gov).

We developed this search strategy with assistance from the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Gut Group.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all eligible studies and relevant reviews identified by the search and published within the past five years for possible references to RCTs. We also contacted experts in the field for any additional trials.

Adverse outcomes

We did not conduct a separate search for adverse events.

Language

We did not restrict our searches by language, and translated papers as necessary.

Data collection and analysis

We used Review Manager 5.4 and RevMan Web for data collection and analysis (RevMan 2019; RevMan Web 2022).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MT, IL) downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a reference management database and removed duplicates. Four review authors (MT, IL, EA, RMB) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion. We retrieved the full‐text reports/publications and independently applied the eligibility criteria to the full texts, identified studies for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, when required, through consulting a fifth review author (NAA).

We listed studies that initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but that we later excluded in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, with the reasons for their exclusion. We collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We also provided any information we could obtain about ongoing studies. We entered studies that were only in abstract form, or were only identified in the ISRCTN register into the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (MT, IL, EA) independently extracted the data using a robust data extraction form (utilised in the first review), checked and entered the data into RevMan 5.4/RevMan Web, analysed the data, and highlighted any discrepancies, with statistician supervision (AH). RMB supervised data collection and acted as arbiter for any disagreements. If studies had insufficient data, we did not extract summary data. We collected and archived data in a format to facilitate future access and data sharing. Where statistical analyses were not possible (or were inappropriate), we provided a descriptive summary. We looked at all studies, performing further analysis of those employing an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis where such information existed, and have included single forest plots of studies with summary data extracted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

As in the original review, we have described each study in a risk of bias table, and addressed the following issues, which may be associated with biased estimates of treatment effect: recruitment strategy, random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011). We commented specifically on:

the method of generation of the randomisation sequence;

the method of allocation concealment – it is considered 'adequate' if the assignment could not be foreseen, and should be independent of and remote from the investigators;

who was blinded and not blinded (participants, clinicians, outcome assessors) if this was appropriate (up to and after the point of treatment allocation);

how many participants were lost to follow‐up in each arm, and whether reasons for losses were adequately reported;

whether all participants were analysed in the groups to which they were originally randomised (intention‐to‐treat principle).

We also reported on:

the baseline assessment of the participants for age, sex, and duration of symptoms, if suggestive of bias between the groups;

whether outcome measures were described and their assessment was standardised;

the use and appropriateness of statistical analyses, where we could not extract tabulated data from the original publication.

Measures of treatment effect

The outcomes described above yielded both continuous and dichotomous data.

Clinical symptoms produced continuous data (e.g. number of vomiting episodes), yielding outcomes described as the mean difference (MD) and standardised mean difference (SMD). We extracted continuous data (e.g. reflux index) for summary data: we used means and standard deviations (SDs) to derive a mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using a fixed‐effect model.

The latest guidelines of the North American Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) do not define normal values for pH‐metry and pH‐impedance (NASPGHAN‐ESPGHAN guidelines 2018). We therefore continued to treat reflux index as continuous data but removed consideration of whether baseline values were normal or abnormal (which had been discussed in the previous version of this review), and included any improvement/non‐improvement in values compared to the other agent or dose being tested, expressed as MD ± 95% CI.

Dichotomous data, such as improvement/non‐improvement in endoscopic appearance, produced outcome data we presented as risk ratios. For studies of a single pharmacological agent (e.g. omeprazole) versus either placebo or a different drug, if sufficient trials were available and participant characteristics were clinically similar, we planned to conduct meta‐analyses of primary and secondary outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

We considered unit of analysis issues for any included trials with multiple treatment groups and cluster‐randomised designs. We considered cross‐over trials for inclusion and assessed only the first stage of therapy prior to cross‐over, but commented on results obtained after cross‐over if clinically relevant. We also considered issues arising from multiple observations for the same outcome (e.g. repeated pH‐impedance measurements), and planned to consult the Cochrane Gut group if clarification was required. For multi‐arm studies, we analysed multiple intervention groups appropriately to prevent arbitrary omission of relevant groups or double‐counting of participants.

Dealing with missing data

Where we were uncertain about the specifics of a trial pertinent to analysis, we contacted trial authors or sponsors of studies published from 2014 to 2022 to request missing data or clarification. We detailed authors' and sponsors' contribution in Characteristics of included studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We screened studies to assess clinical heterogeneity and planned subgroup analyses if appropriate, reporting on the extent of any heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Where we found evidence of significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) in summary data extraction, we downgraded the evidence certainty.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed selective reporting of results by comparing (where available) the outcomes listed in trials' original protocols to those reported in the final papers. We also searched clinical trials registries for details of the included trials. We contacted the primary investigator(s) of included trials to determine whether they were aware of any relevant unpublished data. We aimed to identify publication bias with the construction of funnel plots (Page 2020). However, insufficient trials were eligible for inclusion in the current version of the review. We plan to undertake this analysis in future if we can include more trials.

Data synthesis

We were unable to combine studies meaningfully due to the heterogeneity of studies in terms of outcomes, comparisons, and populations. For continuous measurements, we had planned to use weighted mean differences to pool results from studies using a common measurement scale. Where studies used different measurement scales, we planned to pool standardised mean differences. Instead, we have presented difference in means and 95% confidence intervals for individual studies and summary effects, using the following order: Population > Comparison > Outcome. We assessed all individual treatments separately, given the individual study differences and heterogeneity in study design. We considered combining data – for example, on high‐dose versus low‐dose proton pump inhibitors (please see Effects of interventions) – to attempt to increase the population size on which conclusions were based, only where similar outcomes in similar participants were assessed. However, we were unable to undertake this method due to the heterogeneity of study methodology. Due to the number of summary of finding tables, we limited our assessment of quince syrup, as it is not a prescribable medicine. We have not included quince syrup in the summary of findings tables, nor assessed the certainty of evidence for this intervention.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We addressed subgroup analysis in two ways. First, we have distinguished between infants (up to 12 months in age) and children (one to 16 years in age) throughout the review. These subgroups have different GOR characteristics. For example, infants with symptomatic gastro‐oesophageal reflux have different symptoms from older children (who are generally on a more solid diet, and are upright). Some treatments, such as alginates, are mainly used in the infant cohort.

Secondly, we looked for studies evaluating specific subgroups: (1) preterm infants, as this group of babies can be problematic to assess and often have empirical treatment for common symptoms (e.g. apnoeas and bradycardias) that can be caused by GORD, but are more commonly caused by other issues associated with prematurity; and (2) children with neurodisability, who often have considerable gut dysmotility, and are often on long‐term antireflux therapy. The results are outlined within Effects of interventions.

Where we found substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) between studies for the primary outcome, we explored the reasons for heterogeneity (including severity of reflux, demographic differences (age and comorbidity) within the age subgroups, having considered varying outcomes, different comparison agents (same drug, different dosing)) and downgraded the evidence certainty. As it was inappropriate to pool the data because of clinical or statistical heterogeneity, which we discuss in Overall completeness and applicability of evidence, we did not conduct meta‐analysis. There were insufficient studies within other specific subgroups (preterm infants and children within neurodisability) to consider heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

In this review update, we could not undertake meta‐analysis due to the heterogeneity of the included studies' populations, comparisons, and outcomes. Thus, sensitivity analysis was not required. In future updates of the review, if meta‐analysis is possible, we plan to undertake sensitivity analysis to explore whether a 12‐month age threshold for subgroups influences meta‐analytic robustness. We plan to integrate these findings into the results and conclusions. Additionally, if there are sufficient data in future updates of the review, we plan to explore whether endoscopic metrics, pH indices, and symptomatic outcomes are affected by either endoscopic descriptors (such as erosive or non‐erosive oesophagitis) or severity markers on 24‐hour pH‐impedance monitoring (such as reflux index). Other possible sensitivity analyses will depend on the type of meta‐analysis possible.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Two authors (MT, EA) independently used the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of evidence within the text of the review. We resolved any disagreements through discussion, involving all review authors if a disagreement could not be resolved.

Our summary of findings tables prioritise comparisons and outcomes that will be of use to decision‐makers. We deferred the creation of summary of findings tables for treatments that are not currently available by prescription to future review updates. All review author reviewed the GRADE considerations in assessing the certainty of evidence (Schünemann 2013), and integrated judgements into the summary of findings tables.

All review authors agreed prior to data collection that the summary of findings tables should distinguish results by age (infants: 0 to 12 months; and children: aged 1 to 16 years old). The tables present these outcomes: symptoms, adverse events, pH impedance indices, and endoscopic metrics. We provide clear rationales where we downgraded evidence according to GRADE criteria.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

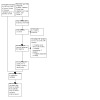

The first version of this review included 24 studies (Tighe 2014). In the September 2022 update searches, we identified 1427 records through electronic database searches and supplemental search methods. After the removal of duplicates, 1034 records remained. At this stage, we discarded 978 records as clearly irrelevant. We screened the full‐text publications of 54 studies (56 records). We excluded 40 studies (42 records) and listed two studies as 'awaiting classification.' We identified 12 new studies for inclusion. Thus, in this updated version, we have included a total of 36 RCTs assessing 2251 participants. We identified no ongoing studies (see Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

Included studies

We present the main characteristics of the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design

Of the 36 RCTs, most (31) were of parallel‐group design (Azizollahi 2016; Baker 2010; Ballengee 2018; Bines 1992; Borrelli 2002; Buts 1987; Carroccio 1994; Cresi 2008; Cucchiara 1984; Cucchiara 1993; Davidson 2013; Famouri 2017; Forbes 1986; Gilger 2006; Gunesekaran 2003; Haddad 2013; Kierkus 2011; Loots 2014; Miller 1999; Naeimi 2019; Omari 2006; Omari 2007; Orenstein 2008; Pfefferkorn 2006; Simeone 1997; Tolia 2006; Tolia 2010a; Tolia 2010b; Tsou 2006; Ummarino 2015; Zohalinezhad 2015); two were cross‐over studies (Baldassarre 2020; Moore 2003), two were withdrawal studies (Hussain 2014; Orenstein 2002), and one had a more complex design (Del Buono 2005). Twenty‐two studies (61%) enroled more than 40 participants (Azizollahi 2016; Baker 2010; Baldassarre 2020; Carroccio 1994; Cucchiara 1984; Davidson 2013; Famouri 2017; Gilger 2006; Gunesekaran 2003; Haddad 2013; Hussain 2014; Loots 2014; Miller 1999; Naeimi 2019; Omari 2007; Orenstein 2008; Tolia 2006; Tolia 2010a; Tolia 2010b; Tsou 2006; Ummarino 2015; Zohalinezhad 2015), and 14 studies enroled fewer than 40 participants (Ballengee 2018; Bines 1992; Borrelli 2002; Buts 1987; Cresi 2008; Cucchiara 1993; Del Buono 2005; Forbes 1986; Kierkus 2011; Moore 2003; Omari 2006; World Bank 2022; Pfefferkorn 2006; Simeone 1997). The largest study enroled 268 participants (Hussain 2014).

Fifteen studies were multicentre (Baker 2010; Baldassarre 2020; Davidson 2013; Gilger 2006; Gunesekaran 2003; Haddad 2013; Hussain 2014; Loots 2014; Miller 1999; Orenstein 2002; Orenstein 2008; Tolia 2006; Tolia 2010a; Tolia 2010b; Tsou 2006) and 21 were single‐centre (Azizollahi 2016; Ballengee 2018; Bines 1992; Borrelli 2002; Buts 1987; Carroccio 1994; Cresi 2008; Cucchiara 1984; Cucchiara 1993; Del Buono 2005; Famouri 2017; Forbes 1986; Kierkus 2011; Moore 2003; Naeimi 2019; Omari 2006; Omari 2007; Pfefferkorn 2006; Simeone 1997; Ummarino 2015; Zohalinezhad 2015). Seventeen studies had a placebo‐controlled arm (Ballengee 2018; Bines 1992; Buts 1987; Carroccio 1994; Cresi 2008; Davidson 2013; Del Buono 2005; Famouri 2017; Forbes 1986; Hussain 2014; Loots 2014; Miller 1999; Moore 2003; Omari 2006; Orenstein 2002; Orenstein 2008; Simeone 1997). Ten studies compared the active medication to a comparator medication (Azizollahi 2016; Baldassarre 2020; Borrelli 2002; Carroccio 1994; Cucchiara 1984; Cucchiara 1993; Naeimi 2019; Pfefferkorn 2006; Ummarino 2015; Zohalinezhad 2015), and 10 studies used the same medication at different doses (Baker 2010; Gilger 2006; Tolia 2010b; Gunesekaran 2003; Haddad 2013; Kierkus 2011; Tolia 2006; Tolia 2010a; Tolia 2010b; Tsou 2006). One study compared improvements on the active medication to baseline (Omari 2006). All the studies were conducted on outpatients except Cresi 2008 and Davidson 2013 which were conducted on inpatients in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). All bar four of the studies were conducted in high‐income countries: Azizollahi 2016, Famouri 2017, Naeimi 2019, and Zohalinezhad 2015 were conducted in Iran, a lower‐middle income country (World Bank 2022).

Participants

Nineteen studies assessed infants only, six studies assessed infants and children, and 11 assessed children aged one year or older. Of the studies that assessed infants only, 14 included infants with symptomatic GORD (Azizollahi 2016; Baldassarre 2020; Bines 1992; Cresi 2008; Davidson 2013; Del Buono 2005; Famouri 2017; Forbes 1986; Hussain 2014; Loots 2014; Miller 1999; Orenstein 2002; Orenstein 2008; Ummarino 2015), four studies included infants with symptoms and signs of GORD on 24‐hour pH/impedance monitoring (Ballengee 2018; Kierkus 2011; Moore 2003; Omari 2007); one study included infants with endoscopic changes (Pfefferkorn 2006); and one study included infants with either significant pH indices or endoscopic changes (Moore 2003). Of those studies in both infants and children, one study included participants with symptomatic GORD (Zohalinezhad 2015), and six studies undertook corroborative investigations (pH/impedance and endoscopy) (Buts 1987; Carroccio 1994; Cucchiara 1984; Cucchiara 1993; Kierkus 2011; Simeone 1997). Of the studies in children aged one year or older, one study included children with symptomatic GORD (Naeimi 2019), and 10 studies undertook corroborative investigations (endoscopy, pH/impedance studies, or both) (Baker 2010; Borrelli 2002; Gilger 2006; Gunesekaran 2003; Haddad 2013; Omari 2006; Tolia 2006; Tolia 2010a; Tolia 2010b; Tsou 2006). Fourteen studies contained suitable summary data for extraction (described below in 'Interventions and comparisons'). Of those 14 studies, two studies had data on both infants and children (Cucchiara 1984; Zohalinezhad 2015); we discuss these in Included studies and Effects of interventions but do not present them in the summary of findings tables.

Interventions and comparisons

Studies in infants

Two studies with summary data assessed proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) versus placebo (Moore 2003 assessed omeprazole, Davidson 2013 assessed esomeprazole); one study with summary data compared a PPI (omeprazole) with another medication (ranitidine) (Azizollahi 2016); and two studies with summary data assessed a PPI given in different doses (Kierkus 2011 assessed pantoprazole, Hussain 2014 assessed rabeprazole). For H₂ antagonists, Azizollahi 2016 compared ranitidine with another medication (omeprazole). There were no studies with summary data that assessed prokinetics or magnesium alginate.

Studies in children

Six studies with summary data assessed a PPI. Two studies compared a PPI with another medication: Pfefferkorn 2006 compared omeprazole to additional ranitidine, and Zohalinezhad 2015 compared omeprazole to quince syrup. Three studies compared different doses of a PPI: Baker 2010 and Tolia 2006 assessed pantoprazole, Haddad 2013 assessed rabeprazole. For H₂ antagonists, as noted above, Azizollahi 2016 compared ranitidine to omeprazole. Two studies assessed quince syrup: as noted above, Zohalinezhad 2015 compared quince syrup to omeprazole, and Naeimi 2019 compared ranitidine plus quince syrup to ranitidine alone.

Outcomes

Studies in infants