Abstract

Background and purpose:

Prostate cancer is the second cause of death among men. Nowadays, treating various cancers with medicinal plants is more common than other therapeutic agents due to their minor side effects. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of taraxasterol on the prostate cancer cell line.

Experimental approach:

The prostate cancer cell line (PC3) was cultured in a nutrient medium. MTT method and trypan blue staining were used to evaluate the viability of cells in the presence of different concentrations of taraxasterol, and IC50 was calculated. Real-time PCR was used to measure the expression of MMP-9, MMP-2, uPA, uPAR, TIMP-2, and TIMP-1 genes. Gelatin zymography was used to determine MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzyme activity levels. Finally, the effect of taraxasterol on cell invasion, migration, and adhesion was investigated.

Findings/Results:

Taraxasterol decreased the survival rate of PC3 cells at IC50 time-dependently (24, 48, and 72 h). Taraxasterol reduced the percentage of PC3 cell adhesion, invasion, and migration by 74, 56, and 76 percent, respectively. Real-time PCR results revealed that uPA, uPAR, MMP-9, and MMP-2 gene expressions decreased in the taraxasterol-treated groups, but TIMP-2 and TIMP-1 gene expressions increased significantly. Also, a significant decrease in the level of MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzymes was observed in the PC3 cell line treated with taraxasterol.

Conclusion and implications:

The present study confirmed the therapeutic role of taraxasterol in preventing prostate cancer cell metastasis in the in-vitro study.

Keywords: MMP-2, MMP-9, PC3 cell, Prostate cancer, Taraxasterol

INTRODUCTION

In advanced communities, cancer is the main cause of death and the second fatal factor in developing countries. According to GLOBOCAN, about 1.41 million new prostate cancer cases were registered in the year 2020 globally (1,2). Prostate cancer is second cause of death in men, and it constitutes a large percentage of diagnosed cancers, which usually occur in men between the ages of 50 and 70 (3,4). Today, the standard treatment for this type of cancer includes surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy (5,6). Paclitaxel is a chemotherapeutic agent for prostate cancer that inhibits cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis by disrupting the function of the Bcl-2 protein (7). Although the use of this drug is beneficial for most patients initially, acquired resistance to chemotherapy is the most critical problem in the successful treatment of these tumors, and over time this tumor shows greater resistance to treatment (8). Vincristine, vinblastine, vindesine, vinorelbine (Vinca alkaloids); paclitaxel, dextaxel (taxanes); etoposide, teniposide (derivatives of the podophyllotoxin) and doxorubicin, daunorubicin, daunorubicin, etc. (anthracyclines) are the most common natural anticancer drugs (9,10).

Herbs often have antioxidant activity, and in addition to pain and inflammation, they are effective against some diseases such as diabetes and cancer, which cause an increase in free radicals and the resulting pain (11,12). Dandelion or Taraxacum officinale is a plant from the Taraxacum genus and the Asteraceae family, which is one of the most well-known and oldest plants used in traditional medicine. Dandelion grows in different regions of the world, including warm and temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, and can withstand drought and frost (13,14). In traditional medicine, plenty of therapeutic benefits of this plant have been mentioned due to its hepatic and hypoglycaemic effects, treatment of blisters, elimination of spleen and liver problems and cancer (15). Taraxasterol is a pentacyclic triterpene with the chemical formula (3β, 18α, 19α)-Urs-20(30)-en-3-ol) and has been isolated from various plants, including dandelion (16). Previous studies have shown that dandelion extract has antiproliferative properties and induces apoptosis in liver cells and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (17,18,19). Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) as a zinc-containing family of proteolytic enzymes, are important factors in angiogenesis, invasion, migration, metastasis, and growth. The various components degrades by MMP in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (20).

The expression of MMP-9 and MMP-2 is associated with increased malignancy and tumor progression, and the activity of these proteases is strongly regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). TIMPs, associated with MMPs, have been described as a predictive factor of survival and might predict the recurrence in cancer (21). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) along with MMPs are the main proteolytic enzymes that destroy ECM and basement membranes. In cancer progression and invasion, the expression of MMP-9, MMP-2, uPA and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptors (uPAR) increases. (21,22,23). Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation are common methods of treating most cancers. Prostate tumors usually do not respond to chemotherapy, and chemotherapy has many side effects. Therefore, efforts to discover new therapies are always ongoing. This study, aimed to investigate the effect of taraxasterol on invasion, migration, adhesion and anti-metastatic role of prostate cancer cell lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and chemicals

Human prostate cancer cell line (PC3; NCBI code: CRL-1435) was purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran. They were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic solution. The cells were stored in an incubator at 37 °C and 90% humidity and 5% carbon dioxide. Once the cells had reached 80% density, trypsin/EDTA solution was used to release the cells from the flask. The active ingredient taraxasterol was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Germany; Cas No. 1059-14-9). To dilute taraxasterol, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used to dissolve the substance and then it was diluted in the culture medium. Gelatin-agarose beads (Cat. No. G-5384, Sigma) were used for the zymography test.

Cell survival assessment

Viability assays were used to show the percentage of living cells in a cell suspension. In this study, we used two methods to evaluate cell viability in different concentrations of taraxasterol. The IC50 values were measured in the micromolar range in the presence of different high and low concentrations of taraxasterol.

Trypan blue staining

The assay was based on the rule that living cells with healthy cell membranes excrete dyes similar to trypan blue, while dead cells do not. In this test, cell suspension (about 106 cells per mL) was mixed in a ratio of 1:1 with trypan blue solution of 0.4% after about 1 to 2 min of absorption or desorption of dye using a Neobar slide and reverse phase light microscope checked. Living cells have clear cytoplasm and dead cells have dark blue cytoplasm. The number of unstained cells divided to the total number of cells indicates the cell viability percentage. Each group (prostate cancer and taraxasterol treatment) was evaluated in three replications.

MTT assessment

This method is based on reducing yellow water-soluble MTT to insoluble crystals of purple dye by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase enzymes. The crystals are dissolved in organic solvents such as DMSO, and the intensity of the dye produced by the spectrophotometer is measured at 570 nm. For this test, 15,000 cells were poured into each of the 96-well plates, and the environment was changed daily to reach a density of 80%. Then, to each of the wells, the medium with the desired concentrations of taraxasterol (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 μM) was added and after 24, 48, and 72 h, 10 μL of MTT solution was added to each of the wells and incubated in dark place for 3 h at 37 °C. Next, 100 μL of DMSO was added. After the crystals were completely dissolved, the absorption of the wells was read at 570 nm by an ELISA reader. For the non-treated group, a row of plate wells without taraxasterol was considered. The cell viability percentage was calculated by the following equation:

Cell viability %Absorbance of test cellsAbsorbance control cells×100

The IC50 values for taraxasterol were computed using Graph Pad Prism version 8 Software. Each group (prostate cancer and taraxasterol treatment) was evaluated in three replications.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

The effect of taraxasterol on expression levels of TIMP-2, TIMP-1, MMP-9, MMP-2, uPAR, uPA genes, and also GAPDH, as a housekeeping gene, were analyzed. Surface cells were removed after 24 h of treatment and cells were collected by trypsinization, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged to pellet the cells. Thermo Fisher Scientific TRIZol reagent was used for the extraction Total RNA (Massachusetts, USA) (24). Complementary DNA was synthesized using the cDNA synthesis kit (Vivantis Technologies, Selangor DE, Malaysia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tube was placed in a thermal cycler for one cycle, and after cDNA synthesis, the expression of the desired genes was assessed semi-quantitatively using real-time PCR (RT-PCR). The sequence of primers was designed using Gene Runner software and is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primers.

| Genes | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Matrix metalloproteinase-2 | Forward: 5’AGAGGGACCTGCAGAGCCAA3’ Reverse: 5’CATTCGAGGCCTGACGGGAC3’ |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | Forward: 5’CGCTCCTACTCTGCCTGCAC3’ Reverse: 5’CATTCGAGGCCTGACGGGAC3’ |

| Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-2 | Forward: 5’AATGCAGATGTAGTGATCAGGG3’ Reverse: 5’ACTCTATATCCTTCTCAGGCCC3’ |

| Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-1 | Forward:5’CAAGATGTATAAAGGGTTCCAAGC3’ Reverse: 5’TCCATCCTGCAGTTTTCCAG3’ |

| Urokinase-type plasminogen activator | Forward: 5’AACTGTGACTGTCTAAATGGAGG3’ Reverse: 5’AAAGTGACCATTCCCCTCATAG3’ |

| Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor | Forward: 5’ACAACGACACCTTCCACTTC3’ Reverse: 5’GGCAGATTTTCAAGCTCCAG3’ |

| GAPDH | Forward: 5’CAATGACCCCTTCATTGACC3’ Reverse: 5’TTCACACCCATGACGAACAT3’ |

RT-PCR

To evaluate the expression of MMP-9 and MMP-2 genes, mRNA was isolated by the standard TRIZOL method. The cells treated with 114.68 ± 3.28 μM concentration of taraxasterol for 24 h and the non-treated cells were evaluated. RNA extraction was performed based on the standard TRIZOL method and the samples were stored at -70 °C. In the following, cDNA was synthesized in 20 μL of the experimental mixture according to the manufacturer's kit (Fermentas, GmbH, Germany). The temperature protocol for 20 μL of the test mixture was 50 min at 65 °C, followed by 60 min at 42 °C and finally 70 °C for 5 min. RT-PCR was performed in a volume of 25 μL of master mix, reverse and forward specific primer (each 12 μL), cDNA (1 μL), and nuclease-free water (10 μl). At first, one cycle at 95 °C for 3 min as general denaturation, then 40 cycles of the below program: denaturation: 20 s at 95 °C, annealing: 45 s at 58, 62, and 63 °C for GAPDH (control gene), MMP-2, and MMP-9 respectively. Elongation was done at 72 °C for 1 and 5 min.

The design and production of specific primers were done by Cinagen Company, Tehran, Iran. Two pairs of primers were designed which are forward: 5`-AACCAGAATCTCACCACCCTC-` 3 and reverse: 5`-AGAAAAACCCCAGGCCTTCA-`3 for MMP2 and forward: 5`-TTCCCGGAGTGAGTTGAACC-3 and reverse: 5-ACTTTCTGGCACGTAGAAAGCA-3 for MMP9 gene.

Scratch assay

The cancer cells treated with taraxasterol were performed by in vitro scratch test due to analysis of migration ability. Prostate cells were cultured in a four-well plate with 70,000 cells per well and allowed to form a monolayer. Then, the monolayers were scraped using a sterile pipette tip and rinsed with PBS. The IC50 concentration (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) of taraxasterol was added to the plates and incubated for 24 h for the next steps. Imaging was then performed using a reverse microscope. Image analysis was performed using TScratch software version 1.0 (Math Works Inc., MA and USA). Each group (prostate cancer and taraxasterol treatment) was evaluated in three replications.

Invasion assay

This test was performed to determine the effect of taraxasterol on the invasion potential of cancer cells using CytoSelect 24 - invasion assay kit (ECM550, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) based on the manufacturer's working method. In summary, the cells pretreated with IC50 concentration (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) of taraxasterol were housed in a serum-free medium for 24 h, while the 10% FBS medium was in the lower chamber. After 6 h of incubation, the cells that crossed the membrane were stained and imaged with a reverse microscope. After extracting the cell dye, the adsorption of each sample was read at 560 nm. Each group (prostate cancer and taraxasterol treatment) was evaluated in three replications.

Adhesion assay

This test was used to determine the effect of taraxasterol on cell adhesion properties. Prostate cancer cells treated with taraxasterol were incubated in a plate of 4 wells with gelatin for 20 min at 37 °C. After 2 h, the cells, treated with taraxasterol at IC50 (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) for 24 h, were suspended in a medium after trypsinization. Five hundred cells were planted in the wells and incubated. Adherent and non-adherent cells immersed in paraformaldehyde were washed with PBS. After staining and dye extraction from the cells, the adsorption of each sample was read at 560 nm. Each group (prostate cancer and taraxasterol treatment) was evaluated in three replications.

Zymography test

MMP-9 and MMP-2 activities were measured using the gelatin zymography method. The medium containing the respective cells was collected and then centrifuged to remove the residues (400 g, 5 min at 4 °C). Then, 40 μL of the clarified supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of 4× sample buffer (1 mL of 25 mM Tris-HCl; 0.8% sodium dodecyl sulfate; 4% glycerol; and 0.001% aqueous bromophenol; pH 6.8. Cell line (PC3) was electrophoresed on 7% polyacrylamide gel with copolymerized gelatin substrate. Then, 24 h later, the gel was placed in an enzyme-activating solution and in a staining solution (10% acetic acid, 5% methanol, and 0.5% coomassie blue R-250, at dH2O) for at least 1 h or until a uniform dark blue gel. Afterward, the gel was fixed with a solution (5% acetic acid, 10% methanol in dH2O) and stained with coomassie brilliant blue to reveal clear bands. Gels were photographed by Gel Doc 2000 gel documentation system (Bio-Rad) and quantitative analysis was performed with densitometry software. Each group (prostate cancer and taraxasterol treatment) was evaluated in two replications.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. The treatment groups were compared to the untreated group using one-way ANOVA. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

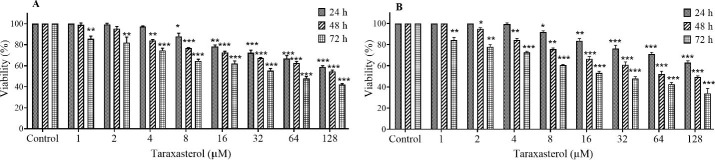

Cell viability

The effect of taraxasterol on proliferation and cell survival was tested using MTT assay and trypan blue staining, after 24, 48, and 72 h. The results showed that taraxasterol reduced the survival rate of PC3 cells, time- and concentration-dependently (Fig. 1). The IC50 values were calculated as follows: 114.68 ± 3.28, 108.70 ± 5.82, and 49.25 ± 3.22 μM for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, by MTT assay and trypan blue staining.

Fig. 1.

Viability percentage of PC3 cells after 24, 48, and 72 h treatment with taraxasterol by (A) MTT and (B) trypan blue assay. The non-treated group received the same volume of serum-free medium and served as the control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant differences in comparison with the control groups.

Effect of taraxasterol on migration, invasion, and adhesion of PC3 cells

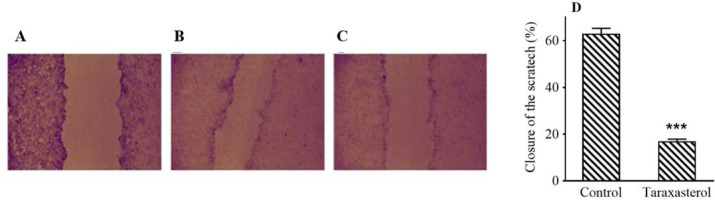

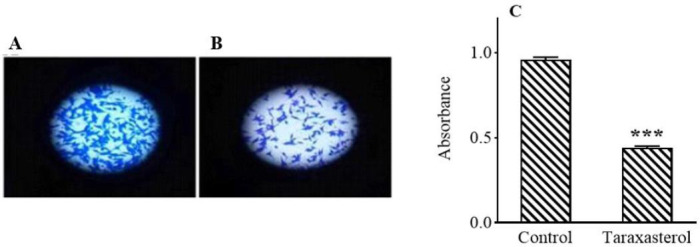

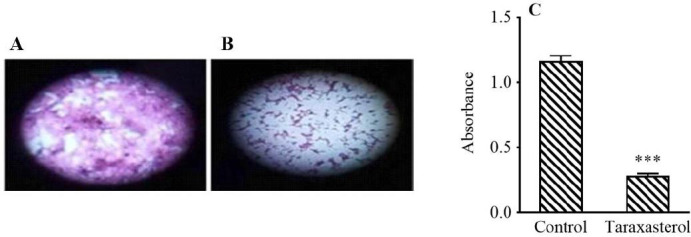

Scratching test results by TScratch software showed that IC50 (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) of taraxasterol for 24 h reduced PC3 cell migration by 75% (Fig. 2). The IC50 of taraxasterol also diminished the potential for cell invasion by 54% (Fig. 3). The results showed that taraxasterol at IC50 reduced cell adhesion up to 76% (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

The effect of taraxasterol on PC3 cell migration ability by scratch assay. (A) The non-treated group in zero-day, (B) non-treated group after 24 h, (C) after treatment with taraxasterol, and (D) mean scratch closure percentage in PC3 cell line. ***P < 0.001 Indicates a significant difference compared to the control group.

Fig. 3.

The effect of taraxasterol on the ability of PC3 cells invention after 24 h. (A) Non-treated group, (B) after treatment with taraxasterol, and (C) bar graph of mean absorbance at 560 nm. ***P < 0.001 Indicates significant difference compared to the control group.

Fig. 4.

The effect of taraxasterol on PC3 cell adhesion ability after 24 h by adhesion assay. (A) Non-treated group, (B) after treatment with taraxasterol, and (C) bar graph of mean light absorbance at 590 nm. ***P < 0.001 Indicates significant difference compared to the control group.

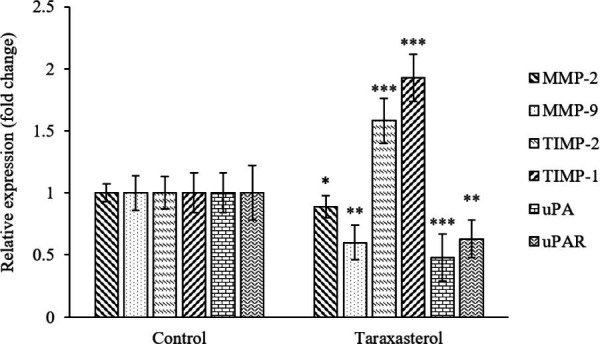

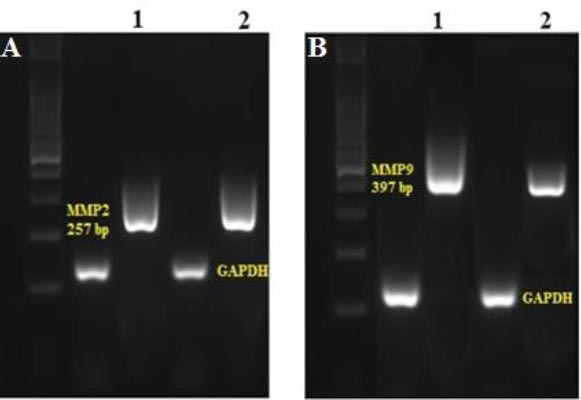

Effect of taraxasterol on the expression of relevant proteolytic genes in PC3 cells

Based on the results of RT-PCR, the expression of uPAR, uPA, MMP-9, and MMP-2 in the taraxasterol-treated group (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) was significantly lower than the non-treated group in the PC3 cells. In addition, the expression of TIMP-2 and TIMP-1 in the taraxasterol-treated group meaningfully increased in comparison with the non-treated group (Fig. 5). The qualitative level of MMP-2 and MMP-9 genes on agarose gel is shown in the group treated with taraxasterol (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) and the non-treated group (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

The effect of taraxasterol on the gene expression levels of proteolytic enzymes in PC3 cells after 24 h was assessed using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Non-treated group was considered the control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant differences in comparison with the respective control groups.

Fig. 6.

The qualitative level of (A) MMP-2 and (B) MMP-9 genes on agarose gel 1.5%. 1, The non-treated group in PC3 cell; 2, the treated group with taraxasterol.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity

According to the results of the zymography test, different MMPs were observed in the supernatant of cell cultures. Besides, the results of the zymography test showed that MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzyme activity in the taraxasterol-treated group (114.68 ± 3.28 μM) decreased compared to the non-treated group (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Gelatinase activity in PC3 cell by gelatinous zymography. (1 and 2) Taraxasterol-treated samples, (3 and 4) non-treated group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the anticancer effects of taraxasterol on cell survival were tested. The results showed that taraxasterol reduced the survival rate of PC3 cells at 114.68 ± 3.28, 108.70 ± 5.82, and 49.25 ± 3.22 μM for 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. Recently, studies on natural anticancer products have increased, and these compounds can be promising treatments because they fight and eliminate cancer cells without affecting healthy cells. (25,26). On the other hand, there is a serious shortage of factors that target the invasion of cancer cells (27). Taraxasterol as a substance in the structure of Taraxacum officinale has been shown to have no cytotoxic effect on normal cells (19,28).

So far, no study has been found on the therapeutic effect of the active ingredient taraxasterol on prostate cancer cell lines. The results of the present study revealed that taraxasterol reduced the migration, invasion, and adhesion potential of PC3 cells. Herbal medicines such as dandelion have anticancer activity in the tumour cell line by inducing apoptosis as well as inhibiting invasion and migration and the adhesion of tumour cells (29,30). In addition, studies have shown that taraxasterol, an essential bioactive compound in dandelion, has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumour activity (19,31).

The results of this study also indicated that the expression of uPAR, uPA, MMP-9, and MMP-2 in the taraxasterol treatment group significantly decreased in the PC3 cell. On the other hand, the expression of TIMP-2 and TIMP-1 increased in the taraxasterol-treated group compared to the non-treated group. It has also been shown that the MMP family, including MMP 9 and MMP 2, are involved in the invasion, development, occurrence, and finally metastasis of tumors through different mechanisms (32,33,34). TIMP-2 and TIMP-1 endogenous inhibitors control the MMP-9 and MMP-2 in cancer cells. Therefore, the decrease in MMP activity is related to the increase in TIMPs activity (35,36). Another important ECM proteinase is uPA, which degrades and breaks down matrix proteins such as fibronectin, collagen IV, and laminin in order to provide the basis for cancer. It also, can activate MMP-9, MMP-3, and MMP-2 and help to grow and expand cancer cells (37,38). Plant-based natural substances detract the expression of MMP-2 MMP-9 in tumour cells (39,40). Recent studies have shown that taraxasterol reduced MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels in thyroid and gastric cancers (41,42).

Our results also confirmed that the activity of MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzymes in PC3 cells treated with taraxasterol significantly decreased in comparison with the non-treated group. According to various studies, the activity level of MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzymes increased in different tissues and cancer cells (43,44). Moreover, it has been emphasized that the activity of MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzymes in smokers and diabetics are considered important risk factors for prostate cancer (45). Decreased activity of MMP-9 and MMP-2 enzymes in tumor cells such as carcinoma of the liver, intestine, stomach, and breast has been confirmed by some factors and substances of plant origin, etc. (43,46,47,48). Therefore, these results endorse the therapeutic role of taraxasterol in preventing the growth of cancer cells.

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study displayed that taraxasterol inhibited the spread of cancer cells by decreasing the expression levels of MMP-9, MMP-2, and MMP enzymes, thereby reducing the invasion, adhesion, and migration potential of PC3 cells. Thus, the results of this study confirms the therapeutic role of taraxasterol in preventing the metastasis of the prostate cancer cell in the in-vitro study.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors confirmed no conflict of interest in this study.

Authors’ contributions

M. Movahed developed the hypothesis and performed the literature search. M. Movahed, M. Pazhouhi, and H. Esmaeili contributed to the design and conceptualization of the experiments described. M. Movahed and M. Pazhouhi analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. B. Jalali Kondori carried out a thorough analysis of the text. All authors has approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The current study was financially supported by Baqiyatullah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, I.R. Iran through Grant No. F2R&P151.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellinger J, Alajati A, Kubatka P, Giordano FA, Ritter M, Costigliola V, et al. Prostate cancer treatment costs increase more rapidly than for any other cancer-how to reverse the trend? EPMA J. 2022;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13167-022-00276-3. DOI: 10.1007/s13167-022-00276-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elmehrath AO, Afifi AM, Al-Husseini MJ, Saad AM, Wilson N, Shohdy KS, et al. Causes of death among patients with metastatic prostate cancer in the US from 2000 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2119568,1–11. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19568. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stranne J, Brasso K, Brennhovd B, Johansson E, Jäderling F, Kouri M, et al. SPCG-15: a prospective randomized study comparing primary radical prostatectomy and primary radiotherapy plus androgen deprivation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer. Scand J Urol. 2018;52(5-6):313–320. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2018.1520295. DOI: 10.1080/21681805.2018.1520295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagshaw HP, Arnow KD, Trickey AW, Leppert JT, Wren SM, Morris AM. Assessment of second primary cancer risk among men receiving primary radiotherapy vs surgery for the treatment of prostate cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2223025,1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.23025. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.23025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukhtar E, Adhami VM, Mukhtar H. Targeting microtubules by natural agents for cancer therapymicrotubule-targeting agents for cancer chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(2):275–284. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0791. DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Q, Dong Y, Zhang Y, Fu H, Chen C, Wang L, et al. Sequential release of pooled siRNAs and paclitaxel by aptamer-functionalized shell-core nanoparticles to overcome paclitaxel resistance of prostate cancer. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(12):13990–4003. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c00852. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.1c00852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaik BB, Katari NK, Jonnalagadda SB. Role of natural products in developing novel anticancer agents: a perspective. Chem Biodivers. 2022;19(11):e202200535,1–13. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202200535. DOI: 10.1002/cbdv.202200535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang D, Kanakkanthara A. Beyond the paclitaxel and vinca alkaloids: next generation of plant-derived microtubule-targeting agents with potential anticancer activity. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(7):1721,1–23. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071721. DOI: 10.3390/cancers12071721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbari B, Baghaei-Yazdi N, Bahmaie M, Mahdavi Abhari F. The role of plant-derived natural antioxidants in reduction of oxidative stress. Biofactors. 2022;48(3):611–633. doi: 10.1002/biof.1831. DOI: 10.1002/biof.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khazaei M, Pazhouhi M. Protective effect of hydroalcoholic extracts of Trifolium pratense L. on pancreatic β cell line (RIN-5F) against cytotoxicty of streptozotocin. Res Pharm Sci. 2018;13(4):324–331. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.235159. DOI: 10.4103/1735-5362.235159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lis B, Olas B. Pro-health activity of dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) and its food products-history and present. J Funct Foods. 2019;59:40–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.05.012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kour J, Sharma R, Nayik GA, Ramaiyan B, Sofi SA, Alam MS, et al. Nayik GA, Gull A. Antioxidants in vegetables and nuts-properties and health benefits. Springer: Singapore; 2020. Dandelion; p. 237. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-15-7470-2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mir MA, Sawhney S, Jassal M. In-vitro antidiabetic studies of various extracts of Taraxacum officinale. Pharma Innov J. 2015;4(1):61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Sang R, Zhao X, Li C, Wang W, Wang M, et al. Research Note: Taraxasterol alleviates aflatoxin B1-induced oxidative stress in chicken primary hepatocytes. Poult Sci. 2023;102(1):102286,1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102286. DOI: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sang R, Yu Y, Ge B, Xu L, Wang Z, Zhang X. Taraxasterol from Taraxacum prevents concanavalin A-induced acute hepatic injury in mice via modulating TLRs/NF-κB and Bax/Bc1-2 signalling pathways. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):3929–3937. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1671433. DOI: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1671433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao T, Ke Y, Wang Y, Wang W, Li Y, Wang Y, et al. Taraxasterol suppresses the growth of human liver cancer by upregulating Hint1 expression. J Mol Med. 2018;96(7):661–672. doi: 10.1007/s00109-018-1652-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00109-018-1652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamal FZ, Lefter R, Mihai CT, Farah H, Ciobica A, Ali A, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of Taraxacum officinale essential oil. Molecules. 2022;27(19):6477,1–18. doi: 10.3390/molecules27196477. DOI: 10.3390/molecules27196477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T, Zhou L, Li D, Andl T, Zhang Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts build and secure the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:60,1–58. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00060. DOI: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azevedo Martins JM, Rabelo-Santos SH, do Amaral Westin MC, Zeferino LC. Tumoral and stromal expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and VEGF-A in cervical cancer patient survival: a competing risk analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):660,1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07150-3. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-020-07150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh SL, Hsieh S, Lai PY, Wang JJ, Li CC, Wu CC. Carnosine suppresses human colorectal cell migration and intravasation by regulating EMT and MMP expression. Am J Chin Med. 2019;47(2):477–494. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X19500241. DOI: 10.1142/S0192415X19500241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajasinghe LD, Pindiprolu RH, Gupta SV. Delta-tocotrienol inhibits non-small-cell lung cancer cell invasion via the inhibition of NF-κB, uPA activator, and MMP-9. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:4301–4314. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S160163. DOI: 10.2147/OTT.S160163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamir-Nasta T, Abbasi A, Kakebaraie S, Ahmadi A, Pazhouhi M, Jalili C. Aflatoxin G1 exposure altered the expression of BDNF and GFAP, histopathological of brain tissue, and oxidative stress factors in male rats. Res Pharm Sci. 2022;17(6):677–685. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.359434. DOI: 10.4103/1735-5362.359434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim C, Kim B. Anti-cancer natural products and their bioactive compounds inducing ER stress-mediated apoptosis: a review. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1021,1–29. doi: 10.3390/nu10081021. DOI: 10.3390/nu10081021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Li H, Zhang J, Zhao C, Lu S, Qiao J, et al. The combinatory effects of natural products and chemotherapy drugs and their mechanisms in breast cancer treatment. Phytochem Rev. 2020;19(5):1179–1197. DOI: 10.1007/s11101-019-09628-w. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy M, McGowan P, Gallagher W. Cancer invasion and metastasis: changing views. J Pathol. 2008;214(3):283–293. doi: 10.1002/path.2282. DOI: 10.1002/path.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Xiong H, Liu L. Effects of taraxasterol on inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141(1):206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menke K, Schwermer M, Felenda J, Beckmann C, Stintzing F, Schramm A, et al. Taraxacum officinale extract shows antitumor effects on pediatric cancer cells and enhance mistletoe therapy. Complement Ther Med. 2018;40:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.03.005. DOI: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Man J, Wu L, Han P, Hao Y, Li J, Gao Z, et al. Revealing the metabolic mechanism of dandelion extract against A549 cells using UPLC-QTOF MS. Biomed Chromatogr. 2022;36(3):e5272. doi: 10.1002/bmc.5272. DOI: 10.1002/bmc.5272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li C, Zheng Z, Xie Y, Zhu N, Bao J, Yu Q, et al. Protective effect of taraxasterol on ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury via inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;89:107169. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107169. DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Z, Wang J, Su Q, Luan M, Chen X, Xu X. The role of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the metastasis and development of hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87(5):521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.10.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan Q, Yuan T, Ding Q. Clinical value of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and-9 in ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation treatment for papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(8):0300060520917581,1–10. doi: 10.1177/0300060520917581. DOI: 10.1177/0300060520917581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammadi F, Javid H, Afshari AR, Mashkani B, Hashemy SI. Substance P accelerates the progression of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via MMP-2, MMP-9, VEGF-A, and VEGFR1 overexpression. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(6):4263–4272. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05532-1. DOI: 10.1007/s11033-020-05532-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Figueira R, Gomes LR, Neto JS, Silva FC, Silva ID, Sogayar MC. Correlation between MMPs and their inhibitors in breast cancer tumor tissue specimens and in cell lines with different metastatic potential. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):20,1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-20. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang ZD, Huang C, Li ZF, Yang J, Li BH, Liang RR, et al. Chrysanthemum indicum ethanolic extract inhibits invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma via regulation of MMP/TIMP balance as therapeutic target. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(2):413–421. DOI: 10.3892/or_00000650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaiswal RK, Varshney AK, Yadava PK. Diversity and functional evolution of the plasminogen activator system. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;98:886–898. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.029. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ismail AA, Shaker BT, Bajou K. The Plasminogen-activator plasmin system in physiological and pathophysiological angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1):337,1–19. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010337. DOI: 10.3390/ijms23010337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Zeng Z, Wang S, Li T, Mastriani E, Li QH, et al. Main components of pomegranate, ellagic acid and luteolin, inhibit metastasis of ovarian cancer by down-regulating MMP2 and MMP9. Cancer Biol Ther. 2017;18(12):990–999. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1394542. DOI: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1394542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bi Q, Wang M, Zhao F, Wang M, Yin X, Ruan J, et al. N-Butanol fraction of Wenxia formula extract inhibits the growth and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer by down-regulating Sp1-mediated MMP2 expression. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:594744,1–10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.594744. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2020.594744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu J, Li X, Zhang S, Liu J, Yao X, Zhao Q, et al. Taraxasterol inhibits TGF-β1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in papillary thyroid cancer cells through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(12_suppl):S87–S95. doi: 10.1177/09603271211023792. DOI: 10.1177/09603271211023792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen W, Li J, Li C, Fan HN, Zhang J, Zhu JS. Network pharmacology-based identification of the antitumor effects of taraxasterol in gastric cancer. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2020;34:2058738420933107,1–6. doi: 10.1177/2058738420933107. DOI: 10.1177/2058738420933107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao L, Niu H, Liu Y, Wang L, Zhang N, Zhang G, et al. LOX inhibition downregulates MMP-2 and MMP-9 in gastric cancer tissues and cells. J Cancer. 2019;10(26):6481–6490. doi: 10.7150/jca.33223. DOI: 10.7150/jca.33223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hingorani DV, Lippert CN, Crisp JL, Savariar EN, Hasselmann JP, Kuo C, et al. Impact of MMP-2 and MMP-9 enzyme activity on wound healing, tumor growth and RACPP cleavage. PloS One. 2018;13(9):e0198464,1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198464. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiani A, Kamankesh M, Vaisi-Raygani A, Moradi MR, Tanhapour M, Rahimi Z, et al. Activities and polymorphisms of MMP-2 and MMP-9, smoking, diabetes and risk of prostate cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(12):9373–9383. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05968-5. DOI: 10.1007/s11033-020-05968-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandlik DS, Mandlik SK. Herbal and natural dietary products: upcoming therapeutic approach for prevention and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73(11-12):2130–2154. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1834591. DOI: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1834591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai CF, Chen JH, Chang CN, Lu DY, Chang PC, Wang SL, et al. Fisetin inhibits cell migration via inducing HO-1 and reducing MMPs expression in breast cancer cell lines. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;120:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.059. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roca-Lema D, Martinez-Iglesias O, de Ana Portela CF, Rodríguez-Blanco A, Valladares-Ayerbes M, Díaz-Díaz A, et al. In vitro anti-proliferative and anti-invasive effect of polysaccharide-rich extracts from Trametes versicolor and Grifola frondosa in colon cancer cells. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16(2):231–240. doi: 10.7150/ijms.28811. DOI: 10.7150/ijms.28811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]