Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine the combined effects and relationships between social media exposure, job insecurity, job stress, and anxiety among individuals and to propose an innovative model exploring how these factors contribute to increased anxiety.

Patients and Methods

This empirical research paper focuses on understanding the role of job insecurity, social media exposure, and job stress in predicting anxiety levels. The study was conducted on a sample of 292 white-collar employees in various organizations and institutions across the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing economic crisis, during the broader transition to a digital working environment. A self-report Likert-type questionnaire was administered to measure employees’ job stress, uncertainty, anxiety levels and social media exposure. The present study employed theoretical background of Lazarus’ Theory of Psychological Stress and the JDR Model. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the relationships between these constructs, while confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity of the measurement model.

Results

The study provides empirical support for the claim that employees with pervasive job stress will likely develop anxiety symptoms. It also highlights the mechanisms by which social media exposure increases employees’ anxiety levels and how management and policymakers can buffer the stressors.

Conclusion

The research emphasizes the importance of addressing occupational mental health problems, and the implications of the findings indicate the need for managerial interventions in securing effective measures for buffering stress and controlled social media usage. This study contributes to the body of knowledge by informing managers and policymakers on key aspects to consider in promoting psychological balance and a healthy organizational climate.

Keywords: anxiety, job stress, social media use, JDR-model, Lazarus theory of stress, psychological wellbeing

Introduction

Recent studies have significantly advanced our understanding of human behavior, including the interplay between job stress, technological advancements, and mental health outcomes.2,6,7,9 Substantial changes in personal and organizational daily functioning following the global health and socio-economic crisis propelled the usage of social media sites for acquiring information, conducting business, and alleviating infrastructural costs for businesses.10 Job insecurity has become a more prominent issue for policymakers, psychologists, and business managers alike.12 The number of persons experiencing insecurity due to the prospect of layoffs and ambiguity characteristic of the transition to a new virtual paradigm is continually growing. Happiness and wellbeing are a principal concern for both individuals and organizations13 (Guberina et al, 2023).14

These factors combined may have adverse effects on mental health outcomes. Job stress among employees is a well-researched area in organizational studies and is a significant topic due to its impact on various mental health outcomes.7,16,17 Job stress has been linked to anxiety,2 depression,18,19 sleep disturbances,20 and increased worry,21 which may, in turn, contribute to physical health issues (Schneiderman et al, 2005).22 Over the last few years, comprehensive scholarly attention has been dedicated to the interplay between social media and mental health, lending support to both positive23 and negative accounts9,24 of organizational and psycho-social outcomes.25,26 An intriguing prospect of leveraging the benefits of personal and business networking platforms for knowledge sharing and corporate communication culminated in the development of social media management studies.27 Within the next few years, mastering technological advancements and AI is likely to become a key competency for many organizations and employees alike.28,29 At the moment it also represents a source of uncertainty about the work and future in general. The overwhelming stress workers are currently faced with due to social media overload is bound to magnify. The central problem of job stress arising due to the exhaustion of resources through excessive social media exposure is an increasingly relevant issue as the majority of enterprises are prevalently embracing remote work and restructuring business models to include a digital work environment. There has been disagreement among scholars concerning the influence and impact of digitization on productiveness, and further empirical evidence is required to understand how this overlap affects mental health.

We undertook this study with a few research questions in mind, namely: Through what specific mechanisms does social media exposure increase employees’ anxiety levels, and how can management and policymakers buffer the stressors? How does the exposure to social media during health and economic crises (like the COVID-19 pandemic) influence job insecurity, job stress, and anxiety? How does job stress mediate the relationship between social media exposure and anxiety?

This study’s main objective is to examine the combined effects and relationships between social media exposure related to COVID pandemic, job stress, job security and anxiety among individuals. Prior studies have primarily focused on these variables individually or as moderators, but not in combination with social media exposure.30–32 While prior studies have explored social media exposure and mental health outcomes during COVID pandemic33,34 none have incorporated job stress and insecurity as key variables of the model. Our study aims to close this gap by proposing a novel model that explores how social media exposure, stress levels, and job insecurity contribute to increased anxiety.

We theorize that individuals perceiving their career prospects as uncertain due to internal or external influences are more prone to anxiety and job stress, which increases with social media exposure. We further contend that such intense insecurity buildup may result in increased job stress. Furthermore, in line with extensive existing studies, we aim to provide additional empirical support for the claim that employees with pervasive job stress will likely develop anxiety symptoms. Our research will allow for a more in-depth understanding of the relationship between these variables and ramifications for occupational health. Moreover, we contribute to the body of knowledge by informing managers and policymakers on key aspects to consider in the development of interventions and policies for promoting psychological balance and a healthy organizational climate.

Given the fact that all-inclusive social media embeddedness in organizational structural business models and everyday operational processes culminated only in the aftermath of major disasters and disruption of regular operational activity (Susanto et al, 2021),35–37 knowledge on occupational stress stemming from the usage of personal and professional social media platforms extending beyond working hours is largely based on limited data (Yue, 2022). In light of recent health and economic crises and major advancements in IT, there is now considerable concern about how further digital transformation and far-reaching technological progression will affect employees’ mental health.

Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

Lazarus’ Theory of Stress

We developed a unique framework for our research model, building upon the theoretical background of prominent Lazarus’ Theory of Stress and Job-Demand-Control Model.

The Lazarus Theory of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1986)38 stipulates how job insecurity and workplace social media exposure act as significant psychological stressors and lead to anxiety. Both uncertainty about the future of continued employment and exhaustion from continuously being at disposal through social media are considered draining for one’s resources and potentially harmful to mental health.39 The Lazarus Theory of Stress postulates that psychological tension arises from the transactional interaction between a person and the environment. Psychological stress occurs when an individual appraises the environment as being strenuous or surpassing their resources, thereby endangering their well-being.40 Fundamental to the theory are concepts of appraisal and coping. Appraisal encompasses an individual’s assessment of how crucial the occurrence in the environment is for their well-being. Coping entails cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific demands.41

Job-Demand-Control Model

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model42 is a well-grounded framework positing that job characteristics of excessive workload and increased demands (such as job insecurity and job stress) can lead to strain, while job resources (such as social support and autonomy) can provide useful strategies for improving self-efficacy and competency, thus reducing stress.43 Social media use can potentially serve as a job resource by providing social support and a sense of community, but it can also be a job demand if it leads to information overload and distraction.

Job insecurity and job stress can be appraised as threatening or challenging, which can lead to anxiety.44 Social media exposure can also be appraised as positive or negative, depending on the individual’s perception of the content and their level of engagement. Overall, these theories suggest that job insecurity, social media exposure, and job stress can all contribute to anxiety levels.

Job Insecurity Impact on Anxiety

Anxiety has been linked to depression, work-family conflict, and other negative outcomes that may result in severe illness45 or adverse actions such as violence and suicide (Hammen, 2005).46 In the organizational context, it arises when employees perceive a lack of resources to meet the prescribed job requirements. Anxiety manifests in multiple forms, ranging from negative thoughts, depletion of energy, irritability, and feelings of hopelessness, to generalized anxiety disorder bordering on panic47 (Leung et al, 202248).49 The Lazarus Theory of Stress is a practical framework for explaining how job uncertainty leads to emotional exhaustion, fear, and anxiety. Job insecurity acts as a significant stressor when employees perceive the environment as being threatening to their well-being.50 When employment is considered uncertain, individuals feel uneasy as they begin to expect their resources for coping with the demands of their work role are insufficient. This leads to a struggle to manage the threat and maladaptive coping, such as excessive worry, depression, and anxiousness.51 Consequently, all these factors contribute to an overarching climate of insecurity. Therefore, we conclude:

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant positive relationship between job insecurity and anxiety levels among individuals.

Social Media Usage, Anxiety, and Job Stress

Several studies have illustrated a positive connection between social media use and anxiety.52 For example, literature points to a multitude of empirical evidence suggesting greater use of social media was associated with higher levels of anxiety and psychological distress53–55 among college students, adolescents,56 and adult working population57 (Lambert et al, 2022).58

During the COVID pandemic and economic fallout from socio-political tensions, social-media disclosed information on crises significantly contributed to increased symptoms of anxiety and stress.59 Given that information from social media does not come from verified sources, technological literacy,60 which includes the competence of critical evaluation and selection of information from social media, is considered to be able to help reduce symptoms of identity and mood disorders. Moreover, social media usage inevitably leads to addiction and information overload,61,62 inciting a combination of the “fear of missing out” and exhaustion due to exposure to a huge amount of data that a person cannot process.63 Considering that confirmation bias is in effect when unconfirmed or dubious messages are received via social platforms from trusted friends and family members, affective reactions may range from slightly intensified worry to extreme anxiety. When misinformation increases risk perception, individuals start panicking.64 Social media can negatively influence employees’ perception of an organization or the certainty of their employment.9,24,51 When damaging perceptions are shaped by social media, exposure becomes a source of strain and uncertainty.65 Misinformation, unverified accounts, and misleading Intel lead to confusion and anxiety.66 Therefore, we conclude:

Hypothesis 2: Social media exposure is positively related to anxiety levels among individuals.

Work stress has previously been found to have detrimental implications for psychological well-being and psychological safety.67 Nigatu and Wang,68 found that job stress and work-related risk lead to stress, anxiety, and lower psychological well-being. Uncertainty heightens emotional arousal and anxiety, thus leading to elevated anticipation of threats (Endler et al, 2001).69 Repetitive worry generates chronic stress proneness characterized by a lack of self-control and the ability to overcome uncontrollable conditions.70 There is an array of academic research providing evidence for the significant relationship between job stress and anxiety disorders.71

Researchers have previously indicated there is a significant positive relationship between work stress and mental impairment.72 According to the research results, job insecurity is significantly positively associated with increased anxiety and depression and negatively affects employees’ perception of their own competence and self-efficacy.68 Employees’ personal resources, such as the ability to multitask, propensity for assuming a proactive approach, self-efficacy, tacit knowledge, and the ability to allocate and successfully coordinate tasks are, when there is stability and security, invested in organizational processes.73,74 In addition, some studies have found that workplace stress and anxiety deplete key resources,75 contribute to reduced subjective and objective well-being, and increase workers’ turnover intention and determination to seek alternative employment.76 Furthermore, previous academic research has tested the link between reduced job satisfaction and mood disorders, especially anxiety and trauma. Work exhaustion and overload,77 accompanied by pronounced fear of failing to meet work task criteria and job loss,75 lead to depersonalization, depression, anxiety, and escalate work stress among employees.78

Hypothesis 3: Job stress is positively related to anxiety levels among individuals.

Propelled by the rapid advancement of IT technology, social media sites, and collaboration platforms, organizations are systematically embedding social networks into their corporate processes.79 The introduction of social media has blurred the boundaries between private and professional life,80 leading to difficulties in the management of different role identities81 or being forced to integrate multiple spheres and enact divergent, and at times opposing, roles in a single situation.82

Moreover, recent crises and the introduction of remote work have led to intensified work-related communication that goes beyond the workplace and regular working hours.83 While this has proved to be of great convenience for employers due to improved flexibility, employees are now faced with extreme anxiety-inducing technostress (Zhang et al, 202084),85 especially with the rise in job demands, required availability, and time pressure. The mixed results on the psychological and organizational outcomes call for further investigation on the topic. For instance, Zheng and Davidson86 found social media to be conducive to increasing organizational commitment and team relatedness, while Liu et al87 produced evidence that work-related social media intensifies work enthusiasm and reduces stressors. Conversely, Tandon et al (2022)88 contend that exposure magnifies the fear of missing out, thus leading to both job exhaustion and burnout. In the same vein,9 assert that prolonged exposure reduces job satisfaction and loosens employees’ organizational commitment. Exhaustive and continuous communication that entails multitasking, including messaging, checking notifications, texting multiple people simultaneously, and receiving diverse tasks from different superiors, has a devastating effect on mental health.51 Such an “always on disposal” scenario significantly increases psychological distress, uncertainty, and uneasiness, resulting in anxiety. Employees’ emerging obligation for constant availability violates the personal-professional boundary,89 impeding on private time, creating both role-identity disturbance (Dodanwala, Santoso and Yukongdi (2022)82 and work-family conflict, which are strenuous for employees.90 Such conflicts lead to intense dissatisfaction and frustration. In accordance with the fundamentals of Lazarus’ Theory of Stress, the appraisal of workplace social media exposure as being distracting, exhausting, and overwhelming has negative side-effects. These include threats to productivity and job security,53 making them incongruent with employees’ personal goals. Therefore, we conclude:

Hypothesis 4: There is a positive relationship between social media exposure and job stress among individuals.

Job Insecurity and Increased Job Stress

Employees experiencing job insecurity are less emotionally invested in organizations due to financial concerns and limited opportunities for career advancements.91 The potential of losing monetary and nonmonetary benefits increases anxiety and reduces organizational commitment. Uncertainty is further propelled by organizational restructuring, failures, and bankruptcies, as these factors intensify the threat perception.92 Such negative appraisal induces work stress and may lead to increased turnover intention.93 Furthermore, job stress is fueled by underlying fear and insecurity concerning the prospect of realizing future career goals,94 increasing autonomy, self-efficacy, and achieving personal growth.71 It encompasses a prominent worry over losing social support, status, performance feedback, and acquisition of additional resources.12,95 The impact of job stress on employee well-being has been widely recognized, and emerging evidence points to a potential link between this stress and the use of social media.96

Psychosocial stress that arises as a consequence of job insecurity leads to a reduction in proactivity and the depletion of employees’ essential resources97 (Sverke et al, 200298). These are, in line with the postulates of Lazarus’s Theory of Stress, expended on the appraisal and development of effective coping strategies. When employees perceive that their current job is threatened and that their future employment opportunities are reduced, they engage in self-doubt, feel anxious, depressed, exhausted, drained, and stressed (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2008).99 Job stress and exhaustion significantly affect job performance, as they lower employees’ job satisfaction and deprive workers of valuable resources, thus diminishing their productivity and effectiveness.

Hypothesis 5: Job insecurity is positively related to job stress among individuals.

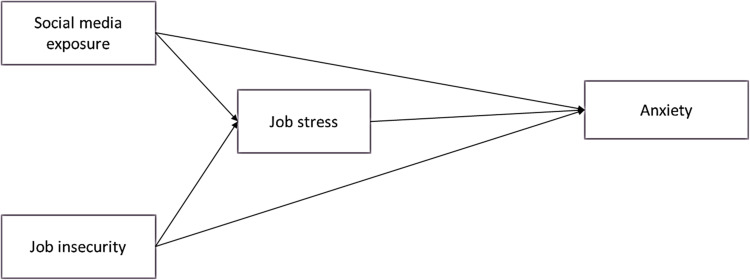

The research model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Methodology

The methodology adheres to a positivist research philosophy as it strives to result in generalizable findings. It is explanatory in nature and employs empirical survey research design. Quantitative methods were executed to evaluate a population of white-collar employees across the United States of America. We implemented a survey strategy involving an online questionnaire, distributed to employees from a range of organizations and institutions, working in information technology, electronics, medicine, and biochemistry fields. Random sampling method was applied. The focus was on white-collar employees in order to maintain a consistent sample for research purposes, and the lack of studies investigating the particular sample within our study context. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Review Board of Zagreb’s School of Economics and Management. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants. Participants were informed on the study’s purpose, anonymity, and their right to withdraw from the survey at any time if needed. The standardized questionnaire was used to collect demographic information, social media exposure, job insecurity, job stress and anxiety data. The items were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale. A total of 500 emails were sent out and 292 fully completed questionnaires were returned. The final sample consisted of 292 participants. The analyzed sample consisted of 52.3% males and 47.7% females, with a majority of respondents (69.2%) being over 50 years old and 26.8% of the respondents were between 30 and 50 years old. Approximately 91.8% of the participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher, while the remaining 9.2% possessing a high school degree. In terms of employment status, 63.4% of the respondents worked 40 hours or more per week, while the rest worked less than 40 hours weekly. The data was further analyzed using multivariate statistics, more precisely Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Measurements

Job Insecurity

The job insecurity (JI) scale, adapted from De Witte (2000),100 measured the extent of JI from two perspectives: one considering the influence of an individual’s external environment on their job insecurity level, and the other combining both cognitive and affective appraisals, ie, the impact of personal perceptions of these situations on their job insecurity level. Four items assessed JI, as follows: “(1) It is likely that I will lose my job soon, (2) I am confident I can maintain my job, (3) I am uncertain about my job’s future, and (4) I believe I may lose my job in the near future”. The scale demonstrated a satisfactory level of reliability (α = 0.82). Response options spanned from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on a 5-point Likert scale.

Social Media Exposure

The social media exposure scale adopted from Ng et al (2018)101 was used to assess social media exposure. Sample items included: “I saw many pictures regarding COVID-19 being shared on my social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc”.; “I saw many posts that relate to health information about COVID-19 that were shared by people in my social network”; and “I saw many people making comments on others’ status updates about COVID-19”. The items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5).

Anxiety

The seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorders (GAD-7) scale is used to measure general anxiety and worry symptoms across various settings and populations. The GAD-7 scale has demonstrated sufficient reliability in previous studies (Tong et al, 2016;102 Wang et al, 2018103). The GAD-7 scale comprises seven items, with each item scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1” representing “not at all” to “5” representing “almost every day”. Sample items include “Becoming easily annoyed or irritable” and “Being so restless that it’s hard to sit still”.

Job Stress

A 5-item scale from Maunder et al (2006)104 was used to assess job stress. Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they encountered these on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Sample items include: “There was an increase in conflict among colleagues at work”, and “I had to work overtime”. Internal consistency of the scale was adequate.

Results

The study utilized structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the relationships between anxiety levels, social media exposure, job insecurity, and job stress. Multivariate statistics were used to capture the complexity of the relationships. The sample size equaled to 292 participants (N = 292). Descriptive statistics for job security, job stress, social media exposure, and anxiety levels were calculated first. The mean for job security score equals to 1.8086, with a standard deviation (SD) being 0.86558 whereas job stress had a mean score of 3.0518 (SD = 1.15513). Social media mean score equaled to 3.2553 (SD = 1.23236) and the anxiety had a mean score of 2.0041 (SD = 1.01624). The descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| N | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job security | 292 | 3.63 | 0.92 | 4.55 | 1.8086 | 0.86558 | 0.749 |

| Job stress | 292 | 4.10 | 1.03 | 5.13 | 3.0518 | 1.15513 | 1.334 |

| Social media | 292 | 3.93 | 0.97 | 4.90 | 3.2553 | 1.23236 | 1.519 |

| Anxiety | 292 | 4.24 | 1.07 | 5.30 | 2.0041 | 1.01624 | 1.033 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 292 |

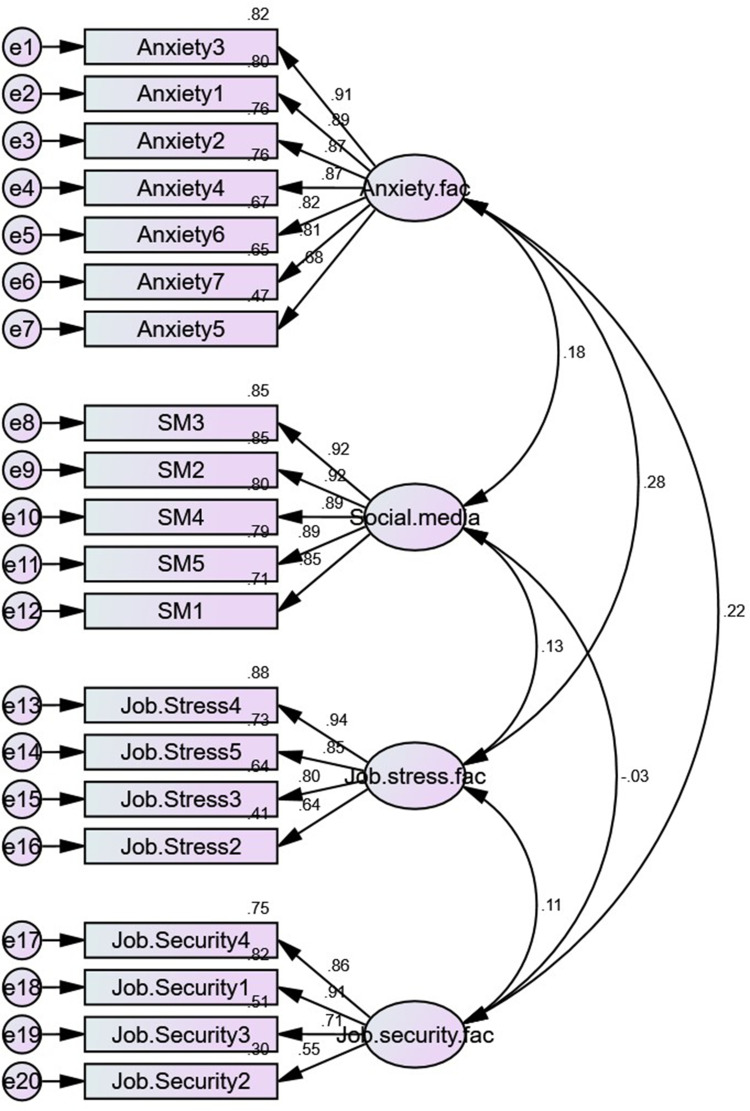

Next, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity of the measurement model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Measurement model.

The composite reliability values were from 0.85 to 0.95. The composite reliability values and average variance extracted values indicate good internal consistency and convergent validity, respectively. The average variance extracted values were from 0.59 to 0.80 whereas the maximum shared variance values ranged from 0.03 to 0.08. The maximum value of the correlation matrix was under the threshold of 0.95, indicating absence of multicollinearity. The indicator values are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model Validity Measures

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | Anxiety | Social Media | Job Stress | Job Security | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0.943 | 0.706 | 0.076 | 0.952 | 0.84 | |||

| Social media | 0.952 | 0.799 | 0.033 | 0.955 | 0.183** | 0.894 | ||

| Job stress | 0.887 | 0.667 | 0.076 | 0.927 | 0.276*** | 0.126* | 0.817 | |

| Job security | 0.85 | 0.594 | 0.047 | 0.9 | 0.216*** | −0.031 | 0.109† | 0.771 |

Notes: ***p < 0.001. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05. †p < 0.10. The diagonal elements (bolded values) are the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct.

Goodness of fit was evaluated next. The model fit measures suggest that the CFA model had an acceptable fit to the data. While the CFI and RMSEA values were slightly below the recommended thresholds, the CMIN/DF and SRMR values indicated an excellent fit. The results are displayed in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Model Fit Measures

| Measure | Estimate | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN | 416.414 | -- | -- |

| DF | 164 | -- | -- |

| CMIN/DF | 2.539 | Between 1 and 3 | Excellent |

| CFI | 0.947 | >0.95 | Acceptable |

| SRMR | 0.076 | <0.08 | Excellent |

| RMSEA | 0.073 | <0.06 | Acceptable |

These findings suggest that the measurement model was valid and that the measures used in the SEM analysis were suitable for capturing the model constructs. We infer that observed relationships were not due to measurement error or any other issues with the measurement model.

Next, the goodness of fit was performed for the structural model indicating that the model has an excellent fit to the data. The model is a good representation of the relationships between the variables. The CMIN/DF value of 0.322, the CFI value of 1.00, SRMR value of 0.014, and RMSEA value of 0.00 all indicated excellent fit. The results are displayed in the Table 4.

Table 4.

Model Fit Measures

| Measure | Estimate | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN | 0.322 | -- |

| DF | 1 | -- |

| CMIN/DF | 0.322 | Between 1 and 3 |

| CFI | 1 | >0.95 |

| SRMR | 0.014 | <0.08 |

| RMSEA | 0 | <0.06 |

The path coefficients were calculated and are displayed in the Table 5. The estimated strength and direction of the relationships between the variables was calculated. The positive weight of 0.164 for Social media suggests that there is a positive relationship between social media exposure and anxiety levels among individuals, whereas the positive weight of 0.281 for Job security suggests that there is a positive relationship between job security and anxiety levels among individuals.

Table 5.

Path Coefficients

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | Collinearity Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Zero-order | Partial | Part | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | 2.049 | 0.240 | 8.547 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Job security | 0.080 | 0.077 | 0.060 | 1.039 | 0.300 | 0.118 | 0.061 | 0.058 | 0.940 | 1.064 |

| Social media | 0.080 | 0.054 | 0.085 | 1.489 | 0.138 | 0.133 | 0.087 | 0.083 | 0.957 | 1.045 |

| Anxiety | 0.298 | 0.067 | 0.262 | 4.455 | 0.000 | 0.293 | 0.254 | 0.250 | 0.906 | 1.103 |

Note: Dependent Variable: Job.stress.

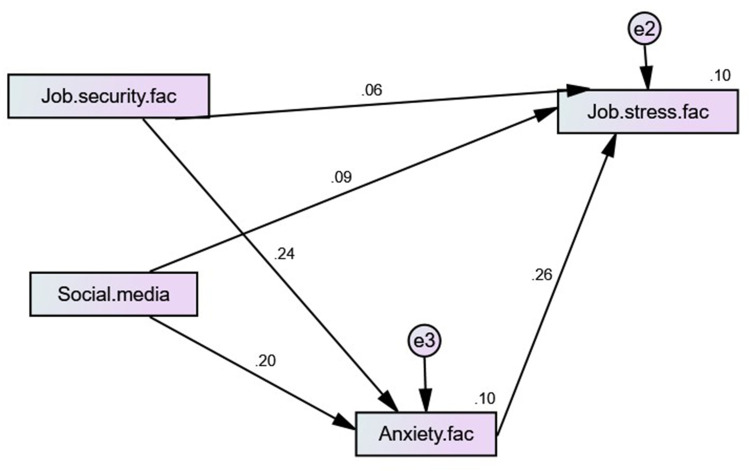

The structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the relationships between four variables: Anxiety, Social media, Job security, and Job stress (Figure 3). The Table 6 presents the following information for each path in the model.

Figure 3.

Structural model testing.

Table 6.

Regression Weights

| Estimate | Std. Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | <--- | Social media | 0.164 | 0.199 | 0.046 | 3.568 | *** |

| Anxiety | <--- | Job security | 0.281 | 0.239 | 0.066 | 4.282 | *** |

| Job stress | <--- | Job security | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.077 | 1.045 | 0.296 |

| Job stress | <--- | Anxiety | 0.298 | 0.263 | 0.067 | 4.478 | *** |

| Job stress | <--- | Social media | 0.08 | 0.085 | 0.053 | 1.498 | 0.134 |

Note: *** (p < 0.001).

The results indicated that social media exposure (S.E. = 0.046, C.R. = 3.568, P < 0.001) and job insecurity (S.E. = 0.066, C.R. = 4.282, P < 0.001) were positively related to anxiety levels among individuals. In addition, job stress was positively related to both anxiety (S.E. = 0.067, C.R. = 4.478, P < 0.001) and job security (S.E. = 0.077, C.R. = 1.045, P = 0.296). However, the relationship between job stress and social media exposure was not statistically significant (S.E. = 0.053, C.R. = 1.498, P = 0.134).

The findings indicated that there is a positive relationship between social media exposure and anxiety levels, as well as between job security and anxiety levels. These results suggest that social media exposure and job security may be important factors to consider when examining anxiety levels in the workplace. Moreover, job stress was found to have a positive relationship with both anxiety levels and job security, highlighting the complex interrelationships between these variables. However, the absence of a significant relationship between job stress and social media exposure indicates that social media exposure may not be a major contributor to job stress among individuals. Overall, these findings emphasize the complexity of the relationships between these variables and suggest that multiple factors should be considered when trying to understand anxiety and stress in the workplace.

Discussion

Natural disasters and pandemics causing economic collapse may widen the gap between rich and poor, with a devastating effect on those with limited access to resources, education, and treatment. Economic stress and the decrease in income are more prevalent for those with weaker employment prospects (Charles & DeCicca, 2008).105 Economic uncertainty brings about the fear of involuntary job loss (Reichert and Tauchmann, 2011), bankruptcy, organizational failure, and narrowing the opportunities to advance one’s career. Stressful situations cause a spiral of negative emotions and attitudes affecting pro-social behaviors; that is, people are less prone to pro-social behavior when they are preoccupied with their family and economic situation.106 The purpose of this study was to discriminate between antecedents of mental health impairment among the working population that arise due to workplace stressors such as job insecurity and to explore the important role of social media-induced work stress on the development of mental disorders.

As uncertainty arises from ambiguous and vague information, apprehension of external socio-economic situations, and psychological adjustment to changing environments, organizational transformations, and restructuring, it creates role ambiguity. Balancing the influx of data, messages, and notifications from numerous social media channels while maintaining a delicate balance between personal and professional life is perceived as a significant source of stress.90 We theorized that job insecurity leads to anxiety, and our hypothesis 1 is accepted. In this, we have corroborated the results of McGovern et al95 and Leung et al (2022).48 and Nemțeanu and Dabija.97 We theorized that social media exacerbates anxiety and acts as an additional cognitive and psychological stressor.66 The constant connectivity and excessive accessibility across multiple platforms, which has significantly increased during recent health and political crises, force employees to always be on duty. Thus, we argued in our Hypothesis 2 that social media exposure leads to anxiety. The relationship turned significant, and thus hypothesis 2 was accepted. The need for workers to be available at all times goes beyond the workplace and working hours. This evidence is in line with prior findings of Wang, Xu and Xie62 and Tandon et al107 and Taboroši et al.9

Increased levels of work exhaustion, especially during crises, lead to occupational stress. The elevated job stress, especially intensified by a large workload and additional work tasks, time pressure, and anxiety significantly reduces job satisfaction, thus magnifying the effects of job burnout.108 In this context, we argue that job stress is significantly positively related to anxiety in individuals. Our results showed a significant and positive association, thus confirming our Hypothesis 3. This lends support to previous evidence generated by Dhiman,71 and Bakker and de Vries.75

The pressure of being available 24/7 and the need to keep checking work-related updates is a psychological stressor depleting employees of key resources.53,96 We theorized that social media usage is positively related to work stress when individuals are required to commit time and energy to devise a strategy for managing the excessive workload and private lives. In line with Tandon et al107 (Tandon et al 202288), we proposed that when social media usage became an integral requirement of the job role, the increased workload and demanding work tasks induce job strain. Following the reasoning of Taborosi et al9 that “fear of missing out” induces stress and thereby increases emotional exhaustion, our hypothesis 4 argued that there is a positive relationship between social media usage and job stress. Although Nam and Kabutey,24 Etesam et al, (2021), Whelan, Islam and Brooks (2020) and Wheal, Islam, and Brooks (2020)109 corroborated the association between social media and significant burnout and psychological strain, as well as information overload, our results turned insignificant. More specifically, we found no statistically relevant correlation between the two, which contradicts the aforementioned findings. However, even though these results differ from some earlier published works, they seem to be consistent with Zheng and Davidson86 and Liu et al.87

Job insecurity is considered to be a stressor consuming mental and affective resources (McEvoy & Mahoney, 2011110).97 From a psychological perspective, if the stress chronically persists, it overly activates the response system and induces anxiety, and maladaptive coping is likely to be assumed.21,51 Recurring distress is associated with increased task demands, new projects, and additional responsibilities, resulting in an influx of work assignments and generating workload. Accordingly, we have theorized that job insecurity leads to work stress. The results for our hypothesis 5 turned insignificant. It can nevertheless be argued that uncertainty has a detrimental impact on mental health by causing insecurities, dissatisfaction, isolation, and identity disturbance. The current study does not support previous research in this area. Although this result was not anticipated, the reason for this is probably that job stress is a multifaceted construct, and not all factors were accounted for. For instance, individual constitution and Big 5 personalities may moderate the relationship. As each individual has a varying uncertainty tolerance threshold, individual constitutional differences may accordingly play a role in increasing or decreasing work stress. As is well known, many other variables not accounted for in the study may have influenced the relationship, including job demands, workload, and personal life stressors. Furthermore, the association might vary based on industry, whereby social media usage may have a greater impact on work stress in industries that are heavily reliant on continuous connectivity.

As stated in the Introduction, our primary objective was to examine the combined outcomes of social media exposure, job insecurity and job stress on anxiety among employees faced with organizational restructuring, increased implementation of work-related social networking and/or economic uncertainty. This empirical study bridges the existing gap in the literature by addressing the interplay in conjunction of constructs such as information overload, stress and job uncertainty and their detrimental effect on mental wellbeing. Returning to the hypothesis of research model development stating a significant positive association between social media exposure and job stress, we concord that the lack of causation underscores the complexity of the relationship. However, the lack of a statistically significant relationship is not surprising given the fact that diverse personality traits and work demands may have a great impact on the uncertainty tolerance levels among employees. This instantiates the development of new perspectives and stresses the need for further research on potential mediating factors. To add to the ongoing research, our result aligns with more recent studies in occupational psychology. We further expand the existing body of knowledge by examining the implications of enduring social media exposure and its effect on job insecurity and role identity threats. It is reasonable to assume that our implications will further induce a constructive dialogue on the impact of excessive social media usage in remote work contexts and the psychological challenges that are posed by digital transformation and transition to digital environments. This study also responds to the scholarly call for additional empirical evidence on digitization’s effects on employees’ organizational productivity and psychological balance. Although the two should be approached from diverse frameworks, it would be interesting to see how the intersection between collective and individual interact during economic hardship. Although certain predictions turned insignificant, our findings add to the analysis of mental health, job stress and social media exposure. The ongoing research benefits from a more holistic understanding of the multifaceted nature of these constructs.

The current study yielded significant valuable insights for the field of occupational psychology on the drivers of workplace anxiety and occupational stressors, such as job insecurity due to the introduction of social media platforms to business processes, and plausible role ambiguity and work-family conflict stemming from it.81 We contributed to the theoretical body of knowledge as our investigation further supports and expands well-established theoretical frameworks of Lazarus’ Theory of Stress and Job Demands-Resources model. By exploring how social media increases anxiety, this research provides new ground to affirm the effect of social comparison in an online environment. Additionally, the observations generated in our research further extended the knowledge on work stress management, providing recommendations on how these tensions can be addressed by organizations to foster a secure and supportive environment. The article contributes to the body of knowledge by shedding light on the dynamic interplay between individual and environmental factors in forming employees’ attitudes and behavior.

Implications and Contributions

Our findings indicate the need for managerial interventions in securing effective measures for buffering stress and controlling social media usage, which would mitigate consequences such as job stress and anxiety. Supportive organizations should maintain effective communication and social media updates on the status of the company, new working modes, changes in work processes, and the introduction of new technology. Such organizations will succeed in alleviating stress and buffering anxiety while promoting job security and organizational commitment.

When individuals are exposed to social media messages regarding job insecurity, this can lead to increased anxiety and stress levels. To mitigate the negative effects of social media exposure, individuals may need to limit their usage or avoid it altogether. Employers have a responsibility to provide their employees with accurate and transparent information about the organization’s status, which can help reduce anxiety and increase job security. Additionally, employers may encourage team activities that promote engagement and social support, which can help to reduce work-related stress and anxiety. By taking these steps, individuals and employers can work together to create a healthier and more productive work environment.

The findings will prove useful for managers who need to become aware that their subordinates’ perceptions of the work environment, intrinsic and extrinsic attitudes toward work, and psychological well-being have implications for job performance. Creating supportive work environments that address job insecurity, manage social media usage, and promote employee well-being can lead to increased job satisfaction, reduced turnover intentions, and improved overall performance. As a result, organizations can benefit from investing in programs and initiatives that prioritize employee mental health, facilitate clear communication, and foster a culture of trust and support. Technology can also be introduced to manage the negative outcomes if they do occur, as it is evident from practice that specific uses of tech can be conducive to positive mental outcomes.111,112

Limitations of the Study

Our study has not included certain factors that could moderate or mediate the relationship between social media exposure, job insecurity, and job stress. For example, personality traits and coping styles may play a role in how individuals perceive and react to job insecurity and social media exposure, which could affect their levels of job stress and anxiety. Similarly, the type of social media use (eg, passive scrolling versus active engagement) and the social support individuals receive through social media could also influence their mental health outcomes. Therefore, future research could address these gaps by examining the role of individual differences, social support, and specific types of social media exposure in the relationship between social media exposure, job insecurity, job stress, and anxiety. By doing so, researchers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that contribute to mental health outcomes in the workplace, which can inform the development of interventions and policies aimed at promoting employee well-being.

Conclusion

We developed a unique explanatory framework for examining the relationship between job insecurity, job stress, and anxiety. By building upon the theoretical background of prominent Lazarus’ Theory of Stress and Job-Demand-Control Model, we examined the effects of social media embeddedness into organizational operational processes. We found a strong link between job insecurity, work stress, and general psychological distress. Individuals who experience job insecurity tend to feel psychologically distressed and are more likely to develop various mood disorders, including burnout, overload, distraction, hopelessness, and a general lack of direction and motivation. Contrary to our initial assumptions, the relationships between social media exposure and job stress, as well as between job insecurity and job stress turned insignificant. Thus, we were unable to confirm the effect that is well-established among organizational psychologists. This may be due to other variables that mediate the relationship. It is paramount to emphasize the importance of addressing occupational mental health problems. This has become an increasingly critical theme of scholarly research during recent health and socio-economic crises. Employers, supervisors, team leaders, healthcare professionals, and policymakers now strive to implement policies to protect psychological well-being. Such programs strategically include providing mentoring, advice, encouragement in obtaining autonomy, and supplying employees with techniques for increasing self-efficacy and improving stress management. This requires mentoring in coping with work demands, mindfulness techniques, and workshops to increase concentration and reduce stress. Additional organizational resources are deployed to protect employees from job burnout. This is of utmost importance when considering that a large number of studies have identified a causal link between burnout and turnover intention.

Funding Statement

1. National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number No.20BZX057).2. 2023 Regular Subjects of Hangzhou Philosophy and Social Science Planning (grant numbers NO.Z23YD032).3. China Federation of Radio and Television Associations “2022 Media Literacy Special Research Project” (grant numbers No.2022ZGL011).

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Review Board of Zagreb’s School of Economics and Management under the approval code 1003. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Blom V, Richter A, Hallsten L, Svedberg P. The associations between job insecurity, depressive symptoms and burnout: the role of performance-based self-esteem. Economic Industrial Democracy. 2018;39(1):48–63. doi: 10.1177/0143831X15609118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Contreras S, Gonzalez JA. Organizational change and work stress, attitudes, and cognitive load utilization: a natural experiment in a university restructuring. Personnel Rev. 2021;50(1):264–284. doi: 10.1108/PR-06-2018-0231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodanwala TC, Santoso DS, Yukongdi V. Examining work role stressors, job satisfaction, job stress, and turnover intention of Sri Lanka’s construction industry. Int J Construction Manage. 2022;1–10. doi: 10.1080/15623599.2022.2080931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etesam F, Akhlaghi M, Vahabi Z, Akbarpour S, Sadeghian MH. Comparative study of occupational burnout and job stress of frontline and non-frontline healthcare workers in hospital wards during COVID-19 pandemic. Iran J Public Health. 2021;50(7):1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Cognitive theories of stress and the issue of circularity. Dynamics Stress. 1986;63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li T, Li Y, Hoque MA, Xia T, Tarkoma S, Hui P. To What Extent We Repeat Ourselves? Discovering Daily Activity Patterns Across Mobile App Usage. IEEE Transactions Mobile Computing. 2022;21(4):1492–1507. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2020.3021987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Shi T, Zhou G, et al. Emotion classification for short texts: an improved multi-label method. Humanities Social Sci Commun. 2023;10(1):306. doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-01816-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichert AR, Tauchmann H. The causal impact of fear of unemployment on psychological health. Ruhr Economic Paper. 2011;266. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taboroši S, Popovi´c J, Poštin J, Rajkovi´c J, Berber N, Nikoli´c M. Impact of Using Social Media Networks on Individual Work-Related Outcomes. Sustainability. 2022;14:20. doi: 10.3390/su14137646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Susanto H, Fang Yie L, Mohiddin F, Rahman Setiawan AA, Haghi PK, Setiana D. Revealing social media phenomenon in time of COVID-19 pandemic for boosting start-up businesses through digital ecosystem. Appl System Innovation. 2021;4(1):6. doi: 10.3390/asi4010006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whelan E, Islam A, Brooks S. Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress-strain-outcome approach. Internet Res. 2020;30:869–887. doi: 10.1108/INTR-03-2019-0112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JM, Lee J, Fitzgerald HN, Oosterhoff B, Sevi B, Shook NJ. Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occupational Environ Med. 2020;62(9):686–691. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Liao Y, Wang W, Han X, Cheng Z, Sun G. Is stress always bad? The role of job stress in producing innovative ideas. Knowledge Manage Res Practice. 2023;1–12. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2023.2219402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guberina T, Wang AM, Obrenovic B An empirical study of entrepreneurial leadership and fear of COVID-19 impact on psychological wellbeing: A mediating effect of job insecurity. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0284766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue CA. Exploring Employees’ After-Hour Work Communication on Public Social Media: antecedents and Outcomes. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2022;41:827. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao W, Liao X, Li Q, Jiang W, Ding W. The relationship between teacher job stress and burnout: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2022;12:6499. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.784243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng L, Zhang P, Lim CY. A Study on the Impact of Work Stress on Work Performance for Newly-Employed Teachers of Colleges and Universities in Western China. J Chine Human Resources Manage. 2022;13(2):53–64. doi: 10.47297/wspchrmWSP2040-800505.20221302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS. The Occupational Depression Inventory: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. J Psychosom Res. 2020;138:110249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Zhang J, Hennessy D, Zhao S, Ji H. Psychological strains, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical and non-medical staff in urban China. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YK, Kramer A, Pak S. Job insecurity and subjective sleep quality: the role of spillover and gender. Stress and Health. 2021;37(1):72–92. doi: 10.1002/smi.2974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad SNA, Rasid SZA, Abdul MS, Rasool NAMI. Work Stress and its Impact on Employees’ Psychological Strain. Soc Sci. 2021;11(8):1466–1471. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:607–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noor NSFBM, Shahrom M. The effect of social media usage on employee job performance. Romanian J Information Technol Automatic Control. 2021;31(1):65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam T, Kabutey R. How Does Social Media Use Influence the Relationship Between Emotional Labor and Burnout? The Case of Public Employees in Ghana. J Glob Inf Manag. 2021;29:32–52. doi: 10.4018/JGIM.20210701.oa2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang LV, Liu PL. Ties that work: investigating the relationships among coworker connections, work-related Facebook utility, online social capital, and employee outcomes. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;72:512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Zhu MY, Zhang ZP. How Newcomers’ Work-Related Use of Enterprise Social Media Affects Their Thriving at WorkThe Swift Guanxi Perspective. Sustainability. 2019;11:20. doi: 10.3390/su11102794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mujanah S. Job Accomplishment Through Information Technology Competencies And Corporate Social Media Usage Of Company Employees In Indonesia. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Kewirausahaan. 2022;24(2):159–169. doi: 10.9744/jmk.24.2.159-169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cetindamar D, Kitto K, Wu M, Zhang Y, Abedin B, Knight S. Explicating AI literacy of employees at digital workplaces. IEEE Trans Eng Manage. 2022;1–14. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2021.3138503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarrahi MH, Kenyon S, Brown A, Donahue C, Wicher C. Artificial intelligence: a strategy to harness its power through organizational learning. J Business Strategy. 2022;3:456. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanuša J, Barzut V, Knežević J. Intolerance of uncertainty and fear of COVID-19 moderating role in relationship between job insecurity and work-related distress in the Republic of Serbia. Front Psychol. 2021;12:647972. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Näswall K, Sverke M, Hellgren J. The moderating role of personality characteristics on the relationship between job insecurity and strain. Work Stress. 2005;19(1):37–49. doi: 10.1080/02678370500057850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richter A, Näswall K, Bernhard-Oettel C, Sverke M. Job insecurity and well-being: the moderating role of job dependence. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2014;23(6):816–829. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.805881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmer T, Mepham K, Stadtfeld C. Students under lockdown: comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0236337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Susanto H, Fang Yie L, Mohiddin F, Rahman Setiawan AA, Haghi PK, Setiana D Revealing social media phenomenon in time of COVID-19 pandemic for boosting start-up businesses through digital ecosystem. Appl Sys Innovat. 2021;4(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamal MM. The triple-edged sword of COVID-19: understanding the use of digital technologies and the impact of productive, disruptive, and destructive nature of the pandemic. Information Systems Management. 2020;37(4):310–317. doi: 10.1080/10580530.2020.1820634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naeem M. Using social networking applications to facilitate change implementation processes: insights from organizational change stakeholders. Business Process Manage J. 2020;26(7):1979–1998. doi: 10.1108/BPMJ-07-2019-0310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer publishing company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenyi TE, John LB. Job resources, job demands, uncertain working environment and employee work engagement in banking industry: prevailing evidence of South Sudan. Int J Res Business Soc Sci. 2020;9(2):202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godinic D, Obrenovic B, Khudaykulov A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int J Innovation Economic Dev. 2020;6(1):61–74. doi: 10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015.61.2005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biggs A, Brough P, Drummond S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. Handbook Stress Health. 2017;349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands‐resources model: state of the art. J Managerial Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahmud MS, Talukder MU, Rahman SM. Does ‘Fear of COVID-19’trigger future career anxiety? An empirical investigation considering depression from COVID-19 as a mediator. Int J Social Psychiatry. 2021;67(1):35–45. doi: 10.1177/0020764020935488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khudaykulov A, Changjun Z, Obrenovic B, Godinic D, Alsharif HZH, Jakhongirov I. The fear of COVID-19 and job insecurity impact on depression and anxiety: an empirical study in China in the COVID-19 pandemic aftermath. Curr Psychol. 2022;1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02883-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammen C Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Q, Miao Y, Zeng X, Tarimo CS, Wu C, Wu J. Prevalence and factors for anxiety during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic among the teachers in China. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leung P, Li SH, Graham BM The relationship between repetitive negative thinking, sleep disturbance, and subjective fatigue in women with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(3):666–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rose M, Devine J. Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2022:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguiar-Quintana T, Nguyen THH, Araujo-Cabrera Y, Sanabria-Díaz JM. Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. Int J Hospitality Manage. 2021;94:102868. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen XY, Wei SB. Enterprise social media use and overload: a curvilinear relationship. J Inf Technol. 2019;34:22–38. doi: 10.1177/0268396218802728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heffner J, Vives ML, FeldmanHall O. Anxiety, gender, and social media consumption predict COVID-19 emotional distress. Humanities Social Sci Commun. 2021;8(1). doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00816-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao XF, Yu LL. Exploring the influence of excessive social media use at work: a three-dimension usage perspective. Int J Inf Manag. 2019;46:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.11.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Y, Liu YJ, Zhang JZ, et al. Dark side of enterprise social media usage: a literature review from the conflict-based perspective. Int J Inf Manag. 2021;61:102393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu S, Pitafi AH, Pitafi S, Ren M. Investigating the Consequences of the Socio-Instrumental Use of Enterprise Social Media on Employee Work Efficiency: a Work-Stress Environment. Front Psychol. 2021;12:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2020;25(1):79–93. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, et al. Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(4):323–331. doi: 10.1002/da.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambert J, Barnstable G, Minter E, Cooper J, McEwan D Taking a one-week break from social media improves well-being, depression, and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2022;25(5):287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong FHC, Liu T, Leung DKY, et al. Consuming information related to COVID-19 on social media among older adults and its association with anxiety, social trust in information, and COVID-safe behaviors: cross-sectional telephone survey. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e26570. doi: 10.2196/26570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pekkala K, van Zoonen W. Work-related social media use: the mediating role of social media communication self-efficacy. Eur Manage J. 2022;40(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2021.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu C, Ma J. Social media addiction and burnout: the mediating roles of envy and social media use anxiety. In: Key Topics in Technology and Behavior. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2022:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, Xu J, Xie T. Social Media Overload and Anxiety Among University Students During the COVID-19 Omicron Wave Lockdown: a Cross-Sectional Study in Shanghai, China. Int j Public Health. 2023;67:1605363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teng L, Liu D, Luo J. Explicating user negative behavior toward social media: an exploratory examination based on stressor–strain–outcome model. Cognition Technol Work. 2022;1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malaeb D, Salameh P, Barbar S, et al. Problematic social media use and mental health (depression, anxiety, and insomnia) among Lebanese adults: any mediating effect of stress? Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(2):539–549. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gu X, Obrenovic B, Fu W. Empirical Study on Social Media Exposure and Fear as Drivers of Anxiety and Depression during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2023;15(6):5312. doi: 10.3390/su15065312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. Less sense of control, more anxiety, and addictive social media use: cohort trends in German university freshmen between 2019 and 2021. Curr Res Behav Sci. 2023;4:100088. doi: 10.1016/j.crbeha.2022.100088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Obrenovic B, Jianguo D, Khudaykulov A, Khan MAS. Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: a job performance model. Front Psychol. 2020;11:475. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nigatu YT, Wang J. The combined effects of job demand and control, effort-reward imbalance and work-family conflicts on the risk of major depressive episode: a 4-year longitudinal study. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(1):6–11. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Endler NS, Kocovski NL State and trait anxiety revisited. J Anxiety Disord. 2001;15(3):231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Casale S, Flett GL. Interpersonally-based fears during the COVID-19 pandemic: reflections on the fear of missing out and the fear of not mattering constructs. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17(2):88. doi: 10.36131/CN20200211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dhiman A. Unique nature of appraisal politics as a work stress: test of stress–strain model from appraisee’s perspective. Personnel Rev. 2021;50(1):64–89. doi: 10.1108/PR-05-2019-0276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mensah A. Job stress and mental well-being among working men and women in Europe: the mediating role of social support. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2494. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ho HC, Chan YC. Flourishing in the workplace: a one-year prospective study on the effects of perceived organizational support and psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):922. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources. Model Int j Stress Manage. 2007;14(2):121. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bakker AB, de Vries JD. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: new explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress. 2021;34(1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Modaresnezhad M, Andrews MC, Mesmer‐Magnus J, Viswesvaran C, Deshpande S. Anxiety, job satisfaction, supervisor support and turnover intentions of mid‐career nurses: a structural equation model analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):931–942. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bowling NA, Kirkendall C. Workload: a review of causes, consequences, and potential interventions. Contemporary Occupational Health Psychol. 2012;2:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elsafty A, Shafik L. The impact of job stress on employee’s performance at one of private banks in Egypt during COVID-19 pandemic. Int Business Res. 2022;15(2):24–39. doi: 10.5539/ibr.v15n2p24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Zoonen W, Banghart S. Talking engagement into being: a three-wave panel study linking boundary management preferences, work communication on social media, and employee engagement. J Computer Mediated Commun. 2018;23(5):278–293. doi: 10.1093/jcmc/zmy014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Y, Huang Q, Davison RM, Yang F. Role stressors, job satisfaction, and employee creativity: the cross-level moderating role of social media use within teams. Information Manage. 2021;58(3):103317. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2020.103317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.French KA, Allen TD, Kidwell KE. When does work-family conflict occur? J Vocat Behav. 2022;136:103727. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Zoonen W, Rice RE. Paradoxical implications of personal social media use for work. N Technol Employment. 2017;32(3):228–246. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oksanen A, Oksa R, Savela N, Mantere E, Savolainen I, Kaakinen M. COVID-19 crisis and digital stressors at work: a longitudinal study on the Finnish working population. Comput Human Behav. 2021;122:106853. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang C, Ye M, Fu Y, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teenagers in China. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(6):747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Singh P, Bala H, Dey BL, Filieri R. Enforced remote working: the impact of digital platform-induced stress and remote working experience on technology exhaustion and subjective wellbeing. J Bus Res. 2022;151:269–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zheng BW, Davison RM. Hybrid Social Media Use and Guanxi Types: how Do Employees Use Social Media in the Chinese Workplace? Inf Manag. 2022;59:15. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2022.103643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu D, Hou B, Liu Y, Liu P. Falling in Love with Work: the Effect of Enterprise Social Media on Thriving at Work. Front Psychol. 2021;12:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tandon A, Dhir A, Talwar S, Kaur P, Mäntymäki M Social media induced fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing: Behavioural, relational and psychological outcomes. Technol Forecast Soc. 2022;174:121149. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Afshari L, Young S, Gibson P, Karimi L. Organizational commitment: exploring the role of identity. Personnel Rev. 2020;49(3):774–790. doi: 10.1108/PR-04-2019-0148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oostervink N, Agterberg M, Huysman M. Knowledge Sharing on Enterprise Social Media: practices to Cope With Institutional Complexity. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2016;21:156–176. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hogan NL, Lambert EG, Jenkins M, Wambold S. The impact of occupational stressors on correctional staff organizational commitment: a preliminary study. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2006;22(1):44–62. doi: 10.1177/1043986205285084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bordia P, Hobman E, Jones E, Gallois C, Callan VJ. Uncertainty during organizational change: types, consequences, and management strategies. J Bus Psychol. 2004;18:507–532. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBU.0000028449.99127.f7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Staufenbiel T, König CJ. A model for the effects of job insecurity on performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010;83(1):101–117. doi: 10.1348/096317908X401912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bahadirli S, Sagaltici E. Burnout, job satisfaction, and psychological symptoms among emergency physicians during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Practitioner. 2021;83(25.1):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 95.McGovern HT, De Foe A, Biddell H, et al. Learned uncertainty: the free energy principle in anxiety. Front Psychol. 2022;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yu L, Cao X, Liu Z, Wang J. Excessive social media use at work: exploring the effects of social media overload on job performance. Information Technol People. 2018;31(6):1091–1112. doi: 10.1108/ITP-10-2016-0237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nemțeanu MS, Dabija DC. Negative impact of telework, job insecurity, and work–life conflict on employee behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4182. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sverke M, Hellgren J, Näswall K No security: a meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(3):242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Morgeson FP, Humphrey SE (2008). Job and team design: Toward a more integrative conceptualization of work design. In Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 39–91). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- 100.De Witte H (2000). Arbeidsethos en jobonzekerheid: meting en gevolgen voor welzijn, tevredenheid en inzet op het werk. In Van groep naar gemeenschap. liber amicorum prof. dr. leo lagrou (pp. 325–350). Garant. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ng YJ, Yang ZJ, Vishwanath A To fear or not to fear? Applying the social amplification of risk framework on two environmental health risks in Singapore. J Risk Res. 2018;21(12):1487–1501. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120:31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang HJ, Tan G, Deng Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of depression and anxiety among patients with convulsive epilepsy in rural West China. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;138(6):541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. (2006). Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis, 12(12), [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Charles KK, DeCicca P Local labor market fluctuations and health: is there a connection and for whom?. J Health Econ. 2008;27(6):1532–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Carnevale JB, Hatak I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: implications for human resource management. J Bus Res. 2020;116(2020):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tandon A, Dhir A, Islam N, Talwar S, Mäntymäki M. Psychological and behavioral outcomes of social media-induced fear of missing out at the workplace. J Bus Res. 2021;136:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.07.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Alimoradi Z, Griffiths MD. Impact of COVID‑19‑Related Fear and Anxiety on Job Attributes: a Systematic Review. Asian J Social Health Behav. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Whelan E, Najmul Islam AKM, Brooks S Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach. Internet Res. 2020;30(3):869–887. [Google Scholar]

- 110.McEvoy PM, Mahoney AE Achieving certainty about the structure of intolerance of uncertainty in a treatment-seeking sample with anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(1):112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xiong Z, Liu Q, Huang X. The influence of digital educational games on preschool Children’s creative thinking. Comput Educ. 2022;189:104578. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xiong Z, Weng X, Wei Y. SandplayAR: evaluation of psychometric game for people with generalized anxiety disorder. Arts Psychotherapy. 2022;80:101934. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2022.101934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]