Abstract

Mental disorders in India form a major public health concern and the efforts to tackle these dates back to four decades, by way of the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and its operational arm, the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP). Although the progress of NMHP (and DMHP) was relatively slower till recently, the last 4-5 years have seen rapid strides with several initiatives, including (i) expansion of DMHPs to 90 per cent of the total districts of the country, (ii) the National Mental Health Policy and (iii) strengthening the Mental Health Legislation by way of providing explicit provisions for rights of persons with mental illnesses. Among others, factors responsible for this accelerated growth include the easily accessible digital technology as well as judicial activism. Federal and State cooperation is another notable feature of this expansion. In this review, the authors summarize the available information on the evolution of implementation and research aspects related to India’s NMHP over the years and provide a case for the positive turn of events witnessed in the recent years. However, the authors caution that these are still baby steps and much more remains to be done.

Keywords: District Mental Health Programme, India, National Mental Health Programme, primary mental healthcare

Introduction

One in seven Indians is affected by mental disorders at any given point in time, which amounts to about 200 million people1. This figure contributed to the sixth major cause of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) in the world in 2017 and the second leading cause for contributing to the disease burden in terms of the number of years lived with disability (YCDs)1. Finally, the treatment gap for mental disorders is more than 60 per cent, an alarmingly high proportion with more than half of those affected unable to access appropriate services2. In recent times, however, in India commensurate with the development worldwide, mental health is being given primacy and has also been included in the Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDGs)1. India’s efforts to tackle this huge public health problem date back to the early 1980s, with the launch of the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP). India was among the first countries in South-East Asia3 to have a dedicated mental health programme. It aimed to take mental healthcare to the masses and resonated with the global call of health for all by the year 2000. Its operational arm, the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP), emerging out of the Bellari model, was implemented as a centrally sponsored programme since 19964. Beginning with 27 districts, a decade of expansion resulted in the country having 127 districts under DMHP during the 10th Five-Year Plan. However, an accelerated expansion has occurred over the last five years: currently, the DMHP is functioning in more than 655 of the 724 districts of India. During the same timeframe, numerous other developments have seen the light of the day. Furthermore, research relevant to the area has seen a steady expansion driving progressive policies; some of which seem to have been translated into operational aspects of the programme too.

This study was aimed to trace the trajectory of growth, discusses the continuing challenges and examines whether the tide is really turning for the mental health programme in the Indian subcontinent.

Methodology

A PubMed database and Google Scholar search was conducted up to September 30, 2020 using the terms ‘National Mental Health Program’, ‘District Mental Health Program’, ‘Public Mental Health’, ‘Public Psychiatry’, ‘Population Psychiatry’, ‘Community Psychiatry’, ‘Mental Health Program’, ‘Primary Care Psychiatry’ and ‘India’.

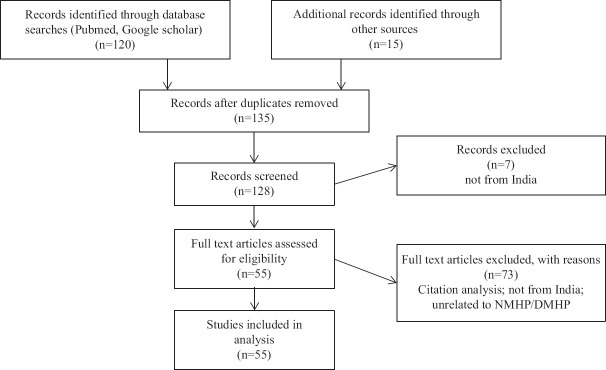

The search strategy used was [National Mental Health Program*(Title/Abstract)] OR [District Mental Health Program*(Title/Abstract)] OR [Public mental health*(Title/Abstract)] OR [Public psychiatry*(Title/Abstract)] OR [Population psychiatry*(Title/Abstract)] OR [Community psychiatry*(Title/Abstract)] OR [Mental health program*(Title/Abstract)] OR [Primary care psychiatry*(Title/Abstract)] AND [India*(Title/Abstract)]. Total hits obtained were 120, out of which 41 studies were included for synthesis. In addition, 12 more articles were included as they were thought to be relevant to the theme of this article. The details are provided in Figure.

Figure.

Flowchart of the study.

Results

Results were divided into the following two parts: (i) tracking the progress and expansion of NMHP (and DMHP); and (ii) the research initiatives. The first part was further subdivided into three distinctive time frames, reflecting the different phases of progression and expansion of NMHP. The first phase was between 1982 and 1996 (inception of NMHP till the beginning of DMHP). The second phase was between 1997 and 2015 (steady expansion of NMHP and DMHP activities). The third phase was between 2016 till date, where several relatively fast developments (and expansion of NMHP/DMHP activities) have occurred. When compared to the expansion of operational aspects, the core research initiatives were found to have progressed steadily throughout, and hence, these were considered a single entity and have been summarized after the operational aspects.

Conceptualization, initiation and initial progress of the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) (1982-1996): Although the NMHP took birth (in 1982) following the Alma Ata declaration in 1978 and the subsequent acceptance of the National Health Policy, the movement of community psychiatry in India started way back in the 1950s, with the experiments in Amritsar Mental Hospital (involving family members in caring for the mentally ill outside the premises of the hospital)3 . Later on, during the 1960s and 70s, models of community care were developed in Ballabhgarh, Raipur Rani and Sakalawara3,5-9 . The latter two went on to form future operational aspects of NMHP. Basically, these experiments established the feasibility of integrating mental healthcare with the general healthcare, by demonstrating that commonly prevalent psychiatric illnesses can in fact be identified and treated by non-specialist medical officers10-17.

However, initial progress was poor, with no tangible improvements and numerous downsides, such as a lack of budgetary estimates, a lack of clarity about who should support the programme (Centre or State), and ambitious short-term goals taking precedence over pragmatic long-term planning. Finally, there were no administrative structures needed to implement NMHP18,19.

As a method of overcoming the above shortcomings (and with the view to scale up), the district was thought to be a better administrative and implementation unit of the mental health programme4. A pilot for this model was started and successfully completed in Bellari district of Karnataka [conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru] based again on the foundations of learnings from Raipur Rani and Sakalawara experience (vide supra), but with one major difference. In this DMHP model, the medical officers of the district would get mentoring, support and monitoring by a mental health team at the district level. The sole purpose of this team is to cover the mental health of the entire district. Thus, the DMHP took birth in 1996 in 27 districts. Initial budget was ₹ 280 million18.

Birth of District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) and progress of NMHP (1997-2016): During the period 1996 to 2016, three important developments occurred: (i) after it began, DMHP saw a steady expansion to a greater number of districts spanning the length and breadth of the country, under the erstwhile five-year plans; (ii) evaluations of the impact of DMHP; and (iii) broadening the scope of NMHP by inclusion of additional objectives.

For example, the budgetary allocation for DMHP rose to ₹ 1390 million under the 10th five-year plan (2002-2007) while its extension covered 110 districts. Another notable thing that happened during this time was the re-vitalization of the NMHP during the 11th five-year plan (2007-2012), wherein additional objectives were added by widening the scope of the programme. For example, specific provisions for (i) 10 acute care beds at the district hospital; (ii) list of essential drugs was broadened to include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, benzodiazepines and injection haloperidol at district hospitals; (iii) programmes such as school mental health was introduced; and finally (vi) the manpower development scheme was introduced. This scheme consisted of two provisions, one namely the establishment of ‘centres of excellence’ in mental health (Scheme-A of the NMHP). Under Scheme-B, government medical colleges/government general hospitals/State-run mental health institutes would also be supported for starting postgraduate courses or to increase intake capacity for mental health PG courses18,20.

Another important development during the period was the successive evaluations of the impact of DMHP. Four such evaluations did occur conducted by both the Governmental (NIMHANS, Bengaluru in 2003) and the Mental Health Policy Groups, constituted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, in 2012 and external agency (Indian Council of Marketing Research in 2008-2009)21. The general observations were that at the district level it was partially successful (but not at primary healthcare level) by way of providing basic care and building better awareness of mental illness. Criticisms included inadequate leadership at the Central and State levels,inaccessibility to funds and several other administrative issues22 .

Additionally this period also saw increased budget allocation for DMHP and NMHP activities (about 10 million per district per annum) and the formulation of the National Mental Health Policy in 2014. However, the coverage of DMHP remained relatively low until the end of 2015.

Has the tide really turned? (2015-to date): The relatively slow expansion of the DMHP and thereby the NMHP has been a matter of intense debate. While the Erwadi tragedy brought to the fore the helplessness of persons with mental illness, it did not succeed in pushing the agenda for mental healthcare in a uniform or dramatic manner23 . The DMHP itself has also received criticism from both academia and policymakers24-26. Such criticisms notwithstanding, the DMHP has presently covered most of the districts in India. As of June 2018, the DMHP was operational in 655 of the 724 districts of the country with a fast expanding coverage. Furthermore, the assessment of quality and best practices under DMHP are underway. Some of these are summarized as follows:

Judicial activism and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC): The judicial activism in the country dates back to more than three decades and has continued to pay rich dividends with regard to mental health in India. The NHRC monitored mental hospitals across the country and came up with recommendations to improve the country’s mental health scenario. The most recent among these is the report by the technical committee of the NHRC giving the following recommendations: at least two psychiatrists need to be deputed at the district level for the DMHP along with other mental health professionals including psychologists, social workers and nurses22 . NHRC has given recommendations for the taluk-level hospitals as well as for the primary healthcare centres. The Supreme Court of India, based on these recommendations, has given directions to both the State governments as well as the union government to take necessary actions22 .

The National Mental Health Policy of India: The first-ever policy dedicated to mental health was released in 2014. Its vision was to promote mental health, prevent and enable recovery from mental illnesses27 . Critically, the missing links in the system were with respect to: (i) care provision for the entire range of mental illnesses, (ii) management of crisis and inpatient services, (iii) continued care in the community, (vi) homeless mentally ill and (v) disability certification. In addition, systemic issues plaguing programme implementation included (i) issues related to the enthusiasm of healthcare staff, (ii) lack of involvement of caregivers, (iii) poor participation of the non-governmental organizations and private sector and (iv) very low intra- and inter-sectoral co-ordination25. These criticisms overrode the islands of positive reports of DMHP implementation (WHO/WONCA report on the Thiruvananthapuram district of Kerala (2008), the Tamil Nadu story of having the maximum number of districts with functional DMHPs and also having a dedicated nodal officer for the DMHP of the State28. The independent evaluation of DMHP by the Indian Council for Market Research, pertinently recommended expansion of this programme to districts across the country. There are good outcomes wherever the DMHP has been effectively implemented. The slow progress and the numerous systemic and administrative issues which eclipse the achievements was noted’. The NHRC report observed that DMHP did ensure a wide access to essential psychotropic medications and that DMHP was accepted as a feasible, relative low-cost, and high-yield public health intervention as shown in States such as Kerala and Gujarat29 .

The Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017: The MHCA 2017 provides for mental healthcare and services for persons with mental illnesses to protect, promote and fulfil the rights of such persons during delivery of mental healthcare and services and for connected matters30.

Proactiveness of the governments: Many States including Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Assam, Meghalaya, Sikkim and Uttarakhand have been approaching centres of excellence in psychiatry (including NIMHANS, Bengaluru, and the Lokamanya Gopinath Bordoloi Institute of Psychiatry, Tezpur, Assam) with requests to mentor and hand-hold its non-specialist doctors and other non-specialist mental health professionals, so that they could start providing mental health services. In addition, the Union Government has also increased the outlay for the NMHP. Schemes A and B for manpower development have also contributed to words this cause. Finally, the number of centres of excellence has shot up significantly to 25 such centres. Such initiatives are expected to have a positive impact on strengthening the DMHP’s reach in providing mental healthcare in the community.

Task force for primary mental healthcare: Recently, the Government of India had set up a task force for primary mental health care, to come up with recommendations for its effective delivery. This is intended for the Health and Wellness centres across the country. Meetings were held at NIMHANS and the curriculum for primary mental healthcare and the methods of delivery were deliberated upon and finalized with the aim to have a positive impact on the accessibility and affordability of primary mental healthcare for the community.

Other factors: The funding to DMHP has been streamlined to a considerable extent. Now, the funds are disbursed through the National Health Mission, which has better methods of fund management31.

There have been considerable positive changes indicating a change in the tide as far as mental healthcare in the country is concerned. A few examples are:

(i) Human resource development schemes under the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP)20: A grant-in-aid of up to ₹ 337 million are available under Scheme A. Under Scheme B, financial support of ₹ 10.67 to 12.5.6 million per department has been provided. Till date, 25 centres of excellence have been started, 88 departments of psychiatry in medical colleges have been upgraded and 29 mental hospitals have been modernized (data taken from the Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, updated till June 2018).

(ii) The Karnataka narrative: The developments in Karnataka’s DMHP are notable as it has moved beyond the Bellary model in all aspects including clinical services (evidenced by the increase in the footfalls to clinics), capacity building and research activities with several innovations and this has potential positive influence other States as well4. Other significant highlights include extending specialised mental healthcare to the taluk/block level and, in some cases, to community health centres and primary healthcare centres, the Manochaitanya Programme, and embracing innovative technologies for meaningful capacity building (Karnataka Tele-mentoring and Monitoring Programme)35,36.

(iii) National level initiatives from the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS): NIMHANS has initiated many efforts over the past few years that could play a critical role in scaling up DMHP across the country. There have been various the mentoring and capacity-building efforts carried out by NIMHANS in collaboration with numerous States. The various types of blended training courses are the way to go forward because they will not place a burden on States’ limited human resources, and the additional mental health training will not be viewed as burdensome as they are based on (a) adult learning principles, and (b) higher translational quotients. However, the authors acknowledge that extensive studies of these training programmes are required before their validity can be confirmed. These assessments are currently being carried out.

(iv) NIMHANS digital academy: This academy offers digital/online fundamental courses on various mental health-related topics to doctors, psychologists, social workers, and nurses. The certified professionals can work for the DMHP (nimhansdigitalacademy.ac.in). As on September 30, 2020, 578 medical officers, 211 psychologists, 120 social workers, and 147 nurses have received diplomas in Community Mental Health. Following the NDA, two other prominent mental health institutes in the country, namely: (a) the Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi32, and (b) Lokamanya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health, Tezpur33, have established comparable digital academies with similar aims.

Research initiatives relevant to the NMHP/DMHP: Research activities related to NMHP and DMHP can be divided into three categories. The first category demonstrates the feasibility of involving non-specialist medical officers in identifying and treating commonly prevalent psychiatric disorders (demonstrating integration of primary mental healthcare into the general healthcare)34 . These concepts have been incorporated into the core operational aspects of NMHP/DMHP as mentioned earlier. The next set of research focused on specific disorders and populations (for example, the elderly, persons with schizophrenia or depression, etc.)35-43. These have potentially informed newer inclusions into the NMHP (guidelines for implementing district-level activities under the 12th five-year plan period). An off-shoot of this is the Taluk Mental Health Programme44 . However, these have seen the light of the day only in a small geographical area of the country. The next big challenge of NMHP is therefore to scale up these initiatives throughout the country. The following paragraph summarizes these initiatives:

With regard to severe mental illnesses, the community-based approaches (community-based interventions) have been shown to be effective in not only symptomatic control but also in limiting disability, meaningfully improving work functioning (even long term) and lastly demonstrating that available resources can be effectively utilized for rehabilitation programmes35-43 . Research has also shown a significant reduction of out-of-pocket expenses if patients use these community resources instead of tertiary care centres45, etc. Since 2020, the following initiatives are underway: systematic assessment to examine the extent of reduction of treatment gap by these community interventions including DMHP, impact of care at doorsteps from the DMHP machinery, to evaluate the impact of technology-based mentoring programme for DMHP staff of a rural DMHP district, evaluation of the impact of Tele-On Consultation Training, validation of the Clinical Schedules for Primary Care Psychiatry and the impact of such community intervention programmes on the number/cost of hospitalizations of persons with schizophrenia, etc.

The other category of research includes a wide variety of disparate dimensions including: Understanding the prevalence of psychiatric disorders46, Increasing the awareness and scaling up services for public mental health care farther than district level47-55, changing perception of healthcare workers56, evaluating indicators for mental healthcare and its success57-61, cross-country situation analysis on maternal mental health and available services62,63 innovations at community level64 and providing evidence to strengthen mental health systems65 .

Future directions

Mentoring and monitoring is one area where technology can be harnessed to the full extent. A couple of initiatives in this direction have already started in Karnataka. Once piloted there, those can be easily expanded throughout the country. (i) The e-monitoring software for mental health now is capable of data entry till the taluk-hospital level and this can easily be extended to the PHCs as well, (ii) Karnataka is also coming up with a comprehensive software management solution for mental healthcare, aligning itself to the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. The mentoring part is already discussed in detail above.

Conclusion

The recent developments in the mental healthcare scenario in India carry potential for improving care across the country. Although, preliminary, the recent developments can be considered promising as the number of patients now having access to the programme appears substantial. With the increasing use of the internet and mobile technology and sustained efforts and support from the policymakers, administrators and academia, an increase in human resources is possible soon. Considering the vast population of India, the wide prevalence of psychiatric disorders and a big treatment gap that still prevails, these numbers, though minuscule, indicate positive beginnings in the right direction.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Sagar R, Dandona R, Gururaj G, Dhaliwal RS, Singh A, et al. India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Mental Disorders Collaborators. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–61. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murthy RS. National mental health survey of India 2015-2016. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:21–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_102_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wig NN, Murthy SR. The birth of national mental health program for India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:315–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parthasarathy R, Channaveerachari N, Manjunatha N, Sadh K, Kalaivanan RC, Gowda GS, et al. Mental health care in Karnataka: Moving beyond the Bellary model of District Mental Health Program. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021;63:212–4. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_345_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murthy RS. National mental health programme in India (1982-1989) mid-point appraisal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1989;31:267–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khandelwal SK, Jhingan HP, Ramesh S, Gupta RK, Srivastava VK. India mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2004;16:126–41. doi: 10.1080/09540260310001635177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thara R, Rameshkumar S, Mohan CG. Publications on community psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S274–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chadda RK. Six decades of community psychiatry in India. Int Psychiatry. 2012;9:45–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das A. The context of formulation of India's Mental Health Program: Implications for global mental health. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;7:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wig NN, Murthy RS, Harding TW. A model for rural psychiatric services-raipur rani experience. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:275–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suman C, Baldev S, Murthy RS, Wig NN. Helping the chronic schizophrenic and their families in the community-initial observations. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:97–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasa Murthy R, Kala R, Wig NN. Mentally ill in a rural community: Some initial experiences in case identification and management. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;20:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrashekar CR, Isaac MK, Kapur RL, Sarathy RP. Management of priority mental disorders in the community. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:174–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaac MK, Kapur RL, Chandrashekar CR, Kapur M, Pathasarathy R. Mental health delivery through rural primary care-development and evaluation of a training programme. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:131–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parthasarathy R, Chandrashekar CR, Isaac MK, Prema TP. A profile of the follow up of the rural mentally ill. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:139–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapur RL. The role of traditional healers in mental health care in rural India. Soc Sci Med Med Anthropol. 1979;13 B:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(79)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murthy RS, Wig NN. The WHO collaborative study on strategies for extending mental health care, IV: A training approach to enhancing the availability of mental health manpower in a developing country. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:1486–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.11.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta S, Sagar R. National mental health programme-optimism and caution: A narrative review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40:509–16. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_191_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murthy RS. Mental health initiatives in India (1947-2010) Natl Med J India. 2011;24:98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha SK, Kaur J. National mental health programme: Manpower development scheme of eleventh five-year plan. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:261–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indian Council for Market Research. Ministry of Health &Family welfare, Government of India. Evaluation of District Mental Health Programme: Final report. 2008. [accessed on October 5, 2020]. Available from: https://mhpolicy.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/evaluation-of-dmhp- icmr-report-for-the-ministry-of-hfw.pdf .

- 22.Murthy P, Isaac MK. Five-year plans and once-in-a-decade interventions: Need to move from filling gaps to bridging chasms in mental health care in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:253–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.192010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trivedi JK. Implication of erwadi tragedy on mental health care system in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:293–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frands AP. Social work in mental health: Contexts and theories for practice. India: SAGE Publications; 2014. p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob KS. Repackaging mental health programs in low- and middle-income countries. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:195–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain S, Jadhav S. Pills that swallow policy: Clinical ethnography of a community mental health program in northern India. Transcult Psychiatry. 2009;46:60–85. doi: 10.1177/1363461509102287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Health &Family Welfare. Government of India. National Mental Health Policy of India. 2014. [accessed on October 5, 2020]. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/National_Health_Mental_Policy.pdf .

- 28.Sarin A, Jain S. The 300 Ramayanas and the district mental health programme. Econ Polit Wkly. 2013;XLVIII:77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Human Rights Commission India. Annual report 2015-2016. [accessed on May 21, 2023]. Available from:www.nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/NHRC_AR_EN_2015-2016_0.pdf .

- 30.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Mental Healthcare Act. 2017. [accessed on June 6, 2019]. Available from: https://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental/Health/Mental/Health care/Act,2017.pdf .

- 31.Directorate General of Health Services. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Goverment of India. National Mental Health Programme. [accessed on July 15, 2021]. Available from:https://dghs.gov.in/content/1350_3_NationalMentalHealthProgramme.aspx .

- 32.Cip Digital Academy. Learning “Best Practices”anywhere, anyone, anytime. [accessed on October 4, 2020]. Available from:http://cipdigitalacademy.in/

- 33.Mental health Education &E-Training (MEET) LGB Regional Institute of Mental Health. Tezpur (Assam) - Digital Academy. Gain, share &digitalize learning. [accessed on October 4, 2020]. Available from: https://www.meetlgbrimh.in/

- 34.Narayana M, Kumar CN, Math SB, Thirthalli J. Designing and implementing an innovative digitally driven primary care psychiatry program in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:109–13. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_214_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatterjee S, Patel V, Chatterjee A, Weiss HA. Evaluation of a community-based rehabilitation model for chronic schizophrenia in rural India. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:57–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatterjee S, Chowdhary N, Pednekar S, Cohen A, Andrew G, Araya R, et al. Integrating evidence-based treatments for common mental disorders in routine primary care: Feasibility and acceptability of the MANAS intervention in Goa, India. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:39–46. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatterjee S, Leese M, Koschorke M, McCrone P, Naik S, John S, et al. Collaborative community based care for people and their families living with schizophrenia in India: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee S, Naik S, John S, Dabholkar H, Balaji M, Koschorke M, et al. Effectiveness of a community-based intervention for people with schizophrenia and their caregivers in India (COPSI): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1385–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62629-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar CN, Thirthalli J, Suresha KK, Venkatesh BK, Arunachala U, Gangadhar BN. Antipsychotic treatment, psychoeducation ®ular follow up as a public health strategy for schizophrenia: Results from a prospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:34–41. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_838_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suresh KK, Kumar CN, Thirthalli J, Bijjal S, Venkatesh BK, Arunachala U, et al. Work functioning of schizophrenia patients in a rural south Indian community: Status at 4-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1865–71. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thirthalli J, Venkatesh BK, Kishorekumar KV, Arunachala U, Venkatasubramanian G, Subbakrishna DK, et al. Prospective comparison of course of disability in antipsychotic-treated and untreated schizophrenia patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:209–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thirthalli J, Venkatesh BK, Naveen MN, Venkatasubramanian G, Arunachala U, Kishore Kumar KV, et al. Do antipsychotics limit disability in schizophrenia?A naturalistic comparative study in the community. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:37–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravilla S, Muliyala KP, Channaveerachari NK, Suresha KK, Udupi A, Thirthalli J. Income generation programs and real-world functioning of persons with schizophrenia: Experience from the Thirthahalli Cohort. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:482–5. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_151_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Chander KR, Sadh K, Gowda GS, Vinay B, et al. Taluk Mental Health Program: The new kid on the block? Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:635–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_343_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sivakumar T, James JW, Basavarajappa C, Parthasarathy R, Naveen Kumar C, Thirthalli J. Impact of community-based rehabilitation for mental illness on 'out of pocket'expenditure in rural South India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;44:138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaji KS, Raju D, Sathesh V, Krishnakumar P, Punnoose VP, Kiran PS, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in the community: A population based-study from Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:149–56. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_162_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haldar P, Sagar R, Malhotra S, Kant S. Burden of psychiatric morbidity among attendees of a secondary level hospital in Northern India: Implications for integration of mental health care at subdistrict level. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:176–82. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_324_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nayak S, Mohapatra MK, Panda B. Prevalence of and factors contributing to anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders among urban elderly in Odisha –A study through the health systems'Lens. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;80:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel V, Goel DS, Desai R. Scaling up services for mental and neurological disorders in low-resource settings. Int Health. 2009;1:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen A, Eaton J, Radtke B, George C, Manuel BV, De Silva M, et al. Three models of community mental health services in low-income countries. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet. 2016;388:3074–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tharayil HM, Thomas A, Balan BV, Shaji KS. Mental health care of older people: Can the district mental health program of India make a difference?Indian J Psychol Med . 2013;35:332–4. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Padmanathan P, Singh M, Mannarath SC, Omar M, Raja S. A rapid appraisal of access to and utilisation of psychotropic medicines in Bihar, India. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts T, Shiode S, Grundy C, Patel V, Shidhaye R, Rathod SD. Distance to health services and treatment-seeking for depressive symptoms in rural India: A repeated cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e92. doi: 10.1017/S204579601900088X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathias K, Jacob KS, Shukla A. “We sold the buffalo to pay for a brain scan”–A qualitative study of rural experiences with private mental healthcare providers in Uttar Pradesh, India. Indian J Med Ethics. 2019;4((NS)):282–7. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2019.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naik AN, Isaac MK, Parthasarathy R, Karur BV. The perception and experience of health personnel about the integration of mental health in general health services. Indian J Psychiatry. 1994;36:18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raja S, Boyce WF, Ramani S, Underhill C. Success indicators for integrating mental health interventions with community-based rehabilitation projects. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008;31:284–92. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283013b0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahuja S, Khan A, Goulding L, Bansal RK, Shidhaye R, Thornicroft G, et al. Evaluation of a new set of indicators for mental health care implemented in Madhya Pradesh, India: A mixed methods study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:7. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-0341-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chadda RK, Sood M, Kumar N. Experiences of a sensitization program on common mental disorders for primary care physicians using problem-based learning approach. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:289–91. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chander R, Basavaraju V, Rahul P, Sadh K, Harihara S, Manjunatha N, et al. A report on a series of workshops on “mental health leadership”for Maharashtra state. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;47:101859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Silva MJ, Rathod SD, Hanlon C, Breuer E, Chisholm D, Fekadu A, et al. Evaluation of district mental healthcare plans: The PRIME consortium methodology. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208((Suppl 56)):s63–l70. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baron EC, Hanlon C, Mall S, Honikman S, Breuer E, Kathree T, et al. Maternal mental health in primary care in five low- and middle-income countries: A situational analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:53. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ng C, Chauhan AP, Chavan BS, Ramasubramanian C, Singh AR, Sagar R, et al. Integrating mental health into public health: The community mental health development project in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:215–20. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.140615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maulik PK, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, Praveen D, Jha V, Patel A. Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment (SMART) Mental Health Programme for providing innovative mental health care in rural communities in India. Glob Ment Health (Camb) 2015;2:e13. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ayuso-Mateos JL, Miret M, Lopez-Garcia P, Alem A, Chisholm D, Gureje O, et al. Effective methods for knowledge transfer to strengthen mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries. BJPsych Open. 2019;5:e72. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]