Abstract

Background

Our increasingly diverse population demands the adoption of transcultural approaches to health care delivery. Training courses in medical education have been developed across the country for cultural competency, but have not been standardized or incorporated consistently. This study sought to formulate an educational intervention in medical training using the concepts of cultural competency and humility to improve understanding of cultural disparities in health care.

Methods

This study used three domains of Tools for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) by the Association of American Medical Colleges. Participants included 106 fourth-year medical students and 19 internal medicine residents at Louisiana State University in Shreveport in 2022. The training session included a lecture introducing cultural and structural competency for 30 minutes followed by three workshops based on the TACCT domains of key aspects of cultural competence, understanding the impact of stereotyping on medical decision-making, and cross-cultural clinical skills. The participants were given a pre- and postsession questionnaire.

Results

After the session, 68% of students rated their understanding of cultural competency as excellent. For methods of teaching—lecture versus workshop versus both—66% rated the combination as excellent.

Conclusion

The rudimentary understanding of cultural competency and cultural humility improved after the session.

Keywords: Cultural competency, cultural humility, health care disparities

Increasing diversity brings opportunities along with challenges for health care providers. The 2002 Institute of Medicine report highlighted issues of medical inequities based on minority status. The report concluded that “bias, stereotyping, prejudice and clinical uncertainty from health care providers contribute to racial and ethnic disparities.”1

Cultural competence has been defined as a development process that enables health professionals to work efficaciously across racial, ethnic, and linguistically diverse populations.2 It emphasizes the requirement of being aware of, and responsive to, patients’ cultural background and perspectives. Cultural humility further includes change in our perspective of cultural diversity.3 As the population becomes increasingly diverse, more attention to linguistic and cultural barriers is needed. It is expected that by 2050, racial and ethnic minorities will comprise 35% of the population >65 years, which means that health services can no longer be tailored to cater to the needs of a culturally homogenous population.4

Although many distinct types of training courses have been developed across the country, these efforts have not been standardized or incorporated into training for health professionals in any consistent manner.5 Cultural competence is a self-reflective practice that can be inculcated, trained, and achieved. We believe that health care training should cultivate humanistic attributes to address and challenge health care disparities, ensuring graduation of culturally sensitive physicians advocating for the health care needs of clinically diverse populations.

This study sought to formulate a semiformal educational intervention for medical students using the concepts of cultural competency and humility to improve understanding of cultural disparities in health care.

Methods

This study used three of the six domains of the Tools for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).6 Participants included three cohorts of fourth-year medical students and internal medicine residents (PGY-1, -2, and -3) at Louisiana State University in Shreveport, Louisiana. The educational intervention was a mandatory addition to the fourth-year medical students’ curriculum and internal medicine residency didactics session.

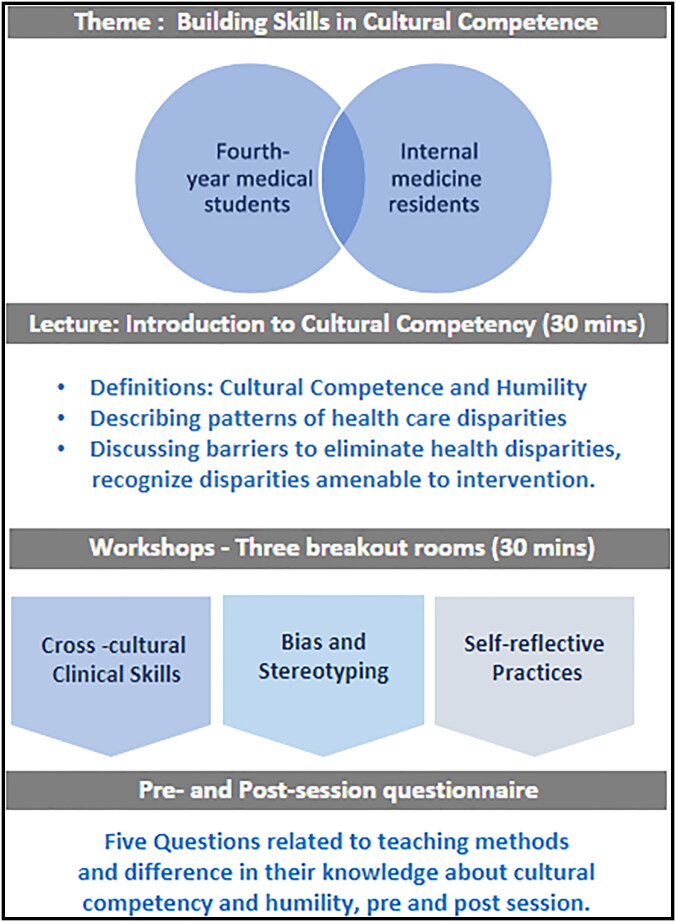

The workshop coordinators included internal medicine attendings and residents, and each coordinator underwent a pretraining session that comprised three modulator training sessions, 1 hour each, by a senior faculty member. A total of 106 fourth-year medical students and 19 internal medicine residents underwent the training, including the lecture followed by breakout rooms for workshops. The theme of the training was building skills in cultural competence; the training session included a 30-minute lecture introducing cultural and structural competency, patterns of health care disparities, and barriers to recognizing and eliminating disparities followed by three breakout sessions (Figure 1). Each cohort attended both the lecture and one of the three workshops through random allocation. The participants were given Post-It labels with the number 1, 2, or 3 as they entered the session; these labels were later used to assign the participants to a workshop. Workshops were based on three TACCT domains: key aspects of cultural competence, understanding the impact of stereotyping on medical decision-making, and cross-cultural clinical skills. Each workshop was moderated by two facilitators, a medicine resident supervised by an internal medicine faculty member. The workshop was designed to include a case that was a hypothetical scenario formulated on the basis of the TAACT domains, followed by an extensive interactive discussion. The 30-minute workshop was broken down into a case review (5 minutes), questions and discussion (15 minutes), and debrief, including take-home points (10 minutes).

Figure 1.

Cultural competency training intervention, including a lecture followed by one of three breakout sessions.

The participants were given a pre- and postsession questionnaire about their opinions about the training, where they rated each question from 1 to 5 (1, poor; 2, fair; 3, good; 4, very good; 5, excellent). The questionnaire asked about understanding of the term cultural competency, understanding of the term cultural humility, and ratings of the lecture alone, workshop alone, and lecture plus workshop. Participant responses were documented and stored in a secure Excel sheet. The data were evaluated through descriptive analysis.

Results

Among the 106 medical students, 58% were men, 79.3% were Caucasian, and the mean age was 26 years (Table 1). After the session, 68% of students rated their understanding of cultural competency as excellent, and 52% rated their understanding of cultural humility as excellent. In addition, 38% rated the lecture alone as good, 37% ranked the workshop alone as very good, and 66% rated the combination as excellent (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variable | Medical students | Medicine residents |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 106 | 19 |

| Gender (%): Male/Female | 58%/42% | 67%/33% |

| Mean age (years) | 26 | 32 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 79.3% | 25.2% |

| African American | 5.1% | 12.2% |

| Asian | 12.8% | 62.3% |

| Hispanic | 2.8% | 0.3% |

| Educational level | Undergraduate | Graduate |

Table 2.

Participant responses for presession and postsession questionnairea

| Questions | Presession questionnaire |

Postsession questionnaire |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical students |

Medicine residents |

Medical students |

Medicine residents |

|

| Understanding of the term cultural competency | 50% (good) |

52% (good) |

68% (excellent) |

57% (excellent) |

| Understanding of the term cultural humility | 50% (good) |

42% (good) |

52% (excellent) | 42% (excellent) |

| Evaluation of the teaching method | ||||

| Lecture alone | 45% (good) |

42% (good) |

38% (good) |

52% (good) |

| Workshop alone | 42% (good) |

43% (good) |

37% (good) |

42% (good) |

| Combination of lecture and workshop | 47% (excellent) |

57% (excellent) |

66% (excellent) |

57% (excellent) |

aResults per the maximum chosen response (out of 1, poor; 2, fair; 3, good; 4, very good; 5, excellent).

Participants also included 19 internal medicine residents, of whom 67% were men, 25.2% were Caucasian, and the mean age was 32 years (Table 1). Of the residents, 57% thought their understanding of cultural competency was very good after the session, and 42% rated their understanding of cultural humility as excellent. In terms of teaching methods, 52% rated the lecture alone as good, 42% rated the workshop alone as good, and 57% residents thought both together were excellent (Table 2).

Discussion

Training in cultural competency is a self-reflective practice. The assessment commences with oneself, awareness of one’s own biases, which further enhances the competency to understand other cultures. Implicit bias is referred to as attitudes or stereotypes affecting understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious way.7 These biases develop over time, primarily influenced by our background and experiences. They continue to form barriers to equity and create disparities in health outcomes. In a 2002 Institute of Medicine report, racial and ethnic minority patients were found to receive lower quality health care than Whites, even when confounding factors were removed, including insurance states and ability to pay for medical expenses. A reflective practice study in 2016 found that physicians were unaware of how their communication patterns varied with respect to ethnic and racial characteristics of the patient.8

The US Office of Minority Health set national standards in 2001 for culturally and linguistically appropriate health care services, primarily being “effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs.”9 Minorities continue to have lower rates of screening and disease awareness, which results in reduced rates of disease awareness and treatment in comparison to the non-Hispanic White population.10 A study with 10,403 participants found an increased risk of undiagnosed medical conditions among minorities.11 Higher rates of health care-associated infections in hospitalized Asian and Hispanic patients were found in a case-control analysis involving 79,019 patients.12 Another study with 322 African American patients in an outpatient setting in four clinics in Detroit, Michigan, found that physicians’ cultural competency as reported by patients was higher in visits with a patient-physician race concordance.13

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education in 2017 suggested that the medical curriculum should include strategies for addressing health care disparities; however, the accreditation bodies do not have a standard approach for implementation.14 Prior independent efforts have been made to improve cultural competency in medical students. A Canadian study using videos about care of the Chinese population showed that 67.3% of students learned useful strategies to better serve immigrant populations.15 International electives and student exchange between the United Kingdom and Japan led to deeper understanding of different health care systems.16 A meta-analysis done on 154 studies on cultural competency in medical education found that most interventions used lectures (54%), followed by discussions (37%), cultural immersion/encounter (27%), and clinical experience (22%).17 In our study, 66% of medical students reported that the combination of lecture and workshop was an excellent approach.

A synergistic combination of cultural competence and humility is known as cultural competemility.18 We inculcated both cultural competence and humility in our training sessions. TAACT domains by AAMC have given a pathway for cultural competency education but do not assess skills gained from interventions and their impact on a student’s knowledge or abilities.19 Furthermore, they do not suggest teaching strategies. As previously reported, educators have limited access to objective and standardized evaluation tools for cultural competence training interventions.20

Our primary aim through this study was to identify the most promising academic intervention to improve present and future health care professionals’ ability to provide culturally competent health care. The secondary aim was to estimate the present awareness and understanding of cultural competency and humility of medical students and residents and hopefully inculcate self-reflection and recognition of unconscious bias and internal stereotypes. Through the results of our sessions, we conclude that the rudimentary understanding of cultural competency and cultural humility improved after the session. Both students and residents rated the amalgamation of both didactics (lecture style) and workshop as the best method. We can concur that active learning is the preferred way for participants to learn. The comments and evaluations given by the students suggested that the entire experience was valuable and very informative.

There were identifiable limitations in the process. For example, more domains of TACCT could have been utilized in the session. In addition, the cohort of participants was limited to fourth-year medical students and internal medicine residents. We acknowledge that skill building around cultural competency is a lifelong process requiring reflection on the environments we practice in throughout our experience as health care professionals. Through this session we created awareness at all levels, including faculty members, about how culture is directly related to health care outcomes. It is hoped that this model of cultural competency will be executed by faculty members during educational discussions with medical students, ensuring that patients’ linguistic and cultural barriers are addressed. Even though this process aims at self-motivated transformational learning, guided training sessions can expedite the process. The next step for this project is to involve a larger participant cohort including third- and fourth-year medical students and residents from other departments. The ultimate goal is to inculcate this session as a part of the medical training curriculum in our institution and others.

In conclusion, the overall impact of formal training on cultural competency, along with finding internal and external barriers and recognizing unconscious stereotypes in the medical curriculum, will improve present and future health care professionals’ abilities to provide culturally competent health care with the ultimate goal of reducing health care disparities.

Disclosure statement/Funding

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds; Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold RS, Miner KR; 2000 Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology . Report of the 2000 Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. J Sch Health. 2002;72(1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K.. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210–217. doi: 10.1177/1043659615592677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day JC. Population Projections of the United States, by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1992 to 2050. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kratzke C, Bertolo M.. Enhancing students’ cultural competence using cross-cultural experiential learning. J Cult Divers. 2013;20(3):107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lie DA, Boker J, Crandall S, et al. Revising the tool for assessing cultural competence training (TACCT) for curriculum evaluation: findings derived from seven US schools and expert consensus. Med Educ Online. 2008;13:1–11. doi: 10.3885/meo.2008.Res00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payne K, Niemi L, Doris JM.. How to think about “implicit bias.” Sci Am. 2018;27:1–4. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-to-think-about-implicit-bias/. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paternotte E, Scheele F, van Rossum TR, Seeleman MC, Scherpbier AJ, van Dulmen AM.. How do medical specialists value their own intercultural communication behaviour? A reflective practice study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):222. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0727-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services . National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care. Washington, DC: Office of Minority Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okosun IS, Dever GE.. Abdominal obesity and ethnic differences in diabetes awareness, treatment, and glycemic control. Obes Res. 2002;10(12):1241–1250. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim EJ, Kim T, Conigliaro J, Liebschutz JM, Paasche-Orlow MK, Hanchate AD.. Racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis of chronic medical conditions in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1116–1123. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakullari A, Metersky ML, Wang Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare-associated infections in the United States, 2009-2011. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(Suppl 3):S10–S16. doi: 10.1086/677827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michalopoulou G, Falzarano P, Arfken C, Rosenberg D.. Physicians’ cultural competency as perceived by African American patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(9):893–899. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liaison Committee on Medical Education, Association of American Medical Colleges, and American Medical Association Council on Medical Education . Functions and Structure of a Medical School. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C, Cho K, Chu J, Yang J.. Bridging the gap: enhancing cultural competence of medical students through online videos. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(2):326–327. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9755-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishigori H, Otani T, Plint S, Uchino M, Ban N.. I came, I saw, I reflected: a qualitative study into learning outcomes of international electives for Japanese and British medical students. Med Teach. 2009;31(5):e196–e201. doi: 10.1080/01421590802516764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deliz JR, Fears FF, Jones KE, Tobat J, Char D, Ross WR.. Cultural competency interventions during medical school: a scoping review and narrative synthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):568–577. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05417-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campinha-Bacote J. Cultural competemility: a paradigm shift in the cultural competence versus cultural humility debate—part I. Online J Issues Nurs. 2019;24(1):1–4. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No01PPT20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jernigan VB, Hearod JB, Tran K, Norris KC, Buchwald D.. An examination of cultural competence training in US medical education guided by the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2016;9(3):150–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gozu A, Beach MC, Price EG, et al. Self-administered instruments to measure cultural competence of health professionals: a systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):180–190. doi: 10.1080/10401330701333654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]