Abstract

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitis is an autoimmune condition characterized by necrotizing inflammation of small vessels throughout the body. Pharmaceutical agents have been noted as an emerging etiology. This case presents a 41-year-old woman with a longstanding history of Graves’ disease who previously failed other interventions and was started on propylthiouracil (PTU) nearly 2 years prior to symptom onset. The patient presented with severely pruritic purpuric lesions on her lower extremities that transformed into large bullae and became extremely painful. A thorough workup revealed only slightly elevated perinuclear ANCA and a mild protein S deficiency. Tissue biopsy was consistent with thrombotic vasculitis. A presumptive clinical diagnosis of PTU-induced vasculitis was made. Because the condition is relatively uncommon, the best course of treatment has not clearly been defined. Though PTU was immediately discontinued, the patient also required corticosteroids and referral for tissue debridement. While some cases have had symptom resolution after cessation of PTU, this case adds to a growing body of evidence for the timely use of corticosteroids in controlling PTU-induced vasculitis.

Keywords: ANCA, case report, Graves’ disease, propylthiouracil, vasculitis

CASE SUMMARY

A 41-year-old woman with a history of Graves’ disease with proptosis and ophthalmic deviation, who previously failed radioiodine ablation and methimazole and had been actively managed on propylthiouracil (PTU) for 2 years, was transferred from an outside emergency department with diffuse, purpuric macules of various sizes on her lower extremities. She reported that these lesions appeared nearly 10 days earlier and were initially pruritic and limited to her upper extremities. She had been evaluated by her primary care physician 1 week before her arrival at our facility and provided a referral to dermatology. The lesions steadily increased in size, began coalescing, and had become painful, rather than pruritic, which prompted evaluation in the emergency department (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial skin findings upon presentation to the outside hospital emergency department: (a) posterior bilateral lower extremities and (b) left lateral lower extremity.

During the few hours in the emergency room, new lesions began to appear; the lesions became larger and began to transform into fluid-filled bullae (Figure 2). Given this progression, the initial concern was for purpura fulminans, but the differential diagnosis also included drug-induced vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, Henoch Schonlein purpura, and infection. Blood cultures were drawn, broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated, and PTU was held. The progression of her skin changes seemed to slow with the discontinuation of PTU, although new macules continued to develop at areas of trauma/friction.

Figure 2.

Progression of skin findings 36 hours after arrival to the emergency department: (a) posterior right leg, (b) right lateral leg, (c) right medial leg, and (d) left medial leg.

Given her history of PTU use and negative workup for purpura fulminans, drug-induced vasculitis was suspected. High-dose corticosteroids were started, and the patient’s clinical status improved. Her perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA) titer was elevated (1:640). A mild protein S deficiency was noted along with positive lupus anticoagulant, likely due to PTU use. Other laboratory tests including protein C activity, factor V activity, rheumatoid factor, antithrombin III activity, beta-2 glycoprotein I, cardiolipin, cryoglobulin, anti-nuclear antibody, fibrinogen, and D-dimer were within normal limits. Punch skin biopsy was consistent with thrombotic vasculopathy.

The patient was treated with a month-long steroid taper. She was evaluated 1 month after diagnosis and reported worsening drainage from the wounds as well as concern for necrotic tissue (Figure 3). She continued to require daily narcotic pain medication for months and required close observation and debridement by the wound care team. About 4 months after cessation of PTU, she no longer required pain medication, and many of the lesions had completely healed. Five months later, she underwent a total thyroidectomy after failing multiple treatments for Graves’ disease.

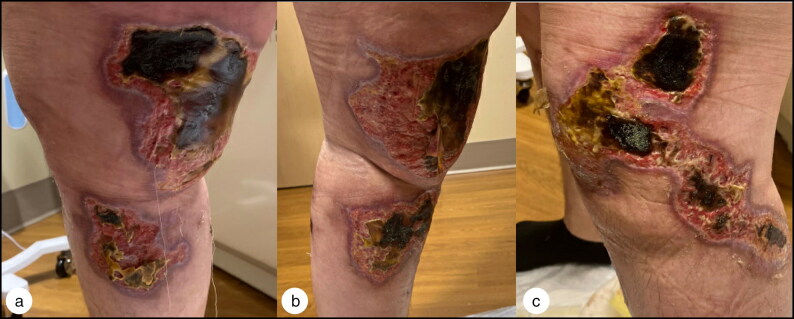

Figure 3.

Healing process after discontinuation of PTU and initiation of steroids and antibiotics, 28 days after diagnosis of PTU-induced vasculitis: (a) right medial leg, (b) left medial leg, and (c) left lateral leg.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

-

What is the most likely prognosis of PTU-induced vasculitis with limited skin involvement after appropriate treatment?

Complete resolution upon discontinuation of PTU

Continuing lesions requiring treatment with cyclophosphamide

Chronic vasculitis

Relapse within a year

-

What laboratory finding is most commonly associated with a diagnosis of purpura fulminans?

Protein S deficiency

Protein C deficiency

Elevated platelet count

Elevated transaminase

Correct answers are given at the end of the article.

DISCUSSION

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)–associated vasculitis is an autoimmune condition characterized by necrotizing inflammation of small vessels throughout the body. Pharmaceutical agents have been noted as an emerging etiology of such conditions, with antithyroid drugs being one of the top offenders. PTU is a common treatment for hyperthyroidism and has been associated with both drug-induced lupus as well as vasculitis.

This case is one of a growing number of ANCA-positive vasculitis cases associated with PTU use, which was initially recognized in 1992.1 An exact causal link has not been identified; however, the vasculitis is thought to develop as a result of PTU interaction with myeloperoxidase.2 Although cases have been reported as long as 36 months after initiating PTU treatment,3 most cases are noted sooner.4 Reported clinical findings include fever, myalgia, ocular signs, purpuric nonblanching skin lesions, hematuria, hemoptysis, and acute kidney injury.5 Interestingly, our patient’s symptoms began as severe pruritus, which has not been reported in previous cases. Early detection of this condition is critical, as worsening vasculitis has been associated with alveolar hemorrhage1 and end-organ damage.6

In some cases, the vasculitis resolves after cessation of PTU; however, accurate assessment of the best available treatment is limited due to the rarity of the condition.7 While the progression of the patient’s symptoms slowed once PTU was stopped, corticosteroids were required to achieve resolution of the symptoms. Since steroids were started shortly after the discontinuation of PTU, we cannot exclude the possibility of primary vasculitis. However, given her clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and continued remission after cessation of PTU, drug-induced vasculitis is more likely. With successful treatment, reports of relapse have not occurred up to 55 months following cessation of treatment.7 Long-term use of corticosteroids has not been shown to be required for control of symptoms.2

It is important to note that this patient’s workup revealed a mild protein S deficiency and elevated lupus anticoagulant. Given the paucity of data on PTU-induced vasculitis, and more specifically the incidence of co-occurrence of coagulopathy and PTU-induced vasculitis, we cannot eliminate the possibility that these derangements may have contributed to her condition. Further studies to investigate this correlation may be warranted.

In conclusion, early recognition of PTU-induced vasculitis is crucial given the rapid progression of the condition seen in this patient. Furthermore, this case indicates the variability of early symptoms and severity of skin findings that may occur without organ involvement. A presumptive diagnosis of PTU-induced vasculitis was made given the negative infectious workup and abatement of symptoms with the discontinuation of PTU. While some cases have had symptom resolution after cessation of PTU, this case adds to a growing body of evidence for the timely use of corticosteroids in controlling PTU-induced vasculitis. Finally, this case highlights the importance of close follow-up for resolution of both vasculitis and thyroid findings and for the development of secondary skin infections. Although PTU-induced vasculitis is rare, clinical suspicion for it should remain regardless of the length of time the patient has been taking medication, to prevent serious sequelae from this condition.

ANSWERS FOR CLINICAL QUESTIONS

1, A; 2, B.

Funding Statement

The authors report no funding or competing interests. The patient granted permission to publish this report detailing her clinical case as well as photographs.

Disclosure statement/Funding

The authors report no funding or competing interests. The patient granted permission to publish this report detailing her clinical case as well as photographs.

References

- 1.Chen B, Yang X, Sun S, et al. Propylthiouracil-induced vasculitis with alveolar hemorrhage confirmed by clinical, laboratory, computed tomography, and bronchoscopy findings: a case report and literature review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(4):e23320. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.23320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen M, Gao Y, Guo X-h, Zhao M-h.. Propylthiouracil-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(8):476–483. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomkins M, Tudor RM, Smith D, Agha A.. Propylthiouracil-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and agranulocytosis in a patient with Graves’ disease. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2020;2020:19–0135. doi: 10.1530/EDM-19-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almeida MS, Ramalho C, Gomes F, Ginga MDR, Vilchez J.. Propylthiouracil-induced skin vasculitis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27073. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross DS. Thionamides: Side effects and toxicities. UptoDate 2022.

- 6.Bilge NSY, Kaşifoğlu T, Korkmaz C.. PTU-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis: an innocent or a life-threatening adverse effect? Rheumatol Int. 2013; 33(1):117–120. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, Chen M, Ye H, Yu F, Guo X-h, Zhao M-H.. Long-term outcomes of patients with propylthiouracil-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic auto-antibody-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology. 2008;47(10):1515–1520. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]