Abstract

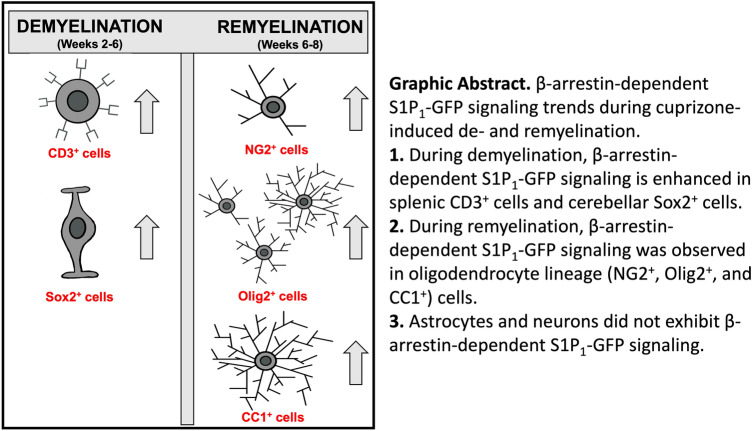

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory-demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) mediated by aberrant auto-reactive immune responses. The current immune-modulatory therapies are unable to protect and repair immune-mediated neural tissue damage. One of the therapeutic targets in MS is the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) pathway which signals via sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors 1–5 (S1P1-5). S1P receptors are expressed predominantly on immune and CNS cells. Considering the potential neuroprotective properties of S1P signaling, we utilized S1P1-GFP (Green fluorescent protein) reporter mice in the cuprizone-induced demyelination model to investigate in vivo S1P – S1P1 signaling in the CNS. We observed S1P1 signaling in a subset of neural stem cells in the subventricular zone (SVZ) during demyelination. During remyelination, S1P1 signaling is expressed in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the SVZ and mature oligodendrocytes in the medial corpus callosum (MCC). In the cuprizone model, we did not observe S1P1 signaling in neurons and astrocytes. We also observed β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling in lymphocytes during demyelination and CNS inflammation. Our findings reveal β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocyte lineage cells implying a role of S1P1 signaling in remyelination.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10571-022-01245-0.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Demyelination, Oligodendrocyte, Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1, GFP reporter mice

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive, inflammatory-demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) affecting more than two million young adults worldwide (Baecher-Allan et al. 2018; Collaborators 2019). Chronic neuroinflammation results in myelin loss, axonal damage, and eventually neurodegeneration (Conforti et al. 2014; Rotshenker 2011). The failure of remyelination leads to progressive MS and represents an unmet need for myelination enhancing therapies. Current immune-modulatory therapies successfully suppress relapses but fail to halt progressive and irreversible disability. Recognizing mechanisms that dictate demyelination and repair in the CNS is essential for limiting CNS injury, enhancing repair, and preventing permanent damage.

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a signaling molecule with significant regulatory functions in normal physiology and disease progression, particularly in the cardiovascular, central nervous, and immune systems. S1P and its receptors (S1P1-5) are crucial targets for immune regulatory functions such as lymphocyte development, regression, and adaptive immune response (Blaho and Hla 2014; Cyster and Schwab 2012). S1P receptors are expressed ubiquitously in CNS cells (Groves et al. 2013; Nishimura et al. 2010). Previous reports reveal that astrocytes express S1P1,2,3,5, oligodendrocytes express S1P1,3,5, and microglia express S1P1,2,3,5 (Groves et al. 2013; O'Sullivan and Dev 2017; Soliven et al. 2011). However, the mechanism of S1P signaling in the CNS remains unclear due to receptor diversity, variation in expression levels, different signaling pathways, and complex signaling functions. The recognition of S1P signaling in the CNS is essential since multiple S1P receptor-specific modulators are in the pipeline for treating neurological disorders. Additionally, clinical studies suggest that S1P receptor modulators directly affect the CNS beyond their immune-modulatory function. For instance, Fingolimod (FTY720) is an S1P1,3,4,5 modulator and a first-line immune-modulatory therapy for relapsing–remitting MS (Khatri 2016). Fingolimod enhances the production of various neuroprotective factors such as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in microglia (Noda et al. 2013) while also increasing GABAergic transmission, cortical parvalbumin-positive interneurons, axonal growth, and regeneration (Anastasiadou and Knoll 2016; Gentile et al. 2016; Szepanowski et al. 2016).

In MS, Fingolimod protects the brain from atrophy and halts disability progression—a feature which is absent from many contemporary therapies (De Stefano et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2020). EXPAND studies indicate that Siponimod, a selective S1P1,5 modulator, could reduce neurological injuries and progression of brain atrophy in secondary progressive MS (Benedict et al. 2021; Leavitt and Rocca 2021). Additionally, the increase in S1P levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and decrease of S1P in white matter and CNS lesions of MS patients further support the involvement of S1P signaling in neurodegeneration and inflammation (Kulakowska et al. 2010; Qin et al. 2010). These findings strongly suggest dysregulation of S1P signaling in MS. Further, they imply that S1P targeting drugs may have direct beneficial effects on the CNS, independent of their immune-modulatory function.

The present study aimed to investigate S1P1 (S1P receptor 1) β-arrestin signaling during demyelination and repair in the CNS using GFP-signaling mice, a compelling model used to reveal CNS signaling pathways. The cuprizone-induced demyelination model is a well-accepted model of CNS de- and remyelination in the absence of overwhelming CNS inflammation caused by the peripheral immune response. In this study, S1P1-GFP-signaling mice were exposed to a cuprizone diet for six weeks to induce demyelination, followed by remyelination upon reintroduction to a regular diet. To analyze S1P1-GFP signaling in the context of inflammatory demyelination, we utilized Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice.

Our results revealed that a subtype of neural stem cells (Sox2+ cells) in the SVZ express S1P1 signaling upon cuprizone-induced demyelination. During remyelination, a subpopulation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (NG2+ cells) and mature oligodendrocytes (CC1+ cells) express S1P1. No significant S1P1 signaling was identified in neurons and astrocytes during de- or remyelination. In both the cuprizone and the EAE models, a significant increase in lymphocyte (T and B cells) S1P1 signaling was revealed by flow cytometry. In both models, myeloid cells showed aberrant GFP expression in GFP reporter mice. Therefore, S1P1-GFP-signaling mice are an appropriate model for analyzing S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocyte lineage cells during remyelination and lymphocytes during both demyelination and inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

The Tango design mice were used to monitor S1P1 signaling (S1P receptor 1), and signaling was visualized through the GFP reporter gene (Kono et al. 2014). This model can detect S1P1 signaling through β-arrestin interaction. In the Tango design mice, S1P1 activation and coupling with β-arrestin released the tetracycline-controlled transactivator (tTA) from the C terminal of S1P1. tTA subsequently activates the histone-EGFP reporter gene (H2B-GFP), which produces a green signal (Kono and Proia 2015; Kono et al. 2014). The S1P1 reporter mice were designed and developed by Kono et al. (Kono et al. 2014; Kono and Proia 2015). Knock-in (ki) mice (S1P1ki/ki) were generated with two fusion genes—S1Pr1 linked to tTA via a TEV protease cleavage site and mouse β-arrestin linked to TEV protease gene. We crossed S1P1ki/ki mice with histone-EGFP reporter mice (H2B-GFP; Tg(tetO-HIST1H2BJ/GFP)47Efu/J; The Jackson Laboratory) to derive the S1P1-GFP-signaling mice.

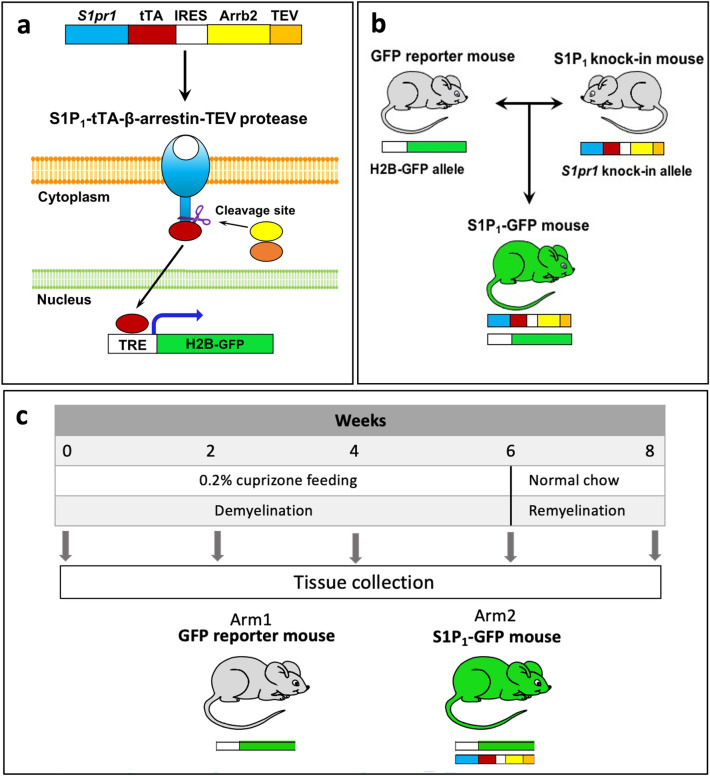

The transgenic mice expressed the histone H2B-GFP controlled by a tetracycline-responsive element (TRE) upstream of a CMV promoter (Fig. 1a, b). GFP reporter mice with one allele of the H2B-GFP reporter gene were used as a control group in our experiments. We used heterozygous knock-in allele (S1P1ki/wt) mice with one allele of the H2B-GFP reporter gene to assay S1P1 signaling in all experiments. These mice showed no phenotypic abnormalities. The mice were housed in groups of 3–5 within a 12-h light/dark cycle at a controlled temperature with food and water provided ad libitum. All the animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University. In this study, animal protocols 26,917, 21,746, and 21,747 were used and approved by the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC) at Stanford University.

Fig. 1.

Generation of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice using the Tango system. a Diagram depicting the generation of the S1pr1 knock-in allele. The S1pr1 knock-in vector is constructed using two sets of fusion genes, TEV protease cleavage site and tTA linked to S1P1 C terminal, and β-arrestin-2 linked to TEV protease (Arrb2-TEV). The two fusion genes are connected via an IRES segment. S1P-S1P1 interaction results in the coupling of S1P1 with β-arrestin-TEV protease fusion protein and initiates the release of tTA from the C terminus of modified S1P1. Free tTA transfers to the nucleus and initiates GFP expression in histone-EGFP reporter (H2B-GFP) mice. Diagram

adapted from Kono et al. (2014). b S1P1 knock-in mice are crossed with H2B-GFP mice to generate S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. c Experimental design of the cuprizone-induced demyelination model. Arrb2; β-arrestin-2, TEV; Tobacco etch virus, tTA; tetracycline-controlled transactivator, IRES; internal ribosome entry site, GFP; Green fluorescence protein, S1pr1; S1P receptor 1 gene, S1P1; S1P receptor 1

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The S1P1 knock-in genotypes were determined using PCR analyses of genomic DNA isolated from mouse tails. For genotyping by PCR, three primers were used, including 5′AGAGGAATGTGGGCTGTTGATCCT3′ (primer one for knock-in), 5′AGATGGCGGTAACTCGAGG3′ (primer two for the wild type), and 5′GGTTAGTGGTTGGCGATTAAATGCTGA3′ (primer three as reverse). Primers one and three detected the S1P1 knock-in allele and amplified a 612-bp fragment. Primers two and three detected the wild-type allele and amplified a 405-bp fragment. In total, 40 cycles of 95 °C (30 s), 62 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (45 s) were used for the amplification of these DNA segments. In addition, we detected the GFP reporter by the two primers, 5′TGTTCTGCTGGTAGTGGTCG3′ (reverse) 5′GCACCATCTTCTTCAAGGACG3′ (forward), with a PCR product of 270 bp.

Cuprizone Experiments

The knock-in S1P1-GFP signaling (H2B-GFP/S1P1ki/wt) and H2B-GFP reporter (control) mice were fed with 0.2% cuprizone (TD.140800, ENVIGO) for 6 weeks followed by two weeks of standard chow. We collected brain and spleen tissues at sequential time points during the cuprizone diet (weeks 0, 2, 4, and 6) and after 2 weeks of standard chow (week 8) (Fig. 1c). We used male mice aged 3–5 months for all the experiments (6 mice/group for immunohistochemistry and 3–6 mice/group for flow cytometry tests). GFP reporter (H2B-GFP) and S1P1-GFP (S1P1 knock-in gene with H2B-GFP gene) mice were randomly assigned and fed standard chow or cuprizone for 2 to 6 weeks.

Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) Stain

LFB was applied to brain sections to assess the loss of myelin. Brain tissues were placed in 0.1% LFB at 60 °C overnight and then rinsed with 95% ethyl alcohol and distilled water. 0.05% lithium carbonate solution was used to differentiate the stained tissues for 10–30 s, and further differentiation was performed with 70% ethyl alcohol for 10 s. Slides were counterstained with cresyl violet and dehydrated with 75%, 95%, and 100% alcohol, cleared in xylene, and then covered by a coverslip.

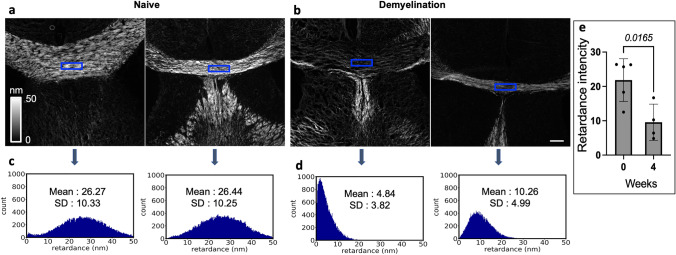

Quantitative Label-free Imaging

We used quantitative label-free imaging with phase and polarization (QLIPP) to measure the density and alignment of molecular assemblies in the myelin sheath in terms of retardance. Retardance is the differential delay experienced by light polarized along the axis of the axon and perpendicular to the axon. The measurements of the retardance in single axons (de Campos Vidal et al. 1980), rhesus monkey CNS (Blanke et al. 2021), and other studies have established that retardance provides a label-free readout of the degree of myelination in the brain tissue sections. Retardance reports the accumulated differential optical path length along two orthogonal orientations of axons at every pixel, which corresponds to the density of myelin (Guo et al. 2020). Figure 3 employs the QLIPP method to analyze the density of myelin in the medial corpus callosum (MCC) without a fluorescence label. The MBP staining involves a lipid extraction step, which can alter the level of myelin in the sample. Using a label-free measurement, we ensure that the antibody-labeling process does not perturb the level of myelin in the tissue section.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative label-free microscopy validates cuprizone-induced demyelination. Retardance due to anisotropy of myelin in the MCC of (a) two naïve and (b) two cuprizone diet-fed (4 weeks) in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. Higher retardance implies higher myelination. The grayscale color bar indicates the range of retardance measurement in the nanometer unit (0–50 nm). The histograms of the signals from the blue-box areas in the MCC of brain sections show the Mean ± SD of the retardance of myelin (nm) in (c) naïve mice (from images in a) and (d) 4 weeks cuprizone diet-fed mice (from images in b). The Y-axis of the histogram represents the number of pixels in the bin with ∼ 0.3 nm. Scale bar, 200 µm. e The graph represents the intensity of retardancy in myelin in the MCC of naïve and 4 weeks cuprizone diet in S1P1-signaling mice. (n = 4–5 mice/group, n = 9 total mice). Statistical significance was determined by an unpaired t-test (p < 0.05). The variance homogeneity, F (DFn Dfd), was 1.391 (4, 3). MCC; Medial Corpus Callosum

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane. We used a bell jar or equivalent chamber to deliver isoflurane to the mice in a fume hood. For a 1-L bell jar and 5% isoflurane, we soaked the cotton or gauze with 0.26 ml isoflurane and placed one animal at a time in the jar and closed the cap tightly. Mice perfused with 25 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS) into the left cardiac ventricle, followed by 25 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS solution. Brains were post-fixed with 4% PFA for 12–16 h and then transferred to 30% sucrose solution at 4 °C for 2–3 days until the tissue sank to the bottom of the container. Afterward, we embedded the brain tissues in a tissue-freezing medium (Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound 4583, Sakura) and stored them at − 80 °C. A cryostat-microtome (Leica CM 1850, Huston TX) was used for tissue sectioning (12 um) at -20 °C. The slides were then stored at − 20 or − 80 °C until further use.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to assess S1P1 signaling in glial and neuronal cells during demyelination and repair. We used several antibodies, including MBP (AB7349, Abcam,1/300), CD68 (MCA1957GA, AbD Serotec, 1/300), Sox2 (AB5603, Millipore,1/250), Olig2 (MABN50, Millipore,1/400), NG2 (AB5320, Millipore,1/200), GFAP (Z0334, DAKO,1/700), NeuN (MAB377, Millipore,1/250), CC1 (OP80, Calbiochem,1/300), EDG1 (ab23695 Abcam,1/150), and GFP (1020, Aves lab 1/1000). Before staining, the slides were preserved at 37 °C for 15–30 min and washed twice in PBST (PBS + Tween-20 [0.1%]) for five minutes each time.

Olig2 and CC1 were stained using sodium citrate buffer (10 Mm, PH = 6) and heat-induced antigen retrieval method. Nonspecific signaling was blocked using 5% serum (normal goat serum [G9023, Sigma]), and the sections were incubated using antibodies diluted in PBS-Tween-20 (0.1%) + 1% goat serum and preserved at 4 °C overnight. Secondary antibodies, anti-rat Alexa Fluor 555 (A21434, Invitrogen, 1/1000), anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (A21428, Invitrogen, 1/1000), anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 (A21424, Invitrogen, 1/1000), anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (A32728, Invitrogen, 1/1000), and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (A27040, Invitrogen, 1/1000) were used for labeling. In addition, staining was performed without primary antibodies to exclude the non-specific signaling caused by the secondary antibodies. The validation and specificity of antibodies for the immunohistochemistry test are presented in Supplementary Table 1S.

The slides were then counterstained with DAPI and covered with a coverslip. A Keyence microscope (BZ-X700 series) was used to evaluate staining and take pictures. The cells were counted in 0.1 mm2 of medial corpus callosum (MCC) and subventricular zone (SVZ) and then normalized to DAPI. We utilized the ImageJ software for cell counting and intensity measurements. Additionally, blind and manual counting was performed using ImageJ.

EAE Experiments

EAE was induced in male S1P1–GFP-signaling mice and GFP reporter mice aged 8–12 weeks. According to methods defined by Tsai et al. (2016, 2019), mice were immunized with an emulsion containing 200 µg of Complete Freund's Adjuvant (CFA) and 100 µg of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide35–55 (MOG35-55). Subsequently, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 nanograms of Bordetella pertussis toxin (181236A1, List Biological Laboratories) on days zero and two. We collected the spleen tissues after eight days of immunization which marked the onset of the clinical EAE symptoms.

GFP Signaling in the Immune Cells Isolated from Brain and Spleen Using Flow Cytometry

Brain and spleen of cuprizone-fed mice were collected at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 6 to analyze S1P1 signaling in immune cells. To evaluate S1P1 signaling in the inflammatory state, we examined the S1P1 signaling in the spleen of EAE mice. Immune cells obtained from the brain and spleen were isolated as previously reported (Arac et al. 2011). In short, mice were anesthetized and then perfused with 25 ml cold PBS. The spleens were removed before perfusion and homogenized through a 70-μm cell strainer. Red blood cells (RBC) were lysed using ACK lysing buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 M EDTANa2.H2O 3.7) for 30–60 s and then washed with PBS; 106 cells were used for labeling with antibody.

Brains were collected after PBS perfusion and homogenized through a 70-μm cell strainer in sterile PBS before being centrifuged. The pellet was treated with collagenase II (1 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. The collagenase reaction was stopped by adding PBS to the cells and centrifugation. Immune cells were harvested from a 30% Percoll gradient by centrifugation, and residual red blood cells lysed by ACK lysing buffer for 5–10 s. The immune cells were washed with PBS, and 0.5–1 × 106 cells were labeled with individual antibodies and analyzed using the LSRII Flow Cytometer (BD) at the Stanford core Facility. We used BD FACS Diva 6.0 software to acquire data and FlowJo for data analysis (Tree Star).

The monoclonal antibodies used in flow cytometry analysis were purchased from the following sources: anti CD45 (552,848, clone 30-F11, BD pharmingen), anti-CD3 (557,596, clone 145-2C11, BD Pharmingen), anti CD4 (100,432, clone GK1.5, Biolegend), anti CD8 (553,030, clone 53–6.7, BD Pharmingen), anti CD19 (115,512, clone 6D5, Biolegend), anti-CD11b (101,269, clone M1/70, Biolegend), anti-CD11c (12–01,114-82, clone N418, TermoFisher), anti-Ly6C (128,013, clone HK1.4, Biolegend), and anti-Ly6G (127,613, clone 1A8, Biolegend). The validation and specificity of antibodies for the flow cytometry experiments are presented in Supplementary Table 2S.

To set compensation and gate the stained cells, we used single color-stained BD-CompBeads (BD Bioscience). CNS immune cells were gated by multi-dimensional flow cytometry. First, cells were gated into CD45lo and CD45hi from live leukocytes. CD45lo cells represent microglia, and CD45hi represent infiltrating immune cells (Supplementary Fig. 1S). CD45hi cells were gated to CNS-infiltrating myeloid cells (CD45hiCD11b+) and lymphocytes (CD45hiCD3+). Infiltrating myeloid cells (CD45hiCD11b+) were further gated to monocyte-derived dendritic cells (CD45hiCD11b+Cd11c+) and myeloid cells (CD45hiCD11b+CD11c−). Afterward, CD11b+CD11c− myeloid cells were separated into neutrophils (Ly6C−Ly6G+) and monocytes (Ly6C+Ly6G−). GFP expression was assessed in brain myeloid cells (CD45hiCD11b+), granulocytes (CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6G+), and lymphocytes (CD45hiCD3+). Splenic cells were gated as myeloid cells (CD45+CD11b+) and lymphocytes (CD45+CD3+), and we assessed GFP expression in splenic myeloid cells and lymphocytes. In EAE mice, splenic cells were collected as outlined above and gated as myeloid cells (CD45+CD11b+), T cells (CD45+CD3+), and B cells (CD45+CD19+).

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the data with GraphPad Prism 9 and used ImageJ for quantification of cell numbers. To determine normality, we used the Shapiro–Wilk test. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests were used to determine the significant difference between the groups. Ordinary One-Way ANOVA, a parametric test, was used for groups with equal variance and normal distribution. We used the Brown-Forsyth test for the groups with unequal variance and normal distribution. In a non-normal distribution, we used Kruskal–Wallis, a nonparametric test, to analyze the variance between the groups. We used Benjamini and Hochberg's original False discovery rate (FDR) method as a post-hoc for correction of the multiple comparisons.

Additionally, we used the unpaired t test with Welch's correction to compare the difference between the two groups with normal distribution. Mann–Whitney, a nonparametric test, was used for non-normal distribution. For all data analysis, statistical significance was determined by calculating the FDR adjusted p value (q value) (p < 0.05). In each graph, the results are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) in normal distributed groups and median with interquartile range in non-normal distribution groups.

Power Calculations for Sample Size

We performed power calculations to determine the number of mice per experiment. To calculate the sample size in our study, we used the previous study published by Kono et al. (2014). They studied S1P1 signaling in an inflammatory mouse model by LPS-induced inflammation. We also used a power calculator from Mass General Hospital with two-sided 0.05 significance level and minimal detectable difference 2 units (Schoenfeld 2005). The software calculated a sample size of 6 mice per experimental arm at a power of 0.85.

Results

Validation of Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination in S1P1-GFP-Signaling Mice

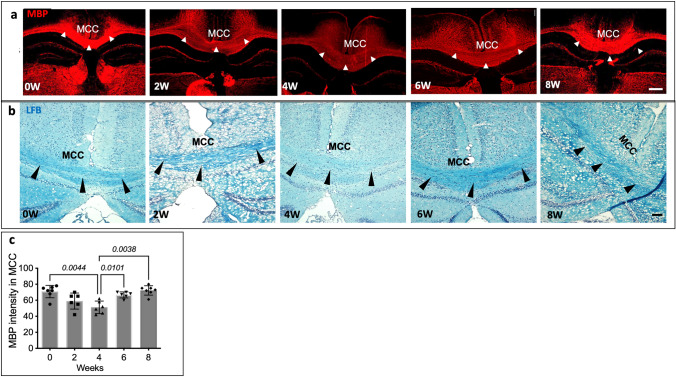

Cuprizone is known to cause immediate damage to the oligodendrocytes leading to demyelination (Benardais et al. 2013). To validate demyelination in the S1P1-GFP-signaling mice following exposure to the cuprizone diet, we measured myelin basic protein (MBP) intensity in the medial corpus callosum (MCC). Additionally, oligodendrocytes in the MCC were counted. We used ImageJ for cell counting and measuring MBP intensity. In our MBP assay, the Shapiro–Wilk test showed normal distribution in the groups, and equality of group variance was determined by the Brown-Forsythe test (F = 9.175, DFn = 4.00, and DFd = 20.06). Our results indicated a significant decrease in MBP intensity in the MCC after 4 weeks of the cuprizone diet, p = 0.0044 (Fig. 2a, c). LFB staining indicated a reduction in myelin after 4 weeks of the cuprizone diet (Fig. 2b). Additionally, we used a quantitative label-free imaging method to measure the optical anisotropy (retardance) for visualizing the distribution of myelin in MCC without a label. Recent research has found that the optical anisotropy arises from ordered molecular structures such as myelin (Guo et al. 2020). Label-free imaging of myelination indicates a significant difference in retardance (myelination level) in MCC after 4 weeks of cuprizone diet (p = 0.0165) (Fig. 3). Shapiro–Wilk test showed normal distribution in two groups. Therefore, we used an unpaired t test to assess the significant difference between the two groups (F = 1.391, DFn = 4, and Dfd = 3).

Fig. 2.

Validation of cuprizone-induced demyelination in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. a MBP staining, via immunohistochemistry of the brain depicting de/remyelination in the MCC (arrowheads) of S1P1-GFP signaling mice following exposure to cuprizone diet (0–8 weeks). Scale bar, 200 µm. b LFB staining depicting myelin density in the MCC (arrowhead) of S1P1-GFP mice upon cuprizone exposure (0–8 weeks), Scale bar, 100 µm. c Quantification of MBP intensity in the MCC of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice fed with cuprizone diet from (a), (n = 6 mice/group, n = 60 total mice). The values are presented as Mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests were used to determine the significant differences in MBP intensity in S1P1-signaling mice at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of cuprizone fed (p < 0.05). The variance homogeneity, F (DFn Dfd), was 9.175 (4.000, 20.06). MCC; Medial Corpus Callosum, LFB; Luxol Fast Blue, MBP; Myelin Basic Protein

The number of oligodendrocytes decreased significantly during the second week of the cuprizone treatment before being restored to normal levels at 4 weeks, p < 0.0001. (Supplementary,Fig. 2S-a, b). Shapiro–Wilk test showed normal distribution in all groups and equality of group variance determined by the Brown-Forsythe test (F = 11.06, DFn = 4.000, and DFd = 14.58).

Another crucial pathological feature of cuprizone-induced demyelination was astrogliosis, the peak of which was after 4 weeks of cuprizone diet (Supplementary, Fig. 3S-a). We observed active myeloid cells (CD68+ cells) in the corpus callosum (CC), hippocampus, amygdala, caudoputamen, and septofimberial nucleus at 2 weeks of cuprizone diet (Supplementary, Fig. 3S-b). Furthermore, CD68+ cell density increased in the CC, hippocampus, primary somatosensory cortex, caudoputamen, and preoptic area at 4 weeks of cuprizone diet. After 6 weeks of cuprizone diet, CD68+ cells were present in the CC, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus. At 8 weeks (remyelination), we identified CD68+ cells in the CC, deep layer of the cortex, thalamus, and dorsal hippocampal commissure. In total, myelin loss, astrogliosis, reduced oligodendrocyte number, and increased CD68+ cells confirmed the effects of cuprizone on S1P1-GFP-signaling mice.

GFP Signaling in the CNS During Cuprizone-induced De- and Remyelination

Based on the Tango design, we are able to visualize S1P1 signaling via GFP expression. S1P1-GFP signaling was analyzed in CNS glia and neurons during demyelination following exposure to the cuprizone diet (weeks 0–6) and upon remyelination (standard diet weeks 6–8) (Fig. 1c). The number of GFP+ cells increased during the cuprizone diet in the CC. After 2 weeks, GFP+ cells appeared in the brain and increased at 4, 6, and 8 weeks. The cells in the lateral corpus callosum (LCC) and MCC of the S1P1-GFP-signaling mice displayed the highest expression of GFP (Supplementary, Fig. 4S-a, c). GFP signaling was also identified in the LCC and MCC of the GFP reporter mice at various time points of the cuprizone diet (Supplementary, Fig. 4S-b, d). In quantification of GFP+ cells in the MCC of control and S1P1-signaling mice, GFP reporter mice showed significantly fewer GFP + cells in the MCC than GFP-S1P1-signaling mice at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of the cuprizone diet with p = 0.0365, p = 0.0288, and p = 0.0377, respectively (Supplementary, Fig. 4S-e).

GFP Signaling in the CNS Cells During Demyelination and Repair

We then investigated S1P1 signaling in neurons and CNS glia of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice during cuprizone-induced de- and -remyelination. In the following four subsections, we assessed GFP expression in oligodendrocytes, neuronal stem cells, astrocytes, neurons and CNS myeloid-lineage cells.

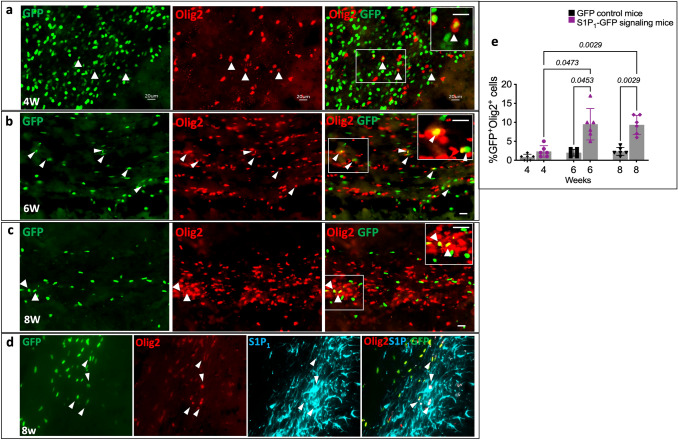

S1P1-GFP Signaling in Oligodendrocytes During Remyelination

S1P1 plays a crucial role in oligodendrocyte morphology and differentiation (Coelho et al. 2007; Dukala and Soliven 2016; Jung et al. 2007; Miron et al. 2008). We quantified the number of Olig2+ cells in the MCC of cuprizone-fed S1P1-GFP-signaling mice by immunohistochemistry. The MCC of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice showed a significant decrease in the number of oligodendrocytes at two weeks of cuprizone diet and reached normal levels at 8 weeks.

A small percentage of the GFP+ cells (2.33 ± 1.50%) in the MCC of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice were positive for Olig2 after 4 weeks of cuprizone diet (Fig. 4a, e). After 6 and 8 weeks of cuprizone diet, 9.50 ± 4.13% and 9.33 ± 2.5% of total GFP+ cells were Olig2+ in MCC, respectively (Fig. 4b, c, e). However, in GFP reporter mice, we found only 2.0 ± 0.89% and 2.33 ± 1% of the total GFP+ cells were Olig2+ at 6 and 8 weeks of cuprizone diet, respectively (Fig. 4e). Oligodendrocytes in MCC of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice express significantly higher GFP at 6 and 8 weeks of the cuprizone diet than GFP reporter mice with p = 0.0453 and p = 0.0029, respectively. The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated normal distribution in all groups and homogeneity of variance analyzed by the Brown-Forsythe test (F = 13.06, DFn = 7.000, and DFd = 21.76). Olig2+ cells in CC express higher GFP in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice compared to GFP reporter mice. We used heat-induced antigen retrieval for CC1 and Olig2 staining. Heating masked the GFP in the tissue, so we used an anti-GFP antibody. We validated the specificity of the GFP antibody in naïve S1P1-signaling mice. Naïve S1P1-signaling mice did not stain with GFP antibody, but S1P1-GFP-signaling mice at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks cuprizone diet showed GFP expression equivalent to the tissue without heat-induced antigen retrieval (Supplementary Fig. 5S-a). To verify the specificity of GFP signaling, we performed S1P1 (EDG1) staining, and most of the GFP+Olig2+ cells were positive for S1P1 (Fig. 4d). We validated the specificity of S1P1 antibody using the brain tissue of S1P1 knockout mouse (Supplementary Fig. 5S-b).

Fig. 4.

S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocytes depicted by GFP expression during remyelination. a Immunohistochemistry of oligodendrocytes (Olig2+) in the MCC of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice at 4 weeks, (b) 6 weeks, and (c) 8 weeks following exposure to cuprizone diet. White arrowheads indicate GFP expression colocalizing with Olig2+ cells. Scale bars, 20 µm. Magnification of S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocytes is depicted in the upper right corner. d S1P1 and Olig2 staining in the SVZ of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice at 8 weeks of cuprizone diet. White arrowheads represent GFP expression in Olig2+S1P1+ cells. The image on the right shows a higher magnification of GFP expression in Olig2+NG2+ cells. (e) Quantification of GFP+Olig2+ to the total GFP+ cells in 0.1 mm2 of MCC of the control and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice (n = 6 mice/group, n = 60 total mice). ImageJ was used for counting the cells. The values presented as Mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests were used to determine the significant differences in Olig2+GFP+ cells between the GFP reporter and S1P1-signaling mice in each time point of cuprizone fed and in each group of mice during the cuprizone fed (4, 6, and 8 weeks) (p < 0.05). The variance homogeneity F (DFn, Dfd) was 19.85 (5.000, 11.62) for GFP-Olig2. SVZ; Subventricular Zone. MCC; Medial Corpus Callosum, OPCs; Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells and NG2; Neural-Glial Antigen

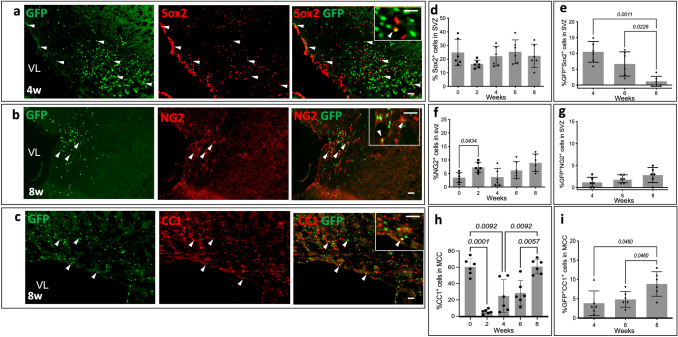

Sox2, a critical transcription factor in neural stem cells, is essential for oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) proliferation and oligodendrocyte regeneration following myelin impairment in the adult brain (Zhang et al. 2018). Oligodendrocytes express NG2 in the early stage of their development. However, NG2+ cells can differentiate to gray matter astrocytes and pericytes (Ozerdem et al. 2001; Polito and Reynolds 2005; Zhu et al. 2008). Sox2 and NG2 staining were performed along with quantification of cells with GFP expression. S1P1 signaling was distinguished in 5% of Sox2+ cells in the SVZ of cuprizone-fed mice during demyelination (4 weeks) (Fig. 5a). The number of the Sox2+ cells decreased in the SVZ at the 2-week point of the cuprizone diet, but the change was not statistically significant (Fig. 5d). 10.50 ± 3.27% and 6.66 ± 3.8% of the total GFP+ cells in SVZ were Sox2+ in 4 and 6 weeks cuprizone diet, respectively, but Sox2+ cells did not express significant S1P1 signaling during remyelination (Fig. 5e). GFP expression in Sox2+ cells decreased significantly at 8 weeks compared to 4 and 6 weeks cuprizone diet p = 0.0011 and p = 0.0226, respectively.

Fig. 5.

S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells detected by GFP expression. The images represent S1P1 signaling in (a) Sox2+ (b) NG2+ and (c) CC1+ cells in SVZ of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice at 4 (a) and 8 (b and c) weeks following exposure to cuprizone. Arrowheads indicate colocalization with the GFP signal. The upper right corner images depict a higher magnification of S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocytes. The graphs represent the percentage of (d) Sox2+, (f) NG2+ and (h) CC1 cells in 0.1 mm2 of SVZ in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice, which normalized by DAPI. The percentage of (e) GFP+Sox2+, (g) GFP+NG2+ and (i) GFP+CC1+ cells of total GFP+ cells per 0.1 mm2 during cuprizone diet (0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks), (n = 6 mice/groups, n = 60 total mice). The values are presented as Mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests were used to determine the significant differences in S1P1-signaling mice at each time point of cuprizone fed (p < 0.05), Scale bars, 20 µm. Variance Homogeneity, F (DFn Dfd), were: Sox 2 = 1.257 (4.000, 20.26), Sox2-GFP = 14.18 (2.000, 11.60), NG2 = 4.055 (4.000, 22.09), NG2-GFP = 2.435 (2.000, 11.65), CC1 = 20.84 (4.000, 14.62), and CC1-GFP = 5.143 (2.000, 13.39). SVZ; Subventricular Zone. NG2; Neural-Glial Antigen 2., VL; Lateral Ventricle

Approximately 70% of the NG2+ cells in the SVZ of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice were Olig2+ cells during remyelination (Supplementary Fig. 6S). Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (NG2+Olig2+) express GFP during remyelination (Fig. 5b). NG2+ cells in the SVZ increased at 2 weeks, p = 0.043 (Fig. 5f). NG2+ cells were negative for GFP signaling at 2 weeks of cuprizone diet, whereas around 2.8% of GFP+ cells were NG2+ in the SVZ at 8 weeks (Fig. 5g). These experiments indicate Sox2+ cells expressed GFP during demyelination while NG2+ cells expressed GFP during remyelination.

CC1 (a marker for mature oligodendrocytes) staining was performed to analyze GFP expression in mature oligodendrocytes. CC1+ cells decreased significantly at 2 weeks cuprizone diet (p = 0.0001) and reached to normal at 8 weeks. The Shapiro–Wilk test showed normal distribution in all groups in CC1 staining, and homogeneity of variance was evaluated by the Brown-Forsythe test (F = 20.84, DFn = 4.000, and DFd = 14.62). GFP expression in mature oligodendrocytes increased significantly at 8 weeks cuprizone diet (p = 0.0460). 8.8 ± 3.2% of the GFP+ cells in 0.1 mm2 of MCC were CC1-positive at 8-weeks of experimental period (Fig. 5c, h). The Shapiro–Wilk test showed normal distribution in all groups for our CC1-GFP experiments and homogeneity of variance was analyzed by the Brown-Forsythe test (F = 5.143, DFn = 2.000, and DFd = 13.39).

In conclusion, we found S1P1 signaling in immature oligodendrocytes progenitor cells (NG2+) in the SVZ and mature oligodendrocytes (CC1+) in the MCC during remyelination. The Olig2+GFP+ cells may represent S1P1 signaling through β-arrestin in oligodendrocytes.

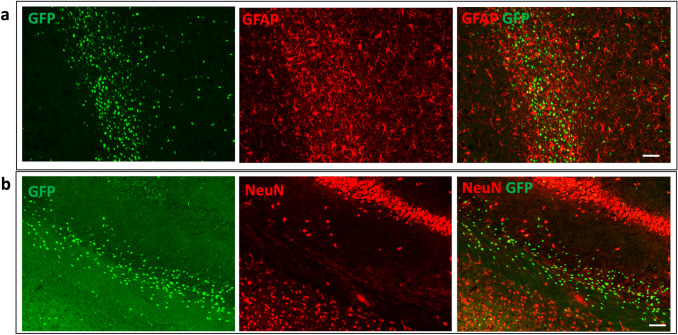

No Significant S1P1 Expression in Astrocytes During De- and Remyelination

Previous studies have shown that Fingolimod (FTY720), an S1P1-3–4-5 modulator, has the ability to downregulate NF-κB signaling in astrocytes, thereby decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic mediators (Rothhammer et al. 2017). Besides Fingolimod, other compounds such as SEW2871 can act as a selective S1P1 agonist and stimulate astrocyte migration (Mullershausen et al. 2007). To determine the correlation of GFP expression with S1P1 signaling in astrocytes, we performed GFAP staining. GFAP+ cells did not express GFP signaling during de- and remyelination (weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8) (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Lack of GFP expression in astrocytes and neurons in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice during cuprizone diet. The images indicated. (a) Astrocytes (GFAP+) and (b) NeuN+ cells were GFP negative in the LCC of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice at 4 weeks of cuprizone diet. Scale bars, 50 µm (a and b). LCC; Lateral Corpus Callosum

S1P1 Signaling Is not Detected in Mature Neurons

Previous reports indicated that the S1P1-3–4-5 modulator, FTY720, suppressed neuronal injury and improved cognition after cerebral ischemia (Czech et al. 2009). In our study, we further investigated the role of neuronal S1P1 signaling during demyelination and repair. An immunofluorescence test with NeuN staining was performed, but S1P1 signaling was not detected in the neurons of the CC, hippocampus, and cortex (Fig. 6b).

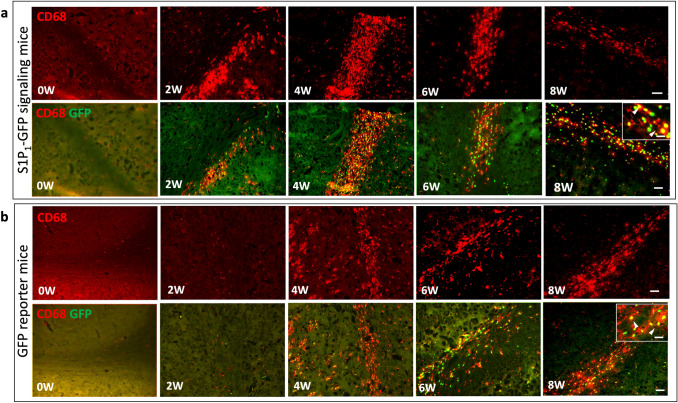

Myeloid Cell-S1P1 Signaling in S1P1-GFP-Signaling Mice During De- and Remyelination

Our previous research indicated that myeloid S1P1 signaling plays a crucial role in CNS autoimmunity and neuroinflammation (Tsai et al. 2019). Previous reports suggest that S1P1 regulates pro and anti-inflammatory microglia (M1/M2) polarization, and a study by Gaire (2019) demonstrated that the suppression of S1P1 activity attenuates M1 polarization and induces the M2 phenotype (Gaire et al. 2019). Considering the vital role of S1P1 in microglia polarization, we investigated S1P1 signaling in CNS myeloid-lineage cells, infiltrating monocytes, and microglia. CD68 immunofluorescence staining was performed on brain sections of cuprizone-fed mice at sequential time points (weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8). At two weeks of cuprizone diet, almost 94% of GFP+ cells in CC were positive for CD68, whereas at weeks 4, 6, and 8, only 79–75-80% of GFP+ cells also expressed CD68+ in CC, respectively (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Fig. 7S). Unexpectedly, we also observed GFP expression in CD68+ cells of GFP reporter mice at 4, 6, and 8 weeks of cuprizone diet (Fig. 7b). The colocalization of GFP and CD68 in GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice indicates that GFP signaling is not associated with S1P1 signaling. Naïve GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice did not express GFP; however, following exposure to cuprizone diet, myeloid cells in both groups expressed GFP signaling.

Fig. 7.

GFP expression in myeloid cells of S1P1-GFP signaling and GFP reporter mice upon cuprizone exposure. GFP expression in myeloid cells (CD68+) in the LCC of (a) S1P1-GFP-signaling mice and (b) GFP reporter mice at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 weeks of the cuprizone diet. In the upper right corner higher magnification of GFP expression in CD68+ cells are shown. Scale bars, 50 µm and 20 µm for images with higher magnification. LCC; Lateral Corpus Callosum

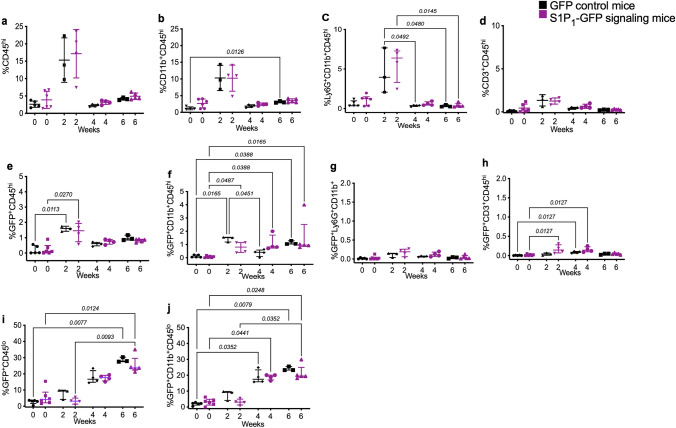

To validate the study’s outcomes, we examined myeloid cells and lymphocytes in the brain and spleen of mice with cuprizone-induced demyelination using flow cytometry. Supplementary Fig. 1S represents the gating strategy for CNS immune cells. The number of CNS-infiltrating myeloid cells (CD45hiCD11b+), lymphocytes (CD45hiCD3+), and granulocytes (CD45hi CD11b+Ly6G+) increased at 2-week of cuprizone diet, but it was not statistically significant. However, both GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice expressed GFP in myeloid cells and granulocytes. Lymphocytes (CD3+) showed higher but not statistically significant GFP signaling in the brain of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice than the GFP reporter mice after 2 and 4 weeks of cuprizone diet (Fig. 8c, g, and Supplementary Fig. 8S-c, g). GFP expression in microglia (CD45lo CD11b+) increased significantly in GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP signaling at 4 weeks cuprizone-fed with p = 0.0352 and p = 0.0441, respectively (Fig. 8i, j and Supplementary Fig. 8S-i, j).

Fig. 8.

Flow cytometry analysis of S1P1 signaling via GFP expression in cerebral immune cells upon cuprizone-induced demyelination. GFP expression in cerebral immune cell subpopulations upon cuprizone exposure (0, 2, 4, and 6 weeks) in GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. a Infiltration of immune cells (CD45hi), (b) myeloid cells (CD11b+CD45hi), (c) granulocytes (LyG+CD45hi) and (d) lymphocytes (CD3+CD45hi) into the brain during demyelination (0–6 weeks) in S1P1-GFP signaling and GFP reporter mice. (e) GFP expression in infiltrating immune cells (CD45hi), (f) myeloid cells (CD11b+CD45hi), (g) granulocytes (LyG+CD45hi) and (h) lymphocytes (CD3+CD45hi) in GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice during demyelination. GFP expression in (i) resident microglia (GFP+CD45lo) and (j) activated microglia (GFP+CD45lo CD11b+) in GFP reporter and signaling mice. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests were used to analyze the significant differences between the GFP reporter and S1P1-signaling mice at each time point of the cuprizone diet and significant changes in each group of mice during cuprizone fed (p < 0.05) (3–6 mice/group, n = 34 total mice). The values are presented as Mean ± SD in the a, b, and d graphs. Kruskal–Wallis was used for nonparametric graphs, and the values presented as median with interquartile range in c, e, f, g, h, I, and j graphs. Variance homogeneity, F (DFn Dfd) in normal distributed groups: CD45hi = 10.85 (7.000, 5.785), CD11b = 12.19 (7.000, 5.662), Ly-6G, CD3 = 7.699 (7.000, 6.452). Ly-6G, CD45hi-GFP, CD11b-GFP, Ly-6G-GFP, CD3-GFP, CD45lo-GFP, CD45lo, and CD11b-GFP groups exhibited non-normal distribution

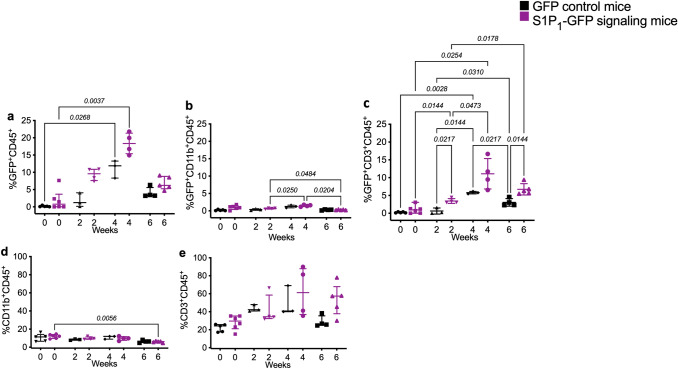

The experiments on brain tissues could not confirm whether GFP leakiness was limited to CNS myeloid cells. Therefore, we decided to assess splenic myeloid cells and lymphocytes in GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling cuprizone-fed mice using flow cytometry. Myeloid cells (CD45+CD11b+) decreased significantly in the spleen at 6 weeks of cuprizone diet in S1P1-signaling mice with p = 0.0056. However, no significant difference was observed in the GFP+CD11b+ cells between GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. The CD3+ cells increased in the spleen after 2 weeks of the cuprizone diet but were not statistically significant. Remarkably, GFP+CD3+ cells were significantly more abundant in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice than GFP reporter mice after 2 and 6 weeks of cuprizone diet p = 0.0217 and **p = 0.0144, respectively (F = 19.005, DFn = 7.000, and DFd = 5.229) (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. 9S).

Fig. 9.

Flow cytometry analysis of S1P1 signaling via GFP expression in splenic immune cells upon cuprizone-induced demyelination. a GFP expression in leukocytes (CD45+), (b) myeloid cells (CD11b+) and (c) lymphocytes (CD3+) in the spleens of S1P1-GFP signaling and GFP reporter mice following exposure to cuprizone diet (0–6 weeks). (d) Percentage of myeloid cells (CD11b+) and (e) lymphocytes (CD3+) in CD45+ population during cuprizone diet. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests were used to analyze the significant differences between the GFP reporter and S1P1-signaling mice in each time point of cuprizone diet and significant changes in each group of mice during cuprizone fed (p < 0.05) (3–6 mice/group, n = 34 total mice). The values presented as Mean ± SD in b and c graphs. Kruskal–Wallis was used for nonparametric graphs and the values presented as median with interquartile range in a, d and e graphs (Supplementary Table 3S). The variance homogeneity, F (DFn, Dfd) were: CD11b-GFP = 11.58 (7.000, 12.80), CD3-GFP = 19.05 (7.000, 5.229). CD45-GFP, CD11b, and CD3 exhibited non-normal distribution

Confirmation of S1P1 Expression in Immune Cells in the EAE Model

We investigated myeloid S1P1 signaling in EAE mice. To characterize S1P1 signaling in myeloid cells and lymphocytes during inflammation, we used flow cytometry. While splenic myeloid cells (CD45+CD11b+) expressed high levels of GFP in both the EAE GFP reporter and S1P1-GFP-signaling mice (Supplementary Fig. 10S), GFP expression was significantly higher in splenic lymphocytes of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. Splenic B (CD19+) and T cells (CD3+) of EAE mice expressed significantly higher GFP signaling compared to the control group during inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 11S).

Discussion

S1PR1-5 modulators, such as Fingolimod and Siponimod, reduce neurological injuries and progression of brain atrophy in secondary progressive MS, but mechanisms underlying S1P signaling in the CNS cells are not understood well. The complexity of S1PR1-5 signaling assessment results from ubiquitous expression in various cell types and the initiation of different signaling pathways through association with different G proteins, which employ various cell behaviors. Nevertheless, each receptor subtype's expression levels, function, and mechanism in neurons and glial cells during demyelination, neurodegeneration, and repair remain elusive. This study used S1P1-GFP-signaling mice to analyze β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling in the CNS during de- and remyelination using a cuprizone model. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze S1P1 signaling in vivo via GFP expression in CNS cells during de- and remyelination. Since S1P1 knockout mice exhibited embryonic hemorrhage leading to the death at the embryonic stage (Blaho and Hla 2011; Kono et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2000), it is not possible to use S1P1 knockout mice to understand further the molecular and cellular mechanisms of S1P1 signaling in CNS.

One of the contemporary research objectives is to determine if oligodendrocytes express S1P1 signaling during toxic insult and repair. According to the literature, oligodendrocyte lineage cells express S1P receptors. For instance, FTY720 regulates the survival and maturation of OPCs (Coelho et al. 2007; Miron et al. 2008). S1P1 conditional knockout mice reduced myelin thickness in the CC, and S1P1‐deficient oligodendrocytes had slower process extension (Dukala and Soliven 2016). However, another study indicates that cuprizone feeding does not increase cell death in S1P1‐deficient oligodendrocytes (Kim et al. 2011). S1P1 signaling is essential for neural stem cell mobilization and migration to the sites of CNS injury and plays a significant role in oligodendrocytes differentiation (Alfonso et al. 2015; Kimura et al. 2007; Yazdi et al. 2018). Also, Sox2 is crucial for oligodendrocyte proliferation and differentiation in the adult brain (Yazdi et al. 2018). Therefore, S1P1 signaling in neural stem cells (Sox2+ cells) during demyelination suggests a role in the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells to oligodendrocytes and migration of neural stem cells to the site of injury. Our results showed S1P1 signaling in immature and mature oligodendrocytes during remyelination (Fig. 5e, g, i) which may implicate S1P1 signaling in differentiation, maturation, survival, and morphology of oligodendrocytes. Heterogeneity in oligodendrocyte lineage cells and dynamics of oligodendrocyte differentiation and maturation (Marques et al. 2016; Yeung et al. 2014) may be the reason for β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling in a subpopulation of oligodendrocytes. In support of our findings related to MS, other studies have reported a decrease of S1P in the white matter and CNS lesions of MS patients. Furthermore, fingolimod prevents brain atrophy and halts disability progression, and Siponimod reduces neurological injuries and progression of brain atrophy in secondary progressive MS.

Previous studies reported protective effects of S1P1 signaling in neurons after ischemic stroke (Hasegawa et al. 2010). Furthermore, S1P1 signaling regulates glutamate secretion and synaptic transmission (Kajimoto et al. 2007). However, in our study, β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling was not detected in neurons during de- and remyelination. S1P1 signaling is essential for switching the intermediate/transition astrocytes to reactive astrocytes (Groves et al. 2018). Hypertrophic astrocytes in the brain lesions of MS patients express S1P1 (Choi et al. 2011; Van Doorn et al. 2010). However, the high arborization and density of astrocytes during demyelination made it challenging to determine the exact number of the GFP+GFAP+ cells via immunofluorescence. To overcome this difficulty in our analyses, we only counted GFP+GFAP+ cells when GFP was in the cell body of the astrocytes rather than around the arborization. Nevertheless, S1P1 signaling was not distinguished significantly in astrocytes of S1P1-GFP-signaling mice. Low levels of S1P1 expression or reduced turnover of neurons and astrocytes may interpret the absence of GFP signaling in these cells. Also, β-arrestin independent signaling and involvement of other S1P receptor subtypes (such as S1P3) may account for the lack of S1P1 signaling in neurons and astrocytes reported here (Zamanian et al. 2012).

S1P1 is the primary S1P receptor expressed in immune cells and plays a pivotal role in immune cell function, development, and trafficking. S1P1 signaling regulates lymphocyte exit from secondary lymphatic organs into the systemic circulation (Cyster and Schwab 2012; Rivera et al. 2008). Moreover, S1P1 is essential for transferring immature B cells from the bone marrow to the circulation (Allende et al. 2010). In our research, lymphocytes and myeloid cells were examined in the brain and spleen of mice with cuprizone-induced demyelination using flow cytometry. Remarkably, splenic lymphocytes (CD3+) expressed significantly higher levels of GFP in S1P1-GFP-signaling mice than in the GFP reporter mice. For that reason, another objective of our study was to determine whether GFP expression was specific in lymphocytes during inflammation. To this end, we used EAE mice as an inflammatory animal model of MS. We found specific GFP signaling in splenic T cells and B cells (CD3+ and CD19+) during inflammation in the EAE GFP-S1P1-signaling mice compared to GFP reporter mice. In addition, the subpopulations of T cells, CD8+, and CD4+ cells expressed significantly higher S1P1 signaling in EAE GFP-S1P1-signaling mice than in GFP reporter mice. These results demonstrated increased S1P1 signaling in splenic lymphocytes during demyelination and inflammation in a β-arrestin-dependent manner. Previous studies have shown increased S1P concentration in the CSF of MS subjects. Higher levels of S1P in the CSF may provoke immune cell trafficking in the CNS and inhibit T(reg) function via β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling (Liu et al. 2009; Maeda et al. 2015).

β-arrestin-dependent signaling promotes internalization and downregulation of S1P1 in lymphocytes leading to lymphocyte egress, enhanced autoimmune responses, and a worse prognosis for CNS inflammation in MS (Matloubian et al. 2004). However, S1P-S1P1 signaling in the CNS cells is not well understood. Our findings suggest that β-arrestin-dependent S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocytes promotes differentiation and likely enhances the myelination process. These results imply a beneficial role of S1P1 signaling in oligodendrocytes. Activated β-arrestin affects multiple components of the kinase cascade and propagates specific signaling pathways (Jean-Charles et al. 2017; Pyne and Pyne, 2017). Consequently, S1P1- β-arrestin signaling can create different cell behaviors in CNS glial and immune cells. Therefore, further studies need to investigate the mechanisms downstream of S1P1-β-arrestin signaling in oligodendrocytes and assess if it is different from lymphocytes.

Several preclinical studies have demonstrated the effects of S1P signaling on microglia. For example, FTY720 upregulates the brain-derived neurotrophic factor and downregulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia (Noda et al. 2013). In myeloid cells, S1P1 signaling is critical in the polarization of M1/M2 macrophages (Muller et al. 2017). Our previous research demonstrated that continuous S1P1 signaling in myeloid cells mediates TH17 polarization (Tsai et al. 2019). GFP expression in GFP reporter mice should be silent in the absence of tTA. However, our immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry tests indicated aberrant expression of the transgene in the activated myeloid cells of GFP reporter mice after EAE and cuprizone-induced demyelination. Additionally, previous studies have identified GFP leakage in hematopoietic stem cells in H2B-GFP reporter mice (Challen and Goodell 2008; Morcos et al. 2020). Putative GFP leakage prevents us from drawing any conclusions regarding S1P1-GFP signaling in CNS-resident and peripheral myeloid cells. Several studies have reported the accuracy and reliability of the S1P1-GFP signaling murine model (Cartier et al. 2020; Kono et al. 2014). However, none of these studies investigated CNS inflammations and activated myeloid cells. The causes of the aberrant GFP expression in the absence of the tTA protein remain unclear. It is possible that the H2B-GFP transgene was integrated into a region of DNA in the myeloid cells, switching the transcriptional activity by the cuprizone diet or EAE induction. H2B-GFP protein in the nucleosome may affect the chromatin structure and gene expression in the activated myeloid cells in our findings regarding the potential leakiness of GFP. Nonspecific binding to the synthetic promoter in activated microglia may be another cause of the GFP leakiness. S1P could also act as an intracellular messenger and bind to nuclear S1P1, which inhibits the activity of histone deacetylase 1 and 2 (HDAC1/2), thereby resulting in epigenetic regulation of gene expression (Ebenezer et al. 2017; Fu et al. 2018). Modulation of HDAC1/2 by nuclear S1P1 may also account for the GFP leakiness in myeloid cells.

In summary, our results indicate that the S1P1 signaling in the oligodendrocyte lineage during remyelination may have a protective effect by regulating myelination in response to injury. Elucidating regulatory mechanisms downstream of S1P1- β-arrestin signaling in oligodendrocytes will provide important evidence to design effective therapies for demyelinating diseases like MS. S1P1 was not significantly expressed in neurons and astrocytes, possibly because S1P1 signaling in CNS neurons and astrocytes is not dependent on β-arrestin. S1P1 signaling was identified in lymphocytes during demyelination and inflammation. In this regard, S1P1-GFP-signaling mice could be used to analyze the anti-inflammatory role of CD3+ cells, as well as the role of B cells in neurodegeneration and repair in EAE and cuprizone models.

Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence revealed GFP leakage in myeloid cells upon EAE induction and cuprizone exposure in GFP reporter mice, which complicates the interpretation of the results. It is essential to generate new lines of H2B-GFP reporter mice to establish appropriate reporter for the analysis of myeloid cells.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues Nora Sandrine Wetzel and Anna Tomczak for manuscript critical review.

Abbreviations

- CC

Corpus Callosum

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CP

Caudo-Putamen

- CTX

Cortex

- EAE

Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

- GFAP

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

- GFP

Green Fluorescence Protein

- GPCR

G Protein-Coupled Receptor

- HDAC1/2

Histone Deacetylase 1 and 2

- IRES

Internal Ribosome Entry Site

- LCC

Lateral Corpus Callosum,

- LFB

Luxol Fast Blue

- MBP

Myelin Basic Protein

- MCC

Medial Corpus Callosum

- MS

Multiple Sclerosis

- NG2

Neural/Glial Antigen

- OPCs

Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells

- QLIPP

Quantitative Label-free Imaging with Phase and Polarization

- S1P

Sphingosine-1-Phosphate

- S1pr1

S1P receptor 1 gene

- S1P1

S1P receptor 1

- S1PR1-5

Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors 1–5

- SVZ

Subventricular Zone

- TEV

Tobacco Etch Virus

Author Contributions

EH: designed and performed the experiments, analyzed, and interpreted the data, made figures, and wrote the manuscript. EY performed IHC experiments, imaging, helped make figures, and did cell counting. H-CT performed EAE experiments and helped in flowcytometry tests and analysis. MM collaborated in tissue collection and data acquisition. LHY and SBM analyzed myelin by label-free imaging. MK and RP provided S1P1-GFP-signaling mice and contributed to the final manuscript. MH.H designed the experiments, analyzed, and interpreted the data and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Foundation Leducq and a training grant from National Institutes of Health on infection, Immunity, and Inflammation (T32 AI 7290–32).

Data Availability

Please contact the authors for data requests.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All methods and animal procedures were performed in accordance with The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University.

Consent to Participant

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alfonso J, Penkert H, Duman C, Zuccotti A, Monyer H (2015) Downregulation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promotes the switch from tangential to radial migration in the OB. J Neurosci 35(40):13659–13672. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1353-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende ML, Tuymetova G, Lee BG, Bonifacino E, Wu YP, Proia RL (2010) S1P1 receptor directs the release of immature B cells from bone marrow into blood. J Exp Med 207(5):1113–1124. 10.1084/jem.20092210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadou S, Knoll B (2016) The multiple sclerosis drug fingolimod (FTY720) stimulates neuronal gene expression, axonal growth and regeneration. Exp Neurol 279:243–260. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arac A, Brownell SE, Rothbard JB, Chen C, Ko RM, Pereira MP, Albers GW, Steinman L, Steinberg GK (2011) Systemic augmentation of alphaB-crystallin provides therapeutic benefit twelve hours post-stroke onset via immune modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(32):13287–13292. 10.1073/pnas.1107368108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baecher-Allan C, Kaskow BJ, Weiner HL (2018) Multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and immunotherapy. Neuron 97(4):742–768. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benardais K, Kotsiari A, Skuljec J, Koutsoudaki PN, Gudi V, Singh V, Vulinovic F, Skripuletz T, Stangel M (2013) Cuprizone [bis(cyclohexylidenehydrazide)] is selectively toxic for mature oligodendrocytes. Neurotox Res 24(2):244–250. 10.1007/s12640-013-9380-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, Tomic D, Cree BA, Fox R, Giovannoni G, Bar-Or A, Gold R, Vermersch P, Pohlmann H, Wright I, Karlsson G, Dahlke F, Wolf C, Kappos L (2021) Siponimod and cognition in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: EXPAND secondary analyses. Neurology 96(3):e376–e386. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaho VA, Hla T (2011) Regulation of mammalian physiology, development, and disease by the sphingosine 1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid receptors. Chem Rev 111(10):6299–6320. 10.1021/cr200273u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaho VA, Hla T (2014) An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Lipid Res 55(8):1596–1608. 10.1194/jlr.R046300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanke N, Go V, Rosene DL, Bigio IJ (2021) Quantitative birefringence microscopy for imaging the structural integrity of CNS myelin following circumscribed cortical injury in the rhesus monkey. Neurophotonics 8(1):015010. 10.1117/1.NPh.8.1.015010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier A, Leigh T, Liu CH, Hla T (2020) Endothelial sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors promote vascular normalization and antitumor therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(6):3157–3166. 10.1073/pnas.1906246117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challen GA, Goodell MA (2008) Promiscuous expression of H2B-GFP transgene in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS ONE 3(6):e2357. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JW, Gardell SE, Herr DR, Rivera R, Lee CW, Noguchi K, Teo ST, Yung YC, Lu M, Kennedy G, Chun J (2011) FTY720 (fingolimod) efficacy in an animal model of multiple sclerosis requires astrocyte sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(2):751–756. 10.1073/pnas.1014154108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho RP, Payne SG, Bittman R, Spiegel S, Sato-Bigbee C (2007) The immunomodulator FTY720 has a direct cytoprotective effect in oligodendrocyte progenitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323(2):626–635. 10.1124/jpet.107.123927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborators GBDMS (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18(3):269–285. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30443-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L, Gilley J, Coleman MP (2014) Wallerian degeneration: an emerging axon death pathway linking injury and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 15(6):394–409. 10.1038/nrn3680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster JG, Schwab SR (2012) Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol 30:69–94. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Pfeilschifter W, Mazaheri-Omrani N, Strobel MA, Kahles T, Neumann-Haefelin T, Rami A, Huwiler A, Pfeilschifter J (2009) The immunomodulatory sphingosine 1-phosphate analog FTY720 reduces lesion size and improves neurological outcome in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 389(2):251–256. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Campos Vidal B, Mello ML, Caseiro-Filho AC, Godo C (1980) Anisotropic properties of the myelin sheath. Acta Histochem 66(1):32–39. 10.1016/S0065-1281(80)80079-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano N, Silva DG, Barnett MH (2017) Effect of fingolimod on brain volume loss in patients with multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 31(4):289–305. 10.1007/s40263-017-0415-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukala DE, Soliven B (2016) S1P1 deletion in oligodendroglial lineage cells: effect on differentiation and myelination. Glia 64(4):570–582. 10.1002/glia.22949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer DL, Fu P, Suryadevara V, Zhao Y, Natarajan V (2017) Epigenetic regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) in acute lung injury: role of S1P lyase. Adv Biol Regul 63:156–166. 10.1016/j.jbior.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu P, Ebenezer DL, Ha AW, Suryadevara V, Harijith A, Natarajan V (2018) Nuclear lipid mediators: role of nuclear sphingolipids and sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in epigenetic regulation of inflammation and gene expression. J Cell Biochem 119(8):6337–6353. 10.1002/jcb.26707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaire BP, Bae YJ, Choi JW (2019) S1P1 regulates M1/M2 polarization toward brain injury after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Biomol Ther (seoul). 10.4062/biomolther.2019.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile A, Musella A, Bullitta S, Fresegna D, De Vito F, Fantozzi R, Piras E, Gargano F, Borsellino G, Battistini L, Schubart A, Mandolesi G, Centonze D (2016) Siponimod (BAF312) prevents synaptic neurodegeneration in experimental multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 13(1):207. 10.1186/s12974-016-0686-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A, Kihara Y, Chun J (2013) Fingolimod: direct CNS effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulation and implications in multiple sclerosis therapy. J Neurol Sci 328(1–2):9–18. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A, Kihara Y, Jonnalagadda D, Rivera R, Kennedy G, Mayford M, Chun J (2018) A functionally defined in vivo astrocyte population identified by c-Fos activation in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis modulated by S1P signaling: immediate-early astrocytes (ieAstrocytes). eNeuro. 10.1523/ENEURO.0239-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo SM, Yeh LH, Folkesson J, Ivanov IE, Krishnan AP, Keefe MG, Hashemi E, Shin D, Chhun BB, Cho NH, Leonetti MD, Han MH, Nowakowski TJ, Mehta SB (2020) Revealing architectural order with quantitative label-free imaging and deep learning. Elife. 10.7554/eLife.55502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y, Suzuki H, Sozen T, Rolland W, Zhang JH (2010) Activation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 by FTY720 is neuroprotective after ischemic stroke in rats. Stroke 41(2):368–374. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Charles PY, Kaur S, Shenoy SK (2017) G Protein-coupled receptor signaling through beta-arrestin-dependent mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 70(3):142–158. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG, Kim HJ, Miron VE, Cook S, Kennedy TE, Foster CA, Antel JP, Soliven B (2007) Functional consequences of S1P receptor modulation in rat oligodendroglial lineage cells. Glia 55(16):1656–1667. 10.1002/glia.20576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimoto T, Okada T, Yu H, Goparaju SK, Jahangeer S, Nakamura S (2007) Involvement of sphingosine-1-phosphate in glutamate secretion in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Biol 27(9):3429–3440. 10.1128/MCB.01465-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri BO (2016) Fingolimod in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: long-term experience and an update on the clinical evidence. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 9(2):130–147. 10.1177/1756285616628766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Miron VE, Dukala D, Proia RL, Ludwin SK, Traka M, Antel JP, Soliven B (2011) Neurobiological effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulation in the cuprizone model. FASEB J 25(5):1509–1518. 10.1096/fj.10-173203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Ohmori T, Ohkawa R, Madoiwa S, Mimuro J, Murakami T, Kobayashi E, Hoshino Y, Yatomi Y, Sakata Y (2007) Essential roles of sphingosine 1-phosphate/S1P1 receptor axis in the migration of neural stem cells toward a site of spinal cord injury. Stem Cells 25(1):115–124. 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono M, Proia RL (2015) Imaging S1P1 activation in vivo. Exp Cell Res 333(2):178–182. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono M, Allende ML, Proia RL (2008) Sphingosine-1-phosphate regulation of mammalian development. Biochim Biophys Acta 1781(9):435–441. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono M, Tucker AE, Tran J, Bergner JB, Turner EM, Proia RL (2014) Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 reporter mice reveal receptor activation sites in vivo. J Clin Invest 124(5):2076–2086. 10.1172/JCI71194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulakowska A, Zendzian-Piotrowska M, Baranowski M, Kononczuk T, Drozdowski W, Gorski J, Bucki R (2010) Intrathecal increase of sphingosine 1-phosphate at early stage multiple sclerosis. Neurosci Lett 477(3):149–152. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt VM, Rocca M (2021) Siponimod for cognition in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: thinking through the evidence. Neurology 96(3):91–92. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, Mi Y, Deng CX, Hobson JP, Rosenfeldt HM, Nava VE, Chae SS, Lee MJ, Liu CH, Hla T, Spiegel S, Proia RL (2000) Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest 106(8):951–961. 10.1172/JCI10905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Burns S, Huang G, Boyd K, Proia RL, Flavell RA, Chi H (2009) The receptor S1P1 overrides regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression through Akt-mTOR. Nat Immunol 10(7):769–777. 10.1038/ni.1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Seki N, Kataoka H, Takemoto K, Utsumi H, Fukunari A, Sugahara K, Chiba K (2015) IL-17-producing vgamma4+ gammadelta T cells require sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 for their egress from the lymph nodes under homeostatic and inflammatory conditions. J Immunol 195(4):1408–1416. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques S, Zeisel A, Codeluppi S, van Bruggen D, Mendanha Falcao A, Xiao L, Li H, Haring M, Hochgerner H, Romanov RA, Gyllborg D, Munoz Manchado A, La Manno G, Lonnerberg P, Floriddia EM, Rezayee F, Ernfors P, Arenas E, Hjerling-Leffler J et al (2016) Oligodendrocyte heterogeneity in the mouse juvenile and adult central nervous system. Science 352(6291):1326–1329. 10.1126/science.aaf6463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG (2004) Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature 427(6972):355–360. 10.1038/nature02284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Jung CG, Kim HJ, Kennedy TE, Soliven B, Antel JP (2008) FTY720 modulates human oligodendrocyte progenitor process extension and survival. Ann Neurol 63(1):61–71. 10.1002/ana.21227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcos MNF, Zerjatke T, Glauche I, Munz CM, Ge Y, Petzold A, Reinhardt S, Dahl A, Anstee NS, Bogeska R, Milsom MD, Sawen P, Wan H, Bryder D, Roers A, Gerbaulet A (2020) Continuous mitotic activity of primitive hematopoietic stem cells in adult mice. J Exp Med. 10.1084/jem.20191284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, von Bernstorff W, Heidecke CD, Schulze T (2017) Differential S1P receptor profiles on M1- and M2-polarized macrophages affect macrophage cytokine production and migration. Biomed Res Int 2017:7584621. 10.1155/2017/7584621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullershausen F, Craveiro LM, Shin Y, Cortes-Cros M, Bassilana F, Osinde M, Wishart WL, Guerini D, Thallmair M, Schwab ME, Sivasankaran R, Seuwen K, Dev KK (2007) Phosphorylated FTY720 promotes astrocyte migration through sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. J Neurochem 102(4):1151–1161. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura H, Akiyama T, Irei I, Hamazaki S, Sadahira Y (2010) Cellular localization of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 expression in the human central nervous system. J Histochem Cytochem 58(9):847–856. 10.1369/jhc.2010.956409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Takeuchi H, Mizuno T, Suzumura A (2013) Fingolimod phosphate promotes the neuroprotective effects of microglia. J Neuroimmunol 256(1–2):13–18. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan S, Dev KK (2017) Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor therapies: advances in clinical trials for CNS-related diseases. Neuropharmacology 113(Pt B):597–607. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozerdem U, Grako KA, Dahlin-Huppe K, Monosov E, Stallcup WB (2001) NG2 proteoglycan is expressed exclusively by mural cells during vascular morphogenesis. Dev Dyn 222(2):218–227. 10.1002/dvdy.1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polito A, Reynolds R (2005) NG2-expressing cells as oligodendrocyte progenitors in the normal and demyelinated adult central nervous system. J Anat 207(6):707–716. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00454.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne NJ, Pyne S (2017) Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 signaling in mammalian cells. Molecules. 10.3390/molecules22030344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Berdyshev E, Goya J, Natarajan V, Dawson G (2010) Neurons and oligodendrocytes recycle sphingosine 1-phosphate to ceramide: significance for apoptosis and multiple sclerosis. J Biol Chem 285(19):14134–14143. 10.1074/jbc.M109.076810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A (2008) The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 8(10):753–763. 10.1038/nri2400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothhammer V, Kenison JE, Tjon E, Takenaka MC, de Lima KA, Borucki DM, Chao CC, Wilz A, Blain M, Healy L, Antel J, Quintana FJ (2017) Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulation suppresses pathogenic astrocyte activation and chronic progressive CNS inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(8):2012–2017. 10.1073/pnas.1615413114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotshenker S (2011) Wallerian degeneration: the innate-immune response to traumatic nerve injury. J Neuroinflammation 8:109. 10.1186/1742-2094-8-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld D, Borenstein M (2005) Calculating the power or sample size for the logistic and proportional hazards models. J Stat Comput Simul 75(10):771–785. 10.1080/00949650410001729445. http://hedwig.mgh.harvard.edu/sample_size/quan_measur/assoc_quant.html

- Smith PA, Schmid C, Zurbruegg S, Jivkov M, Doelemeyer A, Theil D, Dubost V, Beckmann N (2018) Fingolimod inhibits brain atrophy and promotes brain-derived neurotrophic factor in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 318:103–113. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliven B, Miron V, Chun J (2011) The neurobiology of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators. Neurology 76(8 Suppl 3):S9-14. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820d9507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szepanowski F, Derksen A, Steiner I, Meyer Zu Horste G, Daldrup T, Hartung HP, Kieseier BC (2016) Fingolimod promotes peripheral nerve regeneration via modulation of lysophospholipid signaling. J Neuroinflammation 13(1):143. 10.1186/s12974-016-0612-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HC, Huang Y, Garris CS, Moreno MA, Griffin CW, Han MH (2016) Effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 phosphorylation in response to FTY720 during neuroinflammation. JCI Insight 1(9):e86462. 10.1172/jci.insight.86462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HC, Nguyen K, Hashemi E, Engleman E, Hla T, Han MH (2019) Myeloid sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 is important for CNS autoimmunity and neuroinflammation. J Autoimmun 105:102290. 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn R, Van Horssen J, Verzijl D, Witte M, Ronken E, Van Het Hof B, Lakeman K, Dijkstra CD, Van Der Valk P, Reijerkerk A, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL, De Vries HE (2010) Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 and 3 are upregulated in multiple sclerosis lesions. Glia 58(12):1465–1476. 10.1002/glia.21021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi A, Mokhtarzadeh Khanghahi A, Baharvand H, Javan M (2018) Fingolimod enhances oligodendrocyte differentiation of transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitors. Iran J Pharm Res 17(4):1444–1457 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung MS, Zdunek S, Bergmann O, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Perl S, Tisdale J, Possnert G, Brundin L, Druid H, Frisen J (2014) Dynamics of oligodendrocyte generation and myelination in the human brain. Cell 159(4):766–774. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou L, Giffard RG, Barres BA (2012) Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J Neurosci 32(18):6391–6410. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhu X, Gui X, Croteau C, Song L, Xu J, Wang A, Bannerman P, Guo F (2018) Sox2 is essential for oligodendroglial proliferation and differentiation during postnatal brain myelination and CNS remyelination. J Neurosci 38(7):1802–1820. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1291-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xiao B, Li CX, Wang Y (2020) Fingolimod (FTY720) improves postoperative cognitive dysfunction in mice subjected to D-galactose-induced aging. Neural Regen Res 15(7):1308–1315. 10.4103/1673-5374.272617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Bergles DE, Nishiyama A (2008) NG2 cells generate both oligodendrocytes and gray matter astrocytes. Development 135(1):145–157. 10.1242/dev.004895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the authors for data requests.

Not applicable.