Abstract

The Rep78 and Rep68 proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV) are multifunctional proteins which are required for viral replication, regulation of AAV promoters, and preferential integration of the AAV genome into a region of human chromosome 19. These proteins bind the hairpin structures formed by the AAV inverted terminal repeat (ITR) origins of replication, make site- and strand-specific endonuclease cuts within the AAV ITRs, and display nucleoside triphosphate-dependent helicase activities. Additionally, several mutant Rep proteins display negative dominance in helicase and/or endonuclease assays when they are mixed with wild-type Rep78 or Rep68, suggesting that multimerization may be required for the helicase and endonuclease functions. Using overlap extension PCR mutagenesis, we introduced mutations within clusters of charged residues throughout the Rep68 moiety of a maltose binding protein-Rep68 fusion protein (MBP-Rep68Δ) expressed in Escherichia coli cells. Several mutations disrupted the endonuclease and helicase activities; however, only one amino-terminal-charge cluster mutant protein (D40A-D42A-D44A) completely lost AAV hairpin DNA binding activity. Charge cluster mutations within two other regions abolished both endonuclease and helicase activities. One region contains a predicted alpha-helical structure (amino acids 371 to 393), and the other contains a putative 3,4 heptad repeat (coiled-coil) structure (amino acids 441 to 483). The defects displayed by these mutant proteins correlated with a weaker association with wild-type Rep68 protein, as measured in coimmunoprecipitation assays. These experiments suggest that these regions of the Rep molecule are involved in Rep oligomerization events critical for both helicase and endonuclease activities.

Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV) is a human parvovirus with a single-stranded, linear DNA genome containing inverted terminal repeats which function as origins of replication (14, 40, 44, 53). AAV is nonpathogenic and usually requires an adenovirus or herpesvirus as a helper for efficient replication (7). The AAV rep gene encodes at least four overlapping multifunctional nonstructural proteins transcribed from two promoters. Rep68 and Rep78 (Rep68/78) are encoded by spliced and unspliced transcripts, respectively, from the promoter at map position 5; hence, the first 529 amino acids of Rep78 and Rep68 are identical (9, 35, 52, 56). Rep40 and Rep52 are encoded by spliced and unspliced transcripts, respectively, from the promoter at map position 19 (9, 35, 52, 56).

The terminal palindromic repeat sequences of AAV DNA fold into hairpin structures and thereby serve as primers for the synthesis of the complementary strand (8, 52). The resulting closed-end intermediates are resolved by a process called terminal resolution, which involves cutting by a site- and strand-specific endonuclease at the terminal resolution site (trs) followed by unwinding and replication of the hairpin (17, 50, 51). Rep68/78 display activities which are required for AAV DNA replication, including the ability to bind specifically to sequences within the AAV terminal hairpin DNA (17–19, 34, 38, 63) and strand-specific nicking at the trs (17, 19, 50). The larger Rep proteins also have DNA helicase (17, 19, 26) and DNA-RNA helicase activities (65), as well as ATPase activity (65). Furthermore, the Rep68/78 proteins regulate AAV promoters (4, 27, 28, 30, 55) and have been shown to regulate numerous heterologous promoters (1, 15, 29, 66, 68). They are also thought to be involved in the preferential integration of AAV genomes into a region on the q arm of human chromosome 19 (13, 23–25, 31, 46, 57, 63).

Rep68/78, like many transcriptional regulatory proteins of DNA viruses, such as the 32-kDa E1A protein of adenovirus; E1, E7, L1, and L2 of human papillomavirus; and VP2 and large T antigen of Simian virus 40, carry charge clusters in their primary sequences (for reviews, see the work of Karlin and Brendel [20, 21]). Ionic interactions of charge clusters within proteins are associated with protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions (58, 64, 72) and appear to be important in protein transport, nuclear localization, and transcriptional regulation (6).

Mapping studies of the Rep68/78 proteins by site-specific mutation, truncation, and deletion reveal that the Rep proteins are composed of distinct, but interdependent, functional domains (see Fig. 1) (33, 37, 38, 59, 60, 69). Rep68/78 DNA binding functions are believed to be bipartite, with binding specificity being associated with the first 241 amino acids (33, 38, 62, 70) and stabilizing interactions being associated with amino acids 242 to 476 (33, 38, 62, 70). The first 476 amino acids of Rep68/78 have been shown to be sufficient for nucleoside triphosphate-dependent endonuclease activity (62). The first 522 amino acids of Rep68/78 or amino acids 225 to 621 (Rep52) are sufficient for DNA helicase activity (26, 47). The observation that Rep68/78 proteins produce multiple shifted bands in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) with hairpin DNA (17–19, 33, 37, 70), along with the existence of dominant-negative mutant Rep68/78 proteins (26, 36, 59, 65) and the detection of multimeric Rep78 complexes in gel filtration, protein cross-linking, and coimmunoprecipitation experiments (48), strongly suggests that Rep68/78 proteins function as multimers.

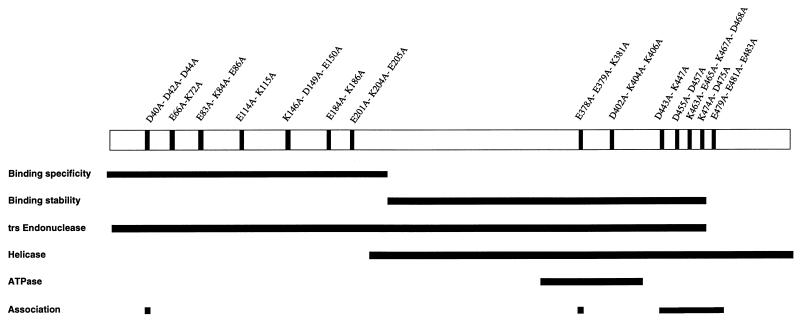

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the Rep moiety of MBP-Rep68Δ showing the locations of charge cluster mutations. The locations of the charge-to-alanine mutations are labeled and shown as vertical black bars. The horizontal black bars indicate the regions sufficient for DNA binding specificity (38), DNA binding stabilization (38, 62), trs endonuclease activity (62), and helicase activities (26, 47) and the region with homology to other ATPase and helicase proteins (22, 60). Regions suspected of being involved in oligomerization, as demonstrated in this study, are also indicated.

We have previously demonstrated that a Rep68/78 truncation mutant protein containing amino acids 1 to 476 also produces a multiple-shifted-band pattern in EMSAs with AAV hairpin DNA and that these shifted bands have a faster migration than those formed with the wild-type Rep68. When this mutant protein with amino acids 1 to 476 was mixed with wild-type Rep68, there was a loss of the distinct multiple shifted bands and instead there was a smear of protein-DNA complexes with intermediate rates of migration (62). Truncations and site-specific mutagenesis studies suggest that there are at least two separate self-association domains between amino acids 164 and 484, including a 3,4 hydrophobic heptad repeat between amino acids 164 and 182 (48) and a region between amino acids 332 and 346, which has also been shown to be important for ATPase (48, 60) and helicase activities (60).

In this study, we have mutated charged residues to alanines in areas of Rep68 with three or more charged residues within a continuous stretch of five. An overlap extension PCR method (16) was used to create these charge-to-alanine mutations in a maltose binding protein (MBP)-Rep68 fusion protein (MBP-Rep68Δ). MBP-Rep68Δ exhibits all of the functional activities reported for the wild-type Rep68 when it is assayed in vitro (10). We have assessed the effects of these mutations on AAV hairpin DNA binding, AAV trs endonuclease activity, and DNA helicase activity in vitro. In addition, these mutants were used in coimmunoprecipitation experiments with radiolabeled, in vitro-translated Rep68 in order to assess their ability to associate with wild-type Rep68.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis.

An overlap extension PCR method (16) was used to introduce site-specific substitutions within the Rep68 open reading frame. Lysine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid residues were mutated to alanine residues at various positions within the Rep68 coding sequence. Briefly, two pairs of primers were used to direct synthesis of mutated DNA fragments, with the two leading bases in the codons for lysine (AAG and AAA), aspartic acid (GAT and GAC), and glutamic acid (GAG and GAA) being converted to GC, i.e., to an alanine codon, with the least amount of deviation from the original DNA sequence (Table 1). Arginines and histidines were not mutated to alanines, because such mutations were predicted to be more likely to produce global conformational disruptions (5). These fragments, which overlapped by at least 25 bp, were gel purified and subsequently used for overlap extension PCR with 5′ and 3′ flanking primers. The resulting amplified products were gel purified and digested with appropriate restriction endonucleases, generating fragments no larger than 750 bp, each of which was substituted for the corresponding fragment within the parent plasmid bearing the genes encoding MBP-Rep68Δ (10, 16). The PCRs were carried out with the thermostable Pfu DNA polymerase, which has a high fidelity (1.3 × 10−6 errors/bp/cycle; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The resulting mutations in MBP-Rep68Δ were confirmed by sequencing, and the resulting proteins were designated by the region of mutation.

TABLE 1.

Mutant primers used for overlap extension PCR

| Sequencea | Description or mutations | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| GCGAGCCCTCAGATCCTGCATATAA | 5′ flanking primer for residues 40 through 205 | |

| CGTGGCCCATCCCAGAAAGACGGAA | 3′ flanking primer for residues 40 through 205 | |

| CCGCCAGcTTCTGcCATGGcTCTGAA | D40A-D42A-D44A | Forward |

| TTCAGAgCCATGgCAGAAgCTGGCGG | D40A-D42A-D44A | Reverse |

| TGACGGcATGGCGCCGTGTGAGTgcGGCCC | E66A-K72A | Forward |

| GGGCCgcACTCACACGGCGCCATgCCGTCA | E66A-K72A | Reverse |

| GTGCAATTTGcGgcGGGAGcGAGCTACTTC | E83A-K84A-E86A | Forward |

| GAAGTAGCTCgCTCCCgcCgCAAATTGCAC | E83A-K84A-E86A | Reverse |

| AGTCAGATTCGCgcAgcACTGATTCAGAGA | E114A-K115A | Forward |

| TCTCTGAATCAGTgcTgcGCGAATCTGACT | E114A-K115A | Reverse |

| GGGAACgcGGTGGTGGcTGcGTGCTACATC | K146A-D149A-E150A | Forward |

| GATGTAGCACgCAgCCACCACCgcGTTCCC | K146A-D149A-E150A | Reverse |

| AATCTCACGGcGCGTgcACGGTTGGTGGCG | E184A-K186A | Forward |

| CGCCACCAACCGTgcACGCgCCGTGAGATT | E184A-K186A | Reverse |

| ACGCAGGCGCAGAACGCAGCGAATCAGAAT | E201A-K204A-E205A | Forward |

| ATTCTGATTCGCTGCGTTCTGCGCCTGCGT | E201A-K204A-E205A | Reverse |

| TATGGAACAGTATTTAAGCGCCTGT | 5′ flanking primer for residues 378 through 483 | |

| GAGAGAGTGTCCTCGAGCCAATCT | 3′ flanking primer for residues 378 through 483 | |

| CTGGTGGGcGGcGGGGgcGATGACCG | E378A-E379A-K381A | Forward |

| GGCGGTCATCgcCCCCgCCgCCCAC | E378A-E379A-K381A | Reverse |

| GCGCGTGGcCCAGgcATGCgcGTCCTCGGC | D402A-K404A-K406A | Forward |

| GCCGAGGACgcGCATgcCTGGgCCA | D402A-K404A-K406A | Reverse |

| GCCGTTGCAAGcCCGGATGTTCgcATTTG | D443A-K447A | Forward |

| CAAATgcGAACATCCGGgCTTGCAACGGC | D443A-K447A | Reverse |

| CTCACCCGCCGTCTGGcTCATGcCTTTG | D455A-D457A | Forward |

| CCCAAAGgCATGAgCCAGACGGCGGGT | D455A-D457A | Reverse |

| ACCgcGCAGGcAGTCgcAGcCTTTTTCCG | K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A | Forward |

| CGGAAAAAGgCTgcGACTgCCTGCgcGGT | K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A | Reverse |

| GACTTTTTCCGGTGGGCAgcGGcTCACG | K474A-D475A | Forward |

| CGTGAgCCgcTGCCCACCGGAAAAAGTC | K474A-D475A | Reverse |

| GTGGTTGcGGTGGcGCATGcATTCTACG | E479A-E481A-E483A | Forward |

| GACGTAGAATgCATGCgCCACCgCAACCAC | E479A-E481A-E483A | Reverse |

Bold lowercase letters indicate the mutation sites. Forward oligonucleotides and their reverse complements are written 5′ to 3′. Lysine (AAA and AAG), aspartic acid (GAC and GAT), and glutamic acid (GAA and GAG) codons converted to alanine codons (GCA, GCT, GCC, and GCG) are underlined in the forward strands.

Expression of MBP-Rep68Δ and mutant proteins.

MBP-Rep68Δ and mutant derivatives were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified with amylose affinity columns as described previously (10). An MBP–β-galactosidase fusion (MBP-LacZ) was also synthesized and used as a negative control. The production of MBP-Rep68Δ proteins of the predicted molecular weights was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining. Protein concentrations were determined by observing optical density at 225 nm with bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards.

EMSAs.

EMSAs were performed as described previously (18, 60, 63). Briefly, radiolabeled AAV hairpin DNA (5,000 cpm) was incubated with 2 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ or mutant proteins in a reaction mixture (30 μl) containing 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5 μg of BSA, 0.01% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) at 24°C for 30 min. The protein-DNA complexes were resolved on a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel at 24°C, which was then dried and autoradiographed.

trs endonuclease assays.

The site- and strand-specific endonuclease assay was performed as described previously (17). AAV hairpin DNA labeled at its 5′ end with 32P (25,000 cpm) was incubated in the presence of 2 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ or a mutant protein in a 30-μl reaction volume containing 25 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2% glycerol, 0.2 μg of BSA, and 0.4 mM ATP. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and the reactions were terminated by addition of 15 μl of gel loading buffer (0.5% SDS, 50 mM EDTA, 40% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.1% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol) with subsequent boiling to release the nicked fragment. The reaction products were resolved on a nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel, which was then dried and autoradiographed.

DNA helicase and ATPase assays.

The DNA helicase substrate, which consisted of a radiolabeled 26-mer annealed to single-stranded M13 DNA, was prepared as described previously (17). The helicase assays were performed under the conditions developed by Im and Muzyczka (17) with modifications described by Kyöstiö and Owens (26). Briefly, 32P-labeled helicase substrate (25,000 cpm) was incubated with 2 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ or a mutant protein in a 30-μl reaction volume containing 25 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2% glycerol, 0.2 μg of BSA, and 0.4 mM ATP. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 35 min at 24°C, the reactions were terminated by the addition of 15 μl of gel loading buffer (0.5% SDS, 50 mM EDTA, 40% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 0.1% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol), and the reaction products were resolved on a nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA). The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography. ATPase assays were carried out according to the procedure described by Warrener et al. (61), with modifications as described by Wonderling et al. (65).

In vitro translation.

In vitro-translated Rep68 was synthesized with plasmid pMAT21 (38) and the TNT coupled T7-rabbit reticulocyte lysate, in vitro transcription-translation system in 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 20 μCi of 35S-labeled methionine as directed by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The correct size of the product was verified by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays were based on the method of Smith et al. (48). Recombinant protein G-agarose resin was washed and resuspended in binding buffer (0.01 M sodium phosphate [pH 7.0], 0.15 M NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) to form a 50% (vol/vol) slurry. 35S-labeled in vitro-translated Rep68 (7.5 μl) was diluted 25-fold with ice-cold binding buffer, and 0.5 M ATP was added to a final concentration of 5 mM. The diluted protein solution was precleared by adding 20 μl of protein G-agarose slurry and mixing by repeated inversion of the test tube at 4°C for 30 min. After a brief centrifugation, the cleared protein solution was transferred to a new tube and 0.9 μg of purified MBP-Rep68Δ, MBP-LacZ, or mutant MBP-Rep68Δ protein was added. The resulting solution was mixed by constant inversion of the test tube at 4°C for at least 1 h. Next, 2 μl of rabbit polyclonal anti-MBP serum (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) was added and the solution was mixed by inversion for 2 h at 4°C. Following this incubation, 40 μl of protein G-agarose slurry was added and the mixture was incubated a final time with inversion for 1 h at 4°C. Following this final incubation, the protein G-agarose beads were sedimented by centrifugation and washed four times with 5 volumes of 4°C binding buffer to remove unbound proteins. After the final wash the protein G-agarose beads and associated proteins were pelleted by brief centrifugation. The complexed proteins were then eluted by boiling the pellets for 5 min in 2 bed volumes of 1× sample buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.0025% bromophenol blue). Eluted proteins were resolved by SDS–10% PAGE, fixed in 20% acetic acid–10% methanol–5% glycerol, soaked in Enlightning autoradiography enhancer (New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.) and visualized by fluorography. The bands of radiolabeled Rep68 were also excised and counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

RESULTS

We set out to identify regions within Rep68 which are important for protein-DNA and protein-protein interaction. To achieve this goal we replaced the lysine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid residues within areas of high local charge density (three charged amino acid residues within a stretch of five) with alanines, based on the assumption that these areas of high localized charge density are more likely to exist on the surface of the protein and are therefore likely to participate in intermolecular association (Fig. 1).

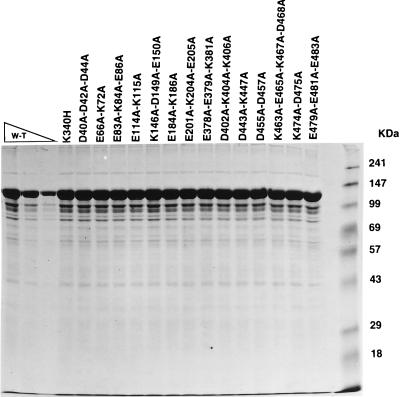

Purification of wild-type and mutant MBP-Rep68Δ proteins.

Wild-type and mutant recombinant MBP-Rep68Δ proteins were expressed in E. coli cells. Mutant proteins were purified from the crude sonicates by selective retention on amylose resin as described previously (10, 65). The eluted fractions were analyzed and the predicted molecular mass of 105 kDa was confirmed for the predominant protein species by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2). The levels of purification varied slightly from preparation to preparation; however, all mutant proteins were obtained as stable proteins which were immunoreactive to Rep68-specific antisera on Western blots (data not shown) and were in concentrations suitable for assessment by in vitro assays. The results of our in vitro analyses are summarized in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified E. coli-expressed MBP-fusion proteins. Ten, 5, and 2.5 μg of wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ (W-T) and 10 μg of other MBP fusion proteins (indicated above the gel) were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular mass markers are indicated in kilodaltons.

TABLE 2.

Summary of MBP-Rep68Δ mutant proteins and their activities

| MBP fusion protein or mutation(s) | Activitya

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV hairpin DNA binding | trs endo-nuclease | DNA helicase | Rep-Rep association | Negative dominance

|

||

| trs endonuclease | DNA helicase | |||||

| Rep68Δ (wild type) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | NT | NT |

| K340H | ++ | − | − | ++ | Yes | Yes |

| D40A-D42A-D44A | − | − | + | ± | No | NT |

| E66A-K72A | + | ± | + | + | NT | NT |

| E83A-K84A-E86A | ± | − | ++ | + | No | NT |

| E114A-K115A | + | ± | + | + | NT | NT |

| K146A-D149A-E150A | + | − | ++ | ± | No | NT |

| E184A-K186A | + | + | + | + | NT | NT |

| E201A-K204A-E205A | ++ | + | ++ | + | NT | NT |

| E378A-E379A-K381A | ±b | − | − | ± | No | No |

| D402A-K404A-K406A | ++ | − | − | ++ | Yes | Yes |

| D443A-K447A | ±b | − | − | ± | No | No |

| D455A-D457A | + | − | − | ± | No | No |

| K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A | ± | − | − | ± | No | No |

| K474A-D475A | ± | − | − | ± | NT | NT |

| E479A-E481A-E483A | + | − | − | ± | No | No |

++, at or near wild-type activity; +, activity greater than one-fourth but clearly less than that of the wild type; ±, activity less than one-fourth of that of the wild type but clearly above background; −, no detectable activity; NT, not tested; Yes, activity of the wild-type protein was reduced by greater than 50%; No, no apparent reduction in the activity of the wild-type protein.

Abnormal shifted band pattern.

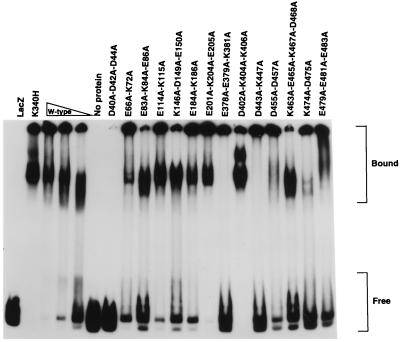

Binding of wild-type and charge-to-alanine mutant MBP-Rep68Δ proteins to AAV hairpin DNA.

To determine if any of the charge neutralization mutations affected binding to AAV hairpin DNA, the mutant proteins were analyzed by an EMSA in which MBP-Rep68Δ (wild-type) and MBP-Rep68Δ-K340H proteins were used as positive controls for binding to the hairpin substrate. It has been well established that Rep proteins with the K340H mutation lack trs endonuclease, helicase, and ATPase activities but have the ability to bind AAV hairpin DNA at levels comparable to that bound by wild-type Rep68 (26, 37, 38, 59, 68). As seen in Fig. 3, the EMSA results are quite complex. There are qualitative, as well as quantitative, differences in the levels of hairpin DNA binding of the mutants relative to those of the K340H mutant and wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ proteins. Both the wild-type and K340H proteins produce two classes of protein-DNA complexes. The first class migrates part of the way through the gel, and the second class remains at the top of the gel, in the wells. Previous EMSAs with wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ have shown that both classes of complexes can be competed away specifically with unlabeled DNA containing a Rep recognition sequence (67). Due to the heterogeneous nature of the shifted bands, we had to judge the relative binding activities by comparing the amount of unbound DNA with each mutant protein to those in the dilution series of the wild-type protein. Of the new mutant proteins tested here, only the E201A-K204A-E205A and D402A-K404A-K406A proteins were similar to the wild-type in the amount of hairpin DNA bound per microgram of protein. The E66A-K72A, E114A-K115A, K146A-D149A-E150A, E184A-K186A, D455A-D457A, and E479A-E481A-E483A proteins had binding activities equivalent to between one-half and one-quarter of the activity of the wild-type protein. Two micrograms of the E83A-K84A-E86A, K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A, or K474A-D475A mutant protein bound less hairpin DNA than 0.5 μg of the wild-type protein but still retained a somewhat normal pattern of shifted bands. Two micrograms of the E378A-E379A-K381A or D443A-K447A mutant protein bound less hairpin DNA than 0.5 μg of the wild-type protein and lacked clearly discernible bands that migrated part of the way through the gel. With the E378A-E379A-K381A and D443A-K447A proteins all of the shifted DNA was retained in the wells. Only the D40A-D42A-D44A mutant protein was completely incapable of binding hairpin DNA.

FIG. 3.

EMSA of purified wild-type (W-type) and mutant MBP-Rep68Δ proteins with AAV hairpin DNA. Each sample contained 5,000 cpm of AAV terminal repeat hairpin DNA labeled at its 5′ end with 32P. The positions of free and bound DNAs are indicated at the right. Reaction mixtures contained either no protein; 2.0, 1.0, or 0.5 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ; or 2.0 μg of MBP-LacZ (LacZ) or the fusion protein containing the indicated mutation. The proteins were incubated in the standard binding reaction mixture at 24°C for 30 min and electrophoresed in a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel. Wild-type Rep68 does not bind double-stranded DNA without a Rep recognition sequence under these conditions (63).

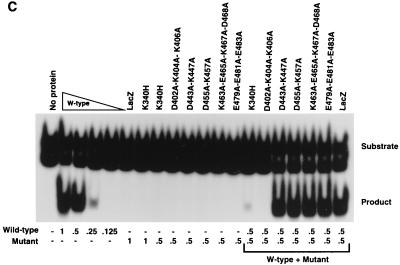

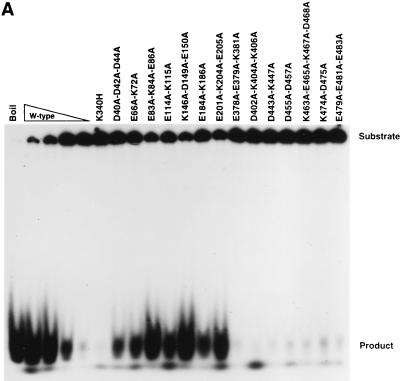

The effect of charge-to-alanine mutations on MBP-Rep68Δ trs endonuclease (nicking) activity.

The MBP-Rep68Δ charge-to-alanine mutant proteins were assessed for their ability to cleave AAV hairpin DNA labeled with 32P at its 5′ end in the trs endonuclease assay. The E184A-K186A and E201A-K204A-E205A mutant proteins displayed trs endonuclease activities equivalent to between one-half and one-quarter of the activity of wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ (Fig. 4A). The E66A-K72A and E114A-K115A proteins had low, but detectable, levels of endonuclease activity. All other mutant proteins lacked detectable nicking activity (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

trs endonuclease assays of wild-type and mutant MBP-Rep68Δ fusion proteins. trs endonuclease assays were performed (as detailed in Materials and Methods) with mutant fusion proteins whose mutations are indicated above each lane. Each sample contained 25,000 cpm of AAV terminal repeat hairpin DNA labeled at its 5′ end with 32P. All reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 60 min, briefly heated to 100°C, and resolved on a nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. The positions of the substrate and released cleavage product are indicated at the right. (A) Effects of site-specific mutations on the ability to cleave AAV hairpin DNA. Samples contained either no protein or 2.0 μg of the MBP fusion protein whose mutations are indicated above the respective lane, except for the wild-type (W-type) lanes, which contained 2.0, 1.0, 0.5, or 0.25 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ. (B and C) Analysis of negative dominance of endonuclease-negative mutants. Samples contained either no protein or the amount of each protein (in micrograms) indicated below each lane.

The trs endonuclease-negative mutant proteins were tested for negative dominance. The mutant proteins were mixed with wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ in a 1:1 ratio, and the degree of endonuclease inhibition was determined. The dominant-negative K340H mutant protein, which inhibits the endonuclease activity of wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ (10), was used as a control (Fig. 4B and C). As seen in Fig. 4B and C, only the D402A-K404A-K406A protein was capable of fully inhibiting wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease activity. The other mutant proteins which were negative for endonuclease activity were unable to significantly inhibit wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ endonuclease activity when they were mixed in the in vitro reaction mixture.

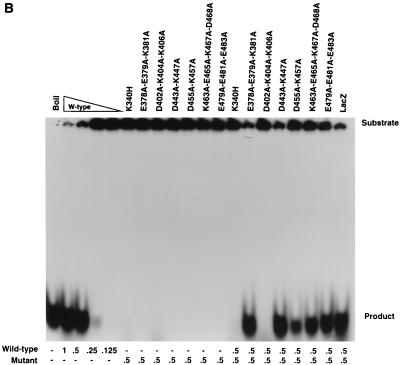

The effects of charge-to-alanine mutations on MBP-Rep68Δ DNA helicase activity.

The MBP-Rep68Δ mutant proteins were assayed for their ability to unwind a labeled 26-base oligonucleotide from an M13 DNA circle (Fig. 5A). Two micrograms of any of the amino-terminal mutant proteins (the D40A-D42A-D44A, E66A-K72A, E83A-K84A-E86A, E114A-K115A, K146A-D149A-E150A, E184A-K186A, and E201A-K204A-E205A proteins) retained the ability to unwind the labeled DNA helicase substrate at least as well as 0.5 μg of the wild type (Fig. 5A). The D40A-D42A-D44A, E66A-K72A, E114A-K115A, and E184A-K186A mutant proteins did, however, have clearly lower activities than wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ. No significant helicase activity was observed for the carboxyl-terminal-mutation proteins (the E378A-E379A-K381A, D402A-K404A-K406A, D443A-K447A, D455A-D457A, K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A, K474A-D475A, and E479A-E481A-E483A proteins) (Fig. 5A). It should be noted that all of the helicase-negative mutants were also trs endonuclease negative.

FIG. 5.

DNA helicase assays of purified wild-type and mutant MBP fusion proteins. Helicase assays were performed (as detailed in Materials and Methods) with the mutant fusion proteins whose mutations are indicated above each lane. The positions of the substrate and the product are indicated at the right. All reaction mixtures were incubated at 24°C for 35 min and resolved on a nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. The reaction mixtures in the lanes marked “Boil” were heated to 100°C for 5 min prior to being loaded. (A) Effects of site-specific substitutions on helicase activity. Reaction mixtures contained either no protein; 2, 1, 0.5, or 0.25 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ (W-type); or 2 μg of one of the mutant proteins whose mutations are indicated. (B) Analysis of negative dominance of helicase-negative proteins. The amounts (in micrograms) of mutant and/or wild-type protein in the reaction mixtures are indicated below the lanes.

The helicase-negative mutant proteins, including that with the K340H mutation, which had previously demonstrated negative dominance (59, 65), were also assayed for negative dominance in the DNA helicase assay. The D402A-K404A-K406A and K340H mutant proteins were the only proteins tested which were able to significantly inhibit wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ helicase activity (Fig. 5B).

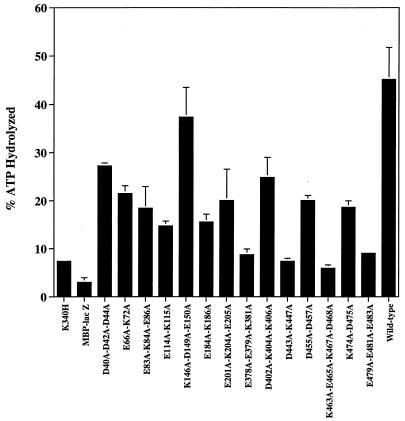

The effects of charge-to-alanine mutations on MBP-Rep68Δ ATPase activity.

Figure 6 shows the results of our ATPase assays. Due to variation in the background levels of E. coli ATPases contaminating our MBP fusion proteins, it was very difficult to distinguish between mutant proteins with less than one-fourth of the ATPase activities of wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ and mutant proteins with no ATPase activity. We are, however, fairly certain that under the conditions used all mutant proteins which showed greater than 10% hydrolysis of ATP (the D40A-D42A-D44A, E66A-K72A, E83A-K84A-E86A, E114A-K115A, K146A-D149A-E150A, E184A-K186A, E201A-K204A-E205A, D402A-K404A-K406A, D455A-D457A, and K474A-D475A proteins) are truly ATPase positive to some degree. Note that all of these ATPase-positive proteins are also helicase positive, except for the D402A-K404A-K406A, D455A-D457A, and K474A-D475A mutant proteins, whose samples showed ATPase levels higher than those of the helicase-positive E114A-K115A and E184A-K186A proteins. All mutant proteins whose ATPase levels were below this 10% cutoff (K340H, E378A-E379A-K381A, D443A-K447A, K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A, and E479A-E481A-E483A proteins) are helicase negative.

FIG. 6.

ATPase assays of purified wild-type and mutant MBP fusion proteins. In a final volume of 10 μl, 2 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ protein was incubated in a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μg of single-stranded M13mp18 DNA, and 3.33 fmol of [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 24°C for 1 h, the reaction was terminated by the addition of EDTA (20 mM, final concentration), and the reaction products were fractionated by thin-layer chromatography. One microliter of the reaction mixture was spotted onto a plastic-backed polyethyleneimine-cellulose sheet (EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J.) and developed by ascending-solvent chromatography in 0.375 M potassium phosphate (pH 3.5). The sheets were dried and autoradiographed. The spots containing the radioactive substrate and product were excised, and the radioactivity was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting. Each column represents the mean of results from three trials. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

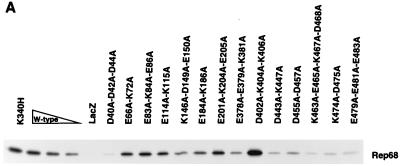

The interactions of charge-to-alanine mutant MBP-Rep68Δ proteins with radiolabeled wild-type Rep68 protein in vitro.

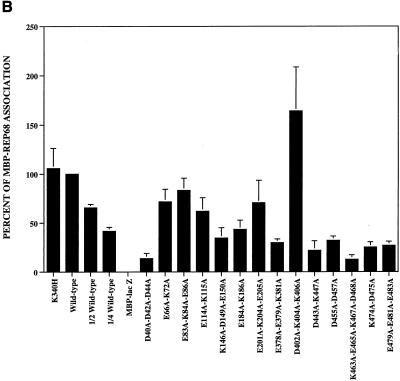

We tested the abilities of our charge-to-alanine mutant proteins to associate with radiolabeled wild-type Rep68 protein in coimmunoprecipitation assays. These assays were performed in the presence of ATP, which is believed to stimulate oligomerization of Rep proteins (28, 48). As expected, MBP-LacZ had no detectable association with the radiolabeled Rep68 protein. Wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ and the MBP-Rep68Δ-K340H protein were included as positive controls. All of the mutant proteins displayed an ability to interact with 35S-labeled Rep68 to some degree (Fig. 7). Mutations in the amino-terminal region of the Rep68 moiety of MBP-Rep68Δ generally had less-detrimental effects on the association with 35S-labeled Rep68 than mutations in the carboxyl-terminal region, with the exception of the mutations of the DNA-binding-deficient D40A-D42A-D44A protein (Fig. 7). The K146A-D149A-E150A and the E184A-K186A mutant proteins also had significantly less association with Rep68 than wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ. The carboxyl-terminal mutant proteins, i.e., the E378A-E379A-K381A, D443A-K447A, D455A-D457A, K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A, K474A-D475A, and E479A-E481A-E483A proteins, all displayed a weakened association with the wild-type protein. One notable exception among the proteins with carboxyl-terminal mutations was the dominant-negative D402A-K404A-K406A mutant protein (Table 2), which apparently associated with labeled Rep68 better than the wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ protein.

FIG. 7.

Association of 35S-labeled in vitro-translated Rep68 protein with purified E. coli-expressed MBP-Rep68Δ polypeptides. Samples contained 2.0 μg of an MBP fusion protein (mutations are indicated above each lane), except for the wild-type (W-type) lanes which contained 2.0, 1.0, and 0.5 μg of MBP-Rep68Δ. Proteins were tested for their ability to associate with radiolabeled Rep68 as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Coimmunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS–10% PAGE and visualized by fluorography. (B) Comparison of the quantity of radioactivity coimmunoprecipitated by 2.0 μg of a mutant protein (mutations are indicated below the bars) with that coimmunoprecipitated by 2.0 μg of the MBP-Rep68Δ standard (wild type), arbitrarily set at 100%. The bars labeled “1/2 wild-type” and “1/4 wild-type” represent samples which contained 1 and 0.5 μg, respectively, of MBP-Rep68Δ. The error bars represent 1 standard deviation for results from at least three trials.

DISCUSSION

There were two goals to this study. The first was to identify the residues required for specific DNA binding. The second goal was to identify residues involved in Rep-Rep interactions. We adopted the strategy of alanine scanning mutagenesis to introduce mutations within areas of high localized charge density (likely to be at the surface of the protein) throughout the Rep moiety of the MBP-Rep68Δ fusion protein. These mutant proteins were tested for AAV hairpin DNA binding and helicase and trs endonuclease activities, as well as their ability to associate with wild-type Rep68 in vitro. The results of these experiments are summarized in Table 2.

Several observations imply that an amino-terminal domain in Rep68/78 is responsible for specific AAV hairpin binding. Rep52 and Rep40, both of which are nonstructural proteins of AAV that lack the amino-terminal 224 amino acids found in Rep68/78 but contain amino acids 225 through 529, have been shown to be incapable of specifically binding AAV hairpin DNA (19). Deletion of the carboxyl-terminal regions of Rep78 to glutamine 241, with the addition of a positively charged missense tail, resulted in a protein capable of specifically binding AAV hairpin DNA, albeit weakly (38). In addition, several deletion, insertion, truncation, and site-specific mutations within the amino-terminal region which abolish DNA binding have been reported (3, 33, 59, 62, 70). In the study presented here the D40A-D42A-D44A mutant protein further defines the importance of the amino-terminal domain for specific DNA binding. Yang and Trempe (70) previously demonstrated that the deletion of amino acids 25 to 56 abolishes hairpin binding. Our D40A-D42A-D44A mutant protein also had no detectable AAV hairpin binding (Fig. 3). Since this mutant protein retained the ability to hydrolyze ATP (Fig. 6) and had detectable helicase activity (Fig. 5), its inability to bind hairpin DNA is not simply the result of a global disruption of protein conformation.

The fact that the D40A-D42A-D44A mutant protein had no detectable AAV hairpin binding ability and yet was capable of unwinding the helicase substrate approximately one-fourth as well as wild-type MBP-Rep68Δ suggests that the domain for AAV hairpin-specific binding must be separable from the proposed nonspecific, single-stranded DNA binding domain, which is thought to be necessary for helicase activity (19, 32). Rep protein sequences with homology to other helicase and ATPase proteins are located between Rep68/78 amino acids 329 and 422 (22). An MBP-Rep52 fusion protein, which lacks the amino-terminal 224 amino acids of Rep68/78, is also helicase positive (47).

In this study, only the D40A-D42A-D44A mutation completely disrupted hairpin DNA binding. The fact that mutation of many of the other charged (and presumably surface) amino acids resulted in a significant, although less dramatic, decrease in hairpin binding suggests that there may be multiple contacts between Rep68/78 and AAV hairpin DNA. Consistent with this model, modification of bases covering a 16- to 18-base region on either strand of the A-stem of AAV hairpin DNA interfered with Rep68/78 binding (38, 39). There is also a secondary Rep68/78 binding site in the B-C portion of the hairpin (39). It is also possible that some of these mutations disrupt protein-protein interaction domains which are required for hairpin DNA binding. Our data suggest that the oligomerization interface is also multipartite (Fig. 1 and 7).

Hydrophobic residues may also contribute to hairpin DNA binding. Walker et al. (59) have shown that mutation of tyrosine 224 to phenylalanine greatly reduces the ability of the protein to bind AAV hairpin DNA.

Two proteins, the E83A-K84A-E86A and K146A-D149A-E150A proteins, were negative for trs endonuclease activity and yet had significant hairpin DNA binding and helicase activities. Both retained association (albeit weaker than that of the wild type) in coimmunoprecipitation assays. Because these mutant proteins retained all functional activities other than nicking, their charged regions (E83-K84-E86 and K146-D149-E150) may be involved in the active site for endonuclease activity. In fact, mutation of tyrosine 152 to a phenylalanine also results in an endonuclease-negative, DNA-binding-positive, helicase-positive protein (59).

The D402A-K404A-K406A and K340H mutant proteins were the only ones tested which displayed the dominant-negative phenotype for both nicking and helicase. These mutants, as expected, displayed a strong association with radiolabeled wild-type Rep68 in coimmunoprecipitation assays. These mutated residues are highly conserved within parvovirus nonstructural proteins (60) and reside within the B′ and A motifs, respectively, of the putative helicase domain (22). Additionally, the K340H mutation is in the P-loop of a well-characterized nucleoside triphosphate association domain (41, 43) and this mutation is known to abolish ATPase activity (65). Mutation of the B′ domain at amino acid 404 by McCarty et al. (33) (K404I, K404T) and Walker et al. (60) (K404A) resulted in mutant proteins which bound hairpin DNA in vitro and retained ATPase activity (60) but lacked both nicking (33, 60) and helicase (60) activities. Our D402A-K404A-K406A mutant protein likewise lacked nicking and helicase activities and hydrolyzed ATP (Fig. 6; Table 2). The fact that this mutant protein retained the ability to hydrolyze ATP distinguishes it from the K340H mutant protein. Interestingly, the D402A-K404A-K406A protein is the only ATPase-positive, dominant-negative, helicase-negative Rep mutant protein reported in the literature to date. Although the Rep68/78 helicase activity is thought to require ATPase activity (32, 65), the results with this mutant protein suggest that helicase activity can be abolished in wild-type–mutant protein hetero-oligomers by a mechanism that is not dependent upon abolishing ATPase activity.

Charge cluster mutations in the region from amino acids 378 to 483 resulted in mutant proteins which retained at least some ability to bind to AAV hairpin DNA. However, all of the proteins with mutations in this region of the molecule lacked both endonuclease and helicase activity, in spite of the fact that the D402A-K404A-K406A, D455A-D457A, and K474A-D475A mutant proteins retained ATPase activity which was clearly above background levels (Fig. 6). However, two mutant proteins, the E378A-E379A-K381A and D443A-K447A proteins, have very low levels of hairpin DNA binding in addition to lacking endonuclease, helicase, and ATPase activities (Table 2 and Fig. 6) and may therefore represent misfolded proteins. The relatively high charge density in the region from amino acids 378 to 483, as noted by the proximity of the mutations in the region (Fig. 1), does, however, suggest that these mutations may disrupt a local structural entity required for both the endonuclease and helicase activities of the Rep proteins.

Several other mutation studies also illustrated the importance of this region for Rep68/78 function (33, 60, 62, 69, 70). Many insertions, deletions, or amino acid substitutions in the region from amino acids 378 to 483 abolished helicase and/or nicking activities of Rep68/78 in vitro (33, 59, 60, 62) or the ability of Rep68/78 to complement replication of rep mutant AAV in vivo (33, 69). Some of these mutations even disrupted hairpin DNA binding (33, 62, 70), indicating that this region may be involved in the stabilization of sequence-specific binding of Rep proteins to double-stranded DNA.

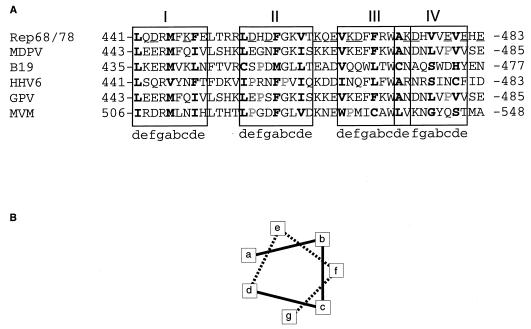

Because the nicking and helicase functions are believed to be mediated through oligomers of Rep proteins, we believe that the lack of nicking and helicase activities for most of the charge cluster mutant proteins with mutations in the region from amino acids 378 to 483 is attributable to a loss of the ability of these charge cluster mutant proteins to form functional oligomers. Consistent with this hypothesis, Weitzman et al. (62) showed by EMSA analysis that although a Rep truncation containing the first 476 amino acids of Rep68/78 appeared to form oligomers efficiently with wild-type Rep68 on AAV hairpin DNA, a mutant protein containing the first 466 amino acids formed mixed complexes less efficiently and those complexes were qualitatively different from those formed by the mutant protein containing amino acids 1 to 476. Smith et al. (48) using the same coimmunoprecipitation assay that we used, showed that MBP-Rep78 efficiently bound 35S-labeled mutant proteins containing Rep68/78 amino acids 1 to 484 but not one containing amino acids 1 to 371. We have also identified a series of discontinuous 3,4 hydrophobic heptad repeats (11, 12) in Rep68/78 which span amino acids 441 to 481 (Fig. 8). This repeated motif is also conserved in the nonstructural (replication) proteins of muscovy duck parvovirus (MDPV) (71), human erythrovirus B19 (B19) (45), goose parvovirus (GPV) (71), and minute virus of mice (MVM) (2) (Fig. 8), as well as the human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) Rep homolog (54). The 3,4 hydrophobic heptad repeat motif has been well characterized for other eukaryotic proteins containing coiled-coil domains such as the basic leucine zipper class of mammalian transcription factors, which includes C/EBP, Fos, and Jun (58, 64). These coiled-coil domains are involved in protein recognition as well as oligomerization (58). The hydrophobic residues at positions a and d in Fig. 8B in the Rep68/78 motif may represent a repeating helical dimerization interface. Charged residues at positions e and g (Fig. 8) are thought to stabilize oligomerization by forming interhelical salt bridges (11). We predict that our charge-to-alanine mutations (many of which are at position e or g) in the suspected coiled-coil domain in MBP-Rep68Δ disrupt the formation of interhelical salt bridges between subunits in mutant complexes, thereby inhibiting the stability and/or proper formation of oligomers required for efficient nicking and helicase activities. This prediction is supported by the weakened association between MBP-Rep proteins containing charge mutations within this predicted motif (D443A-K447A, D455A-D457A, K463A-E465A-K467A-D468A, K474A-D475A, and E479A-E481A-E483A) and wild-type Rep68 in our coimmunoprecipitation assays. Upon closer comparison of this series of putative heptad repeats (denoted I through IV in Fig. 8) with those of other parvovirus replication proteins, we found proline residues which were not present in Rep68/78 proteins. These proline residues appear to be concentrated in heptad repeat II of the Rep homologs (B19, HHV6, GPV, and MVM) and heptad repeat IV of the avian Rep homologs (MDPV and GPV); proline 532 of heptad repeat III in MVM represents the only exception. Considering the helical destabilizing effect of proline residues, it is likely that the secondary structures of heptads II and IV, and in one case of heptad III, may not be preserved in the Rep homologs of these other viruses. The disruption of certain areas of this repeating motif in these Rep homologs may imply a functional redundancy for parts of this repeating motif in the Rep68 molecule.

FIG. 8.

(A) Amino acid sequence alignments comparing the region surrounding the putative 3,4-heptad repeat (possible coiled-coil) region in Rep68/78 with similar regions in other parvovirus replication proteins and the Rep homolog encoded by HHV6. Sequences shown are of proteins from MDPV (71), B19 (45), HHV6 (54), GPV (71), and MVM (2). The sequences were aligned with the aid of the BestFit local alignment program (49). The alignments shown are the relevant portions of the predicted heptad repeat structure in the Rep68/78 proteins. The bold letters represent the conserved hydrophobic amino acids. Charged residues which were converted to alanine in mutants are underlined. Prolines are shown with outlined letters. The heptad repeat unit is indicated by lowercase letters (a to g). Residues at the a and d positions of the heptad repeat unit form the hydrophobic interface, while those at positions e and g participate in the formation of stabilizing salt bridges (11) and the specificity of helical interaction (58). Putative heptad repeat units for each protein are boxed and denoted I to IV. (B) Schematic of the relative positions of the amino acids with respect to the central axis of the putative helix (42).

Although it is clear that this putative coiled-coil domain that we have tentatively characterized is important for nicking and helicase activity in vitro, our results, as well as those of others, demonstrate that it is not the only domain required for optimal Rep protein self-association. Smith et al. demonstrated that deletion of amino acids 151 to 188 and/or 334 to 347, which contain another putative coiled-coil region and part of the A motif of the conserved ATPase and helicase domain of Rep68/78, respectively, also greatly reduced Rep protein self-association in vitro (48). However, they did not report on the status of their mutants in either nicking, helicase, or replication assays. Walker et al. demonstrated that conservative point mutations in this same A region of the ATPase-helicase domain (G334A, G339A, and T341A) of Rep68 resulted in mutant proteins which lacked nicking and helicase activities (60). It is not surprising that there is a Rep-Rep interaction subdomain within the ATPase-helicase domain since nearly all helicases studied to date function as multimers (32) and this is the primary region of homology between members of this family of helicases (22). Our results with the protein containing the E378A-E379A-K381A mutation, which overlaps ATPase-helicase motif B and is found outside of our putative coiled-coil region in another area of the predicted alpha-helical structure, are consistent with this hypothesis. This mutant protein lacks both helicase and endonuclease activity and associates weakly with wild-type Rep68 in coimmunoprecipitation assays. In conclusion, it appears that several sites of protein-protein association are present in Rep68/78 and that they all may influence Rep activities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nancy Nossal and John Hanover for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Jan Schwartz and Robert Kotin for useful communications.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoni B A, Rabson A B, Miller I L, Trempe J P, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus Rep protein inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 production in human cells. J Virol. 1991;65:396–404. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.396-404.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astell C R, Gardiner E M, Tattersall P. DNA sequence of the lymphotropic variant of minute virus of mice, MVM(i), and comparison with the DNA sequence of the fibrotropic prototype strain. J Virol. 1986;57:656–669. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.656-669.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batchu R B, Hermonat P L. Disassociation of conventional DNA binding and endonuclease activities by an adeno-associated virus Rep78 mutant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:717–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaton A, Palumbo P, Berns K I. Expression from the adeno-associated virus p5 and p19 promoters is negatively regulated in trans by the rep protein. J Virol. 1989;63:4450–4454. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4450-4454.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bordo D, Argos P. Suggestions for “safe” residue substitutions in site-directed mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:721–729. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90528-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brendel V, Karlin S. Association of charge clusters with functional domains of cellular transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5698–5702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus helper functions. In: Tijssen P, editor. Handbook of parvoviruses. I. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 255–282. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter B J, Mendelson E, Trempe J P. AAV DNA replication, integration, and genetics. In: Tijssen P, editor. Handbook of parvoviruses. I. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 169–226. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Replication of a human parvovirus nonsense mutant in mammalian cells containing an inducible amber suppressor. Virology. 1989;171:239–247. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiorini J A, Weitzman M D, Owens R A, Urcelay E, Safer B, Kotin R M. Biologically active Rep proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 produced as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1994;68:797–804. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.797-804.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen C, Parry D A D. α-Helical coiled coils and bundles: how to design an α-helical protein. Proteins. 1990;7:1–15. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen C, Parry D A D. α-Helical coiled coils—a widespread motif in proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1986;11:245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus is directed by a cellular DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10039–10043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauswirth W W, Berns K I. Origin and termination of adeno-associated virus DNA replication. Virology. 1977;78:488–499. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermonat P L. Down-regulation of the human c-fos and c-myc proto-oncogene promoters by adeno-associated virus Rep78. Cancer Lett. 1994;81:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Im D S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Im D S, Muzyczka N. Factors that bind to adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1989;63:3095–3104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3095-3104.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Im D S, Muzyczka N. Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J Virol. 1992;66:1119–1128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1119-1128.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlin S, Brendel V. Charge configurations in oncogene products and transforming proteins. Oncogene. 1990;5:85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlin S, Brendel V. Charge configurations in viral proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9396–9400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koonin E V. A common set of conserved motifs in a vast variety of putative nucleic acid-dependent ATPases including MCM proteins involved in the initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2541–2547. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.11.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotin R M, Linden R M, Berns K I. Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous recombination. EMBO J. 1992;11:5071–5078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotin R M, Menninger J C, Ward D C, Berns K I. Mapping and direct visualization of a region-specific viral DNA integration site on chromosome 19q13-qter. Genomics. 1991;10:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotin R M, Siniscalco M, Samulski R J, Zhu X, Hunter L, Laughlin C A, McLaughlin S, Muzyczka N, Rocchi M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2211–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A. Identification of mutant adeno-associated virus Rep proteins which are dominant-negative for DNA helicase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:294–299. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Antoni B A, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Analysis of adeno-associated virus (AAV) wild-type and mutant Rep proteins for their abilities to negatively regulate AAV p5 and p19 mRNA levels. J Virol. 1994;68:2947–2957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2947-2957.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyöstiö S R M, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Negative regulation of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) P5 promoter involves both the P5 Rep binding site and the consensus ATP-binding motif of the AAV Rep68 protein. J Virol. 1995;69:6787–6796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6787-6796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labow M A, Graf L H, Jr, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus gene expression inhibits cellular transformation by heterologous genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1320–1325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labow M A, Hermonat P L, Berns K I. Positive and negative autoregulation of the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome. J Virol. 1986;60:251–258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.251-258.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matson S W, Kaiser-Rodgers K A. DNA helicases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:289–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarty D M, Ni T H, Muzyczka N. Analysis of mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep protein in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:4050–4057. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4050-4057.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarty D M, Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Zhou X, Muzyczka N. Interaction of the adeno-associated virus Rep protein with a sequence within the A palindrome of the viral terminal repeat. J Virol. 1994;68:4998–5006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4998-5006.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendelson E, Trempe J P, Carter B J. Identification of the trans-acting Rep proteins of adeno-associated virus by antibodies to a synthetic oligopeptide. J Virol. 1986;60:823–832. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.823-832.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owens R A, Carter B J. In vitro resolution of adeno-associated virus DNA hairpin termini by wild-type Rep protein is inhibited by a dominant-negative mutant of Rep. J Virol. 1992;66:1236–1240. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1236-1240.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owens R A, Trempe J P, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins produced in insect and mammalian expression systems: wild-type and dominant-negative mutant proteins bind to the viral replication origin. Virology. 1991;184:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90817-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Carter B J. Identification of a DNA-binding domain in the amino terminus of adeno-associated virus Rep proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:997–1005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.997-1005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1996;70:1542–1553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1542-1553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samulski R J, Srivastava A, Berns K I, Muzyczka N. Rescue of adeno-associated virus from recombinant plasmids: gene correction within the terminal repeats of AAV. Cell. 1983;33:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saraste M, Sibbald P R, Wittinghofer A. The P-loop—a common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiffer M, Edmundson A B. Use of helical wheels to represent the structures of proteins and to identify segments with helical potential. Biophys J. 1967;7:121–135. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(67)86579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz G E. Binding of nucleotides by proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1992;2:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senapathy P, Tratschin J D, Carter B J. Replication of adeno-associated virus DNA. Complementation of naturally occurring rep− mutants by a wild-type genome or an ori− mutant and correction of terminal palindrome deletions. J Mol Biol. 1984;179:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shade R O, Blundell M C, Cotmore S F, Tattersall P, Astell C R. Nucleotide sequence and genome organization of human parvovirus B19 isolated from the serum of a child during aplastic crisis. J Virol. 1986;58:921–936. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.3.921-936.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shelling A N, Smith M G. Targeted integration of transfected and infected adeno-associated virus vectors containing the neomycin resistance gene. Gene Ther. 1994;1:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith R H, Kotin R M. The Rep52 gene product of adeno-associated virus is a DNA helicase with 3′-to 5′ polarity. J Virol. 1998;72:4874–4881. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4874-4881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith R H, Spano A J, Kotin R M. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4461-4471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith T F, Waterman M S. Comparison of biosequences. Adv Appl Math. 1981;2:482–489. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snyder R O, Im D S, Muzyczka N. Evidence for covalent attachment of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein to the ends of the AAV genome. J Virol. 1990;64:6204–6213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6204-6213.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snyder R O, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. In vitro resolution of covalently joined AAV chromosome ends. Cell. 1990;60:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90720-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srivastava A, Lusby E W, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Straus S E, Sebring E D, Rose J A. Concatemers of alternating plus and minus strands are intermediates in adenovirus-associated virus DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:742–746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomson B J, Efstathiou S, Honess R W. Acquisition of the human adeno-associated virus type-2 rep gene by human herpesvirus type-6. Nature (London) 1991;351:78–80. doi: 10.1038/351078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tratschin J D, Tal J, Carter B J. Negative and positive regulation in trans of gene expression from adeno-associated virus vectors in mammalian cells by a viral rep gene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2884–2894. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trempe J P, Mendelson E, Carter B J. Characterization of adeno-associated virus rep proteins in human cells by antibodies raised against rep expressed in Escherichia coli. Virology. 1987;161:18–28. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urcelay E, Ward P, Wiener S M, Safer B, Kotin R M. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2038–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2038-2046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vinson C R, Hai T, Boyd S M. Dimerization specificity of the leucine zipper-containing bZIP motif on DNA binding: prediction and rational design. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1047–1058. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker S L, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein: identification of critical residues necessary for site-specific endonuclease activity. J Virol. 1997;71:2722–2730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2722-2730.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walker S L, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep68 protein helicase motifs. J Virol. 1997;71:6996–7004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6996-7004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warrener P, Tamura J K, Collett M S. RNA-stimulated NTPase activity associated with yellow fever virus NS3 protein expressed in bacteria. J Virol. 1993;67:989–996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.989-996.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Carter B J, Owens R A. Interaction of wild-type and mutant adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins on AAV hairpin DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2440–2448. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2440-2448.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams S C, Cantwell C A, Johnson P F. A family of C/EBP-related proteins capable of forming covalently linked leucine zipper dimers in vitro. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1553–1567. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wonderling R S, Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A. A maltose-binding protein/adeno-associated virus Rep68 fusion protein has DNA-RNA helicase and ATPase activities. J Virol. 1995;69:3542–3548. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3542-3548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wonderling R S, Kyöstiö S R M, Walker S L, Owens R A. The Rep68 protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 increases RNA levels from the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early promoter. Virology. 1997;236:167–176. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Binding sites for adeno-associated virus Rep proteins within the human genome. J Virol. 1997;71:2528–2534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2528-2534.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wonderling R S, Owens R A. The Rep68 protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 stimulates expression of the platelet-derived growth factor B c-sis proto-oncogene. J Virol. 1996;70:4783–4786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4783-4786.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang Q, Kadam A, Trempe J P. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus rep gene. J Virol. 1992;66:6058–6069. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6058-6069.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang Q, Trempe J P. Analysis of the terminal repeat binding abilities of mutant adeno-associated virus replication proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:4442–4447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4442-4447.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zádori Z, Stefancsik R, Rauch T, Kisary J. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequences of goose and Muscovy duck parvoviruses indicates common ancestral origin with adeno-associated virus 2. Virology. 1995;212:562–573. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu Z Y, Karlin S. Clusters of charged residues in protein three-dimensional structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8350–8355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]