Key Points

Question

Is a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention during pregnancy effective in improving child neurodevelopment at age 2 years?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 626 children, Bayley-III scores were significantly higher in cognitive and social-emotional domains in the Mediterranean diet group and significantly higher in the social-emotional domain in the stress reduction group compared with the usual care group.

Meaning

Structured interventions during pregnancy based on a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction significantly improved child neurodevelopment at 2 years.

This prespecified analysis of a randomized clinical trial evaluates the effect of a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction during pregnancy on child neurodevelopment at age 2 years.

Abstract

Importance

Maternal suboptimal nutrition and high stress levels are associated with adverse fetal and childhood neurodevelopment.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that structured interventions based on a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) during pregnancy improve child neurodevelopment at age 2 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a prespecified analysis of the parallel-group Improving Mothers for a Better Prenatal Care Trial Barcelona (IMPACT BCN) randomized clinical trial, which was conducted at a university hospital in Barcelona, Spain, from February 2017 to March 2020. A total of 1221 singleton pregnancies (19 to 23 weeks’ gestation) with high risk of delivering newborns who were small for gestational age were randomly allocated into 3 groups: a Mediterranean diet intervention, an MBSR program, or usual care. A postnatal evaluation with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd Edition (Bayley-III), was performed. Data were analyzed from July to November 2022.

Interventions

Participants in the Mediterranean diet group received monthly individual and group educational sessions and free provision of extra virgin olive oil and walnuts. Those in the stress reduction group underwent an 8-week MBSR program adapted for pregnancy. Individuals in the usual care group received pregnancy care per institutional protocols.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Neurodevelopment in children was assessed by Bayley-III at 24 months of corrected postnatal age.

Results

A total of 626 children (293 [46.8%] female and 333 [53.2%] male) participated at a mean (SD) age of 24.8 (2.9) months. No differences were observed in the baseline characteristics between intervention groups. Compared with children from the usual care group, children in the Mediterranean diet group had higher scores in the cognitive domain (β, 5.02; 95% CI, 1.52-8.53; P = .005) and social-emotional domain (β, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.18-9.12; P = .01), whereas children from the stress reduction group had higher scores in the social-emotional domain (β, 4.75; 95% CI, 0.54-8.85; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this prespecified analysis of a randomized clinical trial, maternal structured lifestyle interventions during pregnancy based on a Mediterranean diet or MBSR significantly improved child neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03166332

Introduction

Prenatal well-being and health are strong determinants of future child and adult neurodevelopment.1,2,3 Maternal lifestyle is recognized as a potentially modifiable risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes and fetal neurodevelopment.4,5 Unhealthy high-fat dietary patterns and periconceptional obesity are associated with poorer neurodevelopment in the offspring.2,6,7 Likewise, increased maternal stress is associated with differences in fetal brain structure8,9 and poorer postnatal neurodevelopmental outcomes.3,9,10,11 The pathophysiological basis for these associations is poorly understood, but activation of inflammation and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis have been postulated as potential mechanisms.2,3,5 Interventions for improving nutritional patterns or reducing stress in adults have both been described to induce changes in inflammation and oxidation and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.12,13,14,15 However, to our knowledge, no randomized clinical trials have evaluated the effects of structured dietary or stress reduction lifestyle interventions during pregnancy on improving offspring neurodevelopment.

Concerning dietary interventions, previous studies have shown that the Mediterranean diet may reduce the incidence of health adverse outcomes, such as cardiovascular events, diabetes, cognitive declines, and other inflammatory-based diseases in high-risk adults.16,17 Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is a well-described structured program and has been used extensively in medical research for stress-related diseases.18,19 The Improving Mothers for a Better Prenatal Care Trial Barcelona (IMPACT BCN) was a randomized clinical trial designed to investigate whether structured interventions based on a Mediterranean diet or MBSR in high-risk pregnancies can reduce the percentage of newborns born small for gestational age (SGA) and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.20,21 The trial included 1221 pregnant individuals and demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of SGA (14.0% with SGA in the Mediterranean diet and 15.6% in the stress reduction group compared to 21.9% in the nonintervention group).21 Here, we report the results of a prespecified secondary end point of this trial to test the hypothesis that maternal Mediterranean diet or stress reduction interventions during pregnancy improved offspring’s neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition (Bayley-III).

Methods

Study Design, Population, and Ethics

The IMPACT BCN was a parallel, unblinded, randomized clinical trial conducted at BCNatal (Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Déu), a large referral center for maternal-fetal and neonatal medicine in Barcelona, Spain. Enrollment took place from February 2017 to October 2019 with follow-up until delivery (final follow-up on March 1, 2020). The study population included pregnant individuals recruited at midgestation (19.0 to 23.6 weeks) who were considered at high risk of delivering newborns who were SGA, according to the criteria of the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists.22 Race and ethnicity were recorded, as defined by the participants among fixed categories in a self-report questionnaire, to provide information about the generalizability of the results of the trial. Details of the trial design are provided in the protocol,20 which is available in Supplement 1. The protocol was approved by the Hospital Clínic research ethics committee, and all individuals who agreed to participate provided written informed consent before randomization. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. Data were analyzed from July to November 2022.

Randomization

Participants were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio into 3 groups: a nutritional intervention based on Mediterranean diet with supplementation of extra virgin olive oil and walnuts, a stress reduction intervention based on an MBSR program, and a control group without any intervention (usual care). Randomization was performed immediately after participants signed the informed consent form, using a web-based system and a computer-generated random number. Details are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 2. All participants attended the baseline visit at enrollment (19 to 23 weeks’ gestation) and a final visit at the end of interventions (34 to 36 weeks’ gestation), during which they responded to several questionnaires and provided biological samples and perinatal data were collected.

Outcomes

The prespecified primary end point of the trial (percentage of newborns who were SGA) and the secondary end point related to perinatal period (adverse perinatal outcome) have been published elsewhere.21 Among prespecified secondary end points for which the trial was powered, neurodevelopmental evaluation of the offspring by the Bayley-III scale at corrected postnatal age 2 years was still ongoing when the main outcome of the trial was published.21 For this study, the main prespecified outcome was the scores of each domain of the Bayley-III scale (cognitive, language, motor, social-emotional, and adaptive). The cognitive scale measures sensorimotor development, object relatedness, and concept formation; the language scale assesses receptive and expressive communication; the motor scale evaluates both fine and gross motor skills; the social-emotional scale assesses the development of relationships and interactions; and the adaptive behavior scale assesses how the child applies their developmental skills to daily living.23 In addition, we assessed the associations between Bayley-III scores and questionnaires and biomarkers related to the interventions.

Interventions During Pregnancy

The dietary intervention was based on traditional Mediterranean diet, adapted to pregnancy from the PREDIMED trial.16 The intervention was composed of monthly individual 30-minute visit assessments and a monthly 1-hour group sessions, both provided by trained nutritionists, from recruitment (19 to 23 weeks) until the end of the intervention (34 to 36 weeks), with a median (IQR) duration of 12.1 (10.7-13.3) weeks. In addition, participants in this group were provided with extra virgin olive oil (2 L every month) and walnuts (450 g every month) at no cost and specific materials were given at each visit, including recipes, a 1-week shopping list of food items according to the season of the year, and a weekly meal plan with detailed menus. Additional details of the intervention are provided elsewhere.20,21

In the stress reduction group, participants were provided with an MBSR program adapted for pregnancy, with meditations focused on the relationship with the fetus and prenatal yoga sessions. The program included formal and informal techniques with the goal of enhancing nonjudgmental presence-focused awareness, reducing rumination and anxiety, and increasing the ability to deal more effectively with stress. The program consisted of 8 weeks of weekly group classes (20 to 25 women per group) of 2.5 hours, 1 full day session, and daily home practice. The sessions included didactic presentations, formal 45-minute meditation practices with various mindfulness meditations, mindful yoga, body awareness, and group discussion. MP3 files or CDs of formal meditations adapted to pregnancy were provided for home practice. Additional details of the intervention are provided elsewhere.20,21 Participants who were randomized to the usual care group received usual pregnancy care following institutional protocols.

Measurements

Bayley-III

The Bayley-III was conducted for all participants in the IMPACT BCN trial at the corrected age of 24 months. The Bayley-III is a gold standard series of behavioral assessments used to evaluate the developmental functioning of young children.23,24 The rigorous psychometric properties of the tool are attributed to the carefully standardized normative samples and quantitative scoring system throughout 5 domains: cognitive, language, motor, social-emotional and adaptive behavior.25 The evaluations of cognitive, language, motor domains were done by 2 trained psychologists (A.C. and M.P.) who were blinded to the study groups and perinatal outcomes. For the remaining domains, parents filled in the paper format questionnaires at the assessment visit. The raw scores for each domain are standardized to a mean of 100 with a standard deviation of 15. Delayed performance in each domain was defined by a score below 85 (−1 SD).26

Mediterranean Diet Assessment

Nutritional information, including a validated 151-item food frequency questionnaire27 and the Mediterranean diet adherence score obtained from a 17-item dietary assessment questionnaire, was collected at enrollment (19 to 23 weeks, baseline visit) and at the end of the interventions (34 to 36 weeks, final visit) from all participants. Total fatty acid intake and fatty acid profile, derived from the food frequency questionnaire, were calculated on the basis of Spanish food consumption guidelines,28,29 and participants were classified into class of fatty acid intake (low, medium, and high intake). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet intervention was considered high when a participant had improved the adherence score 3 points or more at the final visit compared to their baseline visit. Additionally, in a subsample of participants randomly selected from the 3 study groups (n = 291 mothers of the 626 children [46.5%]), several biomarkers were assessed at baseline and final visits to evaluate the degree of compliance of the Mediterranean diet intervention: plasma oleic, α-linoleic, and α-linolenic acids (biomarkers of walnut consumption) and urinary hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol metabolites (biomarkers of olive oil consumption).

Stress Reduction Assessment

All participants included in the trial also provided 4 types of self-reported lifestyle questionnaires to measure their anxiety, well-being, and mindful state: the Perceived Stress Scale,30 which measures the perception of stress with anchors from never to very often (score range, 0-40); the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory personality and anxiety questionnaires that measure trait and state of anxiety, with anchors from not at all to very much (score range, 0-80); the World Health Organization Five Well-being Index,31 which measures subjective quality of life and psychological well-being, with anchors from all of the time to at no time (score range, 0-100); and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire,32 which measures mindfulness with regards to thoughts, experiences and action in daily life with anchors from always true to never (score range, 8-40 for the observation, description, awareness, and nonjudgmental facets and 7-35 for the nonreactivity facet). All questionnaires were filled out twice during the trial, at baseline and at the final visit. Participants’ well-being status was classified according to their World Health Organization Five Well-being Index as poor (≤52) or favorable (>52).33 Adherence to the stress reduction intervention was considered high when a participant attended at least 6 of the 9 sessions.

Additionally, in a subsample of randomly selected participants from all 3 groups (26.5%, excluding those receiving corticosteroid treatment), maternal 24-hour urinary cortisone and cortisol were measured.34 The cortisone/cortisol ratio was calculated as an estimate of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 activity at baseline and the final visit as a surrogate of maternal stress.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size calculation for this specific study was based on the previous data from our group35 and is provided in the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan (Supplement 1).20 In brief, aiming for a power of 80% and assuming a type I error of 5%, the sample size estimate for the outcome was 87 participants per group. Considering a loss of 30%, the final sample size calculated was 124 participants per group (total = 372).

Participants were analyzed according to their randomization group, excluding those who withdrew consent for participation in the trial and those whose fetuses or neonates had a malformation diagnosed during pregnancy or in the postnatal period. The normal distribution of variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test and histograms. Data are presented as means with SDs, medians with IQRs, or numbers with percentages, as appropriate. Comparisons among study groups were assessed by the Student t test for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables to compare each intervention group with the usual care group or high score vs low score, as appropriate. Likewise, the characteristics of patients originally included in the IMPACT BCN trial but who did not participate in the Bayley-III assessment were evaluated and compared with those of participants. According to the statistical analysis plan of the trial, for the analyses of the secondary end points, no imputations of missing data had to be made.

The main end point of this study, as a prespecified secondary outcome of the IMPACT BCN trial, was the 5 domain scores of the Bayley-III evaluation. Comparisons of the composite scores among study groups were analyzed by a linear regression unadjusted analysis. The rates of children with a score less than 85 were analyzed by χ2 test. In addition, for composite scores, a linear regression analysis adjusting for variables considered predictive of neurodevelopment at 24 months was performed, including maternal socioeconomic status and fetal sex. For the main end point of the study both models are reported. The Bayley-III evaluation was also compared in the children who were SGA and those who were not.

Exploratory analyses in the whole study population were performed by linear regression with the adjusted model as detailed above to assess the association of Bayley-III with aspects of maternal diet or stress at the final visit, including Mediterranean diet adherence score, the profile of fatty acid intake (low vs high), the levels of biomarkers of olive oil and walnut consumption, the levels of maternal stress and anxiety (assessed by Perceived Stress Scale and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory questionnaires), maternal well-being (poor vs favorable World Health Organization Five Well-being Index scores), maternal mindful state (Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire), and levels of 24-hour urinary cortisone/cortisol.

Analysis of covariance was used to compare the final scores of the biomarker values and the questionnaire scores adjusted for the baseline values. Parametric mediation analyses was conducted to generate evidence about the mechanisms by which interventions may influence the outcomes (eMethods in Supplement 2).36

Differences were considered statistically significant at P < .05. Statistical comparisons and adjusted means were computed with the emmeans library in R version 1.8.2 (R Foundation). The mediation analysis was done with mediation package in R version 4.5.0.37 Statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.0.5 (R Foundation), RStudio version 1.4.1106 (Rstudio), and Stata version 16 (StataCorp).

Results

Study Population

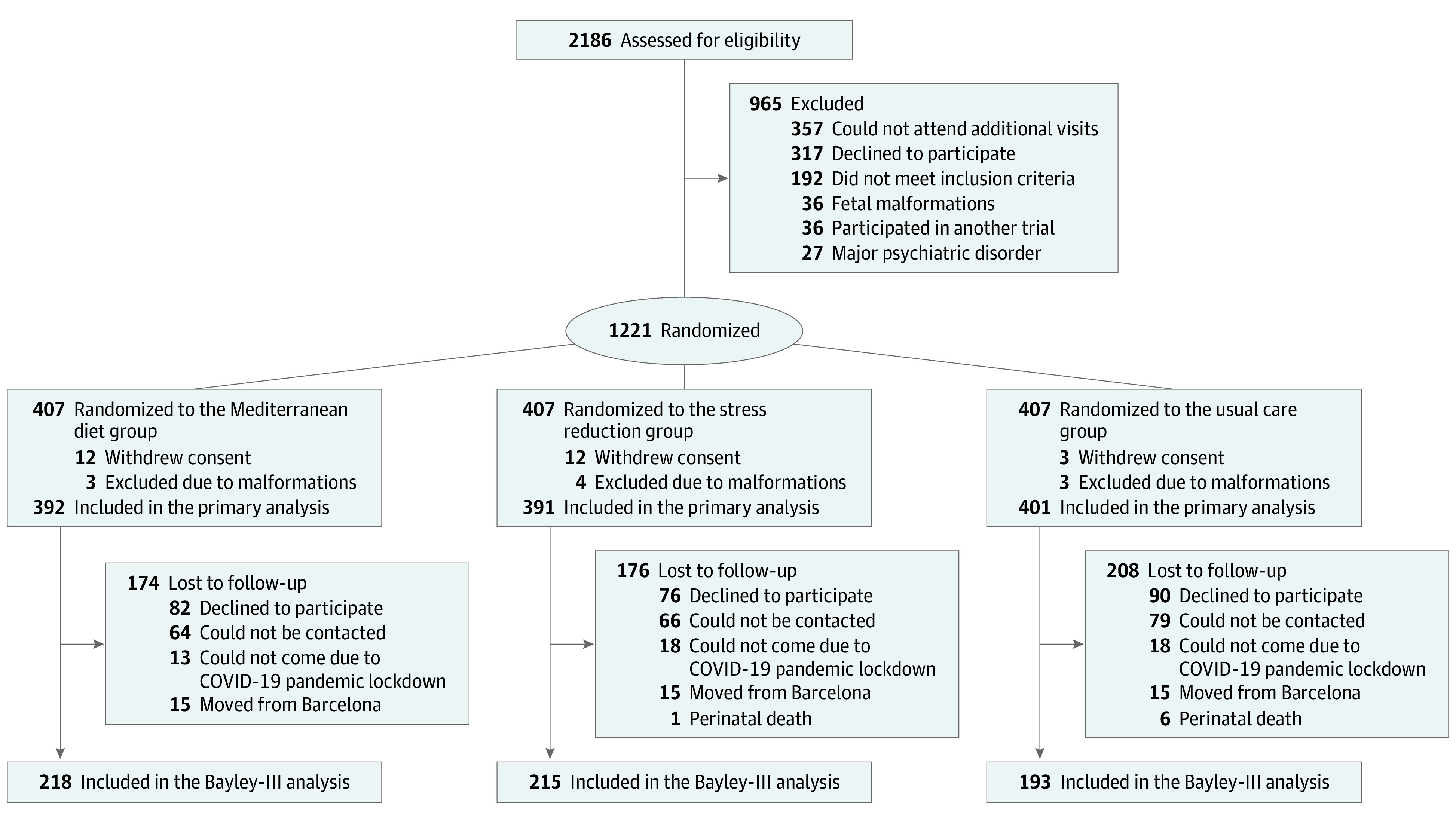

Among 1221 pregnant women randomized in the IMPACT BCN trial (Figure), 626 (51%) children (293 [46.8%] female and 333 [53.2%] male; mean [SD] age, 24.8 [2.9] months) were evaluated for Bayley-III assessment, 37 (3%) were excluded due to either withdrawal of consent or malformation, and 558 (46%) were either not located or declined to participate (eFigure 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Maternal, neonatal, and child characteristics of those evaluated for Bayley-III assessment were similar among study groups (Table 1). Adherence was high in 177 participants (71.8%) in the Mediterranean diet intervention and 137 (63.7%) in the stress reduction intervention.

Figure. Eligibility, Randomization, and Follow-Up.

Table 1. Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Characteristics by Intervention Group With Bayley-III Assessment (N = 626).

| Characteristic | Intervention, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean diet (n = 218) | Stress reduction (n = 215) | Usual care (n = 193) | |

| Maternal | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 38.0 (4.0) | 37.6 (4.5) | 37.6 (4.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| African American | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 4 (2.1) |

| Asian | 2 (0.9) | 5 (2.3) | 5 (2.6) |

| Latin American | 31 (14.2) | 28 (13.0) | 22 (11.4) |

| Maghreb | 6 (2.8) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.6) |

| White | 177 (81.2) | 177 (82.3) | 159 (82.4) |

| Socioeconomic statusa | |||

| Low | 7 (3.2) | 9 (4.2) | 14 (7.3) |

| Medium | 66 (30.3) | 72 (33.5) | 59 (30.6) |

| High | 145 (66.5) | 134 (62.3) | 120 (62.2) |

| Education | |||

| None/primary | 7 (3.2) | 9 (4.2) | 14 (7.3) |

| Secondary/technology | 54 (24.8) | 62 (28.8) | 55 (28.5) |

| University | 157 (72.0) | 144 (67.0) | 124 (64.2) |

| Cigarette smoking | 31 (14.2) | 40 (18.6) | 30 (15.5) |

| Alcohol intake | 28 (12.8) | 34 (15.8) | 23 (11.9) |

| Drug use | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.6) |

| Neonatal | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 110 (50.5) | 99 (46.0) | 84 (43.5) |

| Male | 108 (49.5) | 116 (54.0) | 109 (56.5) |

| Gestational age at delivery, median (IQR), wk | 40.0 (39.1-40.4) | 39.9 (38.6-40.4) | 39.6 (38.6-40.4) |

| Cesarean delivery | 81 (37.2) | 68 (31.6) | 60 (31.1) |

| Birthweight, mean (SD), g | 3244.8 (509.3) | 3205.3 (513.0) | 3154.7 (517.0) |

| Birthweight percentile | 43.7 (29.7) | 44.2 (29.1) | 40.7 (30.5) |

| Small for gestational age (<10th centile) | 35 (16.1) | 32 (14.9) | 40 (20.7) |

| Apgar 5 min <7 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Umbilical artery pH, mean (SD) | 7.21 (0.08) | 7.21 (0.08) | 7.20 (0.09) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 10 (4.6) | 14 (6.5) | 11 (5.7) |

| Child (at Bayley-III assessment) | |||

| Corrected age at Bayley-III assessment, mean (SD), mo | 25.1 (3.4) | 24.9 (2.7) | 24.7 (2.7) |

| Maternal breastfeeding | 192 (88.1) | 185 (86.0) | 167 (86.5) |

| Duration of breastfeeding, mean (SD), mo | 11.9 (8.7) | 12.1 (9.2) | 13.1 (9.4) |

| Breastfeeding >4 mo | 175 (80.3) | 170 (79.1) | 156 (80.8) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 86.6 (4.6) | 87.0 (5.3) | 86.9 (4.0) |

| Weight, mean (SD), g | 12.4 (1.8) | 12.5 (2.0) | 12.4 (1.6) |

| Head circumference, mean (SD), cm | 48.1 (2.8) | 48.1 (2.0) | 48.6 (2.3) |

| Attending kindergarten at Bayley-III assessment | 173 (79.4) | 157 (73.0) | 140 (72.5) |

Abbreviation: Bayley III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition.

Socioeconomic status was defined as follows: low (never worked or unemployed for more than 2 years), medium (secondary studies and work), and high (university studies and work).

Bayley-III

The Bayley-III assessment was performed from May 2019 to June 2022 at a median (IQR) of 24.1 (23.5-25.0) months after birth, with similar age among study groups (Table 1). Children from the Mediterranean diet group had significantly higher scores in the cognitive domain (mean [SD], 123.6 [17.8] vs 118.6 [18.3]; β, 5.02; 95% CI, 1.52-8.53; P = .005), and the social-emotional domain (mean [SD], 108.6 [22.0] vs 103.4 [18.5]; β, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.18-9.12; P = .01), and those from the stress reduction group had significantly higher scores in the social-emotional domain (mean [SD], 108.2 [24.0] vs 103.4 [18.5]; β, 4.75; 95% CI, 0.54-8.85; P = .02), compared to usual care (Table 2), although the effect sizes were small . These differences remained similar after adjusting for maternal socioeconomic status and fetal sex (eResults and eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Language, motor, and adaptive scores were similar among study groups (Table 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 2). No differences in Bayley-III scores were observed between children who were SGA and those who were not (eResults and eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Bayley-III Scores for Children by Intervention Group (N = 626).

| Bayley-III domain | Mediterranean diet (n = 218) | Stress reduction (n = 215) | Usual care (n = 193) | Mediterranean diet vs usual care | Stress reduction vs usual care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Cognitive composite score, mean (SD) | 123.6 (17.8) | 119.3 (19.6) | 118.6 (18.3) | 5.02 (1.52 to 8.53) | .005 | 0.67 (−3.02 to 4.38) | .72 |

| Cognitive score <85, No. (%) | 2 (0.9) | 8 (3.7) | 7 (3.6) | NA | .06 | NA | .96 |

| Language composite score, mean (SD)a | 107.9 (19.2) | 104.7 (17.7) | 105.5 (17.0) | 2.40 (−1.15 to 5.96) | .18 | −0.78 (−4.20 to 2.63) | .65 |

| Language score <85, No. (%)a | 15 (6.9) | 19 (8.9) | 16 (8.5) | NA | .55 | NA | .86 |

| Motor composite score, mean (SD)b | 113.3 (14.4) | 113.4 (13.9) | 114.7 (13.8) | −1.40 (−4.17 to 1.33) | .31 | −1.37 (−4.07 to 1.34) | .32 |

| Motor score <85, No. (%)b | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) | NA | .06 | NA | .27 |

| Social-emotional composite score, mean (SD)c | 108.6 (22.0) | 108.2 (24.0) | 103.4 (18.5) | 5.15 (1.18 to 9.12) | .01 | 4.75 (0.54 to 8.85) | .02 |

| Social-emotional score <85, No. (%)c | 24 (11.1) | 23 (10.7) | 28 (14.5) | NA | .30 | NA | .25 |

| Adaptive composite score, mean (SD)d | 94.8 (16.3) | 93.0 (16.5) | 94.0 (15.5) | 0.82 (−2.28 to 3.92) | .60 | −0.99 (−4.12 to 2.13) | .53 |

| Adaptive score <85, No. (%)d | 50 (23.1) | 58 (26.9) | 51 (26.4) | NA | .44 | NA | .90 |

Abbreviations: Bayley III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition; NA, not applicable.

n = 620.

n = 625.

n = 624.

n = 624.

Association Between Mediterranean Diet Assessment Variables and Bayley-III

Maternal adherence to Mediterranean diet, fatty acid intake, and biomarkers of olive oil and walnut consumption are reported in eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 2. In the whole study population, the Mediterranean diet score showed significant positive associations with the cognitive and language Bayley-III domains (eResults and eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Association between Bayley-III and fatty acid intake or nutritional biomarkers are reported in eTables 6 and 7, respectively, in Supplement 2. Among other findings, higher intake of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) was associated with significantly better language scores, while higher intake of trans fatty acids was inversely associated with social-emotional scores and language scores. Mediation analysis results are reported in the eResults and eFigures 5 to 9 in Supplement 2.

Association Between Maternal Stress Assessment Variables and Bayley-III

Maternal adherence to the stress reduction intervention during pregnancy is reported in eTable 8 in Supplement 2. In the whole study population, the levels of maternal stress and anxiety during pregnancy showed negative significant associations with all 5 Bayley-III domains (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Higher maternal well-being in the World Health Organization Five Well-being Index (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2) was associated with higher scores in the Bayley-III language, social-emotional, and adaptive behavior domains. There were positive associations in the maternal mindful state and several domains of the Bayley-III in the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire description and awareness scores (eTable 9 in Supplement 2). The levels of 24-hour urinary cortisone/cortisol showed a positive significant association with the language domain and a nonsignificant positive trend with the cognitive domain (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Mediation analysis results are reported in eFigures 5-7 and 10 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

In this prespecified analysis of the IMPACT BCN randomized clinical trial, structured maternal lifestyle interventions based on Mediterranean diet or stress reduction during pregnancy resulted in better scores in the cognitive and social-emotional domains of the Bayley-III scale scores of children at age 2 years. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized clinical trial evaluating the effects of maternal lifestyle interventions based on Mediterranean diet or stress reduction on child neurodevelopment.

The association between maternal diet and offspring neurodevelopment has been suggested by several epidemiological studies.6,38,39 It has been proposed that several dietary components may mediate changes in inflammatory status interfering with brain development in utero. Three randomized clinical trials have evaluated the effects of DHA supplements during pregnancy on child neurodevelopment. The largest of these studies40 evaluated 726 children at 18 months of age and reported no differences in Bayley-III scores. Another study evaluated 86 children at 43 weeks of age41 and reported larger total brain volumes, total gray matter, and corpus callosum as assessed by magnetic resonance in children whose mothers received DHA supplementation during pregnancy. The KUDOS trial42 included 301 mothers and reported that DHA supplementation was associated with higher sustained attention on habituation tasks at age 4 to 9 months but not after age 18 months. The positive findings in our study may be explained by the use of a healthy dietary pattern instead of supplementation with a specific nutrient. It has been proposed that the synergistic actions of several dietary components, including long-chain polysaturated fatty acids, monosaturated fatty acids from extra virgin olive oil, antioxidant vitamins, dietary fiber, and polyphenols, may explain the effects of the Mediterranean diet on reducing inflammatory and oxidative stress markers.43 In the present study, adherence to Mediterranean diet was associated with improved Bayley III scores in the whole population. In previous nonrandomized studies, maternal adherence to a Mediterranean diet in early pregnancy has been associated with favorable neurobehavioral outcomes in early childhood.6,38

Maternal psychological stress and anxiety during pregnancy have consistently been associated with adverse offspring neurodevelopment.9,44,45 A recent nonrandomized study including 161 pregnant women with low socioeconomic status and high stress levels46 reported that a mindfulness-based intervention was associated with improved biobehavioral reactivity and regulation in infants at age 6 months. These results are in agreement with the present trial, where children from the stress reduction group showed higher scores in the social-emotional domain compared with children from the usual care group. Stress reduction is a plausible mechanism for the findings of this study. Stress is associated with increased proinflammatory cytokines47,48 and cortisol.49 The deleterious effects of inflammatory mediators on fetal brain development have extensively been demonstrated in experimental and clinical studies.50,51,52,53 In line with previous studies in pregnant mothers,54 the stress reduction program was associated with improvements in anxiety, well-being, and stress biomarkers compared with the other study groups. In the whole population, higher maternal well-being and lower stress biomarkers were associated with significant improvements in several Bayley-III domains.

Previous studies report that the cognitive domain results in early infancy were associated with future intelligence quotient,55,56,57 which gives clinical importance to our findings. Actually, in accordance with other studies, a Bayley-III mean group difference greater than 5 points could be regarded as clinically important.58,59

Limitations

The study has some limitations that merit comment. First, only a proportion of children from the original IMPACT BCN trial were included; with a larger sample size, some of the trends observed may have become statistically significant. However, according to the sample size calculation, the number of participants analyzed was sufficient to observe an effect of the interventions. Second, the social-emotional and adaptative behavior items were administered by caregivers, introducing a potential source of bias. Third, the population of the original trial was not representative of a general pregnancy population since participants were selected among pregnancies at high risk for SGA. In addition, the study was conducted in a high-resource setting in a population with high levels of education and socioeconomic status and a low proportion of obesity and gestational diabetes. Again, the dropout rates were higher in those with lower socioeconomic status (eResults and eTable 1 in Supplement 2), which might have biased the results. Therefore, these findings might not be replicable in other settings. Fourth, the interventions were highly intense and required time engagement, which may not be feasible for some pregnant individuals. Fifth, the interventions may have changed maternal lifestyle after pregnancy. The differences found in Bayley-III domains might partially reflect changes in maternal lifestyle after rather than during pregnancy. Sixth, the interventions tested were associated with an improvement in SGA and other pregnancy complications. It cannot be completely excluded that the effects observed were partly mediated by a reduction in pregnancy complications, although no differences in the Bayley-III score were found between children with and without SGA in this population.

Conclusions

In this prespecified analysis of a randomized clinical trial, treating pregnant women at high risk for SGA with structured interventions based on Mediterranean diet or stress reduction significantly improved child neurodevelopment at age 2 years as assessed by Bayley-III. These results need replication in further randomized clinical trials as well as assessment in additional patient populations.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods

eResults

eTable 1. Maternal, neonatal and infants’ characteristics of individuals who did not participate in the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition (Bayley-III) assessment, according to intervention groups (n=558)

eTable 2. Adjusted comparisons of Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development examination (Bayley-III) of infants according to intervention groups (n=626)

eTable 3. Comparison of Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development examination, 3rd edition (Bayley-III) comparing appropriate versus small for gestational age newborns (n=626)

eTable 4. Maternal Mediterranean diet adherence and fatty acid intake at the final visit adjusted by baseline assessment per intervention group (n=543)

eTable 5. Maternal biomarkers of Mediterranean diet adherence at the final visit adjusted by baseline assessment per intervention group (n=291)

eTable 6. Associations between fatty acids intake according to Spanish food consumption (tertiles) at final assessment during pregnancy (34-36 weeks’ gestation) and the infant Bayley-III results in the whole study population (n=543)

eTable 7. Association between biomarkers related to Mediterranean diet at 34-36 weeks’ gestation and the infant Bayley-III results in the whole study population (n=290)

eTable 8. Maternal lifestyle questionnaires and biological sample related to maternal stress, well-being and mindful state at the final visit adjusted by baseline assessment per intervention group

eTable 9. Association between maternal mindful state (FFMQ) at final assessment during pregnancy (34-36 weeks’ gestation) and the infant Bayley-III results in the whole study population (n=587)

eFigure 1. Associations between maternal Mediterranean diet adherence scores during pregnancy and the infant Bayley-III domain scores

eFigure 2. Associations between maternal stress/anxiety questionnaires and the infant Bayley-III scores

eFigure 3. Associations between infant Bayley-III scores and maternal WHO-5 score

eFigure 4. Associations between infant Bayley-III scores and maternal 24h-urinary cortisone/cortisol ratio

eFigure 5. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 1

eFigure 6. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 2

eFigure 7. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 3

eFigure 8. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 4

eFigure 9. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 5

eFigure 10. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 6

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Elisenda Eixarch MP, Muñoz-Moreno E, Bargallo N, Batalle D, Gratacos E. Motor and cortico-striatal-thalamic connectivity alterations in intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):725.e1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edlow AG. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(1):95-110. doi: 10.1002/pd.4932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van den Bergh BRH, van den Heuvel MI, Lahti M, et al. Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: the influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;117:26-64. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teede HJ, Bailey C, Moran LJ, et al. Association of antenatal diet and physical activity-based interventions with gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(2):106-114. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marques AH, Bjørke-Monsen AL, Teixeira AL, Silverman MN. Maternal stress, nutrition and physical activity: impact on immune function, CNS development and psychopathology. Brain Res. 2015;1617:28-46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steenweg-de Graaff J, Tiemeier H, Steegers-Theunissen RPM, et al. Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and child internalising and externalising problems. the Generation R Study. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(1):115-121. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbonaite G, Knyzeliene A, Bunn FS, Smalskys A, Neniskyte U. The impact of maternal high-fat diet on offspring neurodevelopment. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:909762. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.909762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y, Kapse K, Jacobs M, et al. Association of Maternal psychological distress with in utero brain development in fetuses with congenital heart disease. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):e195316. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Espinosa KM, Barnett SD, et al. Association of elevated maternal psychological distress, altered fetal brain, and offspring cognitive and social-emotional outcomes at 18 months. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e229244. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.9244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bock J, Wainstock T, Braun K, Segal M. Stress in utero: prenatal programming of brain plasticity and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(5):315-326. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anifantaki F, Pervanidou P, Lambrinoudaki I, Panoulis K, Vlahos N, Eleftheriades M. Maternal prenatal stress, thyroid function and neurodevelopment of the offspring: a mini review of the literature. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:692446. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.692446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ros E, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, et al. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular health: teachings of the PREDIMED study. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(3):330S-336S. doi: 10.3945/an.113.005389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saban KL, Collins EG, Mathews HL, et al. Impact of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program on psychological well-being, cortisol, and inflammation in women veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(S3)(suppl 3):751-761. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07584-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witek Janusek L, Tell D, Mathews HL. Mindfulness based stress reduction provides psychological benefit and restores immune function of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: A randomized trial with active control. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:358-373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambring A, Johansson M, Axelsen M, Gan L, Strandvik B, Friberg P. Mediterranean-inspired diet lowers the ratio of serum phospholipid n-6 to n-3 fatty acids, the number of leukocytes and platelets, and vascular endothelial growth factor in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(3):575-581. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. ; PREDIMED Study Investigators . Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):e34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, et al. Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1094-1103. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabat-Zinn J. Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. In: Full Catastrophe Living. Piatkus; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2):169-183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crovetto F, Crispi F, Borras R, et al. Mediterranean diet, mindfulness-based stress reduction and usual care during pregnancy for reducing fetal growth restriction and adverse perinatal outcomes: IMPACT BCN (Improving Mothers for a Better Prenatal Care Trial Barcelona): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):362. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05309-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crovetto F, Crispi F, Casas R, et al. ; IMPACT BCN Trial Investigators . Effects of Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction on prevention of small-for-gestational age birth weights in newborns born to at-risk pregnant individuals: the IMPACT BCN randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(21):2150-2160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.20178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowley T. Small-for-gestational-age fetus, investigation and management. Published online January 21, 2014. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/small-for-gestational-age-fetus-investigation-and-management-green-top-guideline-no-31/

- 23.Del Rosario C, Slevin M, Molloy EJ, Quigley J, Nixon E. How to use the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2021;106(2):108-112. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Third edition. Pearson; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torras-Mañá M, Gómez-Morales A, González-Gimeno I, Fornieles-Deu A, Brun-Gasca C. Assessment of cognition and language in the early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: usefulness of the Bayley Scales of infant and toddler development. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2016;60(5):502-511. doi: 10.1111/jir.12291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson S, Moore T, Marlow N. Using the Bayley-III to assess neurodevelopmental delay: which cut-off should be used? Pediatr Res. 2014;75(5):670-674. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juton C, Castro-barquero S, Casas R, et al. Reliability and concurrent and construct validity of a food frequency questionnaire for pregnant women at high risk to develop fetal growth restriction. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1629. doi: 10.3390/nu13051629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mataix J. Tablas de Composición de Alimentos. Food Composition Tables. 4th ed. Universidad de Granada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Hoyos MDCC. Tablas de Composición de Alimentos. Guía de Prácticas; Ediciones Pirámide. Grupo Anaya; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bech P, Olsen LR, Kjoller M, Rasmussen NK. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: a comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five Well-Being Scale. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(2):85-91. doi: 10.1002/mpr.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27-45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonnín CM, Yatham LN, Michalak EE, et al. Psychometric properties of the well-being index (WHO-5) Spanish version in a sample of euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;228(228):153-159. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcos J, Renau N, Casals G, Segura J, Ventura R, Pozo OJ. Investigation of endogenous corticosteroids profiles in human urine based on liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2014;812:92-104. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savchev S, Sanz-Cortes M, Cruz-Martinez R, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of full-term small-for-gestational-age infants with normal placental function. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(2):201-206. doi: 10.1002/uog.12391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H, Cashin AG, Lamb SE, et al. ; AGReMA group . A guideline for reporting mediation analyses of randomized trials and observational studies: the AGREMA statement. JAMA. 2021;326(11):1045-1056. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J Stat Softw. 2014;59(5). doi: 10.18637/jss.v059.i05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.House JS, Mendez M, Maguire RL, et al. Periconceptional maternal mediterranean diet is associated with favorable offspring behaviors and altered CpG methylation of imprinted genes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:107. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tahaei H, Gignac F, Pinar A, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid intake during pregnancy and child neuropsychological development: a multi-centre population-based birth cohort study in Spain. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):518. doi: 10.3390/nu14030518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, Yelland L, Quinlivan J, Ryan P; DOMInO Investigative Team . Effect of DHA supplementation during pregnancy on maternal depression and neurodevelopment of young children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1675-1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogundipe E, Tusor N, Wang Y, Johnson MR, Edwards AD, Crawford MA. Randomized controlled trial of brain specific fatty acid supplementation in pregnant women increases brain volumes on MRI scans of their newborn infants. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2018;138:6-13. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colombo J, Shaddy DJ, Gustafson K, et al. The Kansas University DHA Outcomes Study (KUDOS) clinical trial: long-term behavioral follow-up of the effects of prenatal DHA supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1380-1392. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwingshackl L, Morze J, Hoffmann G. Mediterranean diet and health status: active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(6):1241-1257. doi: 10.1111/bph.14778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamayo Y Ortiz M, Téllez-Rojo MM, Trejo-Valdivia B, et al. Maternal stress modifies the effect of exposure to lead during pregnancy and 24-month old children’s neurodevelopment. Environ Int. 2017;98:191-197. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindsay KL, Buss C, Wadhwa PD, Entringer S. The interplay between nutrition and stress in pregnancy: implications for fetal programming of brain development. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85(2):135-149. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noroña-Zhou AN, Coccia M, Epel E, et al. The effects of a prenatal mindfulness intervention on infant autonomic and behavioral reactivity and regulation. Psychosom Med. 2022;84(5):525-535. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000001066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(3):774-815. doi: 10.1037/a0035302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maydych V. The interplay between stress, inflammation, and emotional attention: relevance for depression. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell G, Lightman S. The human stress response. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(9):525-534. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0228-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith SEP, Li J, Garbett K, Mirnics K, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J Neurosci. 2007;27(40):10695-10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osborne S, Biaggi A, Chua TE, et al. Antenatal depression programs cortisol stress reactivity in offspring through increased maternal inflammation and cortisol in pregnancy: the Psychiatry Research and Motherhood-Depression (PRAM-D) Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;98:211-221. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudolph MD, Graham AM, Feczko E, et al. Maternal IL-6 during pregnancy can be estimated from newborn brain connectivity and predicts future working memory in offspring. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(5):765-772. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0128-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalish BT, Kim E, Finander B, et al. Maternal immune activation in mice disrupts proteostasis in the fetal brain. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(2):204-213. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00762-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo P, Zhang X, Liu N, et al. Mind-body interventions on stress management in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(1):125-146. doi: 10.1111/jan.14588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bode MM, D’Eugenio DB, Mettelman BB, Gross SJ. Predictive validity of the Bayley, third edition at 2 years for intelligence quotient at 4 years in preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(9):570-575. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishijima M, Yoshida T, Matsumura K, et al. Correlation between the Bayley-III at 3 years and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, fourth edition, at 6 years. Pediatr Int. 2022;64(1):e14872. doi: 10.1111/ped.14872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Månsson J, Källén K, Eklöf E, Serenius F, Ådén U, Stjernqvist K. The ability of Bayley-III scores to predict later intelligence in children born extremely preterm. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(11):3030-3039. doi: 10.1111/apa.16037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serenius F, Kallen K, Blennow M, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in extremely preterm infants at 2.5 years after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA. 2013;309(17):1810-1820. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cartwright RD, Crowther CA, Anderson PJ, Harding JE, Doyle LW, McKinlay CJD. Association of fetal growth restriction with neurocognitive function after repeated antenatal betamethasone treatment vs placebo: secondary analysis of the ACTORDS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187636. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods

eResults

eTable 1. Maternal, neonatal and infants’ characteristics of individuals who did not participate in the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition (Bayley-III) assessment, according to intervention groups (n=558)

eTable 2. Adjusted comparisons of Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development examination (Bayley-III) of infants according to intervention groups (n=626)

eTable 3. Comparison of Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development examination, 3rd edition (Bayley-III) comparing appropriate versus small for gestational age newborns (n=626)

eTable 4. Maternal Mediterranean diet adherence and fatty acid intake at the final visit adjusted by baseline assessment per intervention group (n=543)

eTable 5. Maternal biomarkers of Mediterranean diet adherence at the final visit adjusted by baseline assessment per intervention group (n=291)

eTable 6. Associations between fatty acids intake according to Spanish food consumption (tertiles) at final assessment during pregnancy (34-36 weeks’ gestation) and the infant Bayley-III results in the whole study population (n=543)

eTable 7. Association between biomarkers related to Mediterranean diet at 34-36 weeks’ gestation and the infant Bayley-III results in the whole study population (n=290)

eTable 8. Maternal lifestyle questionnaires and biological sample related to maternal stress, well-being and mindful state at the final visit adjusted by baseline assessment per intervention group

eTable 9. Association between maternal mindful state (FFMQ) at final assessment during pregnancy (34-36 weeks’ gestation) and the infant Bayley-III results in the whole study population (n=587)

eFigure 1. Associations between maternal Mediterranean diet adherence scores during pregnancy and the infant Bayley-III domain scores

eFigure 2. Associations between maternal stress/anxiety questionnaires and the infant Bayley-III scores

eFigure 3. Associations between infant Bayley-III scores and maternal WHO-5 score

eFigure 4. Associations between infant Bayley-III scores and maternal 24h-urinary cortisone/cortisol ratio

eFigure 5. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 1

eFigure 6. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 2

eFigure 7. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 3

eFigure 8. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 4

eFigure 9. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 5

eFigure 10. Mediation analysis models of intervention mechanisms*, Casual Model 6

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement