Abstract

Aims

Combined anatomical and functional imaging enables detection of non-obstructive and obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) as well as myocardial ischaemia. We evaluated sex differences in disease profile and outcomes after combined computed tomography angiography (CTA) and positron emission tomography (PET) perfusion imaging in patients with suspected obstructive CAD.

Methods and results

We retrospectively evaluated 1948 patients (59% women) referred for coronary CTA due to suspected CAD during the years 2008–2016. Patients with a suspected obstructive lesion on coronary CTA (n = 657) underwent 15O-water PET to assess stress myocardial blood flow (MBF). During a mean follow-up of 6.8 years, 182 adverse events (all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina) occurred. Women had more often normal coronary arteries (42% vs. 22%, P < 0.001) and less often abnormal stress MBF (9% vs. 28%, P < 0.001) than men. The annual adverse event rate was lower in women vs. men (1.2% vs. 1.7%, P = 0.02). Both in women and men, coronary calcification, non-obstructive CAD, and abnormal stress MBF were independent predictors of events. Abnormal stress MBF was associated with 5.0- and 5.6-fold adverse event rates in women and men, respectively. There was no interaction between sex and coronary calcification, non-obstructive CAD, or abnormal stress MBF in terms of predicting adverse events.

Conclusion

Among patients evaluated for chronic chest pain, women have a lower prevalence of ischaemic CAD and a lower rate of adverse events. Combined coronary CTA and PET myocardial perfusion imaging predict outcomes equally in women and men.

Keywords: chronic chest pain, computed tomography angiography, coronary artery disease, positron emission tomography, hybrid imaging, sex

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

There are differences in the diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests to assess obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) between women and men.1–3 Recent comparative studies indicate that in women anatomic evaluation by coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) is associated with a lower rate of CAD diagnosis than noninvasive functional tests as compared to men.4–6 Furthermore, women may gain similar or even more prognostic information from coronary CTA than stress testing for ischaemia, whereas men benefit equally from both of these testing modalities.4–6

Hybrid or combined imaging using coronary CTA and functional testing for ischaemia enables accurate detection of non-obstructive and obstructive CAD as well as assessment of the haemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis.7,8 Clinical practice guidelines recommend functional evaluation of CAD before revascularization decisions.9 We have constructed an observational registry of patients in whom the haemodynamic significance of any suspected obstructive stenosis detected by coronary CTA was routinely evaluated by 15O-water positron emission tomography (PET) myocardial perfusion imaging.10 We previously demonstrated that normal stress myocardial blood flow (sMBF) despite obstructive CAD on CTA, is associated with favourable prognosis.10 However, the prognostic value of combined anatomical and functional imaging in men vs. women remains unknown.

We hypothesized that a detailed assessment of CAD by combining anatomical and functional imaging reveals differences in characteristics of CAD, while the prognostic value of diagnostic testing in women vs. men with chronic chest pain would be the same. For this purpose, we compared the findings and prognostic value of combined coronary CTA and 15O-water PET perfusion imaging among women and men with suspected CAD.

Methods

Study cohort

We retrospectively identified all consecutive patients referred for coronary CTA in the Turku PET Centre due to suspected obstructive CAD in the period of 2008–2016. We did not include patients with known CAD (previous coronary revascularization or ≥50% diameter stenosis on invasive coronary angiography, ICA) or those referred primarily for reasons other than suspected symptomatic CAD, such as aetiological evaluation of heart failure or pre-operative evaluation. In cases of repeat tests during the study period, only the earliest test was included in the current analysis.

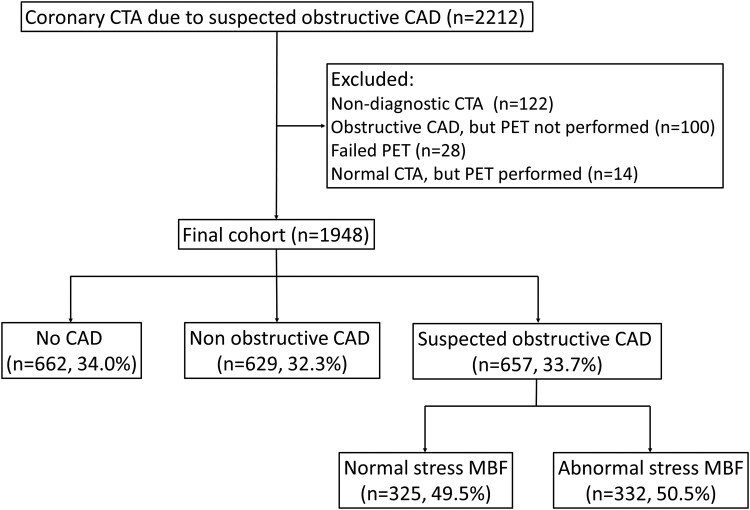

As previously described,10,11 it is routine practice in our hospital that patients initially undergo coronary CTA using a hybrid PET-CT scanner, and immediately after coronary CTA, the attending physician evaluates the CTA scan to decide whether to perform PET myocardial perfusion imaging during the same visit. If the coronary CTA reveals obstructive CAD (diameter stenosis ≥50%), the haemodynamic significance of lesions is evaluated using 15O-water PET during adenosine stress. Out of the 2212 patients identified, we excluded 122 patients who did not complete the combined imaging protocol for reasons outlined in Figure 1, including 61 patients referred directly for ICA without PET. Thus, the final analysis included 1948 patients.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection and classification according to imaging findings.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland approved the study protocol and waived the need for written informed consent by patients. The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare gave permission to the retrospective collection of clinical data.

Coronary CTA and PET image acquisition and interpretation

Coronary CTA and PET scans were performed using a 64-row hybrid PET-CT scanner (GE Discovery VCT or GE D690, General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, Wisconsin) using previously described procedures.7,10

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scans were performed before coronary CTA in the majority of patients. Based on the CAC score, patients were categorized into those with no coronary calcification (CAC score = 0), mild calcification (CAC score = 1–99), moderate calcification (CAC score = 100–399), and extensive calcification (CAC score ≥400).

Before coronary CTA, metoprolol was given intravenously to achieve a target heart rate of <60 beats/min. Isosorbide dinitrate aerosol (1.25 mg) was administered for coronary artery vasodilation. Coronary CTA was performed using an intravenously administered low-osmolal iodine contrast agent followed by a saline flush. The prospectively triggered acquisition was applied whenever feasible. Collimation was set at 64 × 0.625 mm, gantry rotation time was 350 ms, tube current 600–750 mA, and voltage 100–120 kV, depending on patient size. Coronary CTA scans were analysed in a standardized fashion, reporting the presence of atherosclerotic plaque and obstructive stenosis (≥50% in diameter) for each coronary artery segment.

Before the PET scan, patients fasted overnight and abstained from alcohol and caffeine for 24 h. Adenosine infusion started 2 min before the stress PET scan and continued at a rate of 140 μg/kg/min until the scan was complete. 15O-water (Radiowater Generator, Hidex Oy, Turku, Finland) was injected as an intravenous bolus (mean injected activity 900–1100 MBq) over 15 s followed by dynamic PET acquisition (14 × 5 s, 3 × 10 s, 3 × 20 s, and 4 × 30 s).

The PET data were analysed quantitatively using Carimas software (developed at Turku PET Centre, Turku, Finland). Absolute sMBF (mL/g/min) was quantified individually for each of the standard 17 myocardial segments. Basal septal segments (segments 2 and 3) were excluded from the analysis. Abnormal stress MBF was defined as ≤2.3 mL/g/min in ≥1 segment based on previous research.12

Based on both CTA and PET findings we classified patients into four categories: (i) normal coronary arteries; (ii) non-obstructive CAD based on CTA; (iii) obstructive CAD by CTA and normal sMBF; and (iv) obstructive CAD by CTA and abnormal sMBF.

Clinical and follow-up data collection

Data on traditional cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and family history of CAD), symptoms, and medications were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records.

The primary outcome was a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), or unstable angina pectoris (UAP) based on comprehensive data until May 2020 in the registries of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare and the Centre for Clinical Informatics of the Turku University Hospital. Investigators used electronic medical records to validate all adverse events. Data of early revascularization within 6 months after coronary CTA, with either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, were also collected, but not used as endpoints. In case of the occurrence of multiple adverse events, the first event was considered.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range], as appropriate. Categorical variables are shown as count (percentage). The χ2 test, Fisher Exact test, student t-test, and Mann–Whitney U test were used as appropriate. The cumulative incidence of events was based on Kaplan–Meier estimates and was compared between women and men using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify the univariable and multivariable predictors in the whole cohort, men, and women. The clinical variables bearing significant association with the composite outcome in the univariable analysis were added to the clinical multivariable model as covariates. Those covariates bearing significant association with the composite outcome in the clinical multivariable model were then transferred as covariates to multivariable models including CAC or PET-CTA findings. The prognostic value of the multivariable models to predict the composite outcome was tested using the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis and time-dependent ROC as implemented in the R package time ROC.13 The statistical difference between the ROC curves was determined using the DeLong method14 using R package pROC.15 Furthermore, the interaction between sex on one hand and either the CAC or PET-CTA findings, on the other hand, was tested using Cox proportional hazards models. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 25.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA) statistical software and R statistical computing environment version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

The cohort consisted of 1948 patients including 1147 (58.9%) women with suspected obstructive CAD who underwent coronary CTA. In 1291 (66.3%) patients, obstructive CAD was excluded based on coronary CTA alone, whereas 657 (33.7%) had 15O-water PET myocardial perfusion imaging to evaluate haemodynamic significance of suspected obstructive coronary stenosis. As shown in Figure 1, 34.0% of patients had normal coronary arteries, 32.3% had non-obstructive CAD, 16.7% had obstructive CAD on coronary CTA and normal sMBF, and 17.0% had obstructive CAD and abnormal sMBF. Supplementary data online, Figure S1 shows an example of findings.

Baseline characteristics of men vs. women

Characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Women were slightly older, and had less frequently diabetes, and more frequent family history of premature CAD than men. Women were less likely to have a smoking history than men, but there was no difference in body mass index or the prevalence of either dyslipidemia or hypertension. There were only four women and eight men with known left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction <40%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, imaging findings, and early invasive therapies of all patients, men, and women

| Cohort (n = 1948) | Men (n = 801) | Women (n = 1147) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 62.9 ± 9.6 | 59.9 ± 10.6 | 63.4 ± 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 27.9 ± 6.6 | 27.9 ± 5.7 | 28.0 ± 7.3 | 0.6 |

| Current or ex-smoking | 625 (32.1) | 338 (42.2) | 287 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 288 (14.8) | 137 (17.1) | 151 (13.2) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 1083 (55.6) | 455 (56.8) | 628 (54.8) | 0.3 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1221 (62.7) | 497 (62.0) | 724 (63.1) | 0.6 |

| Family history of CAD | 918 (47.1) | 301 (37.6) | 617 (53.8) | <0.001 |

| Typical chest pain | 411 (22.1) | 153 (20.0) | 258 (23.6) | |

| Atypical/non-cardiac chest pain | 963 (49.4) | 371 (46.3) | 592 (51.6) | |

| Dyspnoea | 755 (38.8) | 261 (32.6) | 494 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery calcium score (n = 1594) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 578 (36.3) | 152 (23.2) | 426 (45.3) | |

| 1–99 | 467 (29.3) | 185 (28.3) | 282 (30.0) | |

| 100–399 | 304 (19.1) | 159 (24.3) | 145 (15.4) | |

| > 400 | 245 (15.4) | 158 (24.2) | 87 (9.3) | |

| Coronary CTA and PET findings | <0.001 | |||

| No CAD | 662 (34.0) | 177 (22.1) | 485 (42.3) | |

| Non-obstructive CAD | 629 (32.3) | 261 (32.6) | 368 (32.1) | |

| Obstructive CAD and normal sMBF | 325 (16.7) | 136 (17.0) | 189 (16.5) | |

| Obstructive CAD and abnormal sMBF | 332 (17.0) | 227 (28.3) | 105 (9.2) | |

| Invasive coronary angiography | 217 (11.1%) | 140 (17.5) | 77 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Early revascularization (6 months) | 127 (6.5%) | 86 (10.7%) | 41 (3.6%) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 112 (5.7%) | 74 (9.2) | 38 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| CABG | 18 (0.9%) | 15 (1.9) | 3 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up events | ||||

| Death | 126 (6.5) | 60 (7.5) | 66 (5.8) | 0.1 |

| MI | 45 (2.3) | 23 (2.9) | 22 (1.9) | 0.1 |

| UAP | 21 (1.1) | 11 (1.4) | 10 (0.9) | 0.2 |

| Death or MI | 164 (8.4) | 80 (10.0) | 84 (7.3) | 0.03 |

| Death, MI or UAP | 182 (9.4) | 90 (11.3) | 92 (8.0) | 0.01 |

mean ± standard deviation (range).

CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CTA, computed tomography angiography; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PET, positron emission tomography; sMBF, stress myocardial blood flow; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

The most common presenting symptom was atypical angina or non-anginal chest pain. Typical angina was more common in women than men. Women also reported dyspnoea more often than men.

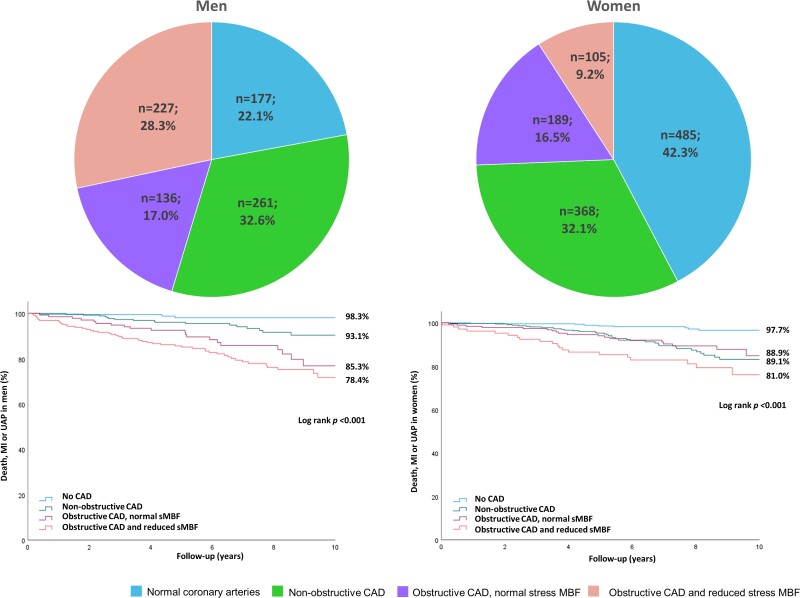

Sex differences in coronary CTA and PET perfusion findings

Women were more likely to have normal coronary arteries than men (42.3% vs. 22.1% P < 0.001) while abnormal sMBF was less frequent in women than men (9.2% vs. 28.3% P < 0.001, Table 1 and Figure 2). Hemodynamically non-significant CAD was present similarly in women and men (48.6% vs. 49.6%). However, the CAC score was higher in men than women.

Figure 2.

Graphs showing proportions of women and men with normal coronary arteries, non-obstructive CAD, obstructive CAD and normal sMBF, and obstructive CAD and abnormal sMBF.

Follow-up

The mean time of follow-up was 6.8 ± 2.5 years with a median of 6.65 years. During the follow-up, there were 126 deaths, 45 MIs, and 21 UAPs. The composite outcome of death, MI, or UAP occurred in 182 patients and was less frequent in women than men (8.0% vs. 11.3%, P = 0.01, Table 1).

Most (190 out of 217) early ICAs were performed in patients with ischaemic CAD (obstructive CAD on CTA and abnormal sMBF). Similarly, most revascularizations were performed in patients with ischaemic CAD (123 out of 127). Among 332 patients with ischaemic CAD, there was no difference in the ICA referral rate between women and men (60.0% vs. 55.9%, P = 0.4). A similar proportion of women and men with ischaemic CAD had early revascularization (36.2 vs. 37.4%, P = 0.8), and the revascularization rate among those undergoing ICA was similar (53.2% vs. 61.4%, P = 0.2). Among patients with ischaemic CAD, there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of events at long-term follow-up between patients who underwent early revascularization (17.9%) vs. were treated conservatively (22.5%, P = 0.4).

Predictors of events in women and men

Male sex was an independent risk factor for adverse events. Age and dyspnoea were associated with adverse events in women, whereas in men, age, diabetes, hypertension, and typical angina predicted events (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable predictors of adverse events (all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina pectoris) in all patients, men and women

| All patients | Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | HR (95% CI) | P value | AUC | HR (95% CI) | P value | AUC | HR (95% CI) | P value | AUC |

| Clinical | 0.706 | 0.728 | 0.705 | ||||||

| Age | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.03–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | <0.001 | |||

| Male sex | 1.81 (1.32–2.46) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Diabetes | 1.77 (1.09–2.89) | 0.03 | |||||||

| Hypertension | 1.61 (1.15–2.25) | 0.004 | 2.03 (1.21–3.40) | 0.009 | |||||

| Typical angina | 1.55 (1.10–2.18) | 0.01 | 2.01 (1.24–3.25) | 0.01 | |||||

| Dyspnoea | 1.60 (1.17–2.18) | 0.003 | 1.88 (1.22–2.89) | 0.004 | |||||

| Clinical + CAC | 0.730 | 0.746 | 0.720 | ||||||

| Age | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.007 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.04 | 1.03 (1.00–1.07) | 0.03 | |||

| Diabetes | 1.76 (1.00–3.10) | 0.04 | |||||||

| Dyspnoea | 1.50 (1.05–2.04) | 0.02 | 1.77 (1.08–2.89) | 0.02 | |||||

| CAC | |||||||||

| 0 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

| 1–99 | 2.75 (1.44–5.27) | 0.002 | 7.83 (1.00–61.12) | 0.04 | 2.11 (1.04–4.27) | 0.03 | |||

| 100–399 | 4.23 (2.19–8.15) | <0.001 | 14.11 (1.84–108.01) | 0.01 | 2.67 (1.22–5.80) | 0.01 | |||

| ≥ 400 | 7.20 (3.80–13.65) | <0.001 | 20.07 (2.63–153.10) | 0.004 | 4.94 (2.31–10.58) | <0.001 | |||

| Clinical + PET-CTA | 0.743 | 0.753 | 0.753 | ||||||

| Age | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | <0.001 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.81 (1.08–3.03) | 0.02 | |||||||

| Dyspnoea | 1.52 (1.11–2.08) | 0.009 | 1.75 (1.13–2.69) | 0.01 | |||||

| PET-CT findings | |||||||||

| No CAD | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Non-obstructive CAD | 3.36 (1.78–6.37) | <0.001 | 2.24 (0.64–7.80) | 0.2 | 3.63 (1.83–7.20) | <0.001 | |||

| Obstructive CAD, normal sMBF | 3.85 (1.97–7.52) | <0.001 | 4.37 (1.26–15.11) | 0.02 | 2.99 (1.40–6.38) | 0.005 | |||

| Obstructive CAD, abnormal sMBF | 5.84 (3.04–11.21) | <0.001 | 5.61 (1.69–18.57) | 0.005 | 4.99 (2.33–10.70) | <0.001 | |||

The models are adjusted for significant clinical factors, CAC scores, and PET-CTA findings separately.

HR for age is per 1 year. P-values for comparing AUC values between models (clinical + CAC and clinical + PET-CTA) were 0.477 for all patients, 0.625 for men and 0.394 for women.

CAD, coronary artery disease; CAC, coronary calcium; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; sMBF, stress myocardial blood flow.

Coronary calcification was an independent predictor of events after adjustment for age, clinical risk factors, and symptoms both in women and men (Tables 2 and 3). Extensive coronary calcification (CAC score ≥400) predicted events with an adjusted hazard ratio of 20.07 (95%CI 2.63–153.10) in men and 4.94 (95%CI 2.31–10.58) in women, when compared to patients without coronary calcification (CAC score 0).

Table 2.

Univariable predictors of adverse events (all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina pectoris) in all patients, men and women

| All patients | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.39 (1.04–1.86) | 0.02 | ||||

| DM | 1.68 (1.18–2.40) | 0.004 | 2.17 (1.37–3.43) | <0.001 | 1.13 (0.63–2.04) | 0.6 |

| Hypertension | 1.86 (1.36–2.56) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.33–3.35) | 0.001 | 1.64 (1.07–2.54) | 0.02 |

| Smoking | 1.23 (0.91–1.66) | 0.1 | 1.32 (0.87–1.99) | 0.1 | 0.98 (0.61–1.57) | 0.9 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.97 (0.72–1.32) | 0.8 | 1.07 (0.69–1.64) | 0.7 | 0.90 (0.59–1.38) | 0.6 |

| Typical chest pain | 1.52 (1.09–2.14) | 0.01 | 2.00 (1.25–3.20) | 0.004 | 1.21 (0.74–1.96) | 0.4 |

| Any chest pain | 0.88 (0.63–1.24) | 0.4 | 0.90 (0.56–1.42) | 0.6 | 0.94 (0.56–1.56) | 0.8 |

| Dyspnoea | 1.88 (1.41–2.52) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.11–2.56) | 0.01 | 2.31 (1.51–3.53) | <0.001 |

| CAC | ||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 1–99 | 3.23 (1.74–6.01) | <0.001 | 11.52 (1.50–88.10) | 0.01 | 2.68 (1.35–5.32) | <0.001 |

| 100–399 | 5.42 (2.92–10.06) | <0.001 | 23.24 (3.12–172.92) | 0.002 | 3.73 (1.77–7.85) | <0.001 |

| ≥400 | 10.11 (5.61–18.23) | <0.001 | 40.48 (5.53–295.91) | <0.001 | 7.20 (3.55–14.59) | <0.001 |

| PET-CTA | ||||||

| No CAD | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Non-obstructive CAD | 4.57 (2.55–8.19) | <0.001 | 4.21 (1.24–14.30) | 0.02 | 5.17 (2.65–10.09) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive CAD, normal sMBF | 6.01 (3.28–11.03) | <0.001 | 9.30 (2.76–31.31) | <0.001 | 4.75 (2.29–9.87) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive CAD, abnormal sMBF | 10.01 (5.63–17.79) | <0.001 | 13.56 (4.22–43.52) | <0.001 | 8.04 (3.85–16.80) | <0.001 |

HR for age is per 1 year.

CAC, coronary artery calcium, CAD, coronary artery disease, CI, confidence interval, DM, diabetes mellitus, HR, hazard ratio.

Findings of PET-CTA were predictors of events after adjusting for age, clinical risk factors, and symptoms both in women and men (Table 3). As compared to patients with normal coronary arteries, the presence of abnormal sMBF predicted events with an adjusted hazard ratio of 5.61 (95%CI 1.69–18.57) in men and 4.99 (95%CI 2.33–10.70) in women. Non-obstructive CAD predicted adverse events in women, but the effect was statistically non-significant in men (Table 3).

Based on Cox proportional hazards models, there was no significant interaction between sex and either coronary calcification or combined coronary CTA and PET findings (P = 0.4, and P = 0.2, respectively) in predicting adverse events. Similarly, based on the ROC analyses the prognostic value of adjusted coronary artery calcification or combined coronary CTA and PET to predict composite outcome was similar in males and females (P = 0.687 and P = 0.999, Figure 3 and Supplementary data online, Figure S2). Overall, coronary calcification and findings of coronary CTA and PET predicted events equally (P = 0.477).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showing no difference in the performance of coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (P = 0.687) (A) or combined coronary CTA and 15O-water PET (P = 0.999) (B) in predicting composite end-point of death, non-fatal MI or UAP between men and women. Analyses were adjusted for age, hypertension, and symptom status (typical angina and dyspnoea).

Figure 4 shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence of the composite events that were significantly different (P > 0.001) according to the extent of CAC and findings of PET-CTA in both men and women. Overall, the event rate was higher in men than women (Log-rank P = 0.02) with the annual adverse event rate being 1.37% in the whole cohort, 1.65% in men, and 1.17% in women.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing the occurrence of death, non-fatal MI or UAP according to coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (A and C) or combined coronary CTA and 15O-water PET (B and D) in women (A and B) and men (C and D).

Discussion

This study compared the findings and prognostic value of combined coronary CTA and PET myocardial perfusion imaging between women and men referred to diagnostic testing for suspected obstructive CAD. The main finding of our study is that coronary CTA combined with 15O-water PET myocardial perfusion imaging predicts adverse events equally well in both women and men.

Our results are in line with recent studies showing that among patients evaluated for suspected CAD, men have more coronary atherosclerosis, a higher prevalence of obstructive CAD, and lower event-free survival than women.4,5,6 Unlike some recent analyses,4,16 our results do not show differences in referral for ICA or early invasive management between women and men with myocardial ischaemia. The observed revascularization rate is in line with previous studies.11 Although we do not have data on medical management and adherence to preventive therapies, our results suggest that the higher event rate in men is due to more extensive CAD.

Risk stratification is an important goal of diagnostic testing for CAD. Previous analyses have pointed out that there is limited data on differences in the prognostic value of noninvasive diagnostic tests for CAD, particularly coronary CTA, according to sex.1 More recently, retrospective studies have reported equal predictive value of per vessel extent of CAD by coronary CTA in women and men.17 In the Scottish Computed Tomography of the Heart (SCOT-HEART) trial, the addition of coronary CTA to a standard evaluation of patients with chest pain showed similar benefits in women and men.5 In the Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE) trial, women appeared to derive even more prognostic information from CTA than men who tend to derive similar prognostic value from both anatomical and functional tests.18 Our results are in line with these previous studies demonstrating the prognostic value of a diagnostic strategy based on initial coronary CTA in both women and men.

The finding that CAC and non-obstructive CAD were predictive of events is consistent with the prognostic significance of atherosclerotic plaque.19 In a subgroup of patients in whom obstructive CAD was excluded by coronary CTA alone, the presence of non-obstructive CAD was associated with an increased event rate only in women. However, the number of patients was relatively small and the degree of atherosclerosis was small (77% of patients having CAC score <100) in this subgroup.

Combined or hybrid imaging enables the evaluation of both coronary anatomy by CTA and the detection of myocardial ischaemia by perfusion imaging. Previous evidence supports the diagnostic and prognostic value of SPECT perfusion imaging in women and men.1,3,20,21 Studies have also reported the similar prognostic value of myocardial perfusion abnormalities detected by 82Rb or 13N-ammonia PET perfusion imaging in women and men.20,21 Instead, there is limited evidence on the prognostic value of hybrid imaging. Two studies have shown that in patients with intermediate coronary lesions, evidence of ischaemia is associated with an increased event risk after hybrid imaging.10,22 However, possible differences in the prognostic value of combined imaging between women and men have remained unexplored. Our study included a large cohort of patients evaluated for suspected obstructive CAD by coronary CTA followed by 15O-water PET. Instead of all patients, stress MBF was evaluated by 15O-water PET in 657 patients (45% women) who had suspected stenosis detected by coronary CTA. 15O-water PET showed abnormal sMBF more often in men than in women (63% vs. 36%). Abnormal sMBF was associated with an increased risk of death, MI, or UAP in both women and men (HR 5.0 and 5.6, respectively). Our study extends previous findings in that there was no interaction between sex and the prognostic value of imaging findings based on a hybrid imaging strategy using coronary CTA combined with selective PET perfusion imaging.

Study limitations

Our study is associated with all limitations of retrospective analysis in a cohort where imaging findings were reported to treating physicians. Previous studies suggest differences in the intensity of secondary prevention in men and women,4,16 but in this retrospective study, it was not feasible to evaluate changes in medication after imaging. Furthermore, since results of laboratory tests were available for a limited number of patients, some potentially relevant prognostic factors, such as anaemia, blood cholesterol or glucose levels, or renal dysfunction could not be included in the analyses. We defined abnormal perfusion as any segment with sMBF below the ischaemic threshold based on previous studies showing the predictive value of this parameter.12,23 The severity and extent of perfusion abnormalities may add prognostic information, but thresholds have not been established for 15O-water PET23,24 and our patient cohort was small for subgroup analyses. Reduced coronary flow reserve (CFR) has been associated with an excess risk of cardiovascular events in the absence of obstructive CAD, particularly in women.25,26 In our patient cohort, PET perfusion imaging was performed only for evaluation of haemodynamic significance of suspected obstructive lesions on coronary CTA and instead of CFR, only sMBF was assessed.12 Therefore, microvascular dysfunction in the absence of epicardial CAD as well as reduced CFR despite preserved sMBF remains undetected. However, we have previously published that the frequency of pure microvascular dysfunction is low in a similar cohort as in this study.27 Our study provides novel prognostic information about hybrid or combined imaging in women and men evaluated for suspected CAD.

Conclusion

Combined anatomical and functional imaging shows more often normal coronary anatomy and less frequently ischaemic CAD in women than in men. Women have a lower rate of adverse events including death, MI, or UAP, after diagnostic testing. Findings of coronary CTA combined with PET myocardial perfusion imaging independently predict adverse events equally in women and men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by grants from the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, and State Research Funding of Turku University Hospital.

Contributor Information

Iida Kujala, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland.

Wail Nammas, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland; Heart Center, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Hämeentie 11, FI-20520 Turku, Finland.

Teemu Maaniitty, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland; Department of clinical physiology, nuclear medicine and PET, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland.

Iida Stenström, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland; Heart Center, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Hämeentie 11, FI-20520 Turku, Finland.

Riku Klén, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland.

Jeroen J Bax, Heart Center, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Hämeentie 11, FI-20520 Turku, Finland; Department of Cardiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Juhani Knuuti, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland; Department of clinical physiology, nuclear medicine and PET, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland.

Antti Saraste, Turku PET Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 4-8, FI-20520 Turku, Finland; Heart Center, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Hämeentie 11, FI-20520 Turku, Finland.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Dolor RJ, Patel MR, Melloni C, Chatterjee R, McBroom AJ, Musty MDet al. Noninvasive Technologies for the Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease in Women. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 58. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haase R, Schlattmann P, Gueret P, Andreini D, Pontone G, Alkadhi Het al. Diagnosis of obstructive coronary artery disease using computed tomography angiography in patients with stable chest pain depending on clinical probability and in clinically important subgroups: meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ 2019;365:I1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mieres JH, Gulati M, Bairey Merz N, Berman DS, Gerber TC, Hayes SNet al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected ischemic heart disease: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;130:350–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pagidipati NJ, Hemal K, Coles A, Mark DB, Dolor RJ, Pellikka PAet al. Sex differences in functional and CT angiography testing in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2607–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mangion K, Adamson PD, Williams MC, Hunter A, Pawade T, Shah ASet al. Sex associations and computed tomography coronary angiography-guided management in patients with stable chest pain. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1337–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lubbers M, Coenen A, Bruning T, Galema T, Akkerhuis J, Krenning Bet al. Sex differences in the performance of cardiac computed tomography compared with functional testing in evaluating stable chest pain. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:e005295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kajander S, Joutsiniemi E, Saraste M, Pietilä M, Ukkonen H, Saraste Aet al. Cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging accurately detects anatomically and functionally significant coronary artery disease. Circulation 2010;122:603–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rizvi A, Han D, Danad I, Hartaigh BÓ, Lee JH, Gransar Het al. Diagnostic performance of hybrid cardiac imaging methods for assessment of obstructive coronary artery disease compared with stand-alone coronary computed tomography angiography: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:589–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano Cet al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2020;41:407–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maaniitty T, Stenström I, Bax JJ, Uusitalo V, Ukkonen H, Kajander Set al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography with selective PET perfusion imaging in coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:1361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stenström I, Maaniitty T, Uusitalo V, Ukkonen H, Kajander S, Mäki Met al. Absolute stress myocardial blood flow after coronary CT angiography guides referral to invasive angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:2266–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danad I, Uusitalo V, Kero T, Saraste A, Raijmakers PG, Lammertsma AAet al. Quantitative assessment of myocardial perfusion in the detection of significant coronary artery disease: cutoff values and diagnostic accuracy of quantitative [(15)O]H2O PET imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1464–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blanche P, Dartigues J, Jacqmin-Gadda H. Estimating and comparing time-dependent areas under receiver operating characteristic curves for censored event times with competing risks. Stat Med 2013;32:5381–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez Jet al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2011;12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walli-Attaei M, Joseph P, Rosengren A, Chow CK, Rangarajan S, Lear SAet al. Variations between women and men in risk factors, treatments, cardiovascular disease incidence, and death in 27 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;396:97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schulman-Marcus J, Hartaigh BÓ, Gransar H, Lin F, Valenti V, Cho Iet al. Sex-Specific associations between coronary artery plaque extent and risk of Major adverse cardiovascular events: the CONFIRM long-term registry. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pagidipati NJ, Coles A, Hemal K, Lee KL, Dolor RJ, Pellikka PAet al. Sex differences in management and outcomes of patients with stable symptoms suggestive of coronary artery disease: insights from the PROMISE trial. Am Heart J 2019;208:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams MC, Moss AJ, Dweck M, Adamson PD, Alam S, Hunter Aet al. Coronary artery plaque characteristics associated with adverse outcomes in the SCOT-HEART study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gebhard C, Fiechter M, Herzog BA, Lohmann C, Bengs S, Treyer Vet al. Sex differences in the long-term prognostic value of 13N-ammonia myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45:1964–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kay J, Dorbala S, Goyal A, Fazel R, Di Carli MF, Einstein AJet al. Influence of sex on risk stratification with stress myocardial perfusion rb-82 positron emission tomography: results from the PET (positron emission tomography) prognosis multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1866–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pazhenkottil AP, Nkoulou RN, Ghadri JR, Herzog BA, Buechel RR, Küest SMet al. Prognostic value of cardiac hybrid imaging integrating single-photon emission computed tomography with coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harjulahti E, Maaniitty T, Nammas W, Stenström I, Biancari F, Bax JJet al. Global and segmental absolute stress myocardial blood flow in prediction of cardiac events: [15O] water positron emission tomography study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021;48:1434–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Diemen PA, Wijmenga JT, Driessen RS, Bom MJ, Schumacher SP, Stuijfzand WJet al. Defining the prognostic value of [15O]H2O positron emission tomography-derived myocardial ischaemic burden. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;22:638–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taqueti VR, Shaw LJ, Cook NR, Murthy VL, Shah NR, Foster CRet al. Excess cardiovascular risk in women relative to men referred for coronary angiography is associated with severely impaired coronary flow reserve, not obstructive disease. Circulation 2017;135:566–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gupta A, Taqueti VR, van de Hoef TP, Bajaj NS, Bravo PE, Murthy LVet al. Integrated noninvasive physiological assessment of coronary circulatory function and impact on cardiovascular mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation 2017;136:2325–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stenström I, Maaniitty T, Uusitalo V, Pietilä M, Ukkonen H, Kajander Set al. Frequency and angiographic characteristics of coronary microvascular dysfunction in stable angina: a hybrid imaging study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;18:1206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.