Abstract

Background

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and dementia are associated and comorbid with obesity. However, according to emerging research, the role of obesity in the association between ACEs and dementia seems controversial.

Aims

This analysis aimed to explore the associations between ACEs and different dementia subtypes and the effect modification of long-term body mass index (BMI).

Methods

Data were obtained from the US Health and Retirement Study. Six ACEs were categorised as 0, 1 and 2 or more. All-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias were defined by self-reported or proxy-reported physician diagnosis. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to explore the associations of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias from 2010 to 2020. Effect modification of BMI in 2010 and BMI transition and trajectory (fitted by group-based trajectory modelling) from 2004 to 2010 were assessed.

Results

15 282 participants with a mean age of 67.0 years (58.0–75.0) were included in the 2010 data analysis. Significant interactions of ACEs with baseline BMI, BMI transition and BMI trajectory in their associations with new-onset all-cause dementia and AD were observed (all p<0.05). For instance, positive associations of two or more ACEs (vs none) with all-cause dementia and AD were found in those with a BMI trajectory of maintaining ≥30 kg/m2 (maintain obesity) rather than a decline to or maintaining <25 kg/m2 (decline to or maintain normal weight), with hazard ratios (HRs) of 1.87 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.45 to 2.42) and 1.85 (95% CI: 1.22 to 2.80), respectively.

Conclusions

ACEs were associated with dementia and AD in US adults with long-term abnormally elevated BMI but not with long-term normal or decreasing BMI. Integrated weight management throughout life could prevent dementia among those with childhood adversity.

Keywords: psychiatry, mother-child relations, father-child relations, trauma and stressor related disorders, geriatric psychiatry

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and dementia are commonly comorbid with obesity. Recent evidence has indicated controversial associations between ACEs and later-life obesity and complex associations between long-term body mass index (BMI) and dementia. In this context, it would appear controversial to consider obesity as an intermediary factor connecting ACEs and dementia. Further exploration of the effect modification of long-term BMI between ACEs and dementia subtypes could find ways to alleviate the dementia risk attributed to ACEs, but related evidence remains limited.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study provides evidence for exploring the effect modification rather than the mediating role of long-term BMI in the health impairments of ACEs. The significant interactions between ACEs and long-term BMI in the associations with all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but not other dementias, are found in this study. The positive associations of ACEs with all-cause dementia and AD are more pronounced in older adults with long-term abnormal weight.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Given the enormous dementia burden attributed to obesity in older US adults, our findings underscore the importance of integrated weight management throughout life, considering the impact of stressful events, such as childhood adversity, in preventing dementia.

Introduction

With the population ageing, dementia has become a severe public health concern and is now the leading cause of disability in older adults worldwide.1 According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, 57.4 million individuals worldwide have been affected by dementia—with a forecast of 152.8 million by 20502—imposing heavy financial and medical burdens on patients, families and society. Given that there are various subtypes of dementia with distinct pathological mechanisms, it is crucial to investigate the risk factors specific to each subtype.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) refer to a wide range of traumatic events occurring during childhood or adolescence that can contribute to poor health consequences throughout life.3 4 ACEs are particularly considered substantial risk factors for psychiatric disorders, such as dementia, in older US adults.5 6 Identifying potential moderators of ACEs can therefore benefit those vulnerable to dementia. Emerging evidence has identified some moderators of the psychiatric hazards attributed to ACEs, such as physical inactivity and binge drinking.7 8 These moderators, on the other hand, are significantly associated with obesity.9 10

Interestingly, ACEs and dementia are commonly comorbid with metabolic disorders like obesity.11 ACEs and obesity share comparable behavioural or biological concerns, such as sleep disorders and excessive inflammatory levels, both of which raise the risk of dementia, especially in men.12–16 Conversely, ACEs are widely considered upstream factors for obesity.17 Thus, obesity seems to play a mediating role in the causal chain between ACEs and dementia. However, recent evidence has indicated inverse associations between ACEs and later-life obesity,18 rendering the role of obesity controversial. Compared with mediators, effect modification (also interpreted as moderators or moderated effects) focuses more on the interaction with exposure and does not exist in the causal chain between exposure and outcome. A study based on adults in the UK explored the interactions between childhood maltreatment and obesity toward mental disorders and behavioural problems,7 suggesting that exploring the effect modification of body mass index (BMI) in the association of ACEs and dementia may provide new perspectives. However, this UK study only used baseline BMI to define obesity. Given the emerging evidence that compared adults with stable BMI to those with declining BMI, who are more likely to develop cognitive impairment or dementia,19 20 the interactions of ACEs and longitudinal changes in BMI, that is, BMI transition and trajectory, also need to be explored.

To fill this knowledge gap, we prospectively evaluated the effect modification of BMI, BMI transition and BMI trajectory in the associations of ACEs with all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias among middle-aged and older adults in a US national cohort study.

Methods

Study population

Data were from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative cohort that included community-dwelling Americans over the age of 50 years. The baseline survey was conducted in 1992, with every 2-year follow-ups including a wide range of socioeconomic and health information. When respondents were unable to complete the survey on their own, proxies were used. The HRS was supported by the National Institute on Aging (U01AG009740).21 22 All participants provided written informed consent and detailed information that can be found at https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products/restricted-data/available-products/11516. In this secondary analysis study, we used the HRS 2010 as the baseline, with follow-ups until 2020. Longitudinal data on BMI were from the HRS 2004–2010.

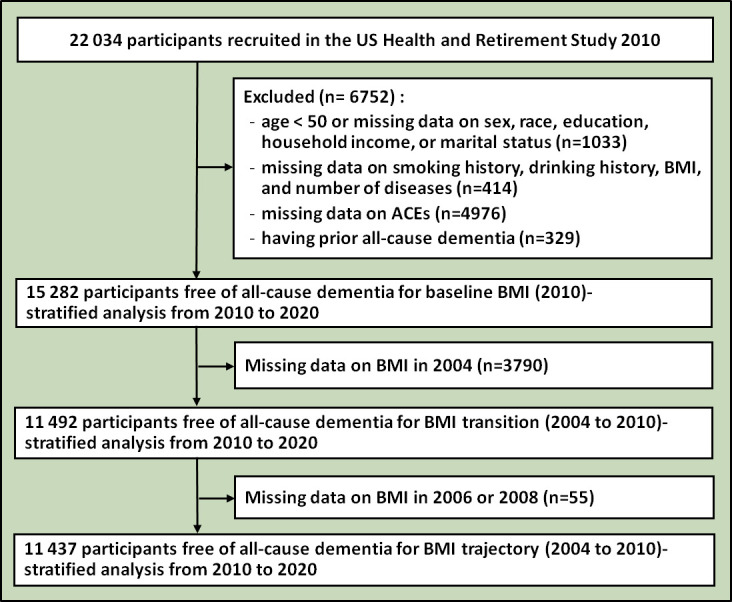

The study flowchart is shown in figure 1. Of the 22 034 participants recruited in 2010, those who were aged <50 years or had missing data on sex, race, education, household income or marital status (n=1033); who had missing data on smoking history, drinking history, BMI or number of diseases (n=414); who had missing data on ACEs (n=4976); and who had prior all-cause dementia (n=329) were excluded, leaving 15 282 participants. Of these, those with missing data on BMI in 2004 (n=3790) were excluded in the BMI transition-stratified analysis, while those with missing data on BMI in 2006 or 2008 (n=55) were further excluded in the BMI trajectory-stratified analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participation. ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; BMI, body mass index.

Definition of ACEs

The detailed definitions of ACEs are shown in online supplemental table 1. In the HRS, since 2006, the Psychosocial and Lifestyle Questionnaires (PLQ) was used to assess ACEs before the age of 18 years.23 The PLQ included these four items: (1) Did you have to do a year of school over again?; (2) Did either of your parents drink or use drugs so often that it caused problems in the family?; (3) Were you ever physically abused by either of your parents? and (4) Were you ever in trouble with the police? The first three were interviewed from 2006 to 2012, while the last question was asked from 2008 to 2012. According to previous research, we included two events regarding emotional neglect and economic adversity in childhood.24 All ACEs were then dichotomised and summed, with values ranging from 0 to 6. ACEs were categorised as 0, 1, and 2 or more.

gpsych-2023-101092supp001.pdf (137KB, pdf)

Assessment of BMI, BMI transition and BMI trajectory

In this study, BMI in 2006, 2008 and 2010 was first obtained from measurements by health professionals, and missing values were imputed using self-reported BMI. BMI in 2004 was obtained from self-report only.25 Participants were then classified as normal weight, overweight and obesity according to a BMI of <25 kg/m2, 25≤BMI<30 kg/m2 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively.26

BMI transition was identified using the BMI status in 2004 and 2010. Given the need to include adequate cases of dementia in each analytical group, we finally identified seven BMI transition patterns in this study: maintain obesity, maintain overweight, obesity to overweight, overweight to obesity, maintain normal weight, normal to abnormal weight (overweight or obesity) and abnormal to normal weight.

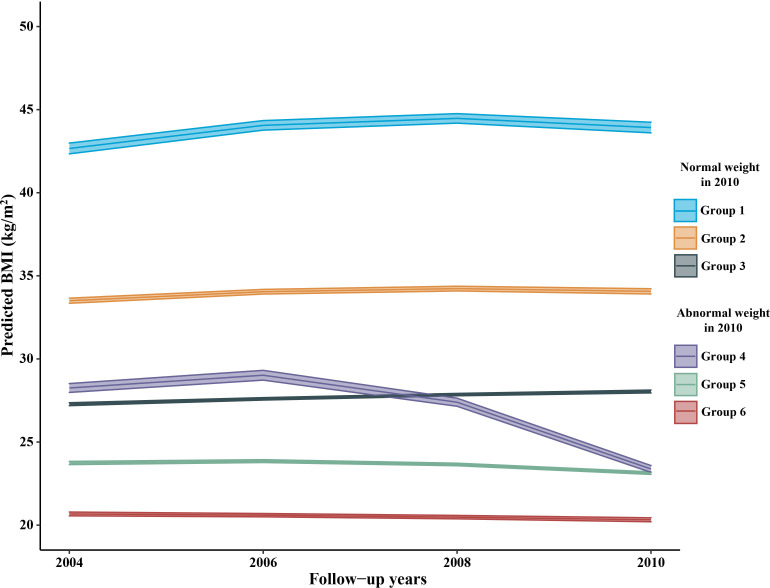

BMI trajectory was identified using the BMI in 2004 and 2010, as well as in 2006 or 2008. Group-based trajectory modelling was used to fit different BMI trajectories in participants with normal (<25 kg/m2) and abnormal (≥25 kg/m2) baseline BMI, respectively. Lower Bayesian information criteria, lower Akaike’s information criterion and higher entropy indicate better models. Finally, the three-class group was selected in both participants with normal and abnormal baseline BMI (online supplemental table 2 and figure 2). Given the shared clinical significance among the chosen BMI trajectory groups, four BMI trajectory patterns were finally identified: maintain obesity, maintain overweight, decline to normal weight and maintain normal weight.

Figure 2.

Body mass index (BMI) trajectory during 2004–2010 in participants with normal and abnormal BMI in 2010. In participants with abnormal weight in 2010, groups 1 and 2 refer to ‘maintain obesity’, while group 3 refers to ‘maintain overweight’. In participants with normal weight in 2010, group 4 refers to ‘decline to normal weight’, while groups 5 and 6 refer to ‘maintain normal weight’.

Definition of all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias

All-cause dementia and AD were diagnosed by physicians and were self-reported or proxy-reported biennially in the HRS from 2010 to 2020 through questionnaires. Those who reported all-cause dementia but not AD were defined as having other dementias.

Definition of cognitive function

The cognitive function in the HRS was measured using a modified version of the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status, which included episodic memory, serial-7 number subtraction questions and counting backward tests.27 Episodic memory was determined by the sum of immediate and delayed word recalls using 10 random words. The serial-7 number subtraction questions referred to five serial subtractions of 7 from 100 (0–5). For the counting backward test, participants had to count backwards from 20 as fast as possible. Scoring was based on consecutive counts on the first attempt (2 points) and successful counts on the second attempt (1 point).

The total cognitive function score ranged from 0 to 27, with a higher score indicating better cognitive function. Subsequently, each 5-year age and educational attainment-stratified means and standard deviations (SDs) of cognitive scores in 2010 were calculated. Corresponding cognitive z scores were calculated as (cognitive scores−means)/SD.

Covariates

Information on age, sex, race, education, household income, marital status, smoking history, drinking history and number of chronic diseases was collected using structured questionnaires biennially. Race was classified as white/Caucasian and black or others. Education was categorised as high school or less and college or above. Household income was divided into tertiles. Marital status was defined as married and single. Smoking and drinking history were classified as ever and never. Chronic diseases included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, heart disease, stroke and psychological diseases, and were divided into 0, 1, and 2 or more.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of included participants were described as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables, and frequency and per cent (%) for categorical variables. To compare characteristics by the number of ACEs, differences in continuous and categorical variables were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 tests.

To explore whether ACEs can result in long-term BMI changes, we examined ACEs’ associations with baseline BMI status, BMI transition and BMI trajectory using multinomial logistic regression. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, household income, marital status, smoking history, drinking history and number of chronic diseases.

The longitudinal associations (hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI)) of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias from 2010 to 2020 were investigated using the Cox proportional hazards models and floating absolute risk. The floating approach allows acceptable comparisons between any two exposure groups, decreasing undesired correlation between coefficients.28–30 Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, residence, education, household income and marital status. Model 2 was further adjusted for smoking history, drinking history and the number of chronic diseases based on model 1. Model 3 was further adjusted for baseline BMI based on model 2. In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded cognitively abnormal participants (cognitive z scores of <−1.5) at baseline. The interaction analysis based on the multiplicative term of ACEs and BMI, as well as the baseline BMI (normal, overweight and obesity)-stratified analyses, were further conducted. Sex-stratified analyses were also performed to deal with sex differences.

The BMI transition-stratified and the BMI trajectory-stratified longitudinal associations of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias were also investigated using the Cox proportional hazards models and floating absolute risk. The stepwise adjustments were made as those used in the baseline BMI-stratified analyses. P values for the interaction between ACEs and the BMI transition/trajectory were measured using the multiplicative term of ACEs and BMI transition/trajectory.

This study was reported under Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.31 Analyses were performed using SAS (V.9.4, SAS Institute) and R statistical software V.4.2.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing). All analyses were two-sided, and p<0.05 or 95% CI that did not cross 1.00 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the participants included are shown in table 1. A total of 15 282 participants (41.8% men) with a mean age of 67.0 years (58.0–75.0) without prior dementia at baseline were included, of whom 1087 developed all-cause dementia (412 cases of AD and 675 cases of other dementias) during the 10 years of follow-up. Among them, 8509 (55.7%) participants self-reported having at least one ACE at baseline, of whom 3615 (23.7%) had two or more ACEs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants included at baseline (N=15 282)

| Characteristics | Number of ACEs | χ 2 | p value | ||

| 0 (n=6773) | 1 (n=4894) | 2 or more (n=3615) | |||

| Age, years | 68.0 (59.0–76.0) | 68.0 (59.0–76.0) | 64.0 (57.0–73.0) | 159.40 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 84.82 | <0.001 | |||

| Men | 2564 (37.9) | 2152 (44.0) | 1679 (46.4) | ||

| Women | 4209 (62.1) | 2742 (56.0) | 1936 (53.6) | ||

| Race | 97.38 | <0.001 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 5515 (81.4) | 3689 (75.4) | 2677 (74.1) | ||

| Black or others | 1258 (18.6) | 1205 (24.6) | 938 (25.9) | ||

| Education | 285.95 | <0.001 | |||

| High school or less | 3014 (44.5) | 2741 (56.0) | 2183 (60.4) | ||

| College or above | 3759 (55.5) | 2153 (44.0) | 1432 (39.6) | ||

| Household income | 101.50 | <0.001 | |||

| Bottom tertile | 2024 (29.9) | 1737 (35.5) | 1328 (36.7) | ||

| Middle tertile | 2221 (32.8) | 1652 (33.8) | 1216 (33.6) | ||

| Top tertile | 2528 (37.3) | 1505 (30.8) | 1071 (29.6) | ||

| Marital status | 1.29 | 0.525 | |||

| Married | 4425 (65.3) | 3171 (64.8) | 2322 (64.2) | ||

| Single | 2348 (34.7) | 1723 (35.2) | 1293 (35.8) | ||

| Smoking history | 171.22 | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 3289 (48.6) | 2076 (42.4) | 1277 (35.3) | ||

| Ever | 3484 (51.4) | 2818 (57.6) | 2338 (64.7) | ||

| Drinking history | 26.97 | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 2800 (41.3) | 2213 (45.2) | 1659 (45.9) | ||

| Ever | 3973 (58.7) | 2681 (54.8) | 1956 (54.1) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.3 (23.9–31.1) | 27.5 (24.5–31.6) | 28.3 (25.0–32.5) | 109.10 | <0.001 |

| Number of chronic diseases | 86.12 | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 1155 (17.1) | 673 (13.8) | 444 (12.3) | ||

| 1 | 1737 (25.6) | 1150 (23.5) | 798 (22.1) | ||

| 2 or more | 3881 (57.3) | 3071 (62.8) | 2373 (65.6) | ||

| New-onset all-cause dementia | 6.34 | 0.042 | |||

| Yes | 442 (6.5) | 371 (7.6) | 274 (7.6) | ||

| No or censored | 6331 (93.5) | 4523 (92.4) | 3341 (92.4) | ||

| New-onset AD | 1.40 | 0.498 | |||

| Yes | 182 (2.7) | 141 (2.9) | 89 (2.5) | ||

| No or censored | 6591 (97.3) | 4753 (97.1) | 3526 (97.5) | ||

| New-onset other dementias | 10.49 | 0.005 | |||

| Yes | 260 (3.8) | 230 (4.7) | 185 (5.1) | ||

| No or censored | 6513 (96.2) | 4664 (95.3) | 3430 (94.9) | ||

Values are presented as number (n) with percentage (%) or medians with IQRs.

Bolded refers to statistically significant.

ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

As shown in online supplemental table 3, more ACEs (vs none) are not significantly associated with baseline obesity or long-term abnormal weight in older US adults. Thus, there is insufficient evidence that ACEs can result in abnormal weight in older US adults or that abnormal weight is in the causal chain between ACEs and dementia, which further provides evidence for our exploration of the effect modification of long-term abnormal weight rather than its mediating role in the associations between ACEs and all-cause dementia.

Participants with one and two or more ACEs were at a significantly higher risk of developing new-onset all-cause dementia (fully adjusted HRs of 1.14 (95% CI: 1.03 to 1.26) and 1.36 (95% CI: 1.20 to 1.53)) and other dementias (fully adjusted HRs of 1.21 (95% CI: 1.07 to 1.38) and 1.55 (95% CI: 1.34 to 1.80)), but not AD (fully adjusted HRs of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.86 to 1.20) and 1.07 (95% CI: 0.87 to 1.32)) when compared with those with no ACEs (online supplemental table 4). Sex-stratified analysis showed similar findings. The findings of sensitivity analysis in cognitively normal participants aligned with our main results (online supplemental table 5).

Table 2 indicates significant interactions between ACEs and baseline BMI in their associations with new-onset all-cause dementia and AD (p<0.05). Among the overweight and obesity groups, but not the normal weight group, two or more ACEs (vs none) were positively associated with new-onset all-cause dementia, with fully adjusted HRs of 1.68 (95% CI: 1.38 to 2.05) and 1.54 (95% CI: 1.25 to 1.89), respectively. The positive association between two or more ACEs and new-onset AD was only found in the obesity group (fully adjusted HRs=1.41, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.98). Furthermore, ACEs were associated with new-onset other dementias in participants who were overweight or obesity. The sex-stratified analysis indicated that the positive associations of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia and AD in the overweight and obesity groups were more substantial in men (online supplemental table 6).

Table 2.

Baseline BMI-stratified longitudinal associations of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias: Cox proportional hazards regression

| Number of ACEs | Cases/number of participants | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

| All-cause dementia: p for interaction between ACEs and baseline BMI=0.003 | ||||

| Normal weight (BMI <25 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 217/2193 | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.15) | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.15) | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.15) |

| 1 | 140/1337 | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.27) | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.26) | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.26) |

| 2 or more | 77/883 | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.28) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.26) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.26) |

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 128/2449 | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.20) | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.20) | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.20) |

| 1 | 142/1887 | 1.31 (1.11 to 1.54) | 1.30 (1.11 to 1.53) | 1.30 (1.10 to 1.53) |

| 2 or more | 104/1301 | 1.73 (1.42 to 2.10) | 1.69 (1.38 to 2.05) | 1.68 (1.38 to 2.05) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 97/2131 | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.26) | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.22) | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.22) |

| 1 | 89/1670 | 1.14 (0.93 to 1.41) | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.39) | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.39) |

| 2 or more | 93/1431 | 1.56 (1.27 to 1.92) | 1.53 (1.24 to 1.89) | 1.54 (1.25 to 1.89) |

| AD: p for interaction between ACEs and baseline BMI=0.008 | ||||

| Normal weight (BMI <25 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 93/2193 | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.24) | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.24) | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.24) |

| 1 | 57/1337 | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.30) | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.31) | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.31) |

| 2 or more | 20/883 | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) | 0.65 (0.42 to 1.01) | 0.65 (0.42 to 1.01) |

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 50/2449 | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.33) | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.33) | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.33) |

| 1 | 53/1887 | 1.15 (0.88 to 1.51) | 1.16 (0.88 to 1.51) | 1.16 (0.88 to 1.51) |

| 2 or more | 34/1301 | 1.32 (0.94 to 1.85) | 1.34 (0.95 to 1.88) | 1.34 (0.95 to 1.88) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 39/2131 | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.38) | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.38) | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.38) |

| 1 | 31/1670 | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.38) | 0.96 (0.68 to 1.36) | 0.96 (0.67 to 1.36) |

| 2 or more | 35/1431 | 1.44 (1.03 to 2.02) | 1.41 (1.00 to 1.97) | 1.41 (1.01 to 1.98) |

| Other dementias: p for interaction between ACEs and baseline BMI=0.139 | ||||

| Normal weight (BMI <25 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 124/2193 | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.22) | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.22) | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.22) |

| 1 | 83/1337 | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.38) | 1.10 (0.89 to 1.36) | 1.10 (0.89 to 1.36) |

| 2 or more | 57/883 | 1.33 (1.02 to 1.73) | 1.29 (0.99 to 1.67) | 1.28 (0.98 to 1.67) |

| Overweight (25≤BMI<30 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 78/2449 | 1.00 (0.80 to 1.26) | 1.00 (0.80 to 1.26) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.26) |

| 1 | 89/1887 | 1.40 (1.14 to 1.72) | 1.38 (1.12 to 1.69) | 1.37 (1.12 to 1.69) |

| 2 or more | 70/1301 | 1.97 (1.55 to 2.49) | 1.87 (1.47 to 2.38) | 1.87 (1.47 to 2.37) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | ||||

| 0 | 58/2131 | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) |

| 1 | 58/1670 | 1.26 (0.97 to 1.63) | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.61) | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.62) |

| 2 or more | 58/1431 | 1.63 (1.25 to 2.12) | 1.60 (1.23 to 2.08) | 1.60 (1.23 to 2.08) |

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race, education, household income and marital status. Model 2 was further adjusted for smoking history, drinking history and number of chronic diseases based on model 1. Model 3 was further adjusted for baseline BMI based on model 2.

Bolded refers to statistically significant.

ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; AD, Alzheimer's disease; BMI, body mass index.

Significant interactions between ACEs and BMI transition toward all-cause dementia and AD, but not other dementias, are shown in online supplemental table 7. Two or more ACEs (vs none) were significantly associated with new-onset all-cause dementia in the maintain obesity, maintain overweight and obesity to overweight groups, with fully adjusted HRs of 1.78 (95% CI: 1.37 to 2.31), 1.94 (95% CI: 1.51 to 2.50) and 1.76 (95% CI: 1.03 to 3.00), respectively. Certain significant associations between ACEs and new-onset AD and other dementias were also found in groups with abnormal BMI transition. However, in the abnormal to normal weight group, two or more ACEs (vs none) are negatively associated with new-onset AD (HR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.90).

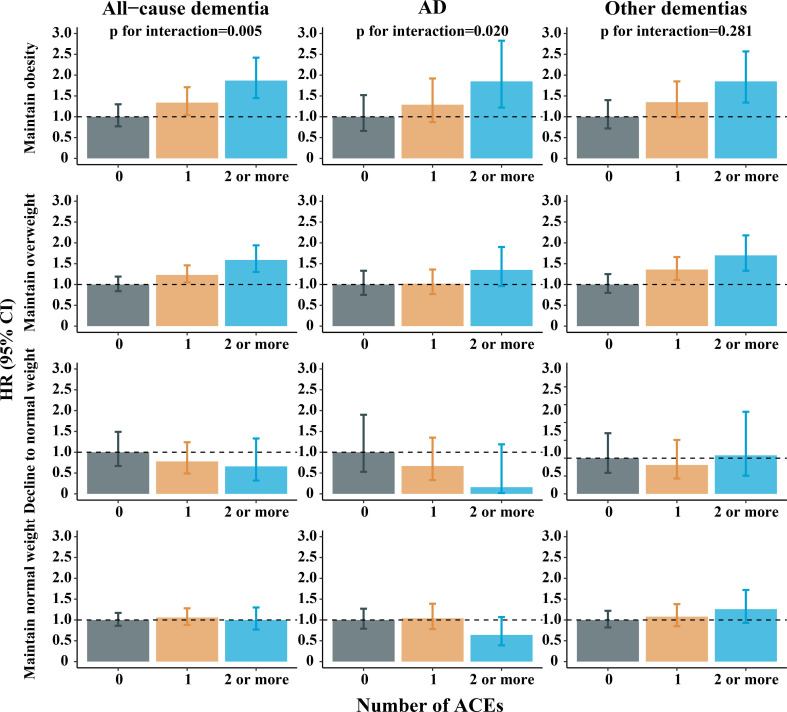

Figure 3 and online supplemental table 8 show significant interactions between ACEs and the BMI trajectory in their associations with new-onset all-cause dementia and AD (p<0.05), but not other dementias. Participants with one and two or more ACEs (vs none) were at higher risk of developing all-cause dementia in the maintain obesity and maintain overweight groups (fully adjusted HRs of 1.34 (95% CI: 1.04 to 1.71) and 1.23 (95% CI: 1.05 to 1.46) for one ACE, and 1.87 (95% CI: 1.45 to 2.42) and 1.59 (95% CI: 1.30 to 1.94) for two or more ACEs, respectively). Compared with no ACEs, positive associations between two or more ACEs and new-onset AD in the maintain obesity group and between two or more ACEs and new-onset other dementias in the maintain obesity and maintain overweight groups were also found.

Figure 3.

Fully adjusted BMI trajectory-stratified longitudinal associations of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias. Models were adjusted for age, sex, residence, education, household income, marital status, smoking history, drinking history, number of chronic diseases and baseline BMI. P for interaction indicates the p value for interaction between ACEs and BMI trajectory. ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

Main findings

This study found significant moderated effects of baseline BMI, BMI transition and BMI trajectory in the positive associations of ACEs with new-onset all-cause dementia and AD. More specifically, ACEs were significantly associated with new-onset all-cause dementia in participants with long-term overweight and obesity but not with long-term normal weight or decline to normal weight. For AD, a significant association with ACEs was found in those with long-term obesity.

Our findings confirm previous conclusions that more ACEs are associated with a higher risk of new-onset all-cause dementia and its subtypes. Though ACEs are known to increase dementia risk in later life,32 their associations with specific dementia subtypes, such as AD and other dementias, are less explored. According to a recent meta-analysis, only three studies have investigated the associations between ACEs and AD, of which two were conducted in the USA.33 The two US studies, however, were limited due to their inadequacy of ACE types and lack of nationally representative data for the USA.34 35 Furthermore, few researchers have investigated the associations between ACEs and other dementias.

In this study, no significant association between ACEs and new-onset AD was observed in the general US population of men or women. Instead, we found potential positive associations of ACEs with all-cause dementia, AD and other dementias only in older US adults with abnormal long-term BMI. ACEs and obesity are risk factors for dementia and are always comorbid,11 suggesting that ACEs and obesity may share similar pathogenic pathways underlying dementia. A set of metabolic changes after ACEs, such as fat accumulations, elevated insulin resistance and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, increase the risk of later diabetes onset, a significant upstream factor for dementia.11 36–39 Obesity, on the other hand, can significantly promote the positive association between diabetes and dementia,40 41 which may help to interpret the significant and enduring moderated effects of abnormal weight. In addition, ACEs and obesity both contribute to hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation and abnormal programming of stress hormones like cortisol and corticotropin-releasing factor, which over time induce neuron cell death and amyloid burden, thus increasing the risk of dementia and its subtypes.39 42–44 Another potential mechanism is that the increased chronic inflammation associated with ACEs may trigger an amyloid cascade, which, along with diminished cognitive reserve and compounded hippocampal insults/atrophy, may hasten the onset of AD.45 Mental disorders and unhealthy lifestyles associated with increased dementia risk are common consequences of ACEs and obesity and may also play a role in our findings.33 However, the associations of ACEs with AD and other dementias vary widely, underscoring the importance of more comprehensive dementia-specific studies in the future.

Interestingly, we observed that the positive associations of ACEs with dementia and its subtypes were more substantial in men with abnormal weight than in women. The protective role of oestrogen on insulin sensitivity, lipid accumulation and inflammation may help reduce the BMI-promoted positive associations between ACEs and dementia.46 However, given the lack of information on ACE duration and starting age, we should consider these results more seriously.

To the best of our knowledge, this prospective cohort study is the first to investigate whether the associations of ACEs with dementia vary in different dementia subtypes in men and women using a nationally representative US cohort. We indicated that findings of using total dementia as the outcome variable differed significantly from those of dementia subtype-specific analyses, suggesting the significance of differentiating dementia subtypes by pathogenesis. We considered long-term BMI changes (transition and trajectory), thereby preventing biased results by using data from just one point. In addition, the sex-stratified analysis in this study revealed significant sex differences in dementia and its subtypes and ensured the robustness of our conclusions.

According to emerging evidence, obesity is now the leading cause of dementia in older US adults.47 Though recent research has indicated controversial associations between obesity and dementia,19 20 our findings underscore the importance of integrated weight management from a life-course perspective, considering the impact of stressful events, such as childhood adversity, in preventing dementia.

Limitations

Our study remains limited due to several shortcomings. Information on ACEs, dementia and AD was mainly self-reported or gained from proxies, which could cause recall bias. However, earlier research has also employed the corresponding indicators, and our findings are relatively comparable. Furthermore, the number of participants with AD in this study was limited, which may impair our statistical power, especially in the stratified analysis. Studies with more specific dementia subtypes, such as vascular dementia, and more extensive study populations are also required in the future.

Implications

In conclusion, ACEs were positively associated with all-cause dementia and its subtypes in US adults with long-term abnormal BMI but not those with long-term normal or decreasing BMI. Our findings highlight that it is crucial to distinguish different dementia subtypes and emphasise the importance of managing weight from a life-course perspective to prevent dementia.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the efforts made by the original data creators, depositors, copyright holders and funders of the data collections and their contributions to accessing data from the Health and Retirement Study.

Biographies

Ziyang Ren graduated from the School of Public Health at Zhejiang University in China in 2022 with a Bachelor of Medicine degree. He was admitted to the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Peking University in China as a doctoral student in September 2022. His main research interests include neuropsychiatric disorders, social epidemiology, and life course epidemiology.

Binbin Su obtained his PhD degree from the Institute of Population Research at Peking University in China in 2022. Currently, he is undertaking postdoctoral research at Peking Union Medical College in Beijing, China. His primary research interests lie in Geriatric Epidemiology and Environmental Epidemiology. His main research interests include the health implications of population aging and environmental changes and make significant contributions to the improvement of public health.

Footnotes

Contributors: JL and ZR designed the study. ZR managed and analysed the data. ZR and BS prepared the first draft. ZR, BS, YD and TZ reviewed and edited the manuscript, with comments from XZ and JL. All authors were involved in revising the paper. JL accepts full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This study is funded by the Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (21ZDA107).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The deidentified participant data from the Health and Retirement Study can be found at https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/. Related codes are available upon reasonable request to ziyang_ren@bjmu.edu.cn.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants. The HRS was approved by the Institute for Social Research and Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan (IRB protocol: HUM00061128). All participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1. Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:459–80. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022;7:e105–25. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson CA, Scott RD, Bhutta ZA, et al. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ 2020;371:m3048. 10.1136/bmj.m3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e356–66. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schickedanz HB, Jennings LA, Schickedanz A. The association between adverse childhood experiences and positive dementia screen in American older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2022;37:2398–404. 10.1007/s11606-021-07192-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roberts AL, Zafonte R, Chibnik LB, et al. Association of adverse childhood experiences with poor neuropsychiatric health and dementia among former professional US football players. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e223299. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Macpherson JM, Gray SR, Ip P, et al. Child maltreatment and incident mental disorders in middle and older ages: a retrospective UK biobank cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021;11:100224. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Taillieu T, et al. Individual- and relationship-level factors related to better mental health outcomes following child abuse: results from a nationally representative Canadian sample. Can J Psychiatry 2016;61:776–88. 10.1177/0706743716651832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jakicic JM, Powell KE, Campbell WW, et al. Physical activity and the prevention of weight gain in adults: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51:1262–9. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arif AA, Rohrer JE. Patterns of alcohol drinking and its association with obesity: data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. BMC Public Health 2005;5:126. 10.1186/1471-2458-5-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yam KY, Naninck EFG, Abbink MR, et al. Exposure to chronic early-life stress lastingly alters the adipose tissue, the leptin system and changes the vulnerability to western-style diet later in life in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017;77:186–95. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santos M, Burton ET, Cadieux A, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, health behaviors, and associations with obesity among youth in the United States. Behav Med 2022;2022:1–11. 10.1080/08964289.2022.2077294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Irwin MR, Vitiello MV. Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for alzheimer's disease dementia. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:296–306. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30450-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deighton S, Neville A, Pusch D, et al. Biomarkers of adverse childhood experiences: a scoping review. Psychiatry Res 2018;269:719–32. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cox AJ, West NP, Cripps AW. Obesity, inflammation, and the gut microbiota. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:207–15. 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nianogo RA, Rosenwohl-Mack A, Yaffe K, et al. Risk factors associated with alzheimer disease and related dementias by sex and race and ethnicity in the US. JAMA Neurol 2022;79:584–91. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiss DA, Brewerton TD. Adverse childhood experiences and adult obesity: a systematic review of plausible mechanisms and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Physiol Behav 2020;223:112964. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin L, Chen W, Sun W, et al. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and obesity in a developing country: a cross-sectional study among middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:6796. 10.3390/ijerph19116796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li J, Liu C, Ang TFA, et al. BMI decline patterns and relation to dementia risk across four decades of follow-up in the Framingham Study. 2022;19:2520–27. 10.2139/ssrn.4006128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guo J, Wang J, Dove A, et al. Body mass index trajectories preceding incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 2022;79:1180–7. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, et al. Cohort pofile: the health and retirement study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:576–85. 10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fisher GG, Ryan LH. Overview of the health and retirement study and introduction to the special issue. Work Aging Retire 2018;4:1–9. 10.1093/workar/wax032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith J, Ryan L, Fisher G, et al. Psychosocial and lifestyle questionnaire 2006–2016. University of Michigan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grummitt LR, Kreski NT, Kim SG, et al. Association of childhood adversity with morbidity and mortality in US adults: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:1269–78. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen H, Zhou T, Guo J, et al. Association of long-term body weight variability with dementia: a prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2022;77:2116–22. 10.1093/gerona/glab372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khan SS, Ning H, Wilkins JT, et al. Association of body mass index with lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and compression of morbidity. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:280–7. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1988;1:111–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Easton DF, Peto J, Babiker AG. Floating absolute risk: an alternative to relative risk in survival and case-control analysis avoiding an arbitrary reference group. Stat Med 1991;10:1025–35. 10.1002/sim.4780100703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Plummer M. Improved estimates of floating absolute risk. Stat Med 2004;23:93–104. 10.1002/sim.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arbogast PG. Performance of floating absolute risks. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:487–90. 10.1093/aje/kwi221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elm E von, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Short AK, Baram TZ. Early-life adversity and neurological disease: age-old questions and novel answers. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:657–69. 10.1038/s41582-019-0246-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corney KB, West EC, Quirk SE, et al. The relationship between adverse childhood experiences and alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14:831378. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.831378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Norton MC, Smith KR, Østbye T, et al. Early parental death and remarriage of widowed parents as risk factors for alzheimer disease: the cache county study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;19:814–24. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182011b38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Norton MC, Fauth E, Clark CJ, et al. Family member deaths across adulthood predict alzheimer’s disease risk: the cache county study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:256–63. 10.1002/gps.4319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nasca C, Watson-Lin K, Bigio B, et al. Childhood trauma and insulin resistance in patients suffering from depressive disorders. Exp Neurol 2019;315:15–20. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller NE, Lacey RE. Childhood adversity and cardiometabolic biomarkers in mid-adulthood in the 1958 British birth cohort. SSM Popul Health 2022;19:101260. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Biessels GJ, Despa F. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:591–604. 10.1038/s41574-018-0048-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoeijmakers L, Lesuis SL, Krugers H, et al. A preclinical perspective on the enhanced vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease after early-life stress. Neurobiol Stress 2018;8:172–85. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Selman A, Burns S, Reddy AP, et al. The role of obesity and diabetes in dementia. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:9267. 10.3390/ijms23169267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shalev D, Arbuckle MR. Metabolism and memory: obesity, diabetes, and dementia. Biol Psychiatry 2017;82:e81–3. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Epel ES, White ML, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and cortisol activity in obesity: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;62:301–18. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Radford K, Delbaere K, Draper B, et al. Childhood stress and adversity is associated with late-life dementia in aboriginal Australians. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;25:1097–106. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burke SL, O’Driscoll J, Alcide A, et al. Moderating risk of alzheimer’s disease through the use of anxiolytic agents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;32:1312–21. 10.1002/gps.4614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav 2012;106:29–39. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mauvais-Jarvis F, Clegg DJ, Hevener AL. The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Endocr Rev 2013;34:309–38. 10.1210/er.2012-1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Slomski A. Obesity is now the top modifiable dementia risk factor in the US. JAMA 2022;328:10. 10.1001/jama.2022.11058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gpsych-2023-101092supp001.pdf (137KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The deidentified participant data from the Health and Retirement Study can be found at https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/. Related codes are available upon reasonable request to ziyang_ren@bjmu.edu.cn.