Abstract

Introduction

Arthritis and obesity are common co-occurring conditions which can increase disability and risk of adverse outcomes (e.g., total knee replacement).

Methods

We estimated recent obesity trends among adults with arthritis from 2009 to 2014, overall, and by various sociodemographic and health characteristics using data from National Health Interview Survey, an ongoing, nationally representative, in-person household self-reported survey of the noninstitutionalized civilian U.S. A secondary aim was to examine the distribution of body mass index (BMI) categories among adults with and without arthritis.

Results

Obesity prevalence did not change significantly over time among middle-aged and younger adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis either overall (p-trend=0.925 for both groups), or by demographic and health characteristics. Among older adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis the unadjusted obesity prevalence was 29.4% in 2009 and 34.3% in 2014; after adjusting for all demographic and health characteristics there was a significant relative increase in obesity prevalence (15% (95% CI: 6–25)) and over time (p-trend=0.001). The 2014 distribution of BMI categories for adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis (compared with adults without doctor-diagnosed arthritis) was skewed toward the obese category and its subclasses, but there were no significant changes in these relationships from 2009.

Conclusions

Obesity increased significantly over time among older adults with arthritis and remains high when compared with adults without arthritis. Greater dissemination of interventions focused on physical activity and diet are needed to reduce the adverse outcomes associated with obesity and arthritis.

Introduction

Doctor-diagnosed arthritis is a common chronic conditions that affects about 52.5 million adults in the U.S. (22.7% of all adults) and limits the activities of 22.7 million (9.8% of all adults).(1) Obesity affects 36.5% of all adults in the U.S.(2), occurs frequently among those with arthritis(3), and those with both conditions are more likely to have arthritis activity and work limitations(1, 4), be physically inactive(5), report depression and anxiety(6), and have an increased risk of expensive knee replacement.(7)

Weight loss among adults with arthritis has been shown to reduce pain and improve function(8), therefore, losing weight (if obese or overweight) or maintaining a healthy weight are standard intervention recommendations for managing arthritis.

Monitoring trends in obesity among adults with arthritis is important for assessing progress in addressing this risk factor/common comorbid condition. One research study using showed that the prevalence of obesity increased significantly among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis in 14 of 50 states and Puerto Rico from 2003 to 2009(3), but little is known about the national trends in obesity prevalence among adults with arthritis over time.

The primary aim of this study was to estimate recent obesity trends among adults with arthritis during 2009–2014, overall, and by various sociodemographic and health characteristics. A secondary aim was to examine the distribution of body mass index (BMI) categories (underweight, normal, overweight, obese, obese class I, obese class II, and obese class III) among adults with and without arthritis in 2009 and 2014 to determine whether changes were occurring in these categories.

Methods

Study Population

We analyzed the 2009–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an ongoing, nationally representative, in-person household self-reported survey of the noninstitutionalized civilian U.S. population. The NHIS uses a multistage sampling design to collect information on health and other characteristics of individual family members within the household, and supplementary data from one randomly selected “Sample Adult” in the household.(1) Unweighted sample sizes and final response rates were 27,731 (65.4%) in 2009; 27,157 (60.8%) in 2010; 33,014 (66.3%) in 2011; 34,525 (61.2%) in 2012; 34,557 (61.2%) in 2013; and 36,697 (58.9%) in 2014.(1)

Outcome

For our primary aim (obesity trends), we defined obesity as BMI ≥30 kg/m2.(2) For our secondary aim (BMI categories) we defined the following seven BMI categories: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–<25 kg/m2), overweight (25–<30 kg/m2), obese (≥30 kg/m2), as well as obese classes: class I (BMI: 30–<35 kg/m2), class II (BMI: 35–<40 kg/m2), and class III (BMI ≥40 kg/m2).

Arthritis

Doctor-diagnosed arthritis was defined as a “yes” response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?” The arthritis case definition was validated in two prior studies and shown to have sufficient sensitivity and specificity for surveillance purposes.(9, 10)

Other Measurements

Five demographic characteristics were: age group (young adults: 18–44 years, middle-aged adults: 45–64 years, and older adults: ≥65 years), sex, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic other race), education level (<high school, high school, at least some college, completed college or greater), and employment status (employed/self-employed, unemployed, unable to work/disabled, and other). The “other” employment category comprised students, volunteers, homemakers, and retirees.

Five health characteristics were: leisure-time physical activity, self-rated health (very good/excellent, good, and fair/poor), doctor-diagnosed heart disease, doctor-diagnosed diabetes, and serious psychological distress (SPD) (defined by Kessler 6 scale)(11). Leisure-time physical activity was determined from responses to six questions regarding frequency and duration of participation in leisure-time activities of moderate to vigorous intensity and categorized as to whether the participant met the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines(12) for Americans. Total moderate intensity equivalent minutes (moderate minutes + vigorous minutes*2) of physical activity per week were categorized as follows: meeting recommendations (≥150 min per week), insufficient activity (10–149 min), and inactive (<10 min).(13) Adults were considered to have doctor-diagnosed heart disease if they answered “yes” to any of the following four questions: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had coronary heart disease? Angina, also called angina pectoris? A heart attack (also called myocardial infarction? Any kind of heart condition or heart disease (other than the ones I just asked about)?” Adults were considered to have doctor–diagnosed diabetes if they answered “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Adults were considered to have SPD if they had a score of ≥13 on the Kessler scale (0–24).(11)

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were weighted and accounted for the complex multi-stage sampling design. NCHS sampling weights were applied to account for household nonresponse, oversampling of blacks, Hispanics, and Asians, and post-stratification adjustments. (1) Because obesity trends differed by age group, we present age-stratified estimates for the trend analysis.

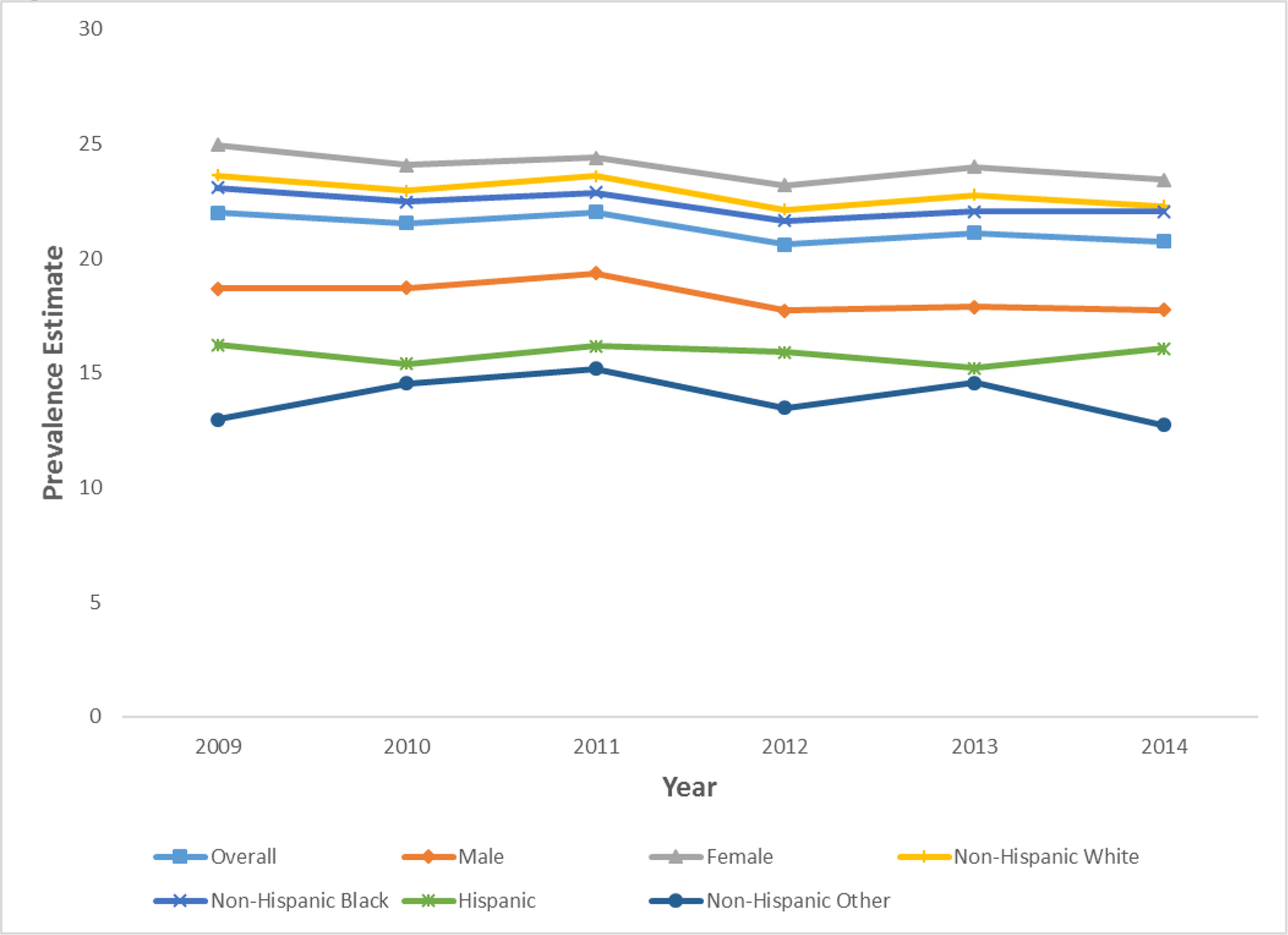

Prior to performing analyses for our study aims, we examined doctor-diagnosed age-standardized arthritis prevalence overall, and by sex, and race, for every year from 2009 to 2014 (Figure 1). In addition, we determined age-standardized obesity prevalence by year for adults with arthritis overall and by sex (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Age-Standardized Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis Prevalence Overall and by Sex and Race/Ethnicity

Figure 2:

Age-Standardized Obesity Prevalence, by Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis Status, Overall and by Sex

For our primary aim, we estimated obesity prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) both overall and by demographic and health characteristics for adults with and without doctor-diagnosed arthritis for the years of 2009 and 2014, and tested for trends in obesity prevalence to see whether obesity changed significantly over time for the years 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014. Estimates not meeting the minimum criterion for precision (relative standard error (RSE) ≤30.0% or a minimum sample size of ≥50) were suppressed, and a test of trend was not performed for a group with at least one suppressed estimate. P-values were generated for trend tests using log binomial regression modeling with obesity as the outcome and the year (2009–2014) as the exposure variable (modeled as a continuous variable) and adjusting for all covariates. In addition, model-adjusted prevalence ratios were also generated from log binomial regression modeling by comparing the average predicted marginal proportions (model-adjusted risks) between the years 2009 (referent) and 2014.

For our secondary aim, we estimated the age-standardized prevalence of the seven BMI categories among adults with and without doctor-diagnosed arthritis in 2009 and 2014. Obesity prevalence estimates were adjusted to the projected 2000 U.S. standard population.(14) A chi-square test of independence with pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were used to determine whether the seven BMI categories differed by doctor-diagnosed arthritis status (yes or no) (Figure 1). Because there were 21 comparisons (7*6/2=21), the Bonferroni-adjusted p-value was (0.05/21)=0.0024.

Obesity increased among older adults with arthritis, so to better understand in which groups of older adults this is occurring in, we performed a stratified analysis among the young-old (65–74 years) and the middle-old (75–84 years) and the old-old (≥85 years).(15)

Results

From 2009 to 2014, the age-standardized prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis ranged from 20.6 in 2012 to 22.0 in 2009 (Figure 1). Women, non-Hispanic whites, and non-Hispanic blacks, were the subgroups with the highest age-standardized prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis. From 2009 to 2014, the age-standardized prevalence of obesity among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis ranged from 40.3% in 2014 to 42.6% in 2013, and prevalence estimates were comparable by sex (Figure 2). For adults without doctor-diagnosed arthritis, the age-standardized prevalence ranged from 24.1 in 2009 to 26.3% in 2014.

Estimates for our primary aim can be found in Table 1. Obesity prevalence did not change significantly over time among middle-aged and younger adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis either overall (p-trend=0.925 for both groups), or among groups defined by demographic and health characteristics.

Table 1:

Trends in unadjusted and adjusted weighted prevalence of obesity* among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis†, overall and by demographic and health characteristics for three age groups--- National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2009 –2014

| Age 18–44 years | Age 45–64 years | Age 65 years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

| Demographic and health characteristics | 2009 n=418; Weighted N=3,827,000 | 2014 n=494; Weighted N=3,152,000 | Test of trend§ from 2009–2014 | Test for difference¶ in prevalence between 2009 (ref) and 2014 | 2009 n=1,213; Weighted N=9,914,000 | 2014 n=1,619; Weighted N=9,791,000 | Test of trend§ from 2009–2014 | Test for difference¶ in prevalence between 2009 (ref) and 2014 | 2009 n=812; Weighted N=5,442,000 | 2014 n=1,393; Weighted N=7,183,000 | Test of trend§ from 2009–2014 | Test for difference¶ in prevalence between 2009 (ref) and 2014 |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | P-trend | PR (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | P-trend | PR (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | P-trend | PR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 43.7 (39.4–48.0) | 40.9 (37.0–44.9) | 0.925 | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | 43.4 (40.8–45.9) | 42.7 (40.2 –45.2) | 0.925 | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 29.4 (27.4–31.4 | 34.3 (32.3–36.4) | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Men | 47.7 (40.6–54.9) | 41.5 (35.3 –47.9) | 0.588 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 43.5 (39.6–47.4) | 43.6 (39.7–47.5) | 0.751 | 1.02 (0.91–1.13) | 29.2 (25.9–32.7) | 32.3 (29.1–35.7) | 0.060 | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) |

| Women | 41.0 (35.9–46.4) | 40.4 (35.2–45.8) | 0.473 | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 43.3 (40.0–46.6) | 42.0 (38.9–45.1) | 0.768 | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 29.5 (27.1–32.0) | 35.6 (33.2–38.2) | 0.002 | 1.16 (1.06–1.27) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 41.7 (36.6–47.1) | 37.7 (33.0–42.7) | 0.652 | 1.04 (0.89–1.21) | 40.9 (37.9–43.9) | 40.3 (37.3–43.4) | 0.927 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | 27.9 (25.7–30.1) | 33.6 (31.2–36.1) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.08–1.32) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 55.9 (45.4–65.8) | 54.6 (45.5–63.4) | 0.970 | 1.00 (0.81–1.22) | 54.9 (49.1–60.5 | 53.9 (48.7–59.0) | 0.714 | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 41.8 (36.2–47.5) | 46.8 (41.7–51.9) | 0.206 | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) |

| Hispanic | 46.8 (36.2–57.6) | 55.1 (46.4 –63.5) | 0.877 | 0.98 (0.77–1.25) | 52.3 (44.0–60.4) | 48.1 (40.8–55.5) | 0.767 | 0.97 (0.82–1.16) | 38.7 (31.0–47.0) | 36.7 (30.7–43.1) | 0.288 | 0.90 (0.74–1.10) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | - | - | - | - | ††† | 35.8 (26.0–47.0) | - | - | ††† | ††† | - | - |

| Education Level | ||||||||||||

| < High school diploma | 43.7 (30.7–57.6) | 41.9 (31.8– 52.8) | 0.737 | 1.05 (0.77–1.43) | 52.9 (46.8–59.0) | 50.0 (44.1–55.9) | 0.855 | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) | 32.9 (29.4–36.7) | 36.3 (31.9–40.9) | 0.078 | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) |

| High school diploma | 48.0 (40.6–55.5) | 43.5 (35.8–51.5) | 0.793 | 0.97 (0.80–1.19) | 45.7 (41.3–50.2) | 46.3 (42.0–50.7) | 0.562 | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) | 30.2 (26.7–34.0) | 34.3 (30.6–38.2 | 0.133 | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) |

| At least some college | 41.1 (33.1–49.6) | 47.0 (39.0–55.1) | 0.382 | 1.11 (0.88–1.39) | 46.2 (40.6–51.9) | 46.0 (41.0–51.0) | 0.584 | 0.96 (0.84–1.10) | 29.8 (24.0–36.3) | 35.1 (30.7–39.8) | 0.064 | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) |

| Completed college or greater | 41.7 (34.8–49.0) | 34.2 (27.5–41.5) | 0.681 | 0.96 (0.77–1.19) | 35.7 (31.9–39.7) | 35.9 (32.3–39.6) | 0.656 | 0.98 (0.87–1.09) | 25.2 (21.4–29.5) | 32.9 (29.4–36.6) | 0.067 | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) |

| Employment Status | ||||||||||||

| Employed/self-employed | 42.9 (37.5–48.4) | 40.7 (35.7–45.9) | 0.782 | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) | 40.5 (37.0–44.0) | 41.1 (37.7–44.5) | 0.604 | 1.02 (0.94–1.12) | 34.9 (29.1–41.3) | 36.8 (31.2–42.7) | 0.705 | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) |

| Unemployed | 42.3 (30.6–55.0) | 40.4 (27.6–54.6) | 0.792 | 1.05 (0.73–1.52) | 39.4 (29.9–49.8) | 40.3 (31.5–49.9) | 0.847 | 1.03 (0.78–1.35) | 44.6 (24.8–66.2) | 41.9 (25.7–59.9) | 0.655 | 0.86 (0.45–1.66) |

| Unable to work/disabled | 53.0 (40.3–65.3) | 44.5 (35.3–54.0) | 0.755 | 0.96 (0.75–1.24) | 51.9 (47.3–56.5) | 49.1 (44.6–53.5) | 0.023 | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) | 46.9 (38.5–55.5) | 51.2 (43.7–58.6) | 0.425 | 1.08 (0.89–1.31) |

| Other†† | 35.4 (24.9–47.4) | 37.4 (26.4 –49.8) | 0.608 | 0.91 (0.63–1.31) | 43.6 (37.5–49.8) | 39.2 (33.6–45.1) | 0.285 | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 26.9 (24.8–29.2) | 32.3 (30.1–34.6) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) |

| Physical activity ** | ||||||||||||

| Meeting recommendations | 37.3 (32.0–43.0) | 37.8 (32.6–43.4) | 0.876 | 0.99 (0.83–1.18) | 32.4 (28.7–36.4) | 33.6 (30.1–37.2) | 0.258 | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) | 23.4 (19.8–27.4) | 26.9 (23.7–30.4) | 0.032 | 1.21 (1.02–1.44) |

| Insufficient activity | 46.5 (36.7–56.5) | 45.5 (34.7–56.7) | 0.814 | 1.03 (0.80–1.33) | 46.1 (41.0–51.3) | 46.5 (40.5–52.6) | 0.814 | 1.02 (0.89–1.16) | 29.0 (24.6–33.8) | 37.5 (33.1–42.2) | 0.057 | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) |

| Inactive | 50.2 (43.0–57.4) | 43.8 (36.7–51.3) | 0.931 | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) | 53.0 (49.0–57.0) | 50.5 (46.8–54.2) | 0.147 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 32.9 (30.1–36.0) | 38.7 (35.6–41.8) | 0.032 | 1.12 (1.01–1.23) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||

| Very good/excellent | 35.1 (29.3–41.3) | 34.3 (28.6 –40.5) | 0.882 | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 29.4 (26.1–33.0) | 31.3 (27.8–34.9) | 0.264 | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) | 23.5 (20.2–27.1) | 29.3 (26.1–32.7) | 0.004 | 1.25 (1.07–1.45) |

| Good | 53.3 (46.0–60.5) | 47.2 (39.0 –55.5) | 0.897 | 0.99 (0.82–1.20) | 50.0 (45.5–54.5) | 46.9 (42.1–51.7) | 0.693 | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 29.9 (26.3–33.8) | 34.5 (30.9–38.2) | 0.157 | 1.11 (0.96–1.27) |

| Fair/poor | 47.1 (37.6–56.7) | 46.2 (38.7–53.8) | 0.623 | 1.06 (0.85–1.31) | 54.8 (50.3–59.1) | 52.2 (48.0–56.3) | 0.412 | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 35.4 (31.7–39.3) | 41.5 (37.9–45.2) | 0.041 | 1.12 (1.00–1.24) |

| Heart Disease §§ | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 45.9 (32.0–60.3) | 37.3 (25.3–51.1) | 0.233 | 0.82 (0.60–1.13) | 47.6 (42.2–53.0) | 49.0 (44.2–53.9) | 0.370 | 1.05 (0.94–1.17) | 29.7 (26.6–33.1) | 35.7 (32.4–39.2) | 0.010 | 1.18 (1.04–1.33) |

| No | 43.4 (39.0–47.8) | 41.4 (37.3–45.6) | 0.558 | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 41.9 (39.1–44.8) | 41.1 (38.4–44.0) | 0.614 | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | 29.1 (26.5–31.7) | 33.6 (31.2–36.0) | 0.013 | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) |

| Diabetes ¶¶ | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 71.2 (54.6–83.6) | 59.2 (44.4– 72.6) | 0.243 | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) | 71.5 (65.8–76.5) | 68.5 (63.7–73.0) | 0.651 | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 48.7 (44.3–53.1) | 49.2 (44.7–53.8) | 0.859 | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) |

| No | 41.0 (36.5–45.5) | 39.5 (35.5–43.7) | 0.755 | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | 36.9 (34.3–39.6) | 36.9 (34.2–39.6) | 0.942 | 1.00 (0.93–1.09) | 23.7 (21.6–26.0) | 29.4 (27.4–31.6) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.12–1.37) |

| SPD *** | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 52.1 (38.6–65.4) | 39.8 (28.0–53.1) | 0.405 | 0.87 (0.64–1.20) | 48.2 (39.6–56.9) | 47.4 (40.6–54.3) | 0.472 | 0.93 (0.77–1.13) | 30.3 (21.5–40.9) | 46.8 (35.3–58.7) | 0.336 | 1.19 (0.84–1.68) |

| No | 42.5 (38.1–47.0) | 40.5 (36.3–44.9) | 0.756 | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | 42.9 (40.3–45.7) | 42.4 (39.8–45.1) | 0.932 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 29.5 (27.4–31.6) | 34.1 (32.0–36.4) | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) |

Abbreviation: N=Weighted sample size, n=sample size, CI = confidence interval, SPD=serious psychological distress

Obesity was defined as a body mass index (weight [kg] / height [m2]) ≥30.0.

Doctor–diagnosed arthritis was defined as a “yes” response to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?

P-value estimated for trend analysis for all the available years from 2009 to2014 by using time as a continuous variable in a log-binomial regression model and adjusting for all other demographic and health characteristics shown in the table.

Prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% CIs estimated from a log-binomial regression model after adjusting for all other demographic and health characteristics to test the difference in prevalence from 2009 (reference) to 2014.

Determined from responses to six questions regarding frequency and duration of participation in leisure–time activities of moderate or vigorous intensity and categorized according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Total minutes (moderate to vigorous) of physical activity per week were categorized as follows: meeting recommendations (≥150 min per week), insufficient activity (10–<150 min), and inactive (<10 min).

Students, volunteers, homemakers, and retirees.

Adults were considered to have doctor–diagnosed heart disease if they answered “yes” to any of the following four questions: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had coronary heart disease? Angina, also called angina pectoris? A heart attack (also called myocardial infarction)? Any kind of heart condition or heart disease (other than the ones I just asked about)?”

Adults were considered to have doctor–diagnosed diabetes disease if they answered “yes” to “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?”

Adults were considered to have serious psychological distress (SPD) if they scored ≥13 on the Kessler scale.

Estimate flagged and not shown for not meeting relative standard error (RSE) criterion <30 or sample size<50

Notes: Estimates in boldface indicate statistically significant findings.

For older adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, the overall, unadjusted obesity prevalence was 29.4% in 2009 and 34.3% in 2014; after adjusting for all demographic and health characteristics, there was a significant relative increase in obesity prevalence (test for difference 15% (95% CI: 6–25)) between those two years. There was also a significant increase among older adults over the 6 years from 2009 to 2014 (adjusted p-trend=0.001). Among older adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, obesity prevalence increased significantly (adjusted p-trend<0.05) over the six years among women, whites, those who were inactive or met physical activity recommendations, the “other” employed category, both adults who report very good/excellent health and those who report poor/fair health, those with and without heart disease, those without diabetes, and those without SPD. For the stratified analyses among older adults with arthritis, the unadjusted obesity prevalence was 37.9% in 2009 and 39.6% in 2014 for the young-old; 23.0% in 2009 and 30.5% for the middle-old; 13.0% in 2009 and 19.4% in 2014 for the old-old. Obesity increased significantly among the middle-old, and old-old (adjusted p-trend<0.01 for both groups), but not the young-old.

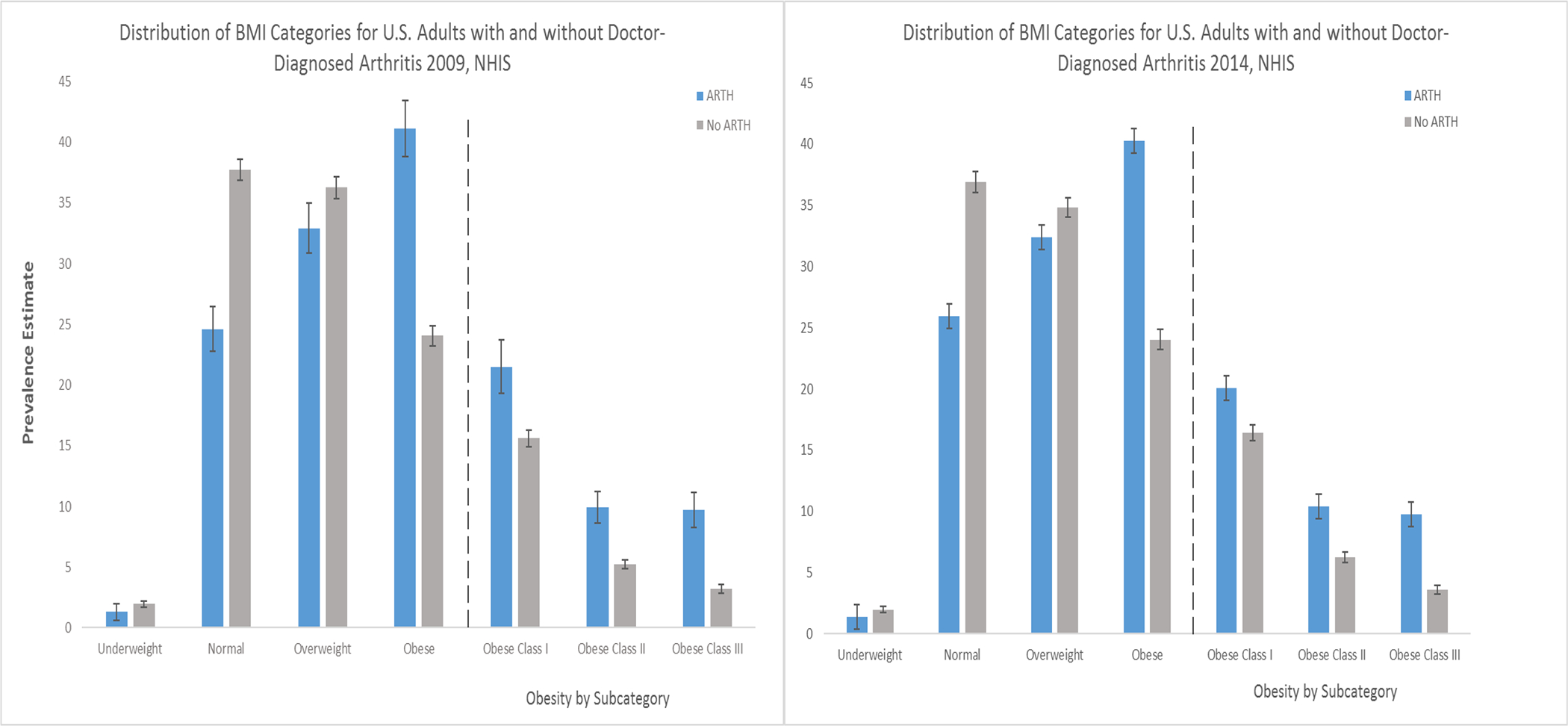

In 2014, the distribution of age-standardized prevalences of BMI categories for adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis (compared with adults without doctor-diagnosed arthritis) was skewed toward the obese category and its subclasses. The age-standardized prevalences of obesity, obesity class I, obesity class II, and obese class III among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis (compared with adults without doctor-diagnosed arthritis) was 40.3% vs. 26.3%, 20.1% vs. 16.4%, 10.4% vs. 6.2%, and 9.8% vs. 3.6% (p-value<0.001 for all 4 comparisons), respectively. (Figure 3). There were no significant changes in these relationships compared with the 2009 values (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Distribution of Seven BMI categories Among Adults with and Without Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis, 2009 and 2014, NHIS

Discussion

Among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, obesity was highly prevalent among all age groups, but obesity trends from 2009 to 2014 showed significant increases only for older adults overall and in several of their demographic and health characteristics categories. This increase in obesity among older adults with doctor-diagnosed occurred primarily in the middle-old (75–84 years) and the old-old (≥85 years); groups with historically lower rates of obesity. Although obesity did not increase significantly for younger and middle-aged adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis in our study, it still remained very high; unadjusted prevalence was 40.9% and 42.7% in 2014, respectively. We found that obesity prevalence was higher (about a 1.5 fold difference) among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis compared with adults without doctor-diagnosed arthritis, and that this difference increased with greater obesity class, but the magnitude of these differences changed little between 2009 and 2014.

The literature examining trends in obesity among adults with arthritis is sparse. A prior report using self-report data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) found that obesity prevalence significantly increased in 14states and Puerto Rico among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis from 2003–2009, whereas most states had no significant change.(3)

The increase in obesity prevalence among older adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis is particularly alarming for several reasons. First, given the aging of the US population that age group is rapidly increasing, with an estimated 72 million (1 in 5 US residents) aged ≥65 years by 2030.(16) Second, the increase in obesity prevalence in older adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis was not limited to only those with poor health characteristics as might be expected, but also occurred among those who reported meeting physical activity recommendations, had very good/excellent health, and did not have heart disease, diabetes, or SPD, suggesting that public health interventions to reduce obesity should focus on all older adults with arthritis, not only those with poor health characteristics. The extensive negative impacts of obesity on health care costs and chronic conditions are well documented.(7, 17–19). Additionally, the prevalence of physical inactivity has been shown to be higher among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis and obesity vs. obesity alone, suggesting that arthritis may be a barrier to physical activity among obese adults.(5) Regular physical activity has been shown to confer a protective effect and prevent many adverse outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and premature death).(20) Improved dietary intake and increased physical activity is needed to curb the increased trend in obesity among older adults with arthritis.

Losing weight for adults with both obesity and arthritis can be difficult, particularly because of the poor function, inactivity, disability, and severe pain that can occur with arthritis. Nonetheless, non-pharmacological strategies such as weight loss have been shown to reduce pain and improve function by lowering joint loading and decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines that affect cartilage degradation in adults with arthritis.(21) A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trial among adults with obesity and arthritis showed that disability could be significantly improved when weight was reduced by over 5.1% for interventions that focus on a combination of diet and exercise, though a large percent of the weight loss is attributable to the diet.(8, 22) The increase in obesity prevalence we observed among older adults with arthritis who met physical activity recommendations emphasizes the need for dietary interventions as well.

Health care counseling of patients with arthritis to lose weight and be more physically active has been linked to healthy behaviors such as attempts to lose weight.(23) One study showed that more than half of adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis have never received provider counseling for weight loss, and only about 11% have taken a self-management education class, and thus, greater counseling and dissemination of self-management interventions are needed.(24) The Guide to Community Preventive Services suggests several approaches to reduce or maintain healthy weight among adults including technology-supported coaching or counseling interventions, and worksite strategies (e.g., improved access to healthy food and opportunities for physical activity).(25) The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening adults for obesity, with provider referral of obese patients to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions (one or more sessions per month for at least 3 months).(26) Developing and strengthening community-clinical linkages (e.g., increasing patient referral by health care practitioners to community programs which disseminate arthritis interventions) is a strategy to address obesity prevention and treatment to reduce the burden of obesity among adults with arthritis.

Our findings are subject to at least two limitations. First, all NHIS variables are collected in-person via self-report and subject to different forms of information bias including, but not limited to, recall bias and social desirability bias. A study from 2001–2006, comparing the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) measured BMI with NHIS self-reported BMI, found that self-reported BMI values >28 were underestimated when compared with measured BMI.(27) Moreover, when comparing measured NHANES and self-reported NHIS obesity estimates from this study, NHIS obesity estimates were about 7 percentage points lower.(27) Therefore, the prevalence of obesity may have been underreported throughout the paper. However, it is not clear that any bias would differ by arthritis status or over the time period examined. Second, small sample sizes for certain subgroups meant that a few estimates were suppressed for not meeting the minimum criterion for precision (RSE ≥30.0%).

Arthritis affects more than 1 in 5 adults(1), and about 40% of adults with arthritis have obesity. Greater dissemination of interventions focused on physical activity and a healthy diet are needed to reduce the adverse outcomes associated with obesity and arthritis. The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation seeks to address obesity via a multi-factorial approach which encompasses health care systems, communities, work sites, and environmental and behavioral changes.(28) For adults with arthritis these factors must address the arthritis-specific barriers to physical activity.(5) This can be accomplished with self-management education and arthritis evidence-based physical activity interventions which have been shown to increase improve reduce pain, and improve function and self-efficacy. (29)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Target Journal: Preventing Chronic Diseases

CDC Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

- 1.Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Theis KA, Murphy LB, Hootman JM, Brady TJ, et al. Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation-United States, 2010–2012. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(44):869–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden C, Carroll M, Fryar C, Flegal K. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS data brief. 2015(219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hootman J Prevalence of obesity among adults with arthritis---United States, 2003−-2009. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2011;60(16):509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theis KA, Murphy L, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Yelin E. Prevalence and correlates of arthritis-attributable work limitation in the US population among persons ages 18–64: 2002 National Health Interview Survey Data. Arthritis Care & Research. 2007;57(3):355–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour K Arthritis as a potential barrier to physical activity among adults with obesity--United States, 2007 and 2009. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2011;60(19):614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy LB, Sacks JJ, Brady TJ, Hootman JM, Chapman DP. Anxiety and depression among US adults with arthritis: prevalence and correlates. Arthritis care & research. 2012;64(7):968–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anandacoomarasamy A, Caterson I, Sambrook P, Fransen M, March L. The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. International journal of obesity. 2008;32(2):211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, Morgan TM, Rejeski WJ, Sevick MA, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50(5):1501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sacks JJ, Harrold LR, Helmick CG, Gurwitz JH, Emani S, Yood RA. Validation of a surveillance case definition for arthritis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2005;32(2):340–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bombard JM, Powell KE, Martin LM, Helmick CG, Wilson WH. Validity and reliability of self-reported arthritis: Georgia senior centers, 2000–2001. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(3):251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-L, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological medicine. 2002;32(06):959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee PAGA. Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report, 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008;2008:A1–H14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Schoenborn CA, Loustalot F. Trend and prevalence estimates based on the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010;39(4):305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA, Statistics NCfH. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected US population. 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zizza CA, Ellison KJ, Wernette CM. Total water intakes of community-living middle-old and oldest-old adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009;64(4):481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The next four decades: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2010.

- 17.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Jama. 1999;282(16):1523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs. 2009;28(5):w822–w31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bray GA, Frühbeck G, Ryan DH, Wilding JP. Management of obesity. The Lancet. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian medical association journal. 2006;174(6):801–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messier SP. Diet and exercise for obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2010;26(3):461–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2007;66(4):433–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehrotra C, Naimi TS, Serdula M, Bolen J, Pearson K. Arthritis, body mass index, and professional advice to lose weight: implications for clinical medicine and public health. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004;27(1):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Do BT, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Brady TJ. Monitoring healthy people 2010 arthritis management objectives: education and clinician counseling for weight loss and exercise. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2011;9(2):136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz DL, O’Connell M, Yeh M-C, Nawaz H, Njike V, Anderson LM, et al. Public health strategies for preventing and controlling overweight and obesity in school and worksite settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, Lux L, Sutton S, Bunton AJ, et al. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;139(11):933–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stommel M, Schoenborn CA. Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001–2006. BMC public health. 2009;9(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamin RM. The Surgeon General’s vision for a healthy and fit nation. Public health reports. 2010;125(4):514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brady TJ, Kruger J, Helmick CG, Callahan LF, Boutaugh ML. Intervention programs for arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(1):44–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]