Abstract

The authors provide an assessment of trends and dynamics of homelessness in Delaware since 2007, when the last systematic study of this topic was released. Using population data on homelessness in the state, the authors present evidence that, after a period of apparent stability, homelessness in Delaware is currently at levels that are unprecedentedly high, while providers of homeless services have not adapted to this change. As a first step to addressing this alarming trend, the authors call for stakeholders to regroup and develop a coordinated, statewide approach to address this problem.

Introduction

The number of people in Delaware who were counted as homeless on a given night doubled between 2020 and 2022.1 Housing Alliance Delaware (HAD), who organizes the annual counts of Delaware’s homeless population, announced it without much fanfare. Media outlets dutifully reported this unprecedented surge. Beyond that there was little response, and assistance for emergency housing was actually cut later in the year. In this essay, we frame this moment, when the response to homelessness in Delaware appears incommensurate to the extent of need, in an historical context that goes back to 2007, when the last systematic assessment of homelessness in Delaware was undertaken. Such an analysis provides insight on how homelessness in Delaware got to this present situation, as well as a basis for how to proceed.

Sixteen years ago, in 2007, University of Delaware’s Center for Community Research and Service (CCRS) released a report titled Homelessness in Delaware: Twenty Years of Data Collection and Research.2 The study looked back to 1987, when CCRS conducted the first study of the extent and nature of homelessness in Delaware. Based upon that and subsequent counts of the state’s homeless population, the CCRS report found there to have been an initial decade of marked increase (from 1986 to 1995), followed by a decade during which the size of the homeless population first dipped and then remained constant. This assessment was a milestone, both because it was the first longitudinal analysis of homelessness in the state, and because, for the first time, data was available to support such an empirically grounded retrospective.

The CCRS report presented a picture of cautious optimism. Homelessness was not getting worse, and, after adjusting for general population growth, was lower than the national rate. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and national advocacy groups, through strategies that targeted “chronically homeless” individuals and called for services enriched permanent housing to supplant shelters, offered means by which to reduce and even eliminate homelessness.3 Finally, local initiatives were falling into place for collecting data, both from comprehensive, single-night counts and from compiling administrative records on shelter and other homeless services, as a means to monitor progress in efforts to reduce homelessness.

After the 2007 CCRS report came a pair of successive reports from the Delaware Interagency Coalition on Homelessness (DICH). DICH was launched in 2005 by Governor Ruth Ann Minner’s executive order, and consisted of representatives from state agencies and key community stakeholders. The reports that DICH issued were plans, ambitiously titled Breaking the Cycle: Delaware’s Ten-Year Plan to End Chronic Homelessness and Reduce Long-Term Homelessness4 (2007) and Delaware’s Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness5 (2013), that built on the belief that homelessness was a problem that could be solved. Both DICH plans laid out roadmaps, but there has been no subsequent examination of how (or even whether) these plans were implemented, or of any impact these plans may have had. Homelessness in Delaware has clearly grown to a scale far greater than what was envisioned by these plans. But beyond that we know little about the interplay between dynamics of the homeless population and the availability of services to house them, both temporarily and permanently.

Assessing Homelessness in Delaware

The 2006 count of Delaware’s homeless population, examined in detail in the 2007 CCRS report, was the first of what has become an annual series of Point in Time (PIT) counts of the homeless population, both in Delaware and nationwide, that continue to this day. The core of the PIT count involves volunteers and outreach workers going to interim housing facilities and to other, non-shelter locations to count people experiencing homelessness. PIT counts are conducted in late January, and results are reported to (and standardized by) HUD.6 For the past 17 years, HUD has issued an Annual Homeless Assessment Report to the US Congress based upon these data and has made these reports and the underlying PIT data available online.7 PIT counts are the means by which the magnitude of homelessness is most commonly assessed, analogous to what the unemployment rate is to labor and the consumer price index is to inflation: imperfect but ubiquitous.

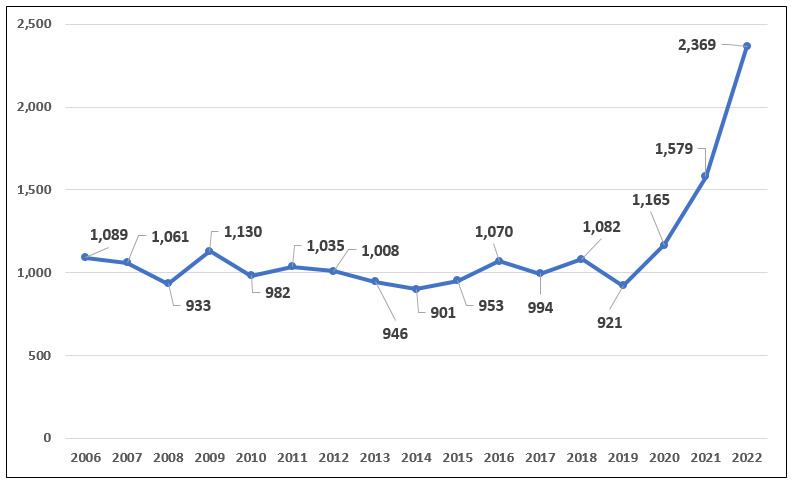

Figure 1 shows the annual size of the homeless population from Delaware’s PIT counts for the years 2006 through 2022.8 We see this series of counts as consisting of two segments. The first segment, starting with the 2006 count of 1,089 homeless people, shows little evidence of sustained increases or decreases for the next 13 years. While the rise in 2009 coincides with the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, overall population changes look to be minor fluctuations more than any clear evidence of sustained increases or decreases. These fluctuations may also have more to do with inconsistencies in the counting process, which is sensitive to weather, numbers of volunteers, and other intangibles unrelated to the actual population size, than to actual changes in the homeless population.

Figure 1.

Total Homeless Population in Delaware8

While Delaware’s PIT count remained largely unchanged, Delaware’s overall population between 2006 and 2018 increased from 864,764 to 973,764, a 12.6 percent increase.9 This means that Delaware’s rate of homelessness, which was 12 per 10,000 people in 2007, dropped to 9.6 per 10,000 in 2019.7 So, while the homeless population size was relatively unchanged, homelessness as a proportion of the overall population declined by about 25 percent over this time. However, homelessness in the US also declined over this period, from 22 to 17 per 10,000.7 This amounted to a 23 percent rate of decline nationally, comparable to Delaware’s rate of decline.

Taken together, in 2019 (as in 2006) Delaware’s level of homelessness remained at the low end of what is “typical” for rates in other US states. Such a consistently low rate more likely reflects Delaware’s relative lack of highly urbanized areas and relatively low housing costs, than how Delaware has responded to homelessness. There is no evidence in Delaware’s homeless population counts that specific programmatic initiatives—like the DICH reports—were linked to systematic decreases in the homeless population.

In abrupt contrast, the second segment of annual Delaware PIT counts shows three consecutive and substantial year-to-year increases. This started with a count of 1,165 in 2020, a 26.5 percent increase and, at the time, Delaware’s highest PIT count ever. This rate of increase was also the highest that year of any state. By comparison, the national PIT count only increased by two percent.10 A closer look shows that Delaware’s increase was across the board – among families and individuals, sheltered and unsheltered, and those newly homeless and with long-term, “chronic” homelessness patterns.11 All this indicates a real increase in Delaware’s homeless population, rather than minor yearly fluctuations.

The 2020 count, conducted in January, preceded the COVID pandemic shutdown, and thus the increase could not be blamed on the pandemic. But additional alarming increases followed into the pandemic, with a 35 percent increase in 2021 and then a 50 percent increase in 2022. The 2022 count was ultimately more than double that of the then-record 2020 count, and in 2022 the homeless rate stood at 23.6 per 10,000. This was now substantially higher than the national rate of 18,12 and more than wiped out the population-adjusted decline that occurred over the thirteen years in the first segment.

Interim Housing Capacity (Shelter, Transitional Housing, and Motel Vouchers)

The increases in the PIT counts in 2021 and 2022 reflected major changes in the way that interim housing was provided in Delaware following the pandemic lockdown. This underscores how the PIT count is influenced not only by the size of the homeless population, but also by the supply of accommodations available to this population.

Interim housing is a term we use to include emergency shelter (EH), transitional housing (TH), seasonal shelter, and hotel/motel vouchers. All are used, in various circumstances, as temporary accommodations for homeless households (both individuals and families). HAD reports data on interim housing capacity to HUD annually in the Housing Inventory Count.13 Up through early 2020, ES and TH were the predominant forms of interim housing in Delaware. After the onset of COVID the majority of households received interim housing through hotel and motel vouchers. This reflects a stunning transformation of service delivery and provides key insights to the homeless population dynamics in the state.

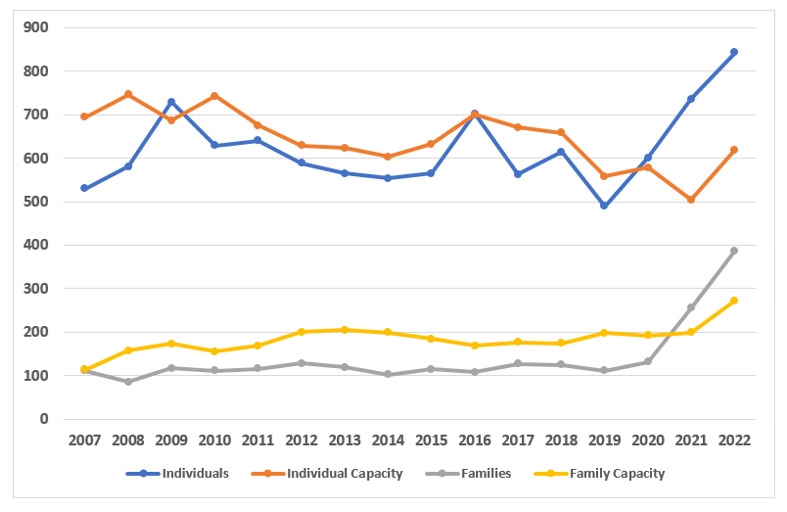

Figure 2 is a time series of Delaware’s combined ES and TH capacity, broken down by family or individual household (i.e., 1-person household). For comparison, Figure 2 also shows the numbers of family and individual households that stayed in interim housing on the night of that year’s PIT count.8 This latter count reflects upwards of 90 percent of those enumerated in the PIT count, as relatively few people are typically counted in unsheltered locations in this count (more on this below). Up through 2019 the supply of ES/TH beds stayed flat for families and declined slightly for individuals, mirroring patterns for the PIT counts of family and individual households, respectively.

Figure 2.

Homeless Individuals and Families and Corresponding Emergency Shelter and Transitional Housing Capacities in Delaware8,13

Figure 2’s pairing of homeless households and available ES/TH accommodations show that when there is a decline in the ES/TH supply, there is a corresponding decrease in the number sheltered. The clearest example of this is in 2019, when the closure of the SafeSpace Delaware (formerly the Rick Van Story Resource Center), following its loss of state funding,14 was mirrored by a drop in the number of individuals in the PIT count. Having fewer shelter beds does not mean that more people resolved their homelessness. It means that there are less beds available for those experiencing homelessness, and those who are unable to get a bed are less likely to be included in the PIT count. Conversely, as happened in 2016, when the interim housing supply expands, those who occupy these additional beds are almost certain to be included in the PIT count.

The gap in most years in which the ES/TH capacity exceeds the occupancy numbers, both in family and individual households, creates the impression that there was no need to expand existing interim housing capacity. In other words, ES/TH supply seemingly stayed flat because no further capacity was needed. The view on the ground was different, however. The vacancies indicated in Figure 2 do not line up with the types of households seeking interim housing for various reasons. For example, vacancies in TH facilities designed for veterans, elderly, or persons with psychiatric disabilities will be unsuitable for those outside of these subpopulations. Thus, the Delaware Center for Homeless Veterans does not accommodate non-veterans, even if they have a vacancy. Geography is also a factor; people in southern Delaware may not be able to travel to northern Delaware, even if there are vacancies. These and other supply and demand mismatches explain why Delaware’s Centralized Intake system, a “one stop” source since 2013 for arranging shelter assignments to most of Delaware’s ES/TH facilities, reported fielding more than 1,100 inquiries in July 2022 from households who were homeless or were having a housing crisis, and were only able to make 213 referrals to available homeless assistance resources.1

A final aspect that warrants further examination concerns 2021 and 2022, when the number of people staying in interim housing vastly exceeded the ES/TH supply. This overflow represents the numbers of households receiving hotel/motel vouchers, a form of interim housing not included in the ES/TH numbers in Figure 2. In Delaware, a limited supply of hotel/motel vouchers have traditionally been available to pay for short term stays when there are no other places for households to stay. The only regular provider of these vouchers is the state’s Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS), which had traditionally provided assistance for up to 50 homeless households at a time who were receiving other state-administered assistance. But with the onset of the COVID pandemic, that changed.

The COVID pandemic wreaked havoc on the provision of interim housing. Most ES and TH facilities, in Delaware and elsewhere, were in congregate settings. This means that, in some facilities, people slept with other individuals and families in large rooms, and, in most facilities, they ate and otherwise spent time with others in common areas. Such arrangements were not conducive to COVID quarantine, thus public health guidelines necessitated that congregate ES/TH facilities cut back on the number of people they accommodated and that they take other measures to limit transmission of COVID. In some cases, facilities had to close outright. Even with these precautions, many were fearful of staying at these facilities and exposing their households to COVID. In response, federal assistance provided funding to states for using hotels and motels, which had rooms sitting empty due to lockdown restrictions, to accommodate households who would otherwise have been faced with going to ES or TH facilities. In Delaware, DHSS administered this hotel/motel voucher assistance.15

This created a situation wherein interim housing suddenly became more desirable and easier to come by. Households that were homeless and/or precariously housed, who otherwise could not or would not have stayed in ES or TH facilities, now applied for and received the DHSS vouchers. As a result, DHSS’s voucher program quickly transformed from its small-scale, short-term pre-pandemic incarnation to administering a voucher program for hundreds of households, both families and individuals, for indefinite periods of time. In 2021, DHSS provided vouchers for 839 people on the night of the PIT count, and in 2022, this number increased further to 1,056.16 At this point, DHSS was Delaware’s largest supplier of interim housing, providing emergency accommodations for more than all the ES and TH facilities combined. Then, in early fall 2022, DHSS scaled back the voucher program to pre-pandemic levels after federal support for this program was no longer available.

The 2021 and 2022 PIT count numbers provide a window into the actual demand for interim housing in Delaware. HAD called it “a crisis laid bare,”11 as it revealed the presence of hundreds of additional individuals and families who were homeless but who otherwise would have been invisible in the PIT count. DHSS data indicated, for example, that the majority of voucher holding families came from Sussex County, the southernmost of Delaware’s three counties that contains a quarter of Delaware’s population and was the most underserved in terms of interim housing until vouchers became available.17 As mentioned earlier, indications are that Delaware’s homeless population was on the increase even before the pandemic due to a tightening supply of affordable housing, and this trend also likely contributed to people receiving DHSS vouchers. However, while the COVID pandemic led to less available EH and TH beds, there is no evidence that it directly led to increased levels of homelessness.

With interim housing capacity and occupancy expanding in tandem to twice its pre-pandemic levels in just two years, Delaware’s interim housing system now lacks the capacity to absorb the actual demand for interim housing in the wake of DHSS’s voucher program rollback. Little is known as to what people, facing homelessness and who otherwise would have applied for vouchers, are now doing. Presumably, they will retreat into a world of makeshift housing arrangements that include sleeping outdoors, in cars, in exploitative or abusive situations, “doubled up” with friends or relatives, or in substandard housing, where only a sliver of them will get included in the PIT count.

Unsheltered Homelessness

In the 2006 PIT count, outreach workers and volunteers fanned out across the state to count people who were homeless and sleeping in unsheltered locations. They counted 213 persons, with the acknowledgement that this count was far from comprehensive. This was the most people that were ever counted in a Delaware PIT count. Subsequent unsheltered counts have been as low as 22 (2011-2012), 10 (2013), and 37 (2014-2015). In 2020 and 2022 the unsheltered counts were at 150 and 154 people,8 respectively, the highest tallies since 2007.

There is no evidence that fluctuations in the unsheltered PIT counts reflect changes in the actual numbers of persons experiencing unsheltered homelessness. A more likely explanation is that resources and conditions particular to individual PIT counts can better explain the drops in unsheltered counts in the early 2010s, and the fluctuations in numbers in other years. Even when the numbers went back up to 150, which paralleled the increases in the overall PIT counts discussed previously, these were likely still substantial undercounts.

The unsheltered portion of the PIT count, in general, is notorious for its methodological limitations.18 Even in a state as small as Delaware, the resources needed to adequately canvas the state far exceed what is available. Even then, the unsheltered homeless population seeks, by default, to be unnoticed, unobtrusive and hidden, often staying in locations that would only be found if their whereabouts were known beforehand. In two tragic illustrations of this, in 2019, four people died from carbon monoxide poisoning while sleeping in a tent with a faulty heater,19 and in 2020 a man, 64 years old, a veteran, and diagnosed with severe mental illness, died of exposure, literally on Main Street, in Newark.20 None of these people were receiving services, and none were included in the PIT count.

Two other counts of homeless subpopulations indicate the magnitude of the Delaware PIT’s undercount of those experiencing homelessness in circumstances other than interim housing. One is a study, included in this issue, of homelessness among people on Delaware’s sex offender registry (SOR).21 People on the SOR are required to report their residence regularly to state police and must check in monthly when they are experiencing homelessness. Their homeless status is noted on their SOR record, which is publicly available online.22 On a night in November 2021, 121 people on the SOR reported homelessness; on a night in February 2023, that number rose to 140. Less than 10 people in each of these counts reported staying in interim housing; indeed, most homeless facilities are off limits to people on the SOR. Thus, the number of people who are homeless (presumably unsheltered) and on the SOR is almost as many as were counted as unsheltered on the 2022 PIT (n=154). Assuming that people on the SOR would constitute, at most, only a modest minority of the unsheltered population, the actual size of the overall unsheltered homeless population in Delaware could easily exceed 400 or 500.

The second count covers a very different population: children and youth enrolled in Delaware’s 19 public school districts who were identified as “homeless” in reports to the US Department of Education (DOE). Over the course of the 2018-2019 academic year, the DOE count had 3,539 students as homeless, with only 122 of these students staying in interim housing. The large majority lived doubled up (2,604) and, by definition, not covered by the PIT count. As the PIT counts increased in subsequent years, the DOE counts dropped to 2,709 (2019-2020) and 2,576 (2020-2021). These decreases were attributed to the added difficulties in identifying homeless students during the COVID pandemic.23 While the PIT counts and the DOE counts are not directly comparable, the DOE count provides a window into how large numbers of homeless and precariously housed families are missed by the PIT count. Presumably, these households who were among those who “appeared” in the 2021 and 2022 PIT counts when hotel/motel vouchers were more available, and will again be uncounted in the PIT count now that these vouchers are scarcer.

Chronic Homelessness and Permanent Supportive Housing

Among the first goals to reducing Delaware’s homeless population was “to adopt and oversee the implementation of a plan to reduce homelessness and end chronic homelessness in Delaware.” DICH’s 2007 plan, Breaking the Cycle, laid out the process to do just that, with the key element consisting of adding 409 new units of permanent supportive housing (PSH) to the existing supply of 277 units.4

PSH, simply put, is the provision of housing that is both affordable and coupled with support services that provide whatever is needed to let the tenant maintain this housing. This housing targets the most difficult to serve among the homeless population, and consistently shows retention rates of around 85 percent.24 This housing is often targeted to people designated as “chronically homeless,” meaning households in which a person has a disabling condition and who has either been continually homeless for a year or more or has had at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three years. In a typical homeless population, less than 20 percent meet the chronic threshold, yet this subpopulation typically consumes upwards of 80 percent of homeless services. Thus, the DICH report asserted that not only would such a near-tripling of Delaware’s PSH supply disproportionately reduce the need for homeless services, but it would also lead to substantial collateral reductions in this group’s use of inpatient hospital, criminal justice and emergency health care services.4

Tracking the progress to attaining the twin goals of an increased statewide PSH supply and a reduced number of people in the homeless population meeting chronic criteria are both possible using HIC data from Delaware that is reported to HUD.11 The benchmark used in the 2007 DICH plan was 297 chronically homeless persons,4 with the goal being to reach zero in ten years by, in part, having 686 PSH units in the state. This housing target was surpassed in 2019, with 724 PSH units dedicated to housing people who had experienced chronic homelessness,11 but there remained 168 people counted in the 2019 PIT count who were considered chronically homeless.8

Following the attainment of this benchmark, the number of PSH units started to decline. By 2022, the number of dedicated units had dwindled back to 420 units.11 Meanwhile, in a manner that reinforces the inverse relationship between PSH supply and numbers of people considered chronically homeless, in 2022 the PIT count enumerated 223 people as chronically homeless, sliding back toward the number cited in 2007.1 This decline in PSH is not a deliberate policy, rather it is partially due to existing projects converting PSH units to more conventional housing, as well as there being difficulty in attracting organizations to develop and manage new PSH housing in Delaware.25 Additionally, the goal in the 2007 DICH report may have been too modest, and an updated assessment is needed to determine the number of PSH units in which the annual turnover in tenants matches the demand for housing from people newly identified as chronically homeless.

Data Collection

The 2007 CCRS report and the 2007 DICH plan both drew heavily on the body of data on Delaware homelessness that was emerging at the time. The CCRS report notes the substantial progress made in two fundamental areas of data collection to guide efforts to reduce homelessness.2 One was establishing the PIT count. The second was the creation of a homeless management information system (DE-HMIS) that systematically collects administrative data compiled by homeless service providers in the state during the course of providing shelter and other services. The DICH plan endorsed the DE-HMIS, and went a step further in stating that “State Departments and Divisions should become users of DE-HMIS, both as the recipients and the providers of data.”4

Seventeen years later, we now have annual PIT count data available for studies, such as this one, which can use it, despite its clear flaws, as a basis for sketching a broader picture of the state of homelessness in Delaware. Getting accurate assessments of the nature and extent of the homeless population is a key first step for better determining the levels and types of resources needed to reduce, and ultimately solve homelessness.

The DE-HMIS, now known as the Community Management Information System (CMIS), also is well-established as a central data repository for administrative records on services provided by homeless service organizations, including shelters, transitional housing programs, PSH providers, outreach programs, and others. As described in the CCRS report, this web-based information system is a powerful means for making the collection of homelessness-related data systematic, accurate and inexpensive.2 Recent studies have combined CMIS data with other data sources to examine connections between homelessness and eviction,26 as well as (in this issue) the costs that homelessness adds to Medicaid expenditures.27

However, the usefulness of the CMIS database is severely restricted by large gaps in the data it collects. One major data hole comes from the refusal of Delaware’s second largest provider of interim housing to share data on their services. A second and larger data hole is the inability of the State of Delaware and HAD, the organization that maintains CMIS, to develop a mechanism by which the State will share with CMIS their data on hotel/motel vouchers. In the wake of the recent expansion of the DHSS voucher program, this has led to a situation where data on homeless services reside in two isolated and incomplete databases, neither of which can be used to draw comprehensive conclusions about homelessness in Delaware at a point when comprehensive data is needed more than ever to address this crisis.17

2023 and Looking Ahead

As this article was going to press, preliminary 2023 PIT count and HIC results became available.28 Overall, the number of people counted as homeless in Delaware on the night of the count was 1,245 people. This number is substantially lower than the overall numbers from the last two PIT counts (see Figure 1), but is still higher than any of the pre-pandemic PIT counts, dating back to the first PIT count in 2006. Similarly, the preliminary 2023 HIC reported a substantial drop in the statewide supply of interim housing (emergency shelter, transitional housing, and hotel/motel vouchers), largely driven by the rollbacks the State made in is hotel/motel voucher program, from 1,056 vouchers on a given night in 2022 to 98 vouchers in 2023.

While this drop in the PIT count will likely be framed as a reduction in the homeless population, our analysis here indicates that cuts in the availability of interim housing better explains this reduced count. In the absence of any signs that poverty has eased or that housing has gotten either more available or less costly over the previous year, a more likely explanation is that, were hotel and motel vouchers as available in 2023 as they were in 2022, there would be no reason to expect any reduction in this year’s PIT count.

Furthermore, in the wake of the reduction in hotel/motel voucher supply, one would expect that more people who otherwise might have received vouchers would be without any housing. The PIT count supports this assumption. Despite the overall drop in the PIT count, the count of the unsheltered homeless subpopulation increased in 2023, from 154 in 2022 to 198. This increase occurred despite a cold, pouring rain that fell on the night of the PIT count, as well as the dismantling of the Milford29 and Georgetown encampments30 earlier that January. In 2022, as many as 100 people lived in unsheltered circumstances in these two sites; places where they could readily be counted last year but stood empty just before this year’s count. That, in spite of these factors, there was such an increase in the unsheltered count this year indicates that actual homelessness has increased while the PIT count has dropped.

Ironically, these contemporary, heightened levels of homelessness coincide with the tenth anniversary of DICH’s ten-year plan to “prevent and end homelessness.”5 More than that, many of the problems called out by the previous reports from DICH and CCRS remain. Instead of visions of chronic homelessness being diminished through an expanded availability of housing for this population, a declining supply of this housing has ushered in the same levels of chronic homelessness seen in 2007. Instead of being at the threshold of a coordinated and comprehensive data collection system, Delaware is still left without the basic tools for getting a systematic accounting of the nature and extent of its homeless population. And, based upon the fragmented data we present here, the size of the unsheltered homeless population conceivably exceeds that of those staying in interim housing.

There have been no statewide initiatives that have addressed homelessness in Delaware since the PIT counts started increasing in 2020. Governor John Carney’s administration has not made any policy pronouncements on homelessness over this period. After using federal funding to massively increase access to hotel/motel vouchers, the State has scaled the program back to pre-COVID levels after federal funding ended. Beyond that, Governor Carney, in his most recent budget address, promoted increased state investments in affordable housing, but asserted that homelessness is “a very different problem” from the housing initiatives he has proposed to fund.31

Delaware’s nonprofit homeless services providers, when faced with the doubling of the homeless population, have stewarded a services system that is largely unchanged from its pre-pandemic structure. Part of this is dictated by the levels of available funding, but there has also been a lack of any stated vision or blueprint about how the homeless services system could better respond to homelessness at its current magnitude. The last time that the Delaware Continuum of Care (CoC), the collective of Delaware’s homeless services providers, assessed the state of homelessness was in 2017 with an action plan called Ending Homelessness in Delaware.32 This action plan laid out specific, systemwide objectives and measures for responding to homelessness, along with a call for the CoC to report back two years later on the progress made toward implementing these objectives and measures. This follow up is now three years past due.

Finally, Delaware lacks an active grassroots advocacy structure focused on homelessness. The recent doubling of the homeless population and subsequent scaling back of services has been met with a conspicuous lack of protest, resistance, or calls for action coming from outside of the homeless services delivery systems. The one piece of legislation in front of the Delaware State Legislature that calls for a substantially different approach to addressing homelessness, the Homeless Bill of Rights (HB 55),33 has a limited backing and little prospect for passage. While Shyanne Miller, an advocate with the H.O.M.E.S. Campaign, acknowledges a need for radical action to end homelessness in Delaware and to fully realize housing as a human right, she also acknowledges the “pervasive silence amongst advocates serving people experiencing homelessness. There’s not enough community outcry and public rejection of austere policies that reduce resources and criminalize people experiencing homelessness.”34

In the absence of a statewide response, the most substantial activities in addressing Delaware’s homelessness are happening on local levels. In 2021, New Castle County, for example, purchased and repurposed a Sheraton hotel into what is now the Hope Center, the largest homeless facility in the state.35 In Georgetown, a partnership between the municipal government and the nonprofit Springboard Collaborative was instrumental in creating a pallet shelter village to provide interim housing to Georgetown’s burgeoning unsheltered homeless population.30 These initiatives both leveraged federal COVID funding to launch these initiatives. In Kent County, the nonprofit organizations Dover Interfaith Housing and Code Purple Kent County are each in initial steps of building new interim housing capacity. While such expansions of capacity are badly needed, they are also ad hoc and not part of a more coordinated response.

A coordinated, statewide response is a critical first step toward addressing what are, based on the data presented here, unprecedented levels of homelessness for Delaware, even after the reductions in the 2023 PIT count results. In 2005, Governor Minner convened DICH to spearhead an effort to end homelessness. In 2007, CCRS’s report set the stage for a very well-attended statewide conference to further assess and act upon homelessness in Delaware. Sixteen years later, a similar convening is again needed to reinvigorate its approach, create an updated plan, and provide a collaborative framework for addressing homelessness. While unity and direction are prerequisite, such a first step will be followed by challenges related to implementation and assessment, given their historical absence in the wake of the plans reviewed here.

In summary, the pandemic has not so much induced waves of new homelessness as exposed deficiencies in how homelessness is being addressed. However, it also presents an opportunity for proceeding in a new manner. Putting these dynamics together creates a situation in which taking action commensurate to the current magnitude of the homelessness problem is critical, lest the problem become even larger and more intractable in the future.

Footnotes

Copyright (c) 2023 Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.Housing Alliance Delaware. (2022). Housing and homelessness in Delaware: 2022. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ugd/9b0471_322d16c2158c4ab09743a897dc12aa6d.pdf

- 2.Peuquet, S. W., Robinson, C. B., & Kotz, R. (2007). Homelessness in Delaware: Twenty years of data collection and research. University of Delaware Center for Community Research and Service and the Homeless Planning Council of Delaware. Retrieved from: https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/2c5d57a8-cad4-495a-bc4a-54fbc9bc6c02/content

- 3.Burt, M. R., Hedderson, J., Zweig, J., Ortiz, M. J., & Aron-Turnham, L. (2004). Strategies for reducjng chronic street homelessness. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/publications/pdf/chronicstrthomeless.pdf

- 4.Delaware Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2007). Breaking the cycle: Delaware’s ten-year plan to end chronic homelessness and reduce long-term homelessness. Delaware State Housing Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.destatehousing.com/FormsAndInformation/Publications/delaware_ten_yr_plan.pdf

- 5.Delaware Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2013). Delaware’s plan to prevent and end homelessness. Delaware State Housing Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.destatehousing.com/FormsAndInformation/Publications/plan_end_homeless.pdf

- 6.Exchange, H. U. D. (2015). Point-in-time count methodology guide. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/4036/point-in-time-count-methodology-guide/

- 7.Exchange, H. U. D. (2023). AHAR Reports. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/ahar/#2022-reports

- 8.Exchange, H. U. D. (2023). CoC homeless populations and subpopulations reports. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/coc-homeless-populations-and-subpopulations-reports/

- 9.The Disaster Center. (2020). Delaware crime rates: 1960-2019. The Disaster Center. Retrieved from: https://www.disastercenter.com/crime/decrime.htm

- 10.Henry, M., de Sousa, T., Roddey, C., Gayen, S., & Bednar, T. J. (2021). The 2020 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- 11.Housing Alliance Delaware. (2020). Housing and homelessness in Delaware: A crisis laid bare. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ugd/9b0471_8c4b0aad6a664d309794565c70e8ff42.pdf

- 12.de Sousa, T., Andrichik, A., Cuellar, M., Marson, J., Prestera, E., & Rush, K. (2022). The 2022 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2022-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- 13.Exchange, H. U. D. (2023). CoC housing inventory count reports. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/coc-housing-inventory-count-reports/

- 14.Kuang, J. (2018, Dec). Most clients placed in temporary housing as 'RVRC' shelter closes for good in Wilmington. Delaware Online/Delaware News Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/local/2018/12/31/wilmington-rvrc-homeless-shelter-safespace-delaware-closes/2449603002/

- 15.Kiefer, P. (2022, May). Number of people experiencing homelessness in Delaware doubled over past two years. Delaware Public Media. Retrieved from: https://www.delawarepublic.org/show/the-green/2022-05-20/number-of-people-experiencing-homelessness-in-delaware-doubled-over-past-two-years

- 16.Housing Alliance Delaware. (2022). Point in time count & housing inventory count: 2022 Report. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ugd/9b0471_b4f4bc93e75c4923a891bc0d33fb4dbd.pdf

- 17.Metraux, S., Solge, J., & Mwangi, O. W. (2021). An overview of family homelessness in Delaware. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ugd/9b0471_b09ebb113aa74d13ae09eba6677523df.pdf

- 18.Lee, T., Leonard, N., & Lowery, L. (2021). Enumerating homelessness: The point-in-time count and data in 2021. The National League of Cities. Retrieved from: https://www.nlc.org/article/2021/02/11/enumerating-homelessness-the-point-in-time-count-and-data-in-2021/

- 19.Hughes, I., & Perez, N. (2020, Feb). 'It's devastating': 4 found dead in tent at homeless camp in Stanton. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2020/02/18/large-police-presence-along-route-7-stanton/4798286002/

- 20.Cassidy, J. (2021, Mar). Homeless Delaware vet honored after being found dead on a cold wintry day in Newark. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2021/03/26/community-comes-together-honor-veteran-edgar-mack/6941492002/

- 21.Metraux, S., & Modeas, A. C. (in press). Homelessness among persons on delaware’s sex offender registry. Delaware Journal of Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delaware State Police, State Bureau of Identification. (n.d.). Delaware sex offender central registry. State of Delaware. Retrieved from: https://sexoffender.dsp.delaware.gov/

- 23.National Center for Homeless Education. (2023). State Pages: Delaware. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://profiles.nche.seiservices.com/StateProfile.aspx?StateID=10

- 24.Cunningham, M., Gourevitch, R., Pergamit, M., Gillespie, S., & Hanson, D. (2018). Denver supportive housing social impact bond initiative: housing stability outcomes. Urban Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99180/denver_supportive_housing_social_impact_bond_initiative_3.pdf

- 25.Kuang, J. (2019, Nov). YMCA ends program that provides 41 beds for Wilmington's homeless. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2019/11/11/wilmington-lose-41-beds-homeless-ymca-plans-end-program/2510678001/

- 26.Metraux, S., Mwangi, O., & McGuire, J. (2022, August 31). Prior evictions among people experiencing homelessness in Delaware. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 8(3), 34–38. 10.32481/djph.2022.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nescott, E. P., Metraux, S., McDuffie, M. J., & Brown, E. (in press). Health & homelessness: Matching Medicaid claims and encounters and the community management information system databases. Delaware Journal of Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Personal Communication. (2023). Housing Alliance Delaware.

- 29.Kiefer, P. (2023, Jan). Residents Milford homeless encampment disperse ahead of final sweep. Delaware Public Media. Retrieved from: https://www.delawarepublic.org/politics-government/2023-01-13/residents-milford-homeless-encampment-disperse-ahead-of-final-sweep

- 30.Kiefer, P. (2023, Jan). Long-awaited Georgetown pallet shelter village welcomes first residents. Delaware Public Media. Retrieved from: https://www.delawarepublic.org/politics-government/2023-01-30/long-awaited-georgetown-pallet-shelter-village-welcomes-first-residents

- 31.Carney, J. (2023). Governor Carney presents FY24 budget. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxCaUQLcYgo (38:35 in video).

- 32.Delaware Continuum of Care. (2017). Ending homelessness in Delaware: Our action plan. Delaware State Housing Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.destatehousing.com/OtherPrograms/othermedia/h4g_action_plan_2017.pdf

- 33.Lynn, S. (2023). House substitute 1 for House Bill 55. Delaware General Assembly. Retrieved from: https://legis.delaware.gov/BillDetail?legislationId=130082

- 34.Miller, S. (2023, Apr 24). H.O.M.E.S. Campaing. Personal communication.

- 35.Kuang, J. (2020, Dec). 'I'm not scared anymore': New Castle County's hotel-turned-homeless shelter gets underway. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2020/12/23/new-castle-countys-hotel-turned-homeless-shelter-housing-73-people/3990700001/