ABSTRACT

Developmental research has attempted to untangle the exact signals that control heart growth and size, with knockout studies in mice identifying pivotal roles for Wnt and Hippo signaling during embryonic and fetal heart growth. Despite this improved understanding, no clinically relevant therapies are yet available to compensate for the loss of functional adult myocardium and the absence of mature cardiomyocyte renewal that underlies cardiomyopathies of multiple origins. It remains of great interest to understand which mechanisms are responsible for the decline in proliferation in adult hearts and to elucidate new strategies for the stimulation of cardiac regeneration. Multiple signaling pathways have been identified that regulate the proliferation of cardiomyocytes in the embryonic heart and appear to be upregulated in postnatal injured hearts. In this Review, we highlight the interaction of signaling pathways in heart development and discuss how this knowledge has been translated into current technologies for cardiomyocyte production.

Keywords: Cardiomyocyte proliferation, Cardiomyocyte production, Heart regeneration, Wnt signaling, Hippo signaling, Embryonic growth pathways, Fetal gene program, hiPSC-CM, Cardiomyocyte self-renewal

Summary: Untangling the drivers of human cardiomyocyte proliferation can stimulate cardiac regenerative approaches. This Review compares in vivo heart growth pathways with the molecular targets promoting in vitro cardiomyocyte proliferation.

Introduction

Heart failure often results from the irreversible loss of functional myocardium or malfunctioning of the individual cardiomyocytes that comprise this tissue (De Boer et al., 2003; Fox et al., 2001; Gerber et al., 2000). This loss of functional cardiomyocytes can be acute or gradual and results in adverse remodeling of the remaining healthy myocardium (Olivetti et al., 1997; Saraste et al., 1997). In turn, myocardial dysfunction results in mechanical stress and upregulation of factors including angiotensin and norepinephrine, which all act to further promote detrimental myocardial remodeling (Colucci, 1997; Adhyapak, 2022). These alterations to extracellular matrix composition, cytoskeletal architecture and cell-cell connections occur in parallel with changes to the cardiac gene profile, such as reinduction of a fetal gene program (Parker et al., 1990; Bray et al., 2008).

Although clinical therapies for heart failure have significantly improved with multiple lines of heart failure drugs and mechanical circulatory support devices (Cook et al., 2015; Mancini and Burkhoff, 2005; Shen et al., 2022; Ponikowski et al., 2016), these treatments do not repair or replace malfunctioning myocardium. A central hurdle is that the adult heart is a largely postmitotic organ, where annual turnover is between 1-2% in young adults, and less than 0.5% in older adults (Bergmann et al., 2009; 2015). Thus, it is unsurprising that the adult heart lacks regenerative capacity post injury. In contrast, before birth, expansion of fetal cardiomyocytes is crucial for proper cardiogenesis and is tightly regulated by Wnt and Hippo signaling, with varying cardiomyocyte proliferation rates depending on location and developmental stage (Drenckhahn et al., 2008; Sturzu et al., 2015; Buikema et al., 2013; Rochais et al., 2009; von Gise et al., 2012; Qyang et al., 2007).

Remarkably, the early postnatal mammalian heart possesses regenerative potential (Haubner et al., 2016), but this regenerative response is lost 1 week after birth and scar tissue is formed in response to injury instead (Porrello et al., 2011; Ye et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018b). Translational cardiology aims to repair or replace a broken heart with autologous material (Laflamme and Murry, 2011; Ptaszek et al., 2012). The advent of patient-specific pluripotent stem cell sources represented a major advance for the field (Burridge et al., 2012), but the generation of large numbers of functional cardiomyocytes remains challenging due to their low proliferative rates (Tani et al., 2022). Here, we review how lessons from in vivo cardiomyocyte proliferation during mammalian cardiac development have been translated into technology to generate cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cell sources.

Lessons from cardiac development

Mesoderm formation

During development, most heart structures arise from the mesodermal germ layer. Mesoderm formation takes place at Carnegie stages (CS) 6-7 in humans and embryonic day (E) 6.5 in mice, at the onset of gastrulation (Zhai et al., 2022). During gastrulation, cells from the blastocyst migrate to give rise to the endoderm and mesoderm. At the end of gastrulation, the three germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm) are specified. At the onset of mesoderm formation, the intraembryonic mesoderm subdivides into four distinct groups: the chordamesoderm, paraxial mesoderm, intermediate mesoderm and lateral plate mesoderm (Ivanovitch et al., 2021; Chan et al., 2013). Cardiopotent cells, also called cardiac progenitor cells, are derived from the lateral plate mesoderm during early gastrulation (Yamada and Takakuwa, 2012; Moretti et al., 2006; Garry and Olson, 2006). Cardiac progenitors are prepatterned within the primitive streak, with the atrial and ventricular cells arising at different anterior-posterior positions (Chan et al., 2013). Foxa2+ cardiac progenitors give rise primarily to the cardiovascular cells of the ventricles and are the first cardiogenic cells that migrate to the anterior side of the embryo (Bardot et al., 2017). These cells comprise approximately half of the cardiomyocyte population (Bardot et al., 2017). The right ventricle and outflow tract progenitors are found in anterior/distal primitive streak, where cells are exposed to a higher ratio of activin A to bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) signaling, whereas atrial progenitors are specified in the proximal primitive streak, where the activin A to BMP4 ratio is low (Ivanovitch et al., 2021).

Brachyury (T) gene expression is also required for the formation of posterior mesoderm in mice and zebrafish (Schulte-Merker and Smith, 1995; Herrmann et al., 1990). Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and Activin A can promote the expression of the T homolog, Xbra, in the Xenopus presumptive ectoderm (Smith et al., 1991). T-box transcription factors and T are intrinsic factors that are crucial for the initiation of mesoderm differentiation and patterning of the primitive streak and are regulated by the Wnt signaling pathway from the adjacent embryonic midline and posterior regions of the embryo, indicating the importance of Wnt signaling at this stage of development (Yamaguchi et al., 1999).

Cardiac specification

Several transcription factors for cardiac development have been identified (Olson, 2006). These include MESP1, which specifies the cardiac mesodermal population and is expressed in the primitive streak around CS6-7 or E6.5. In MESP1-null embryos, severe cardiac abnormalities are observed, leading to cardiac lethality by E10.5 (Saga et al., 1999). Furthermore, in a double knockout of MESP1 and its homolog MESP2, mesoderm progenitors do not contribute to heart development, indicating that MESP1/2 expression is essential for cardiac mesoderm formation (Kitajima et al., 2000).

By CS8 or E7.5, specific regions of the mesoderm differentiate to form cardiovascular progenitor cells, which can be divided into cells that form the first heart field (FHF) and cells that form the second heart field (SHF) (Paige et al., 2015). When Wnt inhibitors such as dickkopf 1 (DKK1) or crescent are administered to posterior lateral plate mesoderm, heart muscle development is induced and erythropoiesis is suppressed (Marvin et al., 2001, Naito et al., 2006). Meanwhile, ectopic expression of WNT8 or WNT3a in precardiac mesoderm inhibits heart muscle formation and promotes erythropoiesis (Marvin et al., 2001). In mouse embryonic stem cells, Wnt/β-catenin signaling acts biphasically; early treatment with Wnt3a stimulates mesoderm induction and cardiac differentiation, whereas late activation of β-catenin signaling impairs cardiac differentiation (Ueno et al., 2007). In combination with BMP and FGF, Wnt inhibition results in the activation of key upstream cardiac transcriptional regulatory genes NKX2-5, GATA4 and TBX5, which are required for the initiation of cardiac-like gene expression (Kelly et al., 2014).

The formation of the linear heart tube is mostly initiated by the contribution of the FHF, which eventually gives rise to the inflow tract and the majority of the left ventricle (Brade et al., 2013). FHF progenitors at this stage specifically express TBX5 and HCN4 (Später et al., 2013; Bruneau et al., 1999). The SHF develops slightly later and is less differentiated, providing cardiac progenitors that proliferate to promote the expansion of the heart tube (Kelly, 2012). The right ventricle and outflow tract are exclusively generated by the SHF (Buckingham et al., 2005). These SHF cardiomyocytes are marked with TBX1, ISL1 and HAND2 (Moretti et al., 2006; Stanley et al., 2002).

Together, these studies demonstrate that Wnt signals in different parts of the mesoderm are repressed as required for cardiac specification of these regions. Most in vitro protocols for directed cardiac differentiation of pluripotent stem cells incorporate this inhibition of Wnt signaling through the application of porcupine small-molecule inhibitors including IWP-2, IWR1 and Wnt-C59 (Lian et al., 2012; Burridge et al., 2014).

Developmental heart growth

Organ size regulation is an important aspect of cardiac development. The heart must grow large enough to generate sufficient cardiac output, and regional under- or overgrowth may result in septal wall defects, hypoplastic ventricle(s) or obstruction of the outflow tract(s) (Heallen et al., 2011). Heart growth during development is regulated by a combination of cardiomyocyte differentiation, proliferation and hypertrophy.

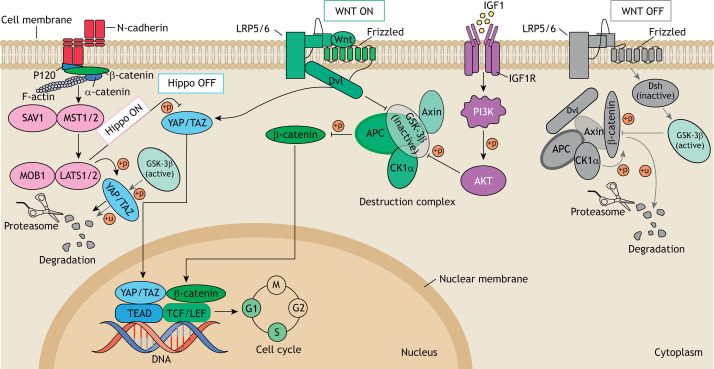

The human heart undergoes a dramatic proliferation period from CS9-CS16, resulting in a 600-fold increase in heart volume in just 3 weeks (de Bakker et al., 2016). First, the cardiac crescent fuses at the midline and gives rise to the FHF-derived linear heart tube, which subsequently commences beating and undergoes looping. Hereafter, the linear heart tube expands by drastic proliferation and recruitment of SHF cardiac progenitor cells that migrate from the pericardial cavity to the dorsal and caudal heart tube regions while undergoing differentiation (Kelly et al., 2014). Their rapid proliferation is regulated by canonical Wnt signaling (Günthel et al., 2018; Kwon et al., 2007). Upon the presence of the receptor-bound ligands WNT5A and WNT11, active β-catenin enters the nucleus, where it acts as a transcriptional co-activator of the T-cell factor (TCF) and leukemia enhancer factor (LEF) transcription factors to activate Wnt target genes involved in cell proliferation such as axin 2 (AXIN2), cyclin D1 (CCND1) and lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF1) (Cadigan and Waterman, 2012; Stamos and Weis, 2013) (Fig. 1). Conversely, in the absence of Wnt ligands, a complex containing adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), casein kinase 1 (Ck1) and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) mediates phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and, ultimately, degradation of β-catenin (Cadigan and Waterman, 2012; Stamos and Weis, 2013) (Fig. 1). Conditional knockout studies for β-catenin in the SHF produce outflow tract abnormalities and impaired right ventricular development (Qyang et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

There is interplay between Wnt, Hippo and insulin signaling during cardiomyocyte proliferation. Activation of the Hippo, canonical Wnt or IGF1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathways causes YAP/TAZ and β-catenin to enter the nucleus and cluster with their DNA-binding partners TEAD and TCF/LEF, which activates transcription of target genes and induces cell cycle activation. Conversely, when Dsh is inactivated due to lack of Wnt proteins, activated GSK-3β can phosphorylate β-catenin or YAP/TAZ, ultimately resulting in their degradation by the proteasome. Hippo signaling induced by, for example, N-cadherin junction-mediated cell-cell contact leads to the degradation of the YAP/TAZ complex through the MST1/2-SAV1-LATS1/2-MOB1-YAP/TAZ cascade. IGF1/PI3K/AKT signaling can facilitate the entry of β-catenin into the nucleus via AKT kinase, which phosphorylates GSK-3β to inhibit its activation. AKT, RACα serine/threonine-protein kinase; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli protein; CK1α, casein kinase 1α; Dsh, disheveled; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3; IGF1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R, IGF1 receptor; LATS1/2, large tumor suppressor homologue 1/2; LRP5/6, low-density-lipoprotein-related protein 5/6; MOB1, MOB kinase activator 1; MST1/2, mammalian STE20-like protein kinase 1/2; PI3 K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SAV1, protein Salvador homologue 1; TAZ, transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif; TCF/LEF, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor; TEAD, TEA domain transcription factor family members; YAP, yes-associated protein; +p, phosphorylation; +u, ubiquitination.

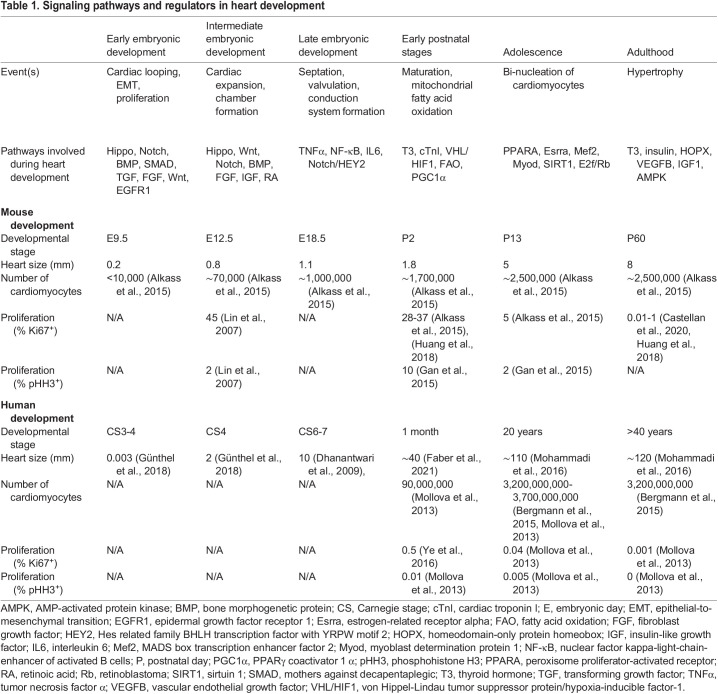

After specification and terminal differentiation of cardiac progenitors into cardiomyocytes, the developing heart predominantly increases its size and mass via the proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes (Günthel et al., 2018) (Table 1). In mice, between E8.0 and E11.0, cardiomyocyte numbers increase 100-fold from ∼700 to ∼70,000 (De Boer et al., 2012) (Fig. 2A,C). During this massive growth phase, the size of the individual cardiomyocytes remains relatively constant. After E11.0, proliferation continues but at a slower rate, with cardiomyocyte numbers approaching 1,000,000 by E18.5 (de Boer et al., 2012). The ballooning ventricles exhibit the highest proliferation rates during this period (Moorman and Christoffels, 2003; Moorman et al., 2010). By contrast, the atrioventricular canal, outflow tract and inner curvature regions have lower proliferation rates and thereby preserve the slow contraction characteristics of the heart tube (De Jong et al., 1992).

Table 1.

Signaling pathways and regulators in heart development

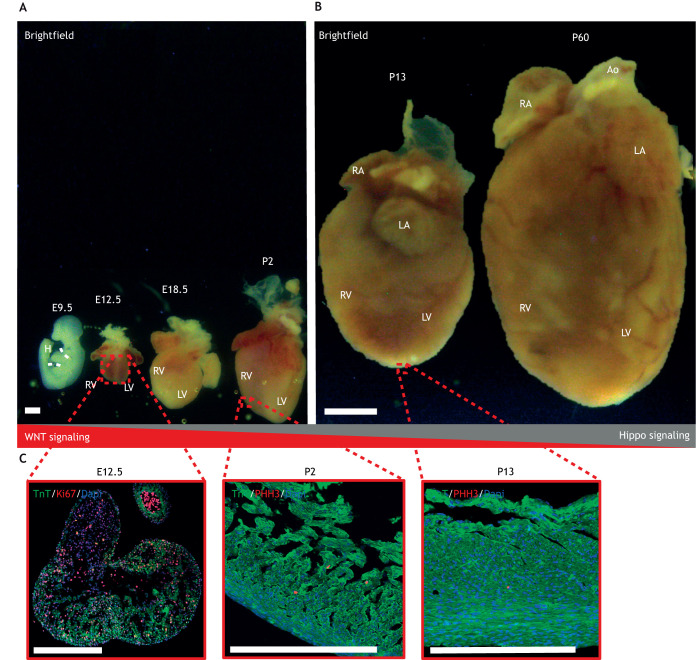

Fig. 2.

Heart size at selected stages of normal cardiac development. (A) Brightfield images capturing murine hyperplasia over embryonic day (E)9.5 (whole embryo; dashed white lines indicate the location of the heart), E12.5, E18.5 and postnatal day (P)2. (B) Brightfield images capturing murine hypertrophy from P13 to P60. (C) Immunofluorescent images showing pHH3+ cells in E12.5 and Ki67+ in LV cells of P2 and P13 hearts. pHH3 and Ki67 are proliferation markers and TnT is a cardiomyocyte marker. Ao, aorta; H, heart; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; TnT, troponin T; pHH3, phosphohistone H3. Figure is adapted from Buikema et al. (2013, 2020) and is available to view on Figshare alongside detailed Materials and Methods: 10.6084/m9.figshare.23607306. Scale bars: ∼1 mm (A,C); 5 mm (B).

Proliferation rates may also vary within the same region depending on the developmental stage. Within the ventricles, proliferation rates are low during the formation of the trabecular network (Sedmera and Thompson, 2011). The trabeculae contribute to cardiac contractility, channel expression and energy metabolism, and start to develop at the luminal side of the myocardium by E9.5 or CS12 (Meyer et al., 2020; Günthel et al., 2018). Later in development, from CS12 until CS16, proliferation rates increase and the compacted ventricular chamber myocardium shows high expression of proliferative markers such as Ki67 and pHH3 (Buikema et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2015). These changes to ventricular proliferation rates are due to Wnt signaling. Canonical Wnt signaling is downregulated in the trabecular myocardium, which is consistent with the lower proliferation rates observed here (Buikema et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2015). By contrast, conditional knockout studies in mice have shown that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Notch signaling are essential for trabecular development (Gassmann et al., 1995; Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). When proliferation rates in the ventricle increase, Wnt/β-catenin is essential for the exponential growth of the compacted ventricular myocardium; the increase in cardiomyocyte proliferation rates as you move from the inner trabeculae to outer compact myocardium corresponds with the graded activity of canonical Wnt signaling (Buikema et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2015). Consistent with this, β-catenin is mainly active in the compact myocardium, where it is expressed by the majority of proliferating cardiomyocytes (Buikema et al., 2013).

After CS16 and E12.5, cardiomyocyte proliferation rates decline further to maintain normal heart and embryo size ratios until birth. Postnatal heart growth is regulated via cellular hypertrophy (Günthel, Barnett, and Christoffels, 2018) (Fig. 2B,C). The insulin-like growth factor (IGF)/Akt pathway appears to promote physiological (and pathogenic) hypertrophy by activation of the ERK/MAPK and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathways in postnatal cardiomyocytes (DeBosch et al., 2006; Liu et al., 1996; Li et al., 2011).

Interplay between Wnt, Hippo and IGF signaling during cardiomyocyte expansion

The major regulator of cardiac size is the Hippo pathway. This pathway regulates growth and progenitor genes such as SOX2, SNAI2, CCND1, CDC20 and MYCL in cardiomyocytes via the MST1/2-SAV1-LATS1/2-MOB1-YAP/TAZ cascade (Heallen et al., 2011) (Fig. 1). YAP, a central protein within the Hippo signaling pathway, is activated at CS10 (Singh et al., 2016). Genetic inhibition of Hippo signaling in the embryonic heart leads to a lack of organ size control and lethal cardiomegaly shortly after birth (von Gise et al., 2012). For example, mouse models harboring various embryonic deletions of the Hippo pathway members SAV1, MST1/2 and LATS2 display overgrown hearts and thickened ventricles owing to an excess of cardiomyocytes (Del Re, 2014). Downstream analysis in Hippo mutant hearts revealed that a lack of downregulation of canonical Wnt target genes and cell cycle regulators could explain the observed hyperplasia and cardiomegaly (Heallen et al., 2011). By contrast, upregulation of Hippo signaling leads to a downregulation of YAP and Wnt/β-catenin signaling to restrain heart size (Kim et al., 2017). Cardiac-specific deletion of YAP also impedes neonatal heart regeneration, resulting in a fibrotic response that generates scar tissue (Xin et al., 2013).

Cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ can also increase cytosolic retention of β-catenin, and thereby negatively regulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Imajo et al., 2012). Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) indicated that YAP/TAZ and β-catenin form a common regulatory complex at the SOX2 and SNAI2 gene loci (Heallen et al., 2011). Activating YAP also leads to upregulation of the IGF/Akt pathway, resulting in the inhibition of GSK-3β, stabilization of β-catenin and transcription of Wnt target genes to enhance cardiomyocyte proliferation (Xin et al., 2011) (Fig. 1). During development, IGF signaling directs cardiomyocyte proliferation between E9.5 and E12.5, and IGF knockout mice exhibit decreased ventricular proliferation (Li et al., 2011). Interestingly, knockout of IGF is non-lethal and by E14.5 the ventricular wall size is comparable with that of wild-type mice (Li et al., 2011; Díaz Del Moral et al., 2021).

The Wnt/β-catenin, IGF/Akt and Hippo/YAP pathways form a complex signaling network that regulates the balance between proliferation, differentiation and maturation of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1). It has generally been concluded that high Wnt, high IGF and low Hippo signaling results in proliferative growth of embryonic cardiomyocytes, whereas high Hippo signaling overrules Wnt and IGF to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and prevent cardiomegaly.

Cardiomyocyte cell biology in vitro

Developmental shortcuts for human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte differentiation

Cardiomyocytes derived from pluripotent stem cells represent a promising source of cells for disease modeling, drug screens and/or cardiac regenerative medicine (Madonna et al., 2019). The untangling of cues that drive cardiac development has identified growth factors, transcriptional regulators and signaling cascades that can promote the differentiation of cardiac cells from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). Initial protocols for embryonic stem cell differentiation required formation of embryoid bodies to generate various cell types (Rungarunlert et al., 2009), and downstream applications for cardiac cell biology were limited due to extremely low percentages of cardiomyocyte yield (Osafune et al., 2008). Previously, co-culture of hESCs with visceral endoderm-like cells induced cardiomyocyte differentiation, producing beating areas in ∼35% of the culture surface (Mummery et al., 2003). Due to the addition of insulin and serum, however, only 2-3% of the cells were cardiomyocytes. The number of beating colonies increased 10-fold with the administration of serum- and insulin-free media, whereafter each beating colony contained ∼25% cardiomyocytes. Moreover, in situ hybridization demonstrated that the streak ectoderm displays the highest level of mRNA for both Wnt3a and Wnt8c (Marvin et al., 2001). In retrospect, the expression of Wnt inhibitors in the ectoderm may be the underlying mechanism for the increased cardiomyocyte differentiation efficiency (Piccolo et al., 1999). Overall, it appears that the timing and relative expression of different growth factor combinations induce then pattern the cardiogenic mesoderm.

Subsequent studies identified important roles for the activin A, insulin, Wnt and BMP pathways in the establishment of cardiovascular cells (Klaus et al., 2007; Schneider and Mercola, 2001; Liu et al., 1999). Activin A and transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) stimulation promotes cardiac mesoderm formation in mouse embryonic stem cells (Moretti et al., 2006; Kattman et al., 2006) and addition of activin A and BMP4 induces endogenous Wnt signaling and mesoderm-like cells from human embryonic stem cell sources (Paige et al., 2010). Remarkably small changes in BMP4 and activin A concentrations can drive the specification of the FHF, the anterior SHF and the posterior SHF (Yang et al., 2022) from distinct stem cell-derived mesoderm populations (Kattman et al., 2011), ultimately affecting the relative numbers of atrial versus ventricular cardiomyocytes (Lee et al., 2017). Although cardiomyocytes produced in this way may be high quality, scaling up these protocols is challenging due to the stability and cost of growth factors involved, which must be precisely applied to achieve this delicate balance.

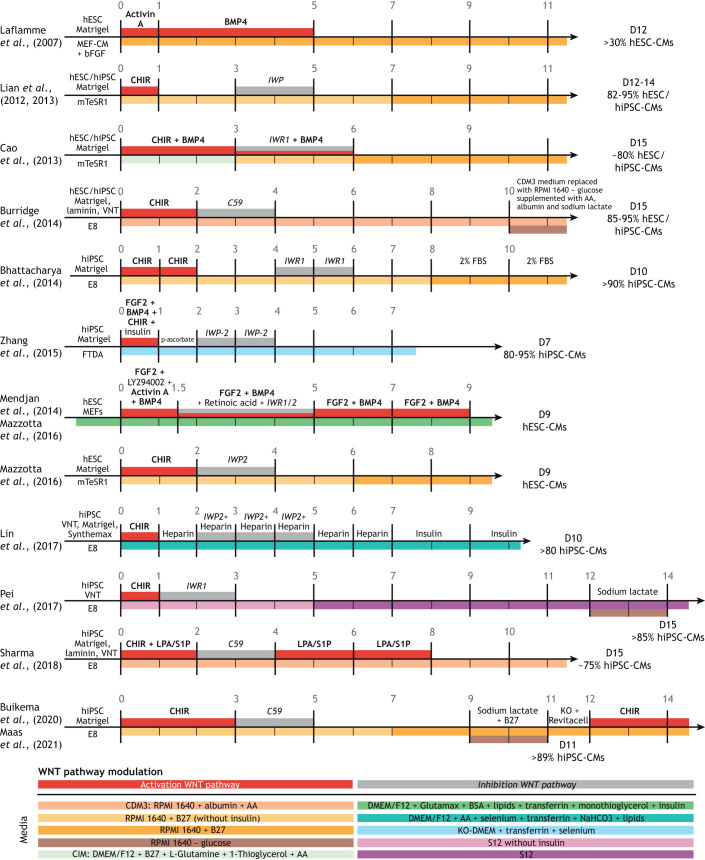

The ability to reprogram patient somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) represented a key turning point for the field (Takahashi et al., 2007). The potential to differentiate these patient-specific cells into many cell types, including functional cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) fueled a search for signaling molecules to replace the growth factors. In vitro, molecular inhibition of GSK-3β using small molecules such as CHIR99021 leads to nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and thus the transcription of Wnt target genes (Lian et al., 2012). Activation of Wnt signaling in monolayer-based hESC and hiPSC cultures results in efficient mesoderm-like cell formation, and subsequent inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway promotes the terminal differentiation of these mesoderm-like cells into cardiomyocytes (Paige et al., 2010; Lian et al., 2012). The current standard in monolayer-based directed differentiation protocols uses this two-step Wnt pathway modulation to generate >80% hiPSC-CMs within 7 days of culture (Paige et al., 2010; Lian et al., 2012) (Fig. 3). Altogether, the development of small molecule-based directed differentiation protocols has facilitated reliable and cost-effective production of both atrial and ventricular hiPSC-CMs. However, cell type heterogeneity presents a challenge, as homogeneous populations of subtype-specific cardiomyocytes are essential for drug discovery, cardiovascular disease modeling and cardiotoxicity screens (Zhang et al., 2009).

Fig. 3.

Summary of recent directed cardiac differentiation and expansion protocols for human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Schematics of pluripotent stem cell monolayer-based cardiomyocyte differentiation protocols. The days of each protocol are indicated by the vertical lines. Corresponding articles are shown on the left. Initial stem cell conditions, before the start of the differentiation, are shown to the left of day 0 on each timeline. Differentiation efficiency is indicated on the right side, where D indicates the day on which the differentiation efficiency was measured. The media used for differentiation are indicated by different colors below the time axis, with any additional components listed above the time axis. The red and grey boxes depicted above the time axis indicate activation or inhibition of the Wnt pathway, respectively. Key components responsible for modulating Wnt activity are indicated in bold for Wnt activation or italics for Wnt inhibition. Abbreviations: AA, L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate; bFGF/FGF2, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CHIR, CHIR99021; DMEM, Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum; hESCs, human embryonic stem cells; hiPSC, human induced pluripotent stem cells; IWP, inhibitor of Wnt production; KO-DMEM, knockout DMEM; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; RPMI, Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; VNT, vitronectin. E8, FDTA and mTeSR1 are stem cell media. C59 and IWR1 are inhibitors of the Wnt pathway. B27 is a commercially available cell culture supplement. Created with BioRender.com.

Developmental shortcuts for human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte expansion

Robust generation of large quantities of hiPSC-CMs from patient donors remains a significant hurdle. Conventional approaches to tackle this problem use large numbers of hiPSCs, which is very costly, and the differentiation efficiency is highly variable due to lack of control of important culture parameters (Laco et al., 2018). Moreover, the subsequent expansion of hiPSC-CM cultures is generally modest (<10-fold) (Table 2).

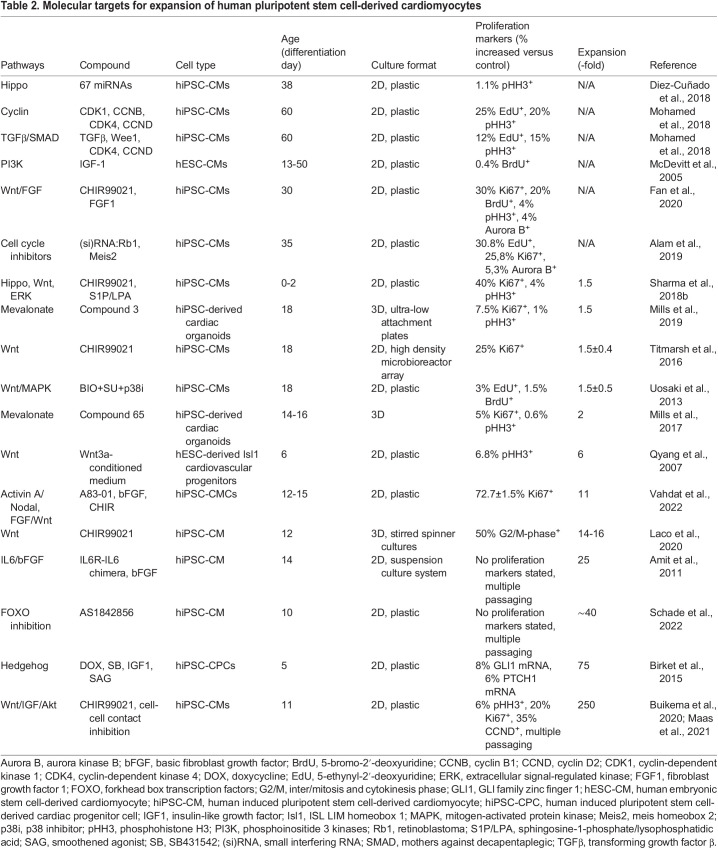

Table 2.

Molecular targets for expansion of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes

In vitro studies have identified multiple pathways controlling the proliferation of hiPSC-CMs. Computational approaches and chemical screens for cardiomyocyte proliferation regulators found 67 miRNAs targeting different components of the Hippo pathway (Diez-Cuñado et al., 2018) (Table 2). Hippo signaling appears to be upregulated in hiPSC-CMs cultured on plastic, but altering substrate stiffness has no effect on the fraction of proliferative cardiomyocytes, and none of the small molecule Hippo pathway inhibitors has been reported to enhance cardiomyocyte proliferation in vitro (Buikema et al., 2020).

The TGFβ pathway regulates the cell cycle in hiPSC-CMs, where it directly boosts the production of p27 in a Smad-dependent manner, allowing p27 to inhibit the activity of G1 cyclins (Toyoshima and Hunter, 1994; Kodo et al., 2016). The combined upregulation of CDK1, CCNB, CDK4 and CCND successfully upregulates cardiomyocyte proliferation markers in hiPSC-CMs (Mohamed et al., 2018), and inhibiting Wee1 and TGFβ promotes CDK1 phosphorylation, thus promoting G2/M phase entry (Mohamed et al., 2018) (Table 2).

Multiple hormones are implicated in the regulation of fetal growth, and many of these take on considerably different roles during early postnatal life. In utero, the human heart relies predominantly on high concentrations of carbohydrates, whereas the postnatal myocardium also uses fatty acid-rich substrates (Kolwicz et al., 2013). Insulin, prolactin, IGF1, IGF2 and thyroid-associated hormones are involved in anabolism during heart development (Díaz Del Moral et al., 2021). The growth factor IGF1 was shown to enhance the proliferation of hESC-derived cardiomyocytes via activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (McDevitt et al., 2005). Thyroid hormone or 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (T3) inhibits proliferation and drives the maturation of cardiomyocytes before birth (Chattergoon et al., 2019). In parallel to IGF1, insulin increases proliferation of hiPSC-CMs and cardiac organoids (Mills et al., 2017) (Table 2). However, insulin does not rescue cell cycle arrest, likely due to altered substrate use and fatty acid metabolism in the treated cardiomyocytes, so this effect is short-lived (Mills et al., 2017).

During development and hiPSC differentiation, the GSK-3β/Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade exerts multiphasic effects on cardiac differentiation and proliferation. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is essential for cardiac repair and has been implicated in cardiac diseases (Titmarsh et al., 2016). Multiple studies in 2D and 3D in vitro cell models have described a significant proliferative effect of small molecules that inhibit GSK-3β and activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling, such as CHIR99021 (Buikema et al., 2013; Titmarsh et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2018b; Uosaki et al., 2013) (Table 2).

Attempts have also been made to increase cardiomyocyte yield by first expanding the production of hiPSCs and then inducing cardiac differentiation (Le and Hasegawa, 2019). Conventional methods for this approach include the culture of hiPSCs in a 2D monolayer at larger surface areas (using T175 flasks, CompacT SelecT, roller bottles or CellCube) (Tohyama et al., 2017; Soares et al., 2014). Although these 2D culture monolayers can increase hiPSC cell number efficiently, hiPSC medium is very costly, and the differentiation efficiency is highly variable due to lack of control of important culture parameters such as the confluency of the hiPSCs and the timing of compound addition (Tohyama et al., 2017). More recently, advanced 3D culture strategies such as microcarriers, 3D aggregation and bioreactors have attracted interest and have proven suitable for large-scale culturing of hiPSCs (Borys et al., 2020; Abecasis et al., 2017). This 3D culture approach improves the efficiency of hiPSC-CM production and reduces variability in differentiation outcomes (Hofer and Lutolf, 2021). However, the cost of the medium and the need for dissociation during harvesting represent hurdles for subsequent differentiation applications (Le and Hasegawa, 2019).

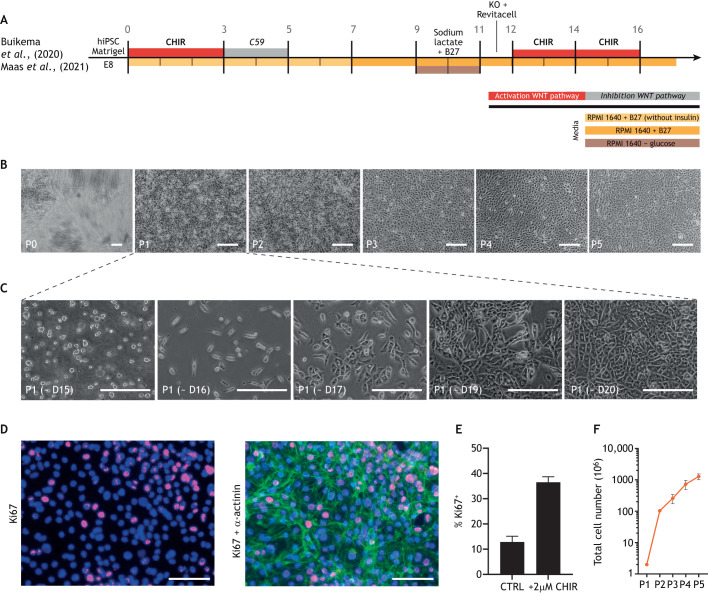

Recently, we discovered that cell-cell contact promotes terminal differentiation and maturation, rather than proliferation, in densely cultured hiPSC-CMs (Buikema et al., 2020). Concomitant activation of Wnt signaling by CHIR99021 and cell-cell contact inhibition by low cell density serial passaging resulted in a massive proliferative response in the hiPSC-CMs (Buikema et al., 2020; Maas et al., 2021) (Fig. 4). These hiPSC-CMs exhibited immature functional properties, such as reduced contractility and underdeveloped sarcomeres; however, upon withdrawal of CHIR99021, cells quickly exited the cell cycle and terminally differentiated (Buikema et al., 2020). It appears that insulin is required for long-term hiPSC-CM culture recapitulating cardiac development (Lian et al., 2013; Govindsamy et al., 2018), so we also chose to optimize our protocol for proliferation induction with B-27 medium containing insulin. In summary, Wnt activation together with removal of cell-cell contacts transiently increases the window for massive expansion of immature hiPSC-CMs.

Fig. 4.

Overview of Wnt modulation during hiPSC-CM differentiation and expansion. (A) Schematic overview of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte (hiPSC-CM) differentiation. Created with BioRender.com. (B) Brightfield images of hiPSC-CMs over multiple passages including expansion illustrating the process of cell-cell contact removal via sparse passaging (∼2.5×104 cells/cm2) with concomitant CHIR99021 administration in B27+insulin/RPMI media to facilitate massive expansion. (C) Brightfield images of hiPSC-CMs in expansion from days 15-20. (D) Immunofluorescence images of hiPSC-CMs stained for α-actinin (green), proliferation marker Ki67 (red) and nuclei (blue) as indicated. (E) Quantification of Ki67+ cells indicates that a 37% increase in hiPSC-CM proliferation can be promoted by administering 2 μM CHIR99021. (F) Quantification of hiPSC-CM number from P1 to P5 by sequentially expanding the hiPSC-CMs using CHIR99021 (CHIR). D, differentiation day; P, passage; RPMI, Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium. Figure is adapted from Maas et al. (2021) and is available to view on Figshare alongside detailed Materials and Methods: 10.6084/m9.figshare.23607282. Scale bars: 200 µM (B,C); 100 µM (D).

Massively expanded hiPSC-CMs are fully functional and could form a powerful source for tissue engineering applications and/or myocardial biopatches (Miyagawa et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2018). These protocols are still limited to producing a 100- to 250-fold increase in cell number (Buikema et al., 2020; Maas et al., 2021) (Table 2), but they are pushing the production process towards clinically relevant cardiomyocyte numbers. For example, one batch of massively expanded hiPSC-CMs can be used to generate large numbers of 3D engineered heart tissues (EHTs) or to conduct large 2D screens (Hansen et al., 2010; Calpe and Kovacs, 2020). Moreover, hiPSC-CM-derived tissues or cell injections can form large grafts after transplantation into injured animal hearts (Shiba et al., 2016). Upon injection, previous studies have shown electrical coupling of hiPSC-CMs to host myocardium, but also arrhythmic events (Hirt et al., 2012; Shiba et al., 2012). Recent work has shown that these arrhythmic events can be overcome via maturation-guided editing of hiPSC-CM ion channels, thereby improving electrophysiological function (Marchiano et al. 2023; Ottaviani et al., 2023). These approaches require 10-750 million cells for restoration of contractile function after ischemic injury in macaque monkeys (Anderson et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2018a). Unfortunately, despite the recent methods to improve cardiomyocyte maturity, the overall maturation status of hiPSC-CMs with or without expansion remains low. Therefore, hiPSC-CM grafts retain different electrical properties compared with the host tissue, which could lead to increased arrhythmia risk (Fassina et al., 2022).

Discussion

The further untangling of the cues that drive cardiomyocyte differentiation, proliferation and maturation will lead to increased understanding and improved drug screening options and treatments for cardiac diseases. This Review compares the pathways regulating heart growth in vivo with the molecular targets that promote in vitro cardiomyocyte production. The massive expansion of hiPSC-CMs that can be achieved via Wnt/β-catenin signaling modulation (Table 2, Figs 3 and 4) provides a framework for advanced basic and translational cell biology applications in cardiovascular medicine, and several preclinical trials are making use of these hiPSC-CMs (Sharma et al., 2018a; Hnatiuk et al., 2021).

The current knowledge from cardiac development has resulted in relatively easy methods for hiPSC-CM generation. Further understanding of exact cues for long-term proliferation and terminal differentiation, however, are required to produce unlimited numbers of mature cardiomyocytes. The recent discovery of partly-immortalized atrial cardiomyocytes represents a powerful approach for atrial disease modeling in vitro (Harlaar et al., 2022). However, their in vivo use may provoke safety concerns. Nevertheless, these approaches for expansion of cardiomyocytes illustrate that functional and beating cardiomyocytes can self-replicate before terminally differentiating upon growth stimuli withdrawal. Interestingly, direct activation of Wnt/β-catenin with CHIR99021 produces cardioprotective effects upon myocardial infarction in both small and large mammals (Fan et al., 2020). However, there is little evidence for induction of terminally differentiated cardiomyocyte proliferation after administration of CHIR99021 upon ischemic injury (Fan et al., 2020). This lack of proliferative capacity in terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes is somewhat in line with developmental studies illustrating that Hippo signaling controls cell-cycle arrest in adult cardiomyocytes (Xin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). Genetic modification of the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway results in dedifferentiation of adult myocardium with a subsequent regenerative response to ischemic injury (Leach et al., 2017; Monroe et al., 2019). Combined with novel DNA, RNA or nanoparticle local delivery technologies, signaling pathways hold promise as druggable targets in cardiovascular medicine (Braga et al., 2021). Future hiPSC-CM studies should focus on further simplification of the exact cues required for cardiomyocyte production, and should incorporate other myocyte subtypes required for regional repair of the heart, as well as more specific cardiac tissue generation.

Footnotes

Funding

R.G.C.M. is supported by a fellowship from the Stichting PLN. F.W.v.d.D. acknowledges support from the Dutch Cardiovascular Alliance. Q.Y. is supported by PhD fellowship from China Scholarship Council (201706170068). J.v.d.V. is supported by grants from Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek–ZonMw (91818602 VICI), ZonMw and Hartstichting for the translational research program, project 95105003; the Dutch Cardiovascular Alliance grant Double Dose 2021; the Fondation Leducq grant number 20CVD01; and Proper Therapy project funded by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, domain Applied and Engineering Sciences (NWO-AES), the Association of Collaborating Health Foundations (Health~Holland), and ZonMw within the human models 2.0 call. S.M.W. is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1RM1GM131981-03); American Heart Association Established Investigator Award; Additional Ventures Foundation; National Science Foundation RECODE Project; and the Joan and Sanford I. Weill Department of Medicine Endowed Scholarship Fund. J.P.G.S. is supported by H2020-EVICARE (725229) of the European Research Council and ZonMw PSIDER grant (10250022110004). J.W.B. is supported by a Dekker Senior Clinical Scientist personal grant from the Hartstichting; Netherlands Heart Institute Fellowship; and CVON-Dosis young talent grant from the Hartstichting (CVON-Dosis 2014–40). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Contributor Information

Joost P. G. Sluijter, Email: j.sluijter@umcutrecht.nl.

Jan W. Buikema, Email: j.w.buikema@amsterdamumc.nl.

References

- Abecasis, B., Aguiar, T., Arnault, É., Costa, R., Gomes-Alves, P., Aspegren, A., Serra, M. and Alves, P. M. (2017). Expansion of 3D human induced pluripotent stem cell aggregates in bioreactors: bioprocess intensification and scaling-up approaches. J. Biotechnol. 246, 81-93. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhyapak, S. M. (2022). The impact of left ventricular geometry and remodeling on prognosis of heart failure in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J. Card. Surg. 37, 2168-2171. 10.1111/jocs.16438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam, P., Haile, B., Arif, M., Pandey, R., Rokvic, M., Nieman, M., Maliken, B. D., Paul, A., Wang, Y. G., Sadayappan, S.et al. (2019). Inhibition of senescence-associated genes Rb1 and Meis2 in adult cardiomyocytes results in cell cycle reentry and cardiac repair post-myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012089. 10.1161/JAHA.119.012089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkass, K., Panula, J., Westman, M., Wu, T. D., Guerquin-Kern, J. L. and Bergmann, O. (2015). No evidence for cardiomyocyte number expansion in preadolescent mice. Cell 163, 1026-1036. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit, M., Laevsky, I., Miropolsky, Y., Shariki, K., Peri, M. and Itskovitz-Eldor, J. (2011). Dynamic suspension culture for scalable expansion of undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 6, 572-579. 10.1038/nprot.2011.325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. E., Goldhaber, J., Houser, S. R., Puceat, M. and Sussman, M. A. (2014). Embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes are not ready for human trials. Circ. Res. 115, 335-338. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardot, E., Calderon, D., Santoriello, F., Han, S., Cheung, K., Jadhav, B., Burtscher, I., Artap, S., Jain, R., Epstein, J.et al. (2017). foxa2 identifies a cardiac progenitor population with ventricular differentiation potential. Nat. Commun. 8, 14428. 10.1038/ncomms14428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, O., Bhardwaj, R. D., Bernard, S., Zdunek, S., Barnabeì-Heider, F., Walsh, S., Zupicich, J., Alkass, K., Buchholz, B. A., Druid, H.et al. (2009). Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324, 98-102. 10.1126/science.1164680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, O., Zdunek, S., Felker, A., Salehpour, M., Alkass, K., Bernard, S., Sjostrom, S. L., Szewczykowska, M., Jackowska, T., Dos Remedios, C.et al. (2015). Dynamics of cell generation and turnover in the human heart. Cell 161, 1566-1575. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birket, M., Ribeiro, M., Verkerk, A., Ward, D., Leitoguinho, A. R., den Hartogh, S. C., Orlova, V. V., Devalla, H. D., Schwach, V., Bellin, M., et al. (2015). Expansion and patterning of cardiovascular progenitors derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 970-979. 10.1038/nbt.3271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borys, B. S., So, T., Colter, J., Dang, T., Roberts, E. L., Revay, T., Larijani, L., Krawetz, R., Lewis, I., Argiropoulos, B.et al. (2020). Optimized serial expansion of human induced pluripotent stem cells using low–density inoculation to generate clinically relevant quantities in vertical–wheel bioreactors. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 9, 1036. 10.1002/sctm.19-0406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brade, T., Pane, L. S., Moretti, A., Chien, K. R. and Laugwitz, K.-L. (2013). Embryonic heart progenitors and cardiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, a013847. 10.1101/cshperspect.a013847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga, L., Ali, H., Secco, I. and Giacca, M. (2021). Non-coding RNA therapeutics for cardiac regeneration. Cardiovasc. Res. 117, 674-693. 10.1093/cvr/cvaa071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, M.-A., Sheehy, S. P. and Parker, K. K. (2008). Sarcomere alignment is regulated by myocyte shape. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 65, 641-651. 10.1002/cm.20290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, B. G., Logan, M., Davis, N., Levi, T., Tabin, C. J., Seidman, J. G. and Seidman, C. E. (1999). Chamber-specific cardiac expression of Tbx5 and heart defects in holt-oram syndrome. Dev. Biol. 211, 100-108. 10.1006/dbio.1999.9298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, M., Meilhac, S. and Zaffran, S., (2005). Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 826-835. 10.1038/nrg1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buikema, J. W., Mady, A. S., Mittal, N. V., Atmanli, A., Caron, L., Doevendans, P. A., Sluijter, J. P. G. and Domian, I. J. (2013). Wnt/β-catenin signaling directs the regional expansion of first and second heart field-derived ventricular cardiomyocytes. Development 140, 4165-4176. 10.1242/dev.099325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buikema, J. W., Lee, S., Goodyer, W. R., Maas, R. G., Chirikian, O., Li, G., Miao, Y., Paige, S. L., Lee, D., Wu, H.et al. (2020). Wnt activation and reduced cell-cell contact synergistically induce massive expansion of functional human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Cell Stem Cell 27, 50-63.e5. 10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge, P. W., Keller, G., Gold, J. and Wu, J. C. (2012). Production of de Novo cardiomyocytes: human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 10, 16-28. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge, P. W., Matsa, E., Shukla, P., Lin, Z. C., Churko, J. M., Ebert, A. D., Lan, F., Diecke, S., Huber, B., Mordwinkin, N. M.et al. (2014). Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 11, 855-860. 10.1038/nmeth.2999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan, K. M. and Waterman, M. L. (2012). TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 4, a007906. 10.1101/cshperspect.a007906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calpe, B. and Kovacs, W. J. (2020). High-throughput screening in multicellular spheroids for target discovery in the tumor microenvironment. Exp. Opin. Drug Discov. 15, 955-967. 10.1080/17460441.2020.1756769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellan, R. F. P., Thomson, A., Moran, C. M. and Gray, G. A. (2020). Electrocardiogram-gated Kilohertz Visualisation (EKV) Ultrasound allows assessment of neonatal cardiac structural and functional maturation and longitudinal evaluation of regeneration after injury. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46, 167-179. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. S., Shi, X., Toyama, A., Arpke, R. ÂW., Dandapat, A., Iacovino, M., Kang, J., Le, G., Hagen, H. ÂR., Garry, D. ÂJ.et al. (2013). Mesp1 patterns mesoderm into cardiac, hematopoietic, or skeletal myogenic progenitors in a context-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell 12, 587-601. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattergoon, N. N., Louey, S., Scanlan, T., Lindgren, I., Giraud, G. D. and Thornburg, K. L. (2019). Thyroid hormone receptor function in maturing ovine cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. 597, 2163-2176. 10.1113/JP276874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci, W. S. (1997). Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 80, 15L-25L. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00845-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J. A., Shah, K. B., Quader, M. A., Cooke, R. H., Kasirajan, V., Rao, K. K., Smallfield, M. C., Tchoukina, I. and Tang, D. G. (2015). The total artificial heart. J. Thorac. Dis. 7, 2172-2180. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bakker, B. S., De Jong, K. H., Hagoort, J., De Bree, K., Besselink, C. T., De Kanter, F. E. C., Veldhuis, T., Bais, B., Schildmeijer, R., Ruijter, J. M.et al. (2016). An interactive three-dimensional digital atlas and quantitative database of human development. Science 354, aag0053. 10.1126/science.aag0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, R. A., Pinto, Y. and Van Veldhuisen, D. (2003). The imbalance between oxygen demand and supply as a potential mechanism in the pathophysiology of heart failure: the role of microvascular growth and abnormalities. Microcirculation 10, 113-126. 10.1080/713773607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, B. A., Van Den Berg, G., De Boer, P. A. J., Moorman, A. F. M. and Ruijter, J. M. (2012). Growth of the developing mouse heart: an interactive qualitative and quantitative 3D atlas. Dev. Biol. 368, 203-213. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, F., Opthof, T., Wilde, A. A., Janse, M. J., Charles, R., Lamers, W. H. and Moorman, A. F. (1992). Persisting zones of slow impulse conduction in developing chicken hearts. Circ. Res. 71, 240-250. 10.1161/01.res.71.2.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debosch, B., Treskov, I., Lupu, T. S., Weinheimer, C., Kovacs, A., Courtois, M. and Muslin, A. J. (2006). Akt1 is required for physiological cardiac growth. Circulation 113, 2097-2104. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re, D. P. (2014). The hippo signaling pathway: implications for heart regeneration and disease. Clin. Transl. Med. 3, 27. 10.1186/s40169-014-0027-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanantwari, P., Lee, E., Krishnan, A., Samtani, R., Yamada, S., Anderson, S., Lockett, E., Donofrio, M., Shiota, K., Leatherbury, L.et al. (2009). Human cardiac development in the first trimester: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and episcopic fluorescence image capture atlas. Circulation 120, 343-351. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.796698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Del Moral, S., Benaouicha, M., Muñoz-Chápuli, R. and Carmona, R. (2021). The insulin-like growth factor signalling pathway in cardiac development and regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 234. 10.3390/ijms23010234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Cuñado, M., Wei, K., Bushway, P. J., Maurya, M. R., Perera, R., Subramaniam, S., Ruiz-Lozano, P. and Mercola, M. (2018). miRNAs that induce human cardiomyocyte proliferation converge on the hippo pathway. Cell Rep. 23, 2168-2174. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenckhahn, J., Schwarz, Q. P., Gray, S., Laskowski, A., Kiriazis, H., Ming, Z., Harvey, R. P., Du, X.-J., Thorburn, D. R. and Cox, T. C. (2008). Compensatory growth of healthy cardiac cells in the presence of diseased cells restores tissue homeostasis during heart development. Dev. Cell 15, 521-533. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber, J. W., Hagoort, J., Moorman, A. F. M., Christoffels, V. M. and Jensen, B. (2021). Quantified growth of the human embryonic heart. Biol. Open 10, bio057059. 10.1242/bio.057059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C., Oduk, Y., Zhao, M., Lou, X., Tang, Y., Pretorius, D., Valarmathi, M. T., Walcott, G. P., Yang, J., Menasche, P.et al. (2020). Myocardial protection by nanomaterials formulated with CHIR99021 and FGF1. JCI Insight 5, e132796. 10.1172/jci.insight.132796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassina, D., Costa, C. M., Longobardi, S., Karabelas, E., Plank, G., Harding, S. E. and Niederer, S. A. (2022). Modelling the interaction between stem cells derived cardiomyocytes patches and host myocardium to aid non-arrhythmic engineered heart tissue design. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010030. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K. F., Cowie, M. R., Wood, D. A., Coats, A. J., Gibbs, J. S., Underwood, S. R., Turner, R. M., Poole-Wilson, P. A., Davies, S. W. and Sutton, G. C. (2001). Coronary artery disease as the cause of incident heart failure in the population. Eur. Heart J. 22, 228-236. 10.1053/euhj.2000.2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L., Gregorich, Z. R., Zhu, W., Mattapally, S., Oduk, Y., Lou, X., Kannappan, R., Borovjagin, A. V., Walcott, G. P., Pollard, A. E.et al. (2018). Large cardiac muscle patches engineered from human induced-pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac cells improve recovery from myocardial infarction in swine. Circulation 137, 1712-1730. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan, J., Sonntag, H.-J., Tang, M. K., Cai, D. and Lee, K. K. H. (2015). Integrative analysis of the developing postnatal mouse heart transcriptome. PLoS One 10, e0133288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry, D. J. and Olson, E. N. (2006). A common progenitor at the heart of development. Cell 127, 1101-1104. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, M., Casagranda, F., Orioli, D., Simon, H., Lai, C., Klein, R. and Lemke, G. (1995). Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature 378, 390-394. 10.1038/378390a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, B. L., Rochitte, C. E., Melin, J. A., Mcveigh, E. R., Bluemke, D. A., Wu, K. C., Becker, L. C. and Lima, J. A. (2000). Microvascular obstruction and left ventricular remodeling early after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 101, 2734-2741. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.2734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindsamy, A., Naidoo, S. and Cerf, M. E. (2018). Cardiac development and transcription factors: insulin signalling, insulin resistance, and intrauterine nutritional programming of cardiovascular disease. J. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 8547976. 10.1155/2018/8547976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grego-Bessa, J., Luna-Zurita, L., Del Monte, G., Bolós, V., Melgar, P., Arandilla, A., Garratt, A. N., Zang, H., Mukouyama, Y.-, Chen, H.et al. (2007). Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development. Dev. Cell 12, 415-429. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günthel, M., Barnett, P. and Christoffels, V. M. (2018). Development, proliferation, and growth of the mammalian heart. Mol. Ther. 26, 1599-1609. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A., Eder, A., Boì^nstrup, M., Flato, M., Mewe, M., Schaaf, S., Aksehirlioglu, B. Ì^, Schwoì^rer, A., Uebeler, J. and Eschenhagen, T. (2010). Development of a drug screening platform based on engineered heart tissue. Circ. Res. 107, 35-44. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlaar, N., Dekker, S. O., Zhang, J., Snabel, R. R., Veldkamp, M. W., Verkerk, A. O., Fabres, C. C., Schwach, V., Lerink, L. J. S., Rivaud, M. R.et al. (2022). Conditional immortalization of human atrial myocytes for the generation of in vitro models of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 389-402. 10.1038/s41551-021-00827-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubner, B. J., Schneider, J., Schweigmann, U., Schuetz, T., Dichtl, W., Velik-Salchner, C., Stein, J.-I. and Penninger, J. M. (2016). Functional recovery of a human neonatal heart after severe myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 118, 216-221. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heallen, T., Zhang, M., Wang, J., Bonilla-Claudio, M., Klysik, E., Johnson, R. L. and Martin, J. F. (2011). Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science 332, 458-461. 10.1126/science.1199010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, B. G., Labeit, S., Poustka, A., King, T. R. and Lehrach, H. (1990). Cloning of the T gene required in mesoderm formation in the mouse. Nature 343, 617-622. 10.1038/343617a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt, M. N., Sörensen, N. A., Bartholdt, L. M., Boeddinghaus, J., Schaaf, S., Eder, A., Vollert, I., Stã¶Hr, A., Schulze, T., Witten, A.et al. (2012). Increased afterload induces pathological cardiac hypertrophy: a new in vitro model. Basic Res. Cardiol. 107, 307. 10.1007/s00395-012-0307-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnatiuk, A. P., Briganti, F., Staudt, D. W. and Mercola, M. (2021). Human iPSC modeling of heart disease for drug development. Cell Chem. Biol. 28, 271-282. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, M. and Lutolf, M. P. (2021). Engineering organoids. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 402-420. 10.1038/s41578-021-00279-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W., Feng, Y., Liang, J., Yu, H., Wang, C., Wang, B., Wang, M., Jiang, L., Meng, W., Cai, W., et al. (2018). Loss of microRNA-128 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration. Nat. Commun. 9, 700. 10.1038/s41467-018-03019-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imajo, M., Miyatake, K., Iimura, A., Miyamoto, A. and Nishida, E. (2012). A molecular mechanism that links Hippo signalling to the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signalling. EMBO J. 31, 1109-1122. 10.1038/emboj.2011.487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovitch, K., Soro-Barrio, P., Chakravarty, P., Jones, R. A., Bell, D. M., Mousavy Gharavy, S. N., Stamataki, D., Delile, J., Smith, J. C. and Briscoe, J. (2021). Ventricular, atrial, and outflow tract heart progenitors arise from spatially and molecularly distinct regions of the primitive streak. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001200. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattman, S. J., Huber, T. L. and Keller, G. M. (2006). Multipotent Flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev. Cell 11, 723-732. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattman, S. J., Witty, A. D., Gagliardi, M., Dubois, N. C., Niapour, M., Hotta, A., Ellis, J. and Keller, G. (2011). Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell 8, 228-240. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R. G. (2012). The second heart field. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 100, 33-65. 10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R. G., Buckingham, M. E. and Moorman, A. F. (2014). Heart fields and cardiac morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, a015750. 10.1101/cshperspect.a015750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W., Khan, S. K., Gvozdenovic-Jeremic, J., Kim, Y., Dahlman, J., Kim, H., Park, O., Ishitani, T., Jho, E.-, Gao, B.et al. (2017). Hippo signaling interactions with Wnt/β-catenin and notch signaling repress liver tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 137-152. 10.1172/JCI88486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, S., Takagi, A., Inoue, T. and Saga, Y. (2000). MesP1 and MesP2 are essential for the development of cardiac mesoderm. Development 127, 3215-3226. 10.1242/dev.127.15.3215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus, A., Saga, Y., Taketo, M. M., Tzahor, E. and Birchmeier, W. (2007). Distinct roles of Wnt/β-Catenin and Bmp signaling during early cardiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 18531-18536. 10.1073/pnas.0703113104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodo, K., Ong, S.-G., Jahanbani, F., Termglinchan, V., Hirono, K., Inanloorahatloo, K., Ebert, A. D., Shukla, P., Abilez, O. J., Churko, J. M.et al. (2016). iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes reveal abnormal TGF-β signalling in left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 1031-1042. 10.1038/ncb3411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolwicz, S. C., Jr., Purohit, S. and Tian, R. (2013). Cardiac metabolism and its interactions with contraction, growth, and survival of the cardiomyocte. Circ. Res. 113, 603-616. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, C., Arnold, J., Hsiao, E. C., Taketo, M. M., Conklin, B. R. and Srivastava, D. (2007). Canonical Wnt signaling is a positive regulator of mammalian cardiac progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10894-10899. 10.1073/pnas.0704044104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laco, F., Woo, T. L., Zhong, Q., Szmyd, R., Ting, S., Khan, F. J., Chai, C. L. L., Reuveny, S., Chen, A. and Oh, S. (2018). Unraveling the inconsistencies of cardiac differentiation efficiency induced by the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 in human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 10, 1851-1866. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laco, F., Lam, A. T., Woo, T. L., Tong, G., Ho, V., Soong, P. L., Grishina, E., Lin, K. H., Reuveny, S. and Oh, S. K. (2020). Selection of human induced pluripotent stem cells lines optimization of cardiomyocytes differentiation in an integrated suspension microcarrier bioreactor. Stem Cell Res Ther. 11, 118. 10.1186/s13287-020-01618-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme, M. A. and Murry, C. E. (2011). Heart regeneration. Nature 473, 326-335. 10.1038/nature10147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach, J. P., Heallen, T., Zhang, M., Rahmani, M., Morikawa, Y., Hill, M. C., Segura, A., Willerson, J. T. and Martin, J. F. (2017). Hippo pathway deficiency reverses systolic heart failure after infarction. Nature 550, 260-264. 10.1038/nature24045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, M. N. T. and Hasegawa, K. (2019). Expansion culture of human pluripotent stem cells and production of cardiomyocytes. Bioengineering 6, 48. 10.3390/bioengineering6020048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. H., Protze, S. I., Laksman, Z., Backx, P. H. and Keller, G. M. (2017). Human pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes develop from distinct mesoderm populations. Cell Stem Cell 21, 179-94.e4. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, P., Cavallero, S., Gu, Y., Chen, T. H. P., Hughes, J., Hassan, A. B., Brüning, J. C., Pashmforoush, M. and Sucov, H. M. (2011). IGF signaling directs ventricular cardiomyocyte proliferation during embryonic heart development. Development 138, 1795-1805. 10.1242/dev.054338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian, X., Hsiao, C., Wilson, G., Zhu, K., Hazeltine, L. B., Azarin, S. M., Raval, K. K., Zhang, J., Kamp, T. J. and Palecek, S. P. (2012). Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1848-E1857. 10.1073/pnas.1200250109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian, X., Zhang, J., Zhu, K., Kamp, T. J. and Palecek, S. P. (2013). Insulin inhibits cardiac mesoderm, not mesendoderm, formation during cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells and modulation of canonical Wnt signaling can rescue this inhibition. Stem Cells 31, 447-457. 10.1002/stem.1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L., Cui, L., Zhou, W., Dufort, D., Zhang, X., Cai, C.-L., Bu, L., Yang, L., Martin, J., Kemler, R.et al. (2007). β-catenin directly regulates Islet1 expression in cardiovascular progenitors and is required for multiple aspects of cardiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9313-9318. 10.1073/pnas.0700923104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z., Zhou, P., Von Gise, A., Gu, F., Ma, Q., Chen, J., Guo, H., Van Gorp, P. R. R., Wang, D.-Z. and Pu, W. T. (2015). Pi3kcb links Hippo-YAP and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival. Circ. Res. 116, 35-45. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q., Yan, H., Dawes, N. J., Mottino, G. A., Frank, J. S. and Zhu, H. (1996). Insulin-like growth factor II induces DNA synthesis in fetal ventricular myocytes in vitro. Circ. Res. 79, 716-726. 10.1161/01.RES.79.4.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P., Wakamiya, M., Shea, M. J., Albrecht, U., Behringer, R. R. and Bradley, A. (1999). Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nat. Genet. 22, 361-365. 10.1038/11932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas, R. G. C., Lee, S., Harakalova, M., Snijders Blok, C. J. B., Goodyer, W. R., Hjortnaes, J., Doevendans, P. A. F. M., Van Laake, L. W., Van Der Velden, J., Asselbergs, F. W.et al. (2021). Massive expansion and cryopreservation of functional human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. STAR Protoc. 2, 100334. 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madonna, R., Van Laake, L. W., Botker, H. E., Davidson, S. M., De Caterina, R., Engel, F. B., Eschenhagen, T., Fernandez-Aviles, F., Hausenloy, D. J., Hulot, J.-S.et al. (2019). ESC working group on cellular biology of the heart: position paper for cardiovascular research: tissue engineering strategies combined with cell therapies for cardiac repair in ischaemic heart disease and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 115, 488-500. 10.1093/cvr/cvz010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, D. and Burkhoff, D. (2005). Mechanical device-based methods of managing and treating heart failure. Circulation 112, 438-448. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.481259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchiano, S., Nakamura, K., Reinecke, H., Neidig, L., Lai, M., Kadota, S., Perbellini, F., Yang, X., Klaiman, J. M., Blakely, L. P.et al. (2023). Gene editing to prevent ventricular arrhythmias associated with cardiomyocyte cell therapy. Cell Stem Cell 30, 396-414.e9. 10.1016/j.stem.2023.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, M. J., Di Rocco, G., Gardiner, A., Bush, S. M. and Lassar, A. B. (2001). Inhibition of Wnt activity induces heart formation from posterior mesoderm. Genes Dev. 15, 316-327. 10.1101/gad.855501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdevitt, T. C., Laflamme, M. A. and Murry, C. E. (2005). Proliferation of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells is mediated via the IGF/PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 865-873. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, H. V., Dawes, T. J. W., Serrani, M., Bai, W., Tokarczuk, P., Cai, J., De Marvao, A., Henry, A., Lumbers, R. T., Gierten, J.et al. (2020). Genetic and functional insights into the fractal structure of the heart. Nature 584, 589-594. 10.1038/s41586-020-2635-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, R. J., Lee, I., Hou, C., Weng, C.-C., Li, S., Lieberman, B. P., Zeng, C., Mankoff, D. A. and Mach, R. H. (2017). Functional screening in human cardiac organoids reveals a metabolic mechanism for cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E8372-E8381. 10.1073/pnas.1703109114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, R. J., Parker, B. L., Quaife-Ryan, G. A., Voges, H. K., Needham, E. J., Bornot, A., Ding, M., Andersson, H., Polla, M., Elliott D. A.et al. (2019). Drug screening in human PSC-cardiac organoids identifies pro-proliferative compounds acting via the mevalonate pathway. Cell Stem Cell 24, 895-907.e6. 10.1016/j.stem.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa, S., kainuma, S., Kawamura, T., Suzuki, K., Ito, Y., Iseoka, H., Ito, E., Takeda, M., Sasai, M., Mochizuki-Oda, N.et al. (2022). Case report: transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte patches for ischemic cardiomyopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 950829. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.950829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, T. M. A., Ang, Y.-S., Radzinsky, E., Zhou, P., Huang, Y., Elfenbein, A., Foley, A., Magnitsky, S. and Srivastava, D. (2018). Regulation of cell cycle to stimulate adult cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac regeneration. Cell 173, 104-16.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, S., Hedjazi, A., Sajjadian, M., Ghoroubi, N., Mohammadi, M. and Erfani, S. (2016). Study of the normal heart size in northwest part of Iranian population: a cadaveric study. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 8, 119-125. 10.15171/jcvtr.2016.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollova, M., Bersell, K., Walsh, S., Savla, J., Das, L. T., Park, S. Y., Silberstein, L. E., Dos Remedios, C. G., Graham, D., Colan, S.et al. (2013). Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1446-1451. 10.1073/pnas.1214608110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, T. O., Hill, M. C., Morikawa, Y., Leach, J. P., Heallen, T., Cao, S., Krijger, P. H. L., De Laat, W., Wehrens, X. H. T., Rodney, G. G.et al. (2019). YAP partially reprograms chromatin accessibility to directly induce adult cardiogenesis In Vivo. Dev. Cell 48, 765-79.e7. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, A. F. M. and Christoffels, V. M. (2003). Cardiac chamber formation: development, genes, and evolution. Physiol. Rev. 83, 1223-1267. 10.1152/physrev.00006.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, A. F., Van Den Berg, G., Anderson, R. H. and Christoffels, V. M. (2010). Early cardiac growth and the ballooning model of cardiac chamber formation. In Heart Development and Regeneration (ed. Rosenthal N. and Harvey R. P.), pp. 219-236. London: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, A., Caron, L., Nakano, A., Lam, J. T., Bernshausen, A., Chen, Y., Qyang, Y., Bu, L., Sasaki, M., Martin-Puig, S.et al. (2006). Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell 127, 1151-1165. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummery, C., Ward-Van Oostwaard, D., Doevendans, P., Spijker, R., Van Den Brink, S., Hassink, R., Van Der Heyden, M., Opthof, T., Pera, M., De La Riviere, A. B.et al. (2003). Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes: role of coculture with visceral endoderm-like cells. Circulation 107, 2733-2740. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068356.38592.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito, H., Melnychenko, I., Didié, M., Schneiderbanger, K., Schubert, P., Rosenkranz, S., Eschenhagen, T. and Zimmermann, W. H. (2006). Optimizing engineered heart tissue for therapeutic applications as surrogate heart muscle. Circulation 114, I72-I78. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivetti, G., Abbi, R., Quaini, F., Kajstura, J., Cheng, W., Nitahara, J. A., Quaini, E., Di Loreto, C., Beltrami, C. A., Krajewski, S.et al. (1997). Apoptosis in the failing human heart. N Engl. J. Med. 336, 1131-1141. 10.1056/NEJM199704173361603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, E. N. (2006). Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart. Science 313, 1922-1927. 10.1126/science.1132292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osafune, K., Caron, L., Borowiak, M., Martinez, R. J., Fitz-Gerald, C. S., Sato, Y., Cowan, C. A., Chien, K. R. and Melton, D. A. (2008). Marked differences in differentiation propensity among human embryonic stem cell lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 313-315. 10.1038/nbt1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani, D., Ter Huurne, M., Elliott, D. A., Bellin, M. and Mummery, C. L. (2023). Maturing differentiated human pluripotent stem cells in vitro: methods and challenges. Development 150, dev201103. 10.1242/dev.201103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paige, S. L., Osugi, T., Afanasiev, O. K., Pabon, L., Reinecke, H. and Murry, C. E. (2010). Endogenous Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for cardiac differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 5, e11134. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paige, S. L., Plonowska, K., Xu, A. and Wu, S. M. (2015). Molecular regulation of cardiomyocyte differentiation. Circ. Res. 116, 341-353. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.302752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, T. G., Packer, S. E. and Schneider, M. D. (1990). Peptide growth factors can provoke ‘fetal’ contractile protein gene expression in rat cardiac myocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 85, 507-514. 10.1172/JCI114466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, S., Agius, E., Leyns, L., Bhattacharyya, S., Grunz, H., Bouwmeester, T. and De Robertis, E. M. (1999). The head inducer cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of nodal, BMP and Wnt signals. Nature 397, 707-710. 10.1038/17820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski, P., Voors, A. A., Anker, S. D., Bueno, H., Cleland, J. G. F., Coats, A. J. S., Falk, V., González-Juanatey, J. R., Harjola, V.-P., Jankowska, E. A.et al. (2016). 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail 18, 891-975. 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrello, E. R., Mahmoud, A. I., Simpson, E., Hill, J. A., Richardson, J. A., Olson, E. N. and Sadek, H. A. (2011). Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science 331, 1078-1080. 10.1126/science.1200708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptaszek, L. M., Mansour, M., Ruskin, J. N. and Chien, K. R. (2012). Towards regenerative therapy for cardiac disease. Lancet 379, 933-942. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60075-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qyang, Y., Martin-Puig, S., Chiravuri, M., Chen, S., Xu, H., Bu, L., Jiang, X., Lin, L., Granger, A., Moretti, A.et al. (2007). The renewal and differentiation of Isl1+ cardiovascular progenitors are controlled by a Wnt/β-Catenin pathway. Cell Stem Cell 1, 165-179. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochais, F., Mesbah, K. and Kelly, R. G. (2009). Signaling pathways controlling second heart field development. Circ. Res. 104, 933-942. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungarunlert, S., Techakumphu, M., Pirity, M. K. and Dinnyes, A. (2009). Embryoid body formation from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells: benefits of bioreactors. World J. Stem Cells 1, 11-21. 10.4252/wjsc.v1.i1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga, Y., Pulkki, K., Kallajoki, M., Henriksen, K., Parvinen, M. and Voipio-Pulkki, L.-M. (1999). MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development 126, 3437-3447. 10.1242/dev.126.15.3437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraste, A., Pulkki, K., Kallajoki, M., Henriksen, K., Parvinen, M. and Voipio-Pulkki, L.-M. (1997). Apoptosis in human acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 95, 320-323. 10.1161/01.CIR.95.2.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade, D., Drowley, L., Wang, Q. D., Plowright, A. T. and Greber, B. (2022). Phenotypic screen identifies FOXO inhibitor to counteract maturation and promote expansion of human iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 65, 116782. 10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, V. A. and Mercola, M. (2001). Wnt antagonism initiates cardiogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Genes Dev. 15, 304-315. 10.1101/gad.855601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker, S. and Smith, J. C. (1995). Mesoderm formation in response to brachyury requires FGF signalling. Curr. Biol. 5, 62-67. 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00017-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera, D. and Thompson, R. P. (2011). Myocyte proliferation in the developing heart. Dev. Dyn. 240, 1322-1334. 10.1002/dvdy.22650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A., Mckeithan, W. L., Serrano, R., Kitani, T., Burridge, P. W., Del Álamo, J. C., Mercola, M. and Wu, J. C. (2018a). Use of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes to assess drug cardiotoxicity. Nat. Protoc. 13, 3018-3041. 10.1038/s41596-018-0076-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A., Zhang, Y., Buikema, J. W., Serpooshan, V., Chirikian, O., Kosaric, N., Churko, J. M., Dzilic, E., Shieh, A., Burridge, P. W.et al. (2018b). Stage-specific effects of bioactive lipids on human iPSC cardiac differentiation and cardiomyocyte proliferation. Sci. Rep. 8, 6618. 10.1038/s41598-018-24954-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L., Jhund, P. S., Docherty, K. F., Vaduganathan, M., Petrie, M. C., Desai, A. S., KøBer, L., Schou, M., Packer, M., Solomon, S. D.et al. (2022). Accelerated and personalized therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 43, 2573-2587. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Y., Fernandes, S., Zhu, W.-Z., Filice, D., Muskheli, V., Kim, J., Palpant, N. J., Gantz, J., Moyes, K. W., Reinecke, H.et al. (2012). Human ES-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature 489, 322-325. 10.1038/nature11317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Y., Gomibuchi, T., Seto, T., Wada, Y., Ichimura, H., Tanaka, Y., Ogasawara, T., Okada, K., Shiba, N., Sakamoto, K.et al. (2016). Allogeneic transplantation of iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerates primate hearts. Nature 538, 388-391. 10.1038/nature19815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A., Ramesh, S., Cibi, D. M., Yun, L. S., Li, J., Li, L., Manderfield, L. J., Olson, E. N., Epstein, J. A. and Singh, M. K. (2016). Hippo signaling mediators Yap and Taz are required in the epicardium for coronary vasculature development. Cell Rep. 15, 1384-1393. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. C., Price, B. M., Green, J. B., Weigel, D. and Herrmann, B. G. (1991). Expression of a Xenopus Homolog of Brachyury (T) is an immediate-early response to mesoderm induction. Cell 67, 79-87. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90573-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares, F. A. C., Chandra, A., Thomas, R. J., Pedersen, R. A., Vallier, L. and Williams, D. J. (2014). Investigating the feasibility of scale up and automation of human induced pluripotent stem cells cultured in aggregates in feeder free conditions. J. Biotechnol. 173, 53-58. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Später, D., Abramczuk, M. K., Buac, K., Zangi, L., Stachel, M. W., Clarke, J., Sahara, M., Ludwig, A. and Chien, K. R. (2013). A HCN4+ cardiomyogenic progenitor derived from the first heart field and human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 1098-1106. 10.1038/ncb2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamos, J. L. and Weis, W. I. (2013). The β-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 5, a007898. 10.1101/cshperspect.a007898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, E. G., Biben, C., Elefanty, A., Barnett, L., Koentgen, F., Robb, L. and Harvey, R. P. (2002). Efficient Cre-mediated deletion in cardiac progenitor cells conferred by a 3'UTR-Ires-Cre Allele of the Homeobox Gene Nkx2-5. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46, 431-439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturzu, A. C., Rajarajan, K., Passer, D., Plonowska, K., Riley, A., Tan, T. C., Sharma, A., Xu, A. F., Engels, M. C., Feistritzer, R.et al. (2015). Fetal mammalian heart generates a robust compensatory response to cell loss. Circulation 132, 109-121. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]