Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

Summary of changes: Introduction: we (a) clarified the role of mainstream policy theory and (b) summarised the health equity strategy (HiAP) used as a comparison with education equity policy (pp3-6) Methods: we clarified the (a) role of the IMAJINE project’s research questions and approach, (b) importance of immersion and induction, (c) coding, and (b) approach to analysis and synthesis (pp6-9) Results: we altered subheadings and formatting to address the lack of clarity of some parts of the presentation. We edited this section to reduce the word count (to accommodate changes prompted by each reviewer) (pp10-35). Conclusion: we reorganized and improved the discussion on policy and research implications (pp39-40). A full account of these changes can be found in the reply to reviewers.

Abstract

Background: COVID-19 had a major global impact on education, prompting concerns about its unequal effects and some impetus to reboot equity strategies. Yet, policy processes exhibit major gaps between such expectations and outcomes, and similar inequalities endured for decades before the pandemic. Our objective is to establish how education researchers, drawing on policy concepts and theories, explain and seek to address this problem.

Methods: A qualitative systematic review (2020-21), to identify peer reviewed research and commentary articles on education, equity, and policymaking, in specialist and general databases (ERIC, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane/ Social Systems Evidence). We did not apply additional quality measures. We used an immersive and inductive approach to identify key themes. We use these texts to produce a general narrative and explore how policy theory articles inform it.

Results: 140 texts (109 articles included; 31 texts snowballed) provide a non-trivial reference to policymaking. Limiting inclusion to English-language produced a bias towards Global North articles. Our comparison with a review of health equity research highlights distinctive elements in education. First, education equity is ambiguous and contested, with no settled global definition or agenda (although some countries and international organisations have disproportionate influence). Second, researchers critique ‘neoliberal’ approaches that dominate policymaking at the expense of ‘social justice’. Third, more studies provide ‘bottom-up’ analysis of ‘implementation gaps’. Fourth, more studies relate inequity to ineffective policymaking to address marginalised groups.

Conclusions: Few studies use policy theories to explain policymaking, but there is an education-specific literature performing a similar role. Compared to health research, there is more use of critical policy analysis to reflect on power and less focus on technical design issues. There is high certainty that current neoliberal policies are failing, but low certainty about how to challenge them successfully.

Keywords: Policymaking, Education, Equity, Race, Complexity, Critical policy analysis

Plain language summary

Governments and international organisations have made a longstanding commitment to education equity. Rebooted initiatives to incorporate the additional unequal impact of COVID-19 are possible, but policymaking research highlights likely obstacles to their progress.

First, equity is vague and there are many competing ‘education equity’ initiatives. International agendas focus on: shifting resources towards early years education; delivering a minimum level of schooling and making school environments more inclusive, to address the links between attainment and social and economic background (including class, gender, race, and ethnicity); comparing the performance of school systems, including their ability to reduce inequalities of attainment; and, widening access to further and higher education (FE/HE).

Second, there is a continuous gap between expectations and outcomes. A ‘top down’ perspective, through the lens of international organisations or central governments, highlights implementation gaps. A ‘bottom up’ perspective, through the lens of local or school leaders, highlights an inability to make progress without understanding how people make sense of equity as they deliver policy.

Third, many possible outcomes can emerge in a complex policymaking system. The competition to define equity produces different agendas competing for resources. The ‘neoliberal’ performance management agenda narrows equity to a measure of school access or exam outcomes, while seeking ‘equity for all’. ‘Social justice’ approaches address underlying causes of inequalities, focusing in particular on marginalised groups. International, national, and subnational policymakers make sense of these agendas in different ways, and there is some ability for local policymakers to reinterpret central government initiatives.

Overall, educational equity policymaking involves the exercise of power to decide what equity means, who matters, how to deliver policy, and who benefits. A technical focus on rebooting initiatives and closing implementation gaps does not guarantee success and overshadows the need to address wider determinants of education outcomes.

Introduction

We present a qualitative systematic review of education equity policy research. The review describes the contested nature and slow progress of education equity agendas, how education research tries to explain it, and how the use of policy process research might help. The reviewed research was published before the global pandemic. However, the impact of COVID-19 is impossible to ignore because it has highlighted and exacerbated education inequity (defined simply as unfair inequalities). New sources include the unequal impact of ‘lockdown’ measures on physical and virtual access to education services (from pre-primary to higher education), often exacerbated by rewritten rules on examinations ( Kippin & Cairney, 2021). The COVID-19 response has also highlighted the socio-economic context where only some populations have the ability to live and learn safely.

This new international experience could prompt a major reboot of global and domestic education equity initiatives. It is tempting to assume that high global attention to inequalities will produce a ‘window of opportunity’ for education equity initiatives. However, policymaking research warns against the assumption that major and positive policy change is likely. Further, equity policy research shows that policy processes contribute to a major gap between vague expectations and actual outcomes ( Cairney & St Denny, 2020). Crises could prompt policy choices that exacerbate the problem. Indeed, the experience of health equity policy is that the COVID-19 response actually undermined a long-term focus on the social and economic causes of inequalities ( Cairney et al., 2021).

Therefore, advocates and researchers of education policy reforms need to draw on policymaking research to understand the processes that constrain or facilitate equity-focused initiatives. In particular, we synthesise insights from ‘mainstream’ policy theories to identify three ever-present policymaking dynamics (see Cairney, 2020: 229–34). First, most policy change is minor, and major policy changes are rare. Second, policymaking is not a rationalist ‘evidence based’ process. Rather, policymakers deal with ‘bounded rationality’ ( Simon, 1976) by seeking ways to ignore almost all information to make choices. Third, they operate in a complex policymaking environment of which they have limited knowledge and control. Without using these insights to underpin analysis, equity policy research may tell an incomplete story of limited progress and address ineffectively the problem it seeks to solve.

We designed this study as a partner to the review of the international health equity strategy Health in All Policies (HiAP) ( Cairney et al., 2021) to produce reviews of equity research in different policy sectors. The pursuit of major policy change, to foster more equitable processes and outcomes, is impossible to contain within one sector, and comparison is crucial to our understanding of intersectoral policymaking (explored in Cairney et al., 2022). Indeed, the HiAP review reveals a tendency for researchers to use policy theories instrumentally, and superficially, to that end. They seek practical lessons to help advocate more effectively for policy change in multiple policy sectors and improve intersectoral coordination to implement HiAP. As Cairney et al., 2021 describe, most policy theories were not designed for that purpose. Rather, they are more useful to (1) identify the limits to change in policy and policymaking, then (2) encourage equity advocates to engage with complex political dilemmas rather than seek simple technical fixes to implementation gaps.

We did not expect to replicate the HiAP study entirely, since – for example - the terminology to describe policy aims and processes is not consistent across sectors, and the most-studied countries differ in each sector. Rather, we emulate the method for searching for articles: using broadly comparable search terms, while recognising that there is no direct education equivalent to HiAP; and, using the same broad focus on policy theories to guide inclusion. Then, we highlight key sectoral differences and use them to structure our initial analysis. As our Results section shows, the health/ education equity comparison prompts us to:

1. Establish if there is a coherent international education policy agenda to which each article contributes.

The HiAP story is relatively coherent and self-contained, identifying the World Health Organization (WHO) ‘starter’s kit’ and playbook. HiAP research supports that agenda ( Cairney et al., 2021). In education, initiatives led by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) have some comparable elements. However, there are (1) more international players with high influence, including key funders such as the World Bank and agenda setters such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and (2) more important reference points for domestic studies. In particular, US studies are relatively self-contained - examining the connection between federal, state, and local programmes – and the US model of education equity is a reference point for international studies.

2. Analyse the contested definition of equity: what exactly does it mean?

Equity is an ambiguous and contested term. In political systems, actors exercise power to resolve policy ambiguity in their favour: to determine who is responsible for problem definition and who benefits from that definition. This contestation over meaning plays out in different ways in different sectors. The HiAP story contains the same basic treatment of equity as the avoidance of unfair health inequalities caused by ‘social determinants’ such as unequal incomes and wealth, access to high quality education, secure and well-paid jobs, good housing, and safe environments. This approach is part of a political project to challenge a focus on individual lifestyles and healthcare services. Few HiAP studies interrogate this meaning of equity before identifying a moral imperative to pursue it, although most find that policymakers do not share their views ( Cairney et al., 2021).

In education, the exercise of power is a central feature of research: equity is highly contested, there is no equivalent agreement that all inequalities are unfair, and fewer studies examine the ‘social determinants’ of education inequalities. Far more studies criticise how policymakers (a) ignore ‘social determinants’ and (b) defend a more limited definition of equity as the equal opportunity to access a high-quality public service (the meaning of terms such as ‘quality’ are also contested – see Ozga et al., 2011).

3. Explore critiques of ‘neoliberal’ approaches to education equity.

Common descriptions of neoliberalism refer to two related factors. First, policymaking based on a way of thinking that favours individualism and non-state solutions, and therefore prioritises individual over communal or state responsibility, market over state action, and/or quasi-markets for public services (a competition to deliver services, designed and regulated by governments). For example, Rizvi (2016: 5) describes ‘a mode of thinking that disseminates market values and metrics to every sphere of life and constructs human beings and relations largely in economic terms’. A neoliberal approach to education equity would emphasise individual student motivation, quasi-market incentives such as school vouchers, and limited state spending in favour of private for-profit provision. Second, giving relative priority to policies to ensure economic growth, with education treated as facilitating a ‘global knowledge economy’ rather than a wider social purpose ( Rizvi & Lingard, 2010: 39–41; Wiseman & Davidson, 2021: 2–3).

The damaging effect of neoliberal approaches – including their highly unequal effects within and across countries - is a central theme in health and education research. Health studies generally describe experiences of high HiAP commitment undermined by a neoliberal economic agenda. Two-fifths of education articles focus on the United States and more describe the US as an international reference point. US education equity policy supports a model built on closing an ‘achievement gap’ via quasi-markets, quality improvement, performance management, and measuring the gap narrowly with standardised test scores. The US contributes disproportionately (alongside international organisations like the World Bank) to a limited focus on social determinants in favour of seeing education as an investment in human capital. While health studies analyse neoliberalism as an external disruptor to HiAP, education research centres and problematises it, to understand its tendency to constrain the equity efforts of national and local policy actors.

4. Compare top-down and bottom-up perspectives on policymaking complexity.

HiAP has a top-down focus, identifying the extent to which a policy agenda is implemented in different contexts. Few studies focus on health services, assuming that the biggest determinants of health are outside of healthcare. Education studies have a relatively bottom-up focus, identifying a national policy agenda as key context, but also local venues where actors make policy as they deliver. There is a greater focus on ‘sense making’ among school leaders.

5. Identify the impact of minoritization and marginalisation.

Education studies are more likely to centre race and racism, often using ‘critical policy analysis’ (research to defend marginalised populations when analysing policy problems and proposing solutions). These issues are not absent in HiAP research ( Baum et al., 2019; Bliss et al., 2016; Corburn et al., 2014; see also D’Ambruoso et al., 2021; Selvarajah et al., 2020). However, the included education studies have a greater focus on minoritization (the social construction of minority groups, and the rules to treat them in a different way from a dominant majority) and the equity initiatives that – intentionally and unintentionally - fail to address race and racism.

Our Discussion section relates these Results to the three key insights – on policy change, bounded rationality, and policymaking complexity – that we attribute to policymaking concepts and theories. We describe these general insights more fully and show how a small subset of included articles uses them to explain education policy dynamics. We show how policy concepts and theories can – and sometimes do - inform the study of education equity policy. First, they highlight the general difference between education equity policy on paper and in practice. Second, they show how policymakers deal with bounded rationality by: (a) paying minimal attention to key equity issues; (b) relying on actors who share their beliefs; (c) emulating other governments without understanding their alleged success; and (d) basing policy on social stereotypes, while (e) describing their choices as ‘evidence based’. Third, they explain how complex policymaking environments mediate policy change. In the Conclusion, we show that these insights contribute to a commonly told story in education equity research: there is high rhetorical but low substantive commitment to reducing unfair inequalities, and the dominant neoliberal approach undermines the social justice approaches that are essential to policy progress.

Methods

We are conducting these reviews as part of the Horizon 2020 project Integrative Mechanisms for Addressing Spatial Justice and Territorial Inequalities in Europe (IMAJINE). The project’s general aim is to identify how policymakers and researchers understand the concept of ‘spatial justice’ and seek to reduce ‘territorial inequalities’. Our role is to relate that specific focus to a wider context, to examine how (a) policy actors compete to define the policy problem of equity or justice in relation to inequalities, and (b) how they identify priorities in relation to factors such as geography, gender, class, race, ethnicity, and disability. Our general focus in IMAJINE reviews is:

-

1.

What is the policy problem? Specifically, what is equity, and what constrains or facilitates its progress?

-

2.

How does it relate to policy processes? Do articles identify a lack of policy progress and how to address it? What policy theories do they use when describing policymaking?

In that context, each review’s guiding question is: How does equity research use policy theory to understand policymaking?

Originally, we identified five sub-questions to guide article inclusion (Q1) and analysis (Q2-5):

-

1.

How many studies provide a non-trivial reference to policymaking concepts or theories?

-

2.

How do these studies describe policymaking?

-

3.

How do these studies describe the ‘mechanisms’ of policy change that are vital to equity strategies (although Cairney et al., 2021 show that very few studies answer this question)?

-

4.

What transferable lessons do these studies provide? For example, what lessons for other governments do case studies provide?

-

5.

How do these studies relate educational equity to concepts such as spatial justice?.

We answer that full set of questions elsewhere, in relation to inequalities policies across the EU ( Cairney et al., 2022). Here, we focus on making sense of the general project in the specific sector of education, To that end, we use a period of immersion to learn from this field, rather than impose too-rigid questions and quality criteria that would limit interdisciplinary and intersectoral dialogue.

First, we initially use a flexible interpretation of Q1 to guide article inclusion. As Cairney et al. (2021) describe, our reviews set a lower bar for inclusion than comparable studies, based on previous work showing that a wide search parameter and low inclusion bar (in relation to relevance, not quality) does not produce an unmanageable number of articles to read fully. High inclusion helps us to generate a broad narrative of the field, identify a sub-set of the most policy theory-informed articles, and examine how the sub-set enhances that narrative.

Second, we initially searched fewer databases than Cairney et al. (2021). This strategy allowed us to use snowballing to generate core references identified by authors of included articles. This process is crucial to researchers relatively new to each discipline, and unsure if the search for particular theories or concepts makes sense. We also searched each database sequentially to use feedback from each search to refine the next and pursue a sense of saturation. Initially, we used the education-specific database Institute of Education Services (ERIC) in 2020 (search ran from 18/10/20 to 20/12/20). We used these search terms: ‘education’, ‘equity’, and ‘policy’, with no additional filters, then searched manually for articles providing one or more references to (a) the ‘policy cycle’ (or a particular stage, such as agenda setting or implementation), (b) a mainstream policy theory, such as multiple streams, the advocacy coalition framework, punctuated equilibrium theory, or concept, such as variants of new institutionalism, or (c) critical policy analysis (we used Cairney, 2020 for a list of mainstream theories and concepts, summarised on Cairney’s blog; see also Durnova & Weible, 2020 on mainstream and critical approaches).

These terms are broadly comparable to the health equity search terms, but there is no direct equivalent to HiAP or the WHO as its champion. UNESCO is broadly equivalent to the WHO, but to focus on a UNESCO initiative alone would be misleading: the WHO features in almost-all HiAP studies, but UNESCO is discussed less frequently than the World Bank or OECD in education studies. Since this context is crucial for multiple review comparison, we describe it at the beginning of our Results (‘The policymaking context: how international organisations frame equity’).

We used similar criteria for inclusion as Cairney et al. (2021). The article had to be published in a peer reviewed journal in English (research and commentary articles), and provide at least one reference to a conceptual study of policymaking in its bibliography. To prioritise immersion, we erred on the side of inclusion if articles cited education policymaking texts (e.g. rather than the original policy theory source). This focus on articles alone seems more problematic in education, so we used snowballing to identify 31 exemplar texts described as foundational. Education research has its own frames of reference regarding: ‘policy sociology’ (half of the included articles feature Ball, e.g., Ball, 1993; Ball, 1998; Ball et al., 2011), policy borrowing (e.g., Rizvi & Lingard, 2010; Steiner-Khamsi, 2006; Steiner-Khamsi, 2012), policy implementation (e.g., Spillane et al., 2002), and performance management (e.g., Ozga et al., 2011). Most articles describe concepts such as policy transfer without relying on the mainstream policy theory literature ( Cairney, 2020), but, for example, Rizvi & Lingard (2010) and Steiner-Khamsi (2012) perform this function.

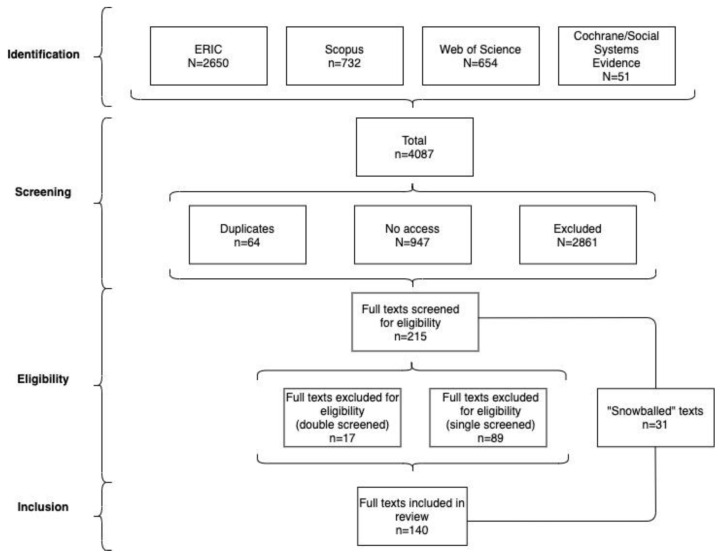

Third, this initial approach – inclusion, immersion, snowballing – allowed us to establish the often-limited relevance of articles with a trivial reference to policy concepts. We could then pursue a more restrictive approach to subsequent searches: using the same search terms (education*, equit*, policymak*) and no additional filters, but erring towards manual exclusion when the article had a superficial discussion of policymaking. Searches of Cochrane/ Social Systems Evidence database (01/06/21 – 02/06/21), Scopus (29/03/21 – 23/04/21), and Web of Science (05/05/21 – 27/05/21), found 26 additional texts before we reached saturation. Table 1 and Figure 1 summarise these search results.

Figure 1. Review process flow chart.

Table 1. Search results 2020/21.

| Database | Search results | Duplicates | No access | Excluded at

any stage |

Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERIC | 2650 | 2 | 519 | 2046 | 83 |

| Scopus | 732 | 21 | 215 | 483 | 13 |

| Web of Science | 654 | 41 | 213 | 390 | 10 |

|

Cochrane/

Social Systems Evidence |

51 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 3 |

| Total | 4087 | 64 | 947 | 2967 | 109 |

Kippin carried out the initial ERIC screening, producing a long list - erring on the side of inclusion - based on the title, abstract, bibliographies, and a manual search to check for the non-trivial use of ‘policymaking’ in the main body of the text. Cairney performed a further inclusion check on the long list, based on a full reading of the article (to extract data as part of the review), referring some articles back to double check for exclusion. Cairney and Kippin double-screened 17 borderline cases during the final eligibility phase (using full-text analysis). In this stage, we excluded 10 borderline cases but included seven that provided a comparable study of policymaking without citing mainstream policy theories. In total, 83 articles are included from ERIC ( Figure 1). The same process yielded three articles (one excluded) from Cochrane/ Social Systems Evidence databases, 13 (two) from Scopus, and 10 (two) from Web of Science.

Fourth, we sought to ‘map’ our field by coding the following aspects of each article (in an Excel spreadsheet):

Country/region of study. 43% of studies focused on the US, 9% Canada, 8% Nordic countries, and 7% Australia. 15% described multi-country studies.

Country of author affiliation. 50% of first authors were listed as affiliated with organisations in the US, 14% Canada, 14% Australia, and 7% Nordic countries.

Policy or case study issue. Nearly all described compulsory primary and/or secondary education (91%) or Higher Education (HE) (6%). 3% were ‘other’ (e.g., vocational education or system-wide studies).

Research methods. Studies used semi-structured interviews with policy participants (28%), document analysis (16%), surveys and statistical analysis (8%), discourse/narrative analysis (7%), ‘systematic’ or ‘rigorous’ reviews (5%), case study methods (5%), content analysis (4%), participant observation (4%) or other methods (2%). 21% did not describe a research method.

Article type. Included texts were research articles or reviews (83%) or commentary articles (17%).

We consolidated this process into fewer categories after learning from the HiAP review - Cairney et al. (2021) - that too few articles addressed our questions on the ‘mechanisms’ of policy change (Q3), transferable lessons (Q4), or space/ territory (Q5). We also gathered information on three questions whose answers were not conducive to spreadsheet coding:

-

1.

How do the authors (or their subjects) define equity? (summarised below, in ‘Policy ambiguity: the competition to define and deliver equity’).

-

2.

What, if any, are their policy recommendations? (summarised below, in ‘2. Competing definitions and alternative researcher aspirations’).

-

3.

On what policy concepts and theories do they draw (and cite)? Compared to HiAP, we found (a) a greater focus on critical policy analysis to problematise how policymakers define problems and seek solutions, and (b) almost no equivalent to the instrumental use of policy theories (except Eng, 2016).

Fifth, we used an inductive qualitative approach to analyse each text, generate themes (Results), and relate them to policy theory insights (Discussion). The rules associated with this method are less prescriptive than with its quantitative equivalent, suggesting that we (a) describe each key judgement (as above), and (b) foster respect for each author’s methods and aims ( Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007: xv). The unusually generous word limits in ORE allow us to devote considerable space to key articles. To that end, in a separate Word document, we produced a (300-400 word) summary of the ‘story’ of each article: identifying its research question, approach, substantive findings, and take-home messages; and, connecting each article to emergent themes, including the contestation to define education equity, and the uneasy balance between centralised and decentralised approaches to policymaking. We condensed and used most summaries to construct a series of thematic findings (Results), then integrated the sub-set of mainstream theory-informed articles with our synthesis of policy theory insights (Discussion).

The complete search protocol is stored on the OSF ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BYN98) ( Cairney & Kippin, 2021).

Results

The policymaking context: how international organisations frame equity

Education equity policy is contested, producing multiple competing agendas. Yet, most articles identify a tendency for one approach to dominate in relation to (1) global equity initiatives and (2) the impact of international agendas on domestic policy. Therefore, we first describe the wider international context in which most articles are situated. Throughout, we use a comparison with HiAP ( Cairney et al., 2021) to note the relative absence of a single equity agenda in education.

Global equity initiatives

On the one hand, as with HiAP, there is a well-established global agenda championed by an UN organisation. UNESCO’s approach to education is often similar to the WHO approach to HiAP (see Cairney et al., 2021). Broad comparable aims include:

Treat education as a human right, backed by legal and political obligations ( UNESCO, 2021b).

Foster inclusion and challenge marginalisation ‘on the basis of socially-ascribed or perceived differences, such as by sex, ethnic/social origin, language, religion, nationality, economic condition, ability’ ( UNESCO, 2021a).

Foster gender equality, to address major gaps in access to education ( UNESCO, 2021c).

Boost early education (0–8 years) as the biggest influence on human development and most useful investment ( Marope & Kaga, 2015; UNESCO, 2021d).

Boost the mutually-reinforcing effect of education and health ( UNESCO, 2021e).

Boost global capacity ( UNESCO, 2021f).

‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ (UN Sustainable Development Goal 4, SDG4).

On the other hand, there are competing narratives on what equity means in this context, including:

-

1.

The primary purpose of education: (a) as training for work, as part of an economic ‘human capital’ narrative (supported by ‘donor’ organisations such as the World Bank, and country government organisations such as United States Agency for International Development, USAID); or (b) to foster student emancipation, wellbeing, and life opportunities (supported by education researchers and practitioners) ( Faul, 2014; Vongalis-Macrow, 2010).

-

2.

The meaning of ‘education for all’: shifting since 1990 to treating education solely as schooling (and prioritising targets for primary schools), and changing the meaning of ‘for all’, “from encompassing all countries to developing countries only; from ‘all’ to children only; and from being a responsibility of all members of the international community to being a responsibility of governments to their citizens alone” ( Faul, 2014: 13–14; Gozali et al., 2017: 36).

-

3.

Narratives of inclusion: including the UNESCO Salamanca statement on inclusive special needs education, global commitments to education for girls, and some focus on the ‘social determinants’ of learning related to class, race, ethnicity and marginalisation, or the need for multicultural education to challenge racism and xenophobia ( Engsig & Johnstone, 2015; Faul, 2014: 15; Lopez, 2017).

-

4.

Narratives of high ‘quality’ education: including a greater focus on reading and mathematics, with limited support for ‘the role of education in broad social issues and its intrinsic value’ ( Faul, 2014: 16).

-

5.

Who should deliver education: the public or private provision of services.

As Faul (2014: 16) describes, approaches to these questions fall into two broad categories:

1. An economic approach supported by performance management (fostered by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and countries such as the US). It measures learning in relation to test-measured outcomes, facilitated by techniques associated with new public management (NPM), privatization and the mantra of ‘evidence based’ policy. Klees & Qargha (2014: 324–5) argue that this ‘cheap fix’ approach exacerbates inequalities while pretending to reduce them. The analysis of results is contested in areas such as ‘performance pay for teachers, low-cost private schools, teacher training, conditional cash transfers, and most other studies of impact’ (2014: 329; see also Tobin et al., 2016: 583 on large scale assessments).

2. A human rights and social determinants approach (fostered by UNICEF and UNESCO). A ‘rights-based, social justice argument calls for universal investment in quality education regardless of its impact’ ( Klees & Qargha, 2014: 330). UNICEF (a) supports an approach to address the ‘deeply entrenched structural inequalities and disparities’ which keep ‘children out of school’, but (b) often vaguely, while diluting its language by referring to cost-effectiveness (2014: 326–7; 330–1).

The former approach dominates international policymaking, prioritising literacy and numeracy, and measuring access in narrow ways (e.g., ‘gender parity’ as ‘equal numbers of boys and girls in school’, 2014: 17). The latter receives rhetorical support without being backed by concrete measures (and UNESCO policy statements come with descriptions of limited progress). There is also a tendency towards technocracy, with limited democratic and participatory processes to help define policy ( Klees & Qargha, 2014: 331).

Consequently, narratives of long-term development describe progress in global education, but unequal progress, with a warning against one-size-fits-all approaches to access ( Reimers et al., 2012). Klees & Qargha (2014: 321–3) identify a gap between global rhetoric and actual practices regarding Education for All (EFA, which preceded SDG4). The Universal Primary Education (UPE) commitment has existed since the 1960s, but there is no prospect of the equivalent for secondary education (2014: 322), suggesting that: ‘these efforts have not been sufficiently serious’ (2014: 325–6). The gap relates partly to the alleged trade-offs, such as with efficiency or quality, that undermine support for equity (2014: 324). There are also many international organisation initiatives (including USAID on reading skills; World Bank Learning for All, Brookings Institution Global Compact for Learning) and initiatives funded by corporate or philanthropic bodies, each with their own definitions, motivations, and measures ( Tarlau & Moeller, 2020).

This story infuses most comparative studies. For example, Vaughan’s (2019: 494–6) discussion of financial support for gender-based education equity identifies shifts in focus, including: on women’s rights (up to 1990), equal access to schools (1990–2010), and ‘gender-based violence’ and other social factors that undermine equality (a patchy focus since 2010). A rise in attention has generated new opportunities for women’s rights groups and social movements to influence policy (2019: 500–8), but has not prompted a shift from the dominant economic frames of equity supported by ‘multilaterals, bilateral agencies, national governments and more recently, private sector organisations’ (2019: 494). These organisations measure ‘gender disparities in access, attendance, completion and achievement’, drawing ‘heavily on human capital perspectives concerned with the economic significance of getting girls into school, particularly in terms of poverty reduction’ (2019: 509; 496). This focus on a ‘business case’ for policy minimises attention to the marginalisation of girls within schools and the need to reform systems to ‘properly change how schooling relates to gender inequalities in the labour market, political participation, and levels of violence against women’ (2019: 509–10; 496).

Literature reviews - commissioned by development agencies on ‘developing countries’ - also identify patchy evidence and limited progress ( Kingdon et al., 2014 and Novelli et al., 2014 are for the UK Department for International Development; Best et al., 2013 is for Australian Agency for International Development). Kingdon et al.’s (2014) ‘rigorous review of the political economy of education systems in developing countries’ finds that the putative benefits of (neoliberal international donor-driven) education decentralisation ‘do not accrue in practice’, particularly in rural areas (in e.g., Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mexico, Indonesia, Ghana) (2014: 2; 28–9). Best et al. (2013: 65) find that ‘Almost two-thirds of all developing countries have participated in a national, regional or international assessment programme’, but find minimal evidence of their impact. Novelli et al. (2014: 40–2) describe the amplification of problems in ‘conflict affected contexts’, where security actors overshadow humanitarian actors and education specialists are marginalised. In that context, global agendas on access to school have a ‘one size fits all’ feel (e.g., Nepal), the prioritisation of post-conflict economic growth and education efficiency/ decentralization often exacerbates material and educational inequalities (e.g., El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras), a focus on equity in relation to citizenship often distracts from inequitable allocations of resources (e.g., Sri Lanka), and the insistence on free primary education obliges large private sector expansion (e.g., Rwanda).

International agendas on equity, performance, and quality in education

Many organisations seek to measure and promote improved performance in education systems and schools as the main vehicle for equity. The OECD is particularly influential ( Grek, 2009: 24; Grek, 2020; Rizvi & Lingard, 2010: 128–36). It has a wide remit, engaging with multiple definitions of equity and ways to achieve it, despite being associated with a focus on education system performance management via international testing programmes such as PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment). Key reports describe education equity in relation to human rights and socio-economic factors; education is a basic necessity that boosts health, wellbeing, citizenship, and economies ( Field et al., 2007: 11; 33; OECD, 2008: 1). The OECD ( OECD (2008); OECD (2012); ( Field et al., 2007: 11; 31, drawing on Levin, 2003) relates equity to:

-

1.

Fairness (social background should not obstruct education potential), inclusion (everyone should reach a minimum standard), and opportunity (to receive education and succeed at school) ( OECD, 2008: 2).

-

2.

The imperative to address unfair inequalities. There remains a gap between ambitions and outcomes, and major inequalities of attainment endure in relation to poverty, migration, and minoritization ( Field et al., 2007: 3; OECD, 2008: 2).

-

3.

Costs. Inequalities have individual costs (relating to income, citizenship, and the ability to learn) and social costs (including economic stagnation and public service costs) ( OECD, 2012: 3; Field et al., 2007: 33).

It also sets international policy agendas, identifying the ability of (a) good school performance, and (b) the distribution of education spending (in favour of early years over higher education) to mitigate against socio-economic inequality ( Field et al., 2007: 22; 39; OECD, 2012: 9; 3; OECD, 2008: 2; 6–7; OECD, 2015: 1–2).

Overall, the OECD relates inequitable outcomes to ‘deprived backgrounds’ and ‘weak schooling’ ( Field et al., 2007: 26). It recognises the ‘lack of fairness’ caused by the unequal impact of ‘socio-economic background’ on school completion and attainment (2012: 9), and has some HiAP-style emphasis on cross-sectoral working and supportive social security: ‘education policies need to be aligned with other government policies, such as housing or welfare, to ensure student success’ (2012: 10). However, it does not share with HiAP the sense that all unequal outcomes are unfair and require state intervention, since some relate to individual motivation and potential ( Levin, 2003: 5, cited in Field et al., 2007: 31). Levin (2003: 8) describes a balance between ‘equality of opportunity’ and equitable outcomes in skills attainment and employability. Nor do they support the HiAP focus on ‘upstream’ whole-population measures ( Cairney et al., 2021). Rather, equity is the fair distribution of good education services, on the expectation that education can largely solve inequities relating to a minimum threshold of attainment ( Field et al., 2007: 26). This focus on ‘helping those at the bottom move up’ is ‘workable from the standpoint of policy’ ( Field et al., 2007: 31; 46–51; Levin, 2003: 5).

In that context, the OECD makes the following recommendations:

-

1.

Foster the equitable distribution of budgets. Prioritise funding for high quality early education, free or reduced-fee education, and reducing regional disparities ( Field et al., 2007: 23; 122–6; OECD, 2012: 3–11; 117–8; OECD, 2008: 5; OECD, 2015).

-

2.

Foster multiculturalism and antiracism. Foster a ‘multicultural curriculum’ and improve support such as ‘language training’ for immigrant students ( Field et al., 2007: 150–1; OECD, 2008: 2). Challenge the disproportionate streaming of ‘minority groups’ into special education (2007: 20).

-

3.

Reform school practices. Make evidence-informed choices to address equity and ‘avoid system level policies conducive to school and student failure’ ( OECD, 2012: 10).

For example, first, repeating a school year is ineffective and exacerbates inequalities ( Field et al., 2007: 16–18; OECD, 2008: 4–5). Second, early tracking and selection (assigning students to different classes based on actual or expected attainment) exacerbates inequalities without improving overall performance (2008: 4; 2012: 11). Poor selection practices reduce the quality of education and ‘peer-group’ effects, increase stigma, and are based on unreliable indicators of future potential ( Field et al., 2007: 59). Third, parental choice on where to send their children can exacerbate inequalities related to demand (e.g., some have more resources to gather information and to pay for transport) and supply (e.g., the discriminatory rules for entry) (2008: 3; Field et al., 2007: 15; 62–4; see also Heilbronn, 2016).

-

4.

Seek effective school governance to ‘ help disadvantaged schools and students improve’ ( OECD, 2012: 11). Develop capacity in school leadership, provide ‘adequate financial and career incentives to attract and retain high quality teachers in disadvantaged schools’ (2012: 12), reject the idea that ‘disadvantaged schools and students’ should have lower expectations for attainment (2012: 12), and take more care to foster links with parents and communities to address unequal parental participation (2012: 12). ( Field et al., 2007: 19; OECD, 2012: 11–12; OECD, 2008: 5).

-

5.

Avoid the inequitable consequences of performance management and league tables. Measurement and targets can be useful to identify (a) unequal early-dropout rates and rates of attainment at school leaving age, and (b) school performance in reducing inequalities ( OECD, 2008: 7). However, the publication of crude league tables of schools exacerbates uninformed debate (2008: 7; Field et al., 2007: 131).

The overall international context for our review of education equity policy

While UNESCO is not absent from our review, the majority of articles identified in this review are country studies that engage with reference points associated with the World Bank (neoliberal policy and policymaking) and OECD (performance management). Governments tend to describe reforms to improve equity via (a) access to higher quality schooling and (b) reaching a minimum attainment threshold on leaving school. They respond to the pressures associated with international league tables that compare performance by country and compare school performance within each country (using measures such as PISA, Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) – Grek, 2009: 27; Schuelka, 2013).

Consequently, equity policies focusing on social determinants, social justice, and inclusion, struggle to compete. They are overshadowed by more politically salient debates on the relationship between economic growth/ competitiveness and education, including the idea that we can quantify the relative performance of each country’s education system and use the data to improve each system ( Grek, 2009: 27; Rizvi & Lingard, 2010: 133–6). Almost all of these policies shelter under the umbrella term ‘equity’.

Policy ambiguity: the competition to define and deliver equity

The included articles discuss a wide range of equity-related issues, in relation to: mixed-sex schools ( Zufiaurre et al., 2010), the proportion of girls in education or work ( Ham et al., 2011; Yazan, 2014), the representativeness of school leaders or parental involvement in relation to ‘race, gender, ethnicity, and social class’ ( Bertrand et al., 2018; Marshall & McCarthy, 2002: 498; Porras, 2019), language training for immigrant populations ( Brezicha & Hopkins, 2016: 367; Hara, 2017), the inclusion of the ‘Roma minority in Europe’ ( Alexiadou, 2019: 422), the fairness of teacher grading ( Novak & Carlbaum, 2017), school behavioural and expulsion measures ( Welsh & Little, 2018), access to health and physical education ( Penney, 2017), challenges to sex discrimination ( Meyer et al., 2018) or heteronormative schooling ( Leonardi, 2017), and encouraging equal access to vocational, further and higher education in relation to race, gender, socio-economic status or spatial justice, such as by developing regional college provision ( Gill & Tranter, 2014: 279; Pinheiro et al., 2016) or encouraging ‘student voice’ ( Angus et al., 2013). They describe initiatives that focus narrowly on school access and teaching ‘quality’ ( DeBray et al., 2014; Donaldson et al., 2016; Hanna & Gimbert, 2011; Louis et al., 2008), human rights to preschool education ( Mtahabwa, 2010), or the distribution of scarce resources ( De Lisle, 2012; Spreen & Vally, 2010).

However, most articles contribute to two themes. The first is the distinction between equity as ‘horizontal’ (treat equally-resourced people equally) or ‘vertical’ (treat unequally-resourced people unequally) in relation to access to opportunities, processes, or outcomes ( Gilead, 2019: 439; Rodriguez, 2004). Policy actors identify how reasonable it is for the state to intervene directly, or foster individual motivation backed by market driven measures to drive up school quality. Gilead (2019: 439) compares three common ways to describe equitable resource allocation, noting that the first two seem inadequate while the third receives inadequate support:

-

1.

‘Merit’. A sole focus on individual effort produces ‘severe inequalities and a neglect of the weakest members of society’.

-

2.

Thresholds. A focus on ‘improving the conditions of the least advantaged members of society’ such as via an attainment threshold, is feasible but allows ‘the stronger members of society to preserve their relative advantages’.

-

3.

Justice. Options to ‘equate justice with equality’ include equal (a) receipt of resources (such as to reduce geographical inequalities), (b) opportunities to education (although the meaning of ‘opportunity’ is contested), and (c) outcomes (embraced rarely because ‘it advances an unrealistic and potentially socially harming ideal’).

Second, they link these contested definitions of equity to governance, prompting most researchers to ask: (1) whose definition of equity matters, (2) what ways to achieve equity do they prefer, and (3) who should be responsible for equitable opportunities and outcomes? Most articles situate these discussions in relation to dominant, narrow definitions of school-driven equity, generally to highlight their limitations. They describe policymakers using the word ‘equity’ without establishing a clear mechanism to secure it, in a multi-level policymaking system over which they have limited control.

For example, many central governments pursue equal access to schools: favouring distribution and regulation (funding and regulating schools) over redistribution (taxing high income to compensate low income populations), and holding schools responsible for variations in outcomes despite social inequalities that are not amendable to change by education sectors alone. Further, central governments do not define equity policy well, increasing the possibility that local actors (including district and school leaders) can change policy as they deliver. The overall result is often a tension between multiple definitions of equity pursued in multiple levels of government.

In that context, we relate the included studies to two main categories:

-

1.

Critiques of dominant definitions in international and domestic agendas. This section describes the US as an exemplar of a problematic neoliberal model of equity policy, with most other countries presenting variations on the same theme.

-

2.

Competing definitions and alternative aspirations, focusing on a well-regarded model (Finland), and the standards or values that researchers use to analyse real-world practices.

1. Critiques of dominant definitions in international and domestic agendas

The US: ill-defined and contested equity. US studies treat equity as an often used but ill-defined and contested term. Ambiguity makes it difficult to clarify the implications for policy, and the intentional or unintentional lack of clarity exacerbates inequalities ( Bulkley, 2013; Chu, 2019). Contestation relates to horizontal versus vertical definitions:

‘Horizontal equity is concerned with providing equal treatment and provisions to all schools and students whereas vertical equity is concerned with ensuring that students with greatest needs or in disadvantaged conditions will receive more resources … The horizontal perspective of equity is similar to … a “thin” equity that prioritizes individuals’ equal access to educational resources and opportunities. In contrast, a “strong” equity recognizes the historical, socioeconomic, and racial inequities in education and calls for a structural, transformative approach to stop and uproot inequity’ ( Chu, 2019: 5, citing Cochran-Smith et al., 2017; see also Halverson & Plecki, 2015)

This distinction helps identify a spectrum of support for government intervention: ensuring procedural fairness in schools while assuming a meritocracy; redressing inequalities to encourage fairer competition; and, redistributing educational resources to ensure that no one dips below a performance threshold ( Bulkley, 2013: 11; Kornhaber et al., 2014). Bulkley’s (2013: 10) interviews of education researchers, advocates, and practitioners highlight disagreement on:

How to distribute inputs: such as an equal ‘opportunity to learn’ in a classroom. Most seek more resources – including ‘high quality’ teachers - for students in (a) high poverty areas (b) attending schools with lower resources (teaching and technology), and (c) likely to interact with teachers with less experience and more turnover (2013: 15–16). One exception was the American Enterprise Institute which argues that redistribution would reduce overall quality and performance and disadvantage better performing middle class schools (2013: 16; 20).

How to set boundaries between education and other policy domains: How to define ‘low income’ and set boundaries between public education and other policies with a major influence on learning (e.g., on health, nutrition, housing) (2013: 11). Some call for more recognition of the wider context; others think it lets schools off the hook for their performance (2013: 16).

Who should be responsible, and what they should they do: Debates focus on reforming existing services or introducing more market mechanisms (2013: 17). They focus on course content, classroom practices, segregation by socioeconomic status, the governance of schools, the allocation of teacher time, and incentives such as school vouchers (2013: 12).

How to set expectations for equity of outcomes: Debates on the appropriate outcomes in relation to attainment - ‘equity as equal outcomes, equity as meeting a threshold, and equity as making progress’ - include a threshold to allow social, economic, and political participation, plus a judgement on how much equalization of achievement is possible or desirable ( Bulkley, 2013: 12; 18). Outcomes can refer to reducing gaps in attainment or the link between attainment and employment. Thresholds include graduating high school or being college-ready.

One way to address this ambiguity is to exercise power – via professional discourse and political processes - to resolve contestation in favour of one definition. However, Chu (2019: 3) finds that state governments define equity vaguely. There is some government action to set expectations, but many are clarified in practice. This lack of care to define a social justice-oriented agenda minimises the challenge to individualist notions of education built on neoliberalism, market mechanisms, and performance management ( Bishop & Noguera, 2019; Evans, 2009; Hemmer et al., 2013; Horn, 2018; Lenhoff, 2020; Trujillo, 2012; Turner & Spain, 2020).

Australia: equal access to schooling in an unequal socioeconomic and spatial context. Australian studies critique a tendency to connect (a) giving ‘everyone a chance at the same outcomes’ regardless of wealth or culture, to (b) access to schooling, rather than (c) the social determinants of unequal outcomes ( Loughland & Thompson, 2015; Taylor, 2004: 440). The wider context is a highly stratified society exacerbated by private versus public education: disadvantaged students go to state schools while others go to the better funded and performing private sector, with fee-paying schools also subsidised by the federal government ( Loughland & Sriprakash, 2016: 238; Morsy et al., 2014: 446). The education system is designed to encourage unequal outcomes via competition and performance management. Loughland & Sriprakash (2016: 238) describe a PISA-driven agenda which contributes to ‘a performative framework for equity’ conflating ‘quality and equity’ (2016: 238).

In other words, policymakers pretend that the highest quality education is available to all ( Clarke, 2012: 184). Federal government descriptions of a ‘sector-blind’ policy, funding all schools, avoids discussing redistribution to address disparities in social background and achievement, linking education to individual success and economic competitiveness rather than collective wellbeing ( Taylor, 2004). Morsy et al. (2014: 446) describe a strategy to depoliticise education equity to maintain inequalities of power and outcomes: (1) emphasising governmental neutrality, the technical aspects of policy, and the value of market mechanisms; (2) prioritising individual effort and success; and (3) describing the welfare state as political and markets as natural. Overall, equity is about competition and performance, not social inclusion (2016: 239–40). This approach exemplifies an international tendency to use performance measures and league tables to describe education inequalities as natural, fostering the ‘stigma of failure at institutional and individual levels’ that exacerbates wider social inequalities ( Power & Frandji, 2010: 394, describing England and France).

In that context, we can only make sense of the overall impact of equity agendas by relating them to the more-supported policies that exacerbate inequalities in practice. In particular, Reid (2017) shows how the neglect of spatial injustice exacerbates the racial and ethnic inequalities that Australian governments allegedly seek to reduce: there is lack of access to high quality schooling in rural areas, which have relatively high Indigenous populations. There has been a “national emphasis since 2007 on ‘closing the gap’ in education, health and economic outcomes for Indigenous Australians”, with ‘education policy aimed at raising educational attainment by improving early education programs, preschool attendance, improving primary schooling, and providing financial incentives to attract experienced and successful teachers to the most disadvantaged schools’ (2017: 89). However, the wider policy context worsens ‘the effects of dominant sociological issues of race, class, gender and geography’ (2017: 89; Molla & Gale, 2019).

Gill & Tranter (2014: 291) suggest that policymaker and media agendas exacerbate such problems by drawing incorrect conclusions from data. They describe the perception – derived wrongly from the rise of middle-class women going to university – that girls are more likely than boys to overcome class-based disadvantage. There is a long-term government and media concern about working class boys being marginalised in education - the ‘new’ disadvantaged in relation to ‘retention rates, expulsion and suspension rates, lower levels of literacy and social and cultural outcomes’ – without considering (say) their greater ability to receive the same employment opportunities with fewer qualifications ( Gill, 2005: 108–110; compare with Martino & Rezai-Rashti, 2013 on Canada). In contrast, gender equity movements focus on the unspoken sources of inequity in relation to gendered roles in public and private, expectations in education and employment, and gendered violence ( Marshall, 2000).

Canada: unequal outcomes masked by the rhetoric of equitable policies. Studies of federal and provincial policies in Canada highlight the lack of practical meaning of ‘equity policy’ rhetoric. Canada exemplifies a contrast between (1) practices that exacerbate inequalities and (2) the vague rhetoric of equity that masks their effects. Practices include fiscal inequalities, where unequal funding for schools from private funds relates inversely to socioeconomic need ( Winton, 2018); some districts are relatively able to raise revenue in the market and use it to improve schools in that district (2009: 160). A government commitment to equity of achievement – in relation to class, race, and gender – remains unconnected to finance and geography.

Further, equity policies related to anti-racism and multiculturalism are diluted by other agendas. George et al. (2020: 172–3) identify in British Columbia and Ontario a tendency for policy documents to describe individual rather than structural determinants of racism. Paquette (2001) describes failed bids in British Columbia to produce policies that reduce inequalities in relation to race, ethnicity, gender, and/or disability, in a context of (a) constrained government spending and (b) a commitment to standardised testing to gauge individual and school performance. Segeren & Kutsyuruba (2012: 2) describe ‘a noticeable retrenchment with respect to equity policies’ in the Ontario Ministry of Education, with equity subsumed ‘under the banner of school safety, discipline, harassment, and bullying’.

Authorities foster symbolic measures to look like they are addressing education inequity (in relation to a threshold of attainment) ( Hamlin & Davies, 2016). For example, Toronto’s global multicultural image helps mask important variations of experience (2016: 189). Further, Gulson & Webb (2013: 173) connect the ‘underachieving’ of black students in a Toronto district with thwarted attempts to respond, such as proposals for a black-focused curriculum or to set up Afrocentric schools. The governance mechanisms exist to support this proposal, but it has faced intense local opposition (2013: 171).

There is also a tendency towards rhetoric to address the transition to HE that exacerbates inequalities in education ‘on the basis of ethnicity, ability/disability, gender, sexuality, and religion’ ( Tamtik & Guenter, 2019: 41). There is a suite of potential approaches to inequalities, including: to foster inclusion, the value of difference, recognition, and a removal of barriers to education such as discrimination against students and cultural isolation; and, hiring and promoting staff from a wider pool (2019: 43). However, most universities focus on minimum standards of attainment, while few relate fairness to redistributing resources.

Country studies: a general contrast between equality of access versus outcomes. Multiple country studies provide a similar contrast between dominant versus their preferred approaches. They highlight a tendency to foster equality of access to education (often backed by market mechanisms such as voucher and school choice schemes) and measure outcomes narrowly, at the expense of a meaningful redistribution of resources or alternative measure of success:

In Cyprus, a focus on access to schools, combined with limited school action, fails to address ‘the actual experience of marginalisation, disadvantage or discrimination’ and ‘points to cultural domination, non-recognition and disrespect’ ( Hajisoteriou & Angelides, 2014: 159).

In Denmark, Engsig & Johnstone (2015: 472) identify the contradictions of educational ‘inclusion’ policies with two different aims: (1) social inclusion and student experience (the UNESCO model, adapting to students), and (2) mainstreaming in public education coupled with an increased focus on excellence and quality, via high stakes student testing to meet targets (the US model, requiring students to adapt).

In Sweden and Norway, Pettersson et al. (2017: 724) describe the strategies favouring a neoliberal focus on equal access. In Sweden, it contributed to school choice agendas that increased segregation ( Varjo et al., 2018: 482–3). A comparison with Finland suggests that such measures can still be highly regulated by government (2018: 489–92).

In Chile, advocates for markets argue that they increase access, for disadvantaged students, to high quality schools ( Zancajo, 2019). However, empirical evidence highlights the opposite. Socioeconomic status influences the ability and willingness to exploit school choice, while private school selection practices maintain segregation (2019: 3).

Verger et al.’s (2020) review of public private partnerships (PPP) suggests that Chile’s results are generalisable: ‘PPPs generate a trade-off among social equity and academic achievement. Thus, if the aim of educational policy is to promote inclusion and equity, the implementation of most of the PPP programmes analysed in this paper would not be advisable’ (2020: 298).

2. Competing definitions and alternative researcher aspirations

Eng (2016: 676–7) highlights the major disconnect between: (1) research showing that social determinants are more important to attainment than school performance; and, (2) the US public and policymaker tendency to see this issue in terms of individual merit and school or teacher performance. Eng’s (2016: 683–6) recommendation is to emphasise the benefits of a ‘systems approach’ and ‘collective action’ to counter ‘individualistic thinking’.

More generally, research recommendations include to: avoid narrow definitions of equity associated with school performance and testing; foster more inclusive and deliberative dialogue between school leaders, teachers, and communities to co-produce meanings of equity; recognise how multiple forms of inequality and marginalisation reinforce each other; ‘treat race as an urgent marginalising factor’ and gather specific data to measure racialised outcomes ( George et al., 2020) rather than hiding behind ‘colour blind’ or ‘race neutral’ strategies ( Felix & Trinidad, 2020; Li, 2019; McDermott et al., 2014); and, provide proper resources to address sex discrimination ( Meyer et al., 2018).

In that context, Thorius & Maxcy (2015: 118) describe ‘six transformational goals’ for ‘equity-minded policy’: ‘(a) equitable development and distribution of resources, (b) shared governance and decision making, (c) robust infrastructure (e.g., efficient use of space and time), (d) strong relationships with families and community members, (e) cultures of continuous improvement, and (f) explicit emphases on equity’. Multiple studies use such goals to set standards for policy reforms.

Finland’s comprehensive model. Finland has an international reputation for pursuing equity via lifelong learning and a comprehensive schooling system, supported by a Nordic welfare state ( Grek, 2009: 28; 33; Lingard, 2010: 139–40; Niemi & Isopahkala-Bouret, 2015). Equity means ‘minimising the influence of social class, gender, or ethnicity on educational outcomes’ while making sure that everyone achieves a threshold of basic education and skills via:

-

1.

‘active social investment through universal early childhood education’

-

2.

‘a comprehensive education model’ in which every school has a near-identical standard

-

3.

‘the provision of support to lower-performing or at-risk students’

-

4.

resistance to neoliberal, market-based reforms that foster individualism and competition ( Chong, 2018: 502–5).

Consequently, it has enjoyed high praise from: the OECD for minimising the number of people leaving school without adequate skills ( Field et al., 2007: 26), and researchers who welcome a focus on social determinants (although the focus on a threshold contrasts with HiAP - Cairney et al., 2021).

Equity-oriented leadership: education debts and recognition. Farley et al. (2019: 2) examine how ‘leadership standards … represent evolving conceptions of equity and justice’. The context is a drive in the US for schools led by ‘equity-oriented change agents’ (2019: 4). It is undermined by a tendency for equity and justice to be defined in different ways in professional standards and training, with too few connections to social justice research and too many individualist conceptions of achievement gaps (2019: 9). Problems of inequity are ‘wicked’ and ‘relentless’, and not amenable to simplistic solutions based on ‘equal access to resources, curriculum, or opportunities’ (2019: 15). Rather, Farley et al. (2019: 9) laud Ladson-Billings’ (2008); Ladson-Billings’ (2013) idea of an ‘education debt’ in which all members of society should consider their contribution to inequalities and challenge the sense that the ‘attainment gap’ is inevitable (see also Horn, 2018: 387). They seek recognition approaches that ‘characterize injustice as both structural and as an inherent failure of society to recognize and respect social groups’, including ‘the way that individual actors can oppress groups via exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence’ ( Farley et al., 2019: 10):

‘These educators foreground their commitment to social justice and equity and avoid deficit views - and they also reflect those values in their practice. They take part in courageous and vulnerable conversations, persist in working to remove inequities, and respect and appreciate the assets within their students and their communities’ (2019: 3).

Similarly, Feldman & Winchester (2015: 69–71) distinguish between (a) the limited-impact formal measures that establish legal rights, and (b) policy designs grounded in practice and continuous discussion - ‘courageous conversations’- over many years. Crucially, policy does not have a settled definition. Equity is to be negotiated in practice as part of an inclusive approach to policymaking, backed by the commitment of school districts to ‘owning past inequity, including highlighting inequities in system and culture’ and ‘foregrounding equity, including increasing availability and transparency of data’ ( Rorrer et al., 2008: 328).

Challenge the ‘colour evasiveness’ of ‘equity for all’ initiatives. Felix & Fernandez Castro (2018: 1) examine the Student Equity Plans that Californian community colleges are obliged to produce, to identify how they operationalise equity. This focus is significant since there is highly unequal access to elite universities in favour of white populations ( Baker, 2019), and public and private research universities spend double per student than community colleges ( Felix & Fernandez Castro, 2018: 3). The latter ‘enrol a larger proportion of low-income, first-generation, and racially minoritized students [70% of students of colour]… a disproportionate number of students who have faced constant disadvantage and inequality throughout their educational trajectory’ (2018: 3), and their dropout rates are far higher (2018: 3–4).

In that context, are colleges race-conscious, and do they hold practitioners and institutions - rather than students - responsible for the pursuit of equitable outcomes? Few (28/178) plans ‘explicitly targeted Black and Latinx students with culturally relevant, data-driven, evidence-based strategies’, partly because funding incentives for equity plans only appeared in 2014 (2018: 2) and because California rejected (via general election ballot) ‘affirmative action’ policies ( Baker, 2019; Felix & Trinidad, 2020: 466). Instead, there is a tendency to produce ‘equity for all’ messages to address disadvantaged groups related to ‘race/ethnicity, gender, veteran status, foster youth, socioeconomic status, and ability status’ ( Felix & Fernandez Castro, 2018: 7–9; 24). This outcome relates strongly to ‘interest convergence’: when white people only agree to policies benefiting racialised minorities if they too benefit ( Felix & Trinidad, 2020: 470). Or, schemes have a faulty logic, such as the ill-fated financial incentive to complete 100 hours of community work ($4,000 towards college tuition) which supports the relatively affluent students who can afford to work without pay ( Wells & Lynch, 2014)

Similarly, McDermott et al. (2014: 541) use US case studies of ‘student assignment policy’ to show that ‘race-neutral policies seem to generate the opposite dynamic’. The context is of historic problems with desegregation policies designed to address the unequal quality of schools available to white and black students. They prompted a trend towards ‘race-neutral politics’, focusing on addressing socio-economic issues rather than race, to make policy changes less vulnerable to legal and political challenge by the white majority. Policy helps to reduce overt bigotry but also hide and exacerbate racialised disparities because: (a) a focus on less-advantaged and needier students allows white parents to oppose their inclusion without referring to race, (b) people can oppose ‘busing’ children to school with reference to cost, and (c) people seeking ‘enclave’ schools can refer to the common sense of neighbourhood schools rather than keeping out black children (2015: 541–3).

Foster a ‘capabilities’ approach. Multiple studies highlight measures taken in the name of equity which fail to reduce inequalities. In New Zealand, removing HE fees without addressing inequalities of debt or ability to attend, while providing superficial support to tailor schooling to Maori culture, produces the veneer of equity but unequal outcomes ( Barker & Wood, 2019). In many sub-Saharan African states, unequal access to high quality HE is exacerbated by multiple and intersecting sources of disadvantage and marginalisation, despite the pursuit of equity initiatives by UNESCO, the World Bank, the African Union, the African Development Bank, and the Association of African Universities ( Singh, 2011).

Some studies draw on Sen (1999); Sen (2009) and Nussbaum (2000) to highlight a ‘capabilities approach’. It fosters a learning environment more tailored to people’s needs and more able to empower them to learn ( Wahlström, 2014). It incorporates the unequal ability of people to take up opportunities to learn when they are subject to differences in power, culture, and resources.

Molla & Gale (2015: 383) apply this approach to HE ‘revitalization’ in Ethopia, driven by ‘social equity goals’ and ‘knowledge-driven poverty reduction’ (encouraged by the World Bank). They found that equity policies included a commitment to address previous ethnic injustices, targets and resources to enable disadvantaged groups to enrol, lower entry requirements for disadvantaged groups, and expansion from 2 to 32 universities and from 20k to 250k students by 2012 (using the private sector to fund expansion) (2015: 385–6). Yet, ‘the problem of inequality has persisted along the lines of ethnicity, gender, rurality and socio-economic background’ (2015: 383). For example, women represent 26.6% of enrolled undergraduate (20% postgraduate taught, 17% PhD), concentrated in non-STEM subjects, and with higher attrition rates linked strongly to sexual harassment and assault by male teachers and students (2015: 388; compare with Wadesango et al., 2011 on schools in South Africa). There are also geographical variations in school completion/HE eligibility, and ‘over 70% of students in Ethiopian HE come from families in the top income quartile and from urban areas’ (2015: 387).

Molla & Gale (2015: 383) identify the lack of attention to ‘a deprivation of opportunities and freedom’. A focus on capabilities emphasises the role of education in wellbeing and freedom: the ability to read, write, think, and deliberate contributes to self and external respect and access to further opportunities. It highlights the barriers to that freedom, including ‘structural constraints (embedded in policies, curricula, pedagogical arrangements, social relations and institutional practices) that limit agency freedom and deny social groups recognition and respect’ ( Molla & Gale, 2015: 389–90). Progress requires agency to ‘convert’ resources and opportunities into processes and outcomes: ‘repressive cultural values of society and public policy inactions influence people’s subjective preferences and constrain their real opportunities to choose, and thereby create and sustain inequality’ (2015: 390). This is about the fairness of allocation and the relevance of opportunities to each person or group, subject to their levels of repression, poverty, and geography.

Policymaking contradictions: neoliberalism versus social justice. Hajisoteriou & Angelides (2020) describe competing definitions of education equity as neoliberal versus social justice, which interact to produce often-contradictory approaches. They describe global policymaking as two-headed: ‘beyond the rise of hyber-liberalism, xenophobia and socio-economic inequity, globalisation has also humanistic and democratic elements” (2020: 282). Globalisation has helped produce ‘global policies of social justice and equity’ as well as increased migration, and ‘may play a substantial role in the development of minority and immigrant rights, while also moving citizenship debates beyond the idea of the nation state’ (2020: 278; 282). There is also a dominant discourse on human capital and global economic competitiveness, combined with NPM techniques:

‘international benchmarking, the privatisation of education, importing management techniques from the corporate sector and other ideals such as choice, competition and decentralisation … school-based management, teachers’ accountability, public-private partnerships and conditional fund-transfer schemes are some of the global education policies often cited as a result of neoliberalism’ (2020: 277).

This dominance has a profound impact on professional practice, at the expense of social justice:

“global discourses of social justice and equity of educational opportunity appear to be often counteracted by global discourses of neoliberalism, which are embedded in international performance indicators, and international tests and scores. Market oriented education seems to overrule policy reforms aiming to achieve equity in education …[producing] educational policies preoccupied with efficiency, ‘excellence’, ‘standards’ and ‘accountability’" (2020: 282; 277).

It extends to the classroom, pressuring teachers “to become classroom ‘technicians’ whose quality is defined in terms of testable content knowledge instead of professional knowledge”, limiting their ability to promote a social justice approach to education as ‘critical thinkers, active professionals and thus agents of change’ (2020: 283; Klees & Qargha, 2014: 323).

Variable country and regional experiences of neoliberal policies. Many country and regional studies make the similar argument that ‘central neoliberal technologies of accountability, competition, privatization, marketization, managerialism, and performativity’ undermine equity initiatives ( Clarke, 2012: 176). However, the effect is not uniform ( Novak & Carlbaum, 2017: 673). There is a spectrum of cases in which neoliberal ideas are dominant or resisted.

For example, neoliberalism is the established order in the US, and studies suggest that a market-driven narrative undermines a social determinants focus ( Chu, 2019). Further, studies of Australia and New Zealand present a similar assumption that neoliberal approaches have long dominated education policies. Clarke (2012: 172) describes a tendency for Australian governments to embrace neoliberal approaches to globalisation, emphasising individualism and markets, and situating education policy and the measurement of a country’s educational performance in that context (2012: 175). A focus on education for the economy dominates, with social justice programmes treated as bolt-ons and band-aids (2012: 176; see also Angus et al., 2013: 563; Loughland & Sriprakash, 2016: 230; Morsy et al., 2014; Taylor, 2004: 439–40). Worryingly low trust in, and respect for, teachers reflects New Zealand’s contradictory ‘neoliberal education policy which has pushed for simultaneous devolution and control, marketisation and competition for more than 30 years’ ( Barker & Wood, 2019: 239).

Canadian experiences are somewhat different, since Mindzak (2015: 112) relates the lack of US-style charter schools (run by private boards) to a ‘commitment to equity’ built on ‘an overarching belief in the moral rightness of public systems of education in Canada’, a tendency for more equitable funding for schools (across and within provinces), and a wider commitment to the welfare state. Further, ‘Toronto has rejected many exported reforms from the United States, such as high-stakes standardized examinations, school sanctions for low performance, value-added evaluations of teachers, and charter school and voucher programmes’ ( Hamlin & Davies, 2016: 190). Regional and country studies describe the threat of neoliberalism to a more communitarian history, and the inherent contradictions in Canadian policy rhetoric. Most identify the alleged-but-unfulfilled expectation that market-led initiatives (vouchers and school choice) would reduce education inequalities, some highlight their contribution to the neglect of anti-racist policies, and some describe multiculturalism as a tool of economic policy (e.g., Fallon & Paquette, 2009; Gulson & Webb, 2013; Martino & Rezai-Rashti, 2013; Paquette, 2001; Segeren & Kutsyuruba, 2012; Winton, 2018).