Abstract

As one of the most morphologically conservative branches of the Sino-Tibetan language family, most of the Rgyalrongic languages are still understudied and poorly understood, not to mention their vulnerable or endangered status. It is therefore important for available data of these languages to be made accessible. The present lexical data sets provide comparative word lists of 20 modern and medieval Rgyalrongic languages, consisting of word lists from fieldwork carried out by the first author and other colleagues as well as published word lists by other authors. In particular, data of the two Khroskyabs varieties are collected by the first author from 2011 to 2016. Cognate identification is based on the authors' expertise in Rgyalrong historical linguistics through the neogrammarian comparative method. We curated the data by conducting phonemic segmantation and partial cognate annotation. The data sets can be used by historical linguists interested in the etymology and the phylogeny of the languages in question, and they can use them to answer questions regarding individual word histories or the subgrouping of languages in this important branch of Sino-Tibetan.

Keywords: lexical data; historical linguistics; language phylogeny; Rgyalrongic; Sino-Tibetan; language subgrouping; partial cognate annotation; endangered languages

Plain language summary

Rgyalrongic languages are mainly spoken in Western Sichuan, China, albeit including a now extinct, medieval language, namely Tangut, attested in today’s Ningxia Province. For most non-native speakers, they are the most difficult branch of languages to learn in the Sino-Tibetan family, as they exhibit a large array of word formation strategies such as inflection and derivation. Their word complexity points to their old age and their value in finding out the origin of Sino-Tibetan. This database aims at gathering lexical information of Rgyalrongic languages, in preparation for future work on historical and evolutionary linguistics.

Introduction

Rgyalrongic languages are a Sino-Tibetan branch, mainly spoken in Rngaba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan, China 1, 2 . They are closely related to Lolo-Burmese languages 3 . Apart from their modern varieties, which are mostly endangered or vulnerable, a medieval language, Tangut, is recently recognised to belong to said branch 4 . Rgyalrongic languages are traditionally divided in two sub-branches, the east sub-branch and the west sub-branch. East Rgyalrongic is comprised of four main languages, Situ, Zbu, Japhug and Tshobdun, and West Rgyalrongic of three further sub-branches, Khroskyabs, Stau (aka. Daofu) and Tangut. Recent phylogenetic studies, however, show that Zhaba is also clustered in Rgyalrongic 3 . Thus, it is very likely that language varieties closely linked to Zhaba, such as Queyu and Minyag (aka. Muya, Menya) and Zlarong spoken in the Tibetan Autonmous Region, are also Rgyalrongic languages. These “newcomers” are provisionally termed “Peripheral Rgyalrongic” in the following.

Rgyalrongic is one of the most morphologically conservative branches in the Sino-Tibetan family, and certainly the closest to Proto-Sino-Tibetan compared to all other varieties in China. Therefore, understanding the history of Rgyalrongic languages is vital for the study on the evolution of Sino-Tibetan. The phylogeny of Rgyalrongic with dating information is thus an essential step towards this goal. Lexical data is the most accessible means to approach language phylogeny and has been proven to show accurate results 3, 5 . In order to infer the phylogenetic subgrouping of Rgyalrongic, a lexical dataset with high quality curation is inevitable. This database provides the first annotated resource for the phylogenetic analyses of Rgyalrongic languages. It includes twenty varieties in East, West and Peripheral Rgyalrongic, as shown in the map in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of the languages in the database.

Table 1. Languages selected for the database.

| Languages ID | Language name | Glottolog | Longitude | Latitude | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bantawa | Kiranti Bantawa | bant1281 | 87.05 | 27.12 | Doornebal (2009) 6 |

| Daofu | rGyalrong Daofu | horp1240 | 101.12 | 30.98 | Huang (1992) 7 |

| Japhug | rGyalrong Japhug | japh1234 | 101.96 | 32.21 | Jacques (2015) 8 |

| Tangut | Tangut | tan1334 | 106.29 | 38.48 | Li (1997) 9 |

| WobziKhroskyabs | Khroskyabs Wobzi | eree1240 | 101.43 | 31.63 | Lai (2017) 10 |

| Zhaba | Qiangic Zhaba | zhab1238 | 101.06 | 30.54 | Huang (1992) 7 |

| MaerkangrGyalrong | rGyalrong Maerkang | situ1238 | 102.30 | 31.87 | Huang (1992) 7 |

| MuyaKangding | Muya-kangding | west2417 | 101.96 | 30.06 | Huang (1992) 7 |

| MenyaGao | Menya-Gao | west2417 | 101.53 | 29.80 | Gao (2015) 11 |

| OldBurmese | OldBurmese | oldb1235 | 96.60 | 21.46 | Dictionary |

| QueyuXinlong | Queyu Xinlong | quey1238 | 100.26 | 30.98 | Huang (1992) 7 |

| QueyuPubarong | Queyu Pubarong | quey1238 | 100.78 | 30.22 | Guan Xuan’s fieldwork |

| SiyuewuKhroskyabs | Siyuewu Khroskyabs | siya1242 | 101.42 | 31.75 | Author’s fieldwork |

| BragbarSitu | Bragbar Situ | situ1238 | 101.91 | 31.82 | Zhang (2020) 12 |

| Geshiza | Geshiza | horp1240 | 101.65 | 31.03 | Honkasalo (2019) 13 |

| GuanyinqiaoKhroskyabs | Guanyinqiao Khroskyabs | guan1252 | 101.66 | 31.78 | Huang (2007) 14 |

| NjorogsKhroskyabs | Njorogs Khroskyabs | yelo1242 | 101.86 | 31.82 | Yin (2007) 15 |

| Tshobdun | Tshobdun | tsho1240 | 101.83 | 32.21 | Sun (2019) 16 |

| NgyaltsuZbu | Ngyaltsu Zbu | zbua1234 | 101.74 | 32.15 | Gong (2018) 17 |

| Zlarong | Zlarong | zlar1234 | 98.09 | 29.93 | Zhao (2019) 18 |

| KyomkyoSitu | Kymokyo Situ | situ1238 | 102.04 | 31.99 | Prins (2017) 19 |

| MazurStau | MazurStau | daof1238 | 101.05 | 31.04 | Gates (2021) 20 |

Methods

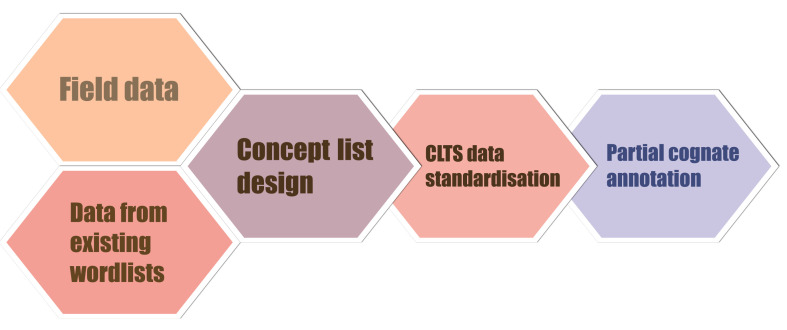

The entire workflow to build our database is illustrated in Figure 2. We started with the collection of raw data, collected from original fieldwork and from existing word lists. We then organised our raw data into a specifically designed and curated word list. In the third step, we conducted data standardisation conforming to standards outlined by the Cross-Linguistic Data Formats Initiative. Finally, we identified and annotated cognate sets for individual morphemes, also known as partial cognates 21 .

Figure 2. Workflow of building up the Rgyalrongic lexical database.

Major sources of the dataset

The major sources of the dataset include original fieldwork from one of the authors of this study (YFL) and various colleagues who generously shared their lexical data, ie. word lists. The author’s original field data involves two varieties of Khroskyabs, Siyuewu and Wobzi. All the vocabulary needed for this dataset has already been collected before 2017, prior to any of the research projects acknowledged in this paper. Fieldwork involved verbal exchanges with native speakers, requesting pronunciations of words and expressions, without physical contact. An additional source of data was published dictionaries and word lists which were judged as reliable by the authors (see Table 1). Dictionaries and word lists typically contain word forms and translations in Chinese, French or English. Some word lists also provide morphological information and example sentences. Reliability is assessed through two aspects: i) internal phonological consistency of the source data. The authors check if phonemes are correctly identified and that allophones conditioned by phonological environments and morphological alternations are adequately represented in the original sources. ii) external regularity of sound correspondences with the comparative method. The authors checked if cognate forms in the sources exhibit regular correspondences or correspondences that can potentially be explained through alternations or analogy. Languages in our dataset are listed with their sources, their Glottocodes 22 and approximate coordinates in Table 1. There are several cases where two or three languages share the same Glottocode (for the general idea behind Glottocodes, see Forkel and Hammarström 23 ). Maerkang (MaerkangrGyalrong), Bragbar Situ (BragbarSitu) and Kyomkyo Situ (Kyomkyositu) share the glottocode “situ1238”, however, they are distinct varieties of Situ with limited intelligibility. The two dialects of Minyag sharing the glottocode “west2417”, labelled MuyaKangding and MenyaGao, are closely related dialects with minor differences. Queyuxinlong and QueyuPubarong (quey1238) are closely related dialects with significant differences in phonology and vocabulary.

Apart from Rgyalrongic languages, we have included two outgroup Sino-Tibetan languages for the accuracy of phylogenetic inference: Bantawa and Old Burmese. The outgroup is used as a reference point to locate and root the ingroup (Rgyalrongic languages). Bantawa belongs to the Kiranti branch mainly spoken in Nepal. Old Burmese was an ancient Lolo-Burmese language attested between 12th and 16th century in present day Myanmar. These two languages are remotely related to Rgyalrongic. According to Sagart et al. 3 , Kiranti languages branched off from other Sino-Tibetan subgroups approximately 5500 years from present, and Lolo-Burmese separated from Rgyalrongic some 4300 years from present. These two languages are suitable for outgroups in the present study, as Bantawa is sufficiently remote to Rgyalrongic, and Old Burmese has a clear date of attestation and can be used for the calibration of dating.

Data presentation

An extended concept list based on the one used in Sagart et al. 3 is employed as a guideline of our word selection in each language, including 313 concepts linked to Concepticon 24 which provides a unique identifier to all concepts and thus largely facilitates language documentation and historical comparison of lexicon. The concept list used is specially designed for Sino-Tibetan languages, therefore it is most suitable as the starting point of the present dataset. According to our data quality and coverage, we made minor modifications to that concept list by adding and deleting some of the concepts. In particular, we added concepts having a wide coverage in Rgyalrongic languages which are however not widely distributed from the perspectives of the entire Sino-Tibetan family. For instance, we use the general concept for ‘person, human’ instead of ‘the man (male human)’ used in Sagart et al. 3 , which has been shown to be indicative of language subgrouping by Lai 25 ; we also included ‘girl’, as a significant innovation in West Gyalrongic with an s-prefix (compare Stau (West) s-mi and Japhug me (East)), discussed in Lai et al. [ 4, 177]. In addition, concepts such as ‘knife’, ‘work’ and ‘sit’ and so on also exhibit similar types of innovations across Rgyalrongic languages, we therefore consider them as worthwhile to be included in the dataset.

Data standardisation

After collecting the raw word list of each language, we conducted a standardisation process of the data, because the original phonetic transcriptions may differ from each other, some may not adhere strictly to the rules of the International Phonetic Alphabet. The revised transcriptions are based on the transcription conventions in Cross-Linguistic Data Formats reference catalog (CLTS, https://clts.clld.org, 21, 26– 28) and set up an orthography profile 29 that helped us automatically convert all transcriptions according to our standard. The standardised data aims specifically at the computation of language phylogeny.

Partial cognate annotation

Cognates are words or part of words in different languages that share the same origin, such as English foot and German fuß, both originating from Proto-Germanic *fōts. Cognate forms in daughter languages can be deducted through regular sound rules from the proto-form. In Sino-Tibetan languages, more often than not, we find cognates in word parts rather than in entire words. For instance, Mandarin Chinese yuè-liang ‘moon’ and Taiwanese Southern Min guēh-niû n ‘moon’ only share the first part yuè and guēh, respectively, as cognates. This type of cognacy is termed “partial cognacy”. Partial cognates enable us to segment word forms into morphemes, which improves the accuracy of the computation of language subgrouping. It is thus essential to annotate partial cognates, rather than full cognates, in our Rgyalrongic database. Partial cognate identification is conducted manually with the expert knowledge of the authors, using the web-based EDICTOR tool ( https://digling.org/edictor, 30, 31).

Statistics

The current dataset contains a total of 6335 word forms for 22 distinct language varieties. Word forms correspond to 305 different concepts, and use a total of 413 distinct sounds, with an average inventory size of 72 different sounds per language variety. The word forms have been morphologically segmented, comprising a total of 9116 morphemes. These morphemes have been assigned to 3109 cognate sets. Of these cognate sets, 1665 are unique, which means that we could not identify related words in other languages.

Quality control

We carefully verified the data to ensure the accuracy and correctness. We use our expert knowledge to review every lexical entry in the database. Whenever in doubt, we would contact the authors of the original sources for confirmation and correction.

Using an orthography profile, the transcriptions were converted according to a unified standard for potential reuses. Phonemic and morphemic segmentation, as well as cognate judgements are carefully processed with expert knowledge. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Partial cognate annotation: The concept ‘yesterday’ in Rgyalrongic is a compound of ‘past’ (cognates ID-7566 or ID-7567) and ‘day’ (cognates ID-7579 or ID-7615).

Languages differ in the choices of the two parts. Annotating the two parts separately allows us to visualise and analyse the internal morphology of the forms for more accurate inference of phylogeny.

Discussion and conclusion

Rgyalrongic languages are one of the most essential keys to the reconstruction of Proto-Sino-Tibetan as well as to the subgrouping of this language family. Although there exist searchable databases such as STEDT 32 ( https://stedt.berkeley.edu/) and the rGyalrongic Language Database 33 ( https://htq.minpaku.ac.jp/databases/rGyalrong/), the present database is the first Rgyalrongic lexical database that involves expert data curation and cognate annotation, and the only one that is ready for phylogenetic analyses.

For now, only those morphemes are assigned to the same cognate set which occur in words sharing the same meaning. In the future, we hope to extend this analysis to account for cognates across meaning slots, specifically concentrating also on language-internal partial cognates along the lines of the analysis pioneered in Hill and List 21 and further extended in Schweikhard and List 34 . Having annotated the data in this form, cognacy can also be annotated on the word level 35 and computational approaches to phylogenetic reconstruction of Rgyalrongic (and beyond) can be carried out. Thus, the present contribution may serve as the very base of future phylogeny of one of the most conservative sub-branches of Sino-Tibetan.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude goes to Gao Yang, Jesse Gates, Gong Xun, Guan Xuan, Sami Honkasalo, Guillaume Jacques, Zhang Shuya and Zhao Haoliang for their generosity of contribution of data and detailed explanations to our questions. We also thank Mei-Shin Wu for her help in refining the data.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the European Union under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (ERC Starting Grant CALC, grant agreement number 715618, DOI: \url{https://doi.org/10.3030/715618}, awarded to JML) and under the Horizon Europe research and innovation program (ERC Consolidator Grant ProduSemy, grant agreement number 101044282, DOI: \url{https://doi.org/10.3030/101044282}, awarded to JML), and by the Irish Research Council under the SFI-IRC Pathway Programme (Project id: 21/path-a/9374, Gyalrongic unveiled: Languages, Heritage, Ancestry, awarded to Yunfan Lai). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations]

Data and software availability

Data and Software available from: https://github.com/lexibank/lairgyalrong/.

Archived source code and data at time of publication: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7866796

License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0)

References

- 1. Sun JTS: Stem alternations in Puxi verb inflection: Toward validating the rGyalrongic subgroup in Qiangic. Lang Linguistics. 2000;1(2):211–232. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun JTS: Parallelisms in the verb morphology of Sidaba rGyalrong and Lavrung in rGyalrongic. Lang Linguistics. 2000;1(1):161–190. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sagart L, Jacques G, Lai Y, et al. : Dated language phylogenies shed light on the ancestry of Sino-Tibetan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(21):10317–10322. 10.1073/pnas.1817972116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lai Y, Gong X, Gates JP, et al. : Tangut as a West Rgyalrongic language. Folia Linguistica Historica. 2020;41(1):171–203. 10.1515/flih-2020-0006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gray RD, Atkinson QD: Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature. 2003;426(6965):435–439. 10.1038/nature02029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doornenbal M: A Grammar of Bantawa: Grammar, paradigm tables, glossary and texts of a Rai language of Eastern Nepal.PhD thesis, Leiden University,2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang B, Dai Q: A Tibeto-Burman Lexicon.Beijing: Central Minzu Univerisity,1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacques G: Dictionnaire Japhug-Chinois-Français.Paris: Projet HimalCo,2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li F: Xia-Han zidian [Tangut-Chinese dictionary].Beijing: China Social Sciences Press,1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai Y: Grammaire du khroskyabs de Wobzi.Paris: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris 3) dissertation,2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao Y: Description de la langue menya: phonologie et syntaxe.PhD thesis, École des hautes études en sciences sociales,2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang S: Le rgyalrong situ de Brag-bar et sa contribution à la typologie de l’expression des relations spatiales: l’orientation et le mouvement associé.PhD thesis, Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales,2020. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 13. Honkasalo S: A grammar of Eastern Geshiza.PhD thesis, University of Helsinki,2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang B: Lawurongyu yanjiu [Study on the Lavrung language].Beijing: Nationalities Press,2007. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yin W: Yelong Lawurongyu Yanjiu [Study on the ’Jorogs Lavrung language].Beijing: Nationalities Press,2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun JTS: Tshobdun Rgyalrong Spoken Texts With a Grammatical Introduction.Taipei: Academia Sinica,2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gong X: Le rgyalrong zbu, une langue tibéto-birmane de Cine du Sud-ouest. Une etude descriptive, typologique et comparative.PhD thesis, Paris: Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales,2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao H: A sketch of zlarong the newly discovered language: its phonology, lexicon, morphology and genealogy.Guanzhou: Sun Yat-Sen University master’s dissertation,2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prins M: A Grammar of rGyalrong, Jiˇaomùzú (Kyom-kyo) Dialects: A Wen of Relations.Brill,2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gates JP: Grammaire du stau de Mazur.Paris: Écoles des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales dissertation, 2021. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hill NW, List JM: Challenges of annotation and analysis in computer-assisted language comparison: A case study on burmish languages. Yearbook of the Poznan Linguistic Meeting. 2017;3(1):47–76. 10.1515/yplm-2017-0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hammarström H, Forkel R, Haspelmath M, et al. : Glottolog [Dataset, Version 4.7]. Zenodo.Geneva,2023. 10.5281/zenodo.7398962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forkel R, Hammarström H: Glottocodes: Identifiers linking families, languages and dialects to comprehensive reference information. Semantic Web. 2022;13(6):917–924. 10.3233/SW-212843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. List JM, Tjuka A, van Zantwijk M, et al. : Concepticon [Dataset, Version 3.1].Zenodo, Geneva,2023. 10.5281/zenodo.7777629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lai Y: Preinitial denasalisation and palatal fortition in khroskyabs and the gyalrongic word for ‘man’. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 2022;45(2):211–229. 10.1075/ltba.22006.lai [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Forkel R, List JM, Greenhill SJ, et al. : Cross-linguistic data formats, advancing data sharing and re-use in comparative linguistics. Sci Data. 2018;5(1):180205. 10.1038/sdata.2018.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. List JM, Hill NW, Foster CJ: Towards a standardized annotation of rhyme judgments in Chinese historical phonology (and beyond). Journal of Language Relationship. 2019;17(1–2):26–43. 10.31826/jlr-2019-171-207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anderson C, Tresoldi T, Chacon T, et al. : A cross-linguistic database of phonetic transcription systems. Yearbook of the Poznan Linguistic Meeting. 2018;4(1):21–53. 10.2478/yplm-2018-0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moran S, Cysouw M: The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles.Language Science Press,2018;145. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 30. List JM: A web-based interactive tool for creating, inspecting, editing, and publishing etymological datasets.In: Proceedings of the Software Demonstrations of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 2017;9–12. 10.18653/v1/E17-3003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. List JM: EDICTOR. A web-based interactive tool for creating, inspecting, editing, and publishing etymological datasets [Software Tool, Version 2.0.0].Zenodo, Geneva,2021. 10.5281/zenodo.4685130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Richard S, John B: The Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus: STEDT project data resources and protocols.University of California, Berkeley,2000. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nagano Y, Prins M: rGyalrongic Languages Database.National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka,2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schweikhard NE, List JM: Developing an annotation framework for word formation processes in comparative linguistics. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics. 2020;17(1):2–26. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu MS, List JM: Annotating cognates in phylogenetic studies of southeast asian languages. Language Dynamics and Change. 2023;1–37. 10.1163/22105832-bja10023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]