Abstract

Simian virus 40 (SV40)-infected CV1 cells transiently exposed to hypoxia show a burst of viral replication immediately after reoxygenation. DNA precursor incorporation and analysis of growing daughter strands by alkaline sedimentation demonstrated that SV40 DNA synthesis began with a lag of about 3 to 5 min after reoxygenation followed by a largely synchronous viral replication round. Viral RNA-DNA primers complementary to the SV40 origin region were not detectable before 3 min upon reoxygenation. A distinct form of circular closed, supercoiled SV40 DNA was detectable as soon as 3 min after reoxygenation but not under hypoxia. Sensitivity to the DNA nuclease Bal 31 and migration behavior in chloroquine-containing agarose gels suggested that this DNA species was highly underwound compared to other SV40 topoisomers and was probably related to the highly underwound form U DNA first described by Dean et al. (F. B. Dean, P. Bullock, Y. Murakami, C. R. Wobbe, L. Weissbach, and J. Hurwitz, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:16–20, 1987), in vitro. 3′-OH ends of presumed RNA-DNA primers could be detected in form U by 3′ end labeling with T7 polymerase. Addition of aphidicolin to the cells before reoxygenation led to a pronounced accumulation of form U DNA containing RNA-DNA primers. In vivo pulse-chase kinetic studies performed with aphidicolin-treated SV40-infected cells showed that form U is an initial intermediate of SV40 DNA replication which matures into higher-molecular-weight replication intermediates and into SV40 form I DNA after removal of the inhibitor. These results suggest that in vivo initiation of SV40 replication is arrested by hypoxia before origin unwinding and primer synthesis.

Reversible suppression of cellular replicon initiation in hypoxic mammalian cells seems to be a general mechanism adapting the intensity of DNA replication to the supply of O2 (and other nutrients) in the cellular environment (49, 50, 52, 54). The potential importance of this regulatory phenomenon in embryonic growth, tumor cell propagation, and wound healing has been mentioned previously (27, 28, 50, 52). A prominent feature of the O2-dependent regulation of replication is the short time span between reelevation of the pO2 to 20% (reoxygenation) and the emergence of a burst of new replicon initiations. This suggests that a signal depending on the actual pO2 exerts relatively direct control over a crucial step of replicon initiation. Examination of the molecular events leading from reoxygenation to replicon initiation in the mammalian cellular genome is, however, impeded by the great diversity of mammalian replicons, their poorly characterized origins, and a poor knowledge of the proteins involved in cellular initiation of DNA replication.

As we have shown previously (21), simian virus 40 (SV40) replication in virus-infected CV1 cells is also subjected to O2-dependent regulation of replicon initiation. Reduction of the pO2 to 0.02 to 0.2% in the culture medium results in reversible suppression of viral DNA replication. Reoxygenation after several hours of hypoxia triggers, within a few minutes, a burst of initiations followed by a nearly synchronous round of viral replication beginning at the viral origin of replication (21).

The initiation of SV40 DNA replication has been relatively well investigated, rendering this virus a useful model system to examine the reversible shutdown of replicon initiation by hypoxia.

Initiation of SV40 DNA replication requires the binding of a double hexamer of SV40 large T antigen to the viral origin in the presence of ATP, leading to structural distortions of the origin region (2, 3, 14, 15, 17, 41, 48; for a recent review about initiation of SV40 DNA, replication see reference 6). After binding of replication protein A (RPA), further local unwinding by the helicase activity of T antigen occurs (4, 33). The T antigen-RPA complex then binds polymerase α-primase, which synthesizes RNA-DNA primers at the unwound template (13, 20, 26). Succeeding processive elongation of RNA-DNA primers involves replication factor C, proliferating-cell nuclear antigen, and DNA polymerase δ (60, 61).

In principle, each of the mentioned steps could be prevented under hypoxia. However, comparing the time needed to constitute active initiation in SV40 replication systems in vitro (10 to 15 min) (59, 62, 64–66) with the time needed to activate the processive state of replication after reoxygenation (≤5 min) (21) suggests that part of the preinitiation and initiation process has already occurred under hypoxia.

In the present communication, we show that initiation of viral DNA replication under hypoxia is interrupted before unwinding of the origin region. We demonstrate the emergence of an early replicative form of SV40 DNA in vivo about 3 min after reoxygenation of host cells. We show that this replication intermediate is highly negatively supercoiled and probably related to the unwound form U SV40 DNA species that has been demonstrated by Dean et al. (16) to be formed in the course of SV40 initiation of replication in vitro. We further demonstrate that form U probably contains RNA-DNA primers in vivo and that it matures into SV40 Cairns intermediates and SV40 form I DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transient hypoxia, reoxygenation, and radioactive labeling.

Monkey CV1 cells (ATCC CCL70) were infected with SV40 as described previously (58). Transient hypoxia was started 24 h later by gassing with 0.02% O2–5% CO2–Ar to 100% for 10 h (21). For reoxygenation, 0.25 volume of medium equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2 was added and gassing was continued with artificial air (21). For radioactive labeling, [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine was added to the cells either directly or, for hypoxic labeling, by plunging a spatula carrying the appropriate quantity of [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine in dried form into the culture medium without interruption of the hypoxia.

Aphidicolin, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, was applicated to hypoxic cell cultures on a spatula after gassing within the hypoxic chamber for 15 min. The cells were reoxygenated 10 min after application of the inhibitor. To stop incubations, the culture supernatant was removed by aspiration and cells were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaHPO4 [pH 7.0]). Determination of incorporated radioactivity was described previously (53).

Alkaline sedimentation analysis of labeled SV40 DNA.

SV40-infected cells were pulse-labeled for 6 min before or after reoxygenation with 20 μCi of [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine. After being washed, the cells were lysed in 0.25 M NaOH for 1 h and layered onto a 5 to 40% linear sucrose gradient in 0.25 M NaOH–0.6 M NaCl–1 mM EDTA–0.1% sodium lauroylsarcosinate. After centrifugation in a Beckman SW40 rotor at 36,000 rpm at 23°C for 16 h, 0.6-ml fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and analyzed for acid-insoluble radioactivity (53).

Isolation of RNA-DNA primers and correlation with the SV40 genome.

For separation of RNA-DNA primers from cellular and viral bulk DNA, an improved version of a hydroxyapatite thermochromatography method was used, as described previously (53), to separate short-chain replication intermediates from bulk DNA in Ehrlich ascites cells. The procedure consists of two main steps: (i) preparation of a crude cell lysate under conditions partially destabilizing the DNA double helix in order to melt out all single chains shorter than about 200 nucleotides, and (ii) elimination of all double-stranded DNA from the lysate by passage through a hydroxyapatite column. The details are as follows. Four SV40-infected cell cultures were cultivated hypoxically for 10 h. One of the cultivations was stopped before reoxygenation. The others were reoxygenated and the reactions were stopped 3, 5, or 10 min after reoxygenation. Labeling with [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (50 μCi/ml) was performed as described in the legend of Fig. 2. The cells were lysed for 5 min in 4 M guanidinium thiocyanate–0.12 M guanidinium phosphate (pH 6)–0.2% sodium lauroylsarcosinate–1 mM EDTA (1 ml), and DNA was sheared by 10 passages through a 26-gauge injection needle. The lysate was prewarmed to 37°C for 10 min and loaded onto a hydroxyapatite column (10 by 45 mm) that had been equilibrated with 4 M guanidinium thiocyanate–0.12 M guanidinium phosphate (pH 6) and prewarmed to 37°C. The flowthrough and the eluates obtained after washing the column twice with 0.5 ml of 4 M guanidinium thiocyanate–0.12 M guanidinium phosphate at 37°C were combined and dialyzed overnight against 10 mM NaCl–0.1 mM Tris–0.01 mM EDTA–0.2% sodium lauroylsarcosinate (pH 7.5).

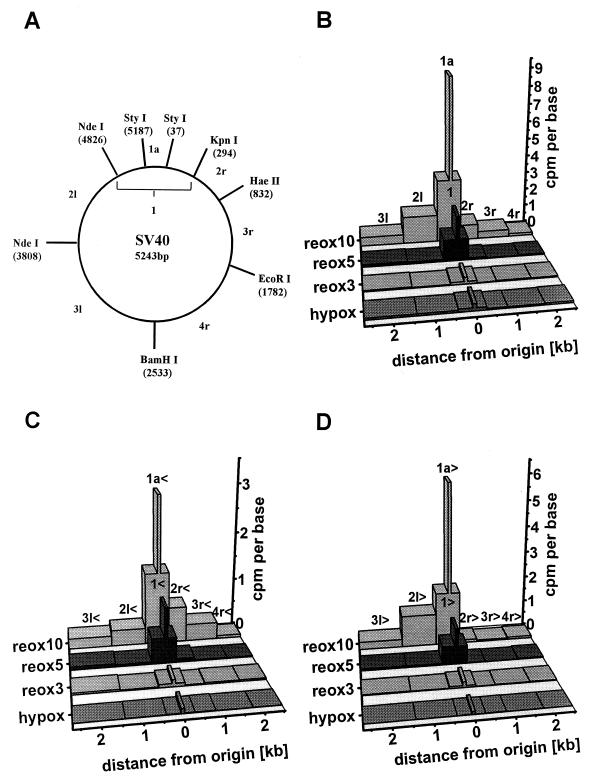

FIG. 2.

Hybridization of RNA-DNA primers, labeled with [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine in vivo, to a set of membrane-fixed single-stranded, SV40-specific probes. Preparation of the RNA-DNA primers fraction from hypoxic or reoxygenated SV40 infected cells was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Designations and labeling schedules of analyzed samples: hypox, [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (50 μCi/ml) was added at the start of hypoxia and incubation was stopped after 10 h; reox3, reox5, [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (50 μCi/ml) was added after 9.5 h of hypoxic incubation to the cells, and incubation was continued for 30 min, and the cells were then reoxygenated and incubated with artificial air for 3 or 5 min; reox10, cells were reoxygenated after 10 h of hypoxia and labeled 2 min later with [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (50 μCi/ml) for 8 min. (A) Cleavage sites of restriction enzymes used to generate a set of SV40-specific single-stranded DNA probes. Restriction fragments 1 and 1a harbor the origin of replication. The other fragments are either situated rightward (2r, 3r, and 4r) or leftward (2l, 3l) with respect to the viral origin. After subcloning, each restriction fragment yields two complementary single-stranded probes which recognize either sense sequences (probes marked by <) or antisense sequences (probes marked by >) of late viral mRNAs. (B) Sum of radioactivity hybridized to the respective < and > probes. (C) Radioactivity hybridized to the < probes alone. (D). Radioactivity hybridized to the > probes alone.

The dialysate was subsequently hybridized against membrane-fixed, single-stranded M13mp18 DNA containing segments of the SV40 genome (see Fig. 2A) cloned in either direction into the plasmid SmaI site by standard procedures (57). For fixation of the single-stranded SV40 probes onto a nylon membrane, 400 ng of DNA was dissolved in 200 μl of SSC (0.3 M NaCl, 0.03 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0]), heated to 65°C for 10 min, and chilled on ice. The DNA was then transferred to the membrane (2 cm in diameter), dried at 37°C, and fixed by UV irradiation. Hybridization was performed at 37°C as described previously (19). After hybridization, the radioactivity bound to each of 14 probes was quantified and normalized for the size of the respective SV40 segment.

DNA isolation, chloroquine gel electrophoresis, Southern blotting, and hybridization.

Washed cells were lysed and digested (0.25 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% sodium lauroylsarcosinate, 100 μg of proteinase K per ml) for 3 h at 55°C. The lysate was extracted twice with phenol-CHCl3 and dialyzed against 0.1× Tris-EDTA (TE; pH 8.0) at 4°C overnight. After digestion with RNase A (100 μg/ml at 37°C for 1 h), 100 ng of isolated DNA per slot was loaded onto a 25- by 20-cm agarose gel containing 70 μg of chloroquine per ml of gel buffer (30 mM NaH2PO4, 36 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA). Electrophoresis was carried out at 2 V/cm and 4°C for 20 h. Southern blotting was performed subsequently under alkaline conditions as described previously (57). 32P labeling of BamHI-linearized SV40 DNA was performed with the Boehringer random-primed DNA-labeling kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Hybridization was performed as described previously (19).

Distribution of SV40 DNA labeled in vivo by [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine and separated by chloroquine electrophoresis was determined by cutting single lanes of the gel into 0.8-cm slices, which were dissolved in 0.5 M HCl (1 ml) by heating to 80°C for 2 h and counted after addition of 10 ml of Ultima gold scintillator (Amersham Buchler, Braunschweig, Germany).

Isolation of SV40 topoisomers, Bal 31 digestion, and chloroquine gradient gel-electrophoresis.

Whole-cell DNA of SV40-infected CV1 cells was isolated 5 min after reoxygenation and electrophoresed on a preparative low-melting-point agarose gel (NuSieve GTG agarose; Biozym, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany) containing 70 μg of chloroquine/ml as described above. For localization of SV40 topoisomers, one lane of the gel was Southern blotted and hybridized against 32P-labeled SV40 DNA. DNA from bands representing separated topoisomers was then prepared from the rest of the gel as described previously (57). For preparation of relaxed closed circular double-stranded SV40 DNA, virus-infected cells were grown euoxically in the presence of camptothecin (10 μM) for 30 min. After separation of whole-cell DNA on a chloroquine-containing low-melting-point agarose gel (70 μg/ml), the additional fast-migrating band which turned out to be relaxed closed circular SV40 DNA was isolated as described above. Digestion with nuclease Bal 31 was performed at 30°C for 30 min as described previously (57).

For evaluation of negative supercoiling, SV40 topoisomers were separated on gradient gels prepared by successively gelling 11 agarose lanes containing increasing chloroquine concentrations between two glass plates (11 by 14 cm). The conditions of electrophoresis were the same as described above, but the buffer contained no chloroquine and the running time was only 4 h. Topoisomers were detected by Southern blotting and hybridization against 32P-labeled SV40 DNA as described above.

Labeling of 3′-OH ends in replicative SV40 DNA molecules.

Washed CV1 cells were lysed and digested (0.25 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% sodium lauroylsarcosinate, 100 μg of proteinase K/ml) for 3 h at 37°C. The lysate (200 μl) was extracted twice with phenol-CHCl3 and loaded onto a 15 to 30% linear neutral sucrose gradient (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 15 to 30% sucrose). After centrifugation in a Beckman SW60 rotor for 15 h at 30,000 rpm and 4°C, 0.5-ml fractions were taken and aliquots of 20 μl were analyzed for SV40 DNA on an agarose gel. Positive fractions were pooled, and DNA was sedimented by centrifugation for 4 h in a Beckman TLA 100.2 rotor at 100,000 rpm and 4°C. After the run, the supernatant was rapidly removed by aspiration and the SV40 DNA was dissolved in 10 μl of TE (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl.

To label the 3′-OH ends of base-paired DNA chains, 50 to 250 ng of the dissolved SV40 DNA was elongated with Sequenase version 2.0 (3 U) (United States Biochemicals, Braunschweig, Germany) in the presence of dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP (300 nM each) and [α-32P]ddATP (10 μCi, 3,000 Ci/mmol) in 7.5 mM dithiothreitol–30 mM NaCl–30 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–15 mM MgCl2 in a volume of 10 μl for 10 min at room temperature and another 5 min at 37°C.

After being end labeled, the DNA was analyzed by separation on chloroquine-containing gels, capillary blotting to a nylon membrane, and direct autoradiography. For determination of the size of labeled single strands, the end-labeling mixture was brought to 50% (vol/vol) formamide, 2.5 mM EDTA, and 0.05% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue and DNA was denatured by heating to 80°C for 10 min. The DNA was then separated at 600 V for 3 h on a 20% polyacrylamide–Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gel containing 6 M urea. After the run, the gel was directly autoradiographed.

RESULTS

DNA replication begins after a short lag upon reoxygenation.

As we have shown previously (21), initiation of SV40 DNA replication very closely succeeds reoxygenation of hypoxically cultivated virus-infected CV1 cells. Incorporation of [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine added shortly before reoxygenation into viral DNA first started 2 to 3 min after reoxygenation (curve not shown). A similar lag between reoxygenation and the onset of DNA replication was observed in Ehrlich ascites cells (54). To examine the chain lengths of the DNA synthesized after reoxygenation, SV40-infected cells were labeled with [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine by 6-min pulses staggered around the time of reoxygenation. The labeled DNA was then analyzed for size by alkaline sucrose gradient centrifugation. Previous experiments (results not shown) revealed that more than 90% of the acid-precipitable radioactivity was incorporated into viral DNA. Therefore, we generally did not prepare Hirt supernatants, in which different but generally large portions of replicative viral DNA are lost.

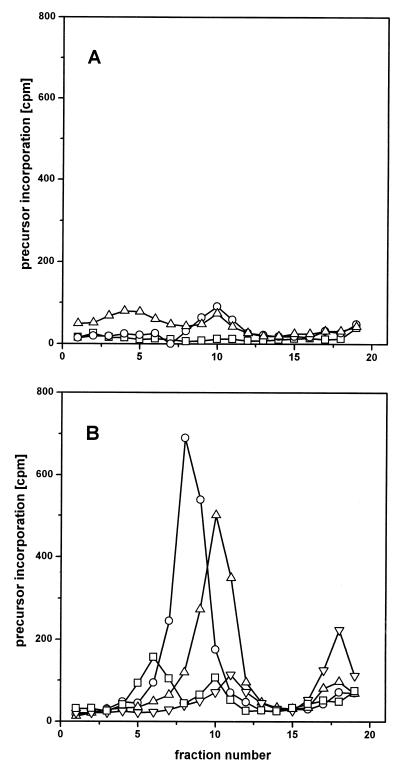

Significant incorporation of [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine into newly initiated growing chains (fractions 4 to 9) occurred not earlier than 3 min after reoxygenation but did not occur under hypoxia (Fig. 1A). Some radioactivity was recovered as nearly full-length SV40 DNA (fractions 10 and 11) when the labeling by [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine included the first 2 min after reoxygenation. This radioactivity probably represented DNA molecules engaged in replication when the preceding hypoxia became effective (21). At 3 to 5 min after reoxygenation, a nearly synchronous round of viral replication started, indicated by the increasing shift of labeled molecules to higher S values with increasing time (Fig. 1B). Covalently closed SV40 DNA, accumulating in the bottom fractions of the gradients, was first detected when the end of the labeling period was shifted to 16 min after reoxygenation.

FIG. 1.

Alkaline sucrose gradient centrifugation of viral DNA from hypoxically cultivated and reoxygenated SV40-infected CV1 cells. Cells were cultivated hypoxically for 10 h and incubated with [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (20 μCi/ml) either before or after reoxygenation between the points of time indicated (0 = time of reoxygenation). (A) □, −6 to 0 min (hypoxic); ○, −4 to +2 min; ▵, −3 to +3 min; (B) □, −1 to +5 min; ○, +2 to +8 min; ▵, +10 to +16 min; ▿, +20 to +26 min. Sedimentation was from left to right. Supercoiled viral DNA is collected in the bottom fractions (fractions 17 to 19).

Synthesis of RNA-DNA primers is not detectable under hypoxia.

The very first nucleic acid polymerized after completion of the preinitiation phase consists of short RNA-DNA primers formed by polymerase α-primase (6, 13, 20, 26). Subsequent processive primer elongation requires loading of replication factor C and proliferating-cell nuclear antigen and switching to polymerase δ (6, 46, 60, 61). We asked whether hypoxia prevented either primer formation or switching to processive DNA synthesis. In the first case, primers would first emerge after reoxygenation; in the second, primers would accumulate under hypoxia. To distinguish between the possibilities, [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine was added to SV40-infected CV1 cells concurrently with the start of hypoxic gassing or shortly before or after reoxygenation. Primer-sized DNA (i.e., DNA smaller than 200 bp melted out from hydroxyapatite-bound bulk DNA in the form of small, single-stranded chains, as described in Materials and Methods) was isolated from hypoxic or reoxygenated cell cultures and hybridized to a set of membrane-fixed single-stranded SV40 probes. As shown in Fig. 2A, this set covers the complete SV40 genome and differentiates between the respective complementary strands. Primer-sized labeled DNA isolated from hypoxic cells and from cells whose reaction was stopped 3 min after reoxygenation carried minimal radioactivity, which was bound more or less uniformly to all probes in the set (Fig. 2B to D).

RNA-DNA primers isolated from cells labeled until 5 min after reoxygenation preferentially hybridized to probes containing the viral origin (Fig. 2, probes 1 and 1a). When the incubation lasted until 10 min after reoxygenation, a large amount of RNA-DNA primers was still bound to probes 1 and 1a but also to probes containing SV40 regions more distant from the viral origin (probes 2r, 2l, 3r, and 3l). The primer fractions isolated from the cells labeled until 10 min after reoxygenation exhibited the expected leading- versus lagging-strand differences of binding to the different probes of the set (Fig. 2C and D).

Primer-sized labeled DNA isolated from uninfected CV1 cells was not bound at all to the SV40 probes (data not shown).

The results presented show that primer synthesis is not detectable before 3 min after reoxygenation. This indicates that initiation of SV40 replication in hypoxic cells is not interrupted at primer elongation but rather at primer synthesis or at a preceding initiation step (e.g., assembly of initiation proteins at the SV40 origin or unwinding of the origin region).

A highly underwound SV40 DNA species appears within 3 min after reoxygenation.

Since RNA-DNA primers were not detectable before or shortly after reoxygenation, we next examined how origin unwinding was influenced by hypoxia and reoxygenation. As shown for SV40 origin-containing plasmids in vitro (7, 16, 66), unwinding generates topological DNA isomers which, after deproteinization, are detectable in chloroquine-containing agarose gels due to their enhanced degree of negative supercoiling compared to the nonreplicative SV40 topoisomers.

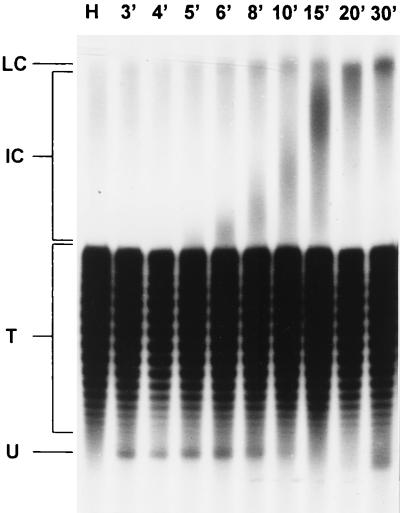

Whole-cell DNA of hypoxic or reoxygenated SV40-infected cells whose incubation was stopped at different times after reapplication of O2 was isolated and electrophoresed on a chloroquine-containing agarose gel. After Southern blotting, the DNA was hybridized to a 32P-labeled SV40 probe. An additional, fast-migrating SV40 topoisomer (termed form U in the nomenclature of 16) was detectable between 3 and 8 min after reoxygenation (Fig. 3). Form U was not detectable under hypoxia or beyond 8 min after reoxygenation (Fig. 3). Further experiments (results not shown) revealed that form U DNA did not emerge before 2 min after reoxygenation. Addition of camptothecin (10 μM) to the cells just before reoxygenation suppressed the appearance of form U, suggesting that topoisomerase I is involved in its formation (data not shown). Cairns intermediates, running through a nearly synchronous round of replication, were detectable after 5 to 6 min of reoxygenation as an increasingly slower-migrating band emerging out of the bulk of nonreplicative topoisomers. After 20 to 30 min, late Cairns intermediates with a defined low electrophoretic mobility developed. The fact that form U disappeared as increasingly later replication intermediates began to dominate further indicated its significance as an initial intermediate of SV40 replication.

FIG. 3.

Demonstration of form U after reoxygenation. SV40 DNA was isolated from hypoxically cultivated and reoxygenated CV1 cells and separated on a chloroquine-containing agarose gel. After Southern blotting, the DNA was hybridized against 32P-labeled linear SV40 DNA. Lanes: H, 10-h hypoxic; 3′ to 30′; reoxygenated (times, in minutes, after reoxygenation are indicated). LC, late Cairns SV40 DNA; IC, intermediate Cairns SV40 DNA; T, topoisomers of mature SV40 DNA (form I); U, form U.

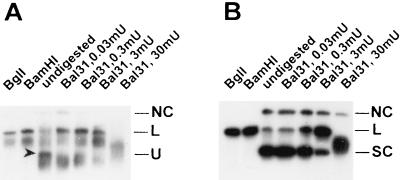

To demonstrate that form U is indeed a full-length, highly negatively supercoiled SV40 topoisomer, it was isolated from a preparative chloroquine-containing agarose gel. Portions (0.1 to 0.2 ng) of form U DNA were digested with BamHI or BglI or with increasing amounts of single-strand-specific nuclease Bal 31 and electrophoresed on minigels. SV40 DNA was detected in the gel blots by hybridization as described above. Digestion with restriction nucleases revealed that form U represents a full-length supercoiled SV40 topoisomer (Fig. 4A). Compared to another supercoiled SV40 topoisomer (Fig. 4B) (the same topoisomer as analyzed in Fig. 5D), form U was found to be 10 to 100 times more sensitive to digestion with Bal 31. This result suggests that form U exhibits extensive single-strand-like character, as expected for highly negatively supercoiled DNA. Moreover, cleavage of form U by Bal 31 led directly to the linear form III SV40 DNA, and only a minor amount of circular nicked (form II) DNA was detectable. As described previously (29, 38), this digestion pattern points to the presence of a cruciform structure in form U, which is preferably cut in the loops by Bal 31, leading to linear SV40 DNA. This cruciform structure may be extruded from the SV40 origin inverted repeat in case of high negative superhelical tension (38).

FIG. 4.

Digestion of form U (A) and a supercoiled SV40 DNA topoisomer (B) with endonucleases BglI and BamHI and sensitivity against the single-strand-specific DNase Bal 31. A total of 0.1 (BglI and BamHI) or 0.2 ng (Bal 31) of each topoisomer was digested. NC, nicked circular DNA; L, linear DNA; SC, supercoiled DNA; U, form U (also indicated by an arrowhead).

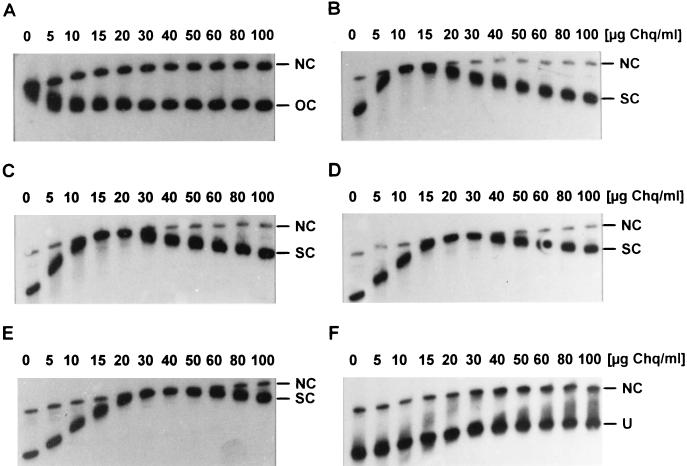

FIG. 5.

Migration pattern of distinct SV40 topoisomers in chloroquine (Chq) gradient gel electrophoresis. Gradient gels consist of 11 layers of different chloroquine concentrations as indicated at the top of the photographs. Different topoisomers at 0.1 to 1 ng were loaded. NC, nicked circular DNA; OC, relaxed closed circular DNA; SC, supercoiled DNA; U, form U. (A) Relaxed, closed circular SV40 DNA; (B to E) SV40 DNA topoisomers with increasing preexisting negative superhelical tension; (F) form U.

The negative supercoil densities of form U and selected bulk SV40 DNA topoisomers were also compared by determination of the migration behavior in agarose gels containing increasing amounts of chloroquine in neighboring lanes (Fig. 5).

Depending on the preexisting negative superhelical tension, the minima of electrophoretic mobility, indicating the point where the DNA circle is relaxed, were reached at different chloroquine concentrations for each topoisomer (Fig. 5A to E). Note the different migration pattern of relaxed closed circular and relaxed nicked circular SV40 DNA in Fig. 5A: upon intercalation, chloroquine introduces positive supercoils in closed but not in nicked circles, causing increased versus decreased mobility, respectively, with rising chloroquine concentrations.

The minimum electrophoretic mobility was not reached for form U at chloroquine concentrations up to 100 μg/ml (Fig. 5F), again confirming a very high degree of preexisting negative supercoiling for this SV40 topoisomer. Increasing the chloroquine concentration to 300 μg/ml caused a significant reduction of form U mobility (data not shown); it was also found that form U migrated as a smear instead of a sharp band at this concentration, indicating that form U probably consists of many SV40 topoisomers with different elevated degrees of negative supercoiling. The electrophoretic separation was, however, poor at this and higher chloroquine concentrations.

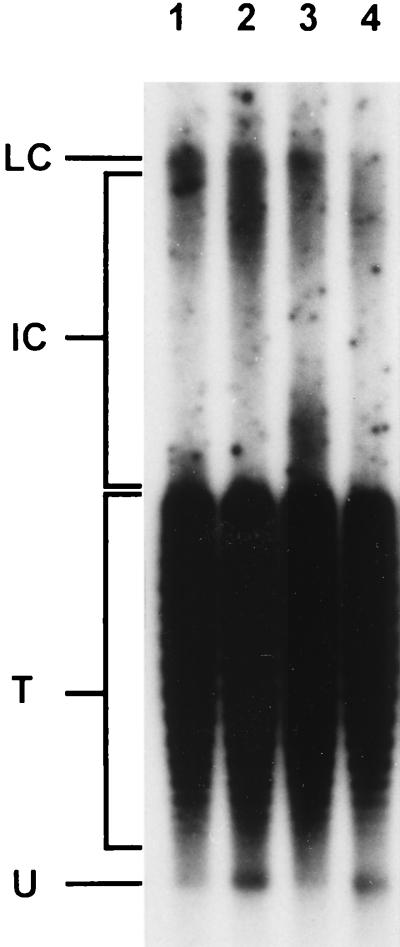

Aphidicolin induces the accumulation of form U.

Aphidicolin, an inhibitor of polymerases α and δ, inhibits primer processing (47) and probably uncouples helicase and replicative polymerase activities (22). When aphidicolin (2 μg/ml) was added to hypoxic cells 10 min before reoxygenation, accumulation of form U was detectable 4 and 7 min after reoxygenation (Fig. 6). Cairns intermediates were not observed in aphidicolin-treated cells. These results again suggest that form U is a precursor of replicative SV40 DNA forms.

FIG. 6.

Accumulation of SV40 form U in reoxygenated cells treated with aphidicolin. Aphidicolin (2 μg/ml) was added to SV40-infected CV1 cells 10 min before reoxygenation. SV40 DNA was isolated, separated on a chloroquine-containing gel, Southern blotted, and hybridized as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, control, 4-min reoxygenated; 2, plus aphidicolin, 4-min reoxygenated; 3, control, 7-min reoxygenated; 4, plus aphidicolin, 7-min reoxygenated. LC, late Cairns SV40 DNA; IC, intermediate Cairns SV40 DNA; T, topoisomers of mature SV40 DNA (form I); U, form U.

Form U probably contains RNA-DNA primers.

In a previous publication (47), Nethanel et al. showed that aphidicolin inhibits primer processing but not primer synthesis in isolated nuclei of SV40-infected cells. We therefore investigated whether RNA-DNA primers were also detectable in SV40 DNA of cells treated with aphidicolin before reoxygenation.

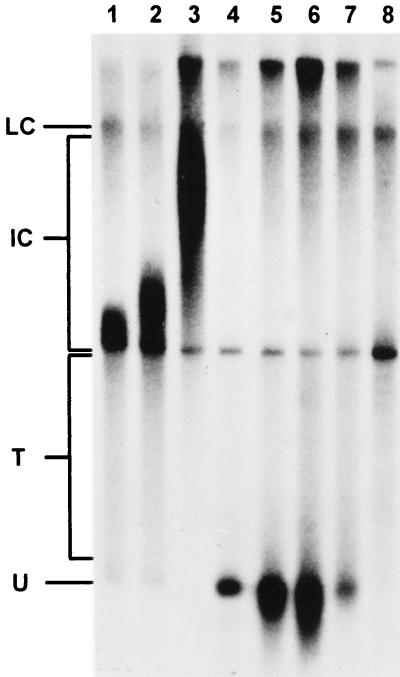

SV40 DNA was separated from the remainder of the DNA by neutral sucrose gradient centrifugation, and 3′-OH ends of base-paired chains were labeled and elongated by a few nucleotides with T7-DNA polymerase (Sequenase), [α-32P]-ddATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP. Labeled DNA was subsequently separated on a chloroquine-containing agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane by capillary blotting, and autoradiographed. In untreated cells (Fig. 7, lanes 1 to 3), form U was slightly labeled. Cairns intermediates, again detectable as an increasingly slower migrating band, were more strongly labeled. As expected, essentially no radioactivity was found in the range of the nonreplicating SV40 DNA topoisomers. Addition of aphidicolin (lanes 4 to 6) led to strong labeling of form U, whereas essentially no radioactivity was found in the range of the Cairns intermediates. Longer incubation times in the presence of the inhibitor resulted in a downward broadening of the form U signal. When aphidicolin was washed out 6 min after reoxygenation (lanes 7 and 8), the label in the form U region disappeared and moved to the early Cairns intermediate region. Again, the range of the bulk topoisomers remained essentially free of radioactivity. The end-labeled DNA chains were also analyzed on a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 6 M urea. In SV40 DNA isolated from aphidicolin-treated cells, end-labeled chains in the range of 25 and about 50 nucleotides (nt) were found (Fig. 8). When end-labeled DNA was treated with NaOH (0.3 M) at 60°C for 40 min prior to electrophoresis, a size reduction of primer-sized DNA was observed, suggesting that the end-labeled strands contained RNA synthesized by primase (initiator RNA [iRNA]) (Fig. 8). The 3′-end-labeled DNA isolated from control cells 4 min after reoxygenation was found to be up to 200 nt. Again, NaOH treatment led to size reduction (data not shown). As expected, no shortening was seen when the isolated 67-bp band of the molecular weight marker was treated with NaOH (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Analysis of 3′-OH end-labeled SV40 DNA isolated from untreated and aphidicolin-treated CV1 cells. SV40-infected CV1 cells were reoxygenated in the absence (lanes 1 to 3) or presence (lanes 4 to 8) of aphidicolin (2 μg/ml). After reoxygenation, the cells were incubated for the indicated times or aphidicolin was washed out after 6 min (lanes 7 and 8). SV40 DNA was separated from cellular DNA and 3′-OH end labeled with [α-32P]ddATP as described in Materials and Methods. End-labeled DNA was separated on a chloroquine-containing gel, capillary blotted, and autoradiographed. Lanes: 1, control, 4-min reoxygenated; 2, control, 7-min reoxygenated; 3: control, 16-min reoxygenated; 4 to 6, as lanes 1 to 3, with aphidicolin; 7, aphidicolin removed 6 min after reoxygenation, incubated for a further 2 min; 8, aphidicolin removed 6 min after reoxygenation, incubated for a further 6 min. LC, late Cairns SV40 DNA; IC, intermediate Cairns SV40 DNA; T, topoisomers of mature SV40 DNA (form I); U, form U.

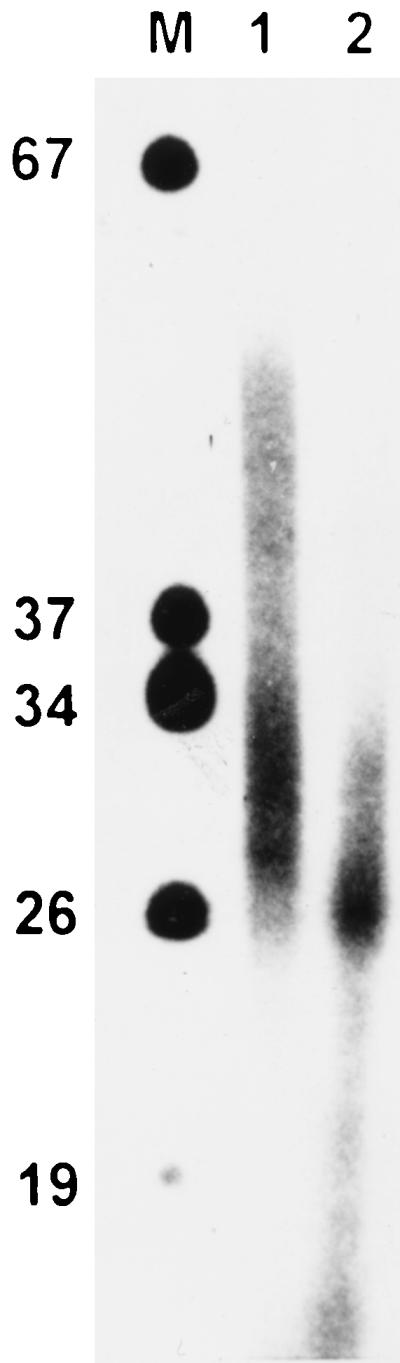

FIG. 8.

Demonstration of RNA-DNA primers in SV40 DNA isolated from aphidicolin-treated CV1 cells. SV40 DNA from cells reoxygenated for 11 min in the presence of aphidicolin (2 μg/ml) was isolated and 3′-end labeled as described in Materials and Methods. The DNA was then separated on a 20% polyacrylamide–6 M urea gel. DNA from lane 2 was incubated with 0.3 M NaOH at 60°C for 40 min to hydrolyze iRNA before electrophoresis. M, 5′-end-labeled marker DNA (DNA molecular weight marker VIII [Boehringer]).

Form U matures into Cairns intermediates and full-length SV40 topoisomers.

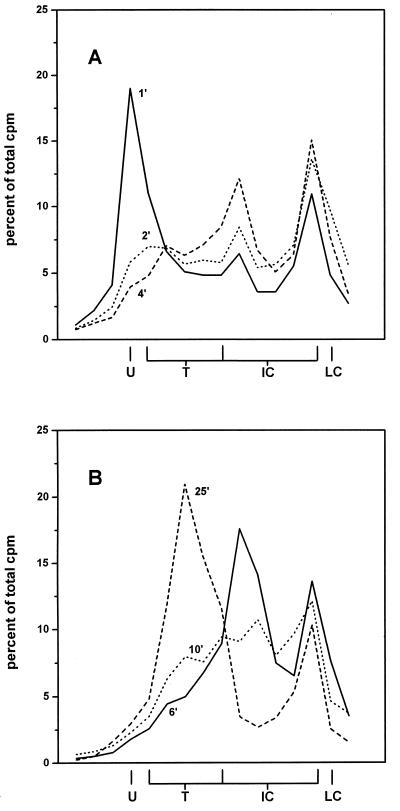

The disappearance of form U and the concomitant appearance of early Cairns intermediates after removal of aphidicolin, as shown in Fig. 8, is a strong hint that form U is a precursor of replicative SV40 DNA species. This was further confirmed by chase kinetics of a 3H label incorporated into form U in vivo. SV40-infected cells were treated with aphidicolin (2 μg/ml) and [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (80 μCi/ml) 10 min before reoxygenation. At 6 min after reoxygenation, the medium was replaced by chase medium containing 10 μM nonlabeled deoxythymidine and no aphidicolin, and incubation was continued for various times. DNA was isolated and separated on a chloroquine-containing gel. After the run, the gel was cut into slices, which where analyzed for radioactivity. Figure 9A shows that 1 min after replacement of the aphidicolin–[methyl-3H]deoxythymidine-containing medium by the chase medium, most of the label was found at the position of form U, which was localized by Southern blotting and hybridization of a separate lane of the gel. With increasing times, the label of form U was chased into Cairns intermediate DNA and finally into the mature topoisomers of SV40 DNA (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

Chase kinetics of a radioactive label incorporated into SV40 form U in vivo. [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (70 μCi/ml) and aphidicolin (2 μg/ml) were added to SV40-infected cells 10 min before reoxygenation. At 6 min after reoxygenation, the medium was replaced by chase medium containing 10 μM deoxythymidine and incubation was continued for the indicated times. SV40 DNA was isolated and separated on a chloroquine-containing gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was cut into slices, which were analyzed for containing 3H radioactivity. (A) Distribution of the 3H label after a chase of 1, 2, or 4 min. (B) Distribution of the 3H label after a chase of 6, 10, or 25 min. LC, late Cairns SV40 DNA; IC, intermediate Cairns SV40 DNA; T, topoisomers of mature SV40 DNA (form I); U, form U.

DISCUSSION

The cellular replicons of Ehrlich ascites cells and the viral replicons in SV40-infected cells exhibit distinct analogies with respect to their behavior in transient-hypoxia experiments. Like cellular replicons, SV40 replicons accumulate under hypoxia in a state ready to begin DNA synthesis immediately after reoxygenation (21). The present study was intended to elucidate, by means of the SV40 model, some mechanistic aspects of these remarkably fast responses. In particular, we investigated the state in which replicon initiation is blocked under hypoxia, ready to be reactivated immediately after O2 recovery.

The results presented suggest that hypoxia blocks initiation at a stage preceding origin unwinding and primer synthesis. Unwinding was demonstrated by the appearance of a highly underwound SV40 DNA species, termed form U (16), in chloroquine-containing agarose gels. Form U was detected between 3 and 8 min after reoxygenation but was not detected under hypoxia (Fig. 3). Comparison of the electrophoretic mobility of form U with that of other SV40 topoisomers in special agarose gels containing different chloroquine concentration in neighboring lanes (Fig. 5) indicated that form U is highly underwound. This agrees with the in vitro results of Bullock et al. (7) and Dean et al. (16).

In vitro, origin unwinding was shown to depend on SV40 T antigen, RPA, a topoisomerase, and ATP (16, 33). Upon binding of T antigen to the viral origin, local distortion occurs, resulting in one to five additional negative superhelical turns (55). Such small changes in overall superhelical density are, however, difficult to detect in vivo, since they will be masked by the naturally occurring variations of negative supercoiling in the large excess of nonreplicative bulk SV40 DNA present (Fig. 3). It therefore remains uncertain whether this minor initial distortion occurs before or after reoxygenation.

Additional unwinding generates form U, which is detectable in chloroquine-containing gels (7, 16). In an in vitro replication assay mixture containing T antigen, HeLa cytoplasmic extract, ATP, and an ATP-regenerating system, form U was detected 5 to 10 min after mixing of the components (7). DNA synthesis was detectable not earlier than 15 min after the start of incubation. These results suggest that unwinding is not necessarily followed by an immediate start of DNA synthesis. In our in vivo experiments, form U appeared 3 min after reoxygenation (Fig. 3). This relatively short time suggests that part of the preinitiation process, most probably T-antigen binding to the viral origin, takes place despite the presence of hypoxia. This suspicion is confirmed by recent data which indicate that the T antigen is bound to the origin prior to reoxygenation (to be published separately in another context). RNA-DNA primers and subsequent processive DNA elongation were detectable 3 to 5 min (Fig. 1 and 3) after reoxygenation, i.e., very shortly after or even at the same time as the generation of form U. The 3′-OH end labeling of SV40 DNA isolated from reoxygenated cells (Fig. 7) showed that form U indeed contains RNA-DNA primers. This result was especially evident when the cells were treated with aphidicolin immediately before reoxygenation (Fig. 7). Previous analysis by Dröge et al. (22) showed that aphidicolin induces negative supercoiling in SV40 DNA in vivo. It was concluded that helicase and polymerase activities are uncoupled to some extent by aphidicolin. Nethanel et al. (47) showed that primer synthesis is not compromised by aphidicolin in isolated nuclei of SV40-infected cells but, instead, primer processing is inhibited. Both statements are supported by the results presented here. After aphidicolin treatment, RNA-DNA primers of the same size as described by Nethanel et al. (47) (i.e., 30 to 60 nt [Fig. 8]) were found in the isolated SV40 DNA. Cairns intermediates, indicating normal processing of RNA-DNA primers to higher-molecular-weight daughter strands, on the other hand, were not observed even 16 min after reoxygenation. Primer loss, as reported by Nethanel et al. (47) to occur in isolated nuclei after prolonged aphidicolin treatment, was not detectable.

Aphidicolin also led to an increase in the amount of form U DNA detectable by Southern hybridization (about a fivefold increase compared to an untreated control, as judged by densitometric evaluation of Fig. 6). At the same time, the overall number of primer 3′-OH ends detectable by end labeling increased from about 10-fold 4 min after reoxygenation to >40-fold 16 min after reoxygenation compared to the untreated control (Fig. 7). This result suggests that the number of free 3′-OH-ends per molecule of form U probably increased with increasing incubation times in presence of aphidicolin, indicating that unwinding and concomitant primer synthesis continued in aphidicolin-treated cells whereas primer processing was inhibited.

Prolonged treatment with aphidicolin resulted in a broadening of the form U band (Fig. 7). This may also be interpreted as a further unwinding of form U, leading, after deproteinization, to additional negative supercoiling and higher electrophoretic mobility in chloroquine gels. Downward broadening was also observed in vitro with a distinct species of form U (termed form UR) when RPA was added in excess to the reaction mixture (7). This was also interpreted as a further unwinding of form UR.

When aphidicolin was removed from reoxygenated cells, form U disappeared and Cairns intermediates and mature SV40 topoisomers emerged (Fig. 7 and 9), indicating that form U is a precursor of replicative SV40 DNA forms.

The results presented here suggest that form U is derived from an in vivo SV40 DNA species, which is unwound to a certain degree and contains some RNA-DNA primers but also significant complementary single-stranded regions, probably coated by RPA. After deproteinization, the latter generate the additional negative supercoils responsible for the high electrophoretic mobility of form U in chloroquine-containing gels.

RNA-DNA primers of the size observed in Fig. 8 are expected to be thermally stably bound under the conditions used to isolate form U (57), and primer loss is energetically unfavorable because it further increases the existing negative supercoiling generated by elimination of nucleosomes and RPA. Nevertheless, it cannot be fully excluded that some primer loss during DNA isolation is involved in generation of the particular high degree of negative supercoiling typical of form U. However, we do not believe that this is the case. It should be noted in this context that there is a difference between primer loss in isolated nuclei as described by Nethanel et al. (47), which may be compensated by topoisomerase I action or RPA binding, and primer loss during DNA isolation, which necessarily results in additional negative superhelical tension.

As mentioned above, form U generation in vitro is not necessarily accompanied by simultaneous primer synthesis. In vivo, unwinding and form U generation seems to be directly accompanied by primer synthesis. This may point to a tighter coupling of unwinding and primer synthesis by DNA polymerase α-primase compared to the in vitro assay.

The differences mentioned raise the question of how far observations made in in vitro systems reflect the in vivo situation. Because a method for synchronizing SV40 replicon action within living cells had so far not been developed, the knowledge about the temporal organization of replicon initiation exclusively relied on experiments with in vitro systems. Such systems per se provide a certain synchrony, since mixing of crucial system components defines a temporal reference point. However, bringing together previously well-separated components of a complex macromolecular machinery is by no means a physiological event. Transient-hypoxia experiments with cultivated cells, in contrast, provide a tool to synchronize cellular or viral replicon action. In cells exposed to “controlled-hypoxia” (5) conditions, cellular or viral replicons accumulate in a distinct, still uninitiated state, ready to be released into a synchronous round of replication by a physiological switch.

The mechanism by which reoxygenation triggers the unwinding of the viral origin is unknown. Some possibilities seem unlikely or even may be excluded, especially if it is assumed that events leading from reoxygenation to initiation are essentially the same for mammalian and SV40 replicons. ATP was found not to be under short supply in hypoxic Ehrlich ascites (51, 52) or SV40-infected CV1 cells (unpublished data). Moreover, addition of KCN (10 mM) to hypoxic cells just before reoxygenation did not suppress the appearance of form U DNA (data not shown).

With respect to the replication of cellular DNA of Ehrlich ascites cells, it was already pointed out that the fast and reversible response of the replication machinery to transient hypoxia cannot be interpreted as a p53-dependent phenomenon mediated by changes in the expression of p21 (5). For SV40 replication in vivo, a p53-dependent pathway can be excluded a priori, since this protein is bound and thus inactivated by the large T antigen (25, 35, 36). Finally, synthesis of new proteins seems not to be possible in the short period between reoxygenation and the beginning of DNA synthesis.

Among the remaining possibilities, changes in the phosphorylation patterns of proteins directly involved in origin unwinding or primer synthesis seem to be most likely. For SV40 T antigen, phosphorylation of Thr 124 (1, 8, 23, 24, 42–44), or dephosphorylation of Ser 120 and 123 (9–11, 63) was shown to stimulate unwinding. For RPA, it was suggested that hypoxia causes hyperphosphorylation of the p34 subunit, thus inhibiting the single-strand binding activity of RPA which is necessary for replicon initiation (28). Since only minor amounts of these proteins may be actually engaged in SV40 initiation and elongation, such changes may escape detection when the phosphorylation pattern of whole-cell protein is analyzed. This may explain why we found no significant changes in whole-cell T-antigen phosphorylation before and after reoxygenation (21), although their occurrence cannot be excluded so far.

Besides activation of origin unwinding via phosphorylation or dephosphorylation, other possibilities exist. Eucaryotic and viral origins of replication were shown to rely upon binding of transcriptional activators for their function (12, 18, 32). Interaction of AP1 with T antigen was shown to stimulate origin unwinding in polyomavirus (30). Unwinding may also be induced by binding of AP1 or other transcription factors, like NF-κB, to the viral enhancer (39, 40, 45) or to auxiliary sequences flanking the SV40 core origin of replication (31). Activation and increased DNA binding capacity of AP1 and NF-κB have been demonstrated upon hypoxia and reoxygenation (34, 37, 56).

Final conclusions of how SV40 origin unwinding is blocked by hypoxia cannot be drawn at present. Determination of the phosphorylation patterns of T antigen and RPA and identification of the proteins bound to the SV40 minichromosome before and after reoxygenation will help to elucidate the above-mentioned questions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge G. Probst for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (grant Pr95/11-1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamczewski J P, Gannon J V, Hunt T. Simian virus 40 large T antigen associates with cyclin A and p33cdk2. J Virol. 1993;67:6551–6557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6551-6557.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowiec J A, Hurwitz J. ATP stimulates the binding of simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen to the SV40 origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:64–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borowiec J A, Hurwitz J. Localized melting and structural changes in the SV40 origin of DNA replication induced by T-antigen. EMBO J. 1988;7:3149–3158. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowiec J A, Dean F B, Bullock P A, Hurwitz J. Binding and unwinding—how T antigen engages the SV40 origin of DNA replication. Cell. 1990;60:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90730-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brischwein K, Engelcke M, Riedinger H-J, Probst H. Role of ribonucleotide reductase and deoxynucleotide pools in the oxygen-dependent control of DNA replication in Ehrlich ascites cells. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullock P A. The initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:503–568. doi: 10.3109/10409239709082001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullock P A, Seo Y S, Hurwitz J. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro: pulse-chase experiments identify the first labeled species as topologically unwound. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3944–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannella D, Roberts J M, Fotedar R. Association of cyclin A and cdk2 with SV40 DNA in replication initiation complexes is cell cycle dependent. Chromosoma. 1997;105:349–359. doi: 10.1007/BF02529750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cegielska A, Virshup D M. Control of simian virus 40 DNA replication by the HeLa cell nuclear kinase casein kinase I. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1202–1211. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cegielska A, Moarefi I, Fanning E, Virshup D M. T-antigen kinase inhibits simian virus 40 DNA replication by phosphorylation of intact T antigen on serines 120 and 123. J Virol. 1994;68:269–275. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.269-275.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cegielska A, Shaffer S, Derua R, Goris J, Virshup D M. Different oligomeric forms of protein phosphatase 2A activate and inhibit simian virus 40 DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4616–4623. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng L, Kelly T J. Transcriptional activator nuclear factor I stimulates the replication of SV40 minichromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Cell. 1989;59:541–551. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins K L, Kelly T J. The effects of T antigen and replication protein A on the initiation of DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase α-primase. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2108–2115. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean F, Borowiec J A, Eki T, Hurwitz J. The simian virus 40 T antigen double hexamer assembles around the DNA at the replication origin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14129–14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean F B, Dodson M, Echols H, Hurwitz J. ATP-dependent formation of a specialized nucleoprotein structure by simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen at the SV40 replication origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8981–8985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dean F B, Bullock P, Murakami Y, Wobbe C R, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. Simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA replication: SV40 large T antigen unwinds DNA containing the SV40 origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:16–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deb S P, Tegtmeyer P. ATP enhances the binding of simian virus 40 large T antigen to the origin of replication. J Virol. 1987;61:3649–3654. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3649-3654.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DePamphilis M L. How transcription factors regulate origins of DNA replication in eukaroytic cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1993;3:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90137-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diddens H, Gekeler V, Neumann M, Niethammer D. Characterization of actinomycin-D-resistant CHO cell lines exhibiting a multidrug-resistance phenotype and amplified DNA sequences. Int J Cancer. 1987;40:635–642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dornreiter K, Erdile L F, Gilbert I U, von Winkler D, Kelly T J, Fanning E. Interaction of DNA polymerase α-primase with cellular replication protein A and SV40 T antigen. EMBO J. 1992;11:769–776. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreier T, Scheidtmann K H, Probst H. Synchronous replication of SV 40 DNA in virus infected TC 7 cells induced by transient hypoxia. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80853-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dröge P, Sogo J, Stahl H. Inhibition of DNA synthesis by aphidicolin induces supercoiling in simian virus 40 replicative intermediates. EMBO J. 1985;5:3241–3246. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fanning E. Simian virus 40 large T antigen: the puzzle, the pieces, and the emerging picture. J Virol. 1992;66:1289–1293. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1289-1293.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fanning E. Control of SV40 DNA replication by protein phosphorylation: a model for cellular DNA replication? Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:250–255. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farmer G, Bargonetti J, Zhu H, Friedman P, Prywes R, Prives C. Wild-type p53 activates transcription in vitro. Nature. 1992;358:83–86. doi: 10.1038/358083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gannon J V, Lane D P. Interactions between SV40 T antigen and DNA polymerase α. New Biol. 1990;2:84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gekeler V, Epple J, Kleymann G, Probst H. Selective and synchronous activation of early-S-phase replicons of Ehrlich ascites cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5020–5033. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giaccia A J. Hypoxic stress proteins: survival of the fittest. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1996;6:46–58. doi: 10.1053/SRAO0060046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray H B, Jr, Winston T P, Hodnett J L, Legerski R J, Nees D W, Wie C F, Robberson D L. The extracellular nuclease from Alteromonas espejiana: an enzyme highly specific for nonduplex structure in nominally duplex DNAs. In: Chirikjian J G, Papas T S, editors. Gene amplification and analysis: structural analysis of nucleic acids. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Biomedical Press; 1981. pp. 169–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo W, Tang W J, Bu X, Bermudez V, Martin M, Folk W R. AP1 enhances polyomavirus DNA replication by promoting T-antigen-mediated unwinding of DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:4914–4918. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4914-4918.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutierrez C, Guo Z-G, Roberts J, DePamphilis M L. Simian virus 40 origin auxiliary sequences weakly facilitate T-antigen binding but strongly facilitate DNA unwinding. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1719–1728. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinz N H. Transcription factors and the control of DNA replication. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:459–467. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iftode C, Borowiec J A. Denaturation of the simian virus 40 origin of replication mediated by human replication protein A. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3876–3883. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imbert V, Rupec R A, Livolsi A, Pahl H L, Traenckner E B-M, Mueller-Dieckmann C, Farahifar D, Rossi B, Auberger P, Baeuerle P A, Peyron J-F. Tyrosine phosphorylation of IκB-α activates NF-κB without proteolytic degradation of IκB-α. Cell. 1996;86:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jay G, Khy G, DeLeo A B, Dippold W G, Old L J. p53 transformation-related protein: detection of an associated phosphotransferase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2932–2936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhar S G, Lehman J M. T antigen and p53 in pre- and post-crisis simian virus 40-transformed human cell lines. Oncogene. 1991;6:1499–1506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laderoute K R, Webster K A. Hypoxia/reoxygenation stimulates Jun kinase activity through redox signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1997;80:336–344. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lilley D M, Hallam L R. Thermodynamics of the ColE1 cruciform. Comparisons between probing and topological experiments using single topoisomers. J Mol Biol. 1984;180:179–200. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macchi M, Bornert J M, Davidson I, Kanno M, Rosales R, Vigneron M, Xiao J H, Fromental C, Chambon P. The SV40 TC-II (κB) enhanson binds ubiquitous and cell type specifically inducible nuclear proteins from lymphoid and non-lymphoid cell lines. EMBO J. 1989;8:4215–4227. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin M, Piette J, Yaniv M, Tang W J, Folk W R. Activation of polyomavirus enhancer by a murine activator protein 1 (AP1) homolog and two contiguous proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5839–5843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mastrangelo I A, Hough P V C, Wall J S, Dodson M, Dean F B, Hurwitz J. ATP-dependent assembly of double hexamers of SV40 T antigen at the viral origin of DNA replication. Nature (London) 1989;338:658–662. doi: 10.1038/338658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McVey D, Brizuela L, Mohr I, Marshak D R, Gluzman Y. Phosphorylation of large tumor virus antigen by cdc2 stimulates SV40 DNA replication. Nature (London) 1989;341:503–507. doi: 10.1038/341503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McVey D, Ray S, Gluzman Y, Berger L, Wildeman A G, Marshak D R, Tegtmeyer P. cdc2 phosphorylation of threonine 124 activates the origin-unwinding functions of simian virus 40 T antigen. J Virol. 1993;67:5206–5215. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5206-5215.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moarefi I F, Small D, Gilbert I, Höpfner M, Randall S K, Schneider C, Russo A A R, Ramsperger U, Arthur A K, Stahl H, Kelly T J, Fanning E. Mutation of the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation site in simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen specifically blocks SV40 origin DNA unwinding. J Virol. 1993;67:4992–5002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4992-5002.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakamura M, Niki M, Ohtani K, Saito S, Hinumo Y, Sugamura K. Cell line-dependent response of the enhancer element of simian virus 40 to transactivator p40tax encoded by human T-cell leukemia virus type I. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20189–20192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nethanel T, Kaufmann G. Two DNA polymerases may be required for synthesis of the lagging DNA-strand of simian virus 40. J Virol. 1990;64:5912–5918. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.5912-5918.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nethanel T, Reisfeld S, Dinter-Gottlieb G, Kaufmann G. An Okazaki piece of simian virus 40 may be synthesized by ligation of shorter precursor chains. J Virol. 1988;62:2687–2873. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2867-2873.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parsons R, Anderson M E, Tegtmeyer P. Three domains in the simian virus 40 core origin orchestrate the binding, melting, and DNA helicase activities of T antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:509–518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.509-518.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Probst H, Gekeler V. Reversible inhibition of replicon initiation in Ehrlich ascites cells by anaerobiosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;94:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(80)80186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Probst H, Gekeler V. Oxygen dependent regulation of DNA replication of Ehrlich ascites cells in vitro and in vivo. In: Acker H, editor. Oxygen sensing in tissues. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag, KG; 1988. pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Probst H, Hamprecht K, Gekeler V. Replicon initiation frequency and intracellular levels of ATP, ADP, AMP and of diadenosine 5′,5′′′-P1, P4-tetraphosphate in Ehrlich ascites cells cultured aerobically and anaerobically. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;110:688–693. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Probst H, Schiffer H, Gekeler V, Kienzle-Pfeilsticker H, Stropp U, Stötzer K-E, Frenzel-Stötzer I. Oxygen dependent regulation of DNA synthesis and growth of Ehrlich ascites cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2053–2060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Probst H, Hofstaetter T, Jenke H-S, Gentner P R, Müller-Scholz D. Metabolism and non-random occurrence of nonnascent short chains in the DNA of Ehrlich ascites cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;740:200–211. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(83)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Probst H, Gekeler V, Helftenbein E. Oxygen dependence of nuclear DNA replication in Ehrlich ascites cells. Exp Cell Res. 1984;154:327–341. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(84)90157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts J M. Simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen causes stepwise changes in SV40 origin structure during initiation of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3939–3943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rupec R A, Baeuerle P A. The genomic response of tumor cells to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Differential activation of transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:632–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.632_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stahl H, Knippers R. Simian virus 40 large tumor antigen on replicating viral chromatin: tight binding and localization on the viral genome. J Virol. 1983;47:65–76. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.1.65-76.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stillman B W, Gluzman Y. Replication and supercoiling of simian virus 40 DNA in cell extracts from human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2051–2060. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsurimoto T, Stillman B. Replication factors required for SV40 DNA replication in vitro. I. DNA structure-specific recognition of a primer-template junction by eukaryotic DNA polymerases and their accessory proteins. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1950–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsurimoto T, Stillman B. Replication factors required for SV40 DNA replication in vitro. II. Switching of DNA polymerase α and δ during initiation of leading and lagging strand synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1961–1968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsurimoto T, Fairman M P, Stillman B. Simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro: identification of multiple stages of initiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3839–3849. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Virshup D M, Russo A A, Kelly T J. Mechanism of activation of simian virus 40 DNA replication by protein phosphatase 2A. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4883–4895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wobbe C R, Dean F, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. In vitro replication of duplex circular DNA containing the simian virus 40 DNA origin site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5710–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wold M S, Kelly T J. Purification and characterization of replication protein A, a cellular protein required for in vitro replication of simian virus 40 DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2523–2527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wold M S, Li J J, Kelly T J. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro: large-tumor-antigen- and origin-dependent unwinding of the template. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3643–3647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]