Abstract

Idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis (IUL) is characterized by bilateral ulceration of vocal cords which is followed by a protracted course of healing. It is rarely diagnosed, with a paucity of published data in English literature. There is no published data on this topic in the Indian population. Twenty-one patients from 3 centres were prospectively evaluated for clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. All patients underwent fibreoptic laryngoscopic evaluation and stroboscopic assessment. They were treated with supportive care and stringent follow-up. 21 patients with a median age of 39 years were included. This condition was commonly seen in males. All patients were treated conservatively except two who underwent a biopsy. The average time for full recovery in 14 of our patients who had compliant follow-ups was 9.24 weeks. GRBAS score improved from 9 to 5.93(p < 0.0001). Self-reported voice outcomes improved in all patients except for one patient who had a biopsy. IUL is uncommon but not rare in the Indian population. It shows full recovery with conservative management that involves at least more than 3–4 weeks.

Keywords: Idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis, Prolonged ulcerative laryngitis, Vocal cords ulcerations, Acute laryngitis

Introduction

Idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis (IUL) is an uncommon disease that is characterized by hoarseness and mid-membranous ulceration of both vocal cords. This is often preceded by a history of cough for days or weeks. It was first described by Spigel in 2000 and was described as ‘prolonged ulcerative laryngitis’ [1]. It carries a protracted course with hoarseness and ulcerative lesions taking weeks to heal and sometimes with sequelae. Treatment is not well established as there is limited evidence on the treatment of this condition. There is a paucity of data with less than ten research articles published in English literature [2–8] and to our knowledge none from India or the Indian subcontinent.

As there is limited knowledge on the aetiology, treatment, or long-term sequelae of this disease, there is a wide discrepancy in how this disease is treated. Researchers have used antifungal and antibacterial medications while some have elected to treat this entity by biopsy of the ulcer. Although we know that disease exists there is a need to establish a consensus on the aetiology and treatment and course of this condition.

The study aims to explore and share our experience in treating 21 cases of ulcerative laryngitis with long-term follow-up and to understand the course of the disease. To our knowledge, this is the first such study on the Indian population.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective study of 21 patients who were diagnosed with idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis over 6 years period (2016 to 2022). After ethical committee approval, patients attending the ENT outpatient clinic (2 hospitals and 1 clinic) were enrolled. A detailed history regarding onset, duration, progression, comorbidity, and any predisposing factors was recorded. Further, patients underwent stroboscopic examination with Ecleris Stroboscope (Ecleris, Medley, FL) using a 700 Hopkins telescope or a flexible laryngoscopic examination using a Pentax laryngoscope. (Japan).

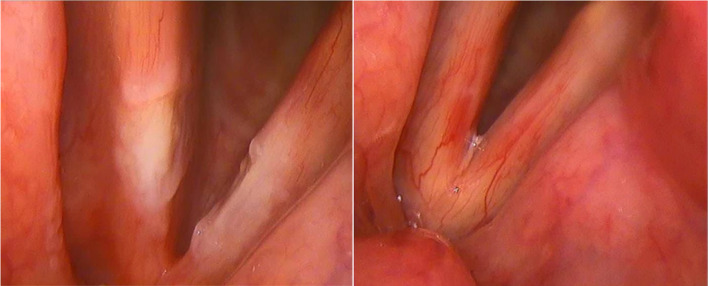

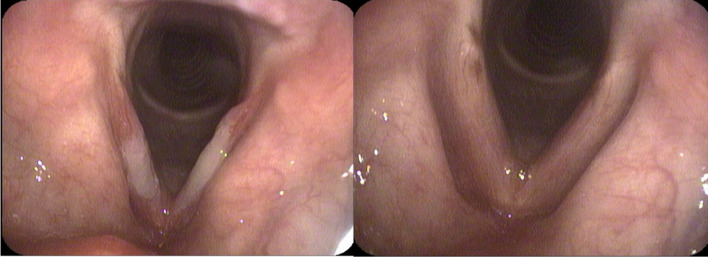

Patients were included in the study if they were preceded by a viral infection and endoscopy showed findings suggestive of ulceration and hyperemia on the mid-membranous cords. The stroboscopic image of IUL is shown in Fig. 1 while a flexible laryngoscopic finding is shown in Fig. 2 respectively.

Fig. 1.

IUL at presentation (4 weeks from onset of symptoms) and after 4 weeks of treatment on rigid stroboscopic examination

Fig. 2.

IUL at 2 weeks of presentation and following 6 weeks of treatment on flexible laryngoscopy

Patients with any specific infections (for example TB, Sarcoid etc.) or any systemic inflammatory disease (connective tissue disorders) were excluded. All the patients underwent a chest x-ray to exclude any lung pathology.

They were all treated conservatively with supportive measures (PPIs, voice rest, and occasionally antifungal medication). Two patients underwent a biopsy as one was a smoker and the other did not respond to conservative treatment for 6 weeks. Patients were followed up regularly till complete recovery and for a further few weeks. During this time, they were assessed for improvement in patient-related vocal outcomes, perceptive voice assessment using the GRBAS scale and morphologic sequelae with follow-up stroboscopy. All the findings were recorded on an excel sheet. Statistical evaluation of voice performance at presentation and end of treatment or follow-up were compared using student t-test.

Results

21 patients were studied, the details of which are described. There were 6 females and 15 males in our study. The median age was 39 years with the youngest being 22 years and the oldest being 69 years old. All patients presented with hoarseness with a mean duration of 3 weeks. All patients had a history of cough preceding the hoarseness. 14(65%) of our patients did not give a history of vocal abuse, while 7(35%) of them had a positive history of overuse of voice. All of them were evaluated with rigid stroboscopy and flexible laryngoscopy. Ulcerative lesions were identified in all these patients. All of our patients received proton pump inhibitors and were advised limited voice use for a period of 3 to 4 weeks. Two patients received antifungals since they were taking steroid inhalers and the lesions were misinterpreted to be fungal laryngitis. Two patients underwent a biopsy as one was a smoker, and the other had a protracted course. In both cases, the histopathology was negative for malignancy and only showed an inflammatory reaction.

All of our patients were asked to come for a follow-up after 3 weeks of therapy. 3 of our patients were completely lost for follow up while the follow-up period of the other 18 of our patients ranged from 2 to 30 weeks. Of these, another 3 had a short follow-up of 2–3 weeks and they were lost for follow-up before the lesions healed, thereby making it difficult to assess whether they fully recovered or not. Hence, they were excluded from further study. Of the 15 patients who had a complete follow-up, the mean presenting GRBAS score was found to be 9.

The average time to recover in the remaining 15 patients ranged from 6 to 16 weeks from the onset of symptoms with an average of 9.24 weeks. The mean GRBAS score at their final follow-up was 3.07 and the mean difference between pre-treatment and post-treatment GRBAS was 5.93 (95% CI of 5.45 to 6.41). Paired t-test was done to evaluate the significance and the p-value was found to be 0.0001 showing significant improvement after treatment. Clinically all patients reported complete recovery of their voice except one of the patients who underwent a biopsy. This patient had some difficulty with his singing voice while having a normal speaking voice. His stroboscopic examination showed a decrease in the amplitude of mucosal waves.

Discussion

IUL is a rare disease of unknown aetiology characterized by persistent dysphonia, cough, and bilateral ulcerations in the mid-membranous portions of the vocal cords. The condition is preceded by acute viral laryngitis which later develops into mid-membranous ulcerations over the vocal cords that heal over a prolonged course [2]. It is rarely diagnosed probably due to a lack of awareness rather than the disease being rare. In a study by Kim et al. which interviewed around 100 academic laryngologists, at least 20% of the respondents reported that they have seen more than 20 cases of IUL [3]. Most papers report a predominance of females contracting this disease, however, 75% of our patients were males.

The aetiology of this condition seems to be uncertain. A biopsy is rarely done as this may lead to scar formation and a non-pliable vocal cord [2]. A biopsy done by Rakel et al. showed an inflammatory reaction with no cellular atypia [4]. Similar findings were seen in two of our patients who underwent a biopsy. Further, a small number of patients were cultured for bacterial, viral, and fungal aetiologies in Rakel’s series, but a causative organism was not found in any of these. We presumed the causative organism to be fungal in the first 2 patients as they were using steroid inhalers for their cough, and we continued treatment with antifungals and supportive care. The cohort of patients who were treated later without antifungals showed complete recovery without antifungals, thereby questioning the need for antifungal medications.

A cough seems to be the commonest denominator in all these cases and has become one of the criteria for its diagnosis. However, protracted cough as the aetiology of ulcers is questionable as coughing is closely associated with posterior vocal fold trauma, leading to ulcerations and granulomas over the vocal process and not over the mid-membranous cords. Similarly, laryngopharyngeal reflux is also associated with posterior glottic lesions rather than in the mid-membranous region and cannot be considered an aetiological factor. All our patients had a history of cough before developing ulceration over the vocal cords.

Since there is no defined aetiology, there are no clear treatment guidelines. Most academic laryngologists interviewed in Kim’s series treated their patients with absolute or modified voice rest for 3–4 weeks, proton pump inhibitors and oral steroids [3]. Reetz et al. treated their patients with an inhalational solution consisting of panthenol and saline for 4–6 weeks with steroids added in the first week [5]. Our patients received PPIs for 6 weeks and were advised limited voice use for 3–4 weeks. Voice rest either absolute or modified appears to be prudent as the ulcers are in the striking zone of the vocal cords. Steroids are presumably given by some authors to prevent scar formation. However, none of our patients were given oral or topical steroids and we believe that this may not be required as all of our patients recovered completely except for one [who developed scar post-biopsy).

All studies have described the prolonged course of the disease with the average healing time of ulcers being 2 to 4 months [2, 6, 7]. Nine weeks was the average duration taken for the ulcers to heal in our study and it ranged from 5 to 16 weeks from the onset of symptoms. It is important to educate the patients regarding the prolonged nature of the disease and the need for long-term follow-up in comparison to a commonly occurring acute laryngitis. Any patients with persistent voice change following acute laryngitis should be followed up for possible development of IUL. Follow-up in India is problematic with patients changing doctors seeking an immediate cure. This is also reflected in our series with 3 (15%) of our patients who did not have a single follow-up and another 3 (15%) visited only once and were then lost for follow-up. It is pertinent that both patients, as well as the clinician, should exert patience during this treatment and resist temptations to intervene with biopsy thereby giving adequate time for the ulcers to heal.

There is debate in the literature regarding the sequelae of the disease with some studies reporting no permanent sequelae (Reetz et al. [5] and Hsiao [6]), whilst others reporting permanent sequelae following complete resolution of ulcers. In Kim’s series, vocal cord stiffness and dysphonia were considered permanent sequelae by 89.6 and 81.3% of the respondents [3] respectively. Simpson et al. reported persistent vibratory abnormalities after complete resolution of ulcers in as many as 60% of the patients [2]. Sinclair also described a granuloma developing over the healed ulcer but saw full resolution with conservative management [8]. Young et al. who studied in detail the voice and stroboscopic outcomes of 23 patients believe younger age, shorter duration of symptoms and antireflux treatment were significant predictors of voice outcome. We did not see any permanent sequelae in any of our patients except one patient who had undergone a biopsy. All others showed good resolution of ulcers as well as improved voice performance throughout the disease without any long-term sequelae. The detailed analysis of treatment and sequelae by different authors has been presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature review of IUL over the years with treatment, Followup and sequelae

| Authors | Treatment | Time to heal | Sequelae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rakel et al. [4] | Oral steroids, antibiotics, PPI, voice rest, voice therapy, biopsy (2/14) | Upto 1 year | |

| Hsiao [6] | Observation, non-specific therapy | 9.4 weeks (4 to 20 weeks) | None |

| Simpson et al. [2] | Antifungals: 14 (93%), PPI 13 (87%), steroids po:4 (27%), antibiotics 2 (13%) | 2 to 10 months | 60% mucosal wave abnormalities |

| Young et al. [7] | PPI: 85%, antibiotics 22%, steroids 52%, antivirals 52%, antimycotics 39%, voice rest 65% | 2.25 months | Decreased mucosal wave vibrations |

| Reetz et al. [5] | An inhalational solution containing Panthenol and saline for 4–6 weeks with added steroids in the first week | 3–6 months | None |

| Present series | PPI’s for 6 weeks; Limited voice use for 3–4 weeks | 9 weeks (5 to 16 weeks) | None except one who underwent a biopsy |

Conclusion

IUL is an uncommon disease but not rare. With the current literature available, treatment of this condition should include absolute or modified voice rest and PPIs. Antibacterials and antifungals have no role and biopsy should be avoided unless there is a strong suspicion of malignancy. Patience is the key while treating this condition as the disease takes a prolonged course and complete resolution may take 2–4 months.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the AOI National conference 2023, Jaipur.

Appendix 1

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical Approval

Approval taken.

Informed Consent

Attached below as Appendix 1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. K. Manjunath, Email: drmanjumk@gmail.com

Ravi Sachidananda, entravi@googlemail.com.

T. M. Sreenivasa Murthy, Email: tmsreemurthy@gmail.com

R. Jyothi Swarup, Email: drswarup@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Spiegel JR, Sataloff RT, Hawkshaw MJ. Prolonged ulcerative laryngitis. Ear Nose Throat. 2000;79(5):342. doi: 10.1177/014556130007900503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson CB, Sulica L, Postma GN, Rosen CA, Amin MR, Merati AL, Courey MS, Patel V, Johns MM., 3rd Idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(5):1023–1026. doi: 10.1002/lary.21659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim C, Badash I, Gao WZ, O'Dell K, Johns MM., 3rd Idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis: a national survey of academic laryngologists. J Voice. 2021;35(6):892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rakel B, Spiegel JR, Sataloff RT. Prolonged ulcerative laryngitis. J Voice. 2002;16(3):433–438. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reetz S, Brockmann-Bauser M, Bohlender JE. Prolongierte ulzerierende laryngitis [Prolonged ulcerative laryngitis] HNO German. 2022;70(1):14–18. doi: 10.1007/s00106-021-01079-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsiao TY. Prolonged ulcerative laryngitis: a new disease entity. J Voice. 2011;25(2):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young VN, Gartner-Schmidt JL, Enver N, Rothenberger SD, Rosen CA. Characteristics and voice outcomes of ulcerative laryngitis. J Voice. 2020;34(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinclair CF, Sulica L. Idiopathic ulcerative laryngitis causing midmembranous vocal fold granuloma. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(2):458–459. doi: 10.1002/lary.23520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]