Abstract

To study the causes of the Pseudo- Lyre sign which is radiologically demonstrated in tumours other than the carotid body tumour. The study is based on an unusual case of neurofibroma of the cervical sympathetic chain presenting as a pulsatile mass in the carotid triangle in a 34 years female. Radiological investigation pointed to a diagnosis of a carotid body tumour because of typical splaying of the internal and external arteries causing the Lyre sign. At surgery, the tumour which was arising from the cervical sympathetic chain (CSC) was excised with minimum blood loss and histopathology confirmed it to be neurofibroma. This, we presume is the first ever report of a neurofibroma of the cervical sympathetic chain causing Lyre sign which we have referred to as Pseudo-Lyre sign. The various investigations which help in diagnosing the cause of Pseudo-Lyre sign have been discussed. All tumours causing Lyre sign on radio-imaging are not carotid body tumours. Other masses mostly neurogenic can demonstrate this sign and an attempt should be made preoperatively to confirm the diagnosis.

Keywords: Lyre sign, Neurofibroma, Cervical sympathetic chain, Horner's syndrome

Introduction

Lyre sign refers to the splaying of the external and internal and external carotid arteries, classically seen on angiography in carotid body tumours or chemodectomas which arise from the carotid bifurcation in the glomus cells derived from the neural crest. Rarely other tumours which develop near the carotid bifurcation like neurogenic tumours or paragangliomas of the vagus nerve and cervical sympathetic chain have been reported to mimic the radiological appearance of carotid body tumour and In that case it is referred to as Pseudo-Lyre sign [1]. Among the neurogenic tumours, both schwannomas and neurofibromas of the vagus and the cervical sympathetic chain have been reported. While splaying of the internal and external carotid arteries has been described with schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain, its association with a neurofibroma of the cervical sympathetic chain has not been reported so far. We are reporting the first ever case of a Pseudo-Lyre sign caused by a neurofibroma arising from the cervical sympathetic chain.

Case Report

A 34-years-old normotensive, euthyroid female with no past medical history presented with a painless swelling in the right upper lateral neck for 2 years which was progressively increasing in size. There was no history of cough, dysphonia, dysphagia, odynophagia, syncopal attack/giddiness, associated pain, palpitations or respiratory distress. No caif-au-lait spots or any neurofibroma was seen on the skin. There was no neurological deficit. Examination showed an approximately 2 × 3 cm pulsatile, nontender swelling located in the right carotid triangle, firm in consistency, mobile in horizontal direction only (Fontaine sign) with no overlying skin changes. No cervical lymphadenopathy was noted. No bruit could be heard over the tumour. Rest of the ear, nose and throat examination was insignificant. Her BP was 124/88 and pulse rate was 84 bpm. In view of the pulsatile nature of the mass present at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery in a female patient in the fourth decade of life, a clinical diagnosis of a carotid body tumour was made with a differential diagnosis of a neurogenic tumour. All blood investigations were done including VMA and VMA/creatinine ratio which were reported to be normal. USG neck showed a well-defined, circumscribed, hypoechoic, oval lesion measuring 19 × 22 mm in size along the course of right vagus nerve with evidence of tailing near bifurcation of right common carotid artery causing anterior displacement and splaying of right Internal carotid artery (ICA) and external carotid artery (ECA). Internal vascularity was noted and these features were suggestive of right vagal schwannoma. CT angiography of the neck (Fig. 1) showed a well-defined oval 29 × 20 × 22 mm mass lesion,arising from the bifurcation of the right common carotid artery (CCA), causing splaying of ICA and ECA suggestive of carotid body paraganglioma with a possibility of vagal schwannoma. FNAC was inconclusive.

Fig. 1.

CT Angigraph showing the Lyre’s sign. Inset: The Lyre

The informed consent of the patient for surgery was taken after explaining about the possibility of injury to the involved nerve and vascular structures with their consequences. The surgery was conducted under general anaesthesia. Using the transverse cervical approach, the carotid sheath was identified and was carefully incised to reveal a well encapsulated tumour about 3 × 2 cm arising from the right cervical sympathetic chain and causing splaying of the external and internal carotid arteries (Fig. 2). The internal jugular vein was laterally displaced and the vagus nerve was intact and normal in course. The mass was separated meticulously from the right ICA and ECA. The vagus, hypoglossal and accessory nerves were preserved (Fig. 3). There was no vascular injury and minimal blood loss. The tumour which was arising from the cervical sympathetic chain could not be isolated from the nerve which had to be sacrificed for complete tumour removal (Fig. 4) Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of neurofiboma. Postoperatively, the patient had ptosis and miosis on the right side which suggested development of right Horner's syndrome (Fig. 5). However, there was no evidence of anhidrosis and enophthalmos.

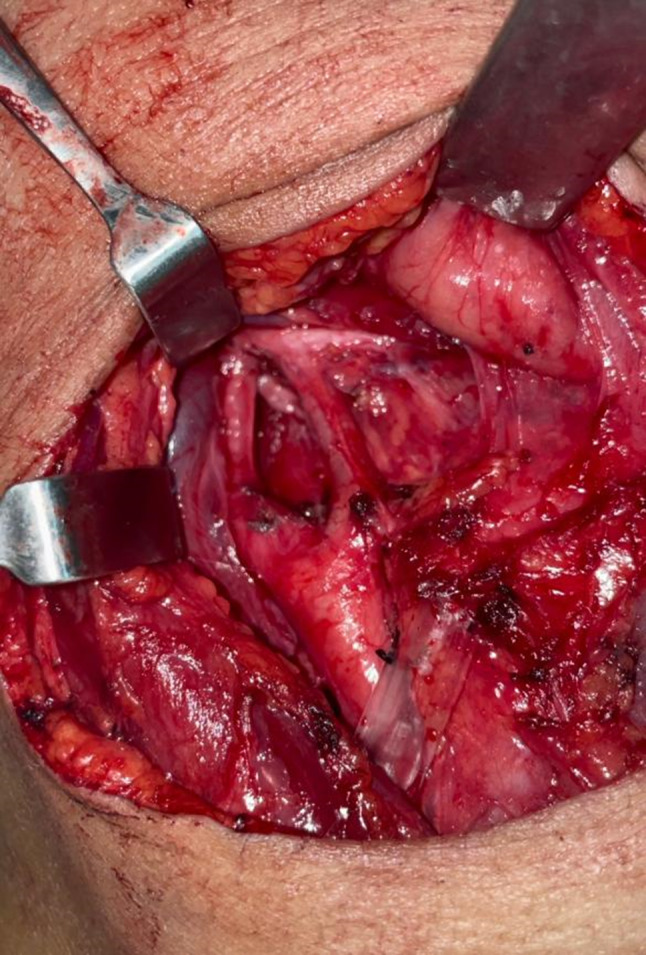

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative view of the tumour splaying the ECA and ICA

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative view after tumour removal

Fig. 4.

The tumour after removal. The nerve (CSC) exiting the tumour (arrow)

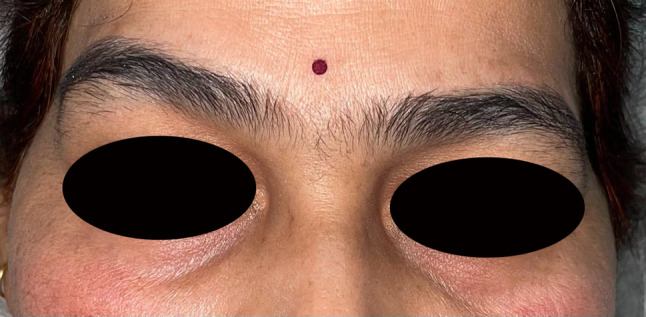

Fig. 5.

Post-operative photograph of the patient showing right-sided miosis and mild ptosis (Horner’s syndrome)

Discussion

The CCA bifurcates at a sharp angle in the neck but if a space-occupying lesion develops at this site, there is splaying of the internal and external carotid arteries and this on radio-imaging has been called the Lyre sign after the musical instrument of that name (Fig. 1, Inset). This sign has classically been described in carotid body tumour which arises from the glomus cells present at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. However, other tumours which develop near the carotid bifurcation have also been reported to demonstrate this sign when it is referred to as the Pseudo-Lyre sign. These include cervical sympathetic chain schwannomas [2–4]; vagal paraganglioma [5]; vagal neurofibroma [6], parathyroid carcinoma [7], schwannoma of hypoglossal nerve [8]; pseudoaneurysm of the carotid artery and metastatic nodes [9]. We are reporting a rare occurrence of a neurofibroma of the cervical sympathetic chain causing a Lyre sign and this to our knowledge is the first ever report in English literature.

In the head and neck region,neurofibromas are much rarer than schwannomas-a ratio of 2:9 has been reported [10]. Symptoms of PNST are based on the size, location, and growth rate of the tumour out of which dysphagia is the most common presenting symptom [6]. Symptoms of the involved nerve like hoarseness or Horner's syndrome may help in differentiating the nerve of origin but only a few patients show paralysis before operation. Our patient developed Horner's syndrome postoperatively. Miosis and ptosis was evident in our patient but anhidrosis and enophthalmos was not present. Ptosis occurring in Horner’s syndrome is minor as the cervical sympathetic chain supplies the superior tarsal muscle whereas ptosis of greater extent is caused by the paralysis of the oculomotor nerve which supplies the levator palpebrae superioris muscle. Anhidrosis is not usually encountered postoperatively in patients with CSC tumour [11]. Enophthalmos reported in Horner’s syndrome is apparent rather than real. This is due to the small palpebral fissure caused by ptosis which makes the eye look sunken on the affected side but the position of the globe in the orbit remains unchanged. Even the apparent enophthalmos was not seen in our patient because of the minor ptosis. In the present case, the neurofibroma of cervical sympathetic chain presented as a painless mass in the neck without causing any functional impairment. This is the typical presentation of a CSC neurogenic tumour since the CSC runs in a loose facial compartment and is not easily compressed. Peroperatively, the differentiation between a schwannoma and neurofibromas can be made by observing the course of the parent nerve in relation to the tumour. If the parent nerve enters and exits centrally, neurofibroma is the preferred diagnosis as was seen in our case, and if the parent nerve is found to be eccentric schwannoma is more likely. As shown in Fig. 4, the nerve is seen exiting the tumour centrally.

Genesis of Lyre/Pseudo Lyre Sign

The carotid body is located in the adventitia of the CCA at its bifurcation. When a tumour arises from the carotid body, it widens the narrow space between the ICA and ECA causing splaying of the vessels and producing the classical Lyre sign on angiography. The CSC, at the level of the carotid bifurcation lies just posteromedial to the ICA on the prevertebral fascia or within the carotid sheath. Because of limitation of the cervical vertebral column medially and longus capitis muscle posteriorly, a tumour arising from the CSC can possibly grow into the space between the ICA and ECA [3], thus producing the Pseudo-Lyre sign on angiography. This situation is more likely to occur when the CSC lies within the carotid sheath as happens in a small percentage of cases.

Radiological Investigations

Ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and angiography are important modalities for preoperative diagnosis of any cervical tumour. The mass growing posterior to the common carotid artery (CCA) and the ICA will displace the vessels anteriorly or laterally with increase in its size. This holds true for both vagal and cervical sympathetic chain tumours [12]. Both sympathetic chain tumours and vagal tumours can mimic carotid body tumours on imaging studies [6]. Despite the various imaging modalities available, it was difficult to confirm whether the space occupying lesion arose from the carotid vascular system, vagus nerve or cervical sympathetic chain and it remained unclear till we surgically explored the site of lesion. MRI alone is not reliable in distinguishing the vascular characteristics of these tumours as both neurofibromas and carotid body tumours can present as T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense masses. MR angiography can differentiate carotid body tumours and cervical sympathetic chain neurogenic tumour by the appearance of tumour vascularity. However, conventional angiography, an invasive procedure, may still be necessary because some schwannomas have significant vascularity within the tumour or around the capsule [2]. Thus, a possibility of cervical sympathetic chain neurofibroma should be included in the differential diagnosis when radiological studies reveal carotid splaying.

Treatment

Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for neurofibromas since they are relatively radioresistant. In view of the asymptomatic nature of these tumours, watchful waiting could be an option but should be avoided because of the rare possibility of a malignant transformation. In addition, the patients usually are in a younger age group (20–40 years) [13] and with long years ahead, the slowly growing tumour may enlarge sufficiently to produce symptoms. Also, in view of the difficulties in confirmation of diagnosis preoperatively, excision for histopathological diagnosis is required. The diagnosis of peripheral nerve sheath tumours is very important preoperatively as it helps in warning the patient about the postoperative complications like Horner's syndrome as happened in our case or other nerve deficits.

Conclusion

Whenever confronted with a radiological appearance of Lyre sign, it is important to remember that it can be caused by other conditions apart from carotid body tumour especially a neurogenic tumour and all attempts should be made preoperatively to correctly differentiate carotid body tumour from a neurogenic tumour. This is of utmost importance for proper surgical planning and prediction of complications. A high index of suspicion coupled with various investigations like ultrasound, colour Doppler study of neck vessels, CT angiography, MR angiography, FNAC and if in doubt, angiography of neck vessels can help in the correct preoperative diagnosis since neurofibroma of cervical sympathetic chain may not present with any specific symptoms except as a slow growing pulsatile mass in the upper lateral region of the neck. Surgical removal is the treatment of choice and if a correct preoperative diagnosis is made, the surgeon will be under little stress compared to if the surgery is to be performed for a chemodectoma when intervention of the vascular surgeon may be required.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nash R, Farrell R. Pseudo-lyre sign. J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2011(2):2. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2011.2.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang CP, Hsiao JK, KO JY. Splaying of the carotid bifurcation caused by a cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngo. 2004;1:113. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langerman A, Rangarajan SV, Athavale SM, Pham MQ, Sinard RJ, Netterville JL. Tumors of the cervical sympathetic chain-diagnosis and management. Head Neck. 2013;37(7):930–933. doi: 10.1002/hed.23050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil H, Rege S. Horner's syndrome due to cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma: a rare presentation and review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019;14(3):1013–1016. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_58_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh D, Krishna PR. Paraganglioma of the vagus nerve mimicking as a carotid body tumour. J Vascular Surg. 2007;46(1):144. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itawi SA, Buehler M, Mark RE, Mansour TR, Medhkour Y, Medhkour A. A unique case of carotid splaying by a cervical vagal neurofibroma and the role of neuroradiology in surgical management. Cureus. 2017;9(9):e1658. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed W, Kanatas AN, Mitchell DA. Parathyroid carcinoma radiographically mimicking a carotid body tumour. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(6):620–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MK, Siddell DR, Mendelsohn AH, Blackwell KE. Hypoglossal schwannoma masquerading as a carotid body tumour. Case Reports Otolaryngol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/842761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkatanarasimha N, Olubaniyi B, Freeman SJ, Suresh P. Usual and unusual causes of splaying of the carotid artery bifurcation: the lyre sign- a pictorial review. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s10140-010-0907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anil G, Tan TY. CT and MRI evaluation of nerve sheath tumours of the cervical vagus nerve. AJR. 2011;197:195–201. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weipert M, O'Mara S. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. Consultant. 2021;61:e12–e16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibrahim HA, Sepahdari AR. Enhancing mass at the carotid bifurcation: not always a carotid body tumour. Neurographics. 2015;5:88–98. doi: 10.3174/ng.3150118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber AL, Montandon C, Robson CD. Neurogenic tumours of the neck. Radiol Clin N Amer. 2000;38:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]