Abstract

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is characterized by painful, oral mucosal ulcers with wide range of prevalence ranging from 2 to 78%. Etiology of RAS is idiopathic and multifactorial. There are numerous gaps in assessment and management of RAS and the absence of guidelines or a consensus document makes the treatment further difficult. The aim of this document is to provide an Indian expert consensus for management of RAS. Experts from different specialties such as Otorhinolaryngology, Oral Medicine/Dentistry and Internal Medicine from India were invited for face to face and online meetings. After a deliberate discussion of current literature, evidence and clinical practice during advisory meetings, experts developed a consensus for management of RAS. We identify that the prevalence of RAS may lie between 2 and 5%. In defining RAS, we advocate three or more recurrences of aphthous ulcers per year as criterion for RAS. Investigation should include basic hematological (complete blood count) and nutritional (serum vitamin B12, and iron studies) parameters. Primary aim of treatment is to reduce the pain, accelerate ulcer healing, reduce the recurrences and improve the quality of life. In treating RAS, initial choice of medications is determined by pain intensity, number and size of ulcers and previous number of recurrences. Topical and systemic agents can be used in combination for effective relief. In conclusion, this consensus will help physicians and may harmonize effective diagnosis and treatment of RAS.

Keywords: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Aphthous ulcer, India, Corticosteroid, Rebamipide, Amlexanox

Introduction

Aphthous stomatitis (AS) is known to affect variable proportion of population (2 to 66%). In India, one out of two individuals are known to suffer with AS in their lifetime. A 3-months recurrence rate is nearly 50% [1, 2]. Reported prevalence of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) in India varies widely in different studies [3–5]. RAS is associated with multiple trigger factors that may differ as per geographical locations. Stress, nutritional deficiency and unknown causes are identified to be important triggers [6, 7]. Differentiation of RAS from other causes of recurrent stomatitis might require detailed investigation for other systemic and local etiologies.

In management of RAS, primary goals include reducing symptoms, accelerating healing, and preventing the recurrences [1]. For treating RAS, a wide range of topical and systemic medications are available [8]. However, selecting an appropriate medication may be challenging. As the etiology of RAS is mostly multifactorial or idiopathic, there is no agreement on specific treatment approach. The evidence for most treatments is based on observational studies [1]. Despite a common occurrence in routine clinical practice in Indian settings, no specific Indian guideline or Expert Consensus exist which may assist Indian physicians to adequately evaluate and to appropriately treat RAS. Therefore, the Indian experts felt a need to create this consensus providing their expert opinion to define, investigate and treat RAS in routine clinical settings.

Approach to the Consensus

Conceptualized by the first and corresponding authors, a national advisory meeting was conducted to discuss the current evidence and formulate the Indian consensus based on clinical experience. The meeting involved ten expert panel members. These members were from cross specialties such as Otorhinolaryngology, Oral Medicine/Dentistry and Internal Medicine. All experts were having over 10 years of experience in the management of RAS. The panel members have been associated with medical institutions, hospitals or having their own private medical practice. Based on their experience and supportive evidence, the panel discussed and finalized the consensus for the manuscript. In following sections, we provide consensus approach in defining, investigating, treating and preventing RAS.

Consensus 1: Defining RAS

There is no fixed definition of RAS. In defining RAS, characteristics of ulcers and period of recurrence are important factors. Some reports indicate RAS is presence of characteristic painful ulcers with a well-defined erythematous margin, spontaneous healing and recurrence on a variable period [8, 9]. In defining ulcers, a standard criterion is applied that differentiates ulcers as major aphthous ulcers, minor aphthous ulcers and herpetiform ulcers (Table 1) [10]. Though RAS is common in younger ages, we observed it in older ages in our experience. Furthermore, there is no clear definition on what actually counts as a recurrence. Recurrence may occur over few months to few days in patients who had apparently healthy period in between two episodes [11]. In this context, based on our experience, we consider 3 or more episodes of aphthous ulceration in a year should be considered as RAS.

Table 1.

Type of recurrent aphthous stomatitis

| Character | Type of RAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Major | Herpetiform | |

| Peak age of onset | Second decade | First/second decade | Third decade |

| Ulcers numbers | One to five | One to three | Multiple |

| Size | < 10 mm | > 10 mm | 1–2 mm |

| Duration | Few to 14 days | 2 to 4 weeks | Few to 14 days |

| Heal with scarring | No | Yes | No |

| Site | Non-keratinized mucosa especially labial/buccal mucosa. Dorsal and lateral borders of the tongue | Keratinized and non-keratinized mucosa, particularly soft palate | Non-keratinized mucosa but particularly floor of the mouth and ventral surface of the tongue |

Consensus: RAS is defined as shallow-ulcers commonly occurring in the oral cavity or pharynx, either as solitary ulcer or multiple ulcers, that present as painful, round ulcer with a well-defined erythematous halo, heal spontaneously and occur three or more times in a year. Recurrence may not occur at the same site. The standard classification of minor, major and herpetiform types is well-accepted. By age, RAS is not only common in young ages but can occur irrespective of the age.

Consensus 2: Epidemiology of RAS

RAS is a commonly encountered clinical condition. Population prevalence is reported to vary from 2 to 66%. Lifetime prevalence of aphthous stomatitis in Indian population is reported to be 50.3% [2]. In a study from Brazil, Queiroz et al. reported RAS prevalence of 47.2% [6]. A study from China involving university students reported overall RAS prevalence of 23.3% [12]. Comparatively, a study from Malaysia reported the prevalence of 5.7% [13]. From India, multiple studies have reported varying prevalence of RAS (Table 2) [3–5, 14–16]. The reported prevalence may not reflect an actual population prevalence and probably overestimates the prevalence of RAS. Nonetheless, some large sample studies identify prevalence ranging from 1.5 to 21.7% [3, 4, 16]. Our experience suggests, RAS prevalence varies between 2 and 5% only. The prevalence may change from time to time and geographical regions as trigger factors and stressor may differ. Lack of correct definition might lead to difference in reported prevalence.

Table 2.

Studies from India reporting prevalence of RAS

| Author (Year) | Sample size | Population | Reported prevalence of RAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bhatnagar et al. (2013) [3] | 1736 | Oral mucosal lesions | 1.53% |

| Patil et al. (2014) [4] | 3244 | General | 21.7% |

| Rao et al. (2015) [5] | 275 | Students | 78.1% |

| Maheswaran et al. (2015) [14] | 140 | Females | 21.4% |

| Rajmane et al. (2017) [15] | 71,851 | General | 0.1% |

| Kaur et al. (2021) [16] | 4225 | General | 18.93% |

Consensus: Lifetime prevalence of RAS may be overestimated in the literature. It may lie between 2 and 5%. RAS prevalence is lower than single isolated ulcer occurrence.

Consensus 3: Trigger Factors and Etiologies of RAS

For aphthous ulcers, multiple trigger factors are identified. Stress, trauma, nutritional deficiency, various drugs, food hypersensitivity, changes in hormones, etc. can lead to recurrent ulceration [1]. As stated earlier, prevalence may differ by geographical locations as trigger factors also tend to differ. The prevalence of RAS at Brazil reported by Queiroz et al. was 47.2% among the patients who had complaints of oral ulcerations. Major etiology of RAS remained idiopathic (70.3%) and the other causes were traumatic (13.5%), stress (8.8%), and nutritional deficiency (7.3%) [6]. From China, Xu et al., reported nutritional deficiency (78.9%) as most common factors for RAS followed by reduced immune function (56.5%), stress (53.4%) and idiopathic cause (19.3%) [7]. From India, Patil et al. reported stress (54.8%) as a most common factor followed by nutritional deficiency (25%), trauma (16%) and idiopathic causes (4.2%) [4].

Genetics also play a role in RAS pathogenesis. If RAS history is in both parents, the likelihood of it in a child is 90%, whereas it is only 20% when neither parent has RAS [17]. In addition, food allergies, are also often a missed cause for RAS [18, 19]. In our experience, gastroesophageal reflux, lifestyle, and poor oral hygiene are also identified as common triggers for RAS. Besides, unhealthy food habits such as drinking carbonated drinks may also lead to RAS [20, 21].

Consensus: Etiology of RAS is idiopathic and often multifactorial. Genetics, nutritional deficiency, stress, trauma, lifestyle changes, gastric reflux, poor oral hygiene, and food allergy can contribute to development of RAS.

Consensus 4: Investigating for RAS

Assess general history including family history, medical comorbidities, skin or genital ulceration, gastrointestinal disturbances, and drug history. History of autoimmune disorders should be assessed. Evaluate the ulcer thoroughly for frequency, duration, numbers, site, size and shape along with ulcer base and the surrounding tissue.

In general approach to a case of RAS, basic hematological investigations such as hemoglobin, blood counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and in some cases, serum vitamin B12, iron studies, and vitamin D levels may be necessary (Table 3). RAS is a multifactorial disease and therefore, one can find the normal observations of one or more factors. Study from Koybasi et al. reported that only positive family history and vitamin B12 had significant correlation with RAS [22]. Complete blood count provides clues to the diagnosis. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is important indicator of nutritional deficiencies. This simple method can be helpful in peripheries where the facilities of nutritional assessments are lacking. Observing hypersegmented neutrophils in peripheral smear also indicates vitamin B12 deficiency. In a study of 273 RAS patients, Chiang et al. reported anemia, serum iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, and folic acid deficiency, and hyperhomocysteinemia in 20.9%, 20.1%, 4.8%, 2.6%, and 7.7% of patients, respectively [23]. Beside vitamin deficiency, micro-minerals deficiencies are also common cause of RAS. In 48 cases of RAS, Yildirimyan, and colleagues reported zinc deficiency in 34 (70.8%) and zinc plus iron deficiency in 14 (29.2%) cases [24]. A meta-analysis of 19 case-control studies with 1079 cases and 965 controls reported significantly lower zinc level in RAS patients than in healthy controls [25]. In studying other elements, Ozturek et al. reported significantly lower zinc and selenium levels and significantly higher Cu levels in RAS patients than healthy controls [26].

Table 3.

Basic investigations for RAS

| Categories | Investigations |

|---|---|

| Hematological |

Complete blood count Blood peripheral smear Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| Nutritional assessments |

Iron studies Serum vitamin B12 levels Serum vitamin D3 levels |

Detailed investigation is necessary when certain red-flag signs manifest (Table 4). These include frequent recurrences (in weeks or every month), non-characteristic ulcer, necrotic ulcer base, non-healing or longer time to heal, presence of local immune deficiency, mixed ulcers, or any other signs in oral cavity that increases clinical suspicion of systemic disease. Pain to acidic fluids is a characteristic of RAS. This can serve as simple screening test in case of non-characteristic ulcers. Biopsy of the ulcer may be necessary in such cases to determine the etiology. If etiology is not determined, flexible GI endoscopy may be opted. Autoimmune disorders are known to be associated with oral ulceration. In evaluating 355 RAS patients, Chiang et al. observed 13.0% patients with serum gastric parietal cell antibody, 19.4% with thyroglobulin antibody and 19.7% with thyroid microsomal antibody [23].

Table 4.

Red-flag signs for detailed investigations of RAS

| Category | Red-flag Signs |

|---|---|

| History |

Concomitant genital/skin ulcers Systemic signs suggestive of autoimmune disorders Drug / food allergy |

| Ulcer related |

Frequent recurrences (in weeks or every month) Non-healing or longer time for healing (> 6 weeks) Necrotic ulcer base Irregular ulcer margin (non-characteristic ulcer) Mixed ulcers Ulcers on keratinized mucosa |

Consensus: Appropriate history, systemic examination and detailed assessment of ulcers along with complete blood count, iron studies, serum vitamin B12, serum vitamin D3 and zinc levels (where available) should suffice in the majority of RAS cases. Detailed investigations with or without biopsy are necessary in presence of red-flag signs.

Consensus 5: Differential Diagnosis of RAS

Table 5 provides the common, less common and rare differentials for RAS. Traumatic ulcers, nutritional deficiency, viral ulcers and ulcers due to drug hypersensitivity are common. As discussed in the etiological aspects, these factors are common differential for RAS. Detailed assessment is necessary for less common and rarer differentials.

Table 5.

Differential diagnosis of RAS

| Common |

|---|

| Traumatic Ulcer (Dental / Hard Bristle Tooth Brush) |

| Drugs (Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral contraceptives, etc.) |

| Nutritional deficiency (iron, folate, zinc, vitamins such as B1, B2, B6, B12, and D3) |

| Viral ulcers (Coxsackie, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Human immunodeficiency virus) |

| Oral Mucositis (post-radiotherapy / chemotherapy) |

| Less Common |

| Dermatological conditions (Pemphigus vulgaris, erythema multiforme, drug-induced bullous pemphigoid, Steven Johnson Syndrome, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) |

| Hormonal disturbances (Addison’s disease, Hypo/Hyperthyroidism, Diabetes) |

| Autoimmune Disorders (Behcet’s Syndrome) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Rare |

| Bacterial infections (Tuberculosis, syphilis) |

| Fever syndromes (Cyclic neutropenia, PFAPA (Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis) syndrome, Sweet syndrome, Familial Mediterranean fever, hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome (HiDS)) |

Consensus: Common diagnosis for RAS can be easily identified in routine clinical examination. For less common and rarer causes, detailed assessment and investigations may be necessary.

Consensus 6: Treatment of RAS

Main aims of treatment of RAS include pain relief, reduction in ulcer size and numbers, reduction in ulcer recurrences and improving the quality of life. The treatment of RAS is determined by disease severity, clinical history, frequency of recurrences and patient tolerability [1]. In general, it is advised to avoid hard food, chocolates, acidic beverages, acidic, salty or spicy food and alcoholic or carbonated beverages. Avoid dental products containing sodium lauryl sulphate as it reduces the healing period and pain [27].

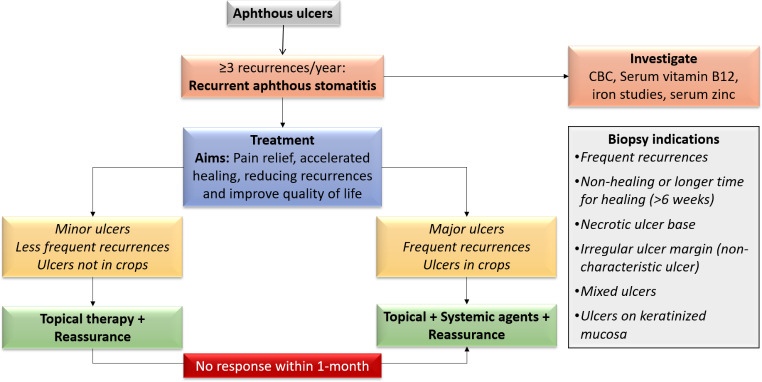

Multiple topical and systemic treatments are available for managing RAS [8]. Table 6 enlists the currently used treatments. Topical treatments are the first line of treatment. Systemic treatments may be necessary in severe disease or when topical treatments do not show positive response. Approach to the treatment of a patient with RAS is depicted in Fig. 1.

Table 6.

Treatments options for RAS

| Category | Treatments |

|---|---|

| Topical/local |

Antiseptics, Anti-inflammatory and analgesics (e.g., 0.2% Chlorhexidine, Amlexanox) Topical antibiotics (e.g., Metronidazole) Topical corticosteroids Topical anaesthetics Other topical treatments: hyaluronic acid |

| Systemic |

Systemic corticosteroids Nutritional supplements Immunomodulators: Levamisole Rebamipide Other: Colchicine, Dapsone, Clofazimine, Carotenoids |

Fig. 1.

Approach to treatment of RAS

Topical Treatments

Topical Antiseptics, Anti-inflammatory and Analgesics

Topical treatment with antiseptics and analgesics should be continued as long as lesions persist. Use of 0.2% chlorhexidine or triclosan in rinse or gel form and 0.3% diclofenac with 2.5% hyaluronic acid applied topically can provide effective relief in majority of minor ulcers [28, 29]. Application should be 2 to 4 times a day without swallowing the medications [29].

Another widely used and studied topical agent is amlexanox. It has anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic properties. Application in 5% concentration, two to four times a day provides effective healing, pain relief, reduction erythema and ulcer size. Multiple studies have shown amlexanox to be effective in minor ulcers [30, 31].

Topical Antibiotics

Topical tetracycline, doxycycline and minocycline are used in treating RAS. They inhibit metalloproteinases and collagenases that are involved in tissue destruction and ulcer formation. They also exert immunomodulatory effect. Doxycycline is known to have best inhibitory effect on metalloproteinases [32]. A meta-analysis identified that a single application of doxycycline is associated with reduced healing time compared to control group but without reduction in pain [33]. Doxycycline 100 mg dissolved in 10 ml of water with rinses, four times a day can be effective.

Topical Corticosteroids

In treating RAS, topical corticosteroids are one of the effective agents in reducing pain and healing time. Based on the severity of the disease, these can be preferred as per their potency. In order of lesser to greater potency, we have triamcinolone acetonide, fluocinolone acetonide or clobetasol propionate for use in patients with RAS. Table 7 provides the dosing schedule of three topical steroids [34]. A systematic review of eight randomized controlled trials reported that topical corticosteroids are effective in pain relief. Healing time reported in six studies was observed to be shorter with active treatment than placebo. Prevention of recurrence was reported only in one study. Therefore, it was concluded that the use of topical steroids reduced pain and decreased healing time. Evidence on reduction of recurrences was inconclusive [35]. Comparatively, topical dexamethasone has shown to be equally effective in RAS [36].

Table 7.

Topical corticosteroids for RAS

| Steroid | Concentration | Application | Disease severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triamcinolone acetonide | 0.05–0.5% | 3–5 times/day | Small, mild erosive |

| Fluocinolone acetonide | 0.025–0.05% | 3–5 times/day | More aggressive lesions |

| Clobetasol propionate | 0.025% | 3–5 times/day | Moderate to severe |

Topical Anaesthetics

Topical lidocaine has been used for pain relief in RAS. A small study from France reported significant pain relief with 1% lidocaine cream use [37]. Another study proved that topical 2% lidocaine along with 1:80000 topical adrenaline solution is effective in early phase of RAS providing faster and complete relief of pain [38]. However, repeated application should be avoided or minimized to prevent possible toxicity [39]. In patients with a posterior ulcer, chewable lignocaine may be useful.

Other Treatments

Hyaluronic acid (HA) 0.2% gel applied twice a day can provide effective pain relief. A systematic review of nine clinical trials involved 538 RAS patients, 259 in the hyaluronic group. Comparative groups included triamcinolone (3 studies), chlorhexidine, lidocaine, placebo, iodine glycerine, diclofenac, and laser therapy. HA was observed to have good efficacy in reducing pain and decreasing the healing time. In comparison to topical corticosteroid, HA had superior results in one study, and comparable results in two studies. However, there was heterogeneity of the included studies with high risk of bias [40]. Nonetheless, HA may be efficacious. Further randomized controlled studies are needed.

In recent years, Lasers have emerged as successful and effective treatments for RAS. Various lasers such as Nd:YAG laser ablative, CO2 laser (applied through a transparent gel, non-ablative) and diode laser (low-level laser treatment mode) are used for treatment. In Systematic review of 11 studies with 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), lasers were effective in providing significant pain relief immediately after treatment and pain relief even persisted over few days. It also decreased the duration of healing. The comparators included placebo, and topical corticosteroids [41].

Among natural substances, substances which have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties such as myrtle (Myrtus communis), quercetin, licorice hydrogel and aqueous extract of Damask rose can be useful [34]. A combination gel containing rhubarb extract and salicylic acid has also shown reduce to pain in RAS [42]. A meta-analysis of 11 studies assessing various natural substances in RAS identified decrease in pain and reduction in ulcer size with select natural substances. However, many studies had high risk of bias [43]. These may be considered as adjunct to other topical or systemic treatments.

Systemic Treatments

Systemic treatments are necessary when topical treatments are not effective or the disease is severe and when there are frequent recurrences. A vast variety of systemic medications have been tried and studied. Majority of medications are directed towards pain reduction, ulcer healing and reducing recurrences.

Levamisole had shown to be effective drug in the studies conducted three decades ago [44, 45]. By virtue of its immunomodulatory effects, it provides effective relief in RAS. In a dose of 50 mg three times daily for one to three months, it reduces ulcers in nearly two-third of patients [8]. Prophylactic use does not prevent the recurrences in RAS [46].

Systemic corticosteroids are useful in severe disease. In our experience, oral prednisolone and deflazacort has shown to provide effective relief in RAS. In RAS unresponsive to topical steroids for over 4 months, systemic corticosteroids provided effective pain relief, ulcer healing and reduced recurrence [47]. The duration of systemic steroids should be limited to two months [8].

Nutritional supplements in the form vitamin B12, iron and zinc can be helpful in treating RAS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Volkov et al. reported significant reduction in pain, duration of outbreaks, and the number of ulcers with supplementation of vitamin B12. It was effective irrespective of serum vitamin B12 levels. By the end of five months of treatment, significantly higher proportion of patients had no aphthous ulcer status [48]. Zinc administration also reduced number of ulcers, ulcer size and activity periods [49].

Other immunomodulators such as thalidomide, colchicine, dapsone have been used effectively in managing RAS [8]. Comparative analysis of these agents showed thalidomide as better drug to provide remission compared to dapsone, colchicine, and pentoxifylline [50]. The unwanted side effects of these drugs limits their use. Thus, their use is restricted in severe cases only. One report indicated successful use of etanercept in recalcitrant RAS [51].

Rebamipide is a quinolinone derivative that has been used in RAS for ulcer healing. It acts by preserving the existing cells and aiding replacement of lost tissue [50]. It preserves the cells by increasing the concentration of prostaglandin E2 and prostaglandin I2, increase in blood flow by increasing nitric oxide synthase activity, reducing the expression of neutrophil adhesion molecules such as CD11b, CD18, reducing the secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha by inhibiting the synthesis of E-selectins, and neutralizing free radicals by antioxidant activity. It replaces the lost tissue by increasing the expression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and its receptors thereby improving the angiogenesis, granulation tissue and epithelialization [52]. Multiple observational studies from India have proved that rebamipide effectively reduced pain, accelerated ulcer healing, reduces recurrences and has acceptable safety profile [53, 54]. A study from South India reported that rebamipide 100 mg three times daily for one week had similar efficacy to that of levamisole by the end of four week. Rebamipide was well tolerated without significant adverse effects [53]. Another study from Delhi compared the topical fixed dose combination of choline salicylate, benzalkonium chloride, and lignocaine to the combination of topical amlexanox and oral rebamipide. Study observed combination of topical amlexanox and oral rebamipide to be more efficacious with healing of ulcers at an accelerated rate [55]. A study from Pune evaluated thirty patients with aphthous ulcerations treated with amlexanox (5%) paste to be applied 4 times a day, rebamipide 100 mg three times a day and combination of both. All treatments were continued till ulcer healing. By end of day 7 follow-up, combination group was found to be associated with reduced healing time, ulcer size, the duration of pain compared to each monotherapy group [56]. These data indicate good efficacy and tolerability of rebamipide in aphthous ulcers and RAS.

Anti-reflux drugs can be useful in patients who have not responded to conventional treatments. The gastric reflux could be the cause for RAS especially when recurrences are frequent. A meta-analysis of seven case control studies observed significantly higher rates of RAS in patients who had Helicobacter pylori infection [57]. Few reports indicate remission of RAS with use of anti-reflux drugs along with H. pylori eradication resulted in resolution of RAS [58]. Given the stress as an important factor in RAS as well as in acid reflux, use of these drugs can be helpful in correctly identified patients. Alternatively, patient with RAS not responding to other conventional treatments might be investigated for H. pylori disease.

Though Anxiolytics and Antidepressants are not front-line treatments in RAS, they might be useful in select cases. As psychological stress and/or anxiety are identified to be important contributor to RAS [59, 60], these group of drugs can be helpful in patients with high stress levels or who are anxious or depressed.

Consensus: The aim of treatment is to reduce pain, accelerate healing, reduce the recurrences and improve quality of life. Choice of treatment is dependent on how quickly patient wants relief. Initial approach may be more conservative and therefore topical agents are the first choice. Counselling and reassurance should be done. Systemic treatments should be opted when there is no effective response to topical therapy or disease presents with major ulcers, multiple ulcers, or recurrences are frequent. Use of systemic steroids, and analgesics should be for limited duration. Rebamipide is a systemic agent that may be used before a trial of steroids or other immunosuppressants. For early and effective relief, combination treatments are useful in RAS. In selected cases, use of anti-reflux drugs, anxiolytic may be useful.

Consensus 7: Prevention of Recurrence

Avoiding the precipitating factors, routine supplementation of vitamins, zinc and iron, avoiding foods causing hypersensitivity and oral products containing sodium lauryl sulphate can reduce the recurrences. Use of mouthguard while sleeping can also be helpful. Avoiding stress and minimizing stress with effective exercise and meditation can help reduce the recurrences.

Consensus: Avoiding precipitating factors should be done to prevent the recurrences in RAS.

Conclusion

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is commonly encountered clinical condition. We suggest that three or more episodes of aphthous ulcer in a given year should be considered as RAS. The etiology of RAS is usually idiopathic and multifactorial. Multiple trigger factors can lead to multiple episodes of ulcerations. Reducing the stressors can reduce the recurrences. Primary aim of treatment is to reduce the pain, accelerate ulcer healing, reduce the recurrences and improve the quality of life. In manging patients with RAS, topical therapy with reassurance should be initial approach. Systemic treatments are necessary as part of initial therapy in severe disease or in those with frequent recurrences. The use of combination treatments involving topical and systemic agents can be an effective approach to manage RAS.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Vijay Katekhaye (Quest MedPharma Consultants, Nagpur, India) for editorial assistance.

Ethical Approval

and informed consent: Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the development of consensus. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sameer Bhargava and Jagtap Charuhas and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Author sequence is as per the alphabetical order of the last name.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Samir Bhargava, Email: drsamirbhargava@yahoo.co.in.

Satya Prakash Dubey, Email: satyapdubey11@gmail.com.

Deepak Haldipur, Email: deepakhaldipur@gmail.com.

Charuhas Jagtap, Email: charujagtap@gmail.com.

Shriram Vasant Kulkarni, Email: dr.svk88@gmail.com.

Ashwin Kotamkar, Email: ashwink@macleodspharma.com.

Parthasarathy Muralidharan, Email: drparthasarathym@macleodspharma.com.

Pradeep Kumar, Email: entpradeepkumar@gmail.com.

Amit Qamra, Email: dramitq@macleodspharma.com.

Abhishek Ramadhin, Email: drabhishekkumar4u@gmail.com.

Sreenivasan Venkatraman, Email: drsreenivenkat@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Tarakji B, Gazal G, Al-Maweri SA, Azzeghaiby SN, Alaizari N. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis for dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:74–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirowski GW, Rosengard HC, Messadi DV (2020) What is the global prevalence of aphthous stomatitis (canker sore)? https://www.medscape.com/answers/1075570-61400/what-is-the-global-prevalence-of-aphthous-stomatitis-canker-sore Accessed 20 May 2022

- 3.Bhatnagar P, Rai S, Bhatnagar G, Kaur M, Goel S, Prabhat M. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions, mucosal variants, and treatment required for patients reporting to a dental school in North India: in accordance with WHO guidelines. J Family Community Med. 2013;20:41–48. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.108183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil S, Reddy SN, Maheshwari S, Khandelwal S, Shruthi D, Doni B. Prevalence of recurrent aphthous ulceration in the indian Population. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6:e36–40. doi: 10.4317/jced.51227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao AK, Vundavalli S, Sirisha NR, Jayasree CH, Sindhura G, Radhika D. The association between psychological stress and recurrent aphthous stomatitis among medical and dental student cohorts in an educational setup in India. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2015;13:133–137. doi: 10.4103/2319-5932.159047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Queiroz SIML, Silva MVAD, Medeiros AMC, et al. Recurrent aphthous ulceration: an epidemiological study of etiological factors, treatment and differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:341–346. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu K, Zhou C, Huang F, et al. Relationship between dietary factors and recurrent aphthous stomatitis in China: a cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:03000605211017724. doi: 10.1177/03000605211017724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Challacombe SJ, Alsahaf S, Tappuni A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: towards evidence-based treatment? Curr Oral Health Rep. 2015;2:158–167. doi: 10.1007/s40496-015-0054-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A, Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:306–321. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoppay JR (2020) Aphthous Ulcers Clinical Presentation. Available from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/867080-clinical Accessed on 20 May 2022

- 11.Preeti L, Magesh K, Rajkumar K, Karthik R. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:252–256. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.86669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi L, Wan K, Tan M, et al. Risk factors of recurrent aphthous ulceration among university students. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:6218–6223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zain RB. Oral recurrent aphthous ulcers/stomatitis: prevalence in Malaysia and an epidemiological update. J Oral Sci. 2000;42:15–19. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.42.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maheswaran T, Yamunadevi A, Ilayaraja V, et al. Correlation between the menstrual cycle and the onset of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Indian Acad Dent Spec Res. 2015;2:25–26. doi: 10.4103/2229-3019.166117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajmane YR, Ashwinirani SR, Suragimath G, et al. Prevalence of recurrent aphthous stomatitis in western population of Maharashtra, India. J Oral Res Rev. 2017;9:25–28. doi: 10.4103/jorr.jorr_33_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur R, Behl AB, Punia RS, Nirav K, Singh KB, Kaur S. Assessment of Prevalence of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis in the North Indian Population: a cross-sectional study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13:S363–S366. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_581_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akintoye SO, Greenberg MS (2014 Apr) Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dent Clin North Am. 58:281–. 10.1016/j.cden.2013.12.002. 2 97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wardhana, Datau EA. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis caused by food allergy. Acta Med Indones. 2010;42:236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright A, Ryan FP, Willingham SE, et al. Food allergy or intolerance in severe recurrent aphthous ulceration of the mouth. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:1237–1238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6530.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sari RK, Ernawati DS, Soebadi B. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis related to psychological stress, food allergy and GERD. ODONTO: Dent J. 2019;6:45–51. doi: 10.30659/odj.6.0.45-51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Q, Ni S, Fu Y, Liu S. Analysis of Dietary related factors of recurrent aphthous stomatitis among College Students. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;27:2907812. doi: 10.1155/2018/2907812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koybasi S, Parlak AH, Serin E, Yilmaz F, Serin D. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: investigation of possible etiologic factors. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiang CP, Yu-Fong Chang J, et al. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis - etiology, serum autoantibodies, anemia, hematinic deficiencies, and management. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yıldırımyan N, Özalp Ö, Şatır S, Altay MA, Sindel A. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis as a result of Zinc Deficiency. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2019;17:465–468. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a42736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Maweri SA, Halboub E, Al-Sharani HM, et al. Association between serum zinc levels and recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:407–415. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozturk P, Belge Kurutas E, Ataseven A. Copper/zinc and copper/selenium ratios, and oxidative stress as biochemical markers in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013;27:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim YJ, Choi JH, Ahn HJ, Kwon JS. Effect of sodium lauryl sulfate on recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Oral Dis. 2012;18:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saxen MA, Ambrosius WT, Rehemtula al-KF, Russell AL, Eckert GJ. Sustained relief of oral aphthous ulcer pain from topical diclofenac in hyaluronan: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:356–361. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altenburg A, El-Haj N, Micheli C, Puttkammer M, Abdel-Naser MB, Zouboulis CC. The treatment of chronic recurrent oral aphthous ulcers. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:665–673. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhat S, Sujatha D. A clinical evaluation of 5% amlexanox oral paste in the treatment of minor recurrent aphthous ulcers and comparison with the placebo paste: a randomized, vehicle controlled, parallel, single center clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24:593–598. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.123382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng W, Dong Y, Liu J, et al. A clinical evaluation of amlexanox oral adhesive pellicles in the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and comparison with amlexanox oral tablets: a randomized, placebo controlled, blinded, multicenter clinical trial. Trials. 2009;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skulason S, Holbrook WP, Kristmundsdottir T. Clinical assessment of the effect of a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor on aphthous ulcers. Acta Odontol Scand. 2009;67:25–29. doi: 10.1080/00016350802526559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Maweri SA, Halboub E, Ashraf S, et al. Single application of topical doxycycline in management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available evidence. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:231. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01220-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belenguer-Guallar I, Jiménez-Soriano Y, Claramunt-Lozano A (2014) Treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. A literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. Apr 1;6(2):e168-74. doi: 10.4317/jced.51401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Quijano D, Rodríguez M. Topical corticosteroids in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Systematic review. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2008;59:298–307. doi: 10.1016/S0001-6519(08)73314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Zhou Z, Liu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of dexamethasone ointment on recurrent aphthous ulceration. Am J Med. 2012;125:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Descroix V, Coudert AE, Vigé A, et al. Efficacy of topical 1% lidocaine in the symptomatic treatment of pain associated with oral mucosal trauma or minor oral aphthous ulcer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-dose study. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akhionbare O, Ojehanon PI. The Palliative Effects of Lidocaine with adrenaline on recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS) J Med Sci. 2007;7:860–864. doi: 10.3923/jms.2007.860.864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita S, Sato S, Kakiuchi Y, Miyabe M, Yamaguchi H. Lidocaine toxicity during frequent viscous lidocaine use for painful tongue ulcer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002;24(5):543–545. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Maweri SA, Alaizari N, Alanazi RH, et al. Efficacy of hyaluronic acid for recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review of clinical trials. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:6561–6570. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suter VGA, Sjölund S, Bornstein MM. Effect of laser on pain relief and wound healing of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32:953–963. doi: 10.1007/s10103-017-2184-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khademi H, Iranmanesh P, Moeini A, Tavangar A. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the iralvex gel on the recurrent aphthous stomatitis management. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;14:175378. doi: 10.1155/2014/175378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips KS, Carrillo Medina WC, Potter JM, Al-Eryani K, Enciso R. Systematic review with meta-analyses of natural products in the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Int J Oral Dent Health. 2019;5:103. doi: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Symoens J, Brugmans J. Letter: treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and herpes with levamisole. Br Med J. 1974;4:592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5944.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson JA, Silverman S., Jr Double-blind study of levamisole therapy in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol. 1978;7:393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.16000714.1978.tb01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weckx LL, Hirata CH, Abreu MA, Fillizolla VC, Silva OM. Levamisole does not prevent lesions of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Rev Assoc Méd Bras. 1992;55:132–138. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302009000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Femiano F, Gombos F, Scully C. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis unresponsive to topical corticosteroids: a study of the comparative therapeutic effects of systemic prednisone and systemic sulodexide. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:394–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volkov I, Rudoy I, Freud T, Sardal G, Naimer S, Peleg R, Press Y. Effectiveness of vitamin B12 in treating recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:9–16. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merchant HW, Gangarosa LP, Morse PK, Strain WH, Baisden C. Zinc sulfate as a Preventive of recurrent aphthous ulcers. J Dent Res. 1981;60A:609–611. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mimura MA, Hirota SK, Sugaya NN, et al. Systemic treatment in severe cases of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: an open trial. Clin (Sau Paulo) 2009;64:193–198. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322009000300008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson ND, Guitart J. Recalcitrant, recurrent aphthous stomatitis treated with etanercept. Arch Derm. 2003;139:1259–1262. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.10.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meghanadh KR, Kaur M, Haldipur D, et al. Rebamipide in Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: review of indian evidence. Indian Pract. 2021;74:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parvathidevi MK, Ramesh DN, Shrinivas K. Efficacy of rebamipide and levamisole in the treatment of patients with recurrent aphthous ulcer-a comparative study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(11):ZC119–Z122. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10295.5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jadhav A, Marathe S, Mhapuskar A. To evaluate the efficacy of rebamipide on clinical resolution and recurrence of minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Int J Dent Health Sci. 2015;2:781–797. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hasan S, Perween N, Saeed S, Kaur M, Gombra V, Rai A. Evaluation of 5% amlexenox oral paste and Rebamipide Tablets in treatment of recurrent apthous stomatitis and comparison with Dologel CT. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;27:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01858-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uppalwar P, Kunjir G, Krishna Kumar R, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effect of topical Amlexanox (5%), and oral Rebamipide (100 mg) in the management of oral aphthous ulceration. J Oral Dent Health. 2016;2:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li L, Gu H, Zhang G. Association between recurrent aphthous stomatitis and Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18:1553–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00784-014-1230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao Y, Gupta N, Abdalla M. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis improved after eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2021;30:5543838. doi: 10.1155/2021/5543838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gallo CD, Mimura MA, Sugaya NN. Psychological stress and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Clinics. 2009;64:645–648. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000700007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zakaria M, Hosny R. Relation between salivary cortisol and alpha amylase levels and anxiety in egyptian patients with minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Egypt Dent J. 2018;64:1235–1243. doi: 10.21608/edj.2018.77378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]