Abstract

Congenital and pediatric nasal lesion resection and their reconstructive outcomes are not well studied. A surgeon must consider the site, depth, size, age, etiology and effect on future function (including growth).

The path of total reconstruction or of portions of the cartilaginous / cutaneous nasal structure in the pediatric patient must undergo a series of totally different needs with respect to the management of the adult.

First of all, it is essential to understand at what age to intervene, given that the child in the growth phase up to adolescence sees the nasal skeleton change significantly and in relation to the possible psychological repercussions that the tissue deficit can cause. This path will often require serious interventions in order to recreate a structure that is aesthetically ideal, functionally effective and finally suitable for the growth phase of the rest of the body and facial structures.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12070-022-03364-y.

Keywords: Nasal wing cleft, Forehead flap, Pediatric surgery, Nasal reconstruction

Introduction

The nose is the most central and prominent anatomical part of the face and it is a fundamental element of the aesthetic aspect; therefore the surgical approach to this area is extremely complex with regard to what concerns the psychosocial relapses that a nose defect entails.

For a long time there has been discussion about possible surgical solutions that can be selected on the basis of surgical perspective, the nature of the nasal lesion dictates the most appropriate approach to reconstruction.

A lot of factors are considered, such as the size and depth of the tissue gap, as well as whether cartilaginous and bony components of the nasal structure are involved in addition to the overlying skin and mucosa.

In this work a case of a full thickness right nose cleft is presented in a 4 year old male patient. After careful evaluation of the case and taking into account the young age of the patient a multi-step reconstruction, using a peduncolated forehead flap, was performed.

Specialists realized from past centuries that the forehead is an excellent donor area for nasal defects, with good match for color and texture[1],

Many articles have been written about the history, techniques, and outcomes of nasal reconstruction with a forehead flap. This type of reconstruction has become the standard for nasal reconstruction, and the results obtained by following their principles are self-evident [2].

In order to achieve the best aesthetic results, the surgeon must have a tridimensional vision to evaluate exactly the dimensions of the resulting defect, the damaged structures, and also he must have significantly good knowledge about the local nasal anatomy due to a region with complex contours with intersecting concavities and convexities [3].

It is decidedly incorrect to consider the child simply a young adult to approach the surgical level in the exact same way.

Children’s noses are generally less defined, flatter, and more uniform in skin texture and thickness. It is also important to consider the risk of growth impairment and the type of nasal lesions that occur in this age group.

Case Report

In November 2018, 4 year-old patient comes to Maxillofacial department affected by a right nasal cleft/right nasal wing agenesis.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative image of the patient at the age of 4

After a careful case study a surgical approach consisting of 3 steps was proposed, including a paramedian pedunculated frontal flap based on the supratrochlear vessels to reconstruct the internal and external lining of the deficient right nasal wing and a cartilage graft of the auricular concha.

Primarly, the different subunits constituting the healthy were designed, calculating the size of the tissue gap with a caliber. A template was modeled on the basis of the altered anatomy of the patient in order to be able to correctly design, at the level of the paramedian frontal region, the flap to be sculpted.

Then the right nasal subunits affected by cleft were delimitated and gory. The forehead flap based on right sovrathrocheal vessels was transfer to reconstruct the nasal defect to recreate the inner and outer right nasal wing lining. A nasal conformator was positioned.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative image of the first surgery with preparation of the Forehead pedunculated flap

After 2 month skin incision was made in the edge of the nostril to make the internal lining autonomous and debulking. In the same session the cartilage graft of the contralateral auricular concha was lodged and the flap was repositioned above the cartilage to offer an adequate receiving bed, leaving the pedunculated flap only for the external lining.

Also in this case nasal conformator on the right cavity was positioned.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative image of the second revision surgery of the forehead flap with reconstruction of the cartilage of the right nasal wing by means of ear cartilage graft

After 30 days, third step was performed: resection of the vascular pedunculum of the previously prepared right paramedian frontal flap. The lining of right nasal wing was reconstructed. This last procedure included a revision of paramedian frontal scar.

At this stage, it is the author’s opinion to leave some excess tissue of the flap, in order to compensate for the absence of growth of the same in the following years and the possible scar retractions, during the developmental phase of the young patient.

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative image of the third intervention of trimming and autonomization of the flap with primary refinements

The patient was constantly followed after the conclusion of the third surgery, monitoring the aesthetic aspect that occurred once the post-surgery edema was reabsorbed and above all by ensuring that the functionality of nasal breathing through the nostril affected by the cleft was restored.

Fig. 5.

Post-operative image 6 months after the last surgery

Discussion

Restoring nasal contours and achieving an aesthetically pleasing result can be quite challenging. Reconstruction should be a thoughtful, comprehensive process with meticulous preoperative analysis of the lesion, resulting in defect and various reconstructive options [4].

Most descriptions of nasal reconstruction in children focuses on cancer or traumas. A significant number of acquired nasal defects in children are caused by head and neck injuries, particularly dog bites [5].

The nasal anatomy is also unique and the complexity of its configuration renders it vulnerable to distortion and damage. The nose comprises tissues of variable consistency and quality, arranged so as to create a tripod lined with olfactory epithelium.

A very small number of articles dealt with congenital nasal lesions which have estimated the incidence as a rate of 1–4%; so they are a very rare entities.

Nasal deformities can present as isolated defects or form part of wider pathology including craniofacial syndromes atypical clefts and underlying neoplastic or benign lesions [6].

Certainly, the pediatric patient who requires nasal reconstruction must be approached as a unique surgical entity.

Nasal reconstruction has been studied extensively in adults but limited literature exists for congenital and pediatric lesions and their reconstruction.

About congenital and pediatric nasal lesions, it is important to contrast the differences between the adult and child’s nose, such as the consequences of the surgery on the child’s growth and psychological well-being. In addition, the surgical approach is uniquely “anticipatory” in children;

one major difference is the anatomic changes that occur during development of the nose. It is necessary to consider planning for future corrective surgery, often required at the end of the growth, by preserving potential facial graft tissue. Several anatomical studies show that the face changes entirely during the first decade of life [5, 10, 11].

These early studies into isolated congenital alar defects demonstrated that nasal and alar regions develop separately from different mesenchymal fields. As such, the alar cartilages may develop with abnormalities separate to the remaining nasal soft tissue and therefore present as congenital isolated deformities [6].

Nasal development is considered finished at the age of 16, when it finally becomes a risen pyramid with a triangular base [3].

About the reconstruction process we can state that the peduncolated forehead flap is perfect considering the anatomy and tissue characteristics of the surrounding areas, in this case, of the frontal region; not only for the relative simplicity of setting up because the tint of the skin of the forehead matches that of the nasal skin. It is a little too thick, however, and needs to be thinned to achieve a contour that is acceptable cosmetically [7, 8].

Like in this presented case, with large nasal defect, surgeons used to consider first the functional aspect of the procedure [9, 10].

Nowadays, the main goal is to achieve a functional nose with good aesthetic outcomes. A soft tissue defect can be covered only with a skin graft, but the texture and the contour will not resemble to the natural aspect of the nose.Other local flaps do not provide sufficient soft tissue (skin and subcutaneous tissue)t o cover large defects [11, 12].

An additional consideration in treating congenital and pediatric nasal lesions is the psycho-social factors. As a child becomes more self-conscious and gains self-esteem, having a nasal deformity or lesion can be devastating to a child’s self-image. We recommend that reconstruction should be attempted prior to the child starting school. As such our median age was 5.4 years of age.

At the check one year after the third surgery, as shown in the pictures, it was possible to appreciate the complete adaptation of the young patient to the functional aesthetic result achieved, in fact he manages to breathe adequately from both nostrils. The margins of the pedunculated flap have perfectly healed with the adjacent pre-existing tissues, and the auricular concha cartinaginous graft has correctly integrated into the nasal skeleton.

Aesthetically, the result can be defined as satisfactory in relation to the starting tissue deficit and the young age of the patient; which in the years to come, will have to undergo further corrective plastic surgery in the dome-columellar compartment, the orientation of the nasal tip, and the modification of the size of the nostrils.

On average, the reconstructive process consists of 4 interventions including retouching; being a patient of advanced age, it is not recommended to make special touch-ups so we have limited ourselves to filling the tissue gap with acceptable aesthetics and function in order to then satisfy the most ambitious aesthetic needs once the growth is complete.

The main refinements that are carried out are: debulking, trimming, lipofilling, rhinofiller, scar revision, to then move on to a primary rhinoseptoplasty.

Obviously primary rhinoseptoplasty is a highly invasive procedure in a growing structure, which is always to be avoided unless explicitly requested by the patient who do not accept their appearance (on average from the age of 8) or by parents and always involves an increase in difficulty in secondary rhinoseptoplasty at the age of 18.

Otherwise, if there is good acceptance from an aesthetic and functional point of view, the growth is usually expected to be completed around 18 years of age.

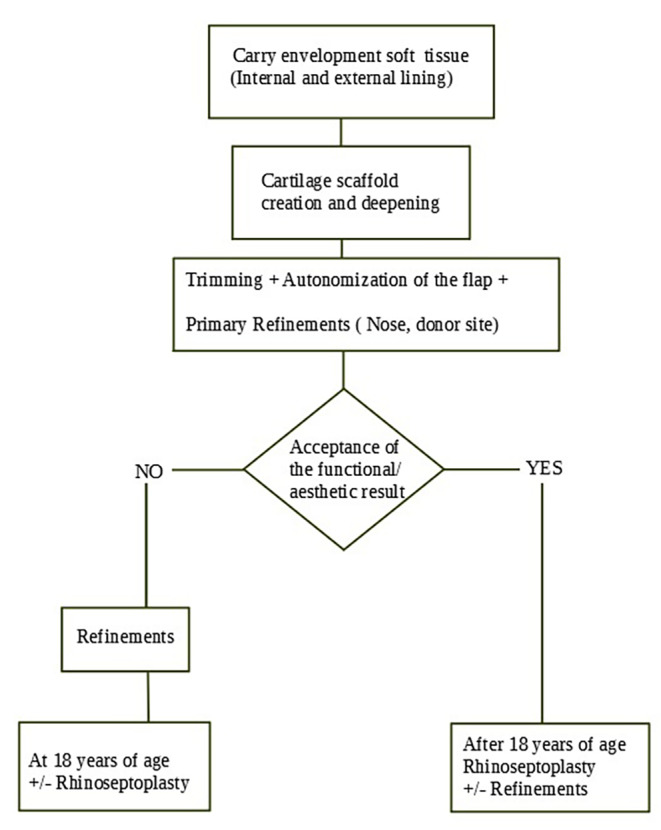

Tab. 1.

Multi-step algorithm for pediatric nasal reconstruction

Conclusion

The repair of a nasal defect in the pediatric patient presents a significant challenge to the plastic surgeon. The challenge involves numerous considerations beyond the nature of the defect itself, such as the child’s growth and psychosocial well-being and social inclusion. These are in themselves ever-evolving concepts, which need to be reappraised by the surgeon and the patient on a continuous basis.

The ultimate goal is to obtain good final contour and satisfactory scar. Meticulous, layered closure, with appropriate eversion of the edges is essential. Adjunctive procedures can correct the visibility of a scar created if necessary subsequently. The achievement of good contour and a smooth transition between native tissue and reconstruction is essential to accomplishing a successful reconstruction.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors report no involvement in the research by the sponsor that could have influenced the outcome of this work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The treatment of the presented patient was not in any way influenced due to this article.

Informed Consent

The patient provided informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Francesco Giovacchini, Email: f.giovacchini@ospedale.perugia.it.

Gabriele Monarchi, Email: gabriele.monarchi@gmail.com.

Valeria Mitro, Email: valeria.mitro@ospedale.perugia.it.

Massimiliano Gilli, Email: massimilianogilli0@gmail.com.

Antonio Tullio, Email: antonio.tullio@unipg.it.

References

- 1.Cioaru B, Dragu E, Lascar I. Nose Defects Reconstruction with Forehead Flap – Case Report. MAEDICA – a Journal of Clinical Medicine 2014; 9(1): 76–78 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Burget GC, Menick FJ. Aesthetic Reconstruction of the Nose. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994

- 3.Giugliano C, Andrades PR, Benitez S. Nasal reconstruction in a forehead flap in children younger than 10 years of age. Plast Recon Surg 2004;114:316–325 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wolfswinkel EM, Fahradyan A, Tsuha M, Goel P, Starnes-Roubaud (2019 Sep;) J Craniofac Surg. 30:1777–1779Less Is More in Congenital and Pediatric Nasal Lesions6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.O’Rourke SCM, Neiva C, Galliani E (2019 Jun;) ediatric Nasal Reconstruction by Washio Procedure. 35:286–293. 10.1055/s-0039-1688703. Epub 2019 May 17 PFacial Plast Surg3. doi: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ujam AB, Bulstrode NW (2019 Mar;) Modified reconstructive technique for paediatric congenital alar rim deformity. 118:201–205Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shokri T, Kadakia S, Saman M The Paramedian Forehead Flap for Nasal Reconstruction: from antiquity to Present.J Craniofac Surg. 2019 Mar/Apr; 30(2):330–333 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Menick FJ. Nasal Reconstruction Art and Practice. New York: Mosby/ Elsevier, 2009

- 9.Rochrich RJ, Griffin JR, Ansari M, et al. – Nasal Reconstruction – Beyond Aesthetic Subunits: A 15-year Revew of 1334 Cases.Plast Reconstr Surg2004; 11:1405 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Angobaldo J, Marks M. Refinements in Nasal Reconstruction – The cross-Paramedian Forehead Flap.Plast Reconstr Surg2009; 123:87 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Alfort EL, Baker SR, Shumrick KA. Midforehead flaps. In: Baker SR, Local flaps in Facial reconstruction. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995: 197–223

- 12.Ebrahimi A, Kalantar Motamedi MH, Nejadsarvari N, et al. Subcutaneous Forehead Island Flap for Nasal Reconstruction.Iran Red Crescent Med J2012; 14:271–275 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.