Abstract

Purpose: The main purpose of this study is to understand the characteristics and management of sinonasal small round blue cell tumors and also to emphasise the role of immunohistochemistry in their diagnosis and on the outcomes after endoscopic/open excision in these patients. Methods: This is a retrospective study conducted at a tertiary care referral centre in India which included 38 patients with sino nasal for a period of 5 years. All the patients were evaluated clinically and radiologically. All cases were confirmed diagnostically with histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry following surgical excision either by endoscopic or open approach. Some of the cases underwent post operative radiotherapy. Results: In our study, among 176 cases diagnosed with Sino nasal malignancies, 38 (21.6%) cases were diagnosed with sinonasal small round blue cell tumors with male to female ratio 1.4:1. Most common histopathological type among all the sinonasal small round blue cell tumors that presented to us was esthesioneuroblastoma i.e., 8 (21%) patients followed by pituitary macroadenoma in 7(8.4%) patients. Other types are undifferentiated squamous cell carcinoma 10(13.1%), craniopharyngioma 8(10.5%), lymphoma 3(7.9%), synovial/spindle cell sarcoma, malignant melanoma and adenocarcinoma 1(2.6%) each. Schwannoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma and neurofibroma 2 (5.2%) each. Conclusion: Sinonasal small round blue cell tumors are extremely rare tumours. Histopathological diagnosis with immunohistochemistry is characteristic of various tumors and is conclusive for diagnosis. Knowledge of these tumor entity is essential as early diagnosis helps in further management in preventing spread to vital structures and improving outcome. Most of the tumors have a multimodality treatment approach which includes surgical excision, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Keywords: Sinonasal malignancies, Small round blue cell tumours, SRBCT’s immunohistochemistry, Malignant melanoma, Synovial sarcoma, Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, Esthesioneuroblastoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, Schwannoma, Spindle cell tumour, Endoscopic excision, Radiotherapy

Introduction

Sinonasal malignancies (SNM) are rare tumors and represent around 1% of all malignancies and 3 to 5% of all head and neck cancers [1]. They can arise either directly from the paranasal sinuses (PNS) or via extension from the adjacent structures. Primary epithelial tumours are the most common type of SNM.2 Symptoms usually develop late as a result of which the diagnosis is delayed and patients present only at a relatively advanced stage. Nasal endoscopy is important for initial clinical diagnosis. Radiological imaging in the form of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are critical and complimentary in management of SNM. Imaging not only helps to characterise the tumour and assess the regional and local extension but also aids in the planning of surgery and adjuvant treatments. MRI provides superior soft tissue resolution helping in assessment of soft tissue masses and also to know the extent of the tumour outside the confines of the PNS. CT PNS helps in assessment of bony margins of the PNS and skull base which are less effectively demonstrated on MRI. Surgery and radiotherapy/chemotherapy continue to be the mainstay of treatment [2].

One of the most challenging diagnostic categories within tumours of the sinonasal tract is the small round blue cell tumors (SRBCT’S). The various tumors included in this series are malignant epithelial (Small cell carcinoma neuroendocrine type, Sinonasal undifferentiated cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma (non keratinising type), neuroectodermal (Ewings sarcoma, esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB), mucosal malignant melanoma), mesenchymal (desmoplastic SRBCT, rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma), Hematolymphoid (lymphoma, craniopharyngioma and plasmacytoma). Site of origin of the tumor, imaging and clinical findings combined with histopathological examination (HPE) and a panel of pertinent immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies and various molecular tests play a crucial role in reaching to a diagnosis of small round blue cell tumor category. The IHC panel may include epithelial marker (pancytokeratin such as AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen or OSCAR), a neuroendocrine marker (synaptophysin, chromogranin, or CD56), a muscle marker (desmin, myogenin, MYOD1), S100 protein, and CD45RB.3 It is very critical to distinguish between these neoplasms as there is significant differences in therapy and overall outcome. Some of these tumors are managed conservatively, some by primary radiotherapy or chemotherapy and others by multimodality therapy by extensive surgical excision by endoscopic approach or via external approaches, followed by radiotherapy or chemotherapy [2, 3].

The aim of this study is to understand and report the various aspects of sinonasal small round blue cell tumors by describing the demographics, clinical profile, diagnostic investigations and management options and also to emphasise the role of immunohistochemistry in their diagnosis and on the outcomes after endoscopic/open excision in these patients.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study which was conducted in the department of ENT and Head & Neck surgery at tertiary care referral centre in India. A retrospective review of complete records of all cases with confirmed histopathological diagnosis of SRBCT’S between the time period of 5 years between 2016 and 2021, were included in the study. Patients included were between 1 day to 80 years of age. Patients who were not willing to participate were excluded from the study.

Patients case sheets were reviewed, details about history regarding duration of symptoms, history of nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, headache, epistaxis, loss of smell, eye swelling, cheek swelling and nasal mass were all taken into consideration. History regarding wood dust exposure, and previous surgical interventions were also documented. Findings of DNE were documented. Detailed imaging findings on CT and MRI were all documented. (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

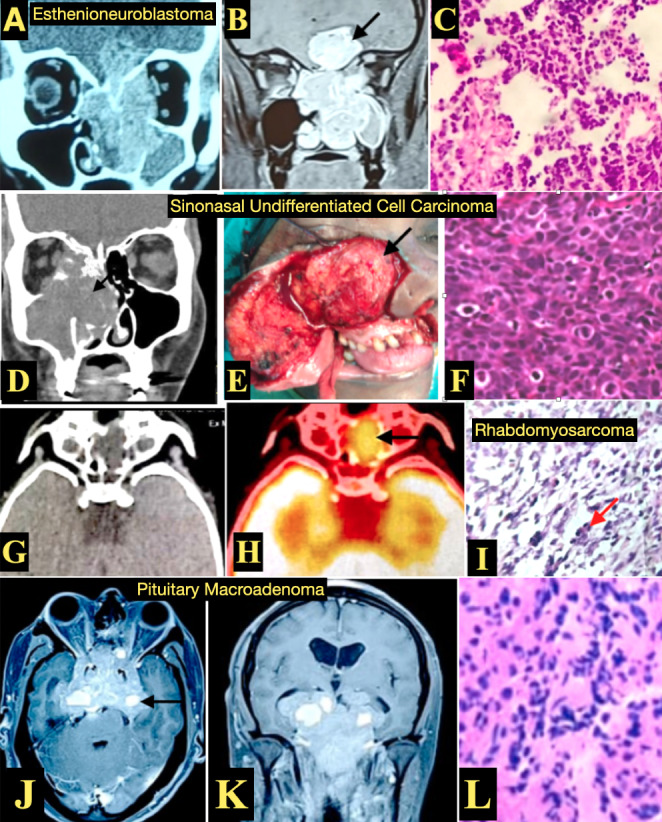

Fig. 1.

(A,B,C) Esthenioneuroblastoma: Imaging (A) CECT PNS coronal view, (B) MRI Brain and PNS, T1weighted with contrast coronal view showing a enhancing dumbbell shaped tumor (black arrow) in the left nasal cavity with intracranial extension (C) HPE with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain (H&E) showing nests of monotonous cells of SRBCT

(D,E,F) Sinonasal Undifferentiated Cell Carcinoma: (D) CT PNS coronal view showing soft tissue opacification involving the right nasal cavity and paranasal area with erosion of the lamina papyracea with extension into the orbit. (E) Intraoperative images showing tumor involving the right maxillary sinus (black arrow) which was excised by external approach using Weber Ferguson incision. (F) HPE with H&E stain showing small round cells presenting in nests and lobules with intracellular bridges

(G,H,I) Rhabdomyosarcoma: (G,H) CT PNS, axial view showing soft tissue in left ethmoidal and sphenoid sinus, with similar areas showing FDG uptake indicating metabolically active lesion on PET scan. (I) HPE images H&E stain High magnification showing SRBCT with hypercellular areas with loose myxoid stroma, perivascular condensation of sheets of round cells (red arrow) with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation

(J,K,L) Pituitary Macroadenoma: (J,K) MRI Brain and PNS, T1weighted with contrast (J) axial view and (K) coronal view showing enhancement involving the nose and PNS, extending into clivial and petrous regions with intracranial extensions. (L) HPE with H&E stain showing SRBCT which are chromophobic cells with abundant cytoplasm with stippled chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli

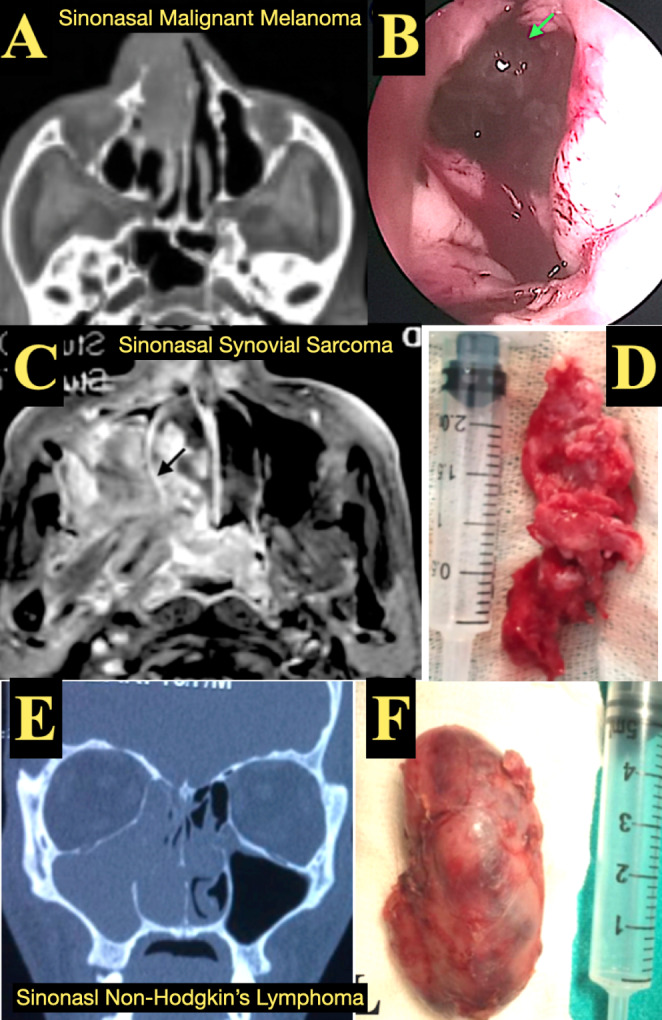

Fig. 2.

(A,B) Sinonasal Malignant Melanoma: (A) CT PNS axial view showing soft tissue opacification in the right nasal cavity. (B) Endoscopic view showing blackish coloured mucosal lesion (green arrow) with IHC positive for S-100 and HMB 45, (C,D) Synovial Sarcoma: (C). MRI T1 weighted Brain and PNS showing enhancement with contrast. (D) Excised gross specimen showing a fungating mass and IHC positive for S-100, TLE and BCL2 positive. (E,F) Sinonasal Non Hodgkins Lymphoma: (E) CT PNS coronal view showing soft tissue opacification in the right nasal cavity, maxillary sinus and ethmoid sinus. (F). Excised gross specimen from maxillary sinus with IHC positive for CD3 and CD5

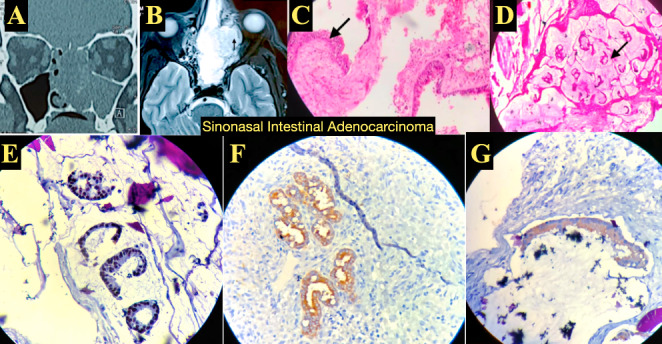

Fig. 3.

Sinonasal Intestinal Adenocarcinoma: (A) CT PNS coronal view showing soft tissue opacification involving the left maxillary sinus and nasal cavity. (B) MRI Brain and PNS, T1weighted, axial view showing enhancement with gadolinium contrast with extension into the orbit. (C,D) HPE with H&E stain staining showing (C) low magnification image showing pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with with ulceration and granulation tissue and (D) High magnification showing submucosal stroma with extensive areas of extracellular mucin pools with few floating glands. (E,F,G) IHC showing (E) CDX2 positive, (F) CK7 positive and (J) CK20 positive

All patients underwent preoperative routine investigations like blood grouping and typing, complete blood picture, RBS, renal and liver function tests, chest X-ray, ECG and a pre-anaesthetic check up in our anaesthesia department to evaluate fitness for surgery and a written informed consent was taken from the patient. Pre operative endoscopic examination of the nose was done and a biopsy from the mass was performed under local or general anaesthesia, and sent for HPE and IHC. The type of lesion was identified and the management was planned accordingly.

Surgeries were planned according to the condition of the patients and extent of the lesion. All patients were operated under general anaesthesia. The various procedures that were performed at our institute were complete endoscopic excision via partial maxillectomy, lateral rhinotomy and craniotomy approaches. Postoperatively patients were treated with radiotherapy/chemotherapy based on the type of SRBCT.

Results

This study consists of 38 cases of SRBCT’s out of the 176 cases diagnosed with SNM between the age group of 0 to 80 years. Collected data was analysed. Out of the 38 patients included 22 (58%) were males and 16 (42%) were females with male to female ratio of 1.4:1. Majority 20 (53%) out of the 38 patients were between the age groups of 30 and 50 years with a mean age of presentation of 40 years. Youngest patient in our study was a 1 year old which was a case of rhabdomyosarcoma. Table 1 summarises the distribution of cases of SRBCT’s based on symptomatology, management, and histopathology findings including IHC. The most common symptom in our study was nasal obstruction which was seen in 26(68.4%) of the patients, followed by nasal discharge and anosmia in 14(36.8%) each, nasal mass in 12(31.5%), epistaxis, headache and facial swelling in 8(21%) each, telecanthus and proptosis each in 4(10.5%) of the patients. Based on the site of involvement the most common site involved was nasal cavity in 38(100%) followed by ethmoid sinus in 28(73.6%), maxillary sinus in 6(15.7%), sphenoid sinus in 2(0.05%) and nasopharynx in 4(1%) of the patients. Intracranial extension was seen in 16(4.2%) and orbital extension in 6(1.6%) of the patients. Table 2 summarises the imaging characteristics of each case. The various surgical procedures adapted in our study were endoscopic excision in 18(4.7%), endoscopic excision with PORT in 14(3.7%), Lateral rhinotomy with Partial maxillectomy with PORT in 4(1%) and Craniofacial resection 2(0.05%). 4 patients who underwent only endoscopic excision and 2 patients who underwent Lateral rhinotomy with Partial maxillectomy with PORT showed recurred on followup.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases of SRBCT’s based on symptomatology, management, and histopathology findings including IHC

| Type and Incidence SRBCT’s (n = 38) |

Symptomatology | Site of involvement | Treatment | IHC Positive markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Esthesioneuroblastoma (8) SRBCT’s (21%) SNM(4.5%) |

Nasal obstruction, blood stained nasal discharge, anosmia, telecanthus | Anterior skull base, ethmoid sinus, nasal cavity |

Endoscopic excision + Postoperative Radiotherapy (PORT) Craniofacial resection |

NSE, Synaptophysin, S-100 Chromogranin, neurofilaments |

|

Pituitary macroadenoma (7) SRBCT’s (18.4%) SNM(3.97%) |

Nasal obstruction, headache, anosmia, proptosis | Anterior cranial fossa, ethmoid sinus, nasal cavity | Endoscopic excision | Diagnosed with HPE |

|

Undifferentiated SCC (5) SRBCT’s (13.1%) SNM(2.8%) |

Cheek swelling, nasal obstruction, bloody nasal discharge | Maxillary sinus, nasal cavity | Partial maxillectomy + PORT | CK7, CK8, CK18 |

|

Craniopharyngioma(4) SRBCT’s (10.5%) SNC(2.27%) |

Nasal obstruction, headache, anosmia | Anterior cranial fossa, ethmoid sinus, nasal cavity | Endoscopic excison | Diagnosed with HPE |

|

Synovial sarcoma/ Spindle cell sarcoma (1) SRBCT’s (2.6%) SNM(0.57%) |

Nasal mass, nasal obstruction, anosmia | Anterior skull base, ethmoid sinus, nasal cavity | Endoscopic excision + PORT | STAT-6, S-100, TLE, BCL-2 |

|

Malignant melanoma (1) SRBCT’s (2.6%) SNM(0.57%) |

Black coloured nasal mass, nasal obstruction | Nasal cavity, nasopharynx | Endoscopic excision + PORT | S-100, HMB-45 |

|

Schwannoma (2) SRBCT’s(5.26%) SNM(1.13%) |

Nasal obstruction, nasal discharge | Anterior skull base, ethmoid sinus, sphenoid sinus | Endoscopic excison | S-100, CD56 |

|

Neuroendocrine Ca (2) SRBCT’s(5.26%) SNM(1.13%) |

Nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, anosmia | Anterior skull base, ethmoid sinus, nasal cavity | Endoscopic excision + PORT | NSE, Synaptophysin, Chromogranin, Ki-67 |

|

Lymphoma (2) SRBCT’s(5.26%) SNM(1.13%) |

Nasal obstruction, cheek swelling, submandibular swelling | Maxillary sinus | Endoscopic excision + submandibular lymph node excision + PORT | CD3, CD5 |

|

Rhabdomyosarcoma (2) SRBCT’s(5.26%) SNM(1.13%) |

Mouth breathing, bloody nasal discharge | Nasopharynx | Endoscopic excision | Diagnosed with HPE |

|

Neurofibroma (2) SRBCT’s(5.26%) SNM(1.13%) |

Nasal obstruction, anosmia | Anterior skull base, ethmoid sinus, nasal cavity | Endoscopic excision | S-100, CD34 |

|

Adenocarcinoma (1) SRBCT’s(2.6%) SNM(0.57%) |

Cheek swelling, nasal obstruction, bloody nasal discharge, proptosis | Anterior skull base, ethmoid sinus, orbit | Endoscopic excision | CK20, CDX2 |

Table 2.

Imaging Characteristics of various SRBCT’s

| Type of SRBCT’s | Plain CT | CECT | T1w MRI | T2w MRI | T1 w MRI with contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esthesioneuroblastoma | Homogeneous soft tissue hypoattenuation with bone erosion | Heterogeneous enhancement | Hypointense signal | Heterogeneous intermediate signal | Moderate enhancement |

| Pituitary macroadenoma | Homogenous soft tissue isointense to brain | Enhancement + | Heterogeneous intermediate signal | Heterogeneous intermediate signal | Bright enhancement |

| Undifferentiated SCC | Homogeneous soft tissue hypoattenuation with calcifications and bone erosion | Heterogeneous enhancement | Isointense signal | Hyperintense signal | Moderate enhancement |

|

Craniopharyngioma (adamantinomatous) |

Soft tissue density with cystic spaces | Heterogeneous enhancement | Hyperintense signal | Hyperintense signal | Enhancement + |

| Synovial sarcoma/ Spindle cell sarcoma | Soft tissue density with calcifications | Heterogeneous enhancement | Hypointense signal | Hypo to isointense signal | |

| Malignant melanoma | Homogeneous soft tissue hypoattenuation with bone erosion | Enhancement + | Homogeneous hypointense signal | Hypointense signal | Heterogeneous enhancement |

| Schwannoma | Homogeneous soft tissue density with adjacent bone remodelling | Mild enhancement | Isointense signal | Isointense signal | Strong enhancement |

| Neuroendocrine Ca | Isodense lesion with moth eaten bone destruction | Mild enhancement | Isointense signal | Mild hyperintense signal | Moderate enhancement |

| Lymphoma | Homogenous soft tissue isointense to muscle | Intermediate signal | Hypointense signal | Homogeneous enhancement | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Homogeneous soft tissue density with bone erosion | Mild enhancement | Low to intermediate intensity | Hyperintense signal | Strong enhancement |

| Neurofibroma | Well defined hypodense mass | No enhancement | Hypointense signal | Hyperintense signal | Heterogeneous enhancement |

| Adenocarcinoma | Homogeneous soft tissue density with bone erosion | Heterogeneous enhancement | Intermediate signal | Intermediate signal | Heterogeneous enhancement |

Discussion

Small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal area are extremely rare but includes a wide variety of both benign and malignant neoplasms.3 The SRBCT’s constitute a heterogeneous group of malignant neoplasms that are characterized by a monotonous population of undifferentiated tumor cells with relatively small sized nuclei and scanty cytoplasm [4]. An early and an accurate diagnosis is imperative to allow a patient with SRBCT to undergo appropriate therapy.

In our study, among 176 cases diagnosed with SNM, 38 (21.6%) cases were diagnosed with SRBCT’s which was much lesser when compared to the study conducted by Das et al., who reported 34.6% of SRBCT’s in their sample size of 81 patients [5]. Our study showed male preponderance with male to female ratio of 1.4:1. Majority 20 (53%) out of the 38 patients were between the age groups of 30 and 50 years. The mean age of presentation was 40 years.

Most common symptom among all the cases was nasal obstruction which was complained by 26 (68%) of the patients followed by nasal discharge and anosmia each in 14(37%) patients. Other symptoms were epistaxis, headache, nasal mass, cheek swelling, telecanthus and proptosis. All the cases had nasal cavity involvement followed by ethmoid sinus in 28 (74%) patients. Intracranial involvement was noted in 8(42%) patients and orbital involvement with breach of lamina papyracea in 3(16%) patients.

Most common histopathological type among all the SRBCT that presented to us was esthesioneuroblastoma i.e., 8 (21%). Esthenioneuroblastoma (ENB) is an uncommon SNM with the tumor arising from the basal cells of the olfactory neuroepithelium and is confined to the upper nasal cavity in the region of the cribriform plate [6, 7]. They are locally aggressive metastatic tumors. The most widespread classification system for ENB was first proposed by Kadish et al. in 1976 [8]. Our study reported 4.5% of the total 176 cases of SNM, which was similar to the data reported in literature of 1 to 5% of SNM [9]. On HPE the charachterisctics of ENB include nests of SRBCT with the presence of fibrillary cell processes, Homer Wright rosettes, and S100-positive sustentacular cells which were similar findings in our study [6, 10]. The management of ENB consists of a combination of surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The overall survival, for all ENB patients has been reported to be about 76% [11].

According to our study the next most common SRBCT, was pituitary macroadenoma 7(8.4%) and 3.97% of SNM which was almost similar to the reported literature of less than 3% of SNM. HPE is charachteristic of SRBCT which are chromophobic cells with moderate to abundant cytoplasm with uniform nuclear morphology with stippled chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli.

Lymphomas are uncommon malignancies of the sinonasal tract and constitute only 1.5% of all lymphomas. The most common age of presentation has been reported to be during 4th and 5th decade of life [12, 13]. Our study reported 3(7.9%) of SRBCT and 1.7% of SNM. This was very less compared to the reported literature. Necrosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and vascular invasion are common. Demonstration of the Ebstein Barr virus (EBV) by in situ hybridization for EBV encoded early RNA’s in addition to a NK-cell with IHC positive markers (CD2+, CD56+, CD43+, CD3e+, granzyme B + and perforin positive) is indicative of this malignancy.4 Chemotherapy is considered to be the treatment of choice.

Sinonasal undifferentiated cell carcinoma (SNUC) is a rare highly aggressive tumor with male preponderance with male to female ratio of 2–3:1 [14] and this mainly arises from nose and PNS area, with early spread into the orbit and intracranially [15]. It is seen comprising 3–5% of all SNM. This was similar to our study constituting 2.8% of all SNM [15, 16]. The usual age of presentation ranges between 3rd to 9th decade. Frierson et al. described this malignancy for the first time in 1986, and it was believed to originate from the Schneiderian epithelium of the nose and PNS [17, 18]. They appear as fungating mass with poorly defined margins with extension into adjacent structures. HPE is characterised by SRBCT, with lymphovascular and neural invasion. With the use of a panel of IHC markers, positive staining for neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin, cytokeratins 7, 8 and 19 and nonreactivity to S-100 and non-expression of vimentin suggest this tumor is of epithelial origin [19, 20]. Surgery with craniofacial resection followed by radiation or chemoradiation therapy is considered the standard treatment for SNUC. The prognosis of these tumors is extremely poor.

Craniopharyngiomas are benign but aggressive epithelial tumors usually originating in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland from squamous remnants of an incompletely involuted craniopharingeal duct developing from the Rathke pouch. They constitute about 1% all central nervous system tumors but may increase upto 4% in paediatric age group [21]. According to our study they constitute about 8(10.5%) of SRBCT. The tumor characteristics are solid (with or without calcification) and may be cystic also. The cyst is filled with a turbid, brownish yellow coloured proteinaceous material with high content of cholesterol crystals. Surgical excision, with or without adjuvant conventional external beam irradiation, is the primary option for treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Fahlbusch [22] and colleagues showed 86.9% of recurrence free survival at 5 years and 81.3% at 10 years.

Rhabdomyosarcomas are rare malignancies that account for a small fraction of all head and neck tumors, presenting in 0.041 per 100,000 patients per year [23]. They constitute about 50% of paediatric soft tissue sarcomas. Our study reported 2(5.6%) of SRBCT and 1.13% of SNM. Head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma includes various histologic subtypes, such as alveolar, embryonal, pleomorphic, and mixed. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft tissue malignancy in children and often metastasises to cervical lymph nodes and the lung [24]. The mainstay of treatment is a combination of multiagent chemotherapy and radiotherapy [25].

Sinonasal malignant mucosal melanoma is a rare, aggressive and a capricious tumour. According to our study they constituted about 2.6% of SRBCT and 0.57% of SNM, which was less when compared to the reported literature of 4% [26]. They are grossly polypoidal and most of them demonstrate a brown or black pigmented surface. IHC is necessary to confirm the diagnosis by demonstrating protein S100, VIM, HMB-45, melan-A, tyrosinase, and MITF (microphthalmia transcription factor), in addition to the presence of intracellular melanin itself. SOX10 is a newer marker, with high sensitivity for mucosal melanoma (88–100%) [27, 28]. Surgical excision in combination with postoperative radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy is considered to be the mainstay of treatment. There are very few published series, but all authors report poor outcomes irrespective of treatment. The 5 year survival approximately is 25% .

Synovial sarcoma are extremely rare in the sinonasal area. The head and neck region is the second most common site of involvement for synovial sarcoma, although cases arising in the sinonasal tract are rare [29]. Very few cases have been previously reported in literature. According to our study they constitute about 2.6% of SRBCT’s and 0.57% of SNM. IHC helps in diagnosis, and shows positivity to cytokeratin, EMA, BCL2, and TLE1. Ctyogenetic FISH, or molecular confirmation of the t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) or derived SYT-SSX chimeric transcripts facilitates an absolute diagnosis. Surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy with ifosfamide is considered treatment of choice.

Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma is a high grade neoplasm that most frequently arises in the superior or posterior part of the nasal cavity. Our study reported 2(5.6%) of SRBCT’s and 1.13% of SNM. These tumors are composed of small to intermediate sized cells with oval or round hyperchromatic nuclei with absent or inconspicuous nucleoli. The tumor cells may be arranged in sheets, nests, and trabeculae and often exhibit extensive apoptosis, necrosis, and hemorrhage. Most are positive for cytokeratin and may show punctate perinuclear positivity which is typical of small cell carcinomas arising in other locations [30]. CD56 staining is common whereas staining for synaptophysin, chromogranin and NSE is variable [15]. In our study, other tumors rarely seen are intestinal type adenocarcinoma about 1(2.6%) of SRBCT’s. Schwannoma’s and neurofibroma’s about 2 (5.2%) each of total SRBCT’s.

Based on the management, in our study, endoscopic complete excision alone was performed in 18 (47%) patients. Endoscopic excision with PORT was performed in 16 (42%) patients. Lateral rhinotomy with partial maxillectomy with PORT was performed in 4(10%) cases of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. 2 (5%) cases of esthesioneuroblastoma underwent craniofacial resection. In total, 6 (16%) patients presented with recurrence which included malignant melanoma, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma and synovial/spindle cell sarcoma. Of 16 cases, 4(10%) cases of recurrence occurred following endoscopic excision.

Conclusion

Sinonasal SRBCTs are extremely rare tumors seen in the nose and PNS region. Accurate classification of these diverse sinonasal SRBCTs is essential and may be challenging due to overlapping clinical, radioglogical and HPE features. Advances in IHC and molecular genetics have greatly helped in diagnoses of these tumors. Histopathological diagnosis with IHC is charachteristic of various tumors and is conclusive for diagnosis. Knowledge of this tumor entity is essential for a precise and an early diagnosis which helps in planning appropriate management in preventing spread to vital structures and improving outcome. Most of the tumors have a multimodality treatment approach which includes surgical excision, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge and thank medical supernindent, faculty, postgraduates, patients and attendants for accepting for publication.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WatkinsonJC,ClarkeRW,(2018)Scott-Brown’s Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck surgery: 3 volume set.CRC Press;Jul17.

- 3.Thompson LD. Small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal tract: a differential diagnosis approach. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(s1):S1-S26. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridge JA, Bowen JM, Smith RB. The small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal area. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4(1):84–93. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das R, Sarma A, Sharma JD, Singh D, Rahman T, Kataki AC. Clinico-histopathological study of sinonasal malignant tumours - a 5 years experience at a tertiary cancer institute. Headache. 2018;6(11):48–59. doi: 10.18535/jmscr/v6i11.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen ZR, Marmor E, Fuller GN, DeMonte F. Misdiagnosis of olfactory neuroblastoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(5):e3. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.12.5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills SE, Frierson HF., Jr Olfactory neuroblastoma. A clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9(5):317–327. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC. Olfactory neuroblastoma. A clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976;37(3):1571–1576. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3<1571::aid-cncr2820370347>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iezzoni JC, Mills SE (2005). “Undifferentiated” small round cell tumors of the sinonasal tract: differential diagnosis update. Am J Clin Pathol. 124 Suppl:S110-S121. 10.1309/59RBT2RK6LQE4YHB. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wenig BM. Undifferentiated malignant neoplasms of the sinonasal tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(5):699–712. doi: 10.5858/133.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey RM, Godovchik J, Workman AD. Patient, disease, and treatment factors associated with overall survival in esthesioneuroblastoma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(12):1186–1194. doi: 10.1002/alr.22027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncavage JA, Campbell BH, Hanson GA. Diagnosis of malignant lymphomas of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx. Laryngoscope. 1983;93(10):1276–1280. doi: 10.1002/lary.1983.93.10.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fajardo-dolci G, Magaña RC, Bautista EL, Huerta D. Sinonasallymphoma (1999).Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.121(3):323–326. 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70192-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fletcher CD (2019) Diagnostic histopathology of tumors E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- 15.Thompson L. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85(2):74. doi: 10.1177/014556130608500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goel R, Ramalingam K, Ramani P, Chandrasekar T. Sino nasal undifferentiated carcinoma:a rare entity. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2012;3(1):101–104. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.95986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frierson HF, Jr, Mills SE, Fechner RE, Taxy JB, Levine PA. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. An aggressive neoplasm derived from schneiderian epithelium and distinct from olfactory neuroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10(11):771–779. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarangi S, Khera S, Vishwajeet V, Meshram V, Setia P, Malik A. A rare presentation of Sinonasal Undifferentiated Carcinoma with brain metastasis and para-aortic mass. Autops Case Rep. 2020;10(4):e2020222. doi: 10.4322/acr.2020.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ejaz A, Wenig BM. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: clinical and pathologic features and a discussion on classification, cellular differentiation, and differential diagnosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12(3):134–143. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000163958.29032.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeng YM, Sung MT, Fang CL. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma and nasopharyngeal-type undifferentiated carcinoma: two clinically, biologically, and histopathologically distinct entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(3):371–376. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.RichardG.Ellenbogen,Laligam N.Sekhar,Neil D.Kitchen,Harley Brito da Silva (2018)(4th eds) Craniopharyngiomas. Principles of neurological surgery,Elsevier,Pages 204–218.e3,<background-color:#CFBFB1;udirection:rtl;>https://doi.org/10.1016</background-color:#CFBFB1;udirection:rtl;> B978-0-323- 43140-8.00012-3.

- 22.Fahlbusch R, Honegger J, Paulus W, Huk W, Buchfelder M. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(2):237–250. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.2.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MH, Atherton D, Reith JD, Islam NM, Bhattacharyya I, Cohen DM. Rhabdomyosarcoma, Spindle Cell/Sclerosing variant: a clinical and histopathological examination of this rare variant with three new cases from the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(4):494–500. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0818-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallego Melcón S, Sánchez de Toledo Codina J. Rhabdomyosarcoma: present and future perspectives in diagnosis and treatment. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7(1):35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02710026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parham DM, Barr FG. Classification of rhabdomyosarcoma and its molecular basis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(6):387–397. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a92d0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno MA, Roberts DB, Kupferman ME. Mucosal melanoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses, a contemporary experience from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer. 2010;116(9):2215–2223. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams MD. Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization classification of Head and Neck Tumours: mucosal melanomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(1):110–117. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0789-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xavier Júnior JCC, Ocanha-Xavier JP. What does the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of Head and Neck Tumors bring new about mucosal melanomas? An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(2):259–260. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallia GL, Sciubba DM, Hann CL. Synovial sarcoma of the frontal sinus. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(6):1077–1080. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Ordonez B, Caruana SM, Huvos AG, Shah JP. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(8):826–832. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]