Abstract

Dislodgement of surgical sponge into airway during the intraoperative period is uncommon as the airway, in most cases secured by an endotracheal tube. We report such an unusual case during micro laryngeal surgery and direct laryngoscopy assessment under general anaesthesia. This shows early suspicion and quick action to avoid disaster.

Keywords: Surgical sponge, Airway, Anaesthesia

Introduction

Micro laryngeal surgeries (MLS) are being increasingly performed for diagnosing and treating laryngeal pathologies. These surgeries present an anaesthetic challenge that requires the simultaneous control of the airway, maintenance of gas exchange, and good surgical exposure. Therefore, good communication between anaesthetists and surgeons is necessary to prevent catastrophic complications [1]. Some known complications during MLS include difficult intubation, inadequate depth of anaesthesia, loss of airway, laryngospasm, cuff rupture. In this article, we report an unusual event during MLS surgery and its management. The patient has provided written consent to publish this case report.

Case Report

A 53-year-old male patient presented to the outpatient department of our hospital with the complaint of hoarseness of voice for one year, which was insidious in onset and gradually progressive. He denied any history of cough, blood in sputum, weight loss, difficulty in swallowing, respiratory distress, or stridor-like symptoms. He was further evaluated for hoarseness of voice. Indirect laryngoscopy was done, which showed bilateral mobile vocal cords and ulcerated lesion over posterior 1/3rd of the left true vocal cord and inter arytenoid area. Computed tomography showed soft tissue thickening with nodularity (8 × 4 mm) along the left true vocal cord with a mild luminal bulge. Subsequently, he was posted for direct laryngoscopy (DL) assessment and micro laryngeal surgery (MLS) for further management.

After a thorough preoperative evaluation and confirming fasting as per standard institution protocol, the patient was taken to the operation theatre. All standard monitoring, including electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure, was attached. Anaesthesia was induced with intravenous fentanyl and propofol. After achieving adequate muscle relaxation with atracurium, the patient was intubated with a cuffed micro laryngeal tube (MLT) (5.0 mm ID) and fixed at 21 cm. MLS tube is a small diameter single-lumen endotracheal tube (ETT) used for micro laryngeal surgeries as it offers more working space for surgeons. These tubes have low pressure, large volume, and large diameter cuff to protect the airway [2, 3].

After DL assessment, multiple punch biopsy specimen was taken from growth. During mid-surgery, there was a sudden desaturation followed by loss of capnographic waveforms. Oxygen saturation fell from 100 to 90%. On detailed examination of the breathing circuit and MLS tube, we found the deflated pilot balloon, which was not inflated with further air instillation. Suspecting MLS cuff rupture, surgeons were cleared from the field. The fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was increased to 100%, and the patient was then re-intubated with a new MLS ETT of 5.0 mm ID.

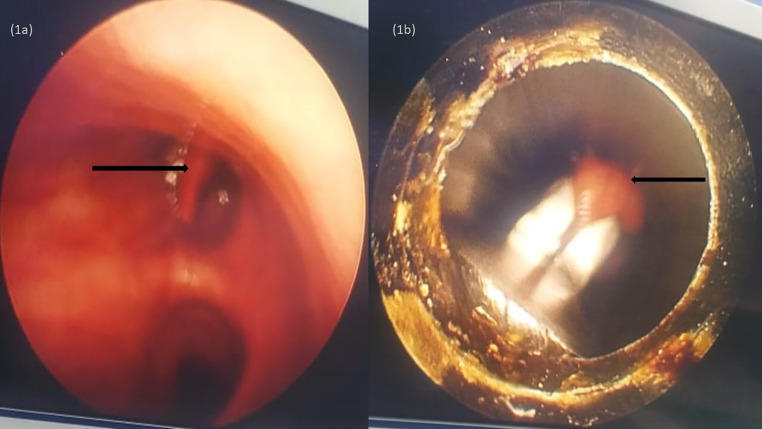

Towards the end of the procedure, the surgical team noticed a missing surgical sponge (hydrophilic non-woven cotton material measuring 9 cm x 1.5 cm) kept near the left vocal cord. The staff did re-counting of the surgical sponges, and the surgeons did the proper oropharyngeal examination with C-MAC® (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) video laryngoscope. After a thorough inspection of the oropharynx and nasopharynx, surgeons then suspected that the surgical patty might have dislodged into the trachea during re-intubation. The anaesthetic team then did fiber optic bronchoscopy (FOB) after deflating the MLS tube cuff. On FOB, the missing surgical sponge was localized near the left mainstem bronchus(Fig. 1a). A rigid bronchoscope was then introduced after the withdrawal of the MLS tube. Subsequently, the surgical sponge was retrieved from the left mainstem bronchus with the help of artery forceps (Fig. 1b). The patient was shifted to the post anaesthesia care unit after extubation without any respiratory complications. He was subsequently followed in the ward and did not have any fresh complaints.

Fig. 1.

1a: Fiberoptic bronchoscopy showing surgical sponge in left main bronchus; 1b: Retrieval of the surgical sponge by rigid bronchoscope

Discussion

A surgical sponge dislodged into the patient’s airway under anaesthesia is an uncommon but serious complication. This case report details the actions that transpired to recover the dislodged surgical sponge successfully.

A foreign body lodged in the tracheobronchial tree may be a potentially fatal situation that often needs prompt attention. Foreign substances retained in the body may cause both acute and chronic inflammatory responses. Although surgical sponges are usually composed of inert cotton, they may cause an aseptic reaction characterized by granuloma, fibrosis, adhesions, calcification, and ulceration. Additionally, they may become infected, resulting in the development of abscesses and fistulization to neighbouring structures [4]. Displacement of a surgical sponge into the distal airways may result in submucosal tunnelling, airway blockage, atelectasis, airway trauma/bleeding, increased work of breathing, hypoxemia, and death. If left untreated, it might have resulted in a disastrous scenario. They are known as textiloma or gossypiboma [5].

Tabuena et al. described a case in which a surgical gauze was being left in the mediastinum for 21 years after surgery and migrating into the trachea through the tracheal wall [6]. Similarly, Szentmariay et al. described a sudden death due to asphyxia caused by a surgical sponge retained after a 23-year-old thoracic surgery [7]. Haddad et al. reported a case of a surgical sponge left unintentionally in the mediastinum during a difficult mediastinoscopy migrating into the trachea six years later, causing airway obstruction [8].

In our case, the surgical, nursing, and anaesthesia teams collaborated to avoid serious complications that might have happened due to a retained surgical sponge. This demonstrates the need to exercise additional caution in ensuring that the surgical team performs accurate counts. Toward the end of the procedure, the surgeon and surgical assistants are accountable for counting the gauzes used throughout the operation. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) checklist should be included in institutional policies to enhance surgical safety and patient care [9].

Conclusion

Adult patients undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia may aspirate a foreign body. The consequences caused by a retained foreign body may be severe, even deadly. A thorough examination of the surgery site and meticulous counting of surgical sponges are critical. It is the surgical and anaesthetic teams’ joint responsibility to ensure the safety of every patient admitted to the operating room’s doors.

Acknowledgements

None. This manuscript is approved by all the authors.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the article. Ankur Sharma, MD. This author helped review the literature, write the discussion and correct the manuscript. Naina Chandnani, DNB. This author helped write the introduction and case presentation part of the manuscript. Navin Vincent, MBBS. This author helped write the introduction and case presentation part of the manuscript. Shilpa Goyal, MD. Contribution: This author helped write the discussion. *Patient consent has been obtained for publication of this case report.

Grant/Funding

None.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared.

Patient Consent

Obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ankur Sharma, Email: ankuranaesthesia@gmail.com.

Naina Chandnani, Email: Chandnaninaina25@gmail.com.

Navin Vincent, Email: navincentp@gmail.com.

Shilpa Goyal, Email: drshilpagoyal@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Hsu J, Tan M. Anesthesia considerations in laryngeal surgery. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;55:11–32. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt J, Günther F, Weber J, Kehm V, Pfeiffer J, Becker C, Wenzel C, Borgmann S, Wirth S, Schumann S. Glottic visibility for laryngeal surgery: Tritube vs microlaryngeal tube: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36:963–971. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha R, Trikha A, Subramanian R. Microlaryngeal endotracheal tube for lung isolation in pediatric patient with significant tracheal narrowing. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:490–493. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.215427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patial T, Rathore N, Thakur A, Thakur D, Sharma K. Transmigration of a retained surgical sponge: a case report. Patient Saf Surg. 2018;12:21. doi: 10.1186/s13037-018-0168-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HS, Chung TS, Suh SH, Kim SY. MR imaging findings of paravertebral gossypiboma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:709–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabuena RP, Zuccatosta L, Tubaldi A, Gasparini S. An unusual iatrogenic foreign body (surgical gauze) in the trachea. Respiration. 2008;75:105–108. doi: 10.1159/000088691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szentmariay IF, Laszik A, Sotonyi P. Sudden suffocation by surgical sponge retained after a 23-year-old thoracic surgery. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004;25:324–326. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000137273.73799.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddad R, Judice LF, Chibante A, Ferraz D. Migration of surgical sponge retained at mediastinoscopy into the trachea. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2004;3:637–640. doi: 10.1016/j.icvts.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haugen AS, Sevdalis N, Søfteland E. Impact of the World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist on Patient Safety. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:420–425. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]