Abstract

The incidence of sensorineural hearing loss is between 1 and 3 per 1000 in healthy neonates and 2–4 per 100 in high-risk infants. In this study, we assessed the incidence of hearing impairment in normal term (≥ 37 wga) infants (control group), in children with suspicion and/or risk factors of hearing loss, included premature infants (< 37 weeks gestational age (wga) and/or low birth weight < 2,5 Kgr), in children diagnosed with a specific syndrome and in children with speech disorder, candidate for speech therapy. Hearing impairment is a severe consequence of prematurity and its prevalence is inversely related to the maturity of the baby based on gestation age and /or birth weight. Both above parameters are of particular importance and it has not been found that one factor prevails over the other. Premature infants have many concomitant risk factors for hearing impairment. The most important other risk factors were ototoxic medications, very low birth weight and “treatment in the intensive care unit ‘’ (low Apgar score and mechanical ventilation). Frequent risk factors such as congenital infections and family history of hearing loss, although frequently recorded, does not seem to be very significant. Children with speech disorder do not seem to suffer from hearing impairment more frequently than children in general population.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Prematurity, Risk factors, Otoacoustic emissions, Auditory brainstem response

Introduction

The incidence of sensorineural hearing loss is between 1 and 3 per 1000 in healthy neonates and 2–4 per 100 in high-risk infants [1].

In order to achieve effective treatment, congenital or perinatal hearing loss should be recognised within three months of life, with confirmative audiological diagnosis and early intervention before the 6th month of age. [2] Early treatment is essential, as the first year of life is critical for normal development of speech and language, as well as intellectual and emotional growth [3, 9].Children with untreated hearing loss may have delayed or limited speech and language development as they age.

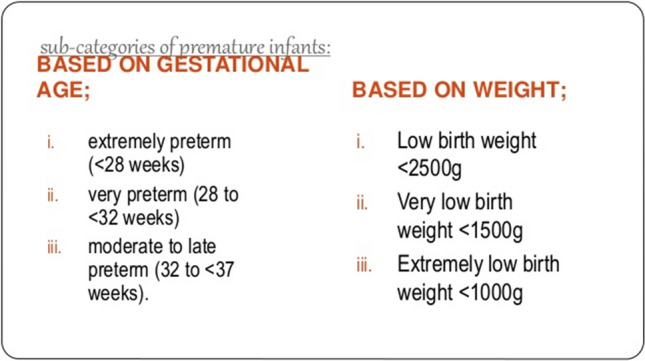

Premature infants are 50% more likely than normal term infants to develop hearing loss [3, 4]. There are two sub-categories of premature infants based on gestational age and based on birth weight (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sub-categories of premature infants

Patients and Methods

In this study, we assessed the incidence of hearing impairment in normal term (≥ 37 wga) infants (control group), in children with suspicion and/or risk factors of hearing loss, included premature infants (< 37 weeks gestational age (wga) and /or low birth weight < 2,5 Kgr), in children diagnosed with a specific syndrome and in children with speech disorder, candidate for speech therapy. All premature infants (< 37 weeks gestational age (wga) and /or low birth weight (< 2,5 Kgr) were treated as infants with risk factors due to their prematurity.

We reviewed retrospectively the audiological charts of all children (n = 448) who were admitted to the Audiology Department of our hospital between 2014 and 2020. All children had none /one or more risk factors for hearing loss, as they have been defined and modified by the American Joint Committee on Infant Hearing during the study years [5–8].

Audiologic evaluation included history taking, otoscopy, tympanogram and screening with TOAEs (Transient Otoacoustic Emissions).

ABR (Auditory Brainstem Response) testing under natural or chloral hydrate-induced sleep were also performed in all neonates and infants with abnormal TOAEs responses and /or had risk factors. Especially preterm infants, with an increased risk for SNHL and auditory neuropathy spectrum disorders, are screened with auditory brainstem response (ABR) [9].

Results

We analyzed the incidence of different types and intensity of hearing deficits in relation to gestational age and gestational weight.

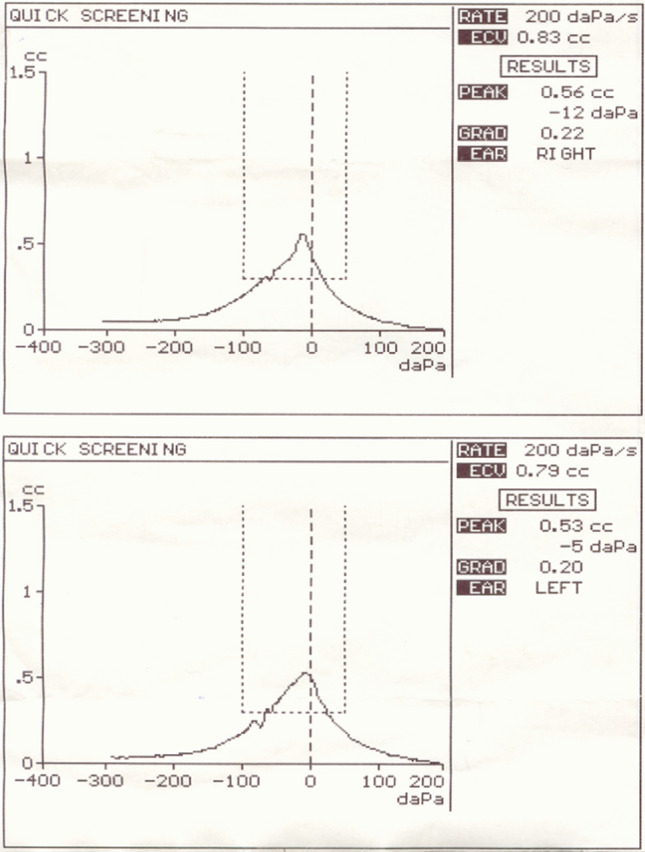

For the evaluation of hearing threshold all the examined children had tympanogram type A bilaterally (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Normal tympanogram type A bilaterally

The mean time of the final diagnosis in all groups of children was the 120th day of life.

63% of all tested children were normal term (≥ 37 wga), 21% (n = 94) were preterm, 4% had at least one other risk factor for hearing loss except prematurity (ototoxic medications, prolonged respirator care in intensive care unit, high serum bilirubin concentration, family history of hearing loss, craniofacial anomalies, congenital infections), 2% were diagnosed with a specific syndrome and 10% were candidate for speech therapy.

Hearing deficit was diagnosed in 6% of all the examined children.

78% among the children with hearing deficit were males and 22% females.

Hearing deficit was diagnosed in 9% of all preterm (n = 94) infants.

75% of the preterm children (n = 94) were males and 25% females.

Hearing screening was positive for hearing impairment in 19% at extremely preterm infants < 28 wga in 5,5% at very preterm infants 28 to < 32 wga and in 3% at moderate to late preterm infants 32 to < 37 wga.

Hearing screening was positive for hearing impairment in 18% of extremely low birth weight preterm infants (< 1Kgr), in 7,5% at very low birth weight preterm infants (< 1,5 Kgr) and in 2% at low birth weight preterm infants (< 2,5 Kgr).

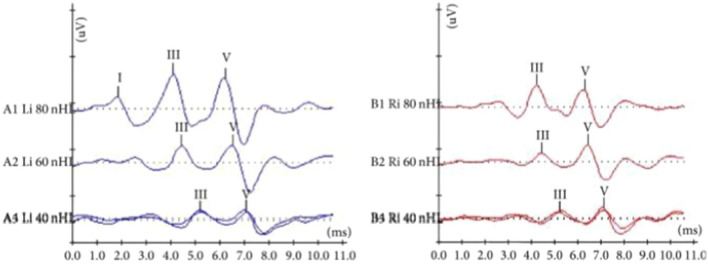

Hearing screening was positive for hearing impairment in < 1% in normal term (≥ 37 wga) infants (control group). In most such cases typical and replicable ABR waveforms were elicited at 60 and 40 dBnHL bilaterally (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Typical and replicable ABR waveforms were elicited at 60 and 40 dBnHL bilaterally

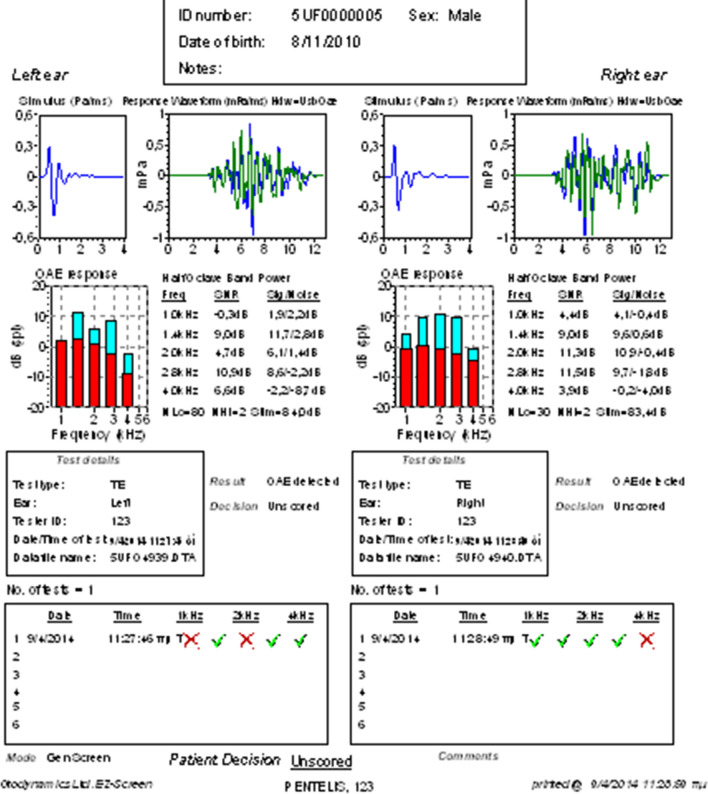

Based on gestational age, the most serious problem–permanent profound sensorineural unilateral and /or bilateral hearing deficit (90 dB) was diagnosed in 12.4% of extremely preterm infants < 28 wga, in 5% at very preterm infants 28 to < 32 wga and in 0.2% at moderate to late preterm infants 32 to < 37 wga) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

ABR waveforms were obtained at 90 dBnHL on the left and 80 dBnHL on the right ear

Based on gestational weight, the most serious problem–permanent profound sensorineural unilateral and /or bilateral hearing deficit ( 90 dB) was diagnosed in 17.7% of extremely low birth weight preterm infants (< 1Kgr), in 3% at very low birth weight preterm infants (< 1.5 Kgr), in 0.8% at low birth weight preterm infants (< 2.5 Kgr) (Fig. 4).

All above results were statistically significant (p value < 0.05).

Thus, the final diagnosis of hearing impairment was given predominantly in extremely preterm infants born < 28 weeks of gestation − 19% and in extremely low birth weight preterm infants (< 1Kgr) − 18%.

Hearing deficit was diagnosed in 9% of children with other risk factors for hearing loss, except prematurity.

The most important other risk factors were ototoxic medications, very low birth weight and “treatment in the intensive care unit (low Apgar score and mechanical ventilation).

Risk factors of hearing deficit were found in 4% of all tested infants. All premature infants (born < 37 wga) were treated as infants with risk factors due to their prematurity. At least one other risk factor was identified in 85% of them. Most frequent risk factor was exposure to “ototoxic medications”, accounting for 63% in this population. The second and the third most frequent risk factors were “low birth weight < 2,5 Kgr”– 54% and “treatment in the intensive care unit”– 42%.

Other significant frequent risk factors were congenital infections 5% and family history of hearing loss 3%, however their frequency in normal term (control group) infants was comparable to preterm infants (< 37 wga) and was not significant (p value < 0,05).

Hearing impairment was diagnosed in 2% of syndromic children.

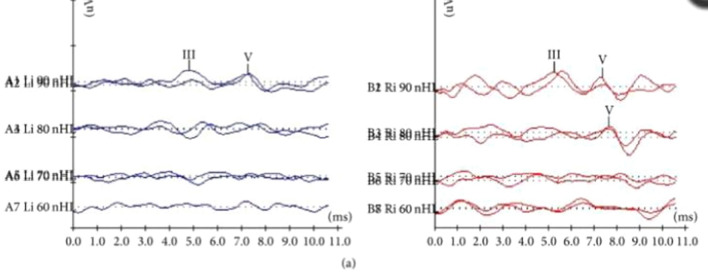

On the contrary, only < 1% among children candidate for speech therapy had hearing loss. In the rest of those children normal otoacoustic emissions were obtained bilaterally (Fig. 5). It is noteworthy that almost 75% of the children who were candidates for speech therapy were children who belonged to the autism spectrum. The frequency of hearing impairment in children with speech disorder was comparable to general population and was not statistically significant (p value > 0.01).Thus, hearing impairment in children with speech disorder, does not seem to be the etiological factor of their disorder and they are candidate for speech therapy due to other reasons.

Fig. 5.

Normal otoacoustic emissions were obtained bilaterally

Conclusions

The diagnosis of sensorineural hearing loss should be done as early as possible. This can only be achieved through unified tracking and recording protocols for all births nationwidely. Diagnosis is achieved by crossing all available techniques (Tympanometry, OAEs, ABR).

Although OAEs appear to be the most appropriate screening test method for normal full-term neonates, the combination of OAES with A-ABR is considered ideal for early detection and diagnosis of congenital hearing loss and Auditory Neuropathy—Dysynchrony in high risk newborns.

Monitoring of high risk infants for at least the first 3 years of life is necessary.

In the investigation of the bilateral prelingual hearing loss the 35delG mutation should be detected due to its large impact on the general population.

Hearing impairment is a severe consequence of prematurity and its prevalence is inversely related to the maturity of the baby based on gestation age and /or birth weight. Both above parameters (age and weight) are of particular importance and it has not been found that one factor prevails over the other.

Premature infants have many concomitant risk factors for hearing impairment which influence the occurrence and the intensity of hearing deficit. The most important other risk factors were ototoxic medications, very low birth weight and “treatment in the intensive care unit ‘’ (low Apgar score and mechanical ventilation).

Other frequent risk factors e.g. congenital infections and family history of hearing loss, although frequently recorded, does not seem to be very significant.

Children with speech disorder do not seem to suffer from hearing impairment more frequently than children in general population. They are candidate for speech therapy due to other reasons.

Abbreviations

- ABR

Auditory brainstem response

- OAEs

Otoacoustic emissions

Author Contributions

All authors read, critiqued and approved the manuscript revisions as well as the final version of the manuscript. Also, all authors participated in a session to discuss the results and consider strategies for analysis and interpretation of the data before the final data analysis was performed and the manuscript written. All authors are part of the team managing the cases and approved the final version of the document.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

There is an ethical approval for this publication.

Consent to Participate

All patient’s parents consent for participation.

Consent for Publication

All patient’s parents consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kang MY, Jeong SW, Kim LS. Changes in the hearing thresholds of infants who failed the newborn hearing screening test and in infants treated in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;5(Suppl 1):S32–S36. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2012.5.S1.S32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.JCHI Joint Committee of Infant Hearing Position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2019;4(2):1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moeller MP. Early intervention and language development in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):e43–e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polinski C. Hearing outcomes in the neonatal intensive care Unit Graduate. Newborn Infant Nursing Rev. 2003;3(3):99–103. doi: 10.1016/S1527-3369(03)00037-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Joint committee on infant hearing 1994 position statement. Pediatrics. 1995;95(1):152–156. doi: 10.1542/peds.95.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Position statement. Am Speech Lang Hearing Association. 1994;36(12):38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Am J Audiol. 2000;9(1):9–29. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2000/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):898–921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzzetta F, Conti G, Mercuri E. Auditory processing in infancy: do early abnormalities predict disorders of language and cognitive development? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:1085–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]