Abstract

Introduction: Malignancies in children are different from those found in adults and are a significant cause of childhood mortality.They have varied clinical presentation depending on site and type of disease.It is essential to recognize the early signs and symptoms of malignancies in childhood, especially those involving head and neck region, so as to reduce childhood mortality and morbidity. Materials: A total of 2384 children were admitted over a period of 7 years. Out of these, 1004 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were chosen for further evaluation.They were thoroughly evaluated by undertaking a detailed history and clinical examination.Whenever required, additional investigations were performed.After carrying out the necessary investigations, the cases were accordingly managed. Data was evaluated using proper statistical tools. Results: Out of 1004 cases fulfilling the inclusion criteria, 42 turned out to be malignant, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.2. Malignancies in children were more common in the age group of 11–18 years, followed by 1–5 years,6–10 years and 0–1 years,with rates of 59.5%, 21.4%, 16.7% and 2.4% respectively. A wide variety of tumour types were recorded,e.g.,Hodgkin’s lymphoma,non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,acute leukemia,papillary carcinoma thyroid, nasopharyngeal carcinoma,Langerhans cell histiocytosis,rhabdomyosarcoma, olfactory neuroblastoma and salivary gland neoplasm. Conclusion: Incidence of head and neck tumors in pediatric age group was found to be 1.76% with lymphoma being the most frequent.Commonest age of presentation was above 10 years. There was an overall female predominance with a male:female ratio of 1:1.2. Awareness of a potential malignancy and careful follow-up of children with suspicious head and neck cancers is mandatory for early diagnosis and prompt treatment.

Keywords: Childhood malignancy, Head and neck cancer, Lymphoma

Introduction

Worldwide, approximately 300,000 children aged 0–19 years are diagnosed with cancer each year, of which approximately 96,000/year succumb to their illness [1]. The frequency of malignancy-related deaths amongst children aged more than 5 years is second only to accidental trauma [2]. An estimated 12% of childhood malignancies involve the head and neck region and 5% of primary malignant tumours in children originate in this region [3, 4]. It is essential for the otorhinolaryngologist treating children to have knowledge of malignancies occurring in childhood, as neck masses often provide a diagnostic dilemma to the primary care physician.Out of every 4 childhood malignancies,1 will eventually involve the head and neck region.It is essential to recognize the early signs and symptoms of malignancies in childhood, especially those involving head and neck region, so as to reduce childhood mortality and morbidity.

This study is a modest attempt to discuss the clinical presentations of various childhood malignancies encountered during the practice of Otorhinolaryngology at our Institute, to identify the features separating them from other benign conditions and to focus on current management strategies and new developments as they relate to the role of the otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon.

Aims and Objectives

Thorough knowledge of the clinical presentations of different childhood malignancies of the head and neck region is essential during day-to-day practice of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. This will help in establishing a proper diagnosis and in the treatment plan.

Materials and Methods

After approval by the Institutional Ethical Committee,the study was conducted over a 7-years period under the aegis of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, Guwahati, Assam. India. Children between the age group 0–18 years with clinical presentation of any one of the following were included in the study:

Cervical lymphadenopathy.

Any unusual lump/swelling in neck and in other parts of the body.

Easy bruising.

Repeated nasal bleeding.

Unexplained ear bleed.

Persistent earache with discharge,after usual treatment for chronic otitis media,serous otitis media and impacted ear wax.

Frequent headache with/without vomiting.

Sudden unexplained weight loss.

Unexplained pallor and weakness.

Unexplained fever/illness that does not respond to usual treatment.

Unresolved oral ulceration.

Primarily intracranial and intraorbital cancers were excluded from the study.

Methodology

This study included data from the out-patient,emergency,in-hospital admission and the operation registers maintained at the Otorhinolaryngology department.Patients were assessed clinically and their case-files studied to understand the case report thoroughly.The main outcome measures were the age-sex distribution and diagnosis of paediatric head and neck cancer.After clinical assessment,a fine needle aspiration cytology and/or biopsy for histopathological study was done in all cases for a confirmed pathological diagnosis.Blood tests including complete haemogram,endoscopic procedures,investigations like X-ray,computerised tomographic(CT) scans,and magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) of head and neck region were also done as required to arrive at the diagnosis.All the histologically confirmed cases were followed by interventions according to standard clinical protocols.

Results and Observation

A total of 2384 children were admitted over a period of 7 years from July, 2014 to June, 2021.Out of these,1004 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were chosen for further evaluation.Amongst these,42 turned out to be malignant,with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of cases based on gender

| Gender | Total Number of Cases | Cases fulfilling inclusion criteria | Malignant Lesions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1349 | 622 | 19 |

| Female | 1035 | 382 | 23 |

Out of the 42 childhood malignancies assessed in our study,76.2% presented after 5 years of age.It was observed that malignancies in children were more common in the age group of 11–18 years,followed by 1–5 years,6–10 years and 0–1 years,with rates of 59.5%,21.4%,16.7% and 2.4% respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of childhood malignancy cases based on age

| Age | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0–1 years | 1 | 2.4% |

| 1–5 years | 9 | 21.4% |

| 6–10 years | 7 | 16.7% |

| 11–18 years | 25 | 59.5% |

A wide variety of tumour types were recorded,e.g.,Hodgkin’s lymphoma,non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,acute leukemia,papillary carcinoma thyroid,nasopharyngeal carcinoma,Langerhans cell histiocytosis,rhabdomyosarcoma,olfactory neuroblastoma and salivary gland neoplasm (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Most common Head and Neck Malignancies as per age group(in our study)

| Age Group | Type of Head and Neck Malignancy most prevalent |

|---|---|

| 0–1 years | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| 1–5 years |

Rhabdomyosarcoma Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Hodgkin’s lymphoma Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis Leukemia |

| 6–10 years |

Hodgkin’s lymphoma Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Rhabdomyosarcoma Papillary carcinoma thyroid Leukemia |

| 11–18 years |

Papillary carcinoma thyroid Olfactory neuroblastoma Hodgkin’s lymphoma Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Nasopharyngeal carcinoma Salivary gland neoplasms |

Table 4.

Anatomical locations of childhood malignancies in otorhinolaryngology(in our study)

| Site | Subtotal | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | 22 | 52.3% | |

|

• Hodgkin’s lymphoma • Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma • Acute Leukemia • Nasopharyngeal carcinoma • Papillary carcinoma thyroid |

4 4 8 2 4 |

||

| Nasopharynx | 8 | 19.0% | |

|

• Hodgkin’s lymphoma • Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma |

3 5 |

||

| Nose and paranasal sinuses | 4 | 9.6% | |

|

• Olfactory neuroblastoma • Rhabdomyosarcoma |

3 1 |

||

| Ear/Temporal Bone | 4 | 9.6% | |

|

• Langerhans’s cell histiocytosis • Rhabdomyosarcoma |

3 1 |

||

| Parotid | 2 | 4.7% | |

|

• Mucoepidermoid carcinoma • Round cell tumour |

1 1 |

||

| Oropharynx | 1 | 2.4% | |

| • Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 | ||

| Facial Region | 1 | 2.4% | |

| • Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 |

Discussion

Malignancies are uncommon in children.While 1 out of 3 adults will develop malignancy during his/her lifetime,only 1 in 285 children will develop malignancy before the age of 20 years.Childhood malignancies display diverse patterns of biological behaviour.Incidence of head and neck tumours in children is relatively rare,accounting for less than 1% of all cancer cases in the United States.An estimated 11,050 children younger than 15 and 5,800 teens ages 15–19 in the United States are newly diagnosed with cancer each year [5] 0.5% of all childhood cancers are head and neck malignancies,thereby affecting approximately 842 children every year [5]. Other studies also confirm this ever-increasing trend.Currently,more than 80% of children diagnosed with cancer will become long-term survivors in high income countries(HICs) [6]. Low and middle-income countries(LMICs),including India,account for nearly 90% of paediatric population and more than 80% of childhood cancer burden [7, 8]. Childhood cancer in India accounts for 0.7–4.4% of total cancer diagnoses as per PBCR report(2012-14) which is similar to previous PBCR report of 0.5–5.8%(2009-11) [9, 10]. Five-year survival rates vary by types of cancer.The 5-year survival rate for children under 15 years of age has improved from 58% to 1970s to 84% in 2020,thanks to major treatment advances and participation in clinical trials.For teens aged 15–19 years,the 5-year survival rate for all cancers is 85%.

In otorhinolaryngology practice,many patients present with symptoms related to childhood malignancy.In the present study,lymphoma,acute leukemia,nasopharyngeal carcinoma,thyroid carcinoma,Langerhans cell histiocytosis,rhabdomyosarcoma,olfactory neuroblastoma and salivary gland malignancies are recorded in order of frequency and discussed below.

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

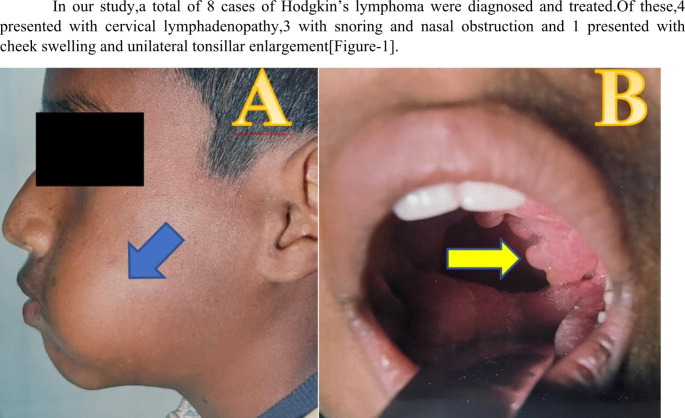

Hodgkin’s lymphoma comprises 6% of childhood cancers.In the United States,its incidence is age-related and is highest among adolescents aged 15–19 years(29 cases/1 million/year);children aged 10–14 years, 5–9 years and 0–4 years have approximately threefold,eightfold and 30-fold lower rates respectively than adolescents [11]. In developing countries,there is a similar incidence rate in young adults but higher incidence rate in childhood [12]. The male:female ratio varies markedly with children younger than 5 years showing a male predominance(M:F = 5.3) and children aged 15–19 years showing female predominance(M:F = 0.8) [13]. There is an association between Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Epstein-Barr virus(EBV) infection,with many children having evidence of prior exposure and in-situ hybridization demonstrating Epstein–Barr genomes in the pathognomonic Reed–Sternberg cell [14]. Hodgkin’s lymphoma is histologically separated into two broad categories:‘classical’ Hodgkin’s lymphoma(90%),comprising lymphocyte-depleted(rare in children),nodular sclerosing and mixed cellularity subtypes,and ‘lymphocyte-predominant’ Hodgkin’s lymphoma (10%). The presenting features of Hodgkin’s lymphoma result from direct or indirect effects of nodal or extranodal involvement and/or constitutional symptoms related to cytokine-release from Reed-Sternberg cells and cell-signalling within the tumour microenvironment [15]. Hodgkin’s lymphoma commonly presents in children with tonsillar asymmetry as the most common sign,asymptomatic cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy,with/without systemic constitutional symptoms(fever,weight loss and night sweats),which unfavourably affect prognosis.The lymphadenopathy is described as firm,rubbery and non-tender.Snoring is commonly noted in patients under 5 years of age,clinical lymphadenopathy is frequent among patients aged 6–10 years and dysphagia is a common sign in patients between 11 and 18 years.Lymph node biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.Treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma is based on stratification of risk groups determined by histology,stage at presentation,number of involved sites,disease bulk and presence/absence of constitutional symptoms. Treatment plan for Hodgkin’s lymphoma includes chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.Surgery is not commonly used as a treatment but may sometimes be used for localized nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma,where the involved lymph nodes can be completely removed by surgery.The 5-year survival rate for children and adolescents with Hodgkin’s lymphoma is 98% and 97% respectively [16] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A)Clinical image of a patient of Hodgkin’s lymphoma with left cheek swelling(blue arrow) and B)Intra-oral image of the same patient with left tonsillar enlargement(yellow arrow)

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma(NHL)

NHL is rare in children under 3 years and is commoner in boys.Each year in the United States,an estimated 1,050 children and teens under the age of 20 are diagnosed with NHL,accounting for 7% of all cancers in that age group.Risk for the disease increases with age and has a male preponderance [17]. Histologically,NHL is divided into low,intermediate and high grade.Children commonly present with high-grade variety of NHL [18]. About 90% of childhood NHLs are mature B-cell lymphomas [Burkitt(40%) or diffuse large B-cell(10%)], lymphoblastic lymphomas(30%) or anaplastic large cell lymphomas(10%)]. The remaining 10% consist of diseases commonly seen in adults-follicular lymphoma,mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and mature T-cell lymphoma [19]. Immunodeficient individuals have an increased risk of NHL,predominantly of the mature B-cell type and these are associated with EBV.Childhood NHL accounts for 5–10% of cases in head and neck region,with asymptomatic cervical lymphadenopathy being the most common presentation.Other regions that may be involved includes salivary glands,larynx,sinuses and orbit.NHL also manifest in the extranodal lymphoid tissue of Waldeyer’s ring,presenting as an asymmetric tonsillar enlargement or mimicking adenoidal hypertrophy.Tonsillar asymmetry alone,without consideration of other factors such as constitutional symptoms(fever,weight loss and night sweats),history of rapid unilateral enlargement or associated cervical lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly,does not imply malignancy as up to 1/5th of children undergoing routine tonsillectomy may have some degree of coincidental innocent tonsillar asymmetry [20]. Excisional biopsy of lymph nodes is the gold standard for diagnostic evaluation.Diagnosis can also be made by using less invasive techniques like image-guided cutting needle biopsies and cytopathological and immunohistochemical techniques with small specimens [21]. Treatment for paediatric NHL is based on aggressive multiagent chemotherapy depending on the histology and disease stage. The commonly used agents include CHOP-based regimens(cyclophosphamide,hydroxydaunomycin,vincristine and prednisone).Radiotherapy is not routinely used for local NHL treatment but is used in central nervous system(CNS) prophylaxis [22]. The disease-free survival period for paediatric NHL is rising with the continuously evolving treatment regimes,resulting in long-term survival being achieved in over 80% [19]. In general,5-year survival rate for children with NHL is about 91% and depends on the specific subtype of NHL and the stage of disease.

In our study,we encountered 4 cases of childhood NHL all of whom presented with cervical lymphadenopathy.

Leukemia

In otorhinolaryngologic practice,leukemic lesions are frequently misdiagnosed or their possible significance is entirely overlooked.In acute leukemia,the occurrence of necrotic lesion on the inside of cheek,enlarged/ulcerated/membranous tonsil,bleeding gums,acute stomatitis,epistaxis or rapidly developing cervical lymphadenopathy is often the first symptom of the disease.In chronic leukemia,the patient overlooks/neglects an enlarged spleen/liver,dyspnoea,generalised weakness,unexplained loss of weight and appetite or moderate fever,but seeks medical care only in cases of epistaxis,prolonged haemorrhage after extraction of a tooth,bleeding of the gums,disturbing lesion of the mouth or oral cavity/oropharynx,sudden deafness and vertigo.Ordway and Gorham [23], in their monograph “Diseases of the Blood”,stated:“The four outstanding landmarks causing one to suspect that an unknown condition in any particular person may be a disease of the blood are-(1)anemia,(2)enlargement of the lymph glands or spleen,(3)hemorrhage into the tissues or from the mucous surfaces and (4) throat lesions,particularly of the membranous or ulcerative type,varying greatly in degree,extent and type.“The anemia is evident by pale colour of the conjunctivae,gums and other intra-oral and pharyngeal structures.Enlargement of lymph glands of the neck is present in most cases of leukemia.Hemorrhage from the mucous membrane surfaces of mouth and pharynx or the middle and inner ear,or both,or from the nose is a frequent finding.Ulcerative lesions of the mouth,throat and larynx occur in a large number of cases and are evident on clinical examination.Thus,one can see that the four outstanding manifestations causing one to suspect the existence of a blood dyscrasia may evident themselves in the fields of otorhinolaryngology.The finding of one or more of these lesions in a given case indicates the need of a detailed hematologic study.

In our study,we recorded 8 cases of leukemia,all of whom presented with cervical lymphadenopathy and unexplained pallor.Out of the 8,three patients had history of gum bleeds,2 had membrane over the faucial tonsils and 1 had unresolved oral ulcers.After diagnosing the cases,they were referred to the Department of Hematology for further management.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma(NPC)

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma refers to tumours arising from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx.Median age of development of NPC in children is 13 years and incidence is higher in males [24]. The cause of NPC is attributed to many factors–EBV infection,genetic predisposition and environmental factors like high intake of preserved food and smoking.The WHO classification of NPC includes type I(keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma), type II(nonkeratinizing carcinoma) and type III(undifferentiated carcinoma).In children,undifferentiated carcinoma(type III) is the most common histopathological type [24]. NPC may present in three ways– (1) a painless upper neck mass, (2) the mass may enlarge and block the nose, giving a stuffy nose and nasal intonation to speech,or block the eustachian tube resulting in serous otitis media with hearing loss and (3) it may erode the base of skull,resulting in cranial nerve palsies(commonly trigeminal,abducens and facial nerve palsy).Elevated IgA viral capsular antigen(VCA) and early intracellular antigen(EA) is used for screening in high-risk regions.Investigation include diagnostic biopsy with histopathological analysis,CT and/or MRI of the primary site and may include chest CT, abdominal ultrasound/CT and bone marrow biopsy for metastasis screening.Treatment of NPC follows guidelines established for adults with high-dose radiotherapy to the nasopharynx and involved neck lymph nodes. However,childhood NPC is distinguished from adult NPC by its close association with EBV,predominance of type III histology and high incidence of advanced-stage disease [25]. In a study conducted by Orbach et al.,5-year survival rates in patients receiving first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin,5-flurouracil) with/without radiotherapy was 73% [26]. In children,extensive surgical resection like the maxillary swing procedure are not performed due to skeletal immaturity,chances of recurrence due to incomplete resection and risk of surgical morbidity.

In our study,we diagnosed 7 cases of NPC.Of these,5 presented with symptoms of nasal obstruction,epistaxis and snoring,and 2 presented with a painless level 2 cervical node.

Papillary Carcinoma Thyroid(PCT)

Paediatric thyroid cancer is rare.Risk factors include family history and previous radiation exposure.Sporadic papillary thyroid cancer represented 1.4% of newly diagnosed childhood carcinomas in the USA(1975–1995) according to the SEER database [27]. Interestingly,incidence among gender lines changes according to age group with males having 6:1 increased incidence at ages 5–9,a similar incidence among males and females from ages 10–14 and a ratio more consistent with adult patients with 5:2 female:male ratio after 14 years of age [27]. Thyroid cancer is suspected when a solitary thyroid nodule is identified in children and adolescents,with 20% estimated to represent malignancy compared with 5% in adults [28]. Initial investigation includes measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone(TSH),calcitonin(for diagnosis of MTC) and neck ultrasound scan. Ultrasound features suggestive of malignancy include indistinct margins,microcalcifications and variable echogenicity.In adults,fine needle aspiration(FNA) may be useful for distinguishing benign and malignant nodules but data are limited in children.When the aspirate demonstrates malignancy,surgery is recommended.When the cytology is indeterminate or inadequate,options include repeating ultrasound-guided FNA within 3–6 months or proceeding to surgery,after discussion of risk-to-benefit ratio.In young children at higher risk of malignancy(under 10 years of age,previous radiation exposure,family history of thyroid cancer),prompt surgical treatment is advisable and FNA is not required.The surgical approach for children remains controversial due to the balance between improved disease eradication and possibly increased risk from total thyroidectomy versus increased chance of residual or recurrent disease with hemithyroidectomy.Hence, hemithyroidectomy is a reasonable approach with total thyroidectomy(initial/completion) in the presence of definitive cancer diagnosis [29]. Central compartment lymph node dissection for palpable or ultrasound-detected nodes is recommended at the time of total/completion thyroidectomy.

In our study, we recorded 4 cases of PCT, all of whom presented with anterior neck swelling.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LHC)

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is an uncommon disorder characterized by an abnormal accumulation of histiocytes.LHC does not have age predilection.Peak incidence is between 1 and 4 years of age.The incidence of LCH in children is determined as 2–9/1,000,000/year,with a male-to-female ratio of 1.2–1.4:1 [30]. LCH may mimic common paediatric head and neck disorders like otitis media,skin rash or cervical lymphadenopathy.50% of LCH patients may present with only a solitary head and neck finding [31]. Common presentations of the disease include ear pain,swelling behind the ear,aural discharge,hearing loss,vertigo and facial nerve paralysis,which is similar to our experience [31]. Once clinical suspicion is aroused,diagnosis is based on clinical history, histology and imaging.Tissue sample is required for definitive diagnosis.CT and MRI are useful in delineating extent of the disease.Treatment includes observation,single/multi-agent chemotherapy and radiation,depending on the presentation.Localised skin lesions in younger patients regress spontaneously. If it persists,topical corticosteroids with low-dose chemotherapy can be given.Radiation therapy is no longer used for head and neck LCH due to its potentially severe morbidities,its lack of acceptable primary or adjuvant control and high risk of secondary malignancies [32]. Although LCH is very critical, the prognosis is generally good if vital organs are spared,timely diagnosis made and prompt rational treatment given.The prognosis of temporal bone LCH is excellent in patients with limited organ involvement [33]. Besides the extent of the disease,age of patient at the time of diagnosis is an important factor. Indicators of poor prognosis include children < 2 years of age,presence of cervical lymph nodes,scalp involvement,multisystem involvement and vital organ dysfunction.

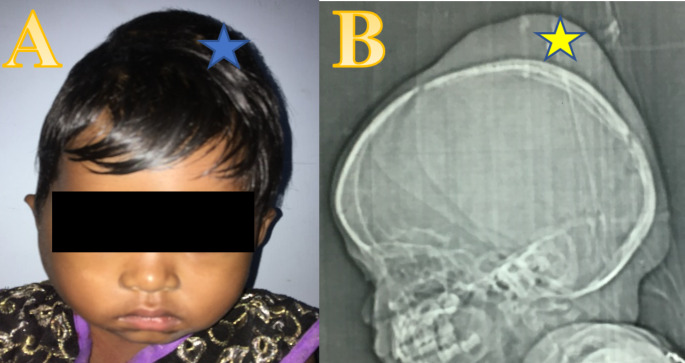

In our study, we recorded 3 cases with LHC, all of whom presented with ear discharge not responding to treatment, hearing loss and lytic lesions over the skull and temporal bone (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A)Clinical image and B)Radiological image of a patient of Langerhans cell histiocytiosis with skull lesion(blue and yellow star)

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the commonest soft-tissue malignancy in children,40% of which occur in the head and neck region.There are two peaks in incidence–one at 2–6 years and another at 10–18 years [34]. In head and neck region,the common sites are orbit,nasopharynx,middle ear/mastoid and sinonasal cavity.It is the most common temporal bone malignancy of childhood and arises from either the tensor tympani or stapedius.Regional lymph node involvement is seen in 20% of cases.These tumours are of mesenchymal origin and is within the category of small blue cell tumours,which includes neuroblastoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumours.The embryonal form is common at birth and incidence declines with age and the alveolar form peaks in childhood and adolescence [35]. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma comes in spindle-cell and botryoid variants and has better prognosis [36]. Many alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas carry chromosomal translocations,with the PAX3-FKHR gene translocation suggesting the poorest prognosis,particularly with metastasis [37]. Rhabdomyosarcomas typically present as an asymptomatic mass and an open/core needle biopsy is required to provide adequate tissue for histopathologic and molecular analysis.Head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma usually manifests as a localized painless mass with high frequency of lymphatic and distant metastasis [38]. Rhabdomyosarcoma is rarely cured by one modality alone.So multimodal treatment is indicated.This consists of chemotherapy and surgery/radiotherapy,based on tumour site and stage.Surgery is usually the first treatment for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma without distant metastasis [39]. If the tumour cannot be completely removed or is inoperable/unresectable,it is treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy to destroy the cancer cells.The IRS-IV study protocol resulted in 5-year survival rates of 97% in embryonal nonorbital,non-parameningeal head and neck cases and 67% in the alveolar cases [40].

We diagnosed 3 cases of rhabdomyosarcoma,of which 1 presented with aural fulness and hearing impairment,1 with facial palsy and 1 with nasal obstruction.

Olfactory Neuroblastoma (ONB)

Olfactory neuroblastoma also called esthesioneuroblastoma is rare in children [41]. The incidence of ONB among the malignancies of nasal cavity in children was reported to be 25% [42]. The World Health Organization(WHO) classification groups this entity under the neuroectodermal tumors with Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor family [43]. Most children present with symptoms caused by nasopharyngeal mass or extension of tumor into the intracranial structures. These include nasal obstruction,epistaxis,rhinorrhea, headache,decrease in visual acuity,diplopia/proptosis or anosmia. Investigations include nasal endoscopy and biopsy, including immunohistochemical analysis, CT scans and MRI. Kadish classification is used for staging [44]. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy/radiotherapy) is also required in some. Kadish staging system,lymph node status, treatment modality and age were reported to have significant prognostic impact on survival. Locoregional recurrence is the commonest cause of treatment failure and high rates of late recurrence warrant long-term follow-up of the patients with ONB, with clinical and radiological examinations.

A male preponderance was noted among the patients reported in the literature [41], but in our study that included 3 patients,2 were female and 1 was male.All the 3 patients presented with rhinorrhoea,nasal obstruction and snoring.One patient had intracranial extension and presented with added symptoms of seizures and diplopia.

Childhood Salivary Gland Tumours

Salivary gland cancer is one of the five main types of cancer in head and neck region,a grouping called “head and neck cancer”,the others being laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers,nasal cavity and paranasal sinus cancers,oral and oropharyngeal cancers and nasopharyngeal cancers.Salivary gland neoplasms are rare in childhood,but after exclusion of vascular lesions,approximately half are malignant.Malignant lesions are common in older children,with good prognosis.Five-year survival is similar to adults.Cancer confined to the salivary gland has 94% 5-year survival rate.Cancer with spread outside the salivary gland has 65% 5-year survival rate.Cancer with spread to distant parts of the body has 35% 5-year survival rate.Majority of salivary malignancies occur in the parotid gland,in which the most common lesion is mucoepidermoid carcinoma and in contrast to adults,most submandibular gland and minor salivary gland tumours are benign [45]. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is also the commonest radiation-induced salivary gland tumour in children [46]. Other malignant lesions described include acinic cell carcinoma,adenoid cystic carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Diagnosis of salivary gland tumours is made based on clinical examination,fine needle aspiration cytology,contrast-enhanced CT scans and MRI,if/when necessary.Treatment of newly diagnosed salivary gland cancer in children includes surgery to remove the cancer and/or internal or external radiation therapy after surgery,whenever necessary.While there is no standard protocol for treating desmoplastic round cell tumours,treatment includes neoadjuvant HDP6 regimen-high-dose cyclophosphamide,doxorubicin and vincristine(HD-CAV),alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide(IE) chemotherapy,which our patient received in the Cancer Centre of our hospital.Surveillance is dependent on tumor resection margins,tumor subtype and ease of clinical assessment by palpation.A baseline MRI scan may be indicated once surgical healing is complete,with follow-up MRI scanning as in adults.

In our study,we recorded two cases of salivary gland tumours–one was a mucoepidermoid tumour involving the right parotid gland and the other was a desmoplastic round cell tumour involving the left parotid gland (Fig. 3). Both the patients presented with a painless lump on the face and inability to move some facial muscles (progressive facial muscle paralysis).

Fig. 3.

Clinical image of a patient with a left parotid swelling

Conclusion

Incidence of head and neck tumors in pediatric age group is rare.It is 1.76% of pediatric patients attending the ENT department in 7 calendar years.Amongst the malignant lesions,lymphomas are most frequent.Incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is more than non-Hodgkin’s disease.Commonest age of presentation of the malignant diseases is above 10 years.There is an overall female predominance with a male:female ratio of 1:1.2.The incidence patterns of childhood cancers are similar in different countries,suggesting that lower proportion of these cancers are related to exogenous exposure.Pediatric malignancy is a treatable disease,but early diagnosis is very important.Awareness of a potential malignancy and careful follow-up of children with suspicious head and neck cancers is mandatory for early diagnosis and prompt treatment.All the three modalities of treatment-surgery,chemotherapy and radiotherapy are required to treat most of the childhood cancers,along with good supportive care.

Financial Disclosure

No grant or financial aid availed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest during the making of this manuscript.

Consent

Written and informed consent was obtained from the patients/patient’s guardians regarding the use of the patient’s pictures, clinical findings and reports of the investigations that were conducted.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LAG, et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001-10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):719–731. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30186-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SL (2000) Deaths: final data for 1998. Natl Vital Stat Rep. Jul 24;48(11):1-105. PMID: 10934859 [PubMed]

- 3.Albright JT, Topham AK, Reilly JS. Pediatric head and neck malignancies: US incidence and trends over 2 decades. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:655–659. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson PV, Davidoff AM. Malignant neoplasms of the head and neck. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:92–98. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Internet]. Cancergoldstandard.org. 2020 [cited 27 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.cancergoldstandard.org/sites/default/files/research/2020_Cancer%20Facts%20%26%20Figures%202020.pdf

- 6.Gupta S, Howard SC, Hunger SP et al Treating Childhood Cancer in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. In: Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, editors. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3). Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2015 Nov 1. Chapter 7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343626/ doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0349-9_ch7

- 7.Magrath I, Steliarova-Foucher E, Epelman S, Ribeiro R, Harif M, Li C, et al. Paediatric cancer in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):e104–e116. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faruqui N, Bernays S, Martiniuk A, Abimbola S, Arora R, Lowe J et al (2020) Access to care for childhood cancers in India: perspectives of health care providers and the implications for universal health coverage.BMC Public Health. ; 20(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bashar MA, Thakur JS. Incidence and pattern of Childhood Cancers in India: findings from Population-based Cancer Registries. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(2):240–241. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_163_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Three Year Report of PBCR 2012–2014 [Internet]. Ncdirindia.org. 2020 [cited 27 December 2020]. Available from: https://ncdirindia.org/ncrp/ALL_NCRP_REPORTS/PBCR_REPORT_2012_2014/index.htm

- 11.PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. Childhood Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version (2020) Dec 18. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65726/

- 12.Zhou L, Deng Y, Li N et al (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of Hodgkin lymphoma from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease study. J Hematol Oncol. ;12(1):107. Published 2019 Oct 22. doi:10.1186/s13045-019-0799-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Allen C, Kelly K, Bollard C. Pediatric Lymphomas and Histiocytic Disorders of Childhood. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(1):139–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cickusić E, Mustedanagić-Mujanović J, Iljazović E, Karasalihović Z, Skaljić I (2007 Feb) Association of Hodgkin’s lymphoma with Epstein Barr virus infection. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 7(1):58–65. 10.17305/bjbms.2007.3092PMID: 17489771; PMCID: PMC5802289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wang HW, Balakrishna JP, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. Diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma in the modern era. Br J Haematol. 2019;184(1):45–59. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lymphoma - Hodgkin - Childhood - Statistics [Internet]. Cancer.Net. 2020 [cited 27 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/lymphoma-hodgkin-childhood/statistics#:~:text=The%205%2Dyear%20survival%20rate%20for%20children%20with%20Hodgkin%20lymphoma,Hodgkin%20lymphoma%20are%20an%20estimate

- 17.O’Leary M, Sheaffer B, Keller F, et al. et al. Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial neoplasms. In: Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG, et al.et al., editors. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975–2000. Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute; 2006. pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandlund JT, Downing JR, Crist WM. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1238–1248. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross TG, Termuhlen AM. Pediatric non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:459–465. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harley EH. Asymmetric tonsil size in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:767–769. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.7.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Kerviler E, de Bazelaire C, Mounier N, et al. Image-guided core-needle biopsy of peripheral lymph nodes allows the diagnosis of lymphomas. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:843–849. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkhardt B, Woessmann W, Zimmermann M, et al. Impact of cranial radiotherapy on central nervous system prophylaxis in children and adolescents with central nervous system-negative stage III or IV lymphoblastic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:491–499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ordway T, Gorham LW. Diseases of the blood: Oxford Monographs on diagnosis and treatment. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayan I, Altun M. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children: retrospective review of 50 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:485–492. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)80010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayan I, Kaytan E, Ayan N. Childhood nasopharyngeal carcinoma: from biology to treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:13–21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)00956-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orbach D, Brisse H, Helfre S, et al. Radiation and chemotherapy combination for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in children: radiotherapy dose adaptation after chemotherapy response to minimize late effects. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:849–853. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gayathri BN, Sagayaraj A, Prabhakara S, Suresh TN, Shuaib M, Mohiyuddin SM. Papillary thyroid carcinoma in a 5-year-old child-case report. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2014;5(4):321–324. doi: 10.1007/s13193-013-0282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keh SM, El-Shunnar SK, Palmer T, Ahsan SF (2015 Jul) Incidence of malignancy in solitary thyroid nodules. J Laryngol Otol 129(7):677–681 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Addasi N, Fingeret A, Goldner W. Hemithyroidectomy for thyroid Cancer: a review. Medicina. 2020;56(11):586. doi: 10.3390/medicina56110586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinn DJ, Chakraborty R, Allen CE (2016 Feb) Langerhans Cell histiocytosis: emerging insights and clinical implications. Oncology (Williston Park). 30:122–32, 139. PMID: 26888790. 2 [PubMed]

- 31.Ni M, Yang X. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13(3):1051–1053. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchmann L, Emami A, Wei JL. Primary head and neck Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2006;135(2):312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng H, Xia Z, Cao W et al (2018) Pediatric Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone: clinical and imaging studies of 27 cases. World J Surg Oncol 16(1). 10.1186/s12957-018-1366-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Miller RW, Young JL, Jr, Novakovic B. Childhood cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:395–405. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<395::AID-CNCR2820751321>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, et al. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1978–2001: an analysis of 26 758 cases. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2922–2930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leaphart C, Rodeberg D. Pediatric surgical oncology: management of rhabdomyosarcoma. Surg Oncol. 2007;16:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oda Y, Tsuneyoshi M (2008) ; 100:200– 208. This study provides a useful summary of recent advances in the molecular pathology of soft tissue sarcomas, including prognostic markers and potential targets for molecular therapy

- 38.Lin JW, Wu GH, Zeng ZY, Chen WK, Guo ZM, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical features and diagnosis of head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma: a report of 24 cases. Ai Zheng. 2008;27:618–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daya H, Chan HS, Sirkin W, et al. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck: is there a place for surgical management? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:468–472. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pappo AS, Meza JL, Donaldson SS, et al. Treatment of localized nonorbital, nonparameningeal head and neck rhabdomyosarcoma: lessons learned from intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma studies III and IV. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:638–645. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bisogno G, Soloni P, Conte M et al (2012) Esthesioneuroblastoma in pediatric and adolescent age. A report from the TREP project in cooperation with the Italian Neuroblastoma and Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committees. BMC Cancer. ;12:117. Published 2012 Mar 25. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Wormald R, Lennon P, O’Dwyer TP (2011 Apr) Ectopic olfactory neuroblastoma: report of four cases and a review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268(4):555–560. 10.1007/s00405-010-1423-8Epub 2010 Nov 16. PMID: 21079984 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Hafezi S, Seethala RR, Stelow EB, et al. Ewing’s family of tumors of the sinonasal tract and maxillary bone. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5(1):8–16. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lao WP, Thompson JM, Evans L, Kim Y, Denham L, Lee SC. Mixed olfactory neuroblastoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma: an unusual case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2020;11:97. doi: 10.25259/SNI_473_2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.To VS, Chan JY, Tsang RK, Wei WI. Review of salivary gland neoplasms. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:872982. doi: 10.5402/2012/872982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ritwik P, Cordell KG, Brannon RB (2012) Minor salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma in children and adolescents: a case series and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. ;6:182. Published 2012 Jul 3. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]