Abstract

This study investigated to what extent socioeconomic status (SES) disparity associates with cognitive and physical impairment within older Asian Americans in comparison with other races/ethnicities. Data were from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2018 that included 3,297 White, 1,755 Black, 1,708 Hispanic, and 730 Asian Americans aged ≥ 60. Physical functioning was measured by activities of daily living (ADL) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Memory and language fluency were evaluated using the Alzheimer's Disease Word List Memory Task and Animal Fluency Tests, respectively. Multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to investigate the association between SES and physical and cognitive impairment within racial/ethnic groups, and seemingly unrelated regressions compared coefficients across subgroups. Asians with ≤ high school education had the highest prevalence of age- and sex-adjusted memory impairment among all races/ethnicities, while no difference was observed for those with > high school education. ADL/IADL disability odds did not differ between Asians and Whites, but Asians were more likely to exhibit impaired verbal fluency. Education disparity for ADL disability (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 2.20–5.25) and memory impairment (OR, 11.57; 95% CI, 6.59–20.31) were largest among Asians compared to Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Income disparity for function impairment showed no significant difference across racial/ethnic groups (all P > 0.05). Asians experienced the highest burden of physical functioning and memory impairment due to education disparity. Efforts should focus on strengthening research infrastructure and creating targeted programs and services to improve cognitive and physical health for racially/ethnically underrepresented older adults with lower education attainment.

Keywords: Social Determinants of Health, Racial Discrimination, Dementia, Physical Health, Elderly

Introduction

Cognitive and physical functioning impairments are highly prevalent among older adults. An estimated one-third of Americans aged 65 and older have some level of cognitive impairment, and 40% have at least one type of physical disability [1, 2]. However, the degree of functional impairment varies among older adults as they age. A wealth of literature has demonstrated the impact of socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities on older adults’ health status [3]. For instance, Black and Latino older adults tend to have a higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s and related dementias than their White counterparts [4, 5]. Compared to Whites and Blacks, Hispanic older adults are reported to have the highest prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Lower educational attainment has also been associated with higher risks of both dementia and MCI [2]. In addition, racial/ethnic minorities, including Blacks, Hispanics, Native Indians/Alaskan Natives, and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, all reported higher activity of daily living disabilities and poorer mental health status compared to Whites [6].

Prior research on Asian American health outcomes tends to show Asians have better health status, including lower risk of dementia and better overall physical functioning compared to other minority groups, and often perform as well as, or even better than, Whites in certain aspects [7, 8]. Consistent with these findings, Asian Americans are traditionally considered a “model minority”. The stereotype views Asians as a unique minority group with exceptional abilities to achieve high levels of financial and educational success within American society [9]. The model minority perspective treats Asian Americans as a monolithic group, failing to capture their many diverse backgrounds and experiences. The U.S. Census lists 21 different ethnic subgroups for those identifying as Asian alone, each with their unique culture, language, migration patterns, and socioeconomic status (SES) that greatly influence their health outcomes [10].

While Asian Americans have the highest median household income compared to other racial/ethnic groups, considering them as a homogenous group obscures significant within-group realities [11]. In fact, income inequality is rising fastest among this population, and the gap in standard of living between the highest and lowest earners has almost doubled in the last four decades [12]. While the poverty rate for Americans aged 65 and older was 8.9%, the rate for older Asian Americans was 9.3% [13]. Further, Asians in the top 10 percent of income make 10.7 times more than those in the bottom 10 percent [12]. The educational disparity among older Asian Americans broadly mirrors that of income disparity. According to recent estimates, 17% of Asian Americans have less than a high school education, significantly higher than the U.S. average at 11% [13]. These SES disparities are also closely associated with health disparities. For example, high-income Chinese older adults were observed to have decreased fall risk, lower pain rate, and greater likelihood of good sight and hearing evaluations compared to their low-income counterparts [14]. Asians with low SES may have significant structural barriers, including poor access to quality care, little familiarity with the American healthcare system, and lack of insurance. Approximately 85% of older Asians in the U.S. were born outside the country [15]. As a result of their immigration status, they may also face language barriers, cultural barriers, lack of social support, and discrimination that further impact their health status. Some studies have reported that Asians have higher rates of disability, increased self-reported symptoms of mental distress, and decreased likelihood of utilizing mental health care and specialist care compared to other racial/ethnic groups [16–18].

Disparities in SES across racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in the prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment within each racial/ethnic group [19]. Previous studies have reported the racial/ethnic and SES disparities associated with dementia, MCI, and physical functioning; however, to our knowledge, none of these studies report the SES disparities associated with the risk of functional impairment within the strata of races/ethnicities among older adults in the US. This study attempts to fill the gaps in the literature by investigating whether income and education disparities in the prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment exist within racial/ethnic groups (Asian, White, Black, and Hispanic) in a nationally representative sample of older adults in the US. Our study is significant in its consideration of within-group SES disparities that examines Asians through a more heterogenous perspective. As Asians have the largest income disparity in the US, we hypothesize that they will also have the largest health disparities of the four groups examined.

Methods

Data and Sample

This cross-sectional study analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2011 to 2018 [20]. This survey used a stratified, multistage probability sampling design to obtain information on the health, functional, and nutritional statuses of a national-representative U.S. population. NHANES data were collected first when participants were interviewed in their home, with a subsequent visit to a mobile examination center (MEC) where a clinical assessment including the cognitive performance test was carried out. Each sequential series of this survey oversampled low-income individuals, adults over the age of 60 years, and African and Hispanic Americans. Since 2011, NHANES has been oversampling Asian Americans in addition to traditionally oversampled groups [21]. Details of NHANES are available elsewhere [20]. The datasets are publicly available. The survey protocols were approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics.

Our study used the NHANES data from the 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, 2017–2018 cycles, as the publicly released data began including Asian Americans in 2011. Then, we excluded those who 1) aged < 60 (n = 26,276); 2) lacked data on education/income levels (n = 1,167); and 3) lacked data on cognitive and physical functioning measures (n = 2561). Included participants were younger, more likely to be Whites, more educated, higher income, more likely to be covered by health insurance, and more likely be current smoker than those excluded from these analyses (all P < 0.001). Our final analytical sample was 7,490 (aged 60 and older) participants.

Measurements

Race/Ethnicity

Race/ethnicity was self-reported by each participant. The racial/ethnic groups included non-Hispanic Whites (hereafter Whites), non-Hispanic Blacks (hereafter Blacks), Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Asians (hereafter Asians). We did not include other races/ethnicities or multi-races due to large heterogeneity within those groups.

Education and Income

Socioeconomic status was indicated by level of education and poverty-income ratio (PIR). Education was dichotomized to high school or less vs. more than high school. PIR is the ratio of household income from the last calendar year to the U.S. Census poverty thresholds for the year before the interview wave. Thus, a higher PIR indicates a higher socioeconomic status [22]. In this study, PIR is referred to as income.

Cognitive and Physical Functioning Impairment

Participants aged 60 years and older were eligible for cognitive performance tests that were done in the MEC in the requested language of the study participant, but were limited to English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese speakers. For those who spoke an Asian language, an interpreter was present during the interview. Detailed information on the cognitive performance tests, including quality assurance, quality control, data processing and editing, are described in the NHANES [23].

The cognitive performance tests included Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List Memory Task (CERAD-WL) for memory and Animal Fluency Tests (AFT) for language fluency. The CERAD-WL assesses the ability for new learning, consisting of three consecutive learning trials. For the learning trials, participants are instructed to read aloud 10 unrelated words, one at a time, as they are presented. Immediately after the presentation of the words, participants recall as many words as possible. In each of the three learning trials, the order of the 10 words is changed. The maximum score possible on each trial is 10. The score from the 3 trials is added to produce a total maximum CERAD-WL score of 30. The AFT assesses verbal fluency and is administered by asking participants to name as many animals as possible in 60 s, with a total score equal to the number of animals mentioned. Based on prior literature, cutoffs of < 17 for CERAD-WL and < 14 for AF were used to distinguish potential memory and language functioning impairment from healthy cognitive function and lack of cognitive impairment in the NHANES [24].

Physical functioning is measured by activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in NHANES [25]. Physical functioning impairment was measured by the inability to perform ADLs, which is defined as answering “some difficulty” or “much difficulty” in performing one or more of the following tasks: 1) getting in and out of bed, 2) eating, 3) dressing yourself, 4) walking between rooms on the same floor [25]. IADL disability is defined as answering “some difficulty” or “much difficulty” in performing one or more of the following tasks: 1) managing money, 2) performing house chores, 3) preparing meals [25].

Covariates

Following previous studies on examining the racial/ethnic differences in cognitive and physical health [4–8], our analyses were controlled for covariates, including age (60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and ≥ 80), sex (male vs. female), place of birth (foreign-born vs. US-born), language use (speaking more non-English than English at home, speaking both languages equally at home, speaking more English than non-English at home), marital status (married vs. divorced/widowed/separated/never married [i.e., not married]), health insurance (with vs. without), smoking status (current smoker, former smoker, or never smoked), and alcohol intake (≥ 12 drinks/year or < 12 drinks/year).

Statistical Analysis

We used NHANES 2-y MEC sampling weights to analyze the survey data and account for nonresponse, unequal probabilities of selection, and poststratification. The weighted percentages (%) were reported for all analytical variables, and the percentage differences between racial/ethnic groups were evaluated using chi-square tests. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence (with a 95% confidence interval) of cognitive and physical functioning impairment among Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians with different SES were reported.

SES disparities were assessed with multivariate logistic regressions with ADL/IADL disabilities and cognitive impairment (CERAD-WL or AFT) as dependent variables. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for place of birth, language use, marital status, health insurance, smoking, and alcohol intake, and the interaction terms between race/ethnicity and income or education were added in Model 3. We then performed seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) to compare the ORs between SES and each functional outcome within each racial/ethnic group [26]. To handle missing data, we used complete case analysis (i.e., pairwise deletion). Due to a low proportion of missing data (< 5%) for all variables, the overall bias using that approach is very low. Two-sided P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and Stata MP 17.0 (Statistical software, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics by race/ethnicity. A total of 3,297 Whites, 1,755 Blacks, 1,708 Hispanics, and 730 Asians were included in the analysis. Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians were younger and less likely to be insured (P < 0.001). Blacks were more likely to be current smokers and consume more alcohol (P < 0.001). A greater percentage of Whites (77.1%) and Asians (71.1%) were not in poverty compared with Blacks (64.4%) and Hispanics (54.1%, P < 0.001). Only 16.2% of Whites had a high school education or less, whereas more than half (53.9%) of Hispanics had a high school education or less (P < 0.001). More Blacks and Hispanics had ADL disability, IADL disability, and memory impairment compared to Whites (all P < 0.001). More Asians (45.0%) reported memory impairment measured by CERAD-WL (26.7% vs. 21.0%, P < 0.01) and impaired verbal fluency measured by AFT (45.0% vs. 18.3%, P < 0.001) as compared with Whites.

Table 1.

Demographics and prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment by race/ethnicity, NHANES 2011-2018a

| Whole (N = 7,490) | White (n = 3,297) | Black (n = 1,755) | Hispanic (n = 1,708) | Asian (n = 730) | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories, % | < .001 | |||||

| 60–64 | 29.4 | 19.0 | 37.0 | 39.2 | 34.7 | |

| 65–69 | 21.4 | 15.9 | 25.1 | 26.9 | 25.1 | |

| 70–74 | 17.4 | 19.7 | 13.7 | 16.5 | 17.7 | |

| 75–79 | 12.0 | 13.8 | 12.4 | 8.5 | 10.8 | |

| ≥ 80 | 19.8 | 31.6 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 11.8 | |

| Women, % | 50.7 | 50.4 | 48.8 | 52.5 | 53.0 | .086 |

| Not married, % | 43.9 | 42.3 | 58.5 | 39.7 | 26.1 | < .001 |

| Education attainment, % | < .001 | |||||

| ≤ High school | 28.8 | 16.2 | 27.9 | 53.9 | 29.2 | |

| > High school | 71.2 | 83.8 | 72.1 | 46.1 | 70.8 | |

| Income, % | < .001 | |||||

| PIR ≤ 1.3 (in poverty) | 31.4 | 22.9 | 35.6 | 45.9 | 28.9 | |

| PIR > 1.3 (not in poverty) | 68.6 | 77.1 | 64.4 | 54.1 | 71.1 | |

| No health insurance, % | 7.4 | 3.4 | 7.0 | 14.4 | 10.7 | < .001 |

| Smoking, % | ||||||

| Never | 50.5 | 46.3 | 45.7 | 54.8 | 70.1 | < .001 |

| Former | 36.7 | 42.9 | 33.6 | 33.4 | 23.9 | |

| Current | 12.8 | 10.7 | 20.7 | 11.8 | 6.0 | |

| Alcohol intake ≥ 12 drinks/year, % | 70.9 | 77.2 | 71.3 | 66.6 | 49.4 | < .001 |

| ADL disability, % | 20.8 | 18.9 | 27.7 | 31.2 | 20.4 | < .001 |

| IADL disability, % | 27.7 | 26.3 | 34.9 | 34.2 | 24.4 | < .001 |

| Memory impairment (CERAD-WL), % | 23.5 | 21.0 | 30.2 | 39.4 | 26.7 | < .001 |

| Verbal fluency impairment (AFT), % | 22.8 | 18.3 | 44.9 | 34.7 | 45.0 | < .001 |

PIR Poverty-Income Ratio, ADL Activities of Daily Living, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, CERAD-WL Consortium to Establish Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List, AFT Animal Fluency Test

aAll estimates were accounted for NHANES sampling weights

bChi-square tests were used to compare the racial/ethnic differences of each analytical variable

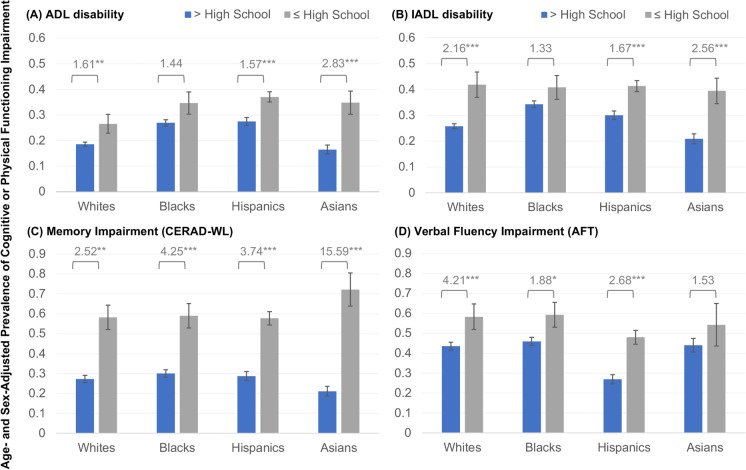

Figure 1 shows the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment by education levels. Within all races/ethnicities, the prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment was higher among older adults with lower levels of education (i.e., higher school or lower) (all P < 0.01). The prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment differed significantly by race/ethnicity with different education levels. For example, for older adults with higher education levels, the prevalence of ADL or IADL disabilities was lowest in Asians, whereas for those with lower education levels, no significant differences were identified among the four racial/ethnic groups (P > 0.05). Notably, Asians with lower education had the highest prevalence of memory impairment among all races/ethnicities, and no significant differences were observed for all racial/ethnic groups with higher levels of education.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment within racial/ethnic groups by education levels Note: ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; CERAD-WL = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List; AFT = Animal Fluency Test. Predicted prevalence were from weighted estimates, and all values were adjusted for age and sex. Numbers in the hat were odds ratios interpreted as the odds of participants being functionally impaired as compared with the reference group (based on multivariate logistic regression models). * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001

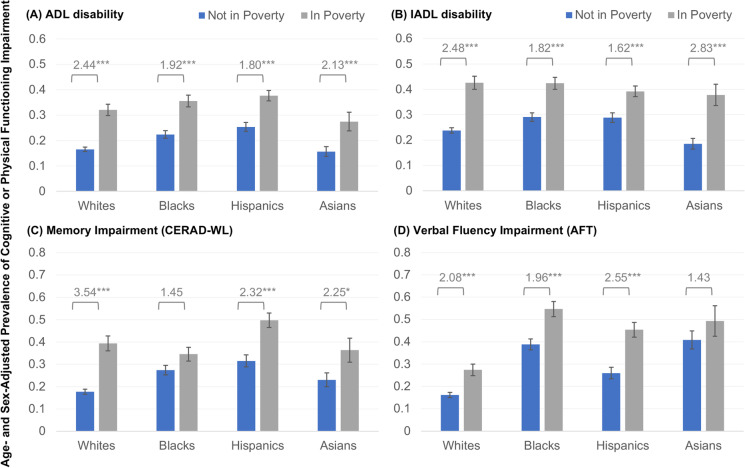

Figure 2 summarizes the prevalence by income level. The overall prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment was substantially higher among participants in poverty. Across the races/ethnicities, the overall prevalence of ADL or IADL disabilities was lowest among Asians not in poverty (all P < 0.05). However, the overall prevalence of ADL and IADL disabilities did not differ significantly among the four races/ethnicities living in poverty. In terms of cognitive impairment, Whites had the lowest prevalence among all races/ethnicities, and no significant differences were observed for Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians, net of poverty status.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of cognitive and physical functioning impairment within racial/ethnic groups by income levels. Note: ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; CERAD-WL = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List; AFT = Animal Fluency Test. Predicted prevalence were from weighted estimate,s and all values were adjusted for age and sex. Numbers in the hat were odds ratios interpreted as the odds of participants being functionally impaired as compared with the reference group (based on multivariate logistic regression models).* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001

In Table 2, the racial/ethnic differences in the odds of being cognitively or physically impaired were assessed, controlling for age and sex (Model 1). Blacks and Hispanics had higher odds of ADL disability, IADL disability, and memory impairment than Whites (all P < 0.001). The odds of having ADL/IADL disabilities did not differ with Asians and Whites; whereas Asians are more likely to have verbal fluency impairment than Whites (OR, 4.31; 95% CI, 3.05–6.08). Regression models additionally adjusted for other demographic and lifestyle factors in Model 2. The magnitude of regression coefficients was attenuated but still significant. Model 3 displays the interactions between race/ethnicity and income or education on cognitive or physical functioning impairment. The interaction between Asians and education was significant for ADL disability (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.38–5.48) and memory impairment (OR, 4.84; 95% CI, 1.25–18.69), suggesting that education disparities for cognitive and physical functioning impairment among Asians may be larger in magnitude than other races/ethnicities.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic status disparities and the odds of being cognitive and physical functioning impaired

| ADL disability | IADL disability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Intervals) | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Whites (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Blacks | 1.68 (1.43,1.98)*** | 1.54 (1.29,1.83)*** | 1.56 (1.30,1.87)*** | 1.56 (1.33,1.82)*** | 1.32 (1.11,1.56)** | 1.36 (1.14,1.62)*** |

| Hispanics | 1.80 (1.50,2.15)*** | 1.86 (1.54,2.25)*** | 1.82 (1.48,2.24)*** | 1.31 (1.09,1.57)** | 1.36 (1.12,1.65)** | 1.37 (1.11,1.68)** |

| Asians | 1.06 (0.84,1.34) | 1.12 (0.90,1.39) | 0.87 (0.65,1.16) | 0.86 (0.69,1.08) | 0.88 (0.70,1.11) | 0.86 (0.63,1.17) |

| Education attainment | ||||||

| > High school (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≤ High school | 1.68 (1.39,2.03)*** | 1.47 (1.20,1.80)*** | 1.20 (0.78,1.85) | 1.85 (1.50,2.27)*** | 1.55 (1.23,1.94)*** | 1.64 (1.04,2.60)* |

| Race/ethnicity × education | ||||||

| Whites × education (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Blacks × education | 1.03 (0.56,1.88) | 0.70 (0.37,1.30) | ||||

| Hispanics × education | 1.27 (0.77,2.09) | 0.93 (0.55,1.58) | ||||

| Asians × education | 2.75 (1.38,5.48)** | 1.22 (0.59,2.52) | ||||

| Income | ||||||

| Not in poverty (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| In poverty | 2.24 (1.89,2.66)*** | 2.06 (1.72,2.48)*** | 2.17 (1.68,2.80)*** | 2.25 (1.89,2.67)*** | 1.90 (1.58,2.29)*** | 2.02 (1.56,2.61)*** |

| Race/ethnicity × income | ||||||

| Whites × poverty (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Blacks × poverty | 0.88 (0.60,1.27) | 0.83 (0.57,1.20) | ||||

| Hispanics × poverty | 0.82 (0.57,1.18) | 0.75 (0.51,1.08) | ||||

| Asians × poverty | 0.97 (0.54,1.73) | 1.16 (0.66,2.05]) | ||||

| Memory impairment (CERAD-WL) | Verbal fluency impairment (AFT) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Intervals) | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Whites (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Blacks | 1.92 (1.50,2.46)*** | 1.63 (1.25,2.14)*** | 1.59 (1.20,2.11)** | 4.52 (3.53,5.78)*** | 4.16 (3.20,5.39)*** | 4.42 (3.38,5.78)*** |

| Hispanics | 2.34 (1.77,3.10)*** | 2.15 (1.61,2.87)*** | 2.04 (1.50,2.78)*** | 2.16 (1.62,2.88)*** | 2.14 (1.60,2.87)*** | 2.28 (1.66,3.13)*** |

| Asians | 1.49 (1.07,2.07)* | 1.34 (1.02,1.76)* | 1.08 (0.73,1.60) | 4.31 (3.05,6.08)*** | 3.59 (2.76,4.67)*** | 3.42 (2.04,5.73)*** |

| Education attainment | ||||||

| > High school (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≤ High school | 3.41 (2.49,4.66)*** | 3.19 (2.29,4.45)*** | 2.41 (1.32,4.38)** | 3.02 (2.20,4.14)*** | 2.80 (2.02,3.88)*** | 3.87 (2.21,6.77)*** |

| Race/ethnicity × education | ||||||

| Whites × education (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Blacks × education | 1.53 (0.64,3.64) | 0.41 (0.18,0.94)* | ||||

| Hispanics × education | 1.46 (0.72,3.00) | 0.65 (0.33,1.28) | ||||

| Asians × education | 4.84 (1.25,18.69)* | 0.39 (0.12,1.30) | ||||

| Income | ||||||

| Not in poverty (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| In poverty | 2.87 (2.21,3.73)*** | 2.70 (2.02,3.60)*** | 3.33 (2.27,4.89)*** | 2.07 (1.65,2.60)*** | 1.91 (1.50,2.44)*** | 1.85 (1.31,2.62)*** |

| Race/ethnicity × income | ||||||

| Whites × poverty (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Blacks × poverty | 0.43 (0.25,0.73)** | 1.01 (0.61,1.68) | ||||

| Hispanics × poverty | 0.63 (0.37,1.08) | 1.36 (0.80,2.31) | ||||

| Asians × poverty | 0.54 (0.25,1.17) | 0.81 (0.37,1.78) | ||||

ADL Activities of Daily Living, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, CERAD-WL Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List, AFT Animal Fluency Test

All models were adjusted for NHANES sampling weights to account for nonresponse, unequal probabilities of selection, and poststratification

Model 1 were adjusted for age and sex

Model 2 were further adjusted for place of birth, language use, marital status, health insurance, smoking, and alcohol intake

Model 3 were added the interaction terms between race/ethnicity and education or income

* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001

In Table 3, the ORs of cognitive or physical functioning impairment are displayed within racial/ethnic groups after adjusting for all covariates. SES disparities for ADL disability (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 2.20-5.25) and memory impairment (OR, 11.57; 95% CI, 6.59-20.31) were largest among Asians compared to Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Asians with ≤high school education had 3.40 the odds of being ADL impaired and 11.57 the odds of being memory functioning impaired than Asians with >high school education. Results from seemingly unrelated regressions confirmed that education disparity for ADL disability and memory impairment are larger in magnitude among Asians compared to other races/ethnicities (P < .05). Education differences in cognitive or physical functioning impairment were not observed in Blacks (all P < .001), but Hispanics with ≤ high school education had higher odds of being cognitively or physically impaired than Hispanics with >high school education (all P < .001).

Table 3.

Relative odds of cognitive and physical functioning impairment in Asian older adults relative to White, Black, and Hispanic older adults with different socioeconomic status

| ADL disability | IADL disability | Memory impairment (CERAD-WL) | Verbal fluency impairment (AFT) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95 % Confidence Intervals) | ||||

| Divided by education | ||||

| Whites ≤high school vs. Whites >high school | 1.16 (0.75,1.80) | 1.58 (0.99,2.51) | 2.40 (1.31,4.41)** | 3.73 (2.10,6.61)*** |

| Blacks ≤high school vs. Blacks >high school | 1.37 (0.89,2.11) | 1.31 (0.85,2.02) | 1.46 (0.95,2.23) | 1.79 (0.99,3.25) |

| Hispanics ≤high school vs. Hispanics >high school | 1.57 (1.23,2.02)*** | 1.63 (1.25,2.11)*** | 2.60 (1.68,4.02)*** | 1.91(1.60,2.27)*** |

| Asians ≤high school vs. Asians >high school | 3.40 (2.20,5.25)*** | 2.58 (1.65,4.03)** | 11.57 (6.59,20.31)*** | 1.84 (0.71,4.79) |

| Divided by income | ||||

| Whites in poverty vs. Whites not in poverty | 2.22 (1.71,2.89)*** | 1.99 (1.53,2.60)*** | 3.34 (2.24,4.98)*** | 1.82 (1.27,2.59)** |

| Blacks in poverty vs. Blacks not in poverty | 1.95 (1.46,2.60)*** | 1.72 (1.30,2.29)*** | 1.46 (1.45,1.46)*** | 2.20 (1.48,3.28)*** |

| Hispanics in poverty vs. Hispanics not in poverty | 1.79 (1.37,2.34)*** | 1.61 (1.22,2.12)*** | 2.10 (1.53,2.88)*** | 1.55 (1.31,1.83)*** |

| Asians in poverty vs. Asians not in poverty | 2.02 (1.16,3.55)* | 1.92 (1.51,2.44)*** | 2.07 (0.96,4.46) | 1.62 (0.81,3.21) |

Note: ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; CERAD-WL = Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List; AFT = Animal Fluency Test

All models were adjusted for age, sex, place of birth, language use, marital status, health insurance, smoking, and alcohol intake, and accounted for NHANES sampling weight

* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001

Discussion

Findings from our study indicate that compared to Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites, older Asian Americans experienced the highest burden of physical functioning and memory impairment due to education disparity. Specifically, education disparity for ADL and IADL disability and memory impairment were largest among Asians compared to Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Income disparity for functional impairment did not significantly differ across the four racial/ethnic groups.

Our finding that education disparity affects health status in Asian Americans has also been reported in a recent study examining the association between education level and dementia risk in a large Asian American cohort study. The study found that older Asian Americans that attained a college degree had lower incidences of dementia, broadly consistent across different ethnicities and nativity status. Only Japanese Americans born outside the U.S. were found to have higher instances of dementia with a high level of education [27]. Prior research examining older adults in the U.S. have also found education as a protective measure against poor self-reported health. Another study examining data from NHANES found that older adults with lower educational attainment had stronger associations between lower cognitive functioning and mortality [28]. One explanation for the association between increased education and improved health status across the four racial/ethnic groups included is the cognitive reserve hypothesis. High levels of education may help to build cognitive reserve, changing aspects of the brain’s processing and structure in order to protect the individual from exhibiting age-related cognitive decline and pathology [29].

The high level of heterogeneity among Asians may help explain why the group exhibits the largest physical and memory impairment disparities due to education [30]. There are significant within-group disparities, including level of education, origin of immigration, level of social support, and quality of education among Asian Americans. For example, 27% of Japanese Americans are first-generation immigrants compared to 78% of Burmese Americans; and among those above age 25, 75% of Indian Americans have a bachelor’s degree compared to 15% and 18% of Bhutanese and Laotian Americans, respectively. The level of English proficiency is also predictably varied, with 38% of Burmese considered proficient in English compared to 85% of Japanese Americans [31]. This is largely due to individual reasons for immigration, as many new Burmese immigrants arrived within the last 15 years as refugees escaping internal conflicts in Myanmar, while many others immigrate in search of better education and career opportunities [32]. Those with limited English proficiencies experience many structural barriers to health care and as a result, are less likely to visit physicians or undergo preventative screening [33]. Studies have also shown that many risk factors related to cognitive impairment, including smoking, are widely ranged in the Asian American population, with lower education levels associated with a higher prevalence of smoking and a lower rate of cessation [34].

When examining income disparity, the level of physical and cognitive functioning disparities measured were more consistent across the four racial/ethnic groups. The ability to access and afford quality care is critical to maintaining or improving physical and cognitive functions into old age. As the United States provides health insurance (Medicaid) to low-income individuals, this may help explain the similar level of functional disparities found across the four groups.

Several limitations need to be acknowledged in this study. First, the cross‐sectional nature of the NHANES data does not allow us to determine the temporality between the independent variables and the outcomes. Second, a more comprehensive examination of Asian heterogeneity was restricted by the data collection limitations within NHANES. Efforts to further disaggregate Asian Americans into available subgroups, including country of birth and preferred language, resulted in sample size subgroups that were insufficient in achieving statistically significant results. While we have presented SES disparities as a source of Asian American health disparities, this is only part of the picture. Accounting for additional measures, including ethnicity, age of immigration, level of social support, and English proficiency, may help further explain the extent of these health disparities. Future work must examine different aspects contributing to Asian American heterogeneity and their effects on older adults' health status. Third, in the scope of our investigation, we analyzed education and income as representative indicators for SES. However, it is crucial to note that racial and ethnic disparities in cognitive and physical functioning impairment may not solely be attributed to these factors. Other individual- and community-level SES markers, including residential location (whether urban or rural), area deprivation, and neighborhood-built environment, could potentially exert influence as well. Future studies are needed to have a more in-depth exploration by employing a broader and multidimensional range of SES indicators to better elucidate the nuanced ways in which SES intersects with racial and ethnic disparities in cognitive and physical health outcomes. Finally, there are limited measures of cognitive assessment available in the NHANES. More comprehensive assessments of cognitive function are necessary for future studies.

Conclusion

This study provides empirical evidence that deepens our understanding of health equity for Asian American older adults. It also points to the importance of increased research to address the persistent Model Minority Myth and emphasize the heterogeneity and health disparities among older Asians in the US. In many prior studies on this topic, Asian American older adults have been left out of the data and narrative. The inclusion of Asians is especially important, as within the last two decades, the population has grown faster than any other racial or ethnic group in the US. The growing presence of Asians in the US, coupled with the historical absence of their representation in health disparity literature, emphasizes the importance to further investigate the breadth and depth of Asian American health experiences [35]. It is vital to build a more robust research infrastructure that caters to a further understanding of Asian American disparities, including in-depth examinations of their diverse cultural background, immigration status and history, country and context of migration, and the social and physical environment in which they live. In addition, more programs and services are needed to improve health status for individuals with low SES status to help alleviate disparities in cognitive and physical functioning.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

Concept and design of the study: Katherine Wang, Zheng Zhu, and Xiang Qi.

Data analysis: Katherine Wang, Zheng Zhu, and Xiang Qi.

Interpretation of data and critical revision for intellectual content: Katherine Wang, Zheng Zhu, and Xiang Qi.

Writing the final manuscript, final approval of version to be published: Katherine Wang, Zheng Zhu, and Xiang Qi.

Katherine Wang had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) datasets are publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of Centers of Diseases Control and Prevention. Researchers may obtain the datasets after sending a data user agreement to the NHANES team (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and all patients provided written informed consent. This project is the result of a secondary analysis of NHANES and is exempt from local IRB approval.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mobility is Most Common Disability Among Older Americans, Census Bureau Reports. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/archives/2014-pr/cb14-218.html#:~:text=Nearly%2040%20percent%20of%20people,difficulty%20in%20walking%20or%20climbing. Accessed 20 Mar 2023.

- 2.Manly JJ, Jones RN, Langa KM, et al. Estimating the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in the US: the 2016 health and retirement study harmonized cognitive assessment protocol project. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(12):1242–1249. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samper-Ternent R, Kuo YF, Ray LA, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS, Al SS. Prevalence of health conditions and predictors of mortality in oldest old Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter GG, Plassman BL, Burke JR, et al. Cognitive performance and informant reports in the diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia in African Americans and whites. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(6):445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng JH, Bierman AS, Elliott MN, Wilson RL, Xia C, Scholle SH. Beyond black and white: race/ethnicity and health status among older adults. Am J Manag Care. 2015;20(3):239–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melvin J, Hummer R, Elo I, Mehta N. Age patterns of racial/ethnic/nativity differences in disability and physical functioning in the United States. Demogr Res. 2014;31(17):497–510. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2016;12(3):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng C. Are Asian American employees a model minority or just a minority. J Appl Behav Sci. 1997;33(3):277–290. doi: 10.1177/0021886397333002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monte LM, Shin HB. 20.6 Million People in the U.S. Identify as Asian, native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/05/aanhpi-population-diverse-geographically-dispersed.html. Accessed 19 Mar 2023.

- 11.Harris B. Racial Inequality in the United States. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/racial-inequality-in-the-united-states. Accessed 18 Mar 2023

- 12.Kochhar R, Cilluffo A. Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/. Accessed 19 Mar 2023.

- 13.2020 Profile of Asian Americans Age 65 and Older. Services USDoHaH. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Profile%20of%20OA/AsianProfileReport2021.pdf. Accessed 18 Mar 2023.

- 14.Liu H, Hu T. Impact of socioeconomic status and health risk on fall inequality among older adults. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6):e4961–e4974. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States Aged 65 Years and Older: Population, Nativity, and Language. Vol. 1. https://www.napca.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/65-population-report-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2023.

- 16.Chan K, Marsack-Topolewski C. Ethnic and neighborhood differences in poverty and disability among older Asian Americans in New York City. Soc Work Public Health. 2022;37(3):258–273. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2021.2000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorkin DH, Nguyen H, Ngo-Metzger Q. Assessing the mental health needs and barriers to care among a diverse sample of Asian American older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):595–602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsoy E, Kiekhofer RE, Guterman EL, et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in timeliness and comprehensiveness of dementia diagnosis in California. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(6):657–665. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu B, Qi X. Addressing health disparities among older asian American populations: research, data, and policy. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2022;32(3):105–111. doi: 10.1093/ppar/prac015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National health and nutrition examination survey: plan and operations, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat 1. 2013;56:1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulose-Ram R, Burt V, Broitman L, Ahluwalia N. Overview of Asian American data collection, release, and analysis: national health and nutrition examination survey 2011–2018. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):916–921. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.2018 Poverty Guidelines. Office of the Assistant Secretary For Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references/2018-poverty-guidelines. Accessed 23 Mar 2023.

- 23.Data from: national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2022.

- 24.Bailey RL, Jun S, Murphy L, et al. High folic acid or folate combined with low vitamin B-12 status: potential but inconsistent association with cognitive function in a nationally representative cross-sectional sample of US older adults participating in the NHANES. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(6):1547–1557. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo HK, Leveille SG, Yu YH, Milberg WP. Cognitive function, habitual gait speed, and late-life disability in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. Gerontology. 2007;53(2):102–110. doi: 10.1159/000096792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivastava VK, Giles DEA. Seemingly Unrelated Regression Equations Models: Estimation and Inference. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1987.

- 27.Hayes-Larson E, Ikesu R, Fong J, et al. Association of education with dementia incidence stratified by ethnicity and nativity in a cohort of older Asian American individuals. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231661. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adjoian M, Dodds L, Rundek T, et al. Associations between cognitive functioning and mortality in a population-based sample of older united states adults: differences by sex and education. J Aging Health. 2022;34(6–8):905–915. doi: 10.1177/08982643221076690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng X, D'Arcy C. Education and dementia in the context of the cognitive reserve hypothesis: a systematic review with meta-analyses and qualitative analyses. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drouhot LG, Garip F. What’s behind a racial category? Uncovering heterogeneity among Asian Americans through a data-driven typology. Russell Sage Foundation J Soc Sci. 2021;7(2):22–25. doi: 10.7758/RSF.2021.7.2.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budiman A, Ruiz N. Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/. Accessed 10 Mar 2023.

- 32.The Rise of Asian Americans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/. Accessed 10 Mar 2023.

- 33.Ponce NA, Hays RD, Cunningham WE. Linguistic disparities in health care access and health status among older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):786–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An N, Cochran SD, Mays VM, McCarthy WJ. Influence of American acculturation on cigarette smoking behaviors among Asian American subpopulations in California. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):579–587. doi: 10.1080/14622200801979126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanaya AM, Hsing AW, Panapasa SV, et al. Knowledge gaps, challenges, and opportunities in health and prevention research for Asian Americans, native Hawaiians, and pacific islanders: a report from the 2021 national institutes of health workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(4):574–589. doi: 10.7326/M21-3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) datasets are publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of Centers of Diseases Control and Prevention. Researchers may obtain the datasets after sending a data user agreement to the NHANES team (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).