Abstract

Anthracyclines are associated with cardiotoxic manifestations that are mainly dose-dependent, with onset varying from a few days to many years after stopping treatment. Frequent monitoring for toxic manifestations, early detection, cessation of anthracycline use and appropriate treatment is the key to preventing morbidity and mortality. Complete heart block with doxorubicin use in Hodgkin’s lymphoma is rarely reported, and is a severe toxic manifestation necessitating withdrawal or changing of regimen to etoposide + bleomycin + vinblastine + dacarbazine (EBVD), as in this case.

Keywords: MEDICAL ONCOLOGY, Heart failure, DRUG-RELATED SIDE EFFECTS AND ADVERSE REACTIONS, Case Reports, Antineoplastic agents

Background

Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a malignancy of the lymphatic system originating from B-cells and is further characterised by nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma or classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma.1 Epidemiological searches link the disease to the younger population (25–35 years).1 A regimen consisting of doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD) is the standard treatment regimen for advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma, with a 3-year progression-free survival rate and overall survival rate of 85.7% and 97.2%, respectively.2 Doxorubicin in the ABVD regimen is one of the most widely prescribed anticancer drugs. The cytotoxic properties of the molecule were first identified in the mid 19th century and approved for clinical use in 1963. Like other chemotherapeutic agents, doxorubicin causes adverse events that may involve multiple organ systems including the liver, kidneys and heart. Cardiotoxicity caused by doxorubicin is largely dose-dependent, and the effects have been noted even after 10–15 years of cessation of treatment. The exact mechanism of cardiotoxicity is still unclear. The most commonly reported toxic cardiac manifestations are reduced ventricular function leading to heart failure, sinus bradycardia and sinus tachycardia as part of decompensated heart failure.3 Table 1 shows some of the reported cases of doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity, with demographic details, dose, time to develop symptoms and treatment.

Table 1.

Reported cases of Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) induced cardiac toxicity, authors, demographic details, dose, time for the development of symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and recovery time

| Case no | Study | Drug | Age (years) | Gender | Dose of anthracycline derivative (cumulative) | Time to develop symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment | Recovery time |

| 1 | Xie et al 12 | Doxorubicin | 26 | F | NS | Immediately | Bradycardia | Atropine | 2 days |

| 2 | Okura et al 13 | Epirubicin | 42 | F | 780 mg/m2 | 5 months | Heart failure | Oxygen, diuretics and vasodilators | 18 days |

| 3 | Kumar et al 18 | Doxorubicin | 57 | F | 300 mg/m2 | 17 years | Cardiomyopathy, hypertension | β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, digoxin and diuretic | 12 months |

| 4 | Chong et al 14 | Doxorubicin | 35 | F | 450 mg/m2 | 2 months | Severe biventricular failure, multi-organ congestion | Inotropic and vasopressor support |

Death |

| 5 | Silva et al 17 | Doxorubicin | 79 | F | 550 mg/m2 | 6 months | Heart failure, arrhythmias | ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and loop diuretics | NS |

| 6 | Malatesta et al 19 | Epirubicin | 38 (pregnant) |

F | 90 mg/ m2 | NS | Fetal cardiac toxicity in twin A | Corticosteroids | Death of fetus |

| 7 | Cotteret et al 20 | Doxorubicin | 42 (pregnant) |

F | 50 mg/m2 | On the same day of the last cycle | Complicated pregnancy, minor LV dysfunction in first neonate | Prednisone | NS |

| 8 | Farina et al 21 | Doxorubicin | 37 | M | NS | Immediately | T-wave inversion, LVEF 20% | Doxorubicin withdrawal, metoprolol succinate, carvedilol, lisinopril | 2.5 months |

| 9 | Koitabashi et al 22 | Epirubicin | 70 | F | 400 mg/m2 | After the last cycle | Tachycardia, heart failure, LVEF 24% | Diuretics, dobutamine and carperitide | 14 months |

| 10 | Kuruc et al 23 | Doxorubicin | 37 | F | 240 mg/m2 | 2 years | LVEF 25%, cardiomyopathy | Beta-blocker, diuretics and antihypertensives | 14 days |

ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The second drug in the ABVD regimen, bleomycin, is another first-line drug used in various cancer regimens including testicular cancer. However, a review of the literature suggests that the toxic effects of bleomycin are mainly on the respiratory system,4 while toxic cardiac manifestations such as hypotension, pericarditis, acute substernal chest pain, coronary artery disease, myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, cerebral vascular accident and Raynaud’s phenomenon are very rare.5

Vinblastine used in the ABVD regimen is a plant-based alkaloid derived from Catharanthus rosea. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown haematological adverse events directly linked with the use of this drug.6 Vinblastine has been associated with causing myocardial injury and decreased life span in vivo and in vitro rat models, but no such manifestation has been observed in human myocardial cells.7

Dacarbazine, widely used for lymphatic malignancies and malignant melanoma, is metabolised by the liver into its intermediate metabolite, 3-methyl-(triazine-1-yl) imidazole-4-carboxamide (MTIC).8 The adverse drug reaction (ADR) of this alkylating agent has not been linked to cardiotoxicity according to the available literature.

Case presentation

A man in his 30s with no comorbidities diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma on an ABVD regimen developed severe fatigue NYHA Class III and giddiness after two cycles of chemotherapy. His heart rate was 38–40 bpm, blood pressure 90/60 mm Hg and arterial oxygen saturation was 98%. His systemic examination was unremarkable except for a low heart rate.

Investigations

Twelve-lead ECG showed severe sinus bradycardia (40 bpm), while 24-hour Holter monitoring revealed sinus bradycardia (lowest rate 38 bpm), intermittent complete heart block (CHB) and junctional escape rhythm at 40–45 bpm and frequent junctional ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) (figure 1). Other investigations including a two-dimensional echocardiogram (2D-ECHO), complete blood count, fasting lipid profile, renal and liver, thyroid function tests, serum electrolytes, calcium and magnesium were normal. A provisional diagnosis of drug-induced CHB, possibly due to doxorubicin, was made. The Naranjo ADR scale9 gave a score of 9 for doxorubicin, inferring a definite ADR. Hence, the doxorubicin-based ABVD regimen was discontinued and a non-doxorubicin-based regimen was planned for the next scheduled cycle.

Figure 1.

Holter strip showing runs of junctional escape rhythm with intermittent VPCs after two cycles of doxorubicin-based ABVD regimen. Red arrows indicate junctional beats, blue arrows indicate dissociated P waves at around 30 bpm, green arrow shows aberrantly conducted sinus beat and black arrow indicates VPC. VPC, ventricular premature complex; ABVD, Adriamycin (doxorubicin) + bleomycin + vinblastine + dacarbazine.

Treatment

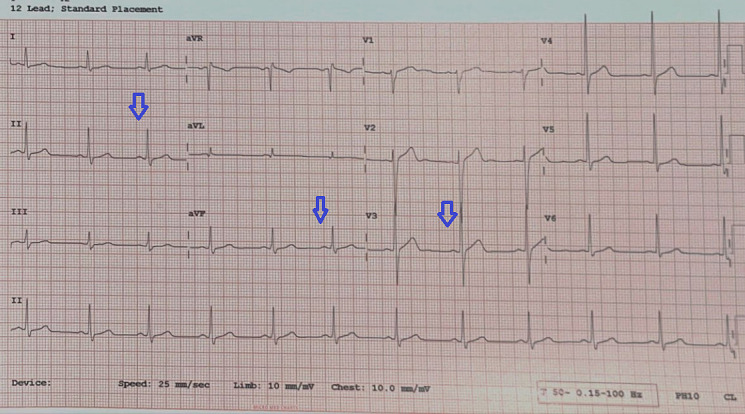

The patient was treated symptomatically with an oral etophylline and theophylline combination, orciprenaline, intravenous (IV) atropine as required, and dopamine infusion for bradycardia and hypotension for 48 hours. After 4 days of treatment the patient became haemodynamically stable and his doxorubicin-based regimen was stopped. He was discharged with oral orciprenaline until the next follow-up visit. He continued to have bradycardia (heart rate 55–60 bpm) for the next 3 weeks but without symptoms. Figure 2 shows the ECG at the 6-week follow-up with recovery to sinus rhythm. Subsequently, the patient was changed to EBVD (etoposide + bleomycin + vinblastine + dacarbazine) regimen for Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a possible need to restart the ABVD regimen if there was no response and to manage possible recurrence of CHB with temporary (TPM) or permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation. Figure 3 shows the normal 12-lead ECG recorded from the patient during the early evaluation stage of the disease (malignancy).

Figure 2.

Twelve-lead ECG strip showing recovery of sinus rhythm at a rate of 70 bpm with no VPCs after stopping the doxorubicin-based ABVD regimen. Blue arrows show regular sinus activity. VPC, ventricular premature complex; ABVD, Adriamycin (doxorubicin) + bleomycin + vinblastine + dacarbazine.

Figure 3.

Twelve-lead ECG recorded during the early evaluation stage of the disease (malignancy) from the patient showing normal findings.

Outcome and follow-up

At 1 year the patient had a complete response to chemotherapy with the EBVD regimen and was asymptomatic without any recurrence of CHB.

Discussion

Anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens are widely used to treat breast cancer, lymphomas and solid childhood tumours that can cause cardiotoxicity during and after treatment.8 Doxorubicin was one of the first anthracyclines used in clinical practice.10 A significant ADR associated with doxorubicin and other anthracyclines is the development of dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure, increasing mortality in cancer survivors.11 The incidence of heart failure is dose-dependent and can occur early after initiation of treatment or may emerge decades after cumulative exposure.12 Other common toxic cardiac manifestations include sinus tachycardia (with reduced left ventricular function), angina and atrial fibrillation.11–13 Uncommon but severe complications reported from anthracycline usage are cardiogenic shock, tachyarrhythmias and bradycardia.14 The exact mechanism by which anthracyclines contribute to cardiac toxicity or heart failure is not entirely understood. However, some of the proposed mechanisms include impairment of mitochondrial function by increasing iron accumulation and ROS (reactive oxygen species) production and altering calcium homeostasis by inducing calcium leakage from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, impairing cardiac contractility and relaxation.15 16 The latest and most accepted theory suggests a dose-dependent injury to cardiomyocytes initiated through inhibition of topoisomerase 2-β, leading to the initiation of apoptosis and depletion of mitochondrial biosynthesis.16

The damage caused by anthracyclines on the heart is acute and reversible in most cases if diagnosed and treated early. Some common drugs used to manage symptoms include ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and diuretics in patients who experienced heart failure. Inotropes and vasopressors are also used in patients with biventricular failure and cardiogenic shock, and atropine is used in patients who experienced bradycardia.12 14 17 However, according to a literature review, the discontinuation of anthracycline therapy after cardiotoxic symptoms is a primary and significant intervention in limiting the damage in acute management stages.7

Although adverse events following the administration of anthracyclines varied in variety and severity, none of the case reports seem to implicate the drug with CHB, making this adverse reaction extremely rare. Certain risk factors such as older age and multiple comorbid conditions predispose to the development of cardiotoxicity. However, no such comorbidities were present in the patient reported here, emphasising the need for close monitoring for toxic cardiac manifestations irrespective of age and associated comorbidities. Even though beta-blockers are said to prevent the incidence of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction in patients on anthracycline derivatives, in the reported patient they are contraindicated. In 2007 the Food and Drug Administration approved dexrazoxane (DRZ), a cardioprotective-chemoprotective drug, to mitigate anthracycline-related toxicity.16 Adding DRZ to the ABVD regimen may help to dilute the risk of cardiotoxicity in the reported patient if the doxorubicin-based regimen becomes necessary to manage advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Patient’s perspective.

Despite the difficulties I went through, I am very happy that my illness has thrown some light on the possible unreported side effects of a particular drug which was used on me. However, I am thankful to the team of doctors who treated me despite the limited options they had. I will be very happy to see this new finding getting published. (Patient Mr N)

Learning points.

Anthracyclines are an important group of chemotherapeutic agents with significant cardiac toxicity, and frequent evaluation for adverse drug reactions is essential to avoid complications.

Commonly reported cardiotoxic manifestations with anthracycline use are left ventricular or biventricular dysfunction, sinus tachycardia, sinus bradycardia, rarely cardiogenic shock and arrhythmias, which often occur with multiple other comorbid conditions.

Sinus node suppression, complete heart block with a junctional escape rhythm and atrioventricular dissociation are rarely reported in the literature, especially in young patients with no comorbidities and a relatively short duration of exposure to doxorubicin as in this case.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ManjappaGpet

Contributors: MM: conceptualised and wrote the manuscript and also treated the patient. KPK: involved in treating the patient and data collection. LKA: data collection, editing the manuscript and contribution to the table. YC: data collection, critical review and editing. PK: critical review and editing of the manuscript. MM is guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Union for International Cancer Control, World Health Organization . 2014 review of cancer medicines on the WHO list of essential medicines. Hodgkin's lymphoma (adult); 2014.

- 2. Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET-CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2016;374:2419–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1510093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al-Malky HS, Al Harthi SE, Osman A-MM. Major obstacles to doxorubicin therapy: cardiotoxicity and drug resistance. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2020;26:434–44. 10.1177/1078155219877931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raphael MJ, Lougheed MD, Wei X, et al. A population-based study of pulmonary monitoring and toxicity for patients with testicular cancer treated with bleomycin. Curr Oncol 2020;27:291–8. 10.3747/co.27.6389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Floyd JD, Nguyen DT, Lobins RL, et al. Cardiotoxicity of cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7685–96. 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chong CD, Logothetis CJ, Savaraj N, et al. The correlation of vinblastine pharmacokinetics to toxicity in testicular cancer patients. J Clin Pharmacol 1988;28:714–8. 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilson MA, Schuchter LM. Chemotherapy for melanoma. Cancer Treat Res 2016;167:209–29. 10.1007/978-3-319-22539-5_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McGowan JV, Chung R, Maulik A, et al. Anthracycline chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2017;31:63–75. 10.1007/s10557-016-6711-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gilchrist SC, Barac A, Ades PA, et al. Cardio-oncology rehabilitation to manage cardiovascular outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e997–1012. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for Cancer Treatments and Cardiovascular Toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2768–801. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xie Z, Wu W, Xing H, et al. Bradycardia associated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin administration: a case report. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2017;24:128–30. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2015-000817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okura Y, Kawasaki T, Kanbayashi C, et al. A case of epirubicin-associated cardiotoxicity progressing to life-threatening heart failure and splenic thromboembolism. Intern Med 2012;51:1355–60. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chong EG, Lee EH, Sail R, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: a case report and review of literature. World J Cardiol 2021;13:28–37. 10.4330/wjc.v13.i1.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nebigil CG, Désaubry L. Updates in anthracycline-mediated cardiotoxicity. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1262. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henriksen PA. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: an update on mechanisms, monitoring and prevention. Heart 2018;104:971–7. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teixeira da Silva F, Morais Passos R, Esteves A, et al. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity in a patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a case report. Cureus 2020;6. 10.7759/cureus.11038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar S, Marfatia R, Tannenbaum S. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy 17 years after chemotherapy. Tex Heart Inst J 20122012;39:424–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Framarino-dei-Malatesta M, Perrone G, Giancotti A, et al. Epirubicin: a new entry in the list of fetal cardiotoxic drugs? Intrauterine death of one fetus in a twin pregnancy. Case report and review of literature. BMC Cancer 2015;15:951. 10.1186/s12885-015-1976-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cotteret C, Pham Y-V, Marcais A, et al. Maternal ABVD chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma in a dichorionic diamniotic pregnancy: a case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:231. 10.1186/s12884-020-02928-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farina K, Kalac M, Kim S. Acute cardiomyopathy following a single dose of doxorubicin in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2021;27:1011–5. 10.1177/1078155220953886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koitabashi N, Ohyama Y, Tateno R, et al. Reversible cardiomyopathy after epirubicin administration. Int Heart J 2015;56:466–8. 10.1536/ihj.14-416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuruc JC, Durant-Archibold AA, Motta J, et al. Development of anthracycline-induced dilated cardiomyopathy due to mutation on LMNA gene in a breast cancer patient: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2019;19:169. 10.1186/s12872-019-1155-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.