Abstract

Binding of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein gp120 to both CD4 and one of several chemokine receptors (coreceptors) permits entry of virus into target cells. Infection of tissues may establish latent viral reservoirs as well as cause direct pathologic effects that manifest as clinical disease such as HIV-associated dementia. We sought to identify the critical coreceptors recognized by HIV-1 tissue-derived strains as well as to correlate these coreceptor preferences with site of infection and dementia diagnosis. To reconstitute coreceptor use, we cloned HIV-1 envelope V3 sequences encoding the primary determinants of coreceptor specificity from 13 brain-derived and 6 colon-derived viruses into an isogenic (NL4-3) viral background. All V3 recombinants utilized the chemokine receptor CCR5 uniformly and efficiently as a coreceptor but not CXCR4, BOB/GPR15, or Bonzo/STRL33. Other receptors such as CCR3, CCR8, and US28 were inefficiently and variably used as coreceptors by various envelopes. CCR5 without CD4 present did not allow for detectable infection by any of the tested recombinants. In contrast to the pathogenic switch in coreceptor specificity frequently observed in comparisons of blood-derived viruses early after HIV-1 seroconversion and after onset of AIDS, the characteristics of these V3 recombinants suggest that CCR5 is a primary coreceptor for brain- and colon-derived viruses regardless of tissue source or diagnosis of dementia. Therefore, tissue infection may not depend significantly on viral envelope quasispeciation to broaden coreceptor range but rather selects for CCR5 use throughout disease progression.

Entry into target cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) depends critically on binding of the viral envelope glycoprotein (gp120) to both CD4 and a cellular coreceptor (31). Recently, both definitive and putative coreceptors have been identified as members of the G-protein-coupled chemokine receptor family that confer onto cells susceptibility to infection by various isolates of HIV-1.

HIV-1 coreceptor utilization is the principal determinant of cellular tropism. While macrophage-tropic viruses characteristically employ the β-chemokine receptor CCR5 (3, 15, 21, 29, 30), T-cell line-tropic viruses use the α-chemokine receptor CXCR4 (38). Changes in tropism and coreceptor specificity correlate with progression of AIDS. Early after infection, primary viral isolates from the blood are homogeneous in envelope sequence and are largely or exclusively CCR5 using or macrophage-tropic (18, 85, 110, 111). As AIDS develops, approximately 50% of individuals experience a switch in cellular tropism to a more heterogeneous population in the blood that carries CXCR4-using or T-cell line-tropic viruses (18, 98–100). The importance of CCR5 in mediating HIV-1 infection was established by the natural occurrence of the CCR5Δ32 loss-of-function mutation. Persons homozygous for CCR5Δ32 display resistance to initial HIV-1 infection, while heterozygotes demonstrate a slower progression to AIDS after seroconversion (19, 45, 60, 77, 84). The contribution of CXCR4 to pathogenesis has also been highlighted by studies in various models of HIV-1 immunodepletion (41, 71).

High levels of viral replication are associated with genetic evolution in vivo. This allows for production of a range of quasispecies with distinct envelopes that have been hypothesized to use a broader range of coreceptors to infect a larger number of host cell types (103). Accordingly, a number of HIV-1 strains that can utilize alternate chemokine receptors in addition to CCR5 and CXCR4 under various in vitro conditions have been described. These receptors include CCR2b (29), CCR3 (15, 43), CCR8 (50), BOB/GPR15 (22, 37), Bonzo/STRL33 (22, 59), GPR1 (37), V28/CX3CR1 (82), ChemR23 (83), leukotriene B4 receptor (69), Apj (14, 32), and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-encoded US28 (72). However, the significance of each alternate coreceptor in HIV-1 disease remains undefined.

Previous work that explored coreceptor use and disease progression focused mainly on primary blood isolates (18). Viral entry into tissues may also be a principal determinant of HIV-1 dissemination and pathogenesis (58), and studies have begun to examine this issue (26, 88). Tissue infection may allow for establishment of viral reservoirs that function as separate replication sites from blood. Viruses isolated from the central nervous system (CNS) (1, 6, 10, 27, 35, 46, 55, 70, 76, 87, 107), bowel (8), and other tissues (6, 27, 35, 48, 87, 112) possess genetic and phenotypic differences compared to viruses isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. In addition, various cell types that reside in tissues and express alternate coreceptors may play critical roles in disease progression (5, 20, 36, 40, 53, 66, 81, 97, 102). It is unknown whether a separate evolution of coreceptor use also occurs in viruses replicating in tissues. Preliminary coreceptor specificity studies have also implicated tissue-invasive strains as direct contributors to clinical disease. Such a paradigm exists for the CNS and brain, where neurotropic strains are hypothesized to infect specifically macrophages, microglia (74, 96, 102), and other components of neural tissue (5, 97). Neurovirulent strains evolving from these may subsequently trigger the development of HIV-associated dementia (HIVD) (51, 61, 62).

The V3 hypervariable region of the gp120 envelope protein carries the main determinants of both cellular tropism (11, 12, 47, 86, 89, 105, 106) and coreceptor use (15, 16, 94, 108). Transfer of a V3 loop from one virus into a distinct HIV-1 background typically retains the coreceptor profile of the V3 donor (15, 94). In addition, single amino acid changes in the V3 loop can drastically alter coreceptor specificities (94). As a result, V3 recombinants allow not only for mapping determinants of tropism but also for a methodology of screening viral coreceptor preferences. Although other regions of gp120 may influence coreceptor recognition in some settings (13, 92), relatively few unpassaged HIV-1 strains have been isolated from tissues as molecular clones that carry full-length envelope sequences (26, 88).

Thus, the most feasible approach to screening in vivo coreceptor specificity is to use the V3 and flanking sequences previously identified by postmortem PCR analyses of brain and colon tissue from AIDS patients (27, 76). Isolates from brain tissue were chosen to identify selection pressures present in the CNS viral reservoir (10, 54) that may affect development of HIVD. Isolates from colon tissue were chosen for comparison to explore the possible existence of an alternate viral reservoir that imposes distinct selection pressures. Using an isogenic proviral backbone, we constructed V3 recombinants that carried the specific coreceptor usages of the original clinical isolates. Subsequent functional analyses allowed us to identify the biologically relevant coreceptors that mediate tissue infection of the brain and colon and then correlate coreceptor specificity with site of infection (brain versus colon) and the diagnosis of HIVD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

293T (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) and human osteosarcoma (GHOST) indicator (provided by D. Littman) cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Mediatech, Herndon, Va.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bio-Products, Calabasas, Calif.) and 100 μg of penicillin-streptomycin (Mediatech) per ml. The parental GHOST clone 34 stably maintaining human CD4 expression was under constant selection with G418 (500 μg/ml; Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) and hygromycin B (100 μg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). GHOST transfectants stably expressing a specific coreceptor (CCR5, CXCR4, BOB/GPR15, or Bonzo/STRL33) were under additional selection with puromycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). COS-7 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were routinely cultured in Iscove’s medium (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg of penicillin-streptomycin per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Mediatech). COS-7 transfections were carried out with LipofectAMINE (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All infections were performed in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium–10% FBS–100 μg of penicillin-streptomycin per ml.

Plasmids and construction of recombinant proviruses.

Molecular clones pYU-2, pNL4-3, and pNL-Luc-E−R− (17) (the NL4-3 provirus backbone with a luciferase reporter gene insertion) were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Expression plasmids encoding CCR3 (pcDNA3-CCR3p), HCMV US28 (pRC/CMV-US28), ADA gp160 envelope (ADApEnv), CD4 (pCD4neo), and CCR5 (pCMVFCCR5) were previously described (4, 42, 72, 82, 105). The expression plasmid encoding CCR8 (pAW-CCR8F) was provided by I. Charo.

Plasmids (p2-1, p10-1, p14-2, p15-2, p17-2, p19-1, p26-4, p26-5, p48-1, p54-1, p59-1, and p62-1) encoding chimeric NL4-3 provirus with a 428-bp insertion (StuI-NheI) that includes the V3 and portions of the C2 and C3 regions of brain-derived gp120 sequences were constructed as previously described (76). Plasmid p4-14 (11) encoding NL4-3 provirus (with a 16-bp polylinker MluI-NheI inserted in place of the 126-bp region coding portions of gp120 V3-C3 region) was used as the isogenic viral backbone for constructing additional V3 replacements based on published amino acid sequences (27, 74, 76). V3 nucleotide sequences were deduced by inserting degenerate codons most prevalent in the mammalian genome. An oligonucleotide pair representing the deduced V3 sequence for brain-derived 5-1 (Fig. 1) along with deduced 5′ C3 sequence for NL4-3 was annealed as described by the manufacturer (Oligos, Etc., Wilsonville, Oreg.) and contained restriction site overhangs 5′ MluI-3′ NheI with unique sites ApaI, SmaI, and XbaI inserted internally. The annealed oligonucleotides were cloned initially into a holding vector. After digestion of both p4-14 and the holding vector containing 5-1 with MluI and NheI and ligation of 5-1 insert with p4-14 backbone, the full-length chimeric provirus p5-1 was used as the parental vector for construction of other proviruses (p4-7, p4-8, p4-9, p6-2, p6-3, and p6-4) since it carried convenient restriction sites. Oligonucleotide pairs 4-7 and 4-8 were annealed (5′ SmaI-3′ XbaI), inserted into a holding vector, digested (SmaI/XbaI), and ligated with the linearized p5-1 backbone (SmaI/XbaI) to make p4-7 and p4-8 proviruses. Oligonucleotide pairs 4-9, 6-2, 6-3, and 6-4 were annealed (5′ MluI-3′ XbaI), inserted into a holding vector, digested (MluI/XbaI), and ligated with the linearized p5-1 (MluI/XbaI) to make p4-9, p6-2, p6-3, and p6-4 proviruses. Inserted sequences were verified by ABI Prism Dye terminator cycle sequencing (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.).

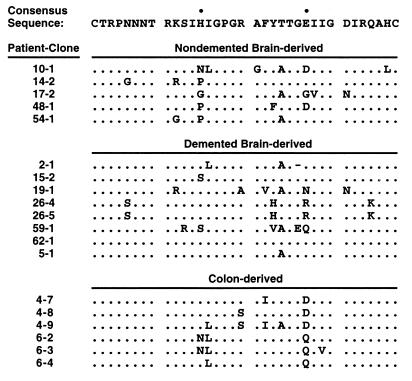

FIG. 1.

Three groups of V3 loop amino acid sequences, isolated by postmortem PCR from brain tissue and colon tissue of AIDS patients, show homology to a macrophage-tropic consensus sequence (11) deduced from blood-borne strains. A period denotes identity with the consensus, while a dash denotes deletion. Bullets denote V3 positions 13 and 25 in the consensus sequence. Sequences of colon-derived viruses and demented brain-derived virus (5-1) were isolated from three AIDS patients (27). Remaining brain-derived virus sequences were isolated from 11 AIDS patients diagnosed with HIVD (76). Recombinant virus 59-1 was previously termed 59-3. Recombinant viruses 26-4 and 26-5 (previously termed 26-1 and 26-2, respectively) have identical V3 sequences as noted above but vary at gp120 position 335 in the C3 region, as described elsewhere (76).

Preparation of virus stocks.

To prepare experimental V3 recombinant viruses and full-length control viruses (YU-2 and NL4-3) for spreading infections, proviral plasmids were transfected into 293T cells by the CaPO4 method (Promega, Madison, Wis.) as previously described (42). Recombinant viral stocks were sterile filtered (0.45-μm-pore-size-filters) and harvested after both 36- and 60-h incubations. The p24Gag concentration was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; New England Nuclear Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.), and stocks greater than 1,500 ng/ml were used for infections. Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) strain Mac239 (550 ng of p27Gag per ml) (52) was provided by R. Grant.

To prepare pseudotype virus carrying the luciferase gene (Luc+) with the ADA envelope for single-round infections, pNL-Luc-E−R− (2 μg/well) was cotransfected with ADApEnv (2 μg/well) in 293T cells growing in six-well plates as previously described (22). Pseudotype Luc+ viruses carrying the tissue-derived V3 envelopes were similarly prepared by cotransfecting pNL-Luc-E−R− (3 μg/well) along with full-length proviral plasmids described above (1 μg/well). Pseudotype recombinant virus stocks greater than 110 ng/ml were used for infections.

Coreceptor utilization assay for spreading infection.

GHOST cell lines expressing CD4 alone or in combination with CCR5 or CXCR4 were plated in 96-well plates (7,000 cells/well) and infected as previously described (93). Cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and medium was replaced 12 h after infection. Day 0 and day 8 supernatant aliquots (10 μl) were removed for secreted p24Gag measurements. Cell lines were infected with equivalent inocula of recombinant virus normalized by utilization of CCR5 as a coreceptor (Fig. 2). The amount of recombinant virus added to different GHOST cell lines never varied for a given infection. Infection of GHOST cell lines stably expressing CD4 with BOB or Bonzo was assessed as described above except that cells were plated (20,000 cells/well) in 12-well plates. The amount of added recombinant virus never varied between these cell lines for a given infection. To detect infection by SIV Mac239, secreted p27Gag concentration was measured by ELISA (Coulter, Miami, Fla.). For all infections, microscopic observations of syncytium formation were also recorded up to 14 days after infection.

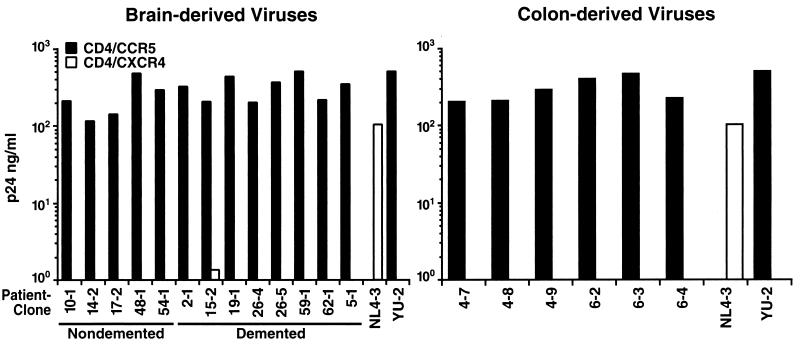

FIG. 2.

Efficient and uniform use of CCR5 but not CXCR4 as a coreceptor by all V3 recombinant viruses. HIV-1 YU-2 (CCR5 dependent) and NL4-3 (CXCR4 dependent) were used as controls. Displayed values are representative of day 8 supernatant p24 concentrations seen in two separate infections performed with these recombinants.

Coreceptor utilization assay for single-round infection.

COS-7 cells were plated in six-well plates and transfected with pCMVFCCR5 alone, pCD4neo alone, or pCD4neo in combination with pCMVFCCR5, pcDNA3-CCR3p, pAW-CCR8F, or pRC/CMV-US28 as previously described (4). After 24 h, cells were infected with pseudotype Luc+ recombinant viruses. V3 recombinant viruses were normalized by utilization of CCR5 as a coreceptor (Fig. 3A), and amounts of added virus never varied between cell lines in a specific transfection/infection experiment. After 48 h, luciferase expression was assessed by enzymatic activity (light units/milligram of protein) as previously described (65), as instructed by the manufacturer (Analytical Luminescence Laboratories, Sparks, Md.).

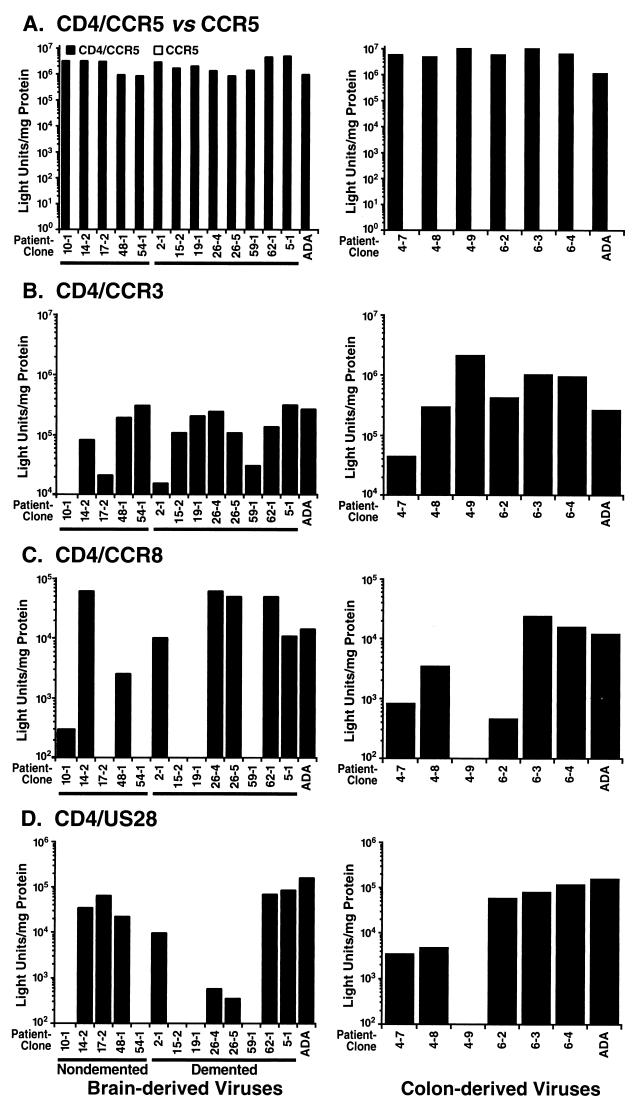

FIG. 3.

Variable use of CCR3, CCR8, and US28 as coreceptors by all V3 recombinant viruses compared to use of CCR5. (A) Comparison of infections by pseudotype V3 recombinant viruses of COS-7 cells transiently expressing CCR5 with and without CD4. No tested recombinant displayed infection mediated by CCR5 in the absence of CD4. (B) Infection of COS-7 cells transiently expressing CD4 and CCR3. Recombinant virus 10-1 displayed no detectable infection mediated by CCR3. (C) Infection of COS-7 cells transiently expressing CD4 and CCR8. Recombinant viruses 17-2, 54-1, 15-2, 19-1, 59-1, and 4-9 displayed no detectable infection mediated by CCR8. (D) Infection of COS-7 cells transiently expressing CD4 and US28. Recombinant viruses 10-1, 54-1, 15-2, 19-1, 59-1, and 4-9 displayed no detectable infection mediated by US28. In all studies, Luc+ pseudotype HIV-1 carrying the ADA envelope was used as a positive control. Background readings were obtained from infection of COS-7 cells transiently expressing CD4 without coreceptor and ranged from 0 to 5,000 light units/mg of protein. Displayed values were normalized by subtraction of background signals, and they are representative of the relative ratios of coreceptor specificity seen in two to three separate infections performed with Luc+ pseudotype recombinant viruses.

RESULTS

Envelope sequences from brain and colon tissue isolates of HIV-1 inserted into the NL4-3 provirus.

Previous studies demonstrated that V3 loop insertion into an alternate viral backbone such as NL4-3 can reconstitute the tropism (47, 106) and coreceptor phenotype (15, 16, 94) of the V3 donor. For the present study, we surveyed the literature for V3 loop amino acid sequences derived from colon and brain samples of AIDS patients for whom HIVD diagnosis was documented (27, 76). To correlate coreceptor preferences with presence of HIVD, we chose five sequences from five nondemented patients and eight sequences from seven demented patients for analysis. To correlate coreceptor preferences with site of infection, we selected six colon sequences from two patients for comparison to the brain-derived recombinants (Fig. 1).

All brain- and colon-derived V3 sequences showed homology to a macrophage-tropic consensus sequence (76). Furthermore, all samples carried a moderately positive net V3 loop charge (ranging from +2 to +6), in contrast to the highly positive net charge commonly observed in CXCR4-using V3 loops (49). Of note, V3 loop position 13 appeared to favor proline in nondemented subjects compared to a consensus histidine in demented patients when a larger collection than this listed set was considered (76). In addition, all colon-derived viral sequences carried either an aspartate or a glutamine residue at V3 loop position 25 rather than the consensus glutamate. In the present study, DNA sequences representing the selected V3 loops with adjacent conserved sequences (for details, see Materials and Methods) were inserted into the NL4-3 backbone. The resulting chimeric viruses were used to test definitively the coreceptor utilization of tissue-specific HIV-1 isolates.

Efficient use of CCR5, but not of CXCR4, as coreceptors for cellular entry.

Human osteosarcoma (GHOST) cell lines stably expressing human CD4/CCR5 or human CD4/CXCR4 were infected with each recombinant virus in vitro. Detection of p24Gag by ELISA was performed on the culture supernatants at days 0 and 8 after infection as a marker of spreading infection. Since it demands multiple rounds of infection, such an assay is most biologically pertinent and interpretable. All V3 recombinants representing brain-derived (nondemented and demented) and colon-derived viruses displayed uniformly high replication in GHOST CCR5/CD4 cells (Fig. 2). By day 8, microscopic examination revealed syncytia in all cultures. Conversely, no brain- or colon-derived recombinant propagated significant spreading infection in GHOST CXCR4/CD4 cells, and no syncytia were observed at any time in the cultures (Fig. 2). The parental NL4-3 virus, known to employ CXCR4 as a coreceptor, infected these cells robustly. Therefore, all of the experimental recombinant viruses displayed efficient CCR5 coreceptor use, while none demonstrated detectable use of CXCR4.

Nearly uniform failure to use either BOB/GPR15 or Bonzo/STRL33 as an alternate coreceptor for cellular entry.

We sought to determine if BOB/GPR15 or Bonzo/STRL33, two orphan chemokine receptor-like proteins identified as putative HIV-1 coreceptors (22, 59), could be used for cellular entry. We employed SIV Mac239 (52) as a positive control since it uses both coreceptors more efficiently than some HIV-1 strains (data not shown) and is able to establish more robust spreading infections in culture (as detected in a p27 ELISA). The supernatant p24 measurements of infection of GHOST cells stably expressing CD4/BOB or CD4/Bonzo were compared to Mac239 p27 levels after days 0 and 10. One brain-derived recombinant (2-1) inefficiently employed BOB/GPR15 to sustain spreading infection (4 ng of p24 per ml measured at day 10), but no syncytia were observed by day 14. In contrast, no other V3 recombinant representing a brain-derived virus (nondemented or demented) or colon-derived virus detectably used BOB/GPR15 or Bonzo/STRL33 for spreading infection (data not shown).

Inefficient and variable use of CCR3, CCR8, and US28 as alternate coreceptors for cellular entry.

In contrast to CCR5, CXCR4, BOB/GPR15, and Bonzo/STRL33, the chemokine receptors CCR3, CCR8, and HCMV US28 presented several technical challenges to studying their role as coreceptors. Importantly, our initial experiments revealed that HIV-1 strains previously reported to recognize these alternate coreceptors (15) may not utilize them efficiently for cellular entry. Thus, we used an enzymatic assay in which COS-7 cells transiently expressing CD4 and a putative coreceptor were infected with pseudotype viruses carrying the envelopes of interest and the luciferase reporter gene (22). Viral infection was quantitated by measuring entry of the pseudotype Luc+ recombinant strains through readout of luciferase enzymatic activity. This allowed for a sensitive assessment of coreceptor specificity that was not achieved in a p24 spreading infection assay.

In corroboration of the results from the spreading infection assay, all of the V3 recombinants representing the brain- and colon-derived strains efficiently used CCR5 for cellular entry (Fig. 3A), generating signals in the range of 106 to 107 light units/mg of protein. Since several recent studies have identified CD4-independent infection by a neurovirulent strain of SIV (33) and select strains of HIV-2 (34, 79), viral infection in the presence of CCR5 without CD4 was also assessed. None of the brain- or colon-derived recombinants infected cells detectably in the absence of CD4 expression (Fig. 3A).

Substantially lower and more variable luciferase signals were observed in single-round infections of COS-7 cells expressing CD4/CCR3 compared with CD4/CCR5 (Fig. 3B). Whereas all recombinants used CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry, one (10-1) did not detectably use CCR3, two (17-2, 2-1) slightly recognized CCR3, while others (for example, 14-2, 54-1; 26-4, 62-1, and 6-4) measurably used CCR3, albeit less efficiently than CCR5. Of those that used CCR3, nearly all recombinants generated luciferase counts less than 106 light units/mg of protein, which were typically 90 to 99% lower than comparable readings seen in the CCR5-dependent infections. Importantly, comparison of V3 recombinants representing brain-derived viruses from nondemented and demented patients revealed no distinct pattern of CCR3 use, with both groups displaying a spectrum of viral phenotypes with regard to CCR3. Similarly variable phenotypes of CCR3 use were observed in the colon-derived collection compared with the brain-specific set.

Inefficient and variable infections were also observed with the putative coreceptor CCR8 after single-round infection (Fig. 3C). While some brain-derived recombinants from the nondemented (14-2 and 48-1) and demented (2-1, 26-4, 26-5, 62-1, and 5-1) groups exhibited modest infection, other recombinants from both brain collections (10-1, 17-2, 54-1, 15-2, 19-1, and 59-1) showed little infection using CCR8 as a coreceptor. Similarly, only one colon-derived recombinant (4-9) failed to use CCR8, while the others recognized CCR8 to a slight degree. Signals from the CCR8 infections were less than 105 light units/mg of protein and at least 90% lower than those for CCR5 infections.

Similar results of low and variable infectivity were obtained with HCMV US28 (Fig. 3D). Because it is encoded by HCMV rather than the human host genome, US28 has been proposed to enhance HIV-1 disease progression during HCMV coinfection commonly seen in AIDS patients (7). Inefficient infection through US28 was observed with recombinants from certain nondemented (14-2, 17-2, and 48-1) and demented (2-1, 26-4, 26-5, 62-1, and 5-1) patients, while other strains (10-1, 54-1, 15-2, 19-1, and 59-1) from both groups displayed no cellular entry. Similar to the CCR8 profile, one colon-derived recombinant (4-9) did not use US28, while the rest of the set recognized it to a small degree. Nearly all recombinant viral infections mediated by US28 exhibited luciferase readings less than 105 light units/mg of protein and at least 90% lower than those from CCR5.

Further comparison of the virus infection profiles revealed no uniform correlation among particular coreceptor specificities in any recombinant collection. One recombinant (10-1) exhibited virtually no use of any of the alternate coreceptors tested, while others (14-2, 48-1, 2-1, 62-1, 5-1, 4-7, and 6-2) used all three alternate coreceptors to some degree. Moreover, recombinants such as 26-5 recognized CCR3 and CCR8 but only slightly US28, while 17-2 recognized CCR3 and US28 but not CCR8, and 4-9 recognized CCR3 but not CCR8 or US28. Thus, these V3 recombinant viruses did not display a simple and predictable pattern in their coreceptor specificity profiles. Rather, they all demonstrated variable alternate coreceptor patterns compared to their highly efficient and uniform utilization of CCR5.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to characterize coreceptor preferences among V3 recombinants representing brain- and colon-derived HIV-1 isolates as well as to correlate HIVD diagnosis and site of infection with these coreceptor recognition profiles. We determined that all demented and nondemented brain-specific recombinants and colon-specific recombinants utilized CCR5 efficiently but did not use CXCR4, BOB/GPR15, or Bonzo/STRL33 detectably by spreading infection. In addition, these recombinants recognized CCR3, CCR8, and US28 relatively inefficiently and variably as coreceptors as assayed by sensitive single-round infection methods.

Incomplete eradication of HIV-1 after triple-drug therapy has been attributed in part to the hypothesized separation and relative protection of tissue reservoirs of latent virus from viral populations residing in blood (54, 101, 107). Previous comparisons of V3 envelope sequences (9, 24, 27, 35, 48, 55, 56, 76, 78, 101) and, in some cases, cellular target specificities (26, 74, 88) of unpassaged, tissue-derived viruses sought to define a pattern(s) necessary for viral propagation in tissues different from that observed in blood. In the present study, we examined V3 recombinant viruses carrying some sequence variability within the tissue-specific V3 loops, particularly at positions 13 and 25 (see Results). Brain-derived HIV-1 strains such as those represented here are thought to replicate in vivo as an isolated population, while colon-derived strains may not evolve separately from blood-borne viruses, based on a recent phylogenetic analysis (101). Despite these differences, we discovered a pattern of uniform CCR5 use that indicated a higher degree of functional similarity among tissue-specific viruses than initially suspected. Indeed, additional sequence comparisons of these recombinants with the V3 loops of known CCR5-using strains (64) revealed extensive similarities at other potentially critical amino acid positions. Although we were unable to detect the presence of a distinct viral reservoir present in colon tissue based on a lack of differences in coreceptor specificity, the uniformity of CCR5 utilization did indicate the probable existence of a common selective pressure in multiple tissues. These results strengthen the claim that antigen-presenting cells, such as microglia, macrophages, and follicular dendritic cells, which commonly reside in tissues and express CD4 and CCR5, are the principal cells that establish and maintain virus populations in all tissues (23, 53, 74, 91, 95, 102).

The nearly absent usage of CXCR4, BOB/GPR15, and Bonzo/STRL33 suggests the inability of these coreceptors to mediate tissue infection despite their expression on certain tissue-resident cell types (22, 57, 109). While no evidence has directly demonstrated the in vivo importance of BOB/GPR15 and Bonzo/STRL33, the role of CXCR4 in pathogenesis has been described for certain viruses residing in the blood (41, 71). From our results, it is reasonable to postulate that unidentified pressures in the brain and colon select against viral use of CXCR4, perhaps in part by the exclusion of infected CXCR4-expressing T cells from trafficking into these tissues.

While most of the brain- and colon-derived recombinants were found to recognize CCR3 as a coreceptor to a variable degree, all could use CCR5 better than CCR3, with most generating at least a 10-fold difference in infection levels. Previously, it was demonstrated that the level of HIV-1 infection mediated by CCR3 varies with the level of coreceptor expression, and inefficient use of CCR3 (15, 82) was attributed to the difficulty of maintaining high levels of expression in cell culture (73). For our analyses, we used the best-reported expression construct (pcDNA3-CCR3p) (82) and a sensitive enzymatic readout to increase our ability to detect CCR3-dependent entry. Conceivably, the presence of at least some degree of CCR3 recognition in nearly all tested recombinants may point to a positive selective pressure in the brain and colon in light of recent evidence of high expression levels in vivo of CCR3 in the CNS and lamina propria of the colon (109). Nonetheless, the global efficiency of CCR5 utilization strongly highlights CCR5 as a predominant coreceptor in mediating tissue-specific infections.

Recently, it was reported that certain HIV-1 strains isolated from brain-derived cells can use CCR8 as a coreceptor (50). In addition, US28 has been implicated in HIV-1 pathogenesis through HCMV opportunistic coinfections in various tissues (39, 63, 67, 90). Our results indicated that neither CCR8 nor HCMV US28 supports efficient infection by any of the recombinants tested. Furthermore, the variability in infection efficiency among different recombinants suggested that no consistent selection pattern is imposed on viruses based on CCR8 or HCMV US28 use. Of note, all colon-derived recombinants from patient 6 did display relatively uniform use of US28. It is tempting to speculate that this coreceptor specificity may be related to the presence of HCMV in the colon, perhaps causing the mucosal atrophy and inflammation observed in this patient (28). However, in light of the rest of our results and the fact that US28 is expressed only during the HCMV lytic growth phase in vitro (104), it is unlikely that US28 has major in vivo significance by itself as a coreceptor for infection of the brain or colon.

We also sought to correlate coreceptor preferences with the presence of HIVD (74, 76, 96). Evidence that both supports and argues against the hypothesis that CCR3 is preferentially recognized by neurotropic and/or neurovirulent viruses (43, 88) that may dictate dementia development has been presented. We observed uniform coreceptor recognition of CCR5 along with inefficient and variable use of alternate putative coreceptors including CCR3 by all demented and nondemented brain-derived V3 recombinants. Importantly, comparison of coreceptor use by brain-derived recombinants with that by presumably nonneurotropic colon-derived recombinants yielded no significant difference in relative specificity profiles. These results imply that a change or selection for CCR3 or other coreceptor specificity is not sufficient to trigger HIVD development. In addition, our results suggest that CD4-independent infection may not contribute to progression of dementia. Alternatively, it has been postulated that HIV-1 may use CCR3 in combination with CCR5 or other coreceptors to enhance infection of the brain (43). However, our initial experiments showed no significant difference in levels of infection among cells transiently expressing CD4 with both CCR5 and CCR3 and cells expressing CD4 with CCR5 alone (data not shown). Collectively, these observations argue against alternate coreceptors or viral CD4 independence as key factors in the pathogenesis of HIVD.

Our strategy employing an isogenic viral backbone allowed us to normalize postentry events, such as viral replication and transcription rates that may vary among different primary isolates. However, it also limited our ability to test all possible determinants of coreceptor specificity and cellular tropism of these clinical strains. Although the V3 loop primarily controls coreceptor specificity, other envelope regions such as V1/2 can be important with certain viruses for specific coreceptor utilization (44, 68, 80). To address this issue, we obtained recombinant NL4-3 proviruses carrying regions V1 to V3 of five of the original brain-derived viruses, including two from the demented group and three from the nondemented group (75). Comparable coreceptor utilization profiles were achieved for both the V1-V3 strains and the matched V3 strains upon testing CCR5, CXCR4, BOB/GRRI5, Bonzo/STRL33, CCR3, CCR8, and US28. Therefore, these results further substantiate the claim that usage patterns derived from the V3 recombinants constructed for this study approximate the coreceptor specificities of the original primary tissue-derived isolates.

It is also conceivable that coreceptor recognition and infection of primary cells in vivo are modulated by parameters different from those that allow for in vitro infections (25). However, of the 19 recombinant strains, 13 had previously been shown to infect macrophages in culture (74), demonstrating that the efficiency of CCR5 use by these viruses correlates well with macrophage tropism. Furthermore, previous reports have emphasized that different coreceptor assays display a range of intrinsic sensitivities that can lead to conflicting results in specificity (2, 13, 88). Therefore, differences in the various assays must be noted in order to compare accurately coreceptor utilization data among different studies.

Despite these caveats, the consistent patterns and large differences in coreceptor specificity among these representative recombinants strengthen our conclusion of the predominant role of CCR5 in tissue invasion. Therefore, the coreceptor switch from CCR5 to CXCR4 characteristically seen in blood-borne viruses does not seem typical of tissue-specific isolates. Absence of a predictable coreceptor evolution pattern also suggests that other pathogenic events in the brain are responsible for causing HIVD. It remains an intriguing possibility that other recently described putative coreceptors, such as V28/CX3CR1 (79, 82) and Apj (14, 32), that are highly expressed in the brain play a role in development of HIVD. Alternatively, differences observed in the V3 loop sequence between isolates from demented and nondemented patients may have an impact on HIVD progression by differentially altering production of soluble neurotoxic factors by infected macrophages (75), perhaps through alterations in signal transduction that are independent of tropism determination. Nonetheless, the results of the present study should provide optimism for the potential effectiveness of drug therapies aimed at preventing CCR5-mediated cellular entry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marc Alizon, Israel Charo, Robert Grant, Beatrice Hahn, Nathaniel Landau, Dan Littman, Malcolm Martin, and Stephen Peiper for reagents, Yang He for technical assistance, Gary Howard for editorial assistance, and John Carroll for preparation of the figures. We also thank Ninan Abraham, Robert Atchison, Michael Penn, and Jonathan Snow for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the J. David Gladstone Institutes and by Pfizer, Inc. (M.A.G.). S.Y.C. was supported by the NIH Medical Scientist Training Program and the UCSF Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, R.F.S. was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, C.P. was supported by the Medical Research Council of Canada, and S.L.G. was supported by the Bank of America-Giannini Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ait-Khaled M, McLaughlin J, Johnson M, Emery V. Distinct HIV-1 long terminal repeat quasispecies present in nervous tissues compared to that in lung, blood and lymphoid tissues of an AIDS patient. AIDS. 1995;9:675–683. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib G, Berger E, Murphy P, Pease J. Determinants of HIV-1 coreceptor function on CC chemokine receptor 3. Importance of both extracellular and transmembrane/cytoplasmic regions. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20420–20426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atchison R E, Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Franci C, Digilio L, Charo I F, Goldsmith M A. Multiple extracellular elements of CCR5 and HIV-1 entry: dissociation from response to chemokines. Science. 1996;274:1924–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagasra O, Lavi E, Bobroski L, Khalili K, Pestaner J, Tawadros R, Pomerantz R. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 in the central nervous system of infected individuals: identification by the combination of in situ polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. AIDS. 1996;10:573–585. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball J, Holmes E, Whitwell H, Desselberger U. Genomic variation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1): molecular analyses of HIV-1 in sequential blood samples and various organs obtained at autopsy. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:67–79. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-4-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balter M. Does a common virus give HIV a helping hand? Science. 1997;276:1794. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett S, Barboza A, Wilcox C, Forsmark C, Levy J. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains recovered from the bowel of infected individuals. Virology. 1991;182:802–809. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90621-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang J, Jozwiak R, Wang B, Ng T, Ge Y, Bolton W, Dwyer D, Randle C, Osborn R, Cunningham A, Saksena N. Unique HIV type 1 V3 region sequences derived from six different regions of brain: region-specific evolution within host-determined quasispecies. AIDS Res Hum Retrovirol. 1998;14:25–30. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng-Mayer C, Weiss C, Seto D, Levy J. Isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from the brain may constitute a special group of the AIDS virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8575–8579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Perryman S. Macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus isolates from different patients exhibit unusual V3 envelope sequence homogeneity in comparison with T-cell-tropic isolates: definition of critical amino acids involved in cell tropism. J Virol. 1992;66:6547–6554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6547-6554.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Perryman S. Mapping of independent V3 envelope determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 macrophage tropism and syncytium formation in lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:9055–9059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.9055-9059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho M, Lee M, Carney M, Berson J, Doms R, Martin M. Identification of determinants on a dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein that confer usage of CXCR4. J Virol. 1998;72:2509–2515. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2509-2515.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choe H, Farzan M, Konkel M, Martin K, Sun Y, Marcon L, Cayabyab M, Berman M, Dorf M, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The orphan seven-transmembrane receptor Apj supports the entry of primary T-cell-line-tropic and dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:6113–6118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6113-6118.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cocchi F, DeVico A, Garzino-Demo A, Cara A, Gallo R C, Lusso P. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp 120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-medicated blockade of infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connor R, Chen B, Choe S, Landau N. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikemts R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O’Brien S J Hemophilia Growth and Development Study; Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study; Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study; San Francisco City Cohort; ALIVE Study. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delezay O, Koch N, Yahi N, Hammache D, Tourres C, Tamalet C, Fantini J. Co-expression of CXCR4/fusin and galactosylceramide in the human intestinal epithelial cell line HT-29. AIDS. 1997;11:1311–1318. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199711000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng H, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani V, Littman D R. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997;388:296–299. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickson D, Mattiace L, Kure K, Hutchins K, Lyman W, Brosnan C. Microglia in human disease, with an emphasis on acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Lab Investig. 1991;64:135–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Stefano M, Wilt S, Gray F, Dubois-Dalcq M, Chiodi F. HIV type 1 V3 sequences and the development of dementia during AIDS. AIDS Res Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12:471–476. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dittmar M, McKnight A, Simmons G, Clapham P, Weiss R. HIV-1 tropism and co-receptor use. Nature. 1997;385:495–496. doi: 10.1038/385495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dittmar M, Simmons G, Donaldson Y, Simmonds P, Clapham P, Schulz T, Weiss R. Biological characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones derived from different organs of an AIDS patient by long-range PCR. J Virol. 1997;71:5140–5147. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5140-5147.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaldson Y, Bell J, Holmes E, Hughes E, Brown H, Simmonds P. In vivo distribution and cytopathology of variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 showing restricted sequence variability in the V3 loop. J Virol. 1994;68:5991–6005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5991-6005.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donaldson Y, Bell J, Ironside J, Brettle R, Robertson J, Busuttil A, Simmonds P. Redistribution of HIV outside the lymphoid system with onset of AIDS. Lancet. 1994;343:383–385. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2β as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Souza M, Harden V. Chemokines and HIV-1 second receptors. Nat Med. 1996;2:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edinger A, Hoffman T, Sharron M, Lee B, Yi Y, Choe W, Kolson D, Mitrovic B, Zhou Y, Faulds D, Collman R, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R, Doms R. An orphan seven-transmembrane domain receptor expressed widely in the brain functions as a coreceptor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1998;72:7934–7940. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7934-7940.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edinger A, Mankowski J, Doranz B, Margulies B, Lee B, Rucker J, Sharron M, Hoffman T, Berson J, Zink M, Hirsch V, Clements J, Doms R. CD4-independent, CCR5-dependent infection of brain capillary endothelial cells by a neurovirulent simian immunodeficiency virus strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14742–14747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endres M J, Clapham P R, Marsh M, Ahuja M, Davis Turner J, McKnight A, Thomas J F, Stoebenau-Haggarty B, Choe S, Vance P J, Wells T N C, Power C A, Sutterwala S S, Doms R W, Landau N R, Hoxie J A. CD4-independent infection by HIV-2 is mediated by fusin/CXCR4. Cell. 1996;87:745–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein L, Kuiken C, Blumberg B, Hartman S, Sharer L, Clement M, Goudsmit J. HIV-1 V3 domain variation in brain and spleen of children with AIDS: tissue-specific evolution within host-determined quasispecies. Virology. 1991;180:583–590. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90072-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fantini J, Yahi N, Chermann J. Human immunodeficiency virus can infect the apical and basolateral surfaces of human colonic epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9297–9301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farzan M, Choe H, Martin K, Marcon L, Hoffmann W, Karlsson G, Sun Y, Barrett P, Marchand N, Sullivan N, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. Two orphan seven-transmembrane segment receptors which are expressed in CD4-positive cells support simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Exp Med. 1997;186:405–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finkle C, Tapper M, Knox K, Carrigan D. Coinfection of cells with the human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus in lung tissues of patients with AIDS. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:735–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghorpade A, Xia M, Hyman B, Persidsky Y, Nukuna A, Bock P, Che M, Limoges J, Gendelman H, Mackay C. Role of beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of monocytes and microglia. J Virol. 1998;72:3351–3361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3351-3361.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glushakova S, Grivel J, Fitzgerald W, Sylwester A, Zimmerberg J, Margolis L. Evidence for the HIV-1 phenotype switch as a causal factor in acquired immunodeficiency. Nat Med. 1998;4:346–349. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldsmith M A, Warmerdam M T, Atchison R E, Miller M D, Greene W C. Dissociation of the CD4 downregulation and viral infectivity enhancement functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef. J Virol. 1995;69:4112–4121. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4112-4121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He J, Chen Y, Farzan M, Choe H, Ohagen A, Gartner S, Busciglio J, Yang X, Hofmann W, Newman W, Mackay C R, Sodroski J, Gabuzda D. CCR3 and CCR5 are co-receptors for HIV-1 infection of microglia. Nature. 1997;385:645–649. doi: 10.1038/385645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman T, Stephens E, Narayan O, Doms R. HIV type I envelope determinants for use of the CCR2b, CCR3, STRL33, and APJ coreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11360–11365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang Y, Paxton W A, Wolinsky S M, Neumann A U, Zhang L, He T, Kang S, Ceradini D, Jin Z, Yazdanbakhsh K, Kunstman K, Erikson D, Dragon E, Landau N R, Phair J, Ho D D, Koup R A. The role of a mutant CCR5 allele in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1996;2:1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes E, Bell J, Simmonds P. Investigation of the dynamics of the spread of human immunodeficiency virus to brain and other tissues by evolutionary analysis of sequences from the p17gag and env genes. J Virol. 1997;71:1272–1280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1272-1280.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang S S, Boyle T J, Lyerly H K, Cullen B R. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science. 1991;71:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1905842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Itescu S, Simonelli P, Winchester R, Ginsberg H. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains in the lungs of infected individuals evolve independently from those in peripheral blood and are highly conserved in the C-terminal region of the envelope V3 loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11378–11382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang S. HIV-1-co-receptors binding. Nat Med. 1997;3:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jinno A, Shimizu N, Soda Y, Haraguchi Y, Kitamura T, Hoshino H. Identification of the chemokine receptor TER1/CCR8 expressed in brain-derived cells and T cells as a new coreceptor for HIV-1 infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:479–502. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson R, Glass J, McArthur J, Chesebro B. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus in brains of demented and nondemented patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:392–395. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kestler H W, III, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koenig S, Gendelman H, Orenstein J, Dal Canto M, Pezeshkpour G, Yungbluth M, Janotta F, Aksamit A, Martin M, Fauci A. Detection of AIDS virus in macrophages in brain tissue from AIDS patients with encephalopathy. Science. 1986;233:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.3016903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolson D, Lavi E, Gonzalez-Scarano F. The effects of human immunodeficiency virus in the central nervous system. Adv Virus Res. 1998;50:1–47. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Korber B, Kunstman K, Patterson B, Furtado M, McEvilly M, Levy R, Wolinsky S. Genetic differences between blood- and brain-derived viral sequences from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: evidence of conserved elements in the V3 region of the envelope protein of brain-derived sequences. J Virol. 1994;68:7467–7481. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7467-7481.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuiken C, Goudsmit J, Weiller G, Armstrong J, Hartman S, Portegies P, Dekker J, Cornelissen M. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 sequences from patients with and without AIDS dementia complex. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:175–180. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lavi E, Strizki J, Ulrich A, Zhang W, Fu L, Wang Q, O’Connor M, Hoxie J, Gonzalez-Scarano F. CXCR-4 (fusin), a co-receptor for the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), is expressed in the human brain in a variety of cell types, including microglia and neurons. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1035–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levy J. Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:183–289. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.183-289.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liao F, Alkhatib G, Peden K, Sharma G, Berger E A, Farber J M. STRL33, a novel chemokine receptor-like protein, functions as a fusion cofactor for both macrophage-tropic and T cell line-tropic HIV-1. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2015–2023. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, McDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mankowski J, Flaherty M, Spelman J, Hauer D, Didier P, Amedee A, Murphey-Corb M, Kirstein L, Munoz A, Clements J, Zink M. Pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis: viral determinants of neurovirulence. J Virol. 1997;71:6055–6060. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6055-6060.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mankowski J, Spelman J, Ressetar H, Strandberg J, Laterra J, Carter D, Clements J, Zink M. Neurovirulent simian immunodeficiency virus replicates productively in endothelial cells of the central nervous system in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1994;68:8202–8208. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8202-8208.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mentec H, Leport C, Marche C, Harzic M, Vilde J. Cytomegalovirus colitis in HIV-1-infected patients: a prospective research in 55 patients. AIDS. 1994;8:461–467. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Milich L, Margolin B, Swanstrom R. Patterns of amino acid variability in NSI-like and SI-like V3 sequences and a linked change in the CD4-binding domain of the HIV-1 Env protein. Virology. 1997;239:108–118. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Molden J, Chang Y, You Y, Moore P, Goldsmith M. A Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded cytokine homolog (vIL-6) activates signaling through the shared gp130 receptor subunit. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19625–19631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moyer M, Gendelman H. HIV replication and persistence in human gastrointestinal cells cultured in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:499–504. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nelson J, Reynolds-Kohler C, Oldstone M, Wiley C. HIV and HCMV coinfect brain cells in patients with AIDS. Virology. 1988;165:286–290. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Owen S, Ellenberger D, Rayfield M, Wiktor S, Michel P, Grieco M, Gao F, Hahn B, Lal R. Genetically divergent strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 use multiple coreceptors for viral entry. J Virol. 1998;72:5425–5432. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5425-5432.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Owman C, Garzino-Demo A, Cocchi F, Popovic M, Sabirsh A, Gallo R. The leukotriene B4 receptor functions as a novel type of coreceptor mediating entry of primary HIV-1 isolates into CD4-positive cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9530–9534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pang S, Vinters H, Akashi T, O’Brien W, Chen I. HIV-1 env sequence variation in brain tissue of patients with AIDS-related neurologic disease. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:1082–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Picchio G, Gulizia R, Wehrly K, Chesebro B, Mosier D. The cell tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 determines the kinetics of plasma viremia in SCID mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood leukocytes. J Virol. 1998;72:2002–2009. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2002-2009.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pleskoff O, Treboute C, Brelot A, Heveker N, Seman M, Alizon M. Identification of a chemokine receptor encoded by human cytomegalovirus as a cofactor for HIV-1 entry. Science. 1997;276:1874–1878. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ponath P, Qin S, Post T, Wang J, Wu L, Gerard N, Newman W, Gerard C, Mackay C. Molecular cloning and characterization of a human eotaxin receptor expressed selectively on eosinophils. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2437–2448. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Power C, McArthur J, Johnson R, Griffin D, Glass J, Dewey R, Chesebro B. Distinct HIV-1 env sequences are associated with neurotropism and neurovirulence. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;202:89–104. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79657-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Power C, McArthur J, Nath A, Wehrly K, Mayne M, Nishio J, Langelier T, Johnson R, Chesebro B. Neuronal death induced by brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope genes differs between demented and nondemented AIDS patients. J Virol. 1998;72:9045–9053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9045-9053.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Power C, McArthur J C, Johnson R T, Griffin D E, Glass J D, Perryman S, Chesebro B. Demented and nondemented patients with AIDS differ in brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope sequences. J Virol. 1994;68:4643–4649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4643-4649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rana S, Besson G, Cook D, Rucker J, Smyth R, Yi Y, Turner J, Guo H, Du J, Peiper S, Lavi E, Samson M, Libert F, Liesnard C, Vassart G, Doms R, Parmentier M, Collman R. Role of CCR5 in infection of primary macrophages and lymphocytes by macrophage-tropic strains of human immunodeficiency virus: resistance to patient-derived and prototype isolates resulting from the Δccr5 mutation. J Virol. 1997;71:3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3219-3227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reddy R, Achim C, Sirko D, Tehranchi S, Kraus F, Wong-Staal F, Wiley C. Sequence analysis of the V3 loop in brain and spleen of patients with HIV encephalitis. AIDS Res Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12:477–482. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reeves J, McKnight A, Potempa S, Simmons G, Gray P, Power C, Wells T, Weiss R, Talbot S. CD4-independent infection by HIV-2 (ROD/B): use of the 7-transmembrane receptors CXCR-4, CCR-3, and V28 for entry. Virology. 1997;231:130–134. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ross T, Cullen B. The ability of HIV type 1 to use CCR-3 as a coreceptor is controlled by envelope V1/V2 sequences acting in conjunction with a CCR-5 tropic V3 loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7682–7686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rubbert A, Combadiere C, Ostrowski M, Arthos J, Dybul M, Machado E, Cohn M, Hoxie J, Murphy P, Fauci A, Weissman D. Dendritic cells express multiple chemokine receptors used as coreceptors for HIV entry. J Immunol. 1998;160:3933–3941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rucker J, Edinger A L, Sharron M, Samson M, Lee B, Berson J F, Yi Y, Margulies B, Collman R G, Doranz B J, Parmentier M, Doms R W. Utilization of chemokine receptors, orphan receptors, and herpesvirus-encoded receptors by diverse human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:8999–9007. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.8999-9007.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Samson M, Edinger A, Stordeur P, Rucker J, Verhasselt V, Sharron M, Govaerts C, Mollereau C, Vassart G, Doms R, Parmentier M. ChemR23, a putative chemoattractant receptor, is expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages and is a coreceptor for SIV and some primary HIV-1 strains. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1689–1700. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1689::AID-IMMU1689>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C-M, Saragosti S, Lapoumeroulie C, Cognaux J, Forceille C, Muyldermans G, Verhofstede C, Burtonboy G, Georges M, Imai T, Rana S, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Doms R W, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schuitemaker H, Koot M, Kootstra N A, Dercksen M W, De Goede R E Y, van Steenwijk R P, Lange J M A, Schattenkerk J, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus populations. J Virol. 1992;66:1354–1360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1354-1360.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharpless N, O’Brien W, Verdin E, Kufta C, Chen I, Dubois-Dalcq M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tropism for brain microglial cells is determined by a region of the Env glycoprotein that also controls macrophage tropism. J Virol. 1992;66:2588–2593. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2588-2593.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sheehy N, Desselberger U, Whitwell H, Ball J. Concurrent evolution of regions of the envelope and polymerase genes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during zidovudine (AZT) therapy. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1071–1801. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-5-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shieh J, Albright A, Sharron M, Gartner S, Strizki J, Doms R, Gonzalez-Scarano F. Chemokine receptor utilization by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates that replicate in microglia. J Virol. 1998;72:4243–4249. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4243-4249.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shioda T, Levy J, Cheng-Mayer C. Small amino acid changes in the V3 hypervariable region of gp120 can affect the T-cell-line and macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9434–9438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Skolnik P, Pomerantz R, de la Monte S, Lee S, Hsiung G, Foos R, Cowan G, Kosloff B, Hirsch M, Pepose J. Dual infection of retina with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:361–372. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90659-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith P, Meng G, Shaw G, Li L. Infection of gastrointestinal tract macrophages by HIV-1. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:72–77. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smyth R, Yi Y, Singh A, Collman R. Determinants of entry cofactor utilization and tropism in a dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate. J Virol. 1998;72:4478–4484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4478-4484.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Speck R, Penn M, Wimmer J, Esser U, Hague B, Kindt T, Atchison R, Goldsmith M. Rabbit cells expressing human CD4 and human CCR5 are highly permissive for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1998;72:5728–5734. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5728-5734.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Speck R F, Chesebro B, Atchison R E, Wehrly K, Charo I F, Goldsmith M A. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J Virol. 1997;71:7136–7139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7136-7139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spiegel H, Herbst H, Niedobitek G, Foss H-D, Stein H. Follicular dendritic cells are a major reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in lymphoid tissues facilitating infection of CD4+ T-helper cells. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Strizki J, Albright A, Sheng H, O’Connor M, Perrin L, Gonzalez-Scarano F. Infection of primary human microglia and monocyte-derived macrophages with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: evidence of differential tropism. J Virol. 1996;70:7654–7662. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7654-7662.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takahashi K, Wesselingh S, Griffin D, McArthur J, Johnson R, Glass J. Localization of HIV-1 in human brain using polymerase chain reaction/in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:705–711. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tersmette M, de Goede R, Al B, Winkel I, Gruters R, Cuypers H, Huisman H, Miedema F. Differential syncytium-inducing capacity of human immunodeficiency virus isolates: frequent detection of syncytium-inducing isolates in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. J Virol. 1988;62:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2026-2032.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tersmette M, Gruters R A, de Wolf F, de Goede R E Y, Lange J M A, Schellekens P T A, Goudsmit J, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Evidence for a role of virulent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) variants in the pathogenesis of AIDS: studies on sequential HIV isolates. J Virol. 1989;63:2118–2125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2118-2125.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tersmette M, Lange J, de Goede R, de Wolf F, Eeftink-Schattenkerk J, Schellekens P, Coutinho R, Huisman J, Goudsmit J, Miedema F. Association between biological properties of human immunodeficiency virus variants and risk for AIDS and AIDS mortality. Lancet. 1989;i:983–985. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.van’t Wout A, Ran L, Kuiken C, Kootstra N, Pals S, Schuitemaker H. Analysis of the temporal relationship between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasispecies in sequential blood samples and various organs obtained at autopsy. J Virol. 1998;72:488–496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.488-496.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Watkins B, Dorn H, Kelly W, Armstrong R, Potts B, Michaels F, Kufta C, Dubois-Dalcq M. Specific tropism of HIV-1 for microglial cells in primary human brain cultures. Science. 1990;249:549–553. doi: 10.1126/science.2200125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weiss R. HIV receptors and the pathogenesis of AIDS. Science. 1996;272:1885–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Welch A, McGregor L, Gibson W. Cytomegalovirus homologs of cellular G protein-coupled receptor genes are transcribed. J Virol. 1991;65:3915–3918. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3915-3918.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Westervelt P, Gendelman H, Ratner L. Identification of a determinant within the human immunodeficiency virus 1 surface envelope glycoprotein critical for productive infection of primary monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3097–3101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Westervelt P, Trowbridge D, Epstein L, Blumberg B, Li Y, Hahn B, Shaw G, Price R, Ratner L. Macrophage tropism determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vivo. J Virol. 1992;66:2577–2582. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2577-2582.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wong J, Ignacio C, Torriani F, Havlir D, Fitch N, Richman D. In vivo compartmentalization of human immunodeficiency virus: evidence from the examination of pol sequences from autopsy tissues. J Virol. 1997;71:2059–2071. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2059-2071.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsett A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang L, He T, Talal A, Wang G, Frankel S, Ho D. In vivo distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus/simian immunodeficiency virus coreceptors: CXCR4, CCR3, and CCR5. J Virol. 1998;72:5035–5045. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5035-5045.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang L, MacKenzie P, Cleland A, Holmes E, Brown A, Simmonds P. Selection for specific sequences in the external envelope protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon primary infection. J Virol. 1993;67:3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3345-3356.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 in patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhu T, Wang N, Carr A, Nam D S, Moor-Jankowski R, Cooper D A, Ho D D. Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in blood and genital secretions: evidence for viral compartmentalization and selection during sexual transmission. J Virol. 1996;70:3098–3107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3098-3107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]