Abstract

Purpose:

Clinical patterns and the associated optimal management of acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade are poorly understood.

Experimental Design:

All cases of metastatic lung cancer treated with PD-(L)1 blockade at Memorial Sloan Kettering were reviewed. In acquired resistance (complete/partial response per RECIST, followed by progression), clinical patterns were distinguished as oligo (OligoAR, ≤ 3 lesions of disease progression) or systemic (sAR). We analyzed the relationships between patient characteristics, burden/location of disease, outcomes, and efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

Results:

Of 1,536 patients, 312 (20%) had an initial response and 143 developed AR (9% overall, 46% of responders). OligoAR was the most common pattern (80/143, 56%). Baseline tumor mutational burden, depth of response, and duration of response were significantly increased in oligoAR compared to sAR (P < 0.001, P = 0.03, P = 0.04, respectively), while baseline PD-L1 and tumor burden were similar. Post-progression, oligoAR was associated with improved overall survival (median 28 vs. 10 months, P < 0.001) compared to sAR. Within oligoAR, post-progression survival was greater among patients treated with locally-directed therapy (e.g. radiation, surgery; HR 0.41, p = 0.039). 58% of patients with oligoAR treated with locally-directed therapy alone are progression-free at last follow-up (median 16 months), including 13 patients who are progression-free more than two years after local therapy.

Conclusions:

OligoAR is a common and distinct pattern of acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade compared to sAR. OligoAR is associated with improved post-progression survival and some cases can be effectively managed with local therapies with durable benefit.

INTRODUCTION

PD-(L)1 blockade has opened the door to durable treatment that can approach cure in some patients with metastatic lung cancer. Unfortunately, this success is rare and most patients are initially or eventually become resistant. Acquired resistance (AR), defined as progressive disease after initial response to PD-(L)1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), occurs in ~50% of responders and warrants additional attention.1–3 The patterns of AR to PD-(L)1 blockade have not been routinely reported and are poorly understood, but could inform biologic underpinnings as well as treatment considerations. In particular, patients with progression limited to a few (three or less) isolated tumor lesions, here termed oligo-AR, could have unique disease characteristics warranting separate clinical consideration from widespread (over three isolated tumor lesions) systemic AR.2, 4

Prior reports suggest that locally-directed radiation, resection, or other local ablative therapies (i.e. radiofrequency) have potential efficacy in controlling limited metastatic disease.5–10 For example, in EGFR-mutant lung cancer, studies have demonstrated that radiation (XRT) or surgery following oligoAR to EGFR-directed tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can prolong tumor control with continued EGFR inhibition.11–13 Additionally, for de novo oligometastatic NSCLC, a randomized controlled trial of patients who received locally consolidative therapy with surgery or XRT after front-line systemic therapy had significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to maintenance therapy or observation.9 However, the settings of consolidative therapy and AR to moleculary targeted therapy are quite distinct from PD-(L)1 blockade where the role of local therapies in oligoAR to PD-(L)1 is not clearly defined.5–10, 14–20 Further, the strict definition of oligoAR requires additional investigation and initial criteria chosen here are based upon recent studies.4, 8, 21, 22

In contrast to the almost inevitable emergence of systemic AR to current molecularly targeted therapy strategies in lung cancer, PD-(L)1 can reinvigorate anti-tumor immunity even with only short-term exposure to therapy. We hypothesized that oligoAR to PD-(L)1 blockade may reflect local escape with otherwise ongoing anti-tumor immunity sustaining disease control elsewhere, and this setting could be particularly sensitive to local therapies as definitive treatment (i.e. in the absence of changing systemic therapy) to restore anti-tumor control. To investigate this hypothesis, we examined over 1,500 patients treated with PD-(L)1 blockade, characterizing the clinical features and outcomes of all patients who had AR to PD-(L)1 blockade, and devoting particular attention to outcomes among those with oligoAR treated with local therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

With Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board approval and in accordance with the Belmont report, we identified all patients with metastatic NSCLC who were treated with PD-(L)1-based immunotherapy from April 2011 through October 2018 (database lock of November 2019). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients treated with PD-(L)1 plus chemotherapy were excluded. PD-(L)1 + CTLA-4 blockade were allowed. Thoracic radiologists used Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 to assess response and progression on PD-(L)1 blockade. Patient characteristics were extracted from medical and pathology records. Pathologists determined PD-L1 expression scores as the percentage of tumor cells with partial or complete membranous staining primarily as previously described.4 Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed using MSK-IMPACT.23 Patients who died without imaging performed (n = 28) were excluded from this analysis as the classification of resistance (oligoAR vs. sAR) could not be definitively determined.

Patterns of resistance

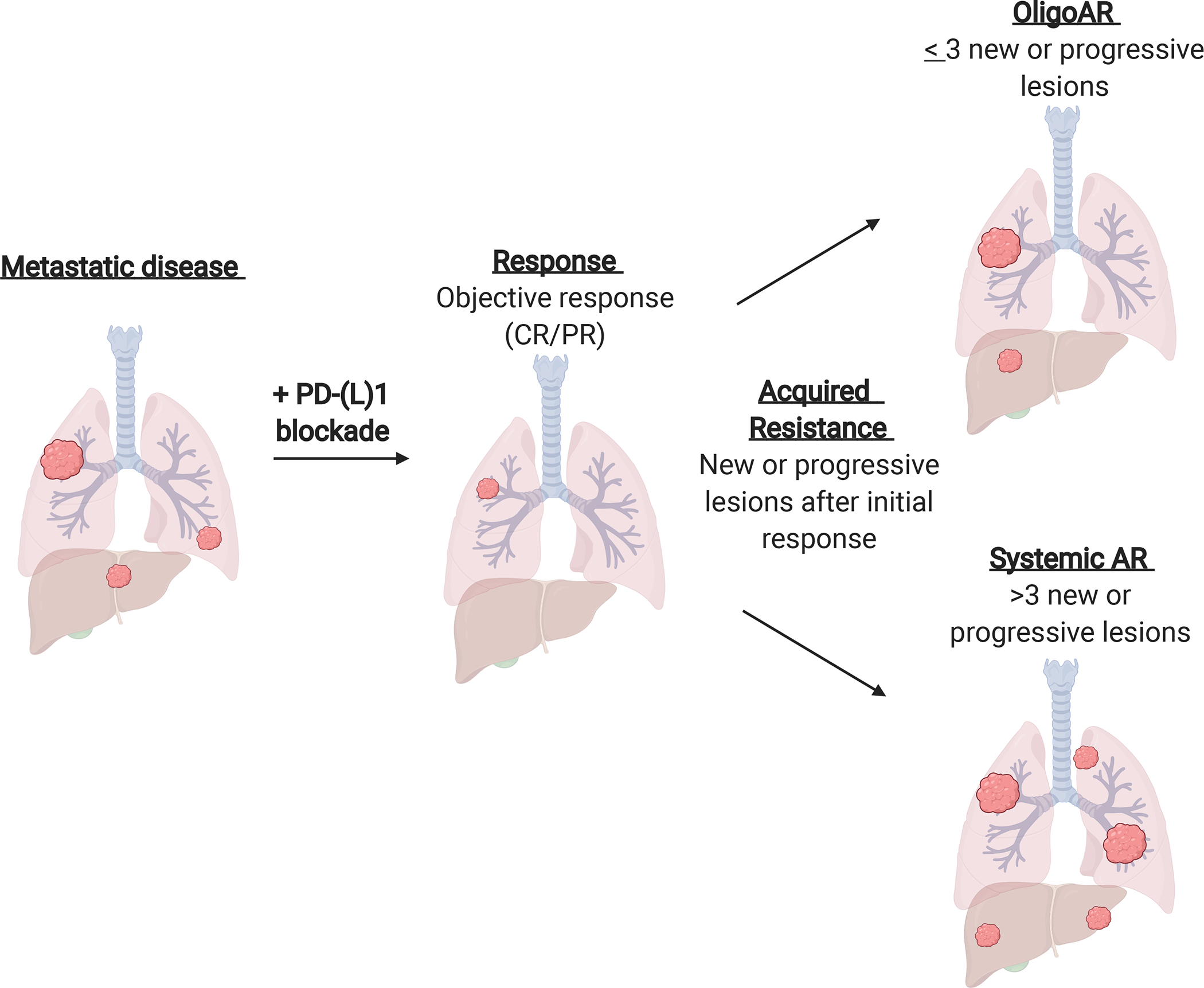

AR was defined as progressive disease or death after initial objective response (complete or partial response by RECIST 1.1) as previously described.24 AR was subdivided into two groups, oligo-AR and systemic AR, by the number of new and/or progressive lesions of disease (oligo-AR ≤ 3 lesions of disease progression) based upon prior studies (Figure 1).25, 26 This is consistent with prior randomized controlled trials utilizing radiation therapy for all metastatic lesions, where > 90% of patients enrolled had ≤ 3 lesions treated with stereotactic ablative radiotherapy.18

Figure 1. Schema for classification of systemic and oligo-acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade in lung cancer.

Acquired resistance (AR) is defined as progressive disease or death after initial objective response (complete or partial response (CR/PR) by RECIST 1.1). AR is subdivided into two groups, oligo-acquired resistance (oligoAR) and systemic AR, by the number of new and/or progressive lesions of disease progression (oligo-AR ≤ 3 lesions of disease progression, respectively).

Statistical Approach

The response to PD-(L)1 blockade was measured using PFS calculated from the date the patient began treatment to the date of clinical or radiologic progression or date of death. Patients who had not progressed at the time of database lock were censored at the date of last follow-up. Post-PD-(L)1 blockade OS was defined from date of progression on PD-(L)1 blockade to death or the end of follow-up. Patients who had not died were censored at date of last contact. We used the Fisher’s exact test or Pearson chi-square to compare proportions and the Mann-Whitney U test to assess between-group differences. PFS and OS were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methods. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software version 7 (La Jolla, CA, www.graphpad.com).

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

RESULTS:

Patient population

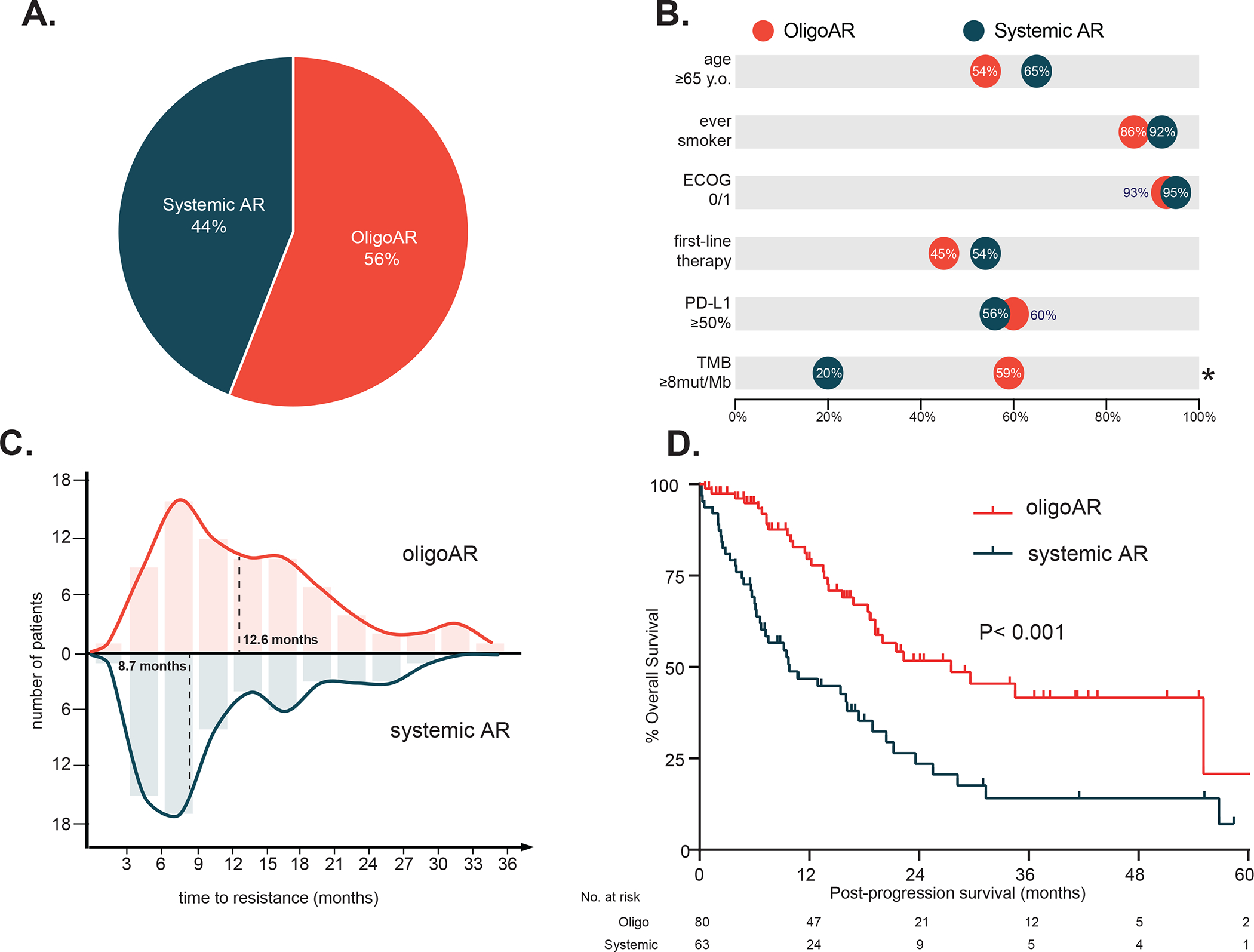

Among 1,536 patients who received PD-(L)1 blockade, 312 patients (20%) had an initial RECIST PR after PD-(L)1 treatment, and we identified 143 patients (46% of initial responders) who met the definition of AR and could be analyzed for patterns of resistance. Within this cohort of patients, eighty (56%) of the patients with AR met the parameters for oligoAR (Figure 2a), the majority of whom had only one isolated site of new or progressive disease (n = 49), which also aligned with prior studies.1, 9, 14, 25, 27

Figure 2. Clinical features of AR to PD-(L)1 blockade.

(A) Frequency of oligoAR and systemic AR. (B) Baseline characteristics of oligoAR and systemic AR prior to PD-(L)1 blockade. (C) Time to resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade in oligoAR vs systemic AR. (D) Overall survival post-progression on PD-(L)1 blockade in oligoAR vs systemic AR.

Clinical features of AR to PD-(L)1 blockade

Baseline characteristics prior to PD-(L)1 blockade

We hypothesized that oligoAR could signify a distinct AR phenotype, which might be identified retrospectively by analyzing baseline characteristics and features of initial response to PD-(L)1 blockade. With that in mind, we first compared the baseline clinical features of oligo-AR to that of all patients who developed systemic AR.

Baseline clinical characteristics such as age, sex, performance status, initial tumor burden, or smoking history among patients who developed oligo-AR were generally similar to patients who developed systemic AR (Table 1, Figure 2b). PD-L1 expression did not differ between oligo-AR and systemic AR (categorical in Table 1, median PD-L1 expression: oligo-AR 70%, systemic AR 50%, P = 0.35). However, the tumor mutational burden (TMB) for patients with oligo-AR was significantly higher than patients with systemic AR (Table 1, Figure 2b; median TMB; oligo-AR 9.8 mutations/megabase, systemic AR 5.3 mutations/megabase, P = 0.007).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with response to PD-(L)1 blockade by resistance type.

| OligoAR | Systemic AR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 80) | (N = 63) | ||

| Age (median, range) | 65 (45–87) | 67 (30–88) | 0.13 |

| Gender | |||

| Female - N, % | 35 (44) | 34 (54) | 0.24 |

| Male - N, % | 45 (56) | 29 (46) | |

| ECOG | 0.73 | ||

| 0 - N, % | 15 (19) | 14 (22) | |

| 1 - N, % | 59 (74) | 46 (73) | |

| 2 - N, % | 6 (8) | 3 (5) | |

| Baseline tumor burden (median, IQR)** | 57 (37–85) | 59 (35–99) | 0.46 |

| Line of therapy | 0.32 | ||

| Front-line - N, % | 36 (45) | 34 (54) | |

| Later-line - N, % | 44 (55) | 29 (46) | |

| Smoking pack years (median, IQR) | 30 (20–50) | 31 (13–50) | 0.85 |

| PD-L1 expression* | 0.67 | ||

| Negative - N, % | 11 (17) | 11 (24) | |

| Low (1–49) - N, % | 14 (22) | 9 (20) | |

| High (50+) - N, % | 38 (60) | 25 (56) | |

| TMB (median, IQR) | 9.8 (5–16) | 5.3 (4–8) | 0.007 |

PD-L1 expression is not available for all patients.

sum of the longest diameters in millimeters, by RECIST

On treatment features of response and resistance

We next investigated how the dynamics of response to PD-(L)1 blockade differed among oligo-AR and systemic AR. Best overall response percentage (BOR%) of oligo-AR was significantly greater than systemic AR (median BOR%: oligo-AR = −57%, systemic AR = −46%, P = 0.034). Further, oligo-AR developed resistance later than systemic AR (Figure 2C median PFS 12.6 vs. 8.7 mo, HR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.53–1.04, P = 0.036).

The spatial growth patterns of oligo-AR and systemic AR resistance also significantly differed (P = 0.003). Whereas regrowth at sites of disease persistence occurred at similar frequencies, oligo-AR had a higher frequency of de novo development of new lesions compared to systemic AR (Supplementary Table 1). The most common sites of progression in systemic AR and oligo-AR were the lung and lymph nodes (Supplementary Table 2). Like systemic AR, oligo-AR sites of progression were uncommon in the brain and liver (oligo-AR: brain = 6%, liver = 6%; systemic AR: brain = 3%, liver = 6%).

Post-progression outcomes by resistance subtype

Most notably, patient outcomes after the emergence of resistance diverged significantly between oligo-AR and systemic AR. Despite no significant differences in clinical characteristics (age, sex, performance status, initial tumor burden, smoking history, or the line of therapy for PD-(L)1 blockade), patients who developed oligo-AR had improved post-progression survival compared to patients with systemic AR (Figure 2D, median OS 28 vs 10 months, HR 0.40, 95% CI: 0.25–0.64, P < 0.001).

Further, when we compared post-progression survival by the number of new or progressive lesions, we also found no significant difference in survival among patients with 1–3 lesions of progression, but all had significantly improved post-progression survival compared to patients with 4 or more lesions of progression (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Figure 1). The striking differences in post-progression survival suggests that oligo-AR, in particular, might maintain partial anti-tumor immunity and warranted closer examination of management and outcomes among this patient population.

Post-progression management and outcomes among patients with oligoAR

Among patients with oligoAR, the majority had isolated progression at one lesion (1 lesion = 49 patients (61%), 2 lesions = 20 patients (25%), 3 lesions = 11 (14%)). We found no significant difference in post-progression survival among oligo-AR by number of lesions of progression (Supplementary Table 3).

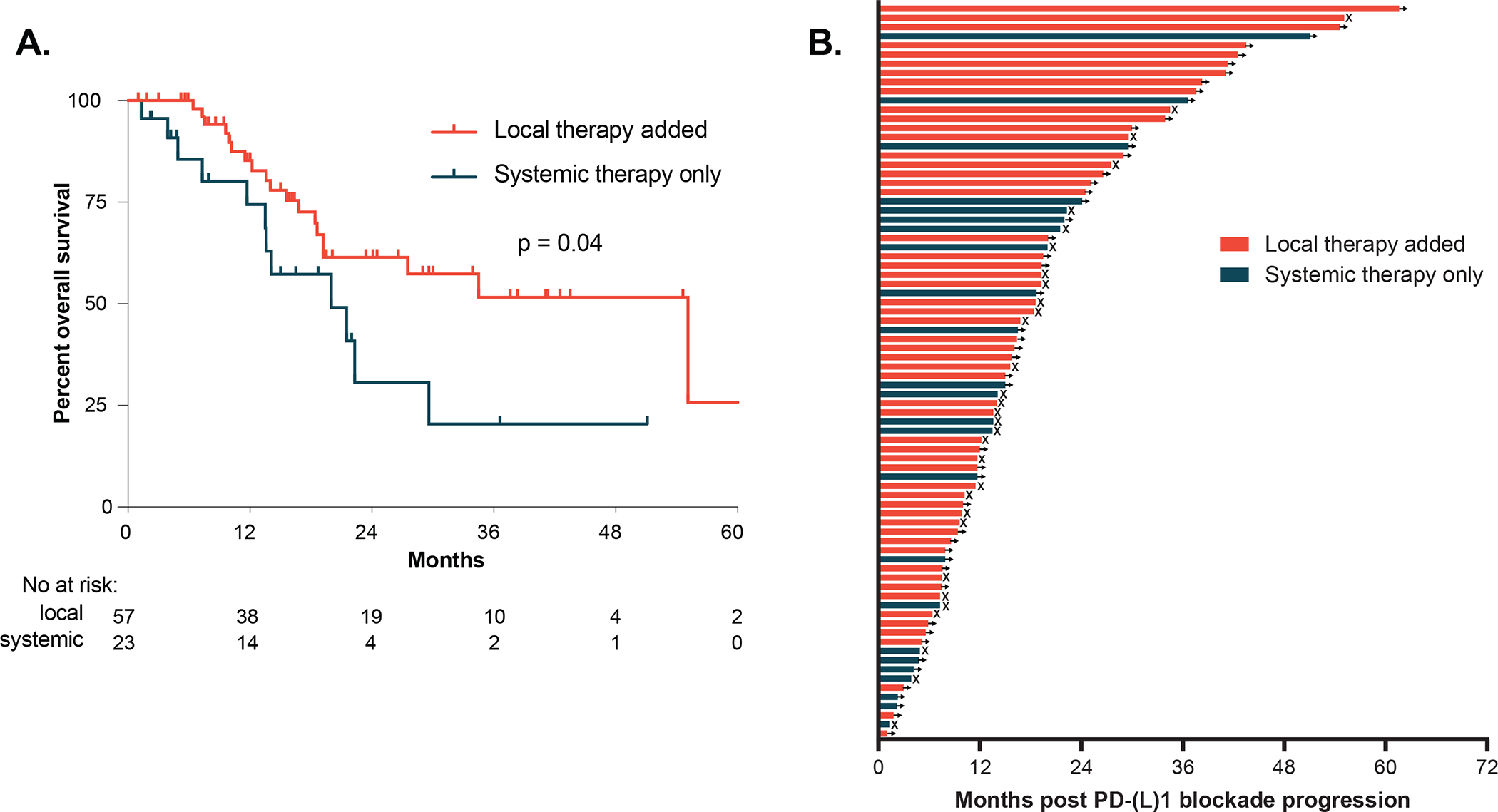

The addition of local ablative therapy for management of oligoAR

Patients with oligoAR commonly received multimodality therapy integrating local therapy; 47 (59%) patients received radiation, nine (11%) patients underwent surgical resection, and one patient (1%) was treated with radioembolization for oligoAR. The most common site of local therapy was the lung for radiotherapy and lymph node for surgical resection. Overall, patients whose treatment involved local therapy had significantly improved post-PD-(L)1 blockade progression OS compared to patients whose treatment did not involve local therapy(Figure 3A, HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.21–1.1, P = 0.04). We did not identify other significant differences in the characteristics of patients who received local therapy compared to those who did not, including PFS on PD-(L)1 blockade.

Figure 3. Management and outcomes of patients with oligoAR to PD-(L)1 blockade.

(A) Post-PD-(L)1 blockade progression overall survival with or without local therapy added. (B) Survival post-PD-(L)1 blockade progression by individual patients. Arrows denote ongoing survival and X indicate death.

Among patients who received local therapy for oligo-AR, the majority continued with PD-(L)1 blockade or on surveillance without a change in systemic therapy (n=56 of 57). Of these, 58% of patients continued PD-(L)1 blockade or surveillance at last follow-up (median 16 months post PD-(L)1 progression follow-up, 95% CI 12–20 months). Notably, 13 patients who received local therapy continued PD-(L)1 blockade or surveillance without further disease progression at least 2 years post progression (Figure 3B).

Rechallenge with PD-(L)1 blockade

Among patients with oligo-AR who did not receive local therapy, six patients who completed the initial course of PD-(L)1 blockade (N = 3) or discontinued due to toxicity (N = 3) were rechallenged with PD-(L)1 blockade. One of six patients (17%) had a partial response ongoing at last follow-up (>18 months) whereas the other five patients (83%) had progressive disease.

DISCUSSION

This report is among the first and largest to examine the clinical outcomes of patients with oligo-AR to PD-(L)1 blockade. We found that patients who ultimately develop oligo-AR have distinctive pre-treatment, on-treatment, and post-progression features relative to systemic AR. Further meriting separate clinical consideration from systemic AR, oligo-AR was associated with significantly improved outcomes after initial progression compared to systemic AR.

Our findings have important implications for management decisions with oligo-AR. Among patients with oligo-AR, we found local therapy was associated with improved OS, prolonged time on the current systemic therapy regimen at the time of progression, and led to durable disease control in a substantial number of patients. In oncogene-driven lung cancers treated with molecularly targeted therapy, local therapy has long been considered an effective tool for management of oligo-AR to TKIs 11, 13. Nevertheless, the benefits observed are often transient despite ongoing TKI therapy and oligo-AR can often be a precursor for the eventual emergence of more widespread systemic resistance requiring subsequent lines of systemic therapy. In contrast, we found that oligo-AR to PD-(L)1 does not inevitably presage forthcoming systemic progression. Instead, we found that local therapies could in many cases recapture the durable initial response offered by PD-(L)1 blockade response without the need for salvage cytotoxic therapy. These findings are important for clinicians to consider when faced with treatment decisions in the context of acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade. Ongoing prospective investigations (NCT03693014) will be critical to validate these findings and determine the population who would optimally benefit from multimodality treatment with local therapy and checkpoint blockade versus other systemic therapies.

The anatomic location and number of lesions of progression may also impact consideration of management strategies. In our experience, the majority of patients had isolated progression within the lung or lymph node and most patients were treated with radiation therapy, which corresponds with prior series.1, 3 With the caveat that routine CNS imaging was performed at the discretion of the treating provider, the brain was an uncommon site of resistance. Further understanding of how organ-specific sites of progression relates to outcomes and optimal treatment approaches are needed.

We hypothesize that the clinical pattern of localized resistance demonstrates the importance of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in mediating progression in this setting. Our prior work examining lesion-level patterns of response and resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade similarly concluded that even if response is systemic, resistance can be local.28 Tumor-intrinsic and TME-based mechanisms of resistance that have been previously described include loss or alteration of β2-microglobulin (B2M), which stabilizes MHC class I molecules at the cell surface and facilitates peptide loading, and alterations within the JAK/STAT pathway mediating tumor sensing of interferon could cause insensitivity to interferon-γ in the TME and resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade.2, 29–31 Additional exploration is required to assess the occurence of defects in antigen presentation or interferon-γ in relation to oligo-AR in particular. This is also the first study to compare TMB between oligoAR and systemic AR and the differences warrants further investigation of the neoantigen repertoire and clonality in different resistance states.

Further investigation can clarify what burden of disease is best classified as oligo-AR, how the number and types of metastatic sites influence outcomes, what characteristics best predict when locally directed therapy will produce durable benefit, and when surgery versus local ablative therapies versus radiation should optimally be used. Radiation was more commonly used for treatment of oligoAR in our cohort, though no clear treatment patterns were distinguished. An additional limitation of the analysis was that biopsies were not performed in all cases of disease progression to confirm resistance. In our analysis, ≤ 3 lesions of disease progression was chosen prior to analysis based upon recent studies,4, 8, 21, 22, but the optimal number of lesions and clinical implications of specific sites remains a subject of debate. Interestingly, our data also supported the 3-lesion threshold, as differences in clinical outcome were observed in patients with >3 lesions, but not within the 1–3 site threshold. Additional detailed investigation of outcomes with local therapy in >3 lesions/sites of progression is needed. Furthermore, it is notable that the bulk of prior studies have also focused on de novo oligometastatic and oligopersistance, but how this translates to oligo-AR is unclear and requires further investigation.5–10, 14 For now, we propose distinguishing oligo-AR as amenable to local therapies defined by a local multidisciplinary team - to be favored for local directed therapies or alternatively directed to dedicated clinical trials, as has been previously proposed by recent international consensus statements in the setting of oligometastasis.32

In summary, our report highlights that oligo-AR has characteristics and outcomes distinct from systemic AR, including significantly improved post PD-(L)1 blockade PFS and OS. Ongoing partial anti-tumor immunity could reflect differences in the underlying biology of oligo-AR compared to systemic AR and warrants further interrogation. Clinically, our findings support consideration of distinct clinical pathways for optimal management of oligo-AR versus systemic AR. Local therapy may be an important piece in this regard, and prospective evaluation of local therapy in the setting of oligo-AR will be critical. Building on the associations identified, translational studies are needed to determine the underlying mechanisms of oligo-AR and how to optimize treatment in the future.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance:

In this study, we examine the clinical patterns and the associated management of acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade in lung cancer. We identify that patients who develop acquired resistance (AR) limited to three or less isolated tumor lesions, here termed oligo-AR, have distinctive pre-treatment, on-treatment, and post-progression features relative to systemic AR, warranting separate clinical consideration. Importantly, among patients with oligo-AR, local therapy was associated with improved OS and durable disease control without the need for salvage cytotoxic therapy in a substantial proportion of patients. These findings are important for clinicians to consider when faced with treatment decisions in the context of acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade.

Acknowledgements:

Supported by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748) and the Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research at MSK. This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Kay Stafford Fund to MSK.

Footnotes

Disclosures: AJS reports consulting/advising role to J&J, KSQ therapeutics, BMS, Enara Bio, Perceptive Advisors, and Heat Biologics. Research funding: GSK (Inst), PACT pharma (Inst), Iovance Biotherapeutics (Inst), Achilles therapeutics (Inst), Merck (Inst), BMS (Inst), Harpoon Therapeutics (Inst). NS reports research support from Novartis. DM is a paid consultant to Shattuck Labs and Zygosity. JLS reports stock ownership in the following companies: Pfizer, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Inc., Merck & Co Inc and Chemed Corp. CJT Consultant and advisory board, Varian Medical Inc. CMR has consulted regarding oncology drug development with AbbVie, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Epizyme, Genentech/Roche, Ipsen, Jazz, Lilly, and Syros, and serves on the scientific advisory boards of Bridge Medicines, Earli, and Harpoon Therapeutics. MDH receives research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb; is paid consultant to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Janssen, Nektar, Syndax, Mirati, and Shattuck Labs; receives travel support/honoraria from AstraZeneca and BMS; and a patent has been filed by MSK related to the use of tumor mutation burden to predict response to immunotherapy (PCT/US2015/062208), which has received licensing fees from PGDx. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Gettinger SN, Wurtz A, Goldberg SB, et al. Clinical features and management of acquired resistance to PD-1 axis inhibitors in 26 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenfeld AJ, Hellmann MD. Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020;37:443–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heo JY, Yoo SH, Suh KJ, et al. Clinical pattern of failure after a durable response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci Rep 2021;11:2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Bandlamudi C, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of PD-L1 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinomas. Ann Oncol 2020;31:599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE, et al. Consolidative Radiotherapy for Limited Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e173501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence: a prospective, randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruers T, Van Coevorden F, Punt CJA, et al. Local treatment of unresectable colorectal liver metastases: results of a randomized phase II trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109:djx015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palma DA, Olson RA, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of Oligometastatic Tumors (SABR-COMET): Results of a Randomized Trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics 2018;102:S3–S4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, et al. Local consolidative therapy vs. maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non–small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of a multi-Institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1558–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Memon D, et al. Acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:9621–9621. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, et al. Local ablative therapy of oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non–small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:1807–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Yu H, Rusch VW, et al. Local therapy for oligoprogression in NSCLC patients being treated with osimertinib. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2019;104:235. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu HA, Sima CS, Huang J, et al. Local therapy with continued EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy as a treatment strategy in EGFR-mutant advanced lung cancers that have developed acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guckenberger M, Lievens Y, Bouma AB, et al. Characterisation and classification of oligometastatic disease: a European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendation. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:e18–e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai CJ, Yang JT, Guttmann DM, et al. Consolidative use of radiotherapy to block (CURB) oligoprogression: interim analysis of the first randomized study of stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with oligoprogressive metastatic cancers of the lung and breast. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2021;111:1325–1326. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chai R, Yin Y, Cai X, et al. Patterns of Failure in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Front Oncol 2021;11:724722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Li H, Fan Y. Progression Patterns, Treatment, and Prognosis Beyond Resistance of Responders to Immunotherapy in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front Oncol 2021;11:642883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gettinger S, Horn L, Jackman D, et al. Five-Year Follow-Up of Nivolumab in Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results From the CA209–003 Study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heo JY, Yoo SH, Suh KJ, et al. Clinical pattern of failure after a durable response to immune check inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci Rep 2021;11:2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rheinheimer S, Heussel CP, Mayer P, et al. Oligoprogressive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer under Treatment with PD-(L)1 Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalkidou A, Macmillan T, Grzeda MT, et al. Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy in patients with oligometastatic cancers: a prospective, registry-based, single-arm, observational, evaluation study. The Lancet Oncology 2021;22:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heo JY, Yoo SH, Suh KJ, et al. Clinical pattern of failure after a durable response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Scientific Reports 2021;11:2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn 2015;17:251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoenfeld AJ, Antonia SJ, Awad MM, et al. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to immunotherapy in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2021;32:1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalkidou A, Macmillan T, Grzeda MT, et al. Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy in patients with oligometastatic cancers: a prospective, registry-based, single-arm, observational, evaluation study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of Oligometastatic Cancers: Long-Term Results of the SABR-COMET Phase II Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:2830–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schanne DH, Heitmann J, Guckenberger M, et al. Evolution of treatment strategies for oligometastatic NSCLC patients – A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev 2019;80:101892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osorio JC, Arbour KC, Le DT, et al. Lesion-level response dynamics to programmed cell death protein (PD-1) blockade. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:3546–3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gettinger S, Choi J, Hastings K, et al. Impaired HLA class I antigen processing and presentation as a mechanism of acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov 20a17;7:1420–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sade-Feldman M, Jiao YJ, Chen JH, et al. Resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy through inactivation of antigen presentation. Nat Commun 2017;8:1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. aN Engl J Med 2016;375:819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lievens Y, Guckenberger M, Gomez D, et al. Defining oligometastatic disease from a radiation oncology perspective: An ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document. Radiother Oncol 2020;148:157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.