Abstract

Millennial caregivers, born between 1981 and 1996, are an understudied caregiver group. They experience stress-related consequences of caregiving and are unique in their developmental stage and generational norms. The purpose of this study was to understand the context of caregiving and stressors for these caregivers. Forty-two caregivers were recruited through Research Match and social media platforms. Caregivers completed online surveys with open-ended response questions and 15 caregivers completed semi-structured interviews. Data were analyzed deductively and inductively using the Stress Process Model as a framework. Millennial caregivers described uncertainty and disruption as overarching experiences. Stressors related to balancing caregiving, work, and family responsibilities were most prominent. Caregivers reported needing support from friends/family, health care team members, community, and work/governmental policy, and mental health treatment was reported as the most helpful approach for managing stress. Millennial caregivers have distinctive contexts that impact their caregiving needs, and caregiving interventions for this group must take these needs into consideration.

Keywords: millennial, family caregivers, development, stress, support needs

Millennial caregivers, individuals born between 1981 and 1996, are a diverse and understudied generational group of caregivers (Bialik & Fry, 2019; Weber-Raley, 2019; Vogels, 2019). Millennial caregivers constitute 25% of caregivers, and the proportion of Millennial caregivers is likely to increase exponentially as the aging population grows and individuals live longer with multiple chronic conditions (Flinn, 2018; NAC, 2020). Similar to other caregiving generations, Millennial caregivers experience physical, mental, and emotional stressors related to their caregiving responsibilities (NAC, 2020), and they have additional complexity related to their life stage with career and family (Bialik & Fry, 2019; Flinn, 2018). Large scale studies, including Caregiving in the U.S. and The Economic Consequences of Millennial Health from Blue Cross/Blue Shield, have addressed Millennial caregivers or Millennials as a group, but there is little published research focused on the intersection of caregiving with their developmental and generational trajectories (NAC, 2020; Moody’s Analytics, 2019).

Generational Characteristics, Development Stages, and Caregiving

Millennial caregivers have generational and developmental experiences that uniquely frame their caregiving experiences and potential stressors (Bialik & Fry, 2019; Flinn, 2018). As a growing group of caregivers, the consequences of stress they experience have important, long-lasting health and system implications for the care of individuals with chronic illnesses (Moody’s Analytics, 2019; NAC, 2020). Millennial caregivers often have stronger caring relationships with parents and other older adults that will carry through to caregiving relationships as these individuals age (Bialik & Fry, 2019; Fingerman, 2017; Howe & Strauss, 2000). The exponential growth of older adults with caregiving needs means that caregiving responsibilities for Millennials will only continue to grow (Flinn, 2018). The relationship between stress and health outcomes including poorer mental and physical health and increased risk of mortality for caregivers has been well-established, and is likely no different for Millennial caregivers (Bevans & Sternberg, 2012; NAC, 2020; Perkins et al., 2013). When compared to data from 2015, more Millennial caregivers report being in poor or fair health in 2020 (NAC, 2020). Millennials are experiencing poorer physical and mental health in young adulthood than previous generations (Moody’s Analytics, 2019).

As a generation, Millennial caregivers have unique social patterns that bring both strengths and vulnerabilities to their caregiving experiences. They are described as collaborative, empowered, networked, risk averse, and in search of meaning (Howe & Strauss, 2000). Millennial caregivers have been shaped by violence with mass shootings, 9/11, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. As digital natives, these caregivers adapted early to the internet going social, on-demand entertainment, and constant connectivity (Bialik & Fry, 2019). They have gone through the challenges of a global recession and now the pandemic (Greenwald Research, 2021), and their rates of home ownership and investment patterns are lower than previous generations (Bialik & Fry, 2019). As a caregiving cohort, there is a more even split between male and female caregivers, and as a generational group, women are working outside the home more than in previous generations (Flinn, 2018; Bialik & Fry, 2019).

Millennials have accumulated less wealth than Baby Boomers at the same age (Bialik & Fry, 2019). Millennial caregivers report high levels of financial strain and financial impact due to caregiving including unpaid or late bills, borrowing money from friends or family, and being unable to afford basic expenses (NAC, 2020). They are also least likely to report having health insurance compared to older caregiving generations (NAC, 2020). Millennial caregivers may also fall into the group of Sandwich Caregivers, or caregivers that are feeling compressed by their care responsibilities for both older adults and children (Weber-Raley, 2019). Millennial caregivers are the most diverse of any other caregiving group in terms of race or ethnicity and sexual and gender orientation, coinciding with the diversity in the generational cohort (Flinn, 2018; NAC, 2020). Family of choice, where individuals form close bonds with others outside of kinship relationships, may also contribute to greater caregiving responsibilities for Millennial caregivers (McCarthy & Edwards, 2011; NAC, 2020).

Caregiving research for individuals in early adulthood is limited. Some researchers have focused on emerging or “young adulthood” for caregivers between the ages of 18 and 25 (Greene et al., 2017), but many Millennial caregivers are older, while still within the boundaries of early adulthood (ages 18–40) (Lally & Valentine-French, 2021). The existing literature acknowledges the distinct needs of these caregivers with developmental milestones such as career building and establishing relationships and families (D’Amen, Socci, & Santini, 2021; McLaughlin et al., 2019). Millennial caregivers are vulnerable to mental health challenges including isolation and the struggle of balancing multiple life responsibilities (Moody’s Analytics, 2019). These challenges have been magnified by the pandemic (University of Pittsburgh, 2020). In addition to the literature gap addressing the experiences of Millennial caregivers, there are few caregiver interventions that have been tailored to Millennial caregivers and their life stage with work and family responsibilities (Ugalde et al., 2019). Before tailoring interventions to this group, it is important to understand the context of caregiving and sources of stress for this group.

Stress Process Model and Millennial Caregivers

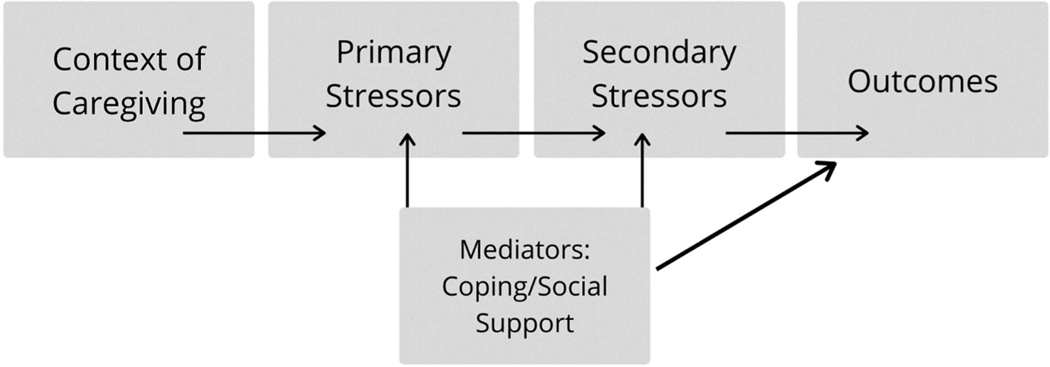

The Stress Process Model, outlined by Pearlin and colleagues (1990), provides a framework for understanding the Millennial caregiver stress response (See Figure 1). Pearlin et al. (1990) posit that the stress from caregiving is related to interrelated conditions including contextual factors (developmental and generational experiences for Millennials), primary stressors (stressors related directly to caregiving), and secondary stressors (strains outside of caregiving and internal caregiver strains). The outcomes of stress may be depression/anxiety, poor physical health, cognitive changes, or departure from caregiving. Mediators that may support better health outcomes include caregiver coping and social support (Pearlin et al., 1990).

Figure 1:

Stress Process Model

Study Purpose

Using the Stress Process Model as a guide, the purpose of this study was to understand the context of caregiving and stressors for Millennial caregivers and identify coping strategies currently employed by these caregivers.

Study Methods

Study Design

This study was one arm of a cross-sectional, qualitative descriptive study to examine the stress experiences of Millennial caregivers and to explore the needs and preferences of Millennial caregivers to inform the development of a stress and emotional regulation practice using an mHealth app. The mHealth portion of the study will be reported elsewhere. This study was exempted by a university-affiliated Institutional Review Board. Participants provided informed consent after reviewing the cover letter and agreeing to proceed with the study.

Participants

Study participants (N=42) were recruited using ResearchMatch, social media advertising (Facebook and Twitter), professional contacts, and national caregiving organizations. The goal of this study was to obtain a broad overview of Millennial caregiver needs (Sandelowski, 1995), therefore purposeful sampling was used to identify Millennial caregivers meeting the following inclusion criteria: born between 1981 and 1996; able to read, write, and speak English; provide care to an individual with a chronic illness for 10 or more hours per week, and access to the internet and a computer. Participants were excluded if they did not have access to a mobile phone.

Data Collection

Survey data were collected and managed using using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Utah (Harris et al., 2019). Surveys included demographic questions, and closed- and open-ended response questions about caregiving context and stress (Supplement A). Participants could indicate willingness to be contacted for one to two interviews. The mHealth arm included two interviews and is reported elsewhere. This arm included an in-depth semi-structured interview for data triangulation about Millennial caregiver stress experiences (Supplement B). One researcher conducted interviews with 15 participants using Zoom, and audio recordings from Zoom were transcribed verbatim. Participants were given a $15 gift card for completion of the survey and a $25 gift card for completion of the interview. A fraud protocol was instituted to identify fraudulent survey responses including time spent on the survey, responses that did not make sense, identical survey responses, and emails with nonsensical strings of numbers or letters (Teitcher, et al., 2015). If a survey met criteria for fraudulent or potentially fraudulent based on the protocol, the participant was contacted via email with instructions to contact the research team for resolution. Eleven surveys were identified as fraudulent and excluded from the total sample. Incomplete surveys (did not have open-ended responses) were also excluded (n=21). A total of 42 participants were included in the present analysis.

Data Analysis

Demographic data for participants (n=42) were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 to understand participant characteristics (SPSS, 2020). Open-ended response questions and semi-structured interviews were analyzed using qualitative thematic analysis by nine coders using Dedoose (Braun & Clark, 2006; Dedoose Version 9.0.35, 2018). The analysis began deductively with the open-ended responses using the Stress Process Model as an initial framework, with additional themes and sub-themes added inductively. These themes were then triangulated with the semi-structured interviews. Survey open-ended responses (n=42) and interviews (n=15) were double coded to establish coder agreement, and any differences were discussed during coding meetings. The first author led the coding process and arbitrated any coding disagreements. Notes were kept with each coding meeting, and all coders wrote memos to accompany any coding issues or insights that arose during the coding process. Exemplar quotes were identified for the table and results section. “Participant” denotes a quote from an open-ended survey response and “Interview” denotes a quote from a semi-structured interview. To preserve participant confidentiality, the survey responses were not connected to the interview data.

Trustworthiness was maintained through credibility (study protocol, reflexivity during coding meetings, and double coding data), dependability (use of codebook and audit trail), confirmability (data and research triangulation). Use of direct quotes from participants and use of thick description were also used to promote transferability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The target number of interviews for this arm of the study was 15 participants, so survey responses were collected until this target and targets for the mHealth arm were reached. Researchers anticipated at least 30 survey responses to reach interview targets. This analysis focused on cases rather than participants, and 15 interview cases and over 30 survey cases provided adequate data to reach thematic saturation (Sandelowski, 1995).

Results

Participants were primarily female (74%, n=31), White (83%, n=35), married, partnered or in a relationship (74%, n=32), and had attended some college or attained a college degree (83%, n=35). Just over half had an annual income of $50,000 or more (57%, n=24), about half were working full time (48%, n=20), and over half reported that caregiving had affected their employment (64%, n=27). Most participants resided with the care recipient (74%, n=31) and were a parent caring for a child (33%, n=14) or were caring for their own parent (29%, n=12) (See Table 1). Caregivers provided care for a range of conditions including Type I and Type II diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s and other dementias, stroke, epilepsy, autism and other developmental disorders, genetic disorders, anxiety, and depression. They spent an average of approximately 51 hours on caregiving (SD=50.32, range=10–168), and assisted the care recipient with an average of 10 tasks (SD=1.92, range=6–13).

Table 1:

Participant Demographics (N=42)

| Characteristic | Overall Sample n (%) | Interviewed (n=15) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 31 (74%) | 12 (80%) |

| Male | 8 (19%) | 2 (13%) |

| Non-Binary | 3 (7%) | 1 (7%) |

|

| ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 35 (83%) | 14 (93%) |

| Black | 8 (19%) | 3 (20%) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 5 (12%) | 3 (20%) |

| Asian | 2 (5%) | 1 (7%) |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Partnered/In | ||

| Relationship | 32 (74%) | 10 (67%) |

| Single | 8 (21%) | 3 (20%) |

| Divorced | 2 (5%) | 2 (13%) |

|

| ||

| Annual Income | ||

| ≥$50,000 | 24 (57%) | 5 (33%) |

| <$50,000 | 18 (43%) | 10 (67%) |

| Education | ||

|

| ||

| Less than HS | 1 (2%) | |

| HS or equivalent | 5 (12%) | 1 (7%) |

| Some | ||

| College/Associate’s, | ||

| Technical Certificate | 11 (26%) | 4 (27%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 15 (36%) | 7 (47%) |

| Graduate Degree | 9 (21%) | 3 (20%) |

|

| ||

| Employment | ||

| Full-Time | 20 (48%) | 9 (60%) |

| Part-Time | 9 (21%) | 3 (20%) |

| Not Employed, Family | 8 (19%) | 2 (13%) |

| Care | ||

| Not Employed, Looking | 2 (5%) | |

| Not Employed, Disabled | 1 (2%) | |

| Student | 1 (2%) | 1 (7%) |

|

| ||

| Employment Affected by | ||

| Caregiving | ||

| Yes | 27 (64%) | 12 (80%) |

| No | 15 (36%) | 3 (20%) |

|

| ||

| Relationship to Care | ||

| Recipient | ||

| Child | 14 (33%) | 5 (33%) |

| Parent | 12 (29%) | 5 (33%) |

|

| ||

| Spouse/Partner | 8 (19%) | 3 (20%) |

| Other | 8 (19%) | 2 (13%) |

|

| ||

| Reside with Care recipient | ||

| Yes | 31 (74%) | 10 (67%) |

| No | 11 (26%) | 5 (33%) |

|

| ||

| Hours/Week Caregiving | ||

| M (SD) | 50.5 (50.32) | 55.79 (60.95) |

| Range | 10–168 | 10–168 |

|

| ||

| Number Caregiving Tasks | ||

| M (SD) | 9.71 (1.92) | 9.93 (1.98) |

| Range | 6–13 | 6–13 |

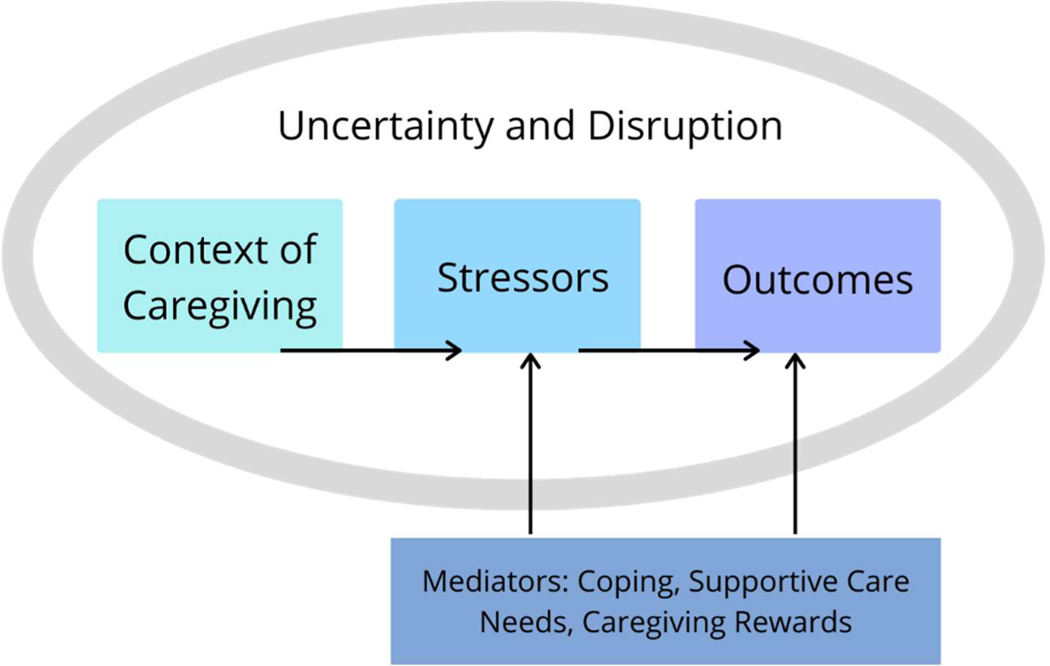

Figure 2 provides a conceptual overview of the study findings. Disruption and uncertainty were common threads throughout caregivers’ descriptions of their caregiving context and stressors. When caregivers discussed stressors, there was overlap between primary (caregiving) and secondary (non-caregiving) stressors. Caregivers described a push and pull among stressors, but described them as all being embedded in their day-to-day experiences. Therefore, the adapted model for Millennial caregivers encompasses both primary and secondary stressors into one category. In addition to caregivers’ coping and supportive care needs, many caregivers described the rewards of caregiving. This was included in the model as a mediator. Each theme with associated sub-themes will be described in greater detail below.

Figure 2:

Stress Process Model in Millennial Caregivers

Disruption and Uncertainty

Disruption and uncertainty were overarching factors described by caregivers that framed the caregiving context and caregiver stressors (See Figure 2 and Table 2). With disruption, caregivers described disruption in their achievement of developmental milestones such as building intimate relationships, having children, educational attainment, and career development: “I couldn’t handle a harder major without any support or without basically any resources (Interview 5);” and “It’s not like I can just go to dinner and come home whenever, go out with friends… because he has to get his IV antibiotics.” (Interview 14).” Another caregiver stated, “But it’s difficult to even start thinking about family planning because we have to think about some of the other endocrine issues that are there.” They also described disruption in their day-to-day functioning: “The few days after he has a seizure, I just like don’t sleep (Interview 1).”

Table 2:

Themes with Exemplar Quotes

| DISRUPTION | |||

|

Participant 40: “I have to work fewer hours in the office and more hours at home. I have also had to split my day up and work into the late-night hours. I have had to give up all traveling I was doing because I am taking care of my Mom every day.” Participant 44: “I never have any down time. My whole life is work or caregiving.” | |||

|

| |||

| UNCERTAINTY | |||

|

Interview 8: “I haven’t actually told my immediate boss that I am leaving, not because I don’t think she’d be supportive, but to be honest I was a little afraid that we would lose our health insurance early, and we have surgeries coming up, and that just made me really nervous.” Participant 47: “Taking care of them, the fact that they have NO plan for what comes next - what if something happens to one of them, if their landlord decides to sell, etc.” | |||

|

| |||

| Main Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Background and Context of Caregiving | Care Recipient Characteristics | Interview 12: “…my now eight-year-old son is a type 1 diabetic, and he got diagnosed when he was five, so we’re in our third year of dealing with it, and basically it’s a very high-maintenance disease. Nothing’s ever the same. One thing will be the same one day, and the next day it’ll be totally different.” | |

|

| |||

| Caregiver Characteristics | Interview 15: “I just noticed this from my lifetime of having immigrant parents… So I know that they answer my questions with a different kind of sense of relation to me than to my mom.” | ||

|

| |||

| Environment | Interview 9: “Okay, so for me specifically I think that caregiving can fall into a couple of different categories. As a woman, as a wife, as a mother I think that there’s a high societal pressure that is placed on us to take on the emotional wellbeing of other individuals in our lives and we’re expected to shoulder that.” | ||

|

| |||

| Stressors | Care Recipient Health | Interview 2: “I see the long-term side effects of uncontrolled Type 1 diabetes, and it scares me so much to look at him. He’s 27, and I’m like, ‘If you don’t get this under control now, this could be really bad for you in the future. I see these patients all the time, and their lives are not pretty, and it’s not a pretty life for you, it’s not a pretty life for me, and it’s not what I signed up for as your wife-- to be a full-time caregiver in that way, either.’ And so it is really difficult, but he doesn’t see it that way.” | |

|

| |||

| Balancing Caregiver Needs and Responsibilities with Caregiving | Interview 3: “I’m a manager. So I have to manage other people as well. It’s not like an easy job where I could just be like well, I could just do my work and then I’m done. It’s always constantly. And then caregiving is constantly. So it’s like having two full-time jobs at the same time.” | ||

|

| |||

| Relationship Dynamics | Interview 10: “… my whole life, she doesn’t communicate with me what’s going on with her medically. So, it’s just hard to tell sometimes. Like, I don’t always necessarily know what’s wrong, which … affects my ability to give care because like I have to just guess.” | ||

|

| |||

| Employment and Finances | Interview 9: “And then even later with my special needs child, I would have gainful employment here at times, but she would have a seizure and be hospitalized and I would be at the hospital with her for a week or two weeks or whatever constantly checking in with my supervisor and being told the whole time I’m in the hospital, ‘No, no, everything’s fine.’ And then when I come out of the hospital with her I don’t have a job, so I’m back at square one and attempting to reenter the workforce.” | ||

|

| |||

| Not Receiving Needed Support | Interview 12: “…at his school they don’t have a nurse there full-time, and so the office lady had given injections in the past, and he started there in kindergarten, and we didn’t feel comfortable with her doing it, and she was obviously nervous about doing it as well, so I’ve just been going to the school every day to give him his shots before lunch, and so that’s kind of hindered my work schedule.” | ||

|

| |||

| Caregiver Supportive Care Needs | Support from Health Care Team | Interview 8: “He’s not breathing, and I read the notes later, and the ER doctor said like ‘Mother was super-anxious about blah-blah-blah,’ and I was like ‘No. My child wasn’t breathing.’ So I guess it’s been a frustrating experience in a lot of ways, and we’ve been dismissed from specialists…” | |

|

| |||

| Support from Community | Interview 9: “ I’m involved in the community that I participate in. I participate in self help groups and grief support, things of that nature because I’m trying to take care of my own health, my own mental stability and my own growth, so that I can come back to and be that better mother that I know I’m capable of being.” | ||

|

| |||

| Support Socially | Interview 1: “Every single seizure, every single generalized seizure so far, I have called my mother, who is a doctor… and she just hangs out on the phone with me.” | ||

|

| |||

| Support with Work and Government Policy | Interview 1: “Yeah. I wish there was … someone who would advocate for me at work so that I knew I could keep my job and not face the consequences.” | ||

|

| |||

| Coping | Still figuring it out |

Interview 9: “And when life happened I experienced a mental health crisis… And then there was a lot of shame and a lot of judgment and a lot of blame in my personal failure to not be able to fulfill that role as the perfect mother any longer. I’m still struggling with those specific demons and coming to grips.” |

|

|

| |||

| Mental Health Treatment | Interview 10: “It’s the same therapist I’ve had since I was like 18. … they are very responsive and helpful, like managing stress and just making sure I know I’m not like crazy and my mom’s like-- her boundaries are different. So, like that person is helpful.” | ||

|

| |||

| Self-directed activities | Interview 3: “I think if there was something like an app. I hate to say this but like we always are on our phones. We always have our phones with us. So something I could use on the go… I need something I can consume in my time, something that’s easy to use in my life, something that’s five minutes or less.” | ||

| Workplace choice and flexibility | Participant 37: “I have to use creative time management skills to get all the work done, which often means working after dinner, or asking for help to complete work on time.” | ||

|

| |||

| Finding people who have the same experiences | Interview 2: “When we were first diagnosed I just had a friend of a friend reach out to me and say “You know, I have a diabetic too. If you have any questions let me know,” and that was just huge, because there’s some stuff that doctors don’t know or medical staff don’t touch on, and so she was a great sounding board for me.” | ||

|

| |||

| Rewarding Experiences (intrinsic): | Relationships—Closeness, Understanding | Participant 46: “I love her, she’s funny it’s bonding time for the whole family.” | |

|

| |||

| Growth—Care Recipient or Caregiver | Interview 9: “I have screwed up, I’m definitely not perfect and my redemption is in the process and trying to make sure that I get to a place where my children can see that I am healing and I am attempting to make right and that would make things significantly better for them and myself.” | ||

|

| |||

| Being There | Interview 3: “… the good parts are I get to spend time with her and see her.” | ||

|

| |||

| Not Rewarding | Participant 40: “I just keep going, there is nothing else to do.” | ||

Uncertainty was identified by caregivers in terms of not knowing what the future would look like for the care recipient or the caregiver. Caregivers noted, “I wake up ‘When is the other shoe going to drop?’ (Interview 7)’” and “there’s not a lot of bright and cheery outcomes for being a caretaker (Interview 5).” Caregivers also noted uncertainty about their employment and insurance “I haven’t actually told my immediate boss that I am leaving, not because I don’t think she’d be supportive, but to be honest I was a little afraid that we would lose our health insurance early (Interview 8)” and accessing external support, “I don’t know what is available to me (Interview 1).” Finally, caregivers described uncertainty about their adequacy as a caregiver, “Do I really know what I know” and “it’s very much like you’re like, ‘Am I really seeing this?’ (Interview 9).”

Caregiving Background and Context

Caregivers described the background and context of caregiving in three main areas: care recipient characteristics, caregiver characteristics, and the environment. Care recipient characteristics included illness and care needs, and the relationship between the caregiving and care recipient. One caregiver described: “My son will be four in April… and he has autism. My mother lives with me as well, and she has several different comorbidities (Interview 4).” Caregiver characteristics encompassed their gender, identity as a caregiver, and other areas of identity such as work status, health, or ethnicity/culture: “I was a disabled stay at home parent before (participant 38)” and “my family’s South American (interview 15).” Caregivers also described their responsibilities outside of caregiving, “I’m also a full-time student (Interview 13);” their own personal health and needs “I’m an agoraphobic (Interview 13);” and whether they had a choice to be a caregiver “I don’t wish this on anybody (Interview 1).” The social and physical environment that contributed to the caregiving context was described by caregivers. In particular, several noted the experience of marginalization as a caregiver due to other aspects of their identity: “I don’t know if it has anything to do with my mental health (Interview 13);” “Like I haven’t had sort of malicious like racist experiences… I just have to be aware of it (Interview 15);” “because of the color of our skin and where we live at they automatically assume I have Medicaid (Interview 4).”

Millennial Caregiver Stressors

Stressors described by Millennial caregivers focused on care recipient health, balancing caregiver needs and responsibilities with caregiving, relationship dynamics, employment and finances, and not receiving needed support. When discussing stressors related to care recipient health, Millennial caregivers noted challenges related to abrupt or sudden decline, the caregiving demands, and the uncertainty about the illness trajectory. “The hardest struggle… is just our inability to communicate. He’s considered non-verbal… it’s so hard to try to figure it out when you just want to make it better and you can’t.” Along with these care recipient health stressors, Millennial caregivers identified the difficulty of balancing their needs (health, social, financial, or mental/emotional well-being) and the needs of the care recipient. One caregiver noted: “The number of things I have to do. It is like having to take control of another person’s whole life and balance it with your own. It becomes overwhelming (Participant 40).” Caregivers described their many responsibilities outside of caregiving, and how the disruption due to caregiving responsibilities presented unique challenges: “I am having more trouble focusing than usual and I worry that my school work will decline in quality (Participant 38).”

Relationship dynamics were another source of stress for Millennial caregivers, with some reporting challenging relationships with the care recipient, family members, spouses or partners, and other social relationships. A caregiver described: “I have to split my time for my daughter and my mother which can cause tantrums and behavioral issues with my daughter (Participant 37).” Employment and financial well-being were pervasive issues for caregivers, with some describing difficulty covering expenses and managing employment while also being a caregiver. This participant stated, “I don’t have any PTO and if it wasn’t for FMLA I wouldn’t have my job (Participant 39).” Caregivers also noted stress related to not receiving the external support they needed to be a caregiver. This lack of support was discussed in the context of family, work, school and community, or the health care team: “So just not being able to have folks to help has been hard (Interview 15).”

Coping

Millennial caregivers identified coping strategies including mental health treatment, self-directed activities, finding others with shared experiences, and workplace choice and flexibility. Others stated that they were “still figuring [it] out,” with no concrete coping strategies established. Many caregivers described the use of mental health treatment including medication, therapy or counseling, and support groups. A caregiver described, “I have my own counselor that I see. I see her every other week (Interview 2).” For some, therapy was the most effective coping strategy for their stress, while other said “meds.” Caregivers also outlined self-directed activities such as TV/gaming, app use, music, reading, mindfulness, mindlessness, crying, exercise, routines, engaging socially, and mindset: “There’s journaling and meditation, coloring (Interview 9)”. Finding others with similar experiences was another coping strategy that Millennial caregivers found effective. One participant noted, “For me talking to people about similar situations is huge (Interview 12).” Finally, caregivers described making changes to their workplace situation, asking for flexibility, or seeking out employment that was more flexible to accommodate their caregiving role: “I know if I needed to change things, my boss is very understanding (Interview 10).”

Supportive Care Needs

Millennial caregivers described supportive care needs in four domains: support from the health care team, support from the community, support from family/friends, and support with national policy. When discussing supportive care needs related to the health care team, caregivers outlined the need for good communication, follow-through by health care team members, provision of respite services, and understanding and respect for the caregiver’s role as a central team member. In particular, caregivers wanted health care team members to recognize the caregiver’s expertise in knowing the care recipient’s needs. One caregiver noted, “but I have to talk to like ten doctors before I get one to listen to me (Interview 9).”

Caregivers also identified the need for community support with accessible resources, including financial support, an environment (both built and social), that promotes health, and an overall cultural shift to value the caregiving role. One participant described: “I had to spend a lot of weekends, like hours and hours, filling out financial aid applications for my mom… So, it’s like, why is it so hard? (Interview 15)” In addition to community support, caregivers identified the need for tangible support both emotionally and instrumentally from their friends and family—“co-workers are more understanding than my boss (Participant 39).” Caregivers outlined the need for friends and family to understand and acknowledge what caregiving requires. “There are days where I feel supported from my parents and my mother-in-law, but there are days where they cut me down, they cut her down (Interview 7).”

Along with support from family/friends, community, and the health care team, caregivers outlined the need for support in the workplace and at the governmental level with policy. Recommendations included universal health care, greater income support for caregivers, and improved workplace support for caregivers: “I wonder what it takes to have a cultural shift of caregiving being something that’s centered (Interview 15);” and “I wish there was … someone who would advocate for me at work so that I knew that I could keep my job and not face the consequences (Interview 1).”

Caregiving Rewards

In addition to caregiving stressors, caregivers identified the rewards that come from caregiving. Most of them were intrinsic and focused on relationships with greater closeness and understanding and growth for the care recipient and/or the caregiver. One caregiver noted that the reward of caregiving was “Feeling closer to my family and knowing there is trust (Participant 38);” and “in some ways it’s increased our bond (Interview 1).” Caregivers described the value of being there for the care recipient and being able to be involved in their care—“I would take all the responsibilities I have, all the pain, all the suffering, all the things I have just to see her better (Interview 7);” and “This is exactly where I would want to be (Interview 5).” Caregiver and care recipient growth was also noted: “I love learning to advocate for my daughter and for others with disabilities or medical complexities (Participant 20).” However, there were some caregivers that reported no rewards from their caregiving role—“Not rewarding. Just must be done. There’s no resentment. It exists outside of the axis of both. It is a duty (Participant 21).”

Discussion

In this study, we have described the Millennial caregiving experience using the Stress Process Model as a framework. We adapted the framework to encompass the Millennial caregiver experience, specifically highlighting the challenges of disruption and uncertainty for this caregiving group (See Figure 2). In addition to coping and supportive care needs, caregiving rewards were included as a potential mediator in the model. Caregivers described intrinsic rewards with caregiving such as personal growth, ability to be there for the care recipient, and greater closeness with the care recipient that may help with health outcomes related to the stress response.

Consistent with what is known about the Millennial generation and Millennial caregivers, these caregivers described diverse backgrounds and contexts that contributed to their experiences as caregivers including their care recipient characteristics and needs, their own life stage and needs, and the environment in which they were providing care (Flinn, 2018). As the most diverse generation, it was noteworthy that they described the experience of being marginalized for aspects of their identity such as gender, having low socioeconomic status, being a child of immigrant parents, or having a disability (Flinn, 2018). Family caregiving does not occur in a silo, and research and interventions that address Millennial caregivers should address intersectional experiences across gender identity, health, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and other dimensions of identity.

In addition to identity, the developmental stage of Millennials is of particular importance with caregiving, because there may be disruption in attainment of developmental milestones such as intimate partnerships, having children, buying a home, and building a career (Bialik & Fry, 2019). These milestones are already happening later for Millennials (Bialik & Fry, 2019), and the delay could be compounded by the demands of caregiving. This was exemplified by the through-lines of both disruption and uncertainty. Caregivers described disruption at work, their employment and financial progression, development of social relationships, and personal development. Caregivers also noted uncertainty about the future and how caregiving would impact them in these same areas.

The stressors outlined by Millennial caregivers are consistent with research findings focused on other caregiving populations. Stressors related to care recipient health are to be expected, and most caregivers are juggling responsibilities along with their caregiving role (NAC, 2020). Our findings are unique to the Millennial generation with their developmental stage—the balancing act these caregivers are navigating to maintain employment, build social and family relationships, continue their education, and ensure their own health does not deteriorate (Flinn, 2018). These caregivers are in the developmental prime of their life, and the consequences of stress on their health and ongoing social development are essential factors to acknowledge (Lally & Valentine-French, 2021). While not all of the stressors identified by caregivers would be classified as negative stress, any stressor initiates the stress response in the body with associated health consequences (Bienertova et al., 2020).

Employment and financial challenges were a consistent source of stress for caregivers, and almost half of the caregivers in this study were employed full time. The research on caregiver employment suggests that greater work demands are associated with poorer quality of life (Yu-Nu et al., 2020). Caregivers described coping mechanisms with choice of employment or career, or the choice not to focus on career, because of their caregiving responsibilities. They also outlined the need for greater financial and workplace support for caregivers. The Biden administration has released funds for caregiver support through the National Family Caregiver Support Program, but this focuses on caregivers of older adults (The White House, 2021). Additionally, the American Families Plan includes provisions for expanded paid family and medical leave and access to child care for families (The White House, 2021). Millennial caregivers may be providing care for children or both adults and children with chronic illnesses, so services and support need to be provided at both ends of the lifespan for caregivers (Weber-Raly, 2019).

Other coping strategies described by Millennial caregivers were self-directed activities such as app use, exercise, crying, mindlessness, and mindfulness, among others. Some caregivers identified mental health treatment as the most helpful strategy. Caregivers described the value in medication, counseling, and support groups to help with coping. Millennials as a generation are experiencing a health shock—unpredictable illnesses that diminish health—related to mental health decline on par with the effects of AIDS on Baby Boomers (Moody’s Analytics, 2019). Reasons for this are not fully understood, but could be related to increased isolation and decreased economic security (Moody’s Analytics, 2019). Clinicians and researchers should include mental health as a contextual factor when supporting this group of caregivers (Moody’s Analytics, 2019). As a generation of digital natives who are also busy and highly stressed, accessible mental health treatment and interventions should be a priority for Millennial caregivers (Bialik & Fry, 2019). In addition to traditional modalities for mental health support, there is growing research to support the use of telehealth (Warren & Smalley, 2020), particularly with the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-directed mental health treatment through mHealth apps is also growing, although the evidence is less robust (Marshall, Dunstan, & Bartik, 2020).

Millennial caregivers identified the need for greater support across social domains—family/friends, community, health care team, and nation. Some caregivers described the challenge of being a caregiver during a life stage where their role is often unacknowledged or dismissed in social, work, or health care environments. Millennial caregivers described the need to be seen as the expert in the care of the care recipient and be included as a member of the health care team. Broadly, caregiving is being embraced more in the national consciousness as a public health issue, but is often ignored in younger caregivers, such as Millennials (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018; Flinn, 2018). This can be problematic when caregivers interact with the health care team. Caregivers provide the bulk of care tasks at home for individuals with chronic conditions, and their input about what is possible with resources, time, and skills is of utmost importance to the safety and well-being of care recipients (NAC, 2020). Interventions focused on communication between the healthcare team and Millennial caregivers, assessment of caregiver resources and needs, referrals, and social support for both the care recipient and caregiver may be a way to better integrate Millennial caregivers into the care team (Becque et al., 2019; Parmar et al., 2019; Schulz et al., 2018).

Limitations

While not central to this analysis, this study was conducted in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, and caregivers noted the effects of the pandemic on their caregiving situation. Prior research suggests that COVID-19 has intensified the family caregiving experience (Pitt, 2020), and therefore the results should be interpreted with this in mind.

Conclusion

Our study fills a research gap in understanding the stressors and supportive care needs of Millennial caregivers. Using the Stress Process Model, we identified unique developmental and generational factors affecting the Millennial caregiving experience including employment, life stage with family building, and attainment of financial security. Caregivers also described coping strategies, rewards, and supportive care needs that can provide a source for intervention in the health care system and with further research investigation. Providing adequate support and enhancing coping for this caregiver group may help maximize caregiving rewards while minimizing adverse health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Drs. Thomas Hebdon, Wilson, Aaron and Ms. Neller and Kent-Marvick are supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR013456). This study was funded by the One-U For Caregiving Initiative at the University of Utah.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Becqué YN, Rietjens JAC, van Driel AG, van der Heide A, & Witkamp E. (2019). Nursing interventions to support family caregivers in end-of-life care at home: A systematic narrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 97; 28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevans M, & Sternberg EM (2012). Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA, 307(4), 398–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialik K, & Fry R. (2019). Millennial life: How young adulthood today compares with prior generations. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/02/14/millennial-life-how-young-adulthood-today-compares-withprior-generations-2/

- Bienertova-Vasku J, Lenart P, Scheringer M. (2020). Eustress and distress: Neither good nor bad, but rather the same?. BioEssays, 42. 10.1002/bies.201900238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3; 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2018). Caregiving for family and friends—A public health issue. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/aging/agingdata/docs/caregiver-brief-508.pdf

- D’Amen B, Socci M. & Santini S. (2021). Intergenerational caring: A systematic literature review on young and young adult caregivers of older people. BMC Geriatrics, 21(105). 10.1186/s12877-020-01976-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose Version 8.0.35. (2018). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL (2017). Millennials and their parents: Implications of the new young adulthood for midlife adults. Innovation in Aging, 1(3). 10.1093/geroni/igx026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinn B. (2018). Millennials: The emerging generation of family caregivers. AARP, Washington D. C. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2018/05/millennial-family-caregivers.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Cohen D, Siskowski C, & Toyinbo P. (2017). The relationship between family caregiving and the mental health of emerging young adult caregivers. Journal of Behavioral Health Servives Research, 44(4), 551–563. 10.1007/s11414-016-9526-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald Research. (2021). Financial perspectives on aging and retirement across the generations. Society of Actuaries. Retrieved from https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/files/resources/research-report/2021/generations-survey.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, … REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe N, & Strauss W. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27). Armonk, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Lally M, & Valentine-French S. (2020). Emerging and early adulthood. Iowa State University Digital Press. Retrieved from https://iastate.pressbooks.pub/parentingfamilydiversity/chapter/early-adulthood/ [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM, Dunstan DA, Bartik W. (2020). Apps with maps—Anxiety and depression mobile apps with evidence-based frameworks: Systematic search of major app stores. JMIR Mental Health 7(6); e16525. doi: 10.2196/16525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JR, & Edwards R. (2011). Families of choice. In Key concepts in family studies (pp. 57–58). SAGE Publications Ltd, 10.4135/9781446250990.n13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JK, Greenfield JC, Hasche L, & De Fries C. (2019). Young adult caregiver strain and benefits. Social Work Research, 43(4); 269–278, 10.1093/swr/svz019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moody’s Analytics. (2019). The economic consequences of millennial health. Blue Cross Blue Shield. Retrieved from https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/file-attachments/health-of-america-report/HOA-Moodys-Millennial-11-7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. (2020). Caregiving in the U.S. National Alliance for Caregiving. Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar J, Anderson S, Abbasi M, Ahmadinejad S, Bremault-Philips S, … Tian PGJ (2020) Support for family caregivers: A scoping review of family physician’s perspectives on their role in supporting family caregivers. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28, 716–733. 10.1111/hsc.12928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5); 583–594. 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M, Howard VJ, Wadley VG, Crowe M, Safford MM, Haley WE, … Roth DL. (2013). Caregiving strain and all-cause mortality: Evidence from the REGARDS study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychologic Sciences & Social Sciences, 68(4), doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR, Friedman EM, Martsolf GR, Rodakowski J, & James AE (2018). Changing structures and processes to support family caregivers of seriously ill patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 21(S2), 36–42. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitcher JE, Bockting WO, Bauermeister JA, Hoefer CJ, Miner MH, & Klitzman RL (2015). Detecting, preventing, and responding to “fraudsters” in internet research: ethics and tradeoffs. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(1); 116–133. 10.1111/jlme.12200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugalde A, Gaskin CJ, Rankin NM, Schofield P, Boltong A, Aranda S, … Livingston PM (2019). A systematic review of cancer caregiver interventions: Appraising the potential for implementation of evidence into practice. Psychooncology, 28(4), 687–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Pittsburgh. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on family caregivers: A community survey from the University of Pittsburgh. National Rehabilitation Research & Training Center on Family Support at the University of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Full_Report_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wang YN Hsu WC, Shyu YIL (2020). Job demands and the effects on quality of life of employed family caregivers of older adults with dementia: A cross-sectional study, Journal of Nursing Research, 28(4); e99. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JC & Smalley KB (2020). Using telehealth to meet mental health needs during the COVID-19 crisis. The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/using-telehealth-meet-mental-health-needs-during-covid-19-crisis [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Raley L. (2019). Burning the candle at both ends: Sandwich generation caregiving in the U.S Retrieved from https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/NAC-CAG_SandwichCaregiving_Report_Digital-Nov-26-2019.pdf

- The White House. (2021). Fact sheet: The American Families Plan. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/28/fact-sheet-the-american-families-plan/

- The White House. (2021). Fact sheet: Biden-Harris administration delivers funds to support the health of older Americans. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/05/03/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-delivers-funds-to-support-the-health-of-older-americans/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.